ISSN: 2685-9572 Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro

Vol. 8, No. 1, February 2026, pp. 33-50

Legal and Public Health Governance for Sustainable Integration of Mobile Health (mHealth) Technologies in East Africa

Paul Atagamen Aidonojie 1, George Mulingi Mugabe 2, Esther Chetachukwu Aidonojie 3, Muwaffiq Jufri 4, Mundu M. Mustafa 5, Collins Ekpenisi 6, Obieshi Eregbuonye 7, Godswill Owoche Antai 8, Mercy Okpoko 9, Uzoho Kelechi 10, Khalid Saleh Y. Alammari 11

1,6,8 School of Law, Kampala International University, Kampala, Uganda

2 Ashesi University, Berekuso, Ghana

3 Department of Public Health, Kampala International University, Kampala, Uganda

4 Fakultas Hukum, Universitas Trunojoyo Madura, Indonesia

5 Kampala International University, Kampala, Uganda

7 Faculty of Law, Edo State University, Edo State, Nigeria

9 Faculty of Management, Law and Social Science, University of Bradford, United Kingdom

10 Hutton School of Business, University of the Cumberlands, United States

11 College of Law, Prince Mohammad Bin Fahd University, Saudi Arabia

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 11 October 2025 Revised 27 December 2025 Accepted 07 January 2026 |

|

Mobile health (mHealth), which comprises mobile health applications, telemedicine, SMS-based treatments, and wearable health monitors, has the power to change healthcare delivery, but at the same-time, it is going through a rapid developmental phase that regulators cannot keep up with. This is considered a necessity in balancing the Integration of mHealth technology innovation through enhanced laws within East Africa. It is in view of this that this examines the legal and public health framework in integrating mHealth technology in enhancing the healthcare system within East Africa. The study adopts a doctrinal and systematic analytical method of study directed by the PRISMA framework, allowing thorough legal analysis while at the same time guaranteeing a transparent, stringent, and comprehensive review of related literature. The study found that fragmentation of laws, lack of centralized public health and data governance, unequal access to mHealth services, and constraints on innovation, weakens the integration and regulation of mHealth. Hence, the study recommends and concludes that for effective integration of mHealth in enhancing the public health care system, the research insists on a unified legal system that states unambiguously which data protection benchmarks apply, what the liability conditions are, what the integration of different systems and regulations requirements is, and how to coordinate among different countries' regulators. Besides that, it suggests measures for strengthening the capacity of the targeted groups, such as: medical professionals, trainees, users’ digital literacy campaigns, and local mHealth technology developers’ institutions’ support. |

Keywords: Legal; Public Health; mHealth; Technologies; East Africa |

Corresponding Author: Paul Atagamen Aidonojie, School of Law, Kampala International University, Kampala, Uganda. Email: paul.aidonojie@kiu.ac.ug |

This work is open access under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: P. A. Aidonojie, G. M. Mugabe, E. C. Aidonojie, M. Jufri, M. M. Mustafa, C. Ekpenisi, O. Eregbuonye, G. A. Owoche, M. Okpoko, U. Kelechi, and K. S. Y. Alammari, “Legal and Public Health Governance for Sustainable Integration of Mobile Health (mHealth) Technologies in East Africa,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 33-50, 2026, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v8i1.14943. |

- INTRODUCTION

Healthy societies are built not only in enhanced digitalized hospitals such as mHealth, but also by the wisdom of laws and the power of institutions that ensure effective regulation for the good of the public. Health system delivery across East Africa involves complex interactions of infrastructure, policy, and access to care [1]. While many developed countries have made great strides in access to care over the past two decades, countries such as Tanzania, Uganda, and Kenya are also gradually catching up to adapt to the current trend of health delivery, irrespective of the structural challenges, such as an insufficiently trained workforce capacity, and weak infrastructure, most especially in rural health infrastructure [2]. Hence, given these challenges, public health systems in these countries may face a double burden of communicable disease alongside non-communicable disease. Addressing these challenges has led governments and other relevant health partners in these countries to consider new and innovative ways to improve service delivery [3], one of which is the use of mobile health (mHealth) technology to enhance healthcare access, monitoring, and management through mobile technology.

MHealth refers to the use of technology-enabled tools, whereby mobile and other digital tools support the delivery of preventive care, maternal and child health services, and facilitate data-informed decision-making at the frontline. In health systems of East Africa, digital health tools (mHealth) are viewed as a solution to health system challenges, as well as providing a mechanism to support a wider health coverage [4]. The capacity of mobile technology to navigate the boundaries of geography, cost, and human resources through remote consultation, patient tracking, and data collection brings numerous opportunities and benefits to the East African Community. Moreover, mobile phone penetration and usage rates have surpassed 70% in Tanzania, Uganda, and Kenya, and the possibilities of mHealth to improve and transform health service delivery systems are becoming more evident [5]. Although it must be noted that mHealth, although not prominent or common in most East African Community member states, is gradually creeping in and revolutionizing their health sector in some countries. In Kenya, programs like M-TIBA and M-Pesa Health have transformed patient communication and connections to healthcare financing [6]. Meanwhile, Uganda's mTrac and mHealth Uganda programs serve as both surveillance and reporting tools for diseases in real-time, at the community and district levels [7]. In Tanzania, the Wazazi Nipendeni maternal health SMS program improved maternal and child health outcomes through SMS reminders and education. These national programs provide evidence that digital health tools are more than just technology; it is a social equalizer and a rebranding of the health sector for effective and efficient delivery.

Therefore, despite this promising technological adoption, a fragmented and evolving legal landscape threatens to undermine its potential. The sustainability and scalability of mHealth interventions in East Africa will depend heavily on the legal and public health environment in which they exist [8]. The legal environment in the region is still fairly evolving and fragmented regarding data protection laws, cybersecurity protections, and ethical and liability frameworks as it concerns a digital technology-driven healthcare system. Although Uganda's Data Protection and Privacy Act (2019), Kenya's Data Protection Act (2019), Tanzania's Personal Data Protection Act (2022) and several of these countries' laws are strides toward new regulation of digital health data [9], implementation and lack of harmonization in addressing cross-border situations may pose a challenge [10]. Moreover, the legal environment around the recognition of digital medical records, cross-border sharing of health data and documentation, and other absent legal contexts present barriers to regional integration of health services [11]. Consequently, the research adopts a doctrinal method of study in examining the legal and public health frameworks that exist across the East Africa region, comprising Tanzania, Uganda, and Kenya, to identify the implications of such frameworks on the uptake of mHealth technologies [12]. The research will engage in a broader discussion of regional cooperation and the harmonization of legal frameworks to achieve improved governance of digital health and public health outcomes within the East African Community. The study will also provide recommendations for the legal and institutional context that promote the equitable, appropriate, and sustainable use of digital health tools in East Africa.

This research adds to the existing knowledge by presenting a comparative legal analysis of mobile health regulations in East Africa, a region that is still considered a blank spot on the map of local academic research. Thus, it links public health discussions with legal analysis, illuminating the issue of fragmented regulation and its adverse effects on the quality of health. Lastly, it suggests legally and politically sensitive recommendations for the context to reinforce mHealth governance in the area.

- LITERATURE REVIEW

True wealth of a nation does not rest in gold or oil, as it has always been in most African countries [13], but in the health of its people, which is most often addressed through an effective healthcare delivery system [14]. The state of public health in East Africa illustrates advancements and continuing challenges [15]. Countries such as Uganda, Tanzania, and Kenya have made great advances in healthcare access through national health insurance programs, immunization programs [16], and health surveillance systems, all of which have contributed to reductions in child mortality, improvements in maternal health [17], as well as improvements in responses related to HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases (e.g., tuberculosis and malaria) [18]. In Uganda, the public health environment is shaped by the government's progress in providing a wider healthcare coverage as part of its responsibility provided for in the National Health Policy and Vision 2040. This mission drives response to epidemics and strengthens community health extension programs [19]. In Tanzania, there has been an opportunity to strengthen primary healthcare service provisioning through the 5th Health Sector Strategic Plan (HSSP V), which includes greater access to medicines [20]. Also, incremental innovations in healthcare access and policy reform in Kenya have shifted the momentum towards a wider health coverage with pilot programs such as Universal Health Coverage (UHC Up), and changes with the National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF) program [21].

Nonetheless, the challenges of inequality, affordability, and service delivery fragmentation are particularly prevalent among informal workers and the rural population [22]. Population growth and urbanization, along with inadequate public health facilities [23], continue to place pressures on health systems [24]. Rural dwellers are most often disadvantaged, facing long journeys to reach a health facility or visit a medical professional, which results in several persons not getting adequate healthcare [25]. In East Africa, another significant challenge for public health is the burden of both communicable and non-communicable diseases [26]. This is concerning the fact that, even when health systems continue to respond to communicable diseases such as malaria [27], HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and several other diseases, however, the rising burden of non-communicable diseases such as hypertension [28], diabetes, and cancers puts pressure on already existing health system capacities and budgets [29]. In addition to that, the COVID-19 pandemic has also revealed the strengths and weaknesses of East African health systems [30]. In times of health crisis, there is a need for more intervention through sophisticated means that are beyond the traditional healthcare system [31]. The processes associated with this epidemiological transition will require new systems and structures that focus on timely interventive prevention, short-term diagnosis, sustained monitoring functions and an accessible healthcare system [32]. Hence, the need for digital solutions that enable healthcare delivery.

The advent of mobile health (mHealth) technologies offers a promising response to these challenges [33]. With mobile phone penetration rates of over 70% in most East African countries, mHealth specifically has the opportunity to bridge patients and healthcare providers in remote or underserved communities [34]. They can do this by using apps to provide health information, remote consultations, and be able to collect health information that informs mHealth applications [35]. Hence, provide a prompt and effective response in addressing communicable and non-communicable disease risk factors [36]. In this regard, the mTrac program in Uganda, the M-TIBA health financing platform in Kenya, Wazazi Nipendeni in Tanzania, are examples of how digital interventions are engaged to complement traditional health systems, improve health outcomes [37]. Thus, the need for mHealth in East Africa emerges not just from a deficiency of public health systems alone [38], but from an understanding that technology can amplify their reach, efficiency and effectiveness [39]. mHealth provides a sustainable pathway to achieve a wider health coverage by solving gaps in communication [40], data management, and access to effective service delivery. As mobile connectivity expands rapidly in the region [41], it is necessary to include digital health in national health plans, and this is an essential first step toward achieving a healthier and more resilient East Africa [42].

- METHODS

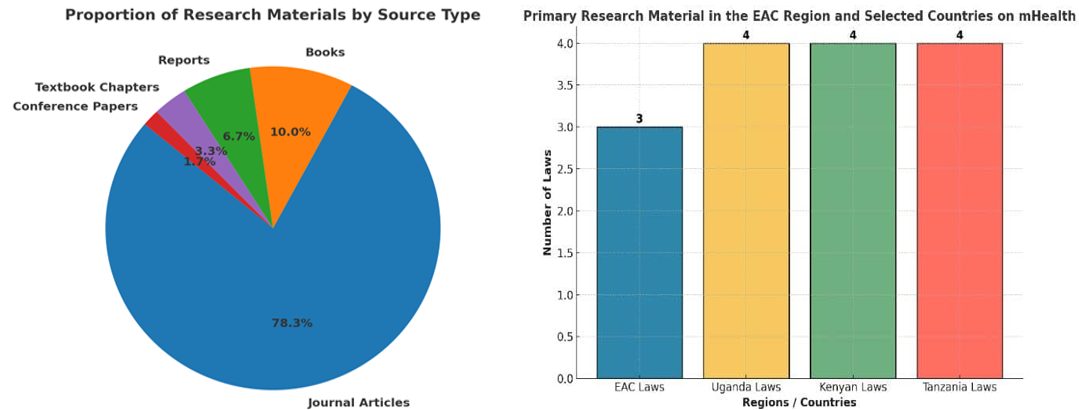

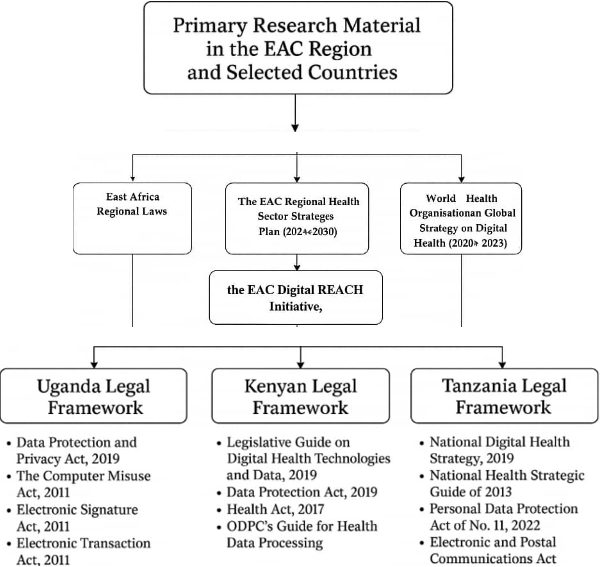

The study adopts a doctrinal method and the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) framework, which is the systematic process used to gather materials for the doctrinal legal analysis. The essence of adopting the PRISMA Guide is to ensure a comprehensive and unbiased identification of all relevant legal instruments and scholarly commentary, minimizing selection bias. Concerning this, the study relied on primary and secondary doctrinal research material. Hence, this entails a systematic search and selection, in addition to a critical appraisal, of several prior and existing legal, policy, and scholarly documentation about mHealth governance in the East African context. Hence, the study will consider national legal instruments, namely, constitutions, health sector acts, data protection acts, ICT regulations, and regional legal frameworks under the auspices of the East African Community (EAC) that may have relevance in integrating digital health. In this regard, data obtained from primary sources are therefore presented as follows in Figure 1.

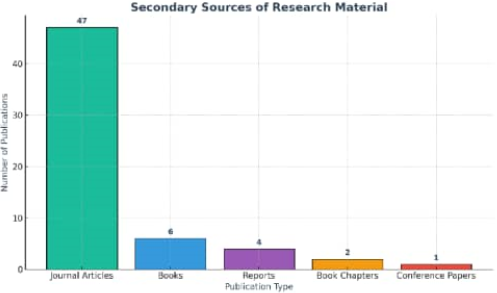

To ensure transparency, repeatability, and thoroughness in sourcing and synthesizing documentation, this research applies PRISMA's structured four-phase process: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion to identify reports from reputable institutions, textbooks and articles from major databases of peer-reviewed articles, including PubMed, Google Scholar, and specific sites for legal documentation. Collectively, this methodology facilitates a systematic analysis of laws and policies to identify gaps, conflicts, and opportunities for harmonization. Hence, data obtained from the primary sources are presented in a diagrammatic or chart flow in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Primary Research Material in the EAC Region and Selected Countries on mHealth

Figure 2. References from various secondary sources of Research Material

The use of a doctrinal PRISMA approach in this study is both intentional and methodologically strategic, as it allows for a structured and evidence-based analysis of digital health governance in East Africa. Comparatively, at the doctrinal level, the study examines the legal and public health frameworks of Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania, as well as the relevant regional instruments of the East African Community (EAC), to identify areas of agreement, disparity, and incoherence in regulation. This approach enables the study to move beyond a mere listing and description of laws to a more profound interpretive analysis of how legal norms actually function in practice. By identifying overlaps, gaps, and inconsistencies across various jurisdictions, the research illustrates how incomplete and overlapping governance structures could be obstacles to the effective regulation of mHealth interventions, especially in an area where digital health solutions are often employed across national borders.

The doctrinal analysis, in its essence, provides a thorough critique of laws, court rulings, policy measures and regulatory directions to judge if the legal framework is sufficient to handle the fundamental digital health issues such as data privacy and protection, transborder data traffic, interoperability, ethical control of health data, and supervision of mHealth technologies by the institutions. The use of the PRISMA Guide not only helps but also assures that the study will be transparent, reproducible, and analytically rigorous in the process of identifying and selecting the most credible legal materials. Moreover, PRISMA will play an important role in advocating for the relevance of the research by anchoring legal interpretation in systematically reviewed evidence, thus allowing the construction of a coherent legal argument for harmonized regional governance and the enactment of targeted legal reforms. Consequently, the integration of the doctrinal and PRISMA approaches will enable this research to come up with a sustainable and legally sound mHealth integration roadmap that not only protects the public health and the region's legal harmony in East Africa but also fosters innovation.

- RESULT AND DISCUSSION

- Conceptual Discussion and Integration of MHealth Technologies in Public Health Care

While technology is often said to transcend boundaries seamlessly, integrating technology into health care crosses the walls of hospitals and reaches the hearts of communities [43]. Hence, the idea of mobile health (mHealth) is considered an intersection of technology and the health care delivery system [44]. mHealth refers to the use of mobile and digital devices or gadgets to facilitate medical and public health care delivery [45]. It is part of eHealth, specifically and explicitly focused on mobile devices such as tablets, sensors, and wearable devices [46]. These devices could be relied on to collect, analyses, and distribute health information concerning a patient or intending patient [47]. In East Africa, mHealth is viewed as an example of an innovative response to persistent issues of weak health infrastructure [48], a scarcity of health personnel, and effective management of health data [49]. Furthermore, it is also a means of rebranding the health sector to meet global standards of the healthcare system. However, it should be noted that the implementation of mHealth technologies within East Africa is also driven by national agendas [50]. In Uganda, for instance, the mTrac platform has been utilized by healthcare providers to send SMS reports of essential and relevant medicines that are out of stock, disease surveillance data, maternal health information and several healthcare deliveries [51]. Hence, over the years, real-time reporting in Uganda has improved the capacity of the Ministry of Health to respond and make informed decisions and ensure accountability [52]. In Kenya, mobile health projects, such as M-TIBA (Mobile-Telephone Health Wallet), are changing how citizens access healthcare and pay for health services [53]. Furthermore, M-TIBA has also aided in increasing affordability and accountability in healthcare delivery [54]. Another example in Tanzania is the Wazazi Nipendeni (Love Me, Parents) initiative that utilizes SMS and social media to engage mothers in sharing vital maternal and child health information, creating awareness and preparations for maternal deliveries.

Furthermore, the mHealth technologies in East Africa can be categorized in several different ways based on their applications, aims and goals [55]. The most prevalent type of mHealth initiative includes mobile communication and messaging systems, or SMS and voice services, that distribute health education information, reminders, and awareness campaigns, for example, family planning, HIV prevention, or vaccination alerts. The health monitoring systems, especially those delivered through a smart wearable platform, allow health professionals to monitor the vital signs of patients or conditions of chronic diseases (for example, diabetes or hypertension) in a continuous way in order to manage the health professionally [56]. Application-based data collection and reporting, for example, mTrac in Uganda, are often used as tools in the continent’s interventions to eradicate disease, while also supporting supply chain management and epidemiological studies. Finally, mobile financing platforms, such as M-TIBA in Kenya, support health financing, insurance, and ultimately provide potential avenues for financial inclusion. However, the most advanced digital health technology system is the telemedicine application [57]. It allows healthcare service providers and patients to connect via video call or chat applications to reduce the burden on urban medical facilities and connect rural populations to health specialists. This form of health technology is yet to be fully achieved within the East African Community.

Integrating the mHealth into the East African public health system frameworks requires aligning laws and public health ethical guidelines as they concern digital health innovation. mHealth systems have increasingly been understood and are becoming a major concern of governments as one strategy to improve and rebrand national health policy goals and contribute to national agendas [58]. For example, in Uganda, the Digital Health Strategy (2023-2027) is considered to fully include the mHealth system as part of the overall health information system, while in Kenya, Digital Health is emphasized in the 2016 to 20230 National eHealth Policy with strategies to implement digital health principles that recognize the interoperability of infrastructure and healthcare data protection. Finally, in Tanzania, the Digital Health Investment Road Map (2017-2023) seeks coordination among stakeholders in the MHealth sector to support public health goals for wider health coverage. Each of these frameworks highlights the region’s shift from piloted or pre-testing digital health projects to more institutionalized and systematic efforts to design and develop digital health systems [59].

In relation to this, the conceptual and practical integration of mHealth technologies in East Africa represents an impactful progression of modernizing public health care delivery [60]. Hence, mHealth enhancements preventive care, enables prompt diagnoses and offers equitable access to healthcare deliveries. Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya show how context-driven adoption of digital health tools can address healthcare gaps, amplify patient engagement and provide data-based decision-making. As the region continues to align digital health policy and infrastructure, mHealth can shift health systems from reactive to proactive, hospital-centered to community-oriented service, and ultimately from fragmented to integrated. Nonetheless, significant integration of mHealth technology will rely on the effective legal framework, regulation, governance and a harmonized legal framework within the East African Community.

- Legal and Public Health Framework concerning MHealth Technologies in East Africa

East Africa is considered one of the sub-regional bodies that is fast-growing in digital technology transformation in virtually all sectors. Hence, in healthcare delivery, they have witnessed tremendous development and transformation in the treatment, diagnosis and monitoring of patient health. However, as the East African Community continue to witness digital innovation in their health sector, there is a growing demand for a robust health law and health framework to integrate an mHealth guide for effective regulation and service delivery within countries in East Africa. Furthermore, for transborder coordination and regulation, it is also required that there is a need for a unified and binding treaty on mHealth technology. Hence, it will be relevant to consider the East African Legal Framework and selected countries within the East African Community as it concerns mHealth technology.

- East Africa Regional Laws

The East African Community (EAC) has recognized digital health, particularly mobile health (mHealth), as one of the key enablers of health integration in the region and beyond mere excitement for a one-off collection of disconnected national initiatives. The EAC Regional Health Sector Strategic Plan (2024-2030) acknowledges digital transformation as a key thematic area for health integration in the context of common governance, interoperability of health information systems, and coordinated emergency communications and infectious disease surveillance across Partner States. The EAC vision for digital health is accomplished through three high-level instruments. First, the EAC Regional Health Sector Strategic Plan outlines the policy framework for a common health architecture and cross-border data exchange, including risk-and-crisis communications. Second, the EAC Digital REACH Initiative, which is jointly developed under the auspices of the EAC and the East African Health Research Commission, complements this policy and is the operative vision definition, including the definition of technical standards, interoperability roadmaps, frameworks for telemedicine, technical coordination, and common regional digital health services. All of these regional frameworks are internationally positioned and conform to the normative guidelines of the World Health Organization Global Strategy on Digital Health (2020-2025), which outlines normative guidelines for governance, privacy, security, equity, and evaluation, among others, so the EAC digital health systems conform to international best practices.

These instruments are critical to mHealth in East Africa because they enable the region to transition from isolated national digital-health pilot projects to a united regional ecosystem (that is, standards-based), which in turn will be able to rapidly scale safely and equitably for the region at large. Both the EAC strategy and Digital REACH have placed high importance on establishing shared interoperability layers that enable mobile apps, telemedicine platforms, and health information systems to rely on common data standards and harmonized governance frameworks. This will allow them to share aggregated surveillance data, facilitate cross-border referrals, respond to emergencies, and use some of the same clinical decision-support tools for care. Additionally, the WHO framework reinforces the need for data-governance protections, including privacy, consent, cybersecurity, and rigorous monitoring and evaluation. Therefore, mHealth implementers need to be prepared to address the technical and ethical considerations of the framework. Thus, going forward on the regional agenda, there will be immediate legal and operational grantees; harmonizing national approaches to data-protection and cross-border data-sharing; developing common standards; aligning telecom, health-records and privacy laws with regional interoperability frameworks; and investing in institutional capacity. The coordinated approach to respond to these is essential to avoid fragmented systems at the National level and for mHealth solutions to systematically upscale and unpack safely and without compromising legitimacy across East Africa.

- Uganda Legal Framework

In Uganda, there are several laws that have been adopted to address the peculiarity of regulating digital technology and incorporating digital technology into their healthcare system. Hence, the regulation of mHealth in Uganda through digital technology laws aims to ensure there is a balance of innovation and as well as securing the rights of its citizens towards the use and reliance on mHealth. Some of these notable laws in Uganda include the Data Protection and Privacy Act of Uganda 2019. This legislation addresses sensitive information such as the collection of patent data or information, processing, transfer and storage of relevant health. In this regard, sections 12 and 13 of the acts seem to guide the Healthcare system utilizing mHealth technology on manners and ways to obtain information from data subject or their patient willing to utilize the mHealth technology facility. Section 12 stipulates that an individual who obtains personal data from a data subject must do so lawfully, and the data must be used for the specific purpose the data subject was informed. Furthermore, section 13 mandates a compulsory briefing of the data subject concerning relevant information before their personal data can be obtained from them. This information includes;

- The nature of data to be collected

- Information of the data collector, such as name and address

- Essence for collecting the data

- Identifying or informing the data subject of their discretionary rights or mandatory supply of the data

- Whether it is a legal obligation or authorised by law to collect the data

- Implication for refusal to supply information by the data subject

The above is aimed at ensuring transparency and a build-up of confidentiality when dealing with the data subject in the process of obtaining their personal data. Also, section 3(b) stipulates that where personal information is collected, the collector shall deal with the information lawfully and fairly without infringement. Section 9 of the act requires that consent of the data owner be obtained before it can be processed or disclosed to a third party, except on the following legal grounds as provided for by section 7:

- Where there is a legal directive or obligation to investigate an issue or crime

- Where there is a need for disclosure based on public policies

- The data subject had placed his/her data in public

- The data is already in the public domain

Furthermore, a cursory review of section 20 of the Data Protection and Privacy Act of Uganda stipulates that data relating to health is considered very sensitive. Hence, an adequate standard of care and security should be employed to protect it from infringement. These can be done through placing restrictions on access to the data and through encryption. Furthermore, through the Act, the Uganda National Information Technology Authority was empowered to ensure effective compliance and enforcement. Concerning this, it suffices to state that the integration and operation of mHealth in Uganda must ensure it is operating within the bounds of law. Which, in essence, means health providers utilizing mHealth must obtain patient consent to utilize their data in the mobile health technology and ensure that the essence of the data collection is used for the stipulated purpose. Furthermore, they are also required to utilize secure encryption to avoid hackers or internet fraudsters hacking or having access to the data for fraudulent purposes.

This is concerning the fact that, as an operator or owner of mHealth, they could be held liable for data infringement if a third-party fraudster has access to the data through their mHealth gