ISSN: 2685-9572 Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro

Vol. 8, No. 1, February 2026, pp. 15-32

Modified Starch-Based Materials for Sustainable Food Packaging

Isnainul Kusuma 1, Safinta Nurindra Rahmadhia 1, Alfian Ma’arif 2, Agus Aktawan 3,

Titisari Juwitaningtyas 1, Noor Hanuni Ramli 4, Samuel Olugbenga Olunusi 4

1 Department of Food Technology, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Indonesia

2 Department of Electrical Engineering, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Indonesia

3 Department of Chemical Engineering, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Indonesia

4 Faculty of Chemical and Process Engineering Technology, Universiti Malaysia Pahang, Malaysia

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 27 October 2025 Revised 30 November 2025 Accepted 19 December 2025 |

|

Food packaging is a significant contributor to plastic waste, prompting a search for sustainable alternatives. Among these alternatives, modified starch-based materials have emerged as promising solutions due to their biodegradability, renewability, and abundance. However, the hydrophilic nature, poor mechanical properties, and limited thermal stability of native starch pose challenges for its use in food packaging. This review explores various modification techniques—chemical, physical, and enzymatic—that enhance the performance of starch-based materials for food packaging. The methods discussed include acetylation, crosslinking, heat-moisture treatments, and enzymatic hydrolysis, each improving the material's strength, flexibility, and barrier properties. Results demonstrate that starch modifications significantly improve the mechanical, thermal, and water vapor barrier properties of packaging films. Notably, the combination of modified starch with other biopolymers such as chitosan or gelatin further enhances these properties, making them suitable for active packaging applications. The incorporation of antimicrobial agents and nanofillers into starch-based films has expanded their functionality, enabling food shelf-life extension and quality monitoring. Despite these advancements, challenges remain in balancing the biodegradability and durability of starch-based films. Future research should focus on optimizing modification processes, enhancing scalability, and addressing regulatory concerns to ensure the commercial viability of modified starch as an eco-friendly packaging material. |

Keywords: Bioactive Compound; Bio-Packaging; Biopolymer; Modified Starch; Sustainable Material |

Corresponding Author: Safinta Nurindra Rahmadhia, Food Technology Department, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Jl. Ahmad Yani, Tamanan, Banguntapan, Bantul, Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Email: safinta.rahmadhia@tp.uad.ac.id |

This work is open access under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: I. Kusuma, S. N. Rahmadhia, A. Ma’arif, A. Aktawan, and T. Juwitaningtyas, N. H. Ramli, and S. O. Olunusi, “Modified Starch-Based Materials for Sustainable Food Packaging,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 15-32, 2026, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v8i1.15092 |

- INTRODUCTION

Plastic has been widely used in the packaging industry because it is strong, lightweight, and easy to shape. However, after it’s used, most plastic ends up as waste that doesn’t break down, staying in the environment for hundreds of years. Food packaging is one of the biggest sources of this plastic waste [1][2]. To help reduce the use of plastic in food packaging, we need alternative materials that can do the same function but are more environmentally friendly [3][4].

Growing awareness of environmental protection and circular economy practices has driven researchers and industries to explore biodegradable materials that can replace conventional petroleum-based plastics. Among these alternatives, polysaccharide-based materials such as starch, cellulose, and chitosan have gained significant attention due to their abundance and biodegradability [5][6]. Among these, starch stands out as one of the most promising candidates because of its low cost, renewability, and wide availability from various sources such as corn, potato, cassava, and rice [7][8][9].

Starch, a renewable polysaccharide polymer, has been extensively studied and has attracted significant commercial interest for sustainable packaging applications [10][11]. It has the potential to replace conventional plastics in various applications, particularly in the packaging industry. Its biodegradability, renewability, abundance, and low cost make starch one of the most suitable materials for developing environmentally friendly packaging alternatives [12][13].

Despite these advantages, several limitations hinder the broader commercial application of starch. These include its hydrophilic nature, limited thermal and mechanical stability, rapid degradability, and the presence of strong intra- and intermolecular hydrogen bonding within the polymer chains, all of which affect its melt processability and end-use performance [10],[14]. Starch-based materials are particularly sensitive to moisture, which can lead to poor water vapor barrier properties and reduced tensile strength [15][16]. Although the use of plasticizers can improve melt processability, the overall material performance remains limited under certain conditions.

To overcome these challenges, starch requires modification strategies that enhance its physicochemical, thermal, and mechanical characteristics. Starch can be modified using physical treatments (e.g., annealing, heat-moisture), chemical treatments (e.g., acetylation, oxidation, crosslinking), enzymatic methods, or blending with other biopolymers to improve its performance [17][18]. These approaches aim to reduce water sensitivity, enhance barrier properties, and increase the durability of starch-based films for food packaging.

In recent years, modified starch has shown remarkable improvement in its functional properties, including enhanced tensile strength, flexibility, and water vapor barrier performance, making it comparable to conventional plastics in some applications [19][20]. Incorporation of active agents (such as antimicrobials or natural antioxidants) and nanofillers has further expanded the functionality of starch-based films, allowing the development of active and intelligent packaging systems that can extend food shelf life and monitor food quality [21][22].

This review contributes to provide a comprehensive overview of the various starch modification techniques and their effects on the functional properties of starch-based packaging materials. Emphasis is placed on how chemical, physical, and biological treatments can enhance mechanical, barrier, and thermal properties. The review also discusses recent innovations, applications, and challenges for scaling up modified starch-based materials in the food packaging industry. By highlighting these developments, this article underscores the potential of modified starch as a sustainable and eco-friendly alternative to conventional plastics.

- METHODS

This review is based on literature collected from ScienceDirect and Google Scholar, focusing on publications from 2010 to 2024. Keywords such as "modified starch," "starch-based packaging," "biodegradable food packaging," "chemical modification," "physical modification," and "enzymatic modification" are used to identify relevant studies in titles, abstracts, and keywords. The material included is a peer-reviewed research article, a review paper, and a book chapter that discusses starch modification methods, its effects on material properties, and their application in food packaging. Studies that only focus on real starch, less relevant to packaging, or not reviewed by peers are excluded. After an initial screening of more than 200 results, around 80 relevant and high-quality publications were selected for full review. These sources form the basis for discussing the potential of modified starch in sustainable food packaging.

- RESULT AND DISCUSSION

- Types of Starch Modifications

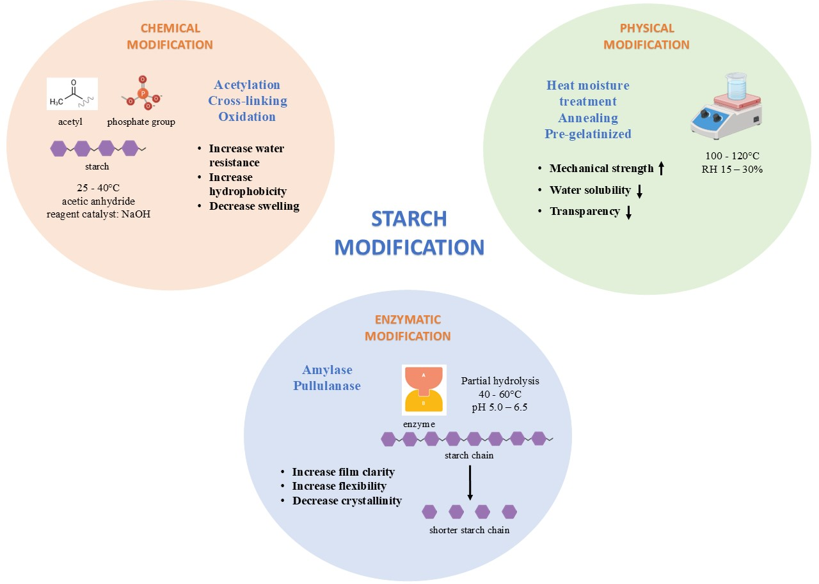

Starch can be modified through chemical, physical, and biological (enzymatic) methods to alter its structure and improve its functional properties for food and industrial applications can be seen in Figure 1 [23]. Each modification approach induces specific changes at the molecular level, particularly in the arrangement and interaction of amylose and amylopectin chains, resulting in altered physicochemical behavior [24][25] .

Figure 1. Starch modification methods

Chemical modification involves the introduction of chemical groups into the starch molecule, typically through processes such as acetylation, cross-linking, oxidation, or phosphorylation. These treatments change the native starch structure by modifying the hydroxyl groups, disrupting the original hydrogen bonding network [23],[26]. As a result, the starch becomes more resistant to enzymatic digestion, leading to an increase in resistant starch content [27]. Additionally, chemical modifications can improve thermal stability, reduce retrogradation, enhance water retention, and provide better textural properties in processed foods [28].

In contrast, physical modification alters starch structure through non-chemical means such as heating, cooling, and mechanical treatment. A common example is autoclaving-cooling, where the starch undergoes gelatinization followed by retrogradation [29][30]. This cycle promotes the rearrangement of amylose chains into more ordered, crystalline regions, forming resistant starch type 3 (RS3) or amylose-lipid complexes (RS5) [31]. Physical treatments improve properties like water holding capacity, swelling power, and thermal stability, making the starch more suitable for applications requiring enhanced texture, shelf life, or slow digestibility [23].

Biological or enzymatic modification employs specific enzymes, such as α-amylase or pullulanase or microbial fermentation to selectively hydrolyze starch molecules [32]. These methods break glycosidic bonds in a controlled manner, producing smaller, functional starch fragments or facilitating the formation of resistant starch type 4 [33]. The enzymatic modification can tailor starch for improved digestibility, prebiotic activity, or enhanced functionality in emulsification and film-forming applications [34]. Overall, each type of starch modification affects the molecular structure in a unique way, contributing to improved nutritional, functional, or sensory properties depending on the intended use of the final product.

- Chemical Modifications

Native starch exhibits promising properties such as biodegradability, renewability, and film-forming ability, making it attractive for sustainable food packaging [35][36]. However, its inherent limitations, such as poor water resistance, low mechanical strength, and high retrogradation tendency, limit its direct application. To overcome these drawbacks, chemical modifications are widely applied to tailor the physicochemical properties of starch and enhance its functionality in food packaging films. Key modification methods include acetylation, oxidation, crosslinking, and graft polymerization, each introducing distinct structural changes that improve film performance [37]. Acetylation involves the introduction of acetyl groups (-COCH₃) into the starch backbone, which reduces hydrogen bonding and increases hydrophobicity [38]. This modification lowers the gelatinization temperature and enhances flexibility and transparency of the films. It also significantly improves water resistance, a critical feature for packaging high-moisture foods [39].

Oxidized starch, produced by treating starch with oxidizing agents like sodium hypochlorite, introduces carbonyl and carboxyl groups, increasing film-forming ability and transparency while also reducing viscosity. However, oxidation can decrease tensile strength due to chain scission, so optimization is crucial [40]. Crosslinking is another widely applied modification that improves starch film stability by forming covalent bonds between starch chains, resulting in a more compact structure [24]. This enhances mechanical strength, thermal stability, and resistance to swelling, making it highly suitable for packaging applications that involve moisture or elevated temperatures [41]. Common crosslinking agents include sodium trimetaphosphate (STMP), citric acid, or epichlorohydrin [42]. Films made from crosslinked starch exhibit less retrogradation and improved durability during storage.

Additionally, graft polymerization, in which synthetic or natural monomers are grafted onto the starch backbone can produce starch-based copolymers with enhanced functional properties [43]. This method enables the introduction of tailored functionalities such as antimicrobial activity, increased hydrophobicity, or UV resistance, depending on the grafted polymer [44]. For instance, grafting acrylic acid or polycaprolactone onto starch can significantly improve film elasticity and barrier properties [37]. Overall, chemical modification of starch is a powerful strategy to overcome the native limitations of starch and create advanced materials tailored for food packaging. Each technique offers specific benefits, and combinations of these methods are often employed to balance mechanical strength, barrier properties, biodegradability, and visual appeal.

- Physical Treatments

Physical modification methods offer an eco-friendly and cost-effective approach to improving the properties of native starch without introducing chemical reagents [17]. Among the most commonly applied physical treatments are heat-moisture treatment (HMT), annealing (ANN), and ultrasonication, each of which alters the crystalline structure and functional behavior of starch granules. These methods are particularly valuable for developing biodegradable packaging materials because they maintain the natural and non-toxic profile of starch while enhancing its mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties [45].

Heat-moisture treatment (HMT) involves subjecting starch to relatively low moisture (usually <35%) and high temperature (90–120 °C) for a specific duration [45]. HMT disrupts the crystalline arrangement and induces molecular reorganization, which leads to reduced swelling power, improved thermal stability, and enhanced film resistance to water vapor permeability [46]. This treatment also contributes to stronger intermolecular bonding, thus increasing tensile strength and decreasing film solubility, important traits for packaging integrity [17]. Similarly, annealing (ANN) is a milder process, performed at higher moisture levels (>60%) and below the gelatinization temperature [47]. Unlike HMT, annealing enhances crystallinity and thermal stability without major structural breakdown. This process typically results in more organized granule structures, reduced amylose leaching, and improved film smoothness and clarity—favorable for packaging where visual appeal matters [48]. When applied to starch used in film formation, ANN-treated starches can yield films with balanced flexibility and transparency [45].

Ultrasonication, on the other hand, is a relatively modern technique that utilizes acoustic cavitation to break hydrogen bonds and alter granule morphology [49]. This method reduces particle size, enhances surface area, and can improve starch dispersion in composite films. Films prepared using ultrasonicated starch typically show higher tensile strength, greater transparency, and lower water vapor permeability, especially when combined with other biopolymers or plasticizers [50]. Additionally, ultrasonication can facilitate the mixing of additives, improving the uniformity of active packaging materials. In summary, physical modification techniques like HMT, ANN, and ultrasonication play a critical role in fine-tuning starch-based materials for food packaging without compromising their biodegradability. These treatments provide a green route to modify structure-function relationships, offering tailored solutions for different food packaging requirements.

- Biological/Enzymatic

Biological or enzymatic modification is a mild, eco-friendly approach to altering starch properties using specific enzymes. This method does not require toxic reagents or extreme conditions, making it particularly attractive for developing safe and sustainable food packaging materials. Among the enzymes used, amylases, a group of hydrolases that break down starch into smaller sugar units are the most widely studied for starch modification [51]. Depending on the type and source, amylases can hydrolyze amylose and amylopectin at different sites, resulting in varied structural and functional changes suitable for packaging applications.

Amylase treatment can significantly affect the molecular weight distribution, viscosity, and film-forming behavior of starch. Controlled hydrolysis using α-amylase can produce low molecular weight starch fragments that improve the dispersion of starch molecules during film casting, leading to more uniform and transparent films. On the other hand, partial degradation by  -amylase or glucoamylase can enhance flexibility and reduce brittleness in starch-based films. This enzymatic tailoring enables the fine-tuning of mechanical properties, such as tensile strength and elongation, as well as barrier properties, including oxygen and water vapor permeability [52]. Furthermore, enzymatically modified starch often exhibits better compatibility with other biopolymers, such as chitosan, gelatin, or polyvinyl alcohol, due to increased hydroxyl group availability. This can enhance crosslinking or blending efficiency, resulting in composite films with superior functionality. For instance, films derived from enzyme-treated starch have been reported to show improved thermal stability and greater uniformity in microstructure, which are essential for food protection during storage and transport [53].

-amylase or glucoamylase can enhance flexibility and reduce brittleness in starch-based films. This enzymatic tailoring enables the fine-tuning of mechanical properties, such as tensile strength and elongation, as well as barrier properties, including oxygen and water vapor permeability [52]. Furthermore, enzymatically modified starch often exhibits better compatibility with other biopolymers, such as chitosan, gelatin, or polyvinyl alcohol, due to increased hydroxyl group availability. This can enhance crosslinking or blending efficiency, resulting in composite films with superior functionality. For instance, films derived from enzyme-treated starch have been reported to show improved thermal stability and greater uniformity in microstructure, which are essential for food protection during storage and transport [53].

Biological treatment also aligns well with green chemistry principles, as it reduces energy consumption and avoids environmental hazards associated with synthetic reagents. Moreover, since many of these enzymes are GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe), the resulting materials are highly suitable for direct food contact [54]. However, challenges remain in terms of controlling the degree of hydrolysis and ensuring batch-to-batch consistency, which are critical for industrial scalability [55]. In conclusion, enzymatic modification using amylase presents a promising strategy for customizing starch for intelligent and active food packaging. It offers precision, safety, and environmental compatibility, supporting the transition to biodegradable and high-performance alternatives to petroleum-based plastics.

- Improvement of Functional Properties

- Mechanical Properties

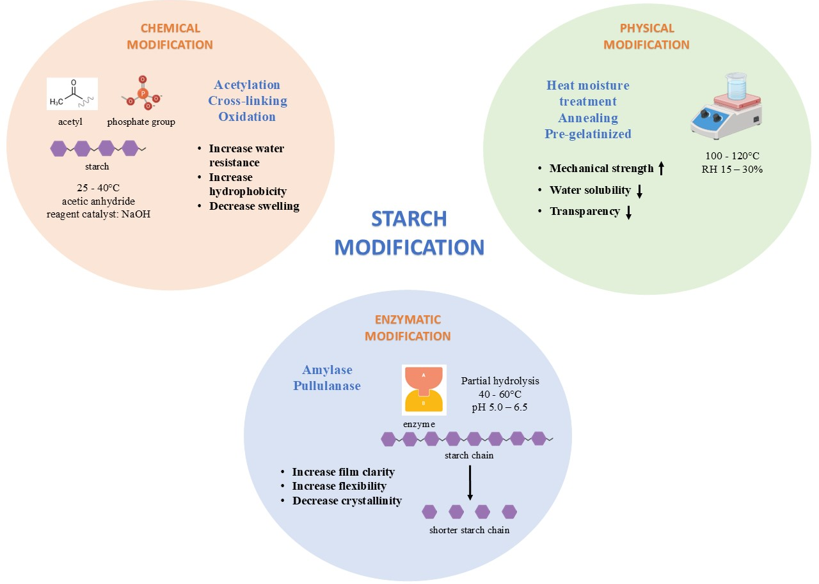

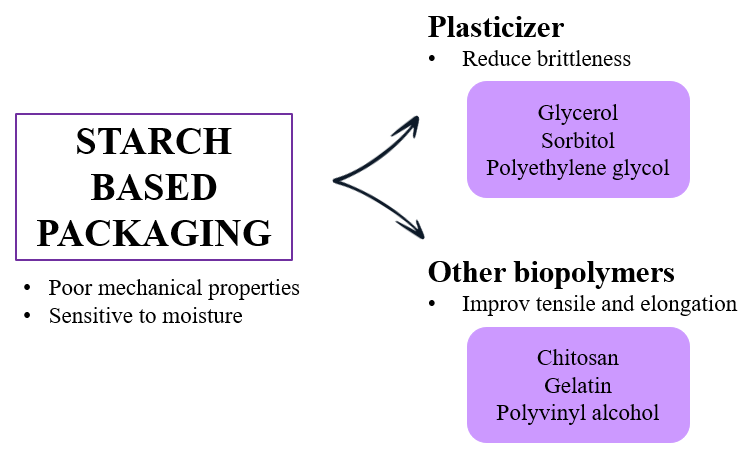

One of the main limitations of native starch in food packaging applications is its poor mechanical performance, particularly its brittleness and sensitivity to moisture. Tensile strength, elongation at break, and flexibility are critical parameters in determining the suitability of starch-based films for packaging, as they influence the film’s ability to withstand stress during handling, storage, and transportation. Unmodified starch tends to form rigid and fragile films due to strong hydrogen bonding between starch chains, which limits its use in flexible packaging [56]. To address this, various modification techniques have been employed to enhance the mechanical behavior of starch films, either by chemically modifying the starch structure or by blending it with other biopolymers or plasticizers (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Modification materials to improve mechanical properties of starch-based film

Chemical modifications, such as acetylation, oxidation, and crosslinking, have been widely used to reduce intermolecular interactions and improve film flexibility. Acetylated starch, for instance, incorporates acetyl groups that reduce hydrogen bonding, resulting in increased elongation at break and improved flexibility without significantly compromising tensile strength [38]. Crosslinking, on the other hand, creates a more robust and less water-sensitive network by introducing covalent bonds between polymer chains, thereby enhancing tensile strength and film durability [57][58]. These modifications not only improve the mechanical integrity of the films but also help stabilize the material under varying humidity conditions, which is crucial for food packaging applications.

Another effective strategy is the incorporation of plasticizers such as glycerol, sorbitol, or polyethylene glycol. These compounds reduce brittleness by increasing the free volume between starch chains, leading to enhanced chain mobility and flexibility. However, the amount and type of plasticizer must be optimized, as excessive plasticizer content can lead to phase separation, stickiness, and reduced tensile strength [57],[59]. The right balance allows for the development of films with sufficient tensile strength to resist tearing while still maintaining flexibility for practical use.

Blending starch with other biopolymers, such as chitosan, gelatin, or polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), has also proven effective in improving mechanical performance. These composite films exhibit improved tensile and elongation properties due to the synergistic interactions between starch and the secondary polymer [60]. For example, starch–gelatin films demonstrate enhanced elasticity and strength due to the protein’s plasticizing effect and ability to form intermolecular hydrogen bonds [61]. The resulting materials are better suited to a variety of packaging formats, from pouches to wraps, and are more resistant to mechanical failure under load.

Overall, improving the mechanical properties of starch-based films through modification, plasticization, and blending is essential for broadening their commercial viability in food packaging. These enhancements allow the films to meet industry standards while maintaining biodegradability and safety. Future research should continue to focus on optimizing the composition and processing conditions to achieve high-performance packaging materials with both functionality and sustainability.

- Barrier Properties

Barrier properties, particularly water vapor permeability (WVP) and oxygen permeability, are critical factors in determining the effectiveness of food packaging materials. These properties control the rate at which moisture and gases (especially oxygen) pass through the packaging film, directly affecting the shelf life, texture, and safety of food products [62]. Native starch films generally exhibit poor moisture barrier properties due to their hydrophilic nature, which leads to high WVP and limited use in packaging applications for high-moisture or oxygen-sensitive foods [63]. To address this, various modification techniques have been implemented to enhance starch film resistance against water and gas permeation.

Chemical modifications, such as acetylation or crosslinking, are known to reduce the availability of hydroxyl groups in the starch structure, thereby decreasing its affinity for water. These modifications help create a more compact and less polar matrix, which significantly reduces WVP and improves oxygen barrier performance [64]. For example, oxidized and acetylated starch-based films have shown improved moisture resistance and reduced permeability, making them more suitable for products like dried snacks or baked goods [65]. Similarly, crosslinked starch networks enhance film integrity, providing greater resistance to diffusion pathways for gas and water molecules.

Another effective strategy involves the incorporation of hydrophobic additives or nanofillers, such as lipids, waxes, or nanoparticles like  and montmorillonite clay. These components reduce the hydrophilicity of starch matrices and create tortuous paths that slow down vapor and gas transmission. The presence of clay nanoparticles in particular has been shown to significantly enhance the oxygen barrier properties by forming layered structures that block molecular diffusion [66]. Moreover, combining starch with other biopolymers, such as chitosan or polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), can synergistically improve barrier behavior by enhancing the film’s density and reducing free volume within the matrix [67].

and montmorillonite clay. These components reduce the hydrophilicity of starch matrices and create tortuous paths that slow down vapor and gas transmission. The presence of clay nanoparticles in particular has been shown to significantly enhance the oxygen barrier properties by forming layered structures that block molecular diffusion [66]. Moreover, combining starch with other biopolymers, such as chitosan or polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), can synergistically improve barrier behavior by enhancing the film’s density and reducing free volume within the matrix [67].

In addition to modifying the composition, processing methods such as casting, extrusion, or lamination also influence barrier properties. Films produced under optimized drying or extrusion conditions exhibit smoother surfaces and lower porosity, both of which contribute to decreased permeability. However, a trade-off often exists: improving water resistance may compromise film flexibility or transparency. Thus, achieving an optimal balance of properties is essential for meeting specific packaging requirements.

In conclusion, enhancing the barrier properties of starch-based films is crucial for extending food shelf life and expanding application potential. Through a combination of chemical modifications, nanocomposite formulations, and processing innovations, researchers have successfully developed starch films with significantly reduced WVP and oxygen permeability. Continued research is needed to ensure these improvements can be scaled sustainably while maintaining biodegradability and food safety standards.

- Thermal Properties

Thermal stability is a critical factor in the application of starch-based films for food packaging, particularly when the packaging is subjected to high-temperature processes such as thermal sealing, sterilization, or hot filling [68]. Native starch films, while biodegradable and non-toxic, generally suffer from low thermal stability due to their semicrystalline structure and sensitivity to moisture. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) are widely used to evaluate the thermal behavior of starch films, providing insights into their degradation temperatures, thermal transitions, and heat resistance under processing or storage conditions [69].

To improve thermal stability, chemical modifications like crosslinking, acetylation, or oxidation have been employed to restructure the starch polymer chains. Crosslinking in particular creates a more thermally stable matrix by forming covalent bonds between starch molecules, increasing the onset degradation temperature observed in TGA profiles. For instance, films made from crosslinked starch typically exhibit two main degradation stages: initial moisture loss at 100°C and major decomposition between 250–350°C, indicating enhanced thermal stability compared to native starch [70]. DSC studies also reveal higher glass transition temperatures ( ) and melting temperatures (

) and melting temperatures ( ) in modified starch films, reflecting improved resistance to thermal softening [71].

) in modified starch films, reflecting improved resistance to thermal softening [71].

In addition, the incorporation of nanomaterials or secondary biopolymers (e.g., chitosan, cellulose, PVA) into starch matrices has demonstrated significant improvements in thermal performance [72]. Nanoparticles such as  ,

,  , and clay form interactions with starch chains and limit polymer mobility, thus delaying thermal degradation and increasing the heat flow required for thermal transitions [73]. These changes are clearly observed in DSC thermograms as shifts toward higher

, and clay form interactions with starch chains and limit polymer mobility, thus delaying thermal degradation and increasing the heat flow required for thermal transitions [73]. These changes are clearly observed in DSC thermograms as shifts toward higher  and

and  values, while TGA shows delayed weight loss onset, often by 20–30°C compared to control films [74].

values, while TGA shows delayed weight loss onset, often by 20–30°C compared to control films [74].

The plasticizer content also influences thermal behavior. Glycerol and sorbitol, commonly used to improve film flexibility, may lower the  due to increased molecular mobility, potentially compromising thermal stability. However, when used in optimized concentrations and in conjunction with nanofillers or chemical modifications, their negative impact on thermal resistance can be minimized [67]. Thus, thermal property enhancement requires a holistic design of formulation components to achieve both flexibility and thermal resistance.

due to increased molecular mobility, potentially compromising thermal stability. However, when used in optimized concentrations and in conjunction with nanofillers or chemical modifications, their negative impact on thermal resistance can be minimized [67]. Thus, thermal property enhancement requires a holistic design of formulation components to achieve both flexibility and thermal resistance.

In conclusion, enhancing the thermal properties of starch-based films through chemical modifications, nanocomposite design, and polymer blending is essential for their application in real-world packaging environments. Advanced TGA and DSC analyses provide essential data to guide material optimization, ensuring that starch-based packaging materials can endure industrial conditions without compromising safety or performance.

- Transparency/Appearance

Visual appeal plays a vital role in food packaging, influencing consumer perception, product attractiveness, and marketing value. In this regard, transparency and surface appearance are essential characteristics for starch-based films, particularly in applications where visibility of the food product is desired, such as fresh produce, confectionery, or snacks. Native starch films are typically semi-transparent and can appear cloudy or brittle due to the high crystallinity and phase separation of starch polymers [75].

Therefore, enhancing the optical clarity and smoothness of starch-based films has become a key focus in functional property improvement. Various modification techniques have been applied to improve transparency. Chemical modifications, such as acetylation or oxidation, reduce intermolecular hydrogen bonding, resulting in a more homogeneous and amorphous film matrix that enhances light transmittance. For example, acetylated starch films show increased clarity due to their improved compatibility with plasticizers and reduced retrogradation [76]. Likewise, blending with other biopolymers, such as gelatin, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), or chitosan, has been shown to reduce surface irregularities and phase separation, improving film glossiness and overall visual quality [77].

The choice and concentration of plasticizers also significantly impact the appearance of starch films. Glycerol and sorbitol, when added in appropriate amounts, improve flexibility and surface homogeneity, leading to more transparent and smoother films. However, excessive plasticizer content may result in sticky or tacky films with poor optical quality. In contrast, incorporating nanoparticles (e.g.,  ,

,  , montmorillonite) may enhance mechanical and barrier properties but sometimes reduce transparency due to light scattering from dispersed particles [78].

, montmorillonite) may enhance mechanical and barrier properties but sometimes reduce transparency due to light scattering from dispersed particles [78].

Therefore, nanoparticle dispersion must be optimized to avoid visible agglomeration. Moreover, film processing techniques, such as solution casting, drying rate, and film thickness, directly affect surface morphology and clarity. Films with uniform thickness and controlled drying conditions tend to exhibit better light transmission and a smoother surface, while rapid drying or uneven film formation can introduce bubbles or surface defects that hinder transparency [79]. Advanced techniques, such as extrusion-blown film or multilayer film design, are being explored to achieve both good optical properties and functional performance [80].

In conclusion, improving the transparency and appearance of starch-based films is critical not only for aesthetic reasons but also for enhancing consumer trust and product visibility. Through careful selection of starch sources, modification methods, and processing techniques, it is possible to produce biodegradable packaging films that are visually appealing while still offering the necessary mechanical and barrier functions required for food preservation.

- Active and Intelligent Packaging

- Incorporation of Bioactives

The incorporation of bioactive compounds into starch-based films has opened new possibilities in developing active packaging that not only acts as a physical barrier but also contributes to food preservation. Bioactives such as essential oils, antimicrobial agents, and antioxidants can be embedded into starch matrices to provide extended shelf life, inhibit microbial growth, and reduce oxidative degradation in food products [81]-[83]. Modified starch enhances the compatibility of these bioactives within the polymer network, leading to improved dispersion and controlled release. Essential oils such as cinnamon, oregano, clove, ginger, and thyme have demonstrated broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties when incorporated into starch films, making them promising natural alternatives to synthetic preservatives [84]-[86].

Moreover, these bioactive have shown significant antioxidant activity when included in starch-based films, protecting food from lipid oxidation, especially in meat and dairy products. The antioxidative effect is primarily attributed to the presence of phenolic compounds in plant-derived essential oils and extracts [87]-[90]. Their inclusion in the film formulation not only enhances the preservation quality but also contributes to improved functional properties of the films, such as increased barrier resistance and slightly modified flexibility or transparency [91]. Encapsulation techniques or nanoemulsification have also been utilized to improve the stability and release behavior of essential oils within the packaging system [92].

Importantly, the interaction between bioactives and starch matrices is influenced by several factors including the method of starch modification, plasticizer concentration, and environmental conditions like temperature and humidity. A balance must be achieved to ensure the bioactivity remains effective without compromising film integrity. Additionally, sensory impacts such as odor from essential oils must be considered to avoid negatively affecting the packaged food’s quality. Overall, the incorporation of natural bioactives into modified starch-based films not only addresses food safety and shelf life but also aligns with the growing consumer demand for clean-label and environmentally friendly packaging solutions [93]. Table 1 depict the incorporation of bioactive compound in the natural packaging for food product application.

Table1. Application of active packaging on food

Main Component | Bioactive Compound | Function | Sample | Reference |

Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET 12 µm) and Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE 35 µm) | Thymus numidicus essential oil | Antimicrobial | Soft date fruits | [94] |

Brazilian purple yam starch | - | Absorbing exudate and antimicrobial activity | Fresh cheese | [95] |

Crude tangerine pectin /gelatin | Green tea extract | Antioxidant and antibacterial | - | [96] |

Cassava starch, microcellulose, and β-cyclodextrin | Menthol and D-limonene | Antimicrobial | Blueberry | [97] |

Corn starch | ε-polylysine hydrochloride | Antibacterial | Beef | [98] |

- pH-responsive Films

The development of intelligent packaging that can monitor food quality in real-time has gained growing interest, especially with the integration of pH-sensitive natural indicators into starch-based films. Among these, anthocyanins water-soluble pigments found in various fruits and vegetables mare commonly used for their excellent color-changing ability across a wide pH range. When embedded in modified starch matrices, anthocyanins serve as visual indicators of food spoilage by changing color in response to volatile basic compounds (e.g., ammonia or amines) released during protein decomposition [58],[99]. This functionality allows consumers to easily assess freshness without opening the package, promoting both food safety and reduced waste. The examples of starch with bioactive compound for intelligent packaging is present in Table 2.

Table 2. Application of intelligent packaging on food

Main component | Bioactive Compound | Function | Sample | Reference |

Ginger starch | Coconut oil and silver nanoparticles | Biodegradable cast films | - | [100] |

Octenyl succinic anhydride starch/polyvinyl alcohol | Curcumin and Roselle anthocyanins | Freshness monitoring and shelf-life extension | Shrimp and beef | [101] |

Starch and esterified starch | Black rice anthocyanin | Monitor food quality, water quality and soil properties | Pork belly | [102] |

Pea starch and κ-carrageenan | Black raspberry extract | Food freshness monitoring | Pork | [103] |

Carboxymethyl starch/polyvinyl alcohol | Cu-LTE nanocrystal | Monitoring deterioration | Shrimp | [104] |

Anthocyanins typically shift from red in acidic conditions to purple or blue in neutral pH and green or yellow in alkaline environments, making them ideal for freshness detection in perishable foods such as fish, meat, or dairy products [105]-[108]. Starch-based films act as excellent carriers due to their biocompatibility, transparency, and film-forming capabilities, while modification (e.g., crosslinking or blending) can further enhance the retention and stability of anthocyanins during storage [5],[109]. Several studies have demonstrated the successful incorporation of anthocyanins from sources like red cabbage, black rice, and butterfly pea flower into starch matrices to create colorimetric indicators responsive to food spoilage [110]-[113].

However, challenges such as anthocyanin degradation under heat, light, or oxygen exposure still limit commercial applications [114][115]. Recent research has explored solutions like encapsulating anthocyanins with cyclodextrins or incorporating UV-blocking agents to improve their stability [116][117]. Additionally, combining anthocyanins with modified starch and other biopolymers such as chitosan or gelatin can produce more robust films with enhanced barrier and mechanical properties [118][119]. These advancements highlight the potential of starch-based pH-responsive films not only for intelligent packaging but also for applications aligned with consumer demand for natural, sustainable, and informative food systems.

- Nanotechnology Enhancement

The integration of nanotechnology into starch-based packaging has significantly enhanced the functionality and durability of biodegradable films [120]. Nanoparticles such as zinc oxide ( ), titanium dioxide (

), titanium dioxide ( ), and clay are among the most widely used inorganic fillers in starch matrices due to their reinforcing properties and ability to introduce new functionalities [121][122]. These nanomaterials, when evenly dispersed in the polymer network, increase the mechanical strength, thermal stability, and barrier performance of starch films, making them more suitable for food packaging applications [123]. Their nanoscale size enables better interaction with starch chains, thereby creating a compact matrix that hinders the diffusion of water vapor and gases like oxygen.

), and clay are among the most widely used inorganic fillers in starch matrices due to their reinforcing properties and ability to introduce new functionalities [121][122]. These nanomaterials, when evenly dispersed in the polymer network, increase the mechanical strength, thermal stability, and barrier performance of starch films, making them more suitable for food packaging applications [123]. Their nanoscale size enables better interaction with starch chains, thereby creating a compact matrix that hinders the diffusion of water vapor and gases like oxygen.

Among these,  nanoparticles are particularly valued for their strong antimicrobial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, offering active packaging functions. Additionally,

nanoparticles are particularly valued for their strong antimicrobial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, offering active packaging functions. Additionally,  nanoparticles provide not only UV-blocking ability but also antimicrobial properties under UV exposure through photocatalytic activity, helping to protect sensitive food products from light-induced spoilage [124]. On the other hand, clay nanoparticles such as montmorillonite or halloysite act as effective reinforcements by forming layered structures within the starch matrix that create a tortuous path for moisture and gas molecules, thereby improving barrier properties without sacrificing biodegradability [125].

nanoparticles provide not only UV-blocking ability but also antimicrobial properties under UV exposure through photocatalytic activity, helping to protect sensitive food products from light-induced spoilage [124]. On the other hand, clay nanoparticles such as montmorillonite or halloysite act as effective reinforcements by forming layered structures within the starch matrix that create a tortuous path for moisture and gas molecules, thereby improving barrier properties without sacrificing biodegradability [125].

However, to fully benefit from these nanoparticles, dispersion and compatibility within the starch film must be carefully optimized. Surface modification of nanoparticles or the use of plasticizers and compatibilizers is often necessary to prevent aggregation and maintain transparency and flexibility of the films [126]. Moreover, while these nanoparticles improve functionality, concerns related to migration, toxicity, and regulatory approval remain key issues for commercial application, especially for direct food contact materials. Continued research is needed to develop safe, scalable, and eco-friendly nanocomposite starch films, ensuring that the advantages of nanotechnology can be harnessed without compromising food safety or environmental sustainability [127].

- Blending with Other Biopolymers

In recent years, modified starch-based composites have emerged as promising candidates for sustainable food packaging, especially when blended with other biopolymers such as chitosan, gelatin, alginate, and cellulose [127]. These combinations aim to overcome the inherent limitations of starch films namely their poor mechanical strength, high water sensitivity, and suboptimal barrier properties while leveraging the complementary advantages of each biopolymer [128][129]. For example, chitosan brings intrinsic antimicrobial activity, thanks to its polycationic structure that disrupts microbial cell membranes, whereas gelatin contributes excellent film-forming capability, flexibility, and optical clarity due to its proteinaceous nature [130].

The synergistic blending of starch with chitosan, gelatin, alginate, and cellulose has been shown to significantly improve the mechanical, barrier, and antimicrobial properties of resulting films, making them more suitable for active food packaging applications [131][132]. For instance, composite films of corn starch, chitosan, and cellulose nanocrystals displayed enhanced tensile strength, reduced water vapor permeability, and superior antimicrobial function when compared to pure starch films [133][134]. Moreover, gelatin–chitosan composites effectively prolonged shelf life of perishable foods by reducing microbial spoilage, improving antioxidant capacity, and enhancing film integrity under various storage conditions [135][136].

Alginate and cellulose-based reinforcements further strengthen these starch–biopolymer matrices, improving structural rigidity, moisture resistance, and durability. Alginate contributes robust gel-forming ability and bio-compatibility, while nanocellulose or cellulose derivatives dramatically raise mechanical performance and barrier function thanks to their high crystallinity and hydrogen-bond-forming capacity [137] [138]. In active packaging systems, the incorporation of nano-reinforcements (e.g.,  , cellulose nanocrystals, montmorillonite) has also produced films exhibiting improved tensile strength, elasticity, antimicrobial activity, UV protection, and reduced solubility—effectively demonstrating the synergistic benefits of multi-polymer and nanoparticle incorporation [139].

, cellulose nanocrystals, montmorillonite) has also produced films exhibiting improved tensile strength, elasticity, antimicrobial activity, UV protection, and reduced solubility—effectively demonstrating the synergistic benefits of multi-polymer and nanoparticle incorporation [139].

- Degradability and Environmental Impact

Modified starch-based materials are increasingly being explored for sustainable food packaging due to their biodegradability and low environmental impact. In natural conditions such as soil, compost, or aquatic environments, starch-based films can be broken down by microorganisms into carbon dioxide, water, and biomass. This process is largely driven by microbial enzymatic activity targeting the glycosidic bonds of starch molecules [109],[140]. The rate of biodegradation is influenced by environmental factors (temperature, moisture, microbial density), the type of starch modification (e.g., physical, chemical), and the presence of additional biopolymers [141]. Although some modifications, such as cross-linking, may slightly delay degradation by increasing structural stability, the materials remain biodegradable within a reasonable time frame [142]. This feature distinguishes starch-based packaging from conventional plastics, which can persist in the environment for hundreds of years.

Blending modified starch with other biopolymers such as chitosan, gelatin, alginate, or cellulose does not inhibit biodegradability but often enhances it. The hydrophilic nature and biodegradability of these natural polymers allow microbial communities to access and break down the matrix more efficiently. Moreover, such blends improve water uptake, enzymatic accessibility, and reduce structural crystallinity, all of which facilitate microbial degradation [143]. In composting systems, starch-based films typically disintegrate within a few weeks, making them suitable for industrial composting programs that meet biodegradability standards like EN 13432 or ASTM D6400 [144]. These materials also pose minimal risk in aquatic environments, where they tend to fragment and decompose faster than synthetic polymers, reducing the accumulation of microplastics.

The life-cycle assessment (LCA) of starch-based packaging materials confirms their environmental benefits compared to petroleum-based plastics. Studies have shown that starch films generally have lower carbon footprints, energy consumption, and ecotoxicity indicators throughout their life cycle [145]. When derived from agro-industrial waste, such as yam, cassava, or corn byproducts, the sustainability is further enhanced by utilizing renewable, non-food biomass and promoting circular economy practices. Nonetheless, LCAs also highlight trade-offs, including potential water usage, competition with food resources (in the case of edible starch), and shorter durability, which may influence the overall environmental balance [146]. Therefore, careful selection of starch sources, processing methods, and end-of-life scenarios is essential to optimize environmental outcomes.

- Challenges and Future Perspective

Despite their environmental advantages, modified starch-based materials face a critical challenge in balancing biodegradability with functional durability. Native starch and its modified derivatives tend to be highly hydrophilic, making them prone to moisture absorption, which weakens mechanical integrity and accelerates degradation under humid conditions [147]. While chemical modifications such as cross-linking or blending with more stable biopolymers like chitosan and cellulose can enhance film strength and barrier properties, these treatments may slow down biodegradability [148]. This trade-off creates a design tension between creating packaging that is durable enough for commercial use yet still capable of degrading efficiently in compost or soil environments [149]. Therefore, the formulation of starch-based films must carefully optimize structural stability during use and rapid disintegration after disposal.

In addition to technical barriers, scalability and cost-effectiveness remain significant obstacles for industrial application. Although starch is an abundant and renewable raw material, the processes involved in modifying it such as physical treatments, chemical functionalization, or blending with performance-enhancing additives can increase production complexity and cost [150]. This may limit the commercial competitiveness of starch-based packaging compared to petroleum-derived plastics, which are produced at scale with mature, cost-efficient infrastructure [151]. Furthermore, the shelf life and moisture sensitivity of starch films often necessitate multilayer or composite structures, further raising material and processing costs. Overcoming these issues requires the development of low-cost modification techniques, the use of agro-industrial byproducts as feedstocks, and the improvement of mechanical and barrier properties through optimized processing [152].

From a regulatory and societal perspective, modified starch-based packaging holds strong promise but requires continued support and standardization. While consumers are increasingly aware of and interested in eco-friendly packaging, confusion persists over terms such as “biodegradable” and “compostable,” especially when the materials require industrial composting facilities to fully degrade [153]. Regulatory frameworks must ensure accurate labeling and provide clear guidelines for safety, performance, and environmental compliance. At the same time, incentives and policies supporting bio-based packaging development alongside public education are essential to foster market confidence and adoption. Moving forward, interdisciplinary collaboration between material scientists, policymakers, and industry stakeholders will be crucial to realizing the full potential of starch-based packaging in reducing plastic pollution and supporting a circular economy.

- CONCLUSIONS

Modified starch presents a highly promising alternative for eco-friendly food packaging due to its biodegradability, renewability, and versatility. Various modification techniques such as chemical, physical, enzymatic, and nanotechnology-based methods have been shown to significantly enhance starch’s mechanical strength, barrier performance, thermal stability, and even active or intelligent functionalities, making it suitable for real-world applications. However, to enable large-scale commercialization, future efforts must focus on developing scalable and cost-effective modification processes, improving long-term material stability, and addressing regulatory and consumer acceptance issues. Successful advancement in this field will require strong collaboration between researchers, industry stakeholders, and policy makers to bridge the gap between laboratory innovations and market-ready solutions.

DECLARATION

Sustainable Development Goals

The suitable development goals can be categorized as Zero hunger (SDG 2), Good health and Well-being (SDG 3), and Responsible Consumption and Production (SDG 12).

Author Contribution

All authors contributed equally to the main contributor to this paper. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Funding

This research was funded by Institute of Research and Community Service, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan through Matching Grant funding with contract number 004/IRMG/LPPM-UAD/IX/2024.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the Institute of Research and Community Service, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan for the financial support to this research through the Matching Grant funding with contract number 004/IRMG/LPPM-UAD/IX/2024.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- S. A. Attaran, A. Hassan, and M. U. Wahit, “Materials for food packaging applications based on bio-based polymer nanocomposites,” J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater., vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 143–173, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1177/0892705715588801.

- G. A. M. Guerrero and M. S. Guerrero, “Biodegradation of Single Use Plastic Waste by Insect Larvae: A Comparative Study of Yellow Mealworms and Superworms,” J. Sci. Agrotechnology, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 61–75, 2023, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.21107/jsa.v1i2.14.

- L. K. Ncube, A. U. Ude, E. N. Ogunmuyiwa, R. Zulkifli, and I. N. Beas, “Environmental Impact of Food Packaging Materials: A Review of Contemporary Development from Conventional Plastics to Polylactic Acid Based Materials,” Materials (Basel)., vol. 13, no. 21, p. 4994, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13214994.

- J. Li, Y. Hou, S. Song, and H. Chen, “Casein-caffeic acid-cellulose nanocrystals composite edible films for microwave food packaging application,” Int. J. Biol. Macromol., p. 149320, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.149320.

- R. Thakur, P. Pristijono, C. J. Scarlett, M. Bowyer, S. P. Singh, and Q. V. Vuong, “Starch-based films: Major factors affecting their properties,” Int. J. Biol. Macromol., vol. 132, pp. 1079–1089, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.03.190.

- R. A. Sari, R. P. Utami, and U. R. G. Natalie, “Exploration of Instant Functional Drinks Based on Angkak and Kidney Bean Flour: Implications on Bioactive Compound and Antioxidant Activity,” J. Agri-Food Sci. Technol., vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 161–167, 2025, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.12928/jafost.v6i3.12856.

- M. W. Ahmed, M. A. Haque, M. Mohibbullah, M. S. I. Khan, M. A. Islam, M. H. T. Mondal, and R. Ahmmed, “A review on active packaging for quality and safety of foods: Current trends, applications, prospects and challenges,” Food Packag. Shelf Life, vol. 33, p. 100913, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fpsl.2022.100913.

- W. Gunawan, R. E. Putra, P. Pujo, F. I. W. Rohmat, D. S. Hanifah, F. Awaliyah, R. D. Anggraeni, and N. Nuradzkia, “Determination of Potential in Pratama Taro (Colocasia esculenta (L). Schott var. Pratama) in Sumedang District, Bandung Regency, Indonesia,” J. Agri-Food Sci. Technol., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 11–21, 2025, https://doi.org/10.12928/jafost.v6i1.12592.

- A. K. Kimu, “A Comprehensive Review of Harnessing Bioinformatics in Biochemistry: A New Era of Data-Driven Discoveries and Applications,” Control Syst. Optim. Lett., vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 117–123, 2025, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.59247/csol.v3i1.168.

- E. Ojogbo, E. O. Ogunsona, and T. H. Mekonnen, “Chemical and physical modifications of starch for renewable polymeric materials,” Mater. Today Sustain., vol. 7–8, p. 100028, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtsust.2019.100028.

- M. N. Azkia and S. B. Wahjuningsih, “Sensory Characteristics of Mocaf-Substituted Noodles Enriched with Latoh (Caulerpa lentillifera),” J. Agri-food Sci. Technol., vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 141–151, 2025, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.12928/jafost.v6i3.14145.

- A. Surendren, A. K. Mohanty, Q. Liu, and M. Misra, “A review of biodegradable thermoplastic starches, their blends and composites: recent developments and opportunities for single-use plastic packaging alternatives,” Green Chem., vol. 24, no. 22, pp. 8606–8636, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1039/D2GC02169B.

- B. Khan, M. Bilal Khan Niazi, G. Samin, and Z. Jahan, “Thermoplastic Starch: A Possible Biodegradable Food Packaging Material—A Review,” J. Food Process Eng., vol. 40, no. 3, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1111/jfpe.12447.

- R. F. Santana, I. de C. B. Muniz, C. M. G. Lima, C. M. Veloso, F. G. Santos, and R. C. F. Bonomo, “Starch-based bioplastics and natural antimicrobials: a sustainable alternative for active packaging,” Food Biosci., vol. 74, p. 107786, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2025.107786.

- T. Jiang, Q. Duan, J. Zhu, H. Liu, and L. Yu, “Starch-based biodegradable materials: Challenges and opportunities,” Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res., vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 8–18, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aiepr.2019.11.003.

- L. M. Mena-Chacon et al., “Lemon verbena (Aloysia citriodora) essential oil: Physicochemical characterization, microencapsulation, and application in starch-based bioplastics,” Appl. Food Res., vol. 5, no. 2, p. 101530, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afres.2025.101530.

- A. O. Ashogbon and E. T. Akintayo, “Recent trend in the physical and chemical modification of starches from different botanical sources: A review,” Starch - Stärke, vol. 66, no. 1–2, pp. 41–57, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1002/star.201300106.

- D. Xie, J. Li, C. Zhang, S. Yang, A. Yang, S. Song, and Y. Song, “Design of heat-sealing starch-based bioplastics reinforced with different modified starches and TEMPO-CNF,” Ind. Crops Prod., vol. 232, p. 121303, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2025.121303.

- S. M. Amaraweera et al., “Development of Starch-Based Materials Using Current Modification Techniques and Their Applications: A Review,” Molecules, vol. 26, no. 22, p. 6880, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26226880.

- E. B. M. Viana, N. L. Oliveira, J. S. Ribeiro, M. F. Almeida, C. C. E. Souza, J. V. Resende, L. S. Santos, and C. M. Veloso, “Development of starch-based bioplastics of green plantain banana (Musa paradisiaca L.) modified with heat-moisture treatment (HMT),” Food Packag. Shelf Life, vol. 31, p. 100776, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fpsl.2021.100776.

- A. Dodero, A. Escher, S. Bertucci, M. Castellano, and P. Lova, “Intelligent Packaging for Real-Time Monitoring of Food-Quality: Current and Future Developments,” Appl. Sci., vol. 11, no. 8, p. 3532, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/app11083532.

- M. S. Khatun, “Antioxidant Peptides from Proteins: Separation, Identification, Mechanisms, and Applications in Food Systems,” Control Syst. Optim. Lett., vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 221–227, 2025, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.59247/csol.v3i2.192.

- S. Punia, “Barley starch modifications: Physical, chemical and enzymatic - A review,” Int. J. Biol. Macromol., vol. 144, pp. 578–585, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.12.088.

- H. Nawaz, R. Waheed, M. Nawaz, and D. Shahwar, “Physical and Chemical Modifications in Starch Structure and Reactivity,” in Chemical Properties of Starch, IntechOpen, 2020. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.88870.

- E. S. da Cruz, E. da C. Nunes, M. J. U. Toro, and R. da S. Pena, “The isolation method and oxidation modify the physicochemical and technological properties of non-conventional Calathea allouia starch,” LWT, vol. 223, p. 117813, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2025.117813.

- S. Srinivasan, C. Ge, C. L. Lewis, S. S. Begum, A. B. Samui, and H. F. Noyes, “Effect of chemical modification of corn starch for the development of films for packaging applications: Impact of glutaraldehyde and organically modified montmorillonite incorporation,” Carbohydr. Polym., vol. 367, p. 124019, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2025.124019.

- L. A. Bello‐Perez, P. C. Flores‐Silva, E. Agama‐Acevedo, and J. Tovar, “Starch digestibility: past, present, and future,” J. Sci. Food Agric., vol. 100, no. 14, pp. 5009–5016, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.8955.

- S. U. Kadam, B. K. Tiwari, and C. P. O’Donnell, “Improved thermal processing for food texture modification,” in Modifying Food Texture, Elsevier, 2015, pp. 115–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-78242-333-1.00006-1.

- B. Olawoye, O. S. Jolayemi, T. Y. Akinyemi, M. Nwaogu, T. D. Oluwajuyitan, O. O. Popoola-Akinola, O. F. Fagbohun, and C. T. Akanbi, “Modification of Starch,” in Starch: Advances in Modifications, Technologies and Applications, pp. 11–54, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-35843-2_2.

- C. Sudheesh, L. Varsha, K. V. Sunooj, and S. Pillai, “Influence of crystalline properties on starch functionalization from the perspective of various physical modifications: A review,” Int. J. Biol. Macromol., vol. 280, p. 136059, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.136059.

- Z. Ma, X. Hu, and J. I. Boye, “Research advances on the formation mechanism of resistant starch type III: A review,” Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr., vol. 60, no. 2, pp. 276–297, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2018.1523785.

- N. Bhati et al., “Eco‐Friendly Enzymatic Starch Modification: Precision Strategies for Tailored Industrial and Biomedical Functionalities,” Starch - Stärke, vol. 77, no. 9, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1002/star.70087.

- M. A. Zailani, H. Kamilah, A. Husaini, A. Z. R. Awang Seruji, and S. R. Sarbini, “Starch Modifications via Physical Treatments and the Potential in Improving Resistant Starch Content,” Starch - Stärke, vol. 75, no. 1–2, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1002/star.202200146.

- P. Ge, Y. Tian, H. Yan, Q. Li, T. Yao, J. Yao, L. Xiao, M. Zhu, and Y. Han, “Functional Modification and Applications of Rice Starch Emulsion Systems Based on Interfacial Engineering,” Foods, vol. 14, no. 13, p. 2228, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14132228.

- E. M. Gonçalves, M. Silva, L. Andrade, and J. Pinheiro, “From Fields to Films: Exploring Starch from Agriculture Raw Materials for Biopolymers in Sustainable Food Packaging,” Agriculture, vol. 14, no. 3, p. 453, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14030453.

- I. Kusuma, S. N. Rahmadhia, and A. Ma’arif, “Exploring the Role of Biotechnology and Biodiversity in Achieving Sustainable and Nutritional Food Systems,” J. Sci. Agrotechnology, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 21–29, 2024, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.21107/jsa.v2i1.20.

- M. Haroon et al., “Chemical modification of starch and its application as an adsorbent material,” RSC Adv., vol. 6, no. 82, pp. 78264–78285, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1039/C6RA16795K.

- E. Subroto, Y. Cahyana, R. Indiarto, and T. A. Rahmah, “Modification of Starches and Flours by Acetylation and Its Dual Modifications: A Review of Impact on Physicochemical Properties and Their Applications,” Polymers (Basel)., vol. 15, no. 14, p. 2990, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15142990.

- I. Choi, W. Hong, J.-S. Lee, and J. Han, “Influence of acetylation and chemical interaction on edible film properties and different processing methods for food application,” Food Chem., vol. 426, p. 136555, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.136555.

- S. Dimri, Aditi, Y. Bist, and S. Singh, “Oxidation of Starch,” in Starch: Advances in Modifications, Technologies and Applications, pp. 55–82, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-35843-2_3.

- C. Beveridge and A. Sabiston, “Methods and benefits of crosslinking polyolefins for industrial applications,” Mater. Des., vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 263–268, 1987, https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-3069(87)90003-3.

- R. . Tharanathan, “Biodegradable films and composite coatings: past, present and future,” Trends Food Sci. Technol., vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 71–78, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-2244(02)00280-7.

- J. Meimoun, V. Wiatz, R. Saint‐Loup, J. Parcq, A. Favrelle, F. Bonnet, and P. Zinck, “Modification of starch by graft copolymerization,” Starch - Stärke, vol. 70, no. 1–2, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1002/star.201600351.

- M. Gosecka and T. Basinska, “Hydrophilic polymers grafted surfaces: preparation, characterization, and biomedical applications. Achievements and challenges,” Polym. Adv. Technol., vol. 26, no. 7, pp. 696–706, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1002/pat.3554.

- L. M. Fonseca, S. L. M. El Halal, A. R. G. Dias, and E. da R. Zavareze, “Physical modification of starch by heat-moisture treatment and annealing and their applications: A review,” Carbohydr. Polym., vol. 274, p. 118665, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118665.

- Y. Cahyana et al., “Properties Comparison of Oxidized and Heat Moisture Treated (HMT) Starch-Based Biodegradable Films,” Polymers (Basel)., vol. 15, no. 9, p. 2046, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15092046.

- E. da R. Zavareze and A. R. G. Dias, “Impact of heat-moisture treatment and annealing in starches: A review,” Carbohydr. Polym., vol. 83, no. 2, pp. 317–328, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.08.064.

- T. Yao, Z. Sui, and S. Janaswamy, “Annealing,” in Physical Modifications of Starch, pp. 73–89, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-5390-5_5.

- S. Biswas and T. U. Rashid, “Effect of ultrasound on the physical properties and processing of major biopolymers—a review,” Soft Matter, vol. 18, no. 44, pp. 8367–8383, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1039/D2SM01339H.

- A. J. Vela, M. Villanueva, and F. Ronda, “Ultrasonication: An Efficient Alternative for the Physical Modification of Starches, Flours and Grains,” Foods, vol. 13, no. 15, p. 2325, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13152325.

- M. J. E. . van der Maarel, B. van der Veen, J. C. Uitdehaag, H. Leemhuis, and L. Dijkhuizen, “Properties and applications of starch-converting enzymes of the α-amylase family,” J. Biotechnol., vol. 94, no. 2, pp. 137–155, 2002, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1656(01)00407-2.

- S. O. Hashim, “Starch-Modifying Enzymes,” pp. 221–244, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1007/10_2019_91.

- P. Zhang, F. Sun, X. Cheng, X. Li, H. Mu, S. Wang, H. Geng, and J. Duan, “Preparation and biological activities of an extracellular polysaccharide from Rhodopseudomonas palustris,” Int. J. Biol. Macromol., vol. 131, pp. 933–940, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.03.139.

- E. M. Milczek, “Commercial Applications for Enzyme-Mediated Protein Conjugation: New Developments in Enzymatic Processes to Deliver Functionalized Proteins on the Commercial Scale,” Chem. Rev., vol. 118, no. 1, pp. 119–141, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00832.

- M. C. Operti, A. Bernhardt, V. Sincari, E. Jager, S. Grimm, A. Engel, M. Hruby, C. G. Figdor, and O. Tagit, “Industrial Scale Manufacturing and Downstream Processing of PLGA-Based Nanomedicines Suitable for Fully Continuous Operation,” Pharmaceutics, vol. 14, no. 2, p. 276, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics14020276.

- E. Basiak, A. Lenart, and F. Debeaufort, “Effect of starch type on the physico-chemical properties of edible films,” Int. J. Biol. Macromol., vol. 98, pp. 348–356, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.01.122.

- P. Song and H. Wang, “High‐Performance Polymeric Materials through Hydrogen‐Bond Cross‐Linking,” Adv. Mater., vol. 32, no. 18, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201901244.

- S. N. Rahmadhia, A. A. Sidqi, and Y. A. Saputra, “Physical Properties of Tapioca Starch-based Film Indicators with Anthocyanin Extract from Purple Sweet Potato (Ipomea batatas L.) and Response to pH Changes,” Sains Malaysiana, vol. 52, no. 6, pp. 1685–1697, 2023, https://doi.org/10.17576/jsm-2023-5206-06.

- Z. Eslami, S. Elkoun, M. Robert, and K. Adjallé, “A Review of the Effect of Plasticizers on the Physical and Mechanical Properties of Alginate-Based Films,” Molecules, vol. 28, no. 18, p. 6637, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28186637.

- J. Li, Z. Li, Y. Yan, D. Shao, Y. Guo, and R. Lin, “Study on the structure–property relationship of starch/PLA composite films modified by the synergistic effect of aromatic rings and aliphatic chains,” Polym. Degrad. Stab., vol. 241, p. 111567, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2025.111567.

- A. A. Al-Hassan and M. H. Norziah, “Starch–gelatin edible films: Water vapor permeability and mechanical properties as affected by plasticizers,” Food Hydrocoll., vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 108–117, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2011.04.015.

- K. Czerwiński, T. Rydzkowski, J. Wróblewska-Krepsztul, and V. K. Thakur, “Towards Impact of Modified Atmosphere Packaging (MAP) on Shelf-Life of Polymer-Film-Packed Food Products: Challenges and Sustainable Developments,” Coatings, vol. 11, no. 12, p. 1504, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings11121504.

- H. Onyeaka, K. Obileke, G. Makaka, and N. Nwokolo, “Current Research and Applications of Starch-Based Biodegradable Films for Food Packaging,” Polymers (Basel)., vol. 14, no. 6, p. 1126, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14061126.

- M. Zabihzadeh Khajavi, A. Ebrahimi, M. Yousefi, S. Ahmadi, M. Farhoodi, A. Mirza Alizadeh, and M. Taslikh, “Strategies for Producing Improved Oxygen Barrier Materials Appropriate for the Food Packaging Sector,” Food Eng. Rev., vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 346–363, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12393-020-09235-y.

- F. Versino, O. V. Lopez, M. A. Garcia, and N. E. Zaritzky, “Starch‐based films and food coatings: An overview,” Starch - Stärke, vol. 68, no. 11–12, pp. 1026–1037, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1002/star.201600095.

- S. Singha and M. S. Hedenqvist, “A Review on Barrier Properties of Poly(Lactic Acid)/Clay Nanocomposites,” Polymers (Basel)., vol. 12, no. 5, p. 1095, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12051095.

- M. L. Sanyang, S. M. Sapuan, M. Jawaid, M. R. Ishak, and J. Sahari, “Effect of plasticizer type and concentration on physical properties of biodegradable films based on sugar palm (arenga pinnata) starch for food packaging,” J. Food Sci. Technol., vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 326–336, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-015-2009-7.

- T. R. Arruda et al., “An Overview of Starch-Based Materials for Sustainable Food Packaging: Recent Advances, Limitations, and Perspectives,” Macromol, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 19, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/macromol5020019.

- Y. Liu, L. Yang, C. Ma, and Y. Zhang, “Thermal Behavior of Sweet Potato Starch by Non-Isothermal Thermogravimetric Analysis,” Materials (Basel)., vol. 12, no. 5, p. 699, 2019, https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12050699.

- X. Liu, Y. Wang, L. Yu, Z. Tong, L. Chen, H. Liu, and X. Li, “Thermal degradation and stability of starch under different processing conditions,” Starch - Stärke, vol. 65, no. 1–2, pp. 48–60, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1002/star.201200198.

- M. O. Tuhin, N. Rahman, M. E. Haque, R. A. Khan, N. C. Dafader, R. Islam, M. Nurnabi, and W. Tonny, “Modification of mechanical and thermal property of chitosan–starch blend films,” Radiat. Phys. Chem., vol. 81, no. 10, pp. 1659–1668, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radphyschem.2012.04.015.

- Y. Garavand, A. Taheri-Garavand, F. Garavand, F. Shahbazi, D. Khodaei, and I. Cacciotti, “Starch-Polyvinyl Alcohol-Based Films Reinforced with Chitosan Nanoparticles: Physical, Mechanical, Structural, Thermal and Antimicrobial Properties,” Appl. Sci., vol. 12, no. 3, p. 1111, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031111.

- D. Phothisarattana and N. Harnkarnsujarit, “Migration, aggregations and thermal degradation behaviors of TiO2 and ZnO incorporated PBAT/TPS nanocomposite blown films,” Food Packag. Shelf Life, vol. 33, p. 100901, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fpsl.2022.100901.

- J. M. Fernández, C. Plaza, A. Polo, and A. F. Plante, “Use of thermal analysis techniques (TG–DSC) for the characterization of diverse organic municipal waste streams to predict biological stability prior to land application,” Waste Manag., vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 158–164, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2011.08.011.

- A. Jiménez, M. J. Fabra, P. Talens, and A. Chiralt, “Edible and biodegradable starch films: A review,” Food Bioprocess Technol., vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 2058–2076, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11947-012-0835-4.

- S. Mehboob, T. M. Ali, M. Sheikh, and A. Hasnain, “Effects of cross linking and/or acetylation on sorghum starch and film characteristics,” Int. J. Biol. Macromol., vol. 155, pp. 786–794, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.03.144.

- M. Shahbazi, G. Rajabzadeh, A. Rafe, R. Ettelaie, and S. J. Ahmadi, “Physico-mechanical and structural characteristics of blend film of poly (vinyl alcohol) with biodegradable polymers as affected by disorder-to-order conformational transition,” Food Hydrocoll., vol. 71, pp. 259–269, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.04.017.

- K. Vaezi, G. Asadpour, and H. Sharifi, “Effect of ZnO nanoparticles on the mechanical, barrier and optical properties of thermoplastic cationic starch/montmorillonite biodegradable films,” Int. J. Biol. Macromol., vol. 124, pp. 519–529, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.142.

- A. F. Routh, “Drying of thin colloidal films,” Reports Prog. Phys., vol. 76, no. 4, p. 046603, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1088/0034-4885/76/4/046603.

- C. I. La Fuente Arias, M. T. K. Kubo, C. C. Tadini, and P. E. D. Augusto, “Bio-based multilayer films: A review of the principal methods of production and challenges,” Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr., vol. 63, no. 14, pp. 2260–2276, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2021.1973955.

- L. de S. Falcão, D. B. Coelho, P. C. Veggi, P. H. Campelo, P. M. Albuquerque, and M. A. de Moraes, “Starch as a Matrix for Incorporation and Release of Bioactive Compounds: Fundamentals and Applications,” Polymers (Basel)., vol. 14, no. 12, p. 2361, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14122361.

- F. A. Triana, M. Devi, and S. Soekopitojo, “The Effect of Breadfruit Leaves (Artocarpus altilis) Addition to Antioxidant Content and Organoleptic Properties of Ginger Wedang,” J. Agri-Food Sci. Technol., vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 81–87, 2022, https://doi.org/10.12928/jafost.v2i1.4314.

- M. Hadi, A. Permadi, T. E. Suharto, M. W. Putri, H. A. P. Gulo, N. O. Maema, H. Halimathusyakhdyah, and A. Lupi, “Phytochemical Test of Sacha Inchi Oil from Central Java,” J. Agri-Food Sci. Technol., vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 168–177, 2025, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.12928/jafost.v6i3.12885.

- R. Syafiq, S. M. Sapuan, M. Y. M. Zuhri, R. A. Ilyas, A. Nazrin, S. F. K. Sherwani, and A. Khalina, “Antimicrobial Activities of Starch-Based Biopolymers and Biocomposites Incorporated with Plant Essential Oils: A Review,” Polymers (Basel)., vol. 12, no. 10, p. 2403, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12102403.

- M. S. Khatun, “Challenges and Prospects of Bioactive Peptides Produced from Plants as Sustainable Source - A Case Study,” J. Sci. Agrotechnology, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 1–9, 2025, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.21107/jsa.v3i1.23.

- S. O. Olunusi, N. H. Ramli, F. Adam, and S. N. Rahmadhia, “Stability, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of ginger essential oil nanoemulsion: Impact of droplet size and concentration with molecular dynamics insights into zingiberene bioactivity,” Food Biosci., vol. 71, p. 107174, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2025.107174.

- L. Diniz do Nascimento et al., “Bioactive Natural Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Essential Oils from Spice Plants: New Findings and Potential Applications,” Biomolecules, vol. 10, no. 7, p. 988, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10070988.

- M. S. Khatun and A. Jahan, “Bioinformatics Analysis of Toxicity and Functional Properties of Plant-Derived Bioactive Proteins,” Control Syst. Optim. Lett., vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 241–247, 2024, https://doi.org/10.59247/csol.v2i2.112.

- F. C. Agustia, R. Salma, S. A. Hamidah, K. R. Dewi, and S. Sanayei, “Total Phenolic Content and Hedonic Quality of Germinated Jack Bean Tempeh at Different Fermentation Times and Packaging Types,” J. Agri-Food Sci. Technol., vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 73–86, 2025, https://doi.org/10.12928/jafost.v6i2.12698.

- S. N. Rahmadhia and T. Juwitaningtyas, “Physicochemical Properties of Klutuk banana Leaves (Musa balbisiana Colla) Susu and Wulung Cultivars with its Potential as Antioxidant,” J. Agri-Food Sci. Technol., vol. 1, no. 1, p. 18, 2020, https://doi.org/10.12928/jafost.v1i1.1942.

- J. R. Rendón-Villalobos, J. Solorza-Feria, F. Rodríguez-González, and E. Flores-Huicochea, “Barrier properties improvement using additives,” in Food Packaging, Elsevier, 2017, pp. 465–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804302-8.00014-5.

- W. Weisany, S. Yousefi, N. A. Tahir, N. Golestanehzadeh, D. J. McClements, B. Adhikari, and M. Ghasemlou, “Targeted delivery and controlled released of essential oils using nanoencapsulation: A review,” Adv. Colloid Interface Sci., vol. 303, p. 102655, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cis.2022.102655.

- N. P. Mbonambi, J. O. Adeyemi, F. Seke, and O. A. Fawole, “Fabrication and Application of Bio-Based Natural Polymer Coating/Film for Food Preservation: A Review,” Processes, vol. 13, no. 8, p. 2436, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13082436.

- A. Belasli, L. Aguerri, L. Ait Ouahioune, R. Becerril, M. Quintero, E. Canellas, A. Ariño, D. Djenane, C. Nerín, and F. Silva, “Microbial safety improvement of date fruits using a Thymus numidicus essential oil-based active packaging,” Food Packag. Shelf Life, vol. 52, p. 101673, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fpsl.2025.101673.

- A. L. G. Rosas, N. R. Kleinübing, C. K. Bierhals, B. da Fonseca Antunes, A. F. Carloto, D. R. Silveira, W. P. da Silva, E. da Rosa Zavareze, G. V. Lopes, and A. D. Meinhart, “Cryogels based on Brazilian purple yam (Dioscorea trifida L.f.) starch: An antimicrobial active packaging approach for microbial and moisture control in fresh cheese,” Int. J. Biol. Macromol., p. 149281, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.149281.