ISSN: 2685-9572 Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro

Vol. 8, No. 1, February 2026, pp. 85-96

Grid-Calibrated Patch Learning for Braille Multi-Character Recognition

Made Ayu Dusea Widyadara 1, Anik Nur Handayani 2, Heru Wahyu Herwanto 3, Tony Yu 4,

Marga Asta Jaya Mulya 5

1,2,3 Department of Electrical Engineering and Informatics, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Negeri Malang, Malang, East Java, Indonesia

4 Electrical and computer engineering, Rice University, Houston, Texas, United States

5 Energy and Manufactur Research Organisation, Badan Riset Dan Inovasi Nasional (BRIN), Tangerang, Indonesia

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 04 November 2025 Revised 27 December 2025 Accepted 15 January 2026 |

|

The approach presents a multi braille character (MBC) recognition system for Indonesian syllablesdesigned to address real-world imaging variations. The proposed framework formulates 105-class visual classification task, where each class represents a two-character Braille unit. This design aims to preserve inter-character spatial relationships and reduce error propagation commonly found in single-character segmentation approaches. A carefully constructed dataset undergoes spatial pre-processing stages, including rotation normalization, grid assignment, and multicell cropping, resulting in uniform 89×89 pixel image patches that ensure geometric consistency across samples. To enhance model generalization under varying illumination conditions, single-dimension photometric augmentation is applied exclusively during training, including brightness (±25%), exposure (±20%), saturation (±40%), and hue (±30%). ResNet-101 is adopted as the backbone architecture based on prior comparative studies conducted on the same dataset, demonstrating its effectiveness in capturing fine-grained Braille dot shadow patterns. The network is trained for 300 epochs with a batch size of 32 under consistent experimental settings, and performance is evaluated using a confusion-matrix-based framework with overall accuracy as the primary metric. Experimental results indicate that moderate photometric reductions significantly improve recognition performance by preserving critical micro-contrast cues. In particular, an exposure reduction of −20% achieves the best balance between accuracy (86.13%) and training efficiency (14.12 minutes), outperforming the non-augmented baseline (74.37%, 22.10 minutes). A hue reduction of −30% further improves robustness to ambient color variations, while aggressive positive adjustments degrade performance due to structural distortion. These findings confirm the effectiveness of the proposed MBC framework for practical Braille recognition in real-world environments. |

Keywords: Braille Recognition; Deep Learning; Multi-Braille Character (MBC); Grid Alignment; ResNet-101 |

Corresponding Author: Anik Nur Handayani, Department of Electrical Engineering and Informatics, Faculty of Engineering,Universitas Negeri Malang, Malang, East Java, Indonesia. Email: anik.nur.ft@um.ac.id |

This work is open access under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: M. A. D. Widyadara, A. N. Handayani, H. W. Herwanto, T. Yu, and M. A. J. Mulya “Grid-Calibrated Patch Learning for Braille Multi-Character Recognition” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 85-96, 2026, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v8i1.15199. |

- INTRODUCTION

A computer vision-based Braille recognition system with deep learning offers a promising solution due to its ability to automatically and robustly extract raised dot patterns under various lighting conditions and paper textures [1]-[3]. The Multi Braille Character (MBC) based approach is strategic for syllabic Indonesian, as it has the potential to reduce serial error propagation while speeding up reading time. This approach is inspired by multi-character recognition and syllable segmentation studies in other domains [4][5]. A variety of approaches have been developed to facilitate the recognition of Braille from scanned or captured images. These approaches include the use of image processing techniques and artificial intelligence [6]-[8]. The primary challenges associated with Braille detection include the variability of dot shapes, the presence of noise in the background, and irregularities in lighting that occur during the capture of images [9]-[11].

The present study focuses on Multi Braille Character (MBC) recognition, which consists of 105 classes based on the combination of two braille characters per image, ranging from "ba" to "zo." To ensure the model's capacity for generalization to real environmental variations is maximized, an image augmentation technique is employed. This technique encompasses modifications in brightness (±25%), exposure (±20%), saturation (±40%), and hue (±30°), a methodology that has been previously demonstrated to be effective in related studies [12]-[15]. It is hypothesized that moderate photometric augmentation improves MBC recognition robustness by preserving essential dot shadow contrast under realistic imaging conditions. ResNet-101 is selected as the backbone network due to its deep residual structure and its stable performance reported in prior Braille recognition studies, as well as in the authors’ previous experiments conducted on the same dataset [16][17].

Research on braille detection has been carried out using various approaches, including morphological segmentation [18][19], support vector machine (SVM) based recognition [20]-[22] as well as the use of convolutional neural networks (CNNs), such as LeNet and AlexNet [23][24]. However, there is a need for further research on the detection of Multi Braille Character (MBC) with intensive augmentation schemes and empirically adjusted image resolutions, such as the use of 89x89 pixel resolution inspired by the Fibonacci sequence, which has been adopted in prior studies as a heuristic for balancing spatial detail preservation and computational efficiency. In the context of Braille recognition, this resolution was found to retain critical dot–shadow micro-structures while minimizing redundant background information [25]-[27]. Existing studies predominantly focus on single-character Braille recognition or employ generic image resolutions, with limited investigation into multi-Braille-character (MBC) recognition under controlled photometric augmentation and calibrated spatial resolutions. In particular, the combined impact of resolution selection, dot–shadow geometry preservation, and single-dimension photometric perturbation remains insufficiently explored.

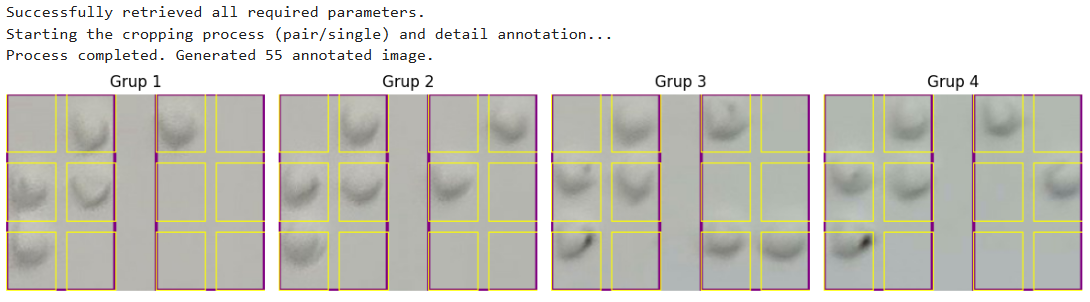

The purpose of this research is to develop a Multi Braille Character (MBC) detection model based on the ResNet101 architecture and evaluate its performance on an augmented MBC dataset comprising 105 classes. The core contribution of this research lies in the evaluates a Fibonacci inspired resolution calibration scheme and various augmentations for Multi-Braille Character recognition can be seen in Figure 1.

|

(a) | (b) | (c) |

Figure 1. The following braille characters are presented: the dot matrix (a), the letter ‘b’ single character (b), Multi-Braille Character (MBC) unit “ba”, which constitutes the core recognition target in this study (c) [16]

- LITERATURE REVIEW

Research in the domain of image-based Braille recognition has demonstrated substantial advancement, concomitant with the evolution of convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures and data augmentation techniques. A plethora of approaches have been proposed to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of detecting Braille characters, particularly in the context of complex datasets comprising multi-character or multi-class characters. The following literature studies pertain to the subject of braille detection (Table 1):

Table 1. Literature Review of Deep Learning Architecture in Braille Character Classification and Detection

Ref | Method / Focus | Result |

[1] | End-to-end CNN for Braille OCR | 95.2% (English) and 98.3% (DSBI) accuracy |

[28] | CNN + Ratio Character Segmentation (RCSA) | 98.73% accuracy on 71 Braille classes |

[29] | Custom CNN for Braille detection & TTS | 96.15% accuracy |

[21] | Grade-1 Braille pattern identification | ≥97% on most docs; 100% on three |

[30] | ResNet-based Braille classification | Up to 100% on test subsets |

[31] | Anchor-free Braille detection in natural scenes | Good small-object detection (mAP not reported) |

[32] | DL for low-light enhancement survey | Motivates robustness to exposure/brightness variation |

[33] | LLE evaluation | Provides exposure/contrast pre-processing guidelines |

[34] | Augmentation survey (brightness/hue/saturation) | Recommends safe ranges to avoid dot-pattern distortion |

[35] | Retinex for low-light enhancement | Improves contrast and SNR; complements exposure aug. |

[36] | Braille detection in varied lighting | Supports need for photometric augmentation |

- METHODS

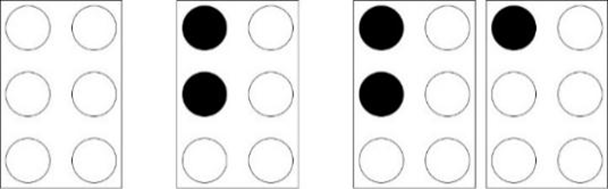

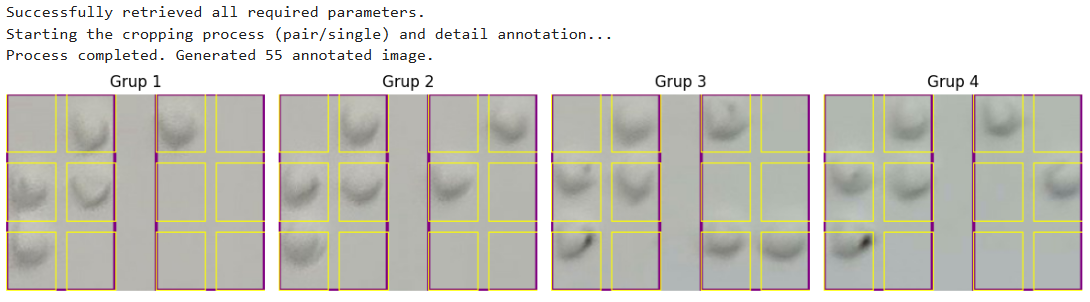

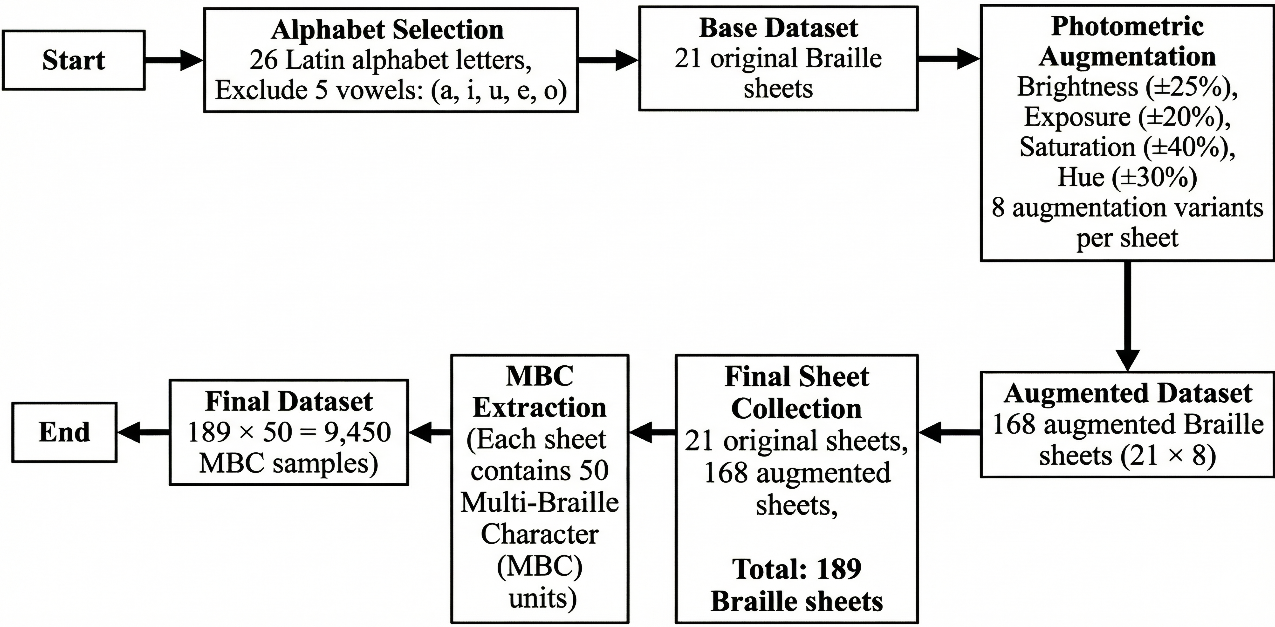

The proposed method is divided into six primary operational stages: data collection, dataset partitioning, pre-processing and MBC splitting, augmentation (training only), model training, and evaluation. The process begins with 1,050 original images representing 105 MBC (Multi Braille Character) classes. The data is then stratified by a strict ratio into training, validation, and testing sets. In the pre-processing stage, an interactive rotation-grid normalization is applied, followed by a multi-cell cropping (MBC splitting) procedure that produces homogeneous input patches of 89 x 89 pixels. To improve generalization, photometric augmentation (brightness +- 25%, exposure +- 20%, saturation +- 40%, and hue +- 30%) was applied exclusively to the training data (train-only) to strictly prevent data leakage to the validation and testing sets. The ResNet-101 architecture model was then trained for 300 epochs with a batch size of 32, and performance was evaluated using industry-standard metrics: Test Accuracy, Macro-F1 Score, and computation time. The complete, replicable experimental workflow is presented in Figure 2.

Ensuring data pre-processing is meticulous and consistent is imperative for the successful training of deep learning models [37], especially in fine-grained classification tasks such as Multi Braille Character (MBC) recognition that are highly sensitive to spatial orientation and the visual quality of dots. In order to ensure the reproducibility and verifiability of our process, we have summarized the transformative steps from raw Braille image to homogeneous input patch in the form of PSEUDOCODE.

PSEUDOCODE: Multi-Braille Character (MBC) Recognition------------------------------------------------------------------------------ # Constants PATCH_SIZE = 89 NUM_CLASSES = 105

1) Data Collection images, sheet_labels = load_braille_sheets(path) # 21 Braille sheets

2) Rotation Normalization for img, sheet_label in zip(images, sheet_labels): angle = estimate_rotation(img) # manual or automatic img_norm = rotate(img, angle) 3) Grid Assignment grid_params = set_grid(img_norm) # anchor(x0,y0), cell_w, cell_h, # spacing_x, spacing_y, rows, cols

4) Patch Extraction for (i, j) in grid_cells(rows, cols): x1, y1, x2, y2 = compute_cell_bounds(grid_params, i, j) patch = img_norm[y1:y2, x1:x2] patch = resize(patch, PATCH_SIZE, PATCH_SIZE) label = assign_mbc_label(sheet_label, i, j) dataset.append(patch, label)

5) Dataset Split train_set, val_set, test_set = split_dataset( dataset, train_ratio = 0.70, val_ratio = 0.20, test_ratio = 0.10, stratified = True )

6) Model Training model = initialize_model(backbone="ResNet-101", num_classes=NUM_CLASSES) train_model( model, train_set, val_set, augmentation = {brightness, exposure, hue, saturation} )

7) Evaluation y_true, y_pred = evaluate(model, test_set) compute_metrics(y_true, y_pred, metrics=["accuracy", "precision", "recall", "f1-score"]) save_model(model) save_confusion_matrix(y_true, y_pred)

|

Figure 2. Flowchart of Multi Braille Character (MBC) recognition method

- Collect Data

The dataset is taken from Braille sheets organized by syllable format, given the focus of this study on fine-grained Multi Braille Character (MBC) classification. Where each MBC represents a multi-character combination. To ensure consistency and integrity of the visual input which is a key factor for robustness of the model a strict acquisition protocol was implemented. Image acquisition was performed indoors with a lighting system consisting of three 10watt LED lights positioned at a 45° angle relative to the Braille sheet [20]. These controlled lighting arrangements are strategically designed to accentuate dot protrusions through the formation of subtle shadows, thereby enhancing contrast and effective feature extraction. The formation of these shadows serves as the foundational principle in the domain of computer vision-based Braille dot detection. The CNN model operates on the premise that shadow patterns of protrusions are more reliable indicators than tactile data [38].

- Augmentation

Perform augmentation process from the original dataset of 105 classes with 4 types of augmentation, namely brightness (±25%), exposure (±20%), saturation (±40%), and hue (±30%), a methodology that has been previously demonstrated to be effective in related studies [12]. These variations collectively expand the dataset from the original 1,050 images to 9,450 samples, which strengthens the model's robustness to varying lighting conditions. By simulating a wide range of non-ideal image capture conditions, this multidimensional augmentation serves as a vital regulation technique, ensuring ResNet-101 can learn a robust feature representation and maintain optimal performance.

- Data Rotation and Transformation

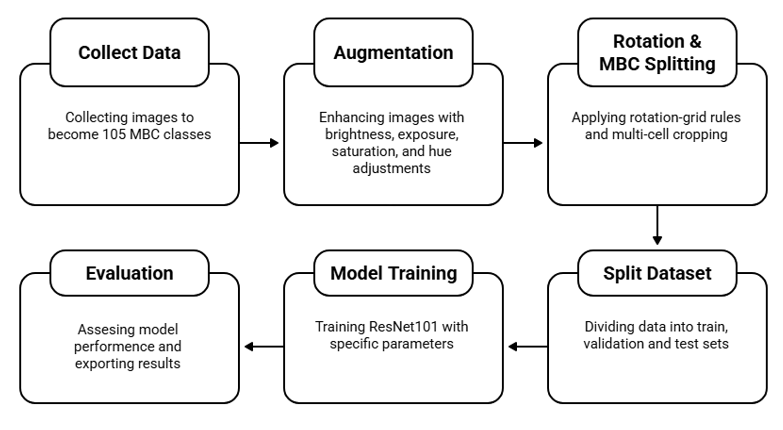

Rotation correction is a pre-processing step that is essential to correcting the subtle skew caused by the image acquisition process [39]. This process can lead to misclassification. This normalization is performed semi-automatically through an interactive graphical interface (GUI), where the user selects a precise rotation angle (≈0.1°) with the help of a visual guideline (crosshair/grid) to align the row and column structure of the Braille dots with the image axis (Figure 3). The operation utilizes the OpenCV library, employing the functions cv2.getRotationMatrix2D to calculate the rotation matrix and cv2.warpAffine to apply the affine transformation. The resultant output is a rotation-normalized Braille image that is then stored as a baseline to mitigate the risk of misclassification caused by spatial misalignment.

Figure 3. Braille Image Initial Rotation Correction Process Using ipywidgets and OpenCV Library

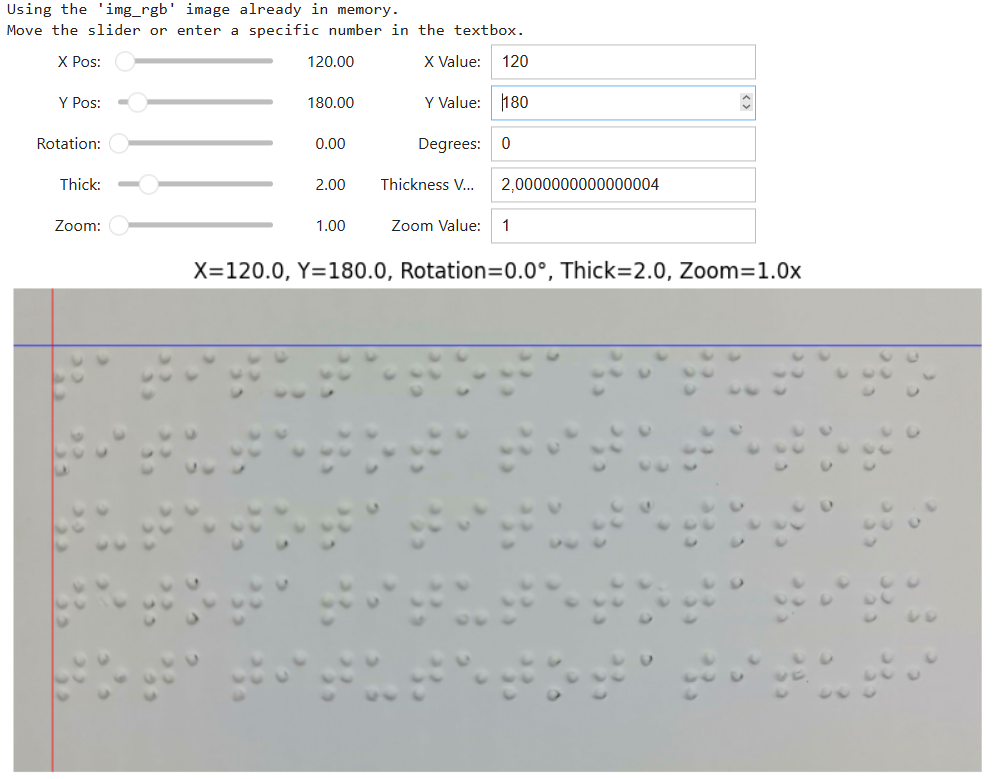

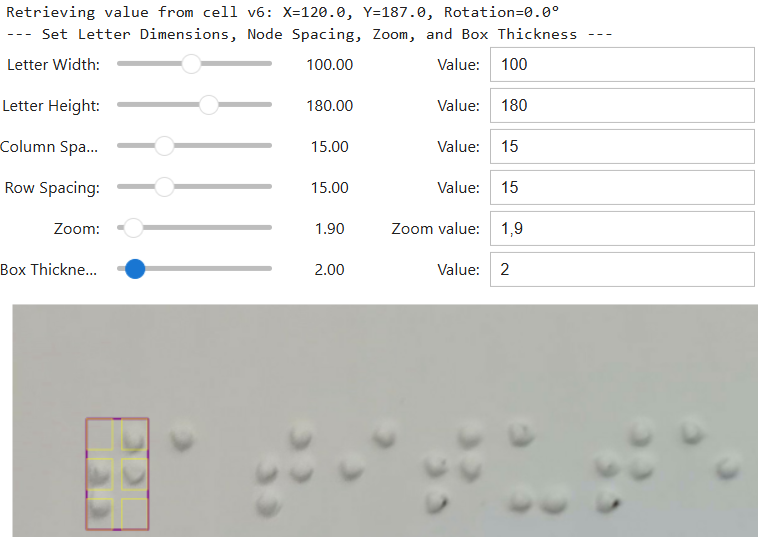

- Grid and Cell Parameter Determination

A procedural step within normalization of the braille structure is the subsequent assignment of grid and cell parameters (Figure 4). This process utilizes an interactive Grid Generator (GUI) that allows real-time calibration of anchor points ( ,

,  ), cell dimensions (

), cell dimensions ( ,

,  ), and column/row spacing via dynamic sliders. It is imperative to note that supplementary ipywidgets controls are utilized for the purpose of making precise adjustments to the padding and spacing parameters. This verified grid consistency ensures that image segmentation is executed with maximum spatial precision, which is a vital prerequisite for the extraction of uniform and consistent MBC bounding boxes as input for ResNet-101 training. The grid calibration process assumes successful dot segmentation under controlled acquisition conditions. In cases of extreme glare or shadow occlusion where thresholding fails and a valid grid cannot be constructed, such samples are treated as failure cases and excluded from further processing to prevent error propagation.

), and column/row spacing via dynamic sliders. It is imperative to note that supplementary ipywidgets controls are utilized for the purpose of making precise adjustments to the padding and spacing parameters. This verified grid consistency ensures that image segmentation is executed with maximum spatial precision, which is a vital prerequisite for the extraction of uniform and consistent MBC bounding boxes as input for ResNet-101 training. The grid calibration process assumes successful dot segmentation under controlled acquisition conditions. In cases of extreme glare or shadow occlusion where thresholding fails and a valid grid cannot be constructed, such samples are treated as failure cases and excluded from further processing to prevent error propagation.

|

|

(a) | (b) |

Figure 4. Grid Assignment Process (a) and Cell Parameters to map Braille structures (b)

- Split Data

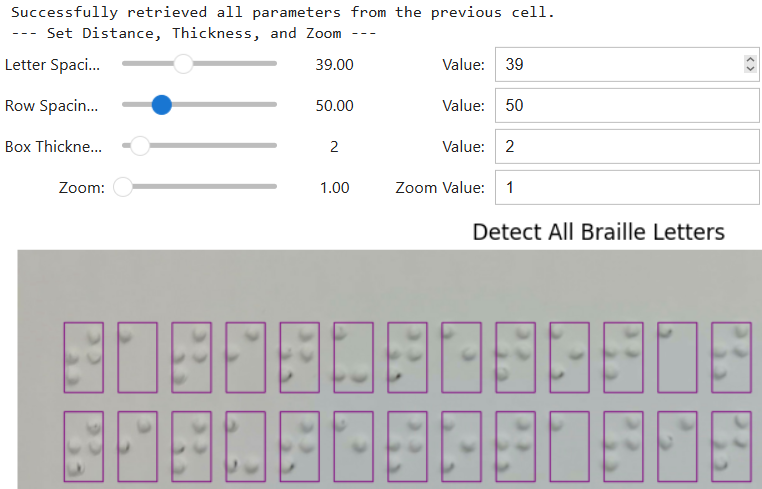

The pre-processing process is concluded with the precise grid definition, which results in the image being divided into character patches. The tool automatically calculates the slice coordinates [y1: y2, x1:x2] of the grid for each Braille cell (or multi-cell block, as appropriate). Subsequently, each patch is extracted and stored in a sequential naming scheme. This procedure is technically crucial, given that the CNN model relies on protrusion shading patterns (rather than tactile data). Consequently, consistency of orientation and relative position of points is imperative. Consequently, the implementation of rotational normalization in conjunction with grid-based splitting effectively mitigates spatial jitter, thereby ensuring that the CNN is exposed to MBC patterns that are both highly homogeneous and standardized. This homogeneity is demonstrated to minimize confusion between classes that have similar dot patterns, thus serving as a vital prerequisite for maximizing the effectiveness and generalizability of the ResNet-101 model.

Post-splitting (Figure 5), the 89x89 pixel MBC character patches are to be organized into discrete sub-folders, meticulously labeled according to the 105 MBC classes. This hierarchical data structure is a standard format required by CNN frameworks, such as TensorFlow and PyTorch. This configuration is paramount because these frameworks automatically interpret folder names as ground-truth labels during training, ensuring that the model learns the correct associations between visual features and their corresponding MBC classes. The dataset was partitioned using a stratified split of 70% for training, 20% for validation, and 10% for testing to preserve class distribution across all subsets. All subsets share the same spatial resolution (89x89) to ensure architectural consistency, while photometric augmentation is applied exclusively to the training set to preserve the realism and integrity of validation and test evaluations.

Figure 5. Image Splitting Process based on slice coordinates

- Model Training

The model training process utilizes the ResNet-101 architecture due to its proven ability to handle the complexity of Braille features and overcome the vanishing gradient problem through its residual connections (Figure 6). The ResNet-101 architecture was configured to perform a 105-class MBC classification task. In this architecture, the fourth stage consists of 23 residual blocks, enabling deep feature extraction while maintaining stable gradient flow, followed by global average pooling and a fully connected classification layer.

Figure 6. CNN Architecture Model with ResNet-101

The training phase was meticulously designed as a rigorous comparative study, wherein the model underwent training separately on nine data subsets, the original dataset and eight variations of single-dimensional augmentation. The variations encompassed brightness (25%), exposure (20%), saturation (40%), and hue (30%) conditions [12]. The optimal hyperparameter configuration (batch_size = 32 and epochs = 300) established in the preliminary study was consistently maintained across all training runs [16]. This specific configuration, in conjunction with the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 1×10⁻⁴ and the categorical cross-entropy loss function, enabled a precise evaluation of the impact of each type of photometric perturbation simulated by the nine datasets on ResNet-101's generalization capability and the stabilization of the Multi Braille Character (MBC) classification performance of 105 classes. All experiments were conducted using the PyTorch framework in Python on the Google Collab platform, utilizing an NVIDIA A100 GPU, which enables efficient large-scale model training.

The confusion-matrix approach was used to assess classification performance [18],[34]. The MBC classifier using the multi-class confusion matrix  with

with  , where

, where  counts test images of true class

counts test images of true class  predicted as class

predicted as class  . Overall performance is reported as Accuracy. For class-wise analysis (one-vs-rest): for each class

. Overall performance is reported as Accuracy. For class-wise analysis (one-vs-rest): for each class  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  , with

, with  . Accuracy is the proportion of correct decisions.

. Accuracy is the proportion of correct decisions.  and

and  measure reliability and coverage for class

measure reliability and coverage for class  .

.  is the harmonic mean of Precisionk and

is the harmonic mean of Precisionk and  . All metrics are expressed in percent (×100) [40].

. All metrics are expressed in percent (×100) [40].

- RESULT AND DISCUSSION

- Collect Data

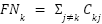

The dataset collected (Figure 7) during the data collection phase contains 21 images of braille sheets comprising braille characters that will be processed in the subsequent stage. This curated set constitutes the input to the preprocessing.

Figure 7. One of the results of collecting braille sheets

- Augmentation

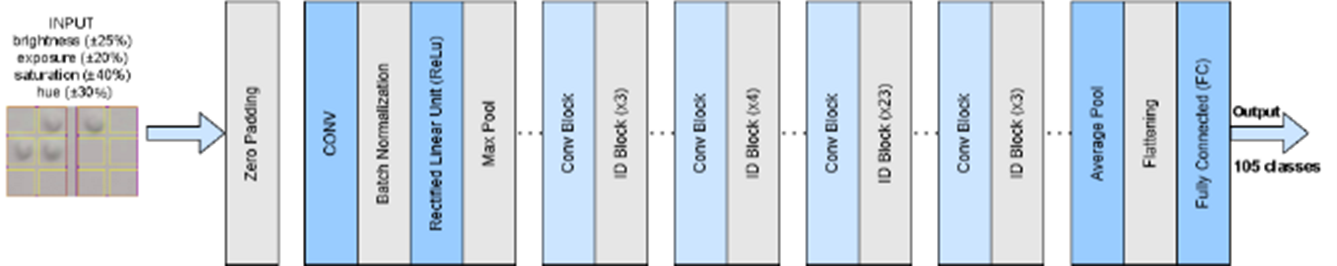

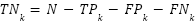

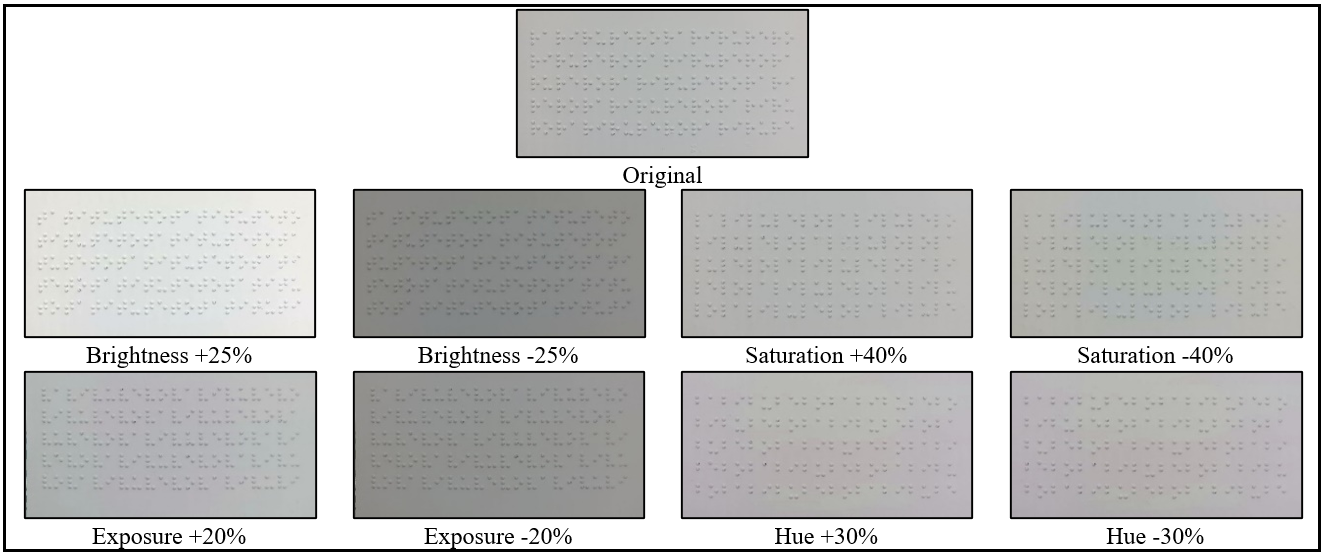

The second stage involves augmenting the original dataset of 21 images with four types of augmentation: brightness (±25%), exposure (±20%), saturation (±40%), and hue (±30%). This augmentation process resulted in the creation of 210 Braille sheet images consisting of 21 original sheet images and 189 augmented sheet images (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Sample of Data Original Image and Augmentation Brightness, Exposure, Saturation and Hue

- Data rotation,Transformation, Grid, and Cell Parameter Determination

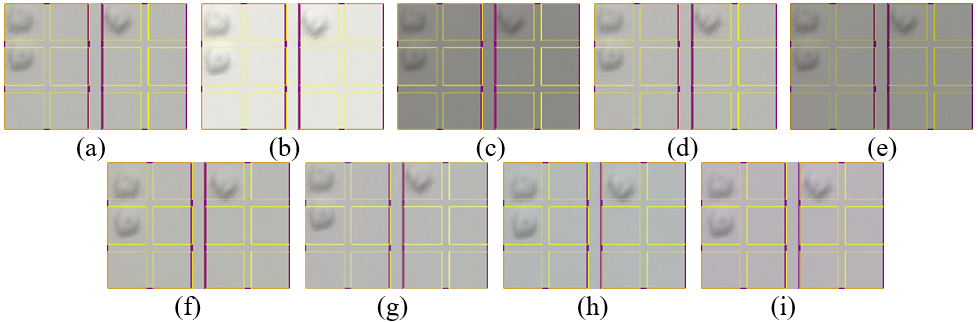

The outcome of the third stage is an augmented image dataset of Braille sheets that have been rotated with the assistance of visual guidelines. The results are stored as a baseline to mitigate the risk of misclassification caused by spatial misalignment. In the next stage, the results of determining the grid and cell parameters are obtained in the form of MBC structure mapping, which will be used for processing. The fifth stage of data preprocessing is the final stage, which involves the division of data. Figure 9 shows the flow of dataset creation. This process yields MBC images that exhibit a consistent grid and dimension, measuring 89x89 pixels. This process produces 105 sub-directories for each augmentation type, which serve as containers for the training data. As a result, the number of datasets, which initially consisted of only 1,050 original MBC images, increased to 9,450 augmented MBC images. Figure 10 is the result of the process of rotation, grid and cutting braille based on the grid to form the MBC dataset.

Figure 9. Workflow of dataset construction for MBC recognition, illustrating alphabet selection, photometric augmentation, sheet collection, and extraction of 9,450 Multi-Braille Character (MBC) samples from 189 Braille sheets

Figure 10. The result of the image cutting process based on the grid with augmentasion of original (a), brightness +25% (b), brightness -25% (c), exposure +20% (d), exposure -20% (e), saturation +40% (f), saturation -40% (g), hue +30% (h) and hue -30% (i)

- Model Training and Evaluation

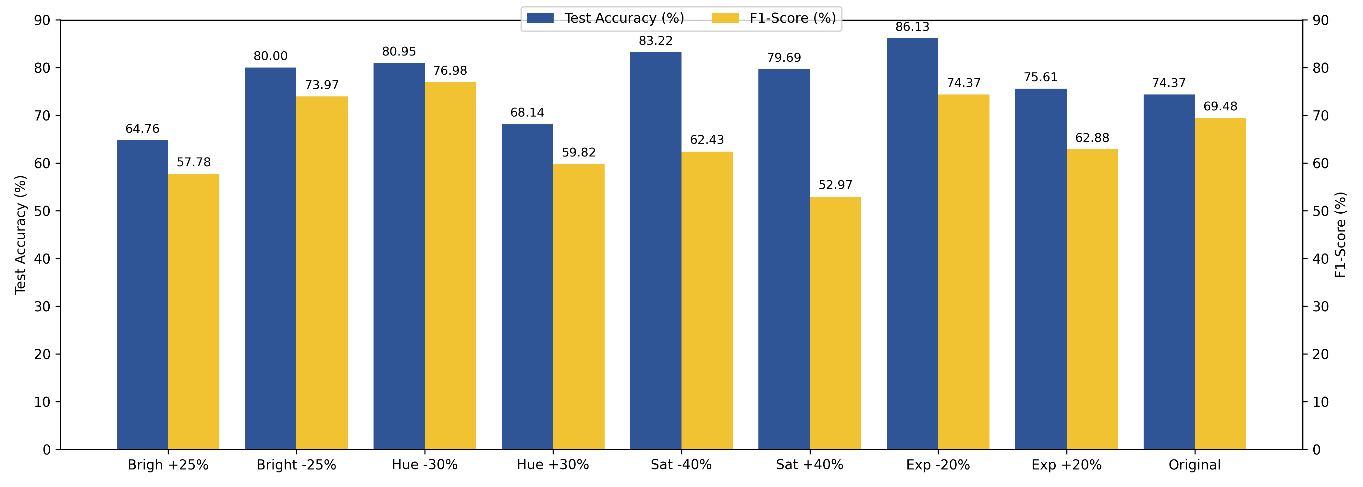

The training process is carried out using the ResNet101 architecture to get the best model from the input data in the form of datasets that have been augmented with brightness (±25%), exposure (±20%), saturation (±40%), and hue (±30%) as well as the original dataset. Visual analysis of the bar charts comparing performance metrics (Test Accuracy and F1-Score) and training time efficiency (Time) for each individual augmentation scenario revealed substantial trade-offs. It is generally seen that F1-Score in almost all individual scenarios is lower than Test Accuracy, corroborating the importance of F1-Score as a more honest metric to measure the stability of multi-class classifications (105 MBC classes). Figure 11 employs dual y-axes to clearly distinguish Test Accuracy and F1-Score, which represent different evaluation metrics with distinct interpretative meanings. This visualization avoids potential misinterpretation that may arise when both metrics are plotted on a single axis.

Figure 11. Comparison of Test Accuracy and F1-Score across different photometric augmentation strategies. Test Accuracy is plotted on the left y-axis, while F1-Score is shown on the right y-axis to account for their different scales and evaluation meanings

Evaluation of the effectiveness of individual data augmentation techniques showed a significant trade-off between model accuracy and computational cost. Exposure -20% (Exp -20%) augmentation emerged as the most efficient solution, as it achieved a Test Accuracy of 86.13%-improving the model performance by 11.76% compared to the Original base model (74.37%) while simultaneously reducing the training time to 14.12 minutes, much shorter than the 22.10 minutes required for the model without augmentation. However, extreme augmentation treatments, such as Bright +25% and Hue +30%, resulted in significant performance degradation. Bright +25% caused the accuracy to plummet to 64.76% (-9.61%), and Hue +30% resulted in 68.14% (-6.23%).

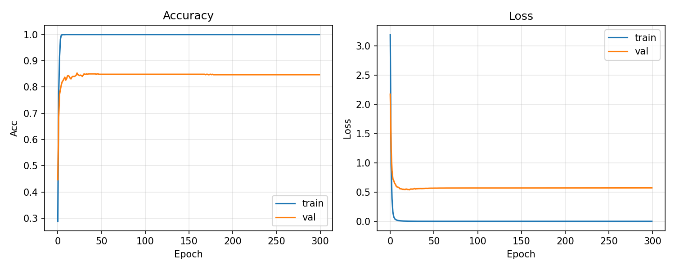

The opposite conclusion is reached when considering aggressive augmentation, which has been found to be detrimental. Specifically, an increase of 25% in brightness results in a 9.61 point percentage decrease in accuracy, to 64.76%, and a 6.23 point percentage decrease in accuracy when the hue is increased by 30%, to 68.14%. It has been observed that both treatments have a tendency to disrupt the subtle shading patterns that serve as the primary cue for CNNs to differentiate between similar point configurations. Over brightening results in the image floor level being elevated, leading to a loss of micro-contrast, while a significant hue shift causes a deviation from the natural color distribution. The performance curves of the ResNet-101 model demonstrate stable and effective learning for the 105-class Multi-Braille Character (MBC) classification task. Figure 12 corresponds to the Exp −20% augmentation setting reported in Table 2.

The training accuracy quickly converges to 100%, while the validation accuracy stabilizes at 86.13%, indicating strong and consistent generalization. This behavior is supported by the loss curves, where the training loss approaches zero and the validation loss converges to a low and stable value (≈0.5). Indicating that the model has good generalisation and does not suffer from severe overfitting.

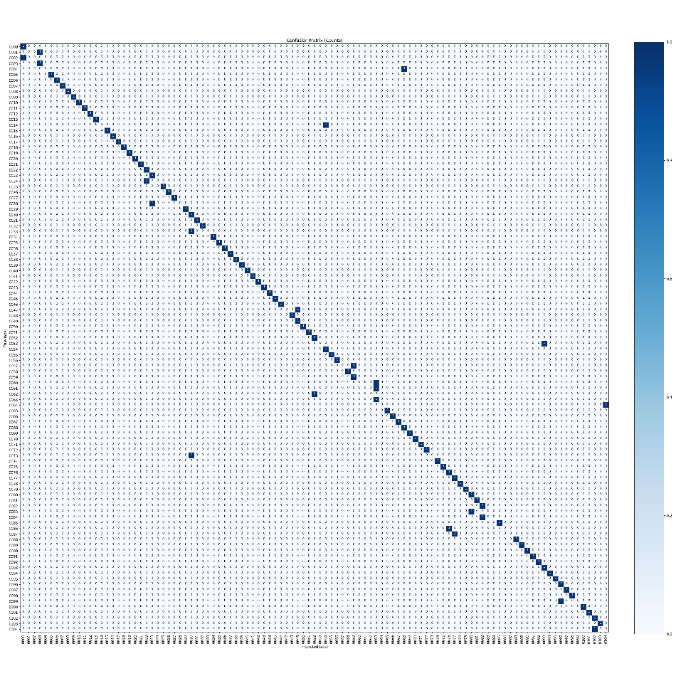

Figure 13 illustrates the row-normalized confusion matrix of the proposed 105-class Multi-Braille Character (MBC) recognition model evaluated on the test set. The pronounced diagonal dominance indicates high per-class recall and stable classification behavior across the majority of MBC classes. The limited off-diagonal responses correspond to systematic misclassifications between MBC pairs with minimal structural differences, typically differing by a single Braille dot or slight positional variation within the same grid cell. These patterns generate highly similar dot–shadow intensity distributions, which can reduce inter-class separability at the feature level. Additional minor confusions are observed near grid boundaries, where small spatial deviations may alter local contrast relationships. The absence of large error clusters confirms that the proposed spatial normalization and controlled photometric augmentation effectively maintain discriminative representations, and that residual errors are primarily attributable to intrinsic visual similarity rather than model overfitting or instability MBC recognition framework.

In summary, the present visualization underscores the pivotal role of the specific augmentation technique in question. It is imperative to note that not all methods are equally beneficial; indeed, some have the potential to be deleterious. The findings indicate that strategies that augment contrast or stabilize visual features, such as reducing exposure, are the most promising approaches for enhancing model accuracy in Multi-Braille Character recognition tasks.

Table 2. The Most Effective Individual Augmentation (Accuracy-Time Trade-off)

Scenario | Time (mint) | Test Accuracy (%) | F1-Score (%) | Improved Accuracy (vs Original) |

Original | 22.10 | 74.37% | 69.48% | 0.00% |

Exp -20% | 14.12 | 86.13% | 74.31% | +11.76% |

Sat -40% | 10.26 | 83.22% | 62.43% | +8.85% |

Hue -30% | 10.30 | 80.95% | 76.98% | +6.58% |

Bright -25% | 12.35 | 80.00% | 73.97% | +5.63% |

Sat +40% | 10.07 | 79.69% | 52.97% | +5.32% |

Exp +20% | 13.87 | 75.61% | 62.88% | +1.24% |

Hue +30% | 10.36 | 68.14% | 59.82% | -6.23% |

Bright +25% | 4.52 | 64.76% | 57.78% | -9.61% |

Figure 12. Model Training Performance for Accuracy and Loss

Figure 13. Confusion Matrix for 105-Class Braille Character Recognition (MBC)

- CONCLUSIONS

The present study empirically evaluates Multi-Braille Character (MBC) classification with a particular emphasis on the ResNet-101 framework applied to a 105-syllable class dataset. The primary methodological contributions lie in the proposed pre-processing and controlled augmentation strategy. Experimental results identify Exposure −20% as the most effective single augmentation, improving test accuracy to 86.13% while reducing training time to 14.12 minutes. Additionally, the use of OpenCV-based semi-automated preprocessing and grid-based splitting effectively mitigates spatial jitter, which is a fundamental prerequisite for robust model generalization. Overall, this approach provides an efficient and reliable pipeline for accurate Braille document digitization under realistic imaging conditions, making it well suited for assistive technologies and large-scale Braille content conversion where robustness to illumination variation and computational efficiency are essential.

DECLARATION

Author Contribution

All authors contributed equally to the main contributor to this paper. All authors read and approved the final paper.

REFERENCES

- T. Kausar, S. Manzoor, A. Kausar, Y. Lu, M. Wasif, and M. A. Ashraf, “Deep Learning Strategy for Braille Character Recognition,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 169357–169371, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3138240.

- A. AlSalman, A. Gumaei, A. AlSalman, and S. Al-Hadhrami, “A Deep Learning-Based Recognition Approach for the Conversion of Multilingual Braille Images,” Computers, Materials & Continua, vol. 67, no. 3, pp. 3847–3864, 2021, https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2021.015614.

- K. Banerjee, A. Singh, N. Akhtar, and I. Vats, “Machine-Learning-Based Accessibility System,” SN Comput Sci, vol. 5, no. 3, p. 294, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-024-02615-9.

- R. Li, H. Liu, X. Wang, and Y. Qian, “Effective Optical Braille Recognition Based on Two-Stage Learning for Double-Sided Braille Image,” In Pacific Rim International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pp. 150–163, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29894-4_12.

- S. Kumari, A. Akole, P. Angnani, Y. Bhamare, and Z. Naikwadi, “Enhanced Braille Display Use of OCR and Solenoid to Improve Text to Braille Conversion,” in 2020 International Conference for Emerging Technology (INCET), pp. 1–5, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/INCET49848.2020.9153996.

- I. G. Ovodov, “Optical Braille Recognition Using Object Detection Neural Network,” in 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW), pp. 1741–1748, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCVW54120.2021.00200.

- Z. Khanam and A. Usmani, “Optical Braille Recognition using Circular Hough Transform,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.00993, 2021, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2107.00993.

- Ramiati, S. Aulia, Lifwarda, and S. N. Nindya Satriani, “Recognition of Image Pattern To Identification Of Braille Characters To Be Audio Signals For Blind Communication Tools,” IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng, vol. 846, no. 1, p. 012008, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/846/1/012008.

- B. Meneses-Claudio, W. Alvarado-Diaz, and A. Roman-Gonzalez, “Classification System for the Interpretation of the Braille Alphabet through Image Processing,” Advances in Science, Technology and Engineering Systems Journal, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 403–407, 2020, https://doi.org/10.25046/aj050151.

- M. Mukhiddinov and S.-Y. Kim, “A Systematic Literature Review on the Automatic Creation of Tactile Graphics for the Blind and Visually Impaired,” Processes, vol. 9, no. 10, p. 1726, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9101726.

- Jonnatan Arroyo, Ramiro Velazquez, Mehdi Boukallel, Nicola Ivan Giannoccaro, and Paolo Visconti, “Design and Implementation of a Low-Cost Printer Head for Embossing Braille Dots on Paper,” International Journal of Emerging Trends in Engineering Research, vol. 8, no. 9, pp. 6183–6190, 2020, https://doi.org/10.30534/ijeter/2020/206892020.

- L. N. Hayati et al., “Improving Indonesian Sign Alphabet Recognition for Assistive Learning Robots Using Gamma-Corrected MobileNetV2,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 350–361, 2025, https://doi.org/10.12928/biste.v7i3.13300.

- A. Mujahid et al., “Real-Time Hand Gesture Recognition Based on Deep Learning YOLOv3 Model,” Applied Sciences, vol. 11, no. 9, p. 4164, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/app11094164.

- A. Kloska, M. Tarczewska, A. Giełczyk, S. M. Kloska, and A. Michalski, “Influence of augmentation on the performance of double ResNet-based model for chest X-rays classification,” Pol J Radiol, vol. 88, pp. 244–250, 2023, https://doi.org/10.5114/pjr.2023.126717.

- B. Li, Y. Hou, and W. Che, “Data augmentation approaches in natural language processing: A survey,” AI Open, vol. 3, pp. 71–90, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aiopen.2022.03.001.

- M. Ayu et al., “Generalized Deep Learning Approach for Multi Braille Character (MBC) Recognition,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 434–449, 2025, https://doi.org/10.12928/biste.v7i3.13891.

- I Made Agus Dwi Suarjaya, B. A. Wiratama, and Ayu Wirdiani, “Sistem Pengenalan Huruf Braille Menggunakan Metode Deep Learning Berbasis Website,” JITSI : Jurnal Ilmiah Teknologi Sistem Informasi, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 93–99, 2024, https://doi.org/10.62527/jitsi.5.3.244.

- A. A. Wicaksana and A. N. Handayani, “Comparation Analysis of Otsu Method for Image Braille Segmentation : Python Approaches,” Indonesian Journal of Data and Science, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 175–183, 2025, https://doi.org/10.56705/ijodas.v6i2.268.

- Y. Xia, R. Xie, X. Wu, Y. Zhao, P. Sun, and H. Chen, “The role of phonological awareness, morphological awareness, and rapid automatized naming in the braille reading comprehension of Chinese blind children,” Learn Individ Differ, vol. 103, p. 102272, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2023.102272.

- G. Liu, S. Tian, Y. Mo, R. Chen, and Q. Zhao, “On the Acquisition of High-Quality Digital Images and Extraction of Effective Color Information for Soil Water Content Testing,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 9, p. 3130, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/s22093130.

- S. Shokat, R. Riaz, S. S. Rizvi, I. Khan, and A. Paul, “Characterization of English Braille Patterns Using Automated Tools and RICA Based Feature Extraction Methods,” Sensors (Basel), vol. 22, no. 5, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/s22051836.

- S. S. M., S. A., J. Raju, and R. M. George, “BrailleSegNet: A novel methodology for Braille dataset generation and character segmentation,” Displays, vol. 90, p. 103145, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.displa.2025.103145.

- A. Al-Salman and A. AlSalman, “Fly-LeNet: A deep learning-based framework for converting multilingual braille images,” Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 4, p. e26155, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26155.

- N. Elaraby, S. Barakat, and A. Rezk, “A generalized ensemble approach based on transfer learning for Braille character recognition,” Inf Process Manag, vol. 61, no. 1, p. 103545, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2023.103545.

- E. M. Torralba, “Fibonacci Numbers as Hyperparameters for Image Dimension of a Convolu-tional Neural Network Image Prognosis Classification Model of COVID X-ray Images,” International Journal of Multidisciplinary: Applied Business and Education Research, vol. 3, no. 9, pp. 1703–1716, 2022, https://doi.org/10.11594/ijmaber.03.09.11.

- S. Roy et al., “Fibonacci-Net: A Lightweight CNN model for Automatic Brain Tumor Classification,” Mar. 2025, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2503.13928.

- K. Panetta, F. Sanghavi, S. Agaian, and N. Madan, “Automated Detection of COVID-19 Cases on Radiographs using Shape-Dependent Fibonacci-p Patterns,” IEEE J Biomed Health Inform, vol. 25, no. 6, pp. 1852–1863, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2021.3069798.

- B.-M. Hsu, “Braille Recognition for Reducing Asymmetric Communication between the Blind and Non-Blind,” Symmetry (Basel), vol. 12, no. 7, p. 1069, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12071069.

- V. P. Revelli, G. Sharma, and S.Kiruthika devi, “Automate extraction of braille text to speech from an image,” Advances in Engineering Software, vol. 172, p. 103180, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advengsoft.2022.103180.

- C. Li and W. Yan, “Braille Recognition Using Deep Learning,” in 2021 4th International Conference on Control and Computer Vision, pp. 30–35, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1145/3484274.3484280.

- L. Lu, D. Wu, J. Xiong, Z. Liang, and F. Huang, “Anchor-Free Braille Character Detection Based on Edge Feature in Natural Scene Images,” Comput Intell Neurosci, vol. 2022, pp. 1–11, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/7201775.

- Z. Tian et al., “A Survey of Deep Learning-Based Low-Light Image Enhancement.,” Sensors (Basel), vol. 23, no. 18, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/s23187763.

- Z. Jingchun, G. Eg Su, and M. Shahrizal Sunar, “Low-light image enhancement: A comprehensive review on methods, datasets and evaluation metrics,” Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences, vol. 36, no. 10, p. 102234, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksuci.2024.102234.

- K. Alomar, H. I. Aysel, and X. Cai, “Data Augmentation in Classification and Segmentation: A Survey and New Strategies,” J Imaging, vol. 9, no. 2, p. 46, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging9020046.

- J. Wu, B. Ding, B. Zhang, and J. Ding, “A Retinex-based network for image enhancement in low-light environments,” PLoS One, vol. 19, no. 5, p. e0303696, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303696.

- L. Lu, D. Wu, J. Xiong, Z. Liang, and F. Huang, “Anchor-Free Braille Character Detection Based on Edge Feature in Natural Scene Images,” Comput Intell Neurosci, vol. 2022, pp. 1–11, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/7201775.

- S. Shokat, R. Riaz, S. S. Rizvi, A. M. Abbasi, A. A. Abbasi, and S. J. Kwon, “Deep learning scheme for character prediction with position-free touch screen-based Braille input method,” Human-centric Computing and Information Sciences, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 41, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13673-020-00246-6.

- W. Hassan, J. B. Joolee, and S. Jeon, “Establishing haptic texture attribute space and predicting haptic attributes from image features using 1D-CNN,” Sci Rep, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 11684, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38929-6.

- J. Huang, K. Zhou, W. Chen, and H. Song, “A pre-processing method for digital image correlation on rotating structures,” Mech Syst Signal Process, vol. 152, p. 107494, May 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2020.107494.

- Y. Ho and A. Mostafavi, “Multimodal Mamba with multitask learning for building flood damage assessment using synthetic aperture radar remote sensing imagery,” Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering, vol. 40, no. 26, pp. 4401–4424, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1111/mice.70059.

Made Ayu Dusea Widyadara (Grid-Calibrated Patch Learning for Braille Multi-Character Recognition)