ISSN: 2685-9572 Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro

Vol. 7, No. 4, December 2025, pp. 931-943

Banana Blossom as a Novel Ingredient in The Zero Waste Strategy: Application in Flakes

Safinta Nurindra Rahmadhia 1, Meta Sari 1, Maulidya Eka Wahyudi 1, Ibdal 1, Aprilia Fitriani 1,

Ali Jebreen 2

1 Food Technology Department, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Indonesia

2 Department of Medical Therapeutic Nutrition, Palestine Ahliya University, Palestine

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 17 September 2025 Revised 28 October 2025 Accepted 02 December 2025 |

|

Banana bud is an underutilized byproduct of the banana plant. Banana bud is rich in fiber and macronutrients that promote health. The potential of banana buds can be optimized by transforming them into convenient, ready-to-eat food products. This study contributed to facilitating the conversion of agricultural waste into nutrient-dense functional foods. This investigation will involve the preparation of flakes using banana bud flour and arrowroot flour as substitutes for wheat flour. Each mixture incorporated banana bud and arrowroot flour at concentrations of 5%, 10%, and 15%. Additionally, the flakes will undergo assessment of their chemical, physical, and sensory characteristics. The incorporation of banana bud and arrowroot flour into the flakes resulted in a considerable increase in total protein and crude fiber values compared to the control sample. The hardness and crunchiness of the flakes varied considerably, although the water absorption capacity rose markedly. The incorporation of banana bud flour resulted in the flakes acquiring a reddish hue. The outcomes of the descriptive sensory evaluation yielded an assessment of color, odor, texture, flavor, aftertaste, and texture after rehydration conducted by the panellists. The study’s results indicate that banana plant waste can be utilized to produce nutrient-dense food products favored by panellists. |

Keywords: Arrowroot; Banana bud; Flakes; Food processing; Physicochemical |

Corresponding Author: Aprilia Fitriani, Food Technology Department, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Jl. Ahmad Yani, Tamanan, Banguntapan, Bantul, Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta, Indonesia Email: aprilia.fitriani@tp.uad.ac.id |

|

This work is open access under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

|

Document Citation: S. N. Rahmadhia, M. Sari, M. E. Wahyudi, Ibdal, A. Fitriani, and A. Jebreen, “Banana Blossom as a Novel Ingredient in The Zero Waste Strategy: Application in Flakes,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 931-943, 2025, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v7i4.14976. |

- INTRODUCTION

Bananas are a popular and widely consumed fruit. During the banana plant's growth process, the final stage produces nutrient-rich banana blossoms [1], [2]. In banana horticulture, the banana blossom is removed and discarded once the bunch has formed and its hands begin to ascend. Banana blossoms, also known as banana flower, banana inflorescence, banana heart, banana peduncle, or banana buds, are the consumable byproduct of banana cultivation, which have significant nutritional content [3], [4], [5], [6]. They comprise several bioactive substances and serve as a substantial source of crude fiber (5–6%), which aids in managing diabetes, facilitates weight loss, and promotes gastrointestinal health [7], [8]. The various benefits of banana blossom are explained in Table 1.

Table 1. Function of banana blossom.

Function | References |

Anti-diabetes, anticancer, anti-inflammatory | [3], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12] |

Antioxidant | [10], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19] |

Inhibiting the non-enzymatic glycation of proteins | [20], [21], [22] |

Therapeutic potential | [23], [24] |

Source of fiber | [13], [25], [26] |

Development in the health sector | [27], [28] |

In Indonesia, banana buds are primarily consumed as vegetables. Given their rich nutritional content, they should be processed into nutrient-rich foods that a wide range of people can consume. In various studies, banana blossom has been developed into functional products as described in Table 2. Convenient foods that are flavorful and nutritionally beneficial are consistently preferred by individuals of all ages [29], [30], [31], [32]. Baking products enjoy widespread popularity globally. The bakery food industry is rapidly becoming one of the main sectors in the global food market. The demand for bakery items (bread, cake, biscuits, cereal, flakes, etc.) is rising daily at an annual rate of 10.07% [1], [33], [34]. In various studies on banana blossoms, there has been no research that processes banana blossoms into ready-to-eat products such as flakes.

Table 2. Banana blossom application.

Flakes are a ready-to-eat meal frequently eaten for breakfast because they can be consumed directly after purchasing or need little preparation before consumption [35], [41], [42]. Commercially produced flakes are often composed of wheat flour and corn flour, commonly referred to as corn flakes. The incorporation of additional functional elements into flake production leads to substantial alterations in both the quantitative and qualitative characteristics of the final flake products, which directly affect functional attributes such as water retention, stability, and texturization [43], [44]. It is advantageous to partially or completely substitute wheat flour to enhance the nutritional value of the product. Substituting wheat flour with alternative flours has been claimed to enhance the functional and nutritional attributes of baked products [45], [46], [47], [48]. The incorporation of banana bud flour into flake manufacture is a nutrient-dense culinary innovation and a viable alternative for the utilization of agricultural waste. To enhance the texture and nutritional quality of flakes, tuber flour may be used as a substitute for wheat flour [49].

Arrowroot is an enormous perennial herb found in tropical woods, characterized by its high starch content and significant commercial value [50], [51]. Arrowroot flour serves as a carbohydrate source and possesses a low glycemic index, making it suitable for intake by specific individuals [52], [53]. The starch level in the rhizome of arrowroot fluctuates with the plant's age, averaging around 20%, of which approximately 20–30% consists of amylose [54], [55]. In numerous food manufacturing applications, tuber flour is commonly utilized to substitute wheat flour [56]. Arrowroot has been extensively utilized as an ingredient in baked goods, ice cream, gelatin, and infant nutrition [57], [58]. Nevertheless, its capacity for generating flakes has not been extensively examined. Due to its good digestion, arrowroot is useful for infants, the elderly, people with digestive difficulties, and those with celiac disease [55].

The production of flakes utilizing banana bud flour and arrowroot flour represents a significant advancement in high-nutrient food innovation. This research contributes to the utilization of agricultural waste to generate nutrient-dense functional flakes. Additionally, the flakes will undergo analysis of their physical and chemical properties to ascertain their nutritional composition. A sensory investigation will be performed to determine consumer preference for the flakes. Fruit residues serve as exceptional functional additives, enhancing or moderating organoleptic features such as odor, color, nutritional parameters, taste, and texture. Fruits provide nutritional advantages to the consumer while enhancing sensory attributes [59], [60].

- METHODS

- Flakes Production

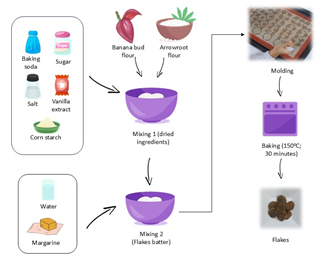

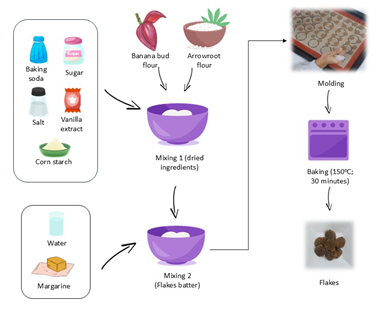

The method for producing flakes begins with the flouring of kepok banana buds (KBB). The crushed KBB are immersed in 0.2% citric acid and thereafter steamed for 6 minutes at 70 °C. The KBB are subsequently dehydrated in a cabinet drier at 60 °C for 6 hours. The flour is processed using a grinder and subsequently sifted through an 80-mesh sieve. The KBB flour is afterwards combined with arrowroot flour and wheat flour in certain proportions. Additional substances utilized in the preparation of flakes include water (100 ml), maize starch (8% w/v), sugar (14.4% w/v), salt (0.58% w/v), baking soda (0.24% w/v), vanilla powder (0.24% w/v), and margarine (2.4% w/v) [61], [62]. Table 3 demonstrates the compositional comparison of wheat, arrowroot, and banana bud flour, while Figure 1 presents the flow of flakes production.

Table 3. The comparison of banana bud, arrowroot and wheat flour.

Materials | F0 | F1 | F2 | F3 |

Wheat flour (% w/v) | 40 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

Arrowroot flour (% w/v) | 0 | 15 | 10 | 5 |

KBB flour (% w/v) | 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 |

Figure 1. Diagram of the flakes production.

- Total Protein Analysis

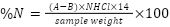

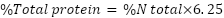

A 100 mg sample was utilized for total protein measurement in KBB flakes. The protein concentration in the sample was assessed by digestion, distillation, and titration methods [63], [64]. The determination of protein content in the sample was predicated on (1) and (2).

|

| (1) |

|

| (2) |

Where  is the sample titration volume (ml), and

is the sample titration volume (ml), and  is the blank titration volume (ml).

is the blank titration volume (ml).

- Crude Fiber Analysis

The crude fiber analysis method involves the sequential boiling of a sample in acid, followed by alkali to eliminate non-fiber constituents. After digestion, the residual fiber is filtered, desiccated, and weighed, after which the residue is burnt in a muffle furnace. The final computation involves subtracting the ash weight from the dry weight of the fiber residual and dividing the result by the original sample weight, reported as a percentage [65], [66].

- Texture Analysis

Texture analysis was performed using a texture analyzer. Hardness and crispness values were obtained for each sample to determine the physical quality of the sample [67], [68].

- Water Absorption Capacity Analysis

The gravimetric method has been used for water absorption analysis by submerging the sample in heated water. The sample was subsequently taken out, drained, and weighed to ascertain its water absorption value. The water absorption value was determined by dividing the mass before and after immersion by the original mass of the sample [69].

- Optical Properties Analysis

Color analysis of flakes was performed using a chromameter. The color parameters determined were lightness (L*), appearance (a*), and blueness (b*) [70], [71].

- Sensory Evaluation Analysis

The sensory evaluation of flakes is conducted to assess consumer approval of the product by human senses or sensors [72], [73]. In food product research, the sensory characteristics of a product ultimately determine its acceptance or rejection [74], [75]. This study's organoleptic test involved 30 untrained panelists aged 20 to 23 years. Researchers disseminated a questionnaire concerning flake products via form. The established list of inquiries corresponded to the hedonic assessment (color, odor, texture, taste, aftertaste, and rehydration texture, along with overall evaluation) and descriptive analyses (color, aroma, texture, taste, aftertaste, and rehydration texture) [76], [77], [78]. The evaluation scale in the hedonic test of arrowroot flour flakes with the incorporation of KBB flour comprised (1) dislike, (2) slightly like, (3) like, and (4) very much like. The evaluative scale for flakes is presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Descriptive evaluation scale for KBB flakes.

Scale | Color | Odor | Texture | Taste | Aftertaste | Texture after rehydration |

1 | Brownish white | No arrowroot flour odor and no banana bud odor | Not crispy | Bitter | Bitter | Very soft |

2 | Brown | It has a slight odor of arrowroot flour and not banana bud | Slight crispy | Slight bitter | Slight bitter | Soft |

3 | Dark brown | No odor of arrowroot flour and has odor of banana bud | Crispy | Sweet | Sweet | Crispy |

4 | Blackish brown | Aromatic of arrowroot flour and banana bud | Very crispy | Very sweet | Very sweet | Very crispy |

- RESULT AND DISCUSSION

- Total Protein of KBB Flakes

The protein in our diet serves as an energy source and fulfils additional functions, such as facilitating the transport of biochemicals across cellular membranes and catalyzing enzymatic activity. Furthermore, adequate protein from food consumption is a crucial nutritional element for the prevention of illnesses like sarcopenia in an ageing global demographic [79], [80].

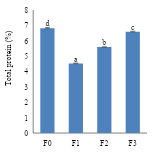

Figure 2 indicates that the total protein content of KBB flakes increased significantly with the addition of banana bud flour. Flakes made from wheat flour had the highest protein content compared to the treated samples. This was due to differences in protein content in the raw materials. Arrowroot only has a protein content of 0.72% [55], while banana blossom has a protein content of 1.62–2.07% [37]. In research, banana blossom flour utilized for cake production showed a crude protein level ranging from 14.20% to 15.18%. Acid pretreatment of the banana blossom enhanced protein output [1], [81].

Figure 2. Total protein content of KBB flakes. Different notations indicate a significant difference at α=5%.

- Crude Fiber of KBB Flakes

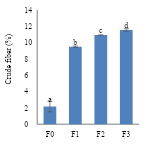

A notable rise in crude fiber content was seen in flakes enhanced with banana bud and arrowroot flour (Figure 3). Wheat flour flakes comprise merely 2.17% crude fiber, whereas KBB flakes possess 9.5–11.54% crude fiber. Banana bud is a fiber-rich byproduct, comprising around 5–6%, whereas arrowroot contains 1% [7], [8], [55]. Cakes prepared with banana blossom possess a greater crude fiber content compared to those produced with wheat flour [1]. This indicates that banana blossom may serve as a high-fiber food component. Dietary fiber is sourced from fruits, nuts, and vegetables. Vegetables with high fiber content, such as banana blossom, facilitate the digestive system, regulate body weight, and bind blood lipids and cholesterol [82], [83], [84].

Figure 3. Crude fiber content of KBB flakes. Different notations indicate a significant difference at α=5%.

- Texture of KBB Flakes

The textural properties of the flakes were examined for their hardness and crunchiness [85]. The values of hardness and crunchiness vary due to discrepancies in flake morphology (Table 5). Irregularities in flake morphology influence the overall texture of the flakes. An elevated hardness value signifies a more rigid and robust flake texture. A greater crunchiness score signifies a more rigid flake [82], [86], [87].

Table 5. Texture value of KBB flakes.

Sampel | Hardness (N) | Crunchiness (Nmm) |

F0 | 2.90 ± 0.34b | 7.35 ± 2.77b |

F1 | 3.75 ± 0.01a | 15.66 ± 2.21b |

F2 | 4.03 ± 0.60a | 3.67 ± 0.08a |

F3 | 2.66 ± 0.21ab | 13.27 ± 0.93b |

Note: Different notations indicate a significant difference at α=5%.

Hardness denotes the strength or force necessary to bite and compress food [88]. It is a crucial element in food texture analysis, frequently evaluated by consumers to determine the quality and acceptance of a product [89], [90]. The hardness of bakery products is a significant concern, as the breaking strength of food items is a primary factor influencing consumer approval [91], [92]. Various elements influence the hardness of a baked product; however, in flakes, hardness is frequently associated with moisture content [93]. The structure and configuration of amylose and amylopectin influence the size and crystallinity of starch granules, impact water absorption, and alter the texture and crispness of cookies. Amylose, owing to its linear and little-branched structure, creates rigid helical complexes, yielding tougher and crispier cookies after baking, which attracts consumers who want a crunchier feel [94], [95].

- Water Absorption Capacity of KBB Flakes

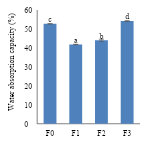

Water absorption capacity refers to a substance's ability to absorb and retain water, typically expressed as the ratio of absorbed water to the weight of the dry material [96]. The capacity for water absorption is influenced by several elements, including the material's composition—specifically its protein, starch, and fiber content—as well as its physical characteristics, such as moisture content, particle size, and porosity [97], [98]. Flakes with 15% banana bud flour added have the highest water absorption capacity value compared to flakes with 5% and 10% (Figure 4). A greater fiber content correlates with an increased capacity for water absorption [99], [100]. Fiber possesses a significant water absorption capacity owing to its complex structure and the abundance of hydroxyl groups capable of binding water molecules [101], [102].

Figure 4. Water absorption capacity of KBB flakes. Different notations indicate a significant difference at α=5%.

- Optical Properties of KBB Flakes

Color significantly impacted consumers' food selections and directly affected product marketing. The hue of food products was determined by the materials incorporated in their formulations [103], [104]. The optical characteristics of flakes are denoted by color variations, typified by alterations in L*, a*, and b* values (Figure 5) [105]. The L* value denotes the brightness of the flakes; thus, an increase in banana bud addition resulted in a considerable decrease in flake brightness (Figure 5). This signifies that the hue of the KBB flakes has deepened. Flakes without banana buds and arrowroot flour had the lightest hue. The a* value in color analysis indicates the appearance of the flakes. A positive a* value indicates a red color, while a negative value indicates a green color. Control flakes tended to have a greenish color, while flakes with banana bud flour tended to have a reddish color. A positive b* value indicated a yellow color, while a negative b* value indicated a blue color [106], [107], [108]. Control flakes had a significantly more yellow color than flakes with banana bud and arrowroot flour.

- Sensory Evaluation of KBB Flakes

Table 6 illustrates the sensory assessment of flakes using KBB flour and arrowroot flour in comparison to wheat flakes. The panellists' evaluations indicated that the flakes exhibited a markedly enhanced colour score with the increase of KBB flour incorporation. F0 exhibited a brownish-white hue, whereas F3 exhibited a blackish-brown hue.

Table 6. Sensory evaluation of KBB flakes.

Sampel | Color | Odor | Texture | Taste | Aftertaste | Texture after rehydration |

F0 | 1.00 ± 0.00a | 1.70 ± 0.89a | 3.27 ± 0.74a | 3.00 ± 0.74c | 3.07 ± 0.36d | 3.27 ± 0.64b |

F1 | 2.17 ± 0.53b | 2.93 ± 0.94b | 3.13 ± 1.01a | 2.80 ± 0.55c | 2.70 ± 0.59c | 3.23 ± 0.63ab |

F2 | 3.10 ± 0.61c | 3.07 ± 1.05b | 3.00 ± 0.95a | 2.47 ± 0.78b | 2.30 ± 0.79b | 3.20 ± 0.66ab |

F3 | 3.83 ± 0.38d | 3.22 ± 0.01b | 3.30 ± 0.65a | 2.00 ± 0.69a | 1.93 ± 0.64a | 2.90 ± 0.61a |

Note: Different notations indicate a significant difference at α=5%.

Figure 5. Optical evaluation of LBB flakes. Lightness (a), appearance (b), and brightness (c). Different notations indicate a significant difference at α=5%.

The incorporation of arrowroot flour and KBB provided the flakes with the odor of banana blossom flour and arrowroot flour. The panellists determined that the control flakes lacked the scent of both banana blossom flour and arrowroot flour. The texture of the flakes showed no significant differences between parameters. Therefore, according to the panelists, the flakes with the addition of KBB flour and arrowroot had a texture similar to wheat flour flakes.

The more KBB flour added to the flake formulation, the more bitter the flakes became. The bitterness in banana blossoms is caused by the tannins they contain. These polyphenols produce an astringent or bitter taste, similar to over-steeped tea [109]. The bitter flavour of the flakes influences the aftertaste upon consumption. F3 possesses a slightly bitter aftertaste in contrast to F0, which exhibits a pleasant aftertaste. The panellists indicated that an increased addition of KBB flour correlates with a heightened bitterness in the aftertaste.

Flakes that have been added with water or milk will produce a different texture than flakes consumed without water or milk. F3 has a softer texture after rehydration, compared to F0, which has a crispier texture. Texture after rehydration is related to water absorption capacity. The higher the water absorption capacity, the softer the texture after rehydration. However, the thickness of the sample also affects its texture after being dipped in water or milk [110], [111].

- CONCLUSIONS

Based on the research conducted, it can be concluded that the use of banana bud flour in making flakes can improve the nutritional quality of the flakes. The total protein value and fiber content of flakes with the addition of banana bud flour increased significantly compared to the control sample. In addition, changes in chemical quality also affected the physical quality of the flakes. The texture and water absorption capacity of flakes with the addition of banana bud flour were significantly different from the control sample. The use of banana bud flour produced flakes with a brownish color. Based on the panelists' assessment, KBB flakes were acceptable by the panelists in terms of color, odor, texture, taste, aftertaste, and texture after rehydration.

DECLARATION

Sustainable Development Goals

The suitable development goals can be categorized as Zero hunger (SDG 2), Good health and Well-being (SDG 3), and Responsible Consumption and Production (SDG 12).

Author Contribution

All authors contributed equally to the main contributor to this paper. All authors read and approved the final paper. Safinta Nurindra Rahmadhia: Conceptualization; Methodology; Validation; Writing - Original draft; Supervision. Meta Sari: Investigation; Formal analysis; Writing - Original draft preparation; Software. Maulidya Eka Wahyudi: Investigation; Formal analysis; Writing - Original draft preparation; Software. Aprilia Fitriani: Writing - Reviewing and Editing. Ibdal: Writing - Reviewing and Editing.

Funding

This research was funded by the Directorate General of Higher Education, Research, and Technology, Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology, Republic of Indonesia, through the Directorate of Research Technology and Community Service (DRTPM) with a fundamental research scheme (Grant Number: 109/PFR/LPPM-UAD/VI/2024).

Acknowledgement

The authors are thankful to the Directorate General of Higher Education, Research, and Technology, Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology, Republic of Indonesia, for the financial support to this research through the Directorate of Research Technology and Community Service (DRTPM) with a fundamental research scheme (Grant Number: 109/PFR/LPPM-UAD/VI/2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

[1] T. Tasnim, P. C. Das, A. A. Begum, A. H. Nupur, and M. A. R. Mazumder, “Nutritional, textural and sensory quality of plain cake enriched with rice rinsed water treated banana blossom flour,” J. Agric. Food Res., vol. 2, p. 100071, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2020.100071.

[2] N. S. Mathew and P. S. Negi, “Traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology of wild banana (Musa acuminata Colla): A review,” J. Ethnopharmacol., vol. 196, pp. 124–140, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2016.12.009.

[3] B. F. Lau, K. W. Kong, K. H. Leong, J. Sun, X. He, Z. Wang, M. R. Mustafa, T. C. Ling, and A. Ismail, “Banana inflorescence: Its bio-prospects as an ingredient for functional foods,” Trends Food Sci. Technol., vol. 97, pp. 14–28, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2019.12.023.

[4] S. Ramírez‐Bolaños, J. Pérez‐Jiménez, S. Díaz, and L. Robaina, “A potential of banana flower and pseudo‐stem as novel ingredients rich in phenolic compounds,” Int. J. Food Sci. Technol., vol. 56, no. 11, pp. 5601–5608, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1111/ijfs.15072.

[5] C. Panyayong and K. Srikaeo, “Foods from banana inflorescences and their antioxidant properties: An exploratory case in Thailand,” Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci., vol. 28, p. 100436, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgfs.2021.100436.

[6] M. D. O. Nogueira, M. de O. Guimarães, S. S. De Oliveira, F. M. N. de O. Freitas, and J. C. de S. Ferreira, “Perfil nutricional e benefícios de partes comestíveis não convencionais de bananeiras,” Brazilian J. Dev., vol. 8, no. 11, pp. 73473–73492, 2022, https://doi.org/10.34117/bjdv8n11-179.

[7] P. Aiemcharoen, S. Wichienchot, and D. Sermwittayawong, “Antioxidant and anti-diabetic activities of crude ethanolic extract from the banana inflorescence of musa (ABB group) namwa maliong,” Funct. Foods Heal. Dis., vol. 12, no. 4, p. 161, 2022, https://doi.org/10.31989/ffhd.v12i4.909.

[8] D. Soni and G. Saxena, “Complete nutrient profile of Banana flower: A review,” J. Plant Sci. Res., vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 263–267, 2021, https://doi.org/10.32381/JPSR.2021.37.02.6.

[9] W. F. Awedem, M. B. L. Achu, and E. T. Happi, “Nutritive Value of three varieties of banana and plantain blossoms from Cameroon,” Greener J. Agric. Sci., vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 052–061, 2015, https://doi.org/10.15580/GJAS.2015.2.012115009.

[10] P. Nisha and S. Mini, “In Vitro Antioxidant and Antiglycation Properties of Methanol Extract and Its Different Solvent Fractions of Musa paradisiaca L. (Cv. Nendran) Inflorescence,” Int. J. Food Prop., vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 399–409, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1080/10942912.2011.642050.

[11] R. Ramu, P. S. Shirahatti, F. Zameer, L. V. Ranganatha, and M. N. Nagendra Prasad, “Inhibitory effect of banana (Musa sp. var. Nanjangud rasa bale) flower extract and its constituents Umbelliferone and Lupeol on α-glucosidase, aldose reductase and glycation at multiple stages,” South African J. Bot., vol. 95, pp. 54–63, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2014.08.001.

[12] J. J. Bhaskar, P. V Salimath, and C. D. Nandini, “Stimulation of glucose uptake by Musa sp. (cv. elakki bale) flower and pseudostem extracts in Ehrlich ascites tumor cells,” J. Sci. Food Agric., vol. 91, no. 8, pp. 1482–1487, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.4337.

[13] J. J. Bhaskar, M. S, N. D. Chilkunda, and P. V. Salimath, “Banana (Musa sp. var. elakki bale) Flower and Pseudostem: Dietary Fiber and Associated Antioxidant Capacity,” J. Agric. Food Chem., vol. 60, no. 1, pp. 427–432, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1021/jf204539v.

[14] A. Krishnan, G. Deepakraj, N. Nishanth, and K. M. Anandkumar, “Autonomous walking stick for the blind using echolocation and image processing,” in 2016 2nd International Conference on Contemporary Computing and Informatics (IC3I), IEEE, Dec. 2016, pp. 13–16. https://doi.org/10.1109/IC3I.2016.7917927.

[15] K. Sitthiya, L. Devkota, M. B. Sadiq, and A. K. Anal, “Extraction and characterization of proteins from banana (Musa Sapientum L) flower and evaluation of antimicrobial activities,” J. Food Sci. Technol., vol. 55, no. 2, pp. 658–666, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-017-2975-z.

[16] M. M. Schmidt, R. C. Prestes, E. H. Kubota, G. Scapin, and M. A. Mazutti, “Evaluation of antioxidant activity of extracts of banana inflorescences (Musa cavendishii),” CyTA - J. Food, pp. 1–8, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1080/19476337.2015.1007532.

[17] R. China, S. Dutta, S. Sen, R. Chakrabarti, D. Bhowmik, S. Ghosh, and P. Dhar, “In vitro Antioxidant Activity of Different Cultivars of Banana Flower (Musa paradicicus L.) Extracts Available in India,” J. Food Sci., vol. 76, no. 9, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02395.x.

[18] B. S. Padam, H. S. Tin, F. Y. Chye, and M. I. Abdullah, “Antibacterial and Antioxidative Activities of the Various Solvent Extracts of Banana (Musa paradisiaca cv. Mysore) Inflorescences,” J. Biol. Sci., vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 62–73, 2012, https://doi.org/10.3923/jbs.2012.62.73.

[19] V. Revadigar, M. A. Al-Mansoub, M. Asif, M. R. Hamdan, A. M. S. A. Majid, M. Z. Asmawi, and V. Murugaiyah, “Anti-oxidative and cytotoxic attributes of phenolic rich ethanol extract of Musa balbisiana Colla inflorescence,” J. Appl. Pharm. Sci., vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 103–110, 2017, https://doi.org/10.7324/JAPS.2017.70518.

[20] Z. Sheng, M. Gu, W. Hao, Y. Shen, W. Zhang, L. Zheng, B. Ai, X. Zheng, and Z. Xu, “Physicochemical Changes and Glycation Reaction in Intermediate-Moisture Protein–Sugar Foods with and without Addition of Resveratrol during Storage,” J. Agric. Food Chem., vol. 64, no. 24, pp. 5093–5100, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.6b00877.

[21] S. Wang, Y. Yang, D. Xiao, X. Zheng, B. Ai, L. Zheng, and Z. Sheng, “Polysaccharides from banana (Musa spp.) blossoms: Isolation, identification and anti-glycation effects,” Int. J. Biol. Macromol., vol. 236, p. 123957, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123957.

[22] S. Rout and R. Banerjee, “Free radical scavenging, anti-glycation and tyrosinase inhibition properties of a polysaccharide fraction isolated from the rind from Punica granatum,” Bioresour. Technol., vol. 98, no. 16, pp. 3159–3163, 2007, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2006.10.011.

[23] R. Mapanao, T. Rangabpai, Y.-R. Lee, H.-W. Kuo, and W. Cheng, “The effect of banana blossom on growth performance, immune response, disease resistance, and anti-hypothermal stress of Macrobrachium rosenbergii,” Fish Shellfish Immunol., vol. 124, pp. 82–91, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsi.2022.03.041.

[24] H. S. Mostafa, “Banana plant as a source of valuable antimicrobial compounds and its current applications in the food sector,” J. Food Sci., vol. 86, no. 9, pp. 3778–3797, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.15854.

[25] S. Zhan-Wu, M. Wei-Hong, J. Zhi-Qiang, B. Yang, S. Zhi-Gao, D. Hua-Ting, G. Jin-He, L. Jing-Yang, and H. Li-Na, “Investigation of dietary fiber, protein, vitamin E and other nutritional compounds of banana flower of two cultivars grown in China,” African J. Biotechnol., vol. 9, no. 25, pp. 3888–3895, 2010, https://doi.org/10.5897/AJB2010.000-3262.

[26] K. S. Wickramarachchi and S. L. Ranamukhaarachchi, “Preservation of Fiber-Rich Banana Blossom as a Dehydrated Vegetable,” ScienceAsia, vol. 31, no. 3, p. 265, 2005, https://doi.org/10.2306/scienceasia1513-1874.2005.31.265.

[27] S. Muchahary, C. Nickhil, G. Jeevarathinam, S. Rustagi, and S. C. Deka, “Encapsulation of quercetin fraction from Musa balbisiana banana blossom in chitosan alginate solution, its optimization and characterizations,” Int. J. Biol. Macromol., vol. 264, p. 130786, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.130786.

[28] S. Muchahary and S. C. Deka, “Impact of supercritical fluid extraction, ultrasound‐assisted extraction, and conventional method on the phytochemicals and antioxidant activity of bhimkol (Musa balbisiana) banana blossom,” J. Food Process. Preserv., vol. 45, no. 7, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1111/jfpp.15639.

[29] R. E. Bruckdorfer, O. B. Büttner, and G. Mau, “‘Flavor, fun, and vitamins’? Consumers’ lay beliefs about child-oriented food products,” Appetite, vol. 205, p. 107773, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2024.107773.

[30] M. S. Hossain, M. A. Wazed, S. Asha, M. A. Hossen, S. N. M. Fime, S. T. Teeya, L. Y. Jenny, D. Dash, and I. M. Shimul, “Flavor and Well‐Being: A Comprehensive Review of Food Choices, Nutrition, and Health Interactions,” Food Sci. Nutr., vol. 13, no. 5, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.70276.

[31] P. Silva, R. Araújo, F. Lopes, and S. Ray, “Nutrition and Food Literacy: Framing the Challenges to Health Communication,” Nutrients, vol. 15, no. 22, p. 4708, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15224708.

[32] S. Nakano and A. Washizu, “Aiming for better use of convenience food: an analysis based on meal production functions at home,” J. Heal. Popul. Nutr., vol. 39, no. 1, p. 3, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-020-0211-3.

[33] C. J. Villegas-Ornelas, S. G. Sáyago-Ayerdi, V. M. Zamara-Gasga, and F. J. Blancas-Benítez, “The impact of composite flours in the in vitro gastrointestinal digestion on phenolic compounds in bakery products,” Food Res. Int., vol. 221, p. 117574, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2025.117574.

[34] A. Nicolosi, V. R. Laganà, and D. Di Gregorio, “Habits, Health and Environment in the Purchase of Bakery Products: Consumption Preferences and Sustainable Inclinations before and during COVID-19,” Foods, vol. 12, no. 8, p. 1661, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12081661.

[35] H. T. Kodithuwakku and P. D. A. Abeysundara, “Exploring the nutritional benefits of a ready-to-eat vegan sandwich filler developed with tender jackfruit, seaweed, banana blossom and soy flour: Formulation and quality analysis,” Food Chem. Adv., vol. 8, p. 101039, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.focha.2025.101039.

[36] X. Cheng, D. Xiao, X. Zheng, Y. Yang, L. Zheng, B. Ai, S. Wang, and Z. Sheng, “Nano-engineered carbon dots from banana blossoms inhibit advanced glycation end products formation in bakery foods: A mechanistic study through multi-stage kinetic modeling,” LWT, vol. 222, p. 117619, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2025.117619.

[37] R. Vijaya Vahini, F. Lamiya, and C. Sowmya, “A study on preparation and quality assessment of fermented banana blossom (Musa Acuminate Colla),” Food Humanit., vol. 1, pp. 1188–1193, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foohum.2023.09.016.

[38] I. S. Rahayu, B. Saragih, and R. I. Mulyani, “The Effect of the Substitution of Banana Blossom Flour (Musa paradisiaca) and Mung Bean (Vigna radiata) on Proteins, Fiber, and Steamed Brownies Sensory,” Formosa J. Sci. Technol., vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 861–874, 2023, https://doi.org/10.55927/fjst.v2i3.3198.

[39] P. A. da Silva Neto, M. L. P. Aires, F. E. T. Cunha, L. M. R. da Silva, P. H. M. de Sousa, and S. T. Gouveia, “Processing of banana mangará: Microbiological evaluation and development of preserves and appetizers with a focus on sensory qualities and gastronomic applications,” Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci., vol. 38, p. 101028, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgfs.2024.101028.

[40] M. Rosita, H. Evanuarini, A. Susilo, P. P. Rahayu, and I. W. Nursita, “The Effect of Banana Blossom Flour Addition on the Physical Quality of Chicken Sausages,” BIO Web Conf., vol. 191, p. 00038, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1051/bioconf/202519100038.

[41] M. G. Priebe and J. R. McMonagle, “Effects of Ready-to-Eat-Cereals on Key Nutritional and Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review,” PLoS One, vol. 11, no. 10, p. e0164931, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0164931.

[42] E. J. Derbyshire and C. H. S. Ruxton, “A Systematic Review of Evidence on the Role of Ready-to-Eat Cereals in Diet and Non-Communicable Disease Prevention,” Nutrients, vol. 17, no. 10, p. 1680, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17101680.

[43] M. Košutić, I. Djalović, J. Filipović, S. Jakšić, V. Filipović, M. Nićetin, and B. Lončar, “The Development of Novel Functional Corn Flakes Produced from Different Types of Maize (Zea mays L.),” Foods, vol. 12, no. 23, p. 4257, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12234257.

[44] C. Kesre and M. T. Masatcioglu, “Physical characteristics of corn extrudates supplemented with red lentil bran,” LWT, vol. 153, p. 112530, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2021.112530.

[45] S. Afrin Zinia, A. Rahim, M. A. Latif Jony, A. Ara Begum, and M. A. Rahman Mazumder, “The Roles of Okara Powder on the Processing and Nutrient Content of Roti and Paratha,” Int. J. Agric. Environ. Sci., vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 18–23, 2019, https://doi.org/10.14445/23942568/IJAES-V6I2P104.

[46] M. L. Estell, E. M. Barrett, K. R. Kissock, S. J. Grafenauer, J. M. Jones, and E. J. Beck, “Fortification of grain foods and NOVA: the potential for altered nutrient intakes while avoiding ultra-processed foods,” Eur. J. Nutr., vol. 61, no. 2, pp. 935–945, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-021-02701-1.

[47] Y. Wang and C. Jian, “Sustainable plant-based ingredients as wheat flour substitutes in bread making,” npj Sci. Food, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 49, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-022-00163-1.

[48] J. Lewandowicz, J. Le Thanh-Blicharz, P. Jankowska, and G. Lewandowicz, “Functionality of Alternative Flours as Additives Enriching Bread with Proteins,” Agriculture, vol. 15, no. 8, p. 851, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15080851.

[49] H. Marta, C. Febiola, Y. Cahyana, H. R. Arifin, F. Fetriyuna, and D. Sondari, “Application of Composite Flour from Indonesian Local Tubers in Gluten-Free Pancakes,” Foods, vol. 12, no. 9, p. 1892, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12091892.

[50] D. R. Pyasi, “Potential health benefits and industrial scope of arrowroot,” Int. J. Adv. Biochem. Res., vol. 8, no. 3S, pp. 282–284, 2024, https://doi.org/10.33545/26174693.2024.v8.i3Sd.722.

[51] G. F. Nogueira, F. M. Fakhouri, and R. A. de Oliveira, “Extraction and characterization of arrowroot (Maranta arundinaceae L.) starch and its application in edible films,” Carbohydr. Polym., vol. 186, no. December 2017, pp. 64–72, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.01.024.

[52] S. Sumardiono, B. Jos, M. F. Z. Antoni, Y. Nadila, and N. A. Handayani, “Physicochemical properties of novel artificial rice produced from sago, arrowroot, and mung bean flour using hot extrusion technology,” Heliyon, vol. 8, no. 2, p. e08969, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08969.

[53] D. Damat, R. Anggriani, R. H. Setyobudi, and P. Soni, “Dietary fiber and antioxidant activity of gluten-free cookies with coffee cherry flour addition,” Coffee Sci., vol. 14, no. 4, p. 493, 2019, https://doi.org/10.25186/cs.v14i4.1625.

[54] M. K. S. Malki, J. A. A. C. Wijesinghe, R. H. M. K. Ratnayake, and G. C. Thilakarathna, “Variation in Colour Attributes of Arrowroot (Maranta arundinacea) Flour from Five Different Provinces in Sri Lanka as a Potential Alternative for Wheat Flour,” IPS J. Nutr. Food Sci., vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 11–14, 2022, https://doi.org/10.54117/ijnfs.v1i2.14.

[55] M. K. S. Malki, J. A. A. C. Wijesinghe, R. H. M. K. Ratnayake, and G. C. Thilakarathna, “Characterization of arrowroot (Maranta arundinacea) starch as a potential starch source for the food industry,” Heliyon, vol. 9, no. 9, p. e20033, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20033.

[56] A. Díaz, R. Bomben, C. Dini, S. Z. Viña, M. A. García, M. Ponzi, and N. Comelli, “Jerusalem artichoke tuber flour as a wheat flour substitute for biscuit elaboration,” LWT, vol. 108, pp. 361–369, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2019.03.082.

[57] J. Tarique, S. M. Sapuan, A. Khalina, S. F. K. Sherwani, J. Yusuf, and R. A. Ilyas, “Recent developments in sustainable arrowroot (Maranta arundinacea Linn) starch biopolymers, fibres, biopolymer composites and their potential industrial applications: A review,” J. Mater. Res. Technol., vol. 13, pp. 1191–1219, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2021.05.047.

[58] A. H. M. Firdaus, S. M. Sapuan, V. U. Siddiqui, A. Atiqah, and E. S. Zainudin, “Mechanical, physical and morphological properties of arrowroot starch reinforced arrowroot nanocrystalline cellulose biopolymer nanocomposites film,” Biomass and Bioenergy, vol. 202, p. 108230, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2025.108230.

[59] S. Sood, K. Li, C. Sand, L. Pal, and M. A. Hubbe, “Fruit wastes: a source of value-added products,” in Adding Value to Fruit Wastes, 2024, pp. 3–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-13842-3.00001-0.

[60] Y. Huang, P. Kou, J. Luo, C. Chen, J. Li, Z. Lai, L. Miao, and Y. Chen, “Effect of Storage Temperature on Fruit Hardness and Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Red Peeled Banana (Musa acuminata Hongmeiren),” HortScience, vol. 59, no. 11, pp. 1667–1673, 2024, https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI18192-24.

[61] S. N. Rahmadhia, D. R. Toni, and A. Fitriani, “Physical Characteristics of Kepok Banana Bud (Musa paradisiaca Linn.) Flakes With Variations of Mocaf Flour,” J. Keteknikan Pertan., vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 77–92, 2024, https://doi.org/10.19028/jtep.012.1.77-92.

[62] A. Fitriani, D. R. Toni, and S. N. Rahmadhia, “Chemical Characteristics of Kepok Banana Bud (Musa Paradisiaca Linn.) Flakes with Variations of Mocaf Flour,” J. Funct. Food Nutraceutical, pp. 97–105, 2024, https://doi.org/10.33555/jffn.v5i2.114.

[63] S. K. Putri and A. Setiyoko, “Proximate and Texture Profile Analysis of Gluten-Free Cookies Made from Black Glutinous Rice and Mung Bean Flour,” J. Agri-Food Sci. Technol., vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 107–116, 2025, https://doi.org/10.12928/jafost.v6i2.12717.

[64] S. Langyan, R. Bhardwaj, J. Radhamani, R. Yadav, R. K. Gautam, S. Kalia, and A. Kumar, “A Quick Analysis Method for Protein Quantification in Oilseed Crops: A Comparison With Standard Protocol,” Front. Nutr., vol. 9, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.892695.

[65] AOAC International, Official Methods of Analysis Association of Official Analytical Chemists. AOAC International, 2005, https://books.google.co.id/books?id=QY_wwAEACAAJ.

[66] J. A. Adeyanju, G. O. Babarinde, B. F. Olanipekun, I. F. Bolarinwa, and S. O. Oladokun, “Quality assessment of flour and cookies from wheat, African yam bean and acha flours,” Food Res., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 371–379, 2021, https://doi.org/10.26656/fr.2017.5(1).370.

[67] N. Salma, A. Setiyoko, Y. P. Sari, and Y. Rahmadian, “Effect of wheat flour and yellow pumpkin flour ratios on the physical, chemical properties, and preference level of cookies,” J. Agri-Food Sci. Technol., vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 59–70, 2024, https://doi.org/10.12928/jafost.v4i2.7882.

[68] U. Patil, M. Chanchi Prashanthkumar, K. Sharma, S. Nile, B. Zhang, L. Ma, and S. Benjakul, “Development of whole wheat functional cookies fortified with natural iron-rich hemeproteins from asian seabass gills: Nutritional, textural, and sensory properties,” Food Biosci., vol. 66, p. 106276, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2025.106276.

[69] C. Verbeke, E. Debonne, S. Versele, F. Van Bockstaele, and M. Eeckhout, “Technological Evaluation of Fiber Effects in Wheat-Based Dough and Bread,” Foods, vol. 13, no. 16, p. 2582, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13162582.

[70] I. G. A. M. Putra, L. D. Rna Fajarini, P. J. N. Dewi, W. A. Muzakki, and N. S. Ibrahim, “Sago Porridge Enriched with Red Dragon Fruit (Hylocereus polyrhizus) Extract: A Functional Food with Enhanced Sensory and Nutritional Properties,” J. Agri-Food Sci. Technol., vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 98–106, 2025, https://doi.org/10.12928/jafost.v6i2.12847.

[71] S. Sinthusamran, S. Benjakul, K. Kijroongrojana, and T. Prodpran, “Chemical, physical, rheological and sensory properties of biscuit fortified with protein hydrolysate from cephalothorax of Pacific white shrimp,” J. Food Sci. Technol., vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 1145–1154, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-019-03575-2.

[72] M. N. Azkia and S. B. Wahjuningsih, “Sensory Characteristics of Mocaf-Substituted Noodles Enriched with Latoh (Caulerpa lentillifera),” J. Agri-food Sci. Technol., vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 141–151, 2025, https://doi.org/10.12928/jafost.v6i3.14145.

[73] S. N. N. Makiyah, I. Setyawati, S. N. Rahmadhia, S. Tasminatun, and M. Kita, “Comparison of yam composite cookies sensory characteristic between sugar and stevia sweeteners,” J. Agri-Food Sci. Technol., vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 120–133, 2024, https://doi.org/10.12928/jafost.v5i2.10211.

[74] H. Barakat, R. M. Alhomaid, and R. Algonaiman, “Production and evaluation of kleija-like biscuits formulated with sprouted mung beans,” Foods, vol. 14, no. 9, p. 1571, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14091571.

[75] F. C. Agustia, R. Salma, S. A. Hamidah, K. R. Dewi, and S. Sanayei, “Total Phenolic Content and Hedonic Quality of Germinated Jack Bean Tempeh at Different Fermentation Times and Packaging Types,” J. Agri-Food Sci. Technol., vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 73–86, 2025, https://doi.org/10.12928/jafost.v6i2.12698.

[76] I. A. T. Wahyuniari, I. G. A. M. Putra, M. D. D. Devani, P. W. D. Wiguna, and D. P. Kartika, “Sensory evaluation and antioxidant activity of functional ice cream with the ratio of cardamom powder and dragon fruit peel puree,” J. Agri-Food Sci. Technol., vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 117–128, 2025, https://doi.org/10.12928/jafost.v6i2.12896.

[77] N. I. Umam, R. R. Mariana, A. G. Gunawan, A. A. Prihanto, and H. Muyasyaroh, “Development of New Antidiabetic Drink from Sargassum sp.: Total Phenolic Content, α-Glucosidase Inhibition, and Sensory Analysis,” J. Agri-Food Sci. Technol., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 63–72, 2025, https://doi.org/10.12928/jafost.v6i1.12596.

[78] Y. S. K. Dewi, N. I. Rosanti, and T. Rahayuni, “Physicochemical and Sensory Characteristics of ‘Terong Asam’ (Solanum ferox Linn) Dry Sweetmeat at Various Concentrations of Sugar,” J. Agri-Food Sci. Technol., vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 21–27, 2022, https://doi.org/10.12928/jafost.v3i1.6505.

[79] M. Hayes, “Measuring Protein Content in Food: An Overview of Methods,” Foods, vol. 9, no. 10, p. 1340, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9101340.

[80] Y. S. Vershinina, I. V. Mitin, A. V. Garmay, G. K. Sugakov, and I. A. Veselova, “Simple and Robust Approach for Determination of Total Protein Content in Plant Samples,” Foods, vol. 14, no. 3, p. 358, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14030358.

[81] D. Chen, J. Song, H. Yang, S. Xiong, Y. Liu, and R. Liu, “Effects of Acid and Alkali Treatment on the Properties of Proteins Recovered from Whole Gutted Grass Carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) Using Isoelectric Solubilization/Precipitation,” J. Food Qual., vol. 39, no. 6, pp. 707–713, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1111/jfq.12236.

[82] S. M. Aravind, R. K. S. Mattshe, P. Prasanna, S. P. Saran, D. Dharanesh, S. R. Kumar, and A. Kishore, “Valorization and characterization of red banana (Musa acuminata) peel powder for the development of functional cookies,” Food Humanit., vol. 5, p. 100683, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foohum.2025.100683.

[83] N. Senevirathna and A. Karim, “Banana inflorescence as a new source of bioactive and pharmacological ingredients for food industry,” Food Chem. Adv., vol. 5, p. 100814, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.focha.2024.100814.

[84] Hardoko, E. Suprayitno, T. D. Sulistiyati, B. B. Sasmito, A. Chamidah, M. A. P. Panjaitan, J. E. Tambunan, and H. Djamaludin, “Banana blossom addition to increase food fiber in tuna (Thunnus sp.) floss product as functional food for degenerative disease’s patient,” IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci., vol. 1036, no. 1, p. 012095, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1036/1/012095.

[85] O. D. Indriani and A. N. Khairi, “Physico-chemical Characteristics of Jelly Drink with Variation of Red Dragon Fruit Peel (Hylocereus polyrhizus) and Additional Sappan Wood (Caesalpinia sappan),” J. Agri-Food Sci. Technol., vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 37–48, 2023, https://doi.org/10.12928/jafost.v4i1.7069.

[86] R. G. M. van der Sman and E. Schenk, “Causal factors concerning the texture of French fries manufactured at industrial scale,” Curr. Res. Food Sci., vol. 8, p. 100706, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crfs.2024.100706.

[87] D. Dziki, A. Krajewska, and P. Findura, “Particle Size as an Indicator of Wheat Flour Quality: A Review,” Processes, vol. 12, no. 11, p. 2480, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12112480.

[88] A. Fitriani, M. N. Haliza, N. P. Utami, I. Nyambayo, S. Sanayei, and S. N. Rahmadhia, “Texture Profile Analysis of Lamtoro Gung (Leucaena leucocephala ssp. Glabrata (Rose) S. Zarate) Tempeh,” J. Agri-Food Sci. Technol., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 65–72, 2024, https://doi.org/10.12928/jafost.v5i1.10226.

[89] M. A. Bastomy and S. N. Rahmadhia, “The Effect of Chitosan-Based Edible Coating on The Moisture Content, Texture, and Microbial Count of Chicken Sausages,” J. Ilmu-Ilmu Peternak., vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 67–79, 2025, https://doi.org/10.21776/ub.jiip.2025.035.01.7.

[90] J. S. Myers, S. R. Bean, F. M. Aramouni, X. Wu, and K. A. Schmidt, “Textural and functional analysis of sorghum flour cookies as ice cream inclusions,” Grain Oil Sci. Technol., vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 100–111, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaost.2022.12.002.

[91] M. F. Z. Mulla, E. Mullins, R. Lynch, and E. Gallagher, “A mixture design approach to investigate the impact of raw and processed chickpea flour on the techno-functional properties in a bakery application,” LWT, vol. 229, p. 118206, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2025.118206.

[92] R. P. F. Guiné, “Textural Properties of Bakery Products: A Review of Instrumental and Sensory Evaluation Studies,” Appl. Sci., vol. 12, no. 17, p. 8628, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/app12178628.

[93] A. Panghal, N. Chhikara, and B. S. Khatkar, “Effect of processing parameters and principal ingredients on quality of sugar snap cookies: a response surface approach,” J. Food Sci. Technol., vol. 55, no. 8, pp. 3127–3134, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-018-3240-9.

[94] F. Ma and B.-K. Baik, “Soft wheat quality characteristics required for making baking powder biscuits,” J. Cereal Sci., vol. 79, pp. 127–133, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcs.2017.10.016.

[95] Z. Zhang, X. Fan, X. Yang, C. Li, R. G. Gilbert, and E. Li, “Effects of amylose and amylopectin fine structure on sugar-snap cookie dough rheology and cookie quality,” Carbohydr. Polym., vol. 241, p. 116371, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116371.

[96] M. Schopf and K. A. Scherf, “Water Absorption Capacity Determines the Functionality of Vital Gluten Related to Specific Bread Volume,” Foods, vol. 10, no. 2, p. 228, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10020228.

[97] H. Sapirstein, Y. Wu, F. Koksel, and R. Graf, “A study of factors influencing the water absorption capacity of Canadian hard red winter wheat flour,” J. Cereal Sci., vol. 81, pp. 52–59, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcs.2018.01.012.

[98] D. Sfayhi‐Terras, N. Hadjyahia, and Y. Zarroug, “Effect of soaking time and temperature on water absorption capacity and dimensional changes of bulgur,” Cereal Chem., vol. 98, no. 4, pp. 851–857, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1002/cche.10427.

[99] M. Mohammed, A. J. M. Jawad, A. M. Mohammed, J. K. Oleiwi, T. Adam, A. F. Osman, O. S. Dahham, B. O. Betar, S. C. B. Gopinath, and M. Jaafar, “Challenges and advancement in water absorption of natural fiber-reinforced polymer composites,” Polym. Test., vol. 124, p. 108083, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymertesting.2023.108083.

[100] L. A. Alahmari, “Dietary fiber influence on overall health, with an emphasis on CVD, diabetes, obesity, colon cancer, and inflammation,” Front. Nutr., vol. 11, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1510564.

[101] C. Opperman, M. Majzoobi, A. Farahnaky, R. Shah, T. T. H. Van, V. Ratanpaul, E. W. Blanch, C. Brennan, and R. Eri, “Beyond soluble and insoluble: A comprehensive framework for classifying dietary fibre’s health effects,” Food Res. Int., vol. 206, p. 115843, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2025.115843.

[102] W. Sztupecki, L. Rhazi, F. Depeint, and T. Aussenac, “Functional and Nutritional Characteristics of Natural or Modified Wheat Bran Non-Starch Polysaccharides: A Literature Review,” Foods, vol. 12, no. 14, p. 2693, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12142693.

[103] A. B. Adepeju, D. M. Aluko, A. O. Olugbuyi, A. M. Oyinloye, and O. O. Adeniran, “Assessment of mineral content, techno-functional properties and colour of an extruded breakfast cereals using yellow maize, sorghum and date palm,” Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 6, p. e27650, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e27650.

[104] A. Bielaszka, W. Staśkiewicz-Bartecka, A. Kiciak, M. Wieczorek, and M. Kardas, “Color and Its Effect on Dietitians’ Food Choices: Insights from Tomato Juice Evaluation,” Beverages, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 70, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages10030070.

[105] C. Chen, M. Espinal‐Ruiz, A. Francavilla, I. J. Joye, and M. G. Corradini, “Morphological changes and color development during cookie baking—Kinetic, heat, and mass transfer considerations,” J. Food Sci., vol. 89, no. 7, pp. 4331–4344, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.17117.

[106] Z. Bahreini, M. Abedi, A. Ashori, and A. Parach, “Extraction and characterization of anthocyanin pigments from Iris flowers and metal complex formation,” Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 11, p. e31795, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e31795.

[107] S. Shameena, P. R. G. Lekshmi, P. P. Gopinath, P. Gidagiri, and S. Kanagarajan, “Dynamic transformations in fruit color, bioactive compounds, and textural characteristics of purple-fleshed dragon fruit (Hylocereus costaricensis) across fruit developmental stages under humid tropical climate,” Horticulturae, vol. 10, no. 12, p. 1280, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae10121280.

[108] B. C. K. Ly, E. B. Dyer, J. L. Feig, A. L. Chien, and S. Del Bino, “Research Techniques Made Simple: Cutaneous Colorimetry: A Reliable Technique for Objective Skin Color Measurement,” J. Invest. Dermatol., vol. 140, no. 1, pp. 3-12.e1, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2019.11.003.

[109] N. Osakabe, T. Shimizu, Y. Fujii, T. Fushimi, and V. Calabrese, “Sensory Nutrition and Bitterness and Astringency of Polyphenols,” Biomolecules, vol. 14, no. 2, p. 234, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14020234.

[110] V. A. Silva Vidal, S. S. Juel, K. Mukhatov, I.-J. Jensen, and J. Lerfall, “Impact of processing conditions on the rehydration kinetics and texture profile of freeze-dried carbohydrates sources,” J. Agric. Food Res., vol. 19, p. 101693, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2025.101693.

[111] J. Peng, L. Lu, K.-X. Zhu, X.-N. Guo, Y. Chen, and H.-M. Zhou, “Effect of rehydration on textural properties, oral behavior, kinetics and water state of textured wheat gluten,” Food Chem., vol. 376, p. 131934, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131934.

Safinta Nurindra Rahmadhia (Banana Blossom as a Novel Ingredient in The Zero Waste Strategy: Application in Flakes)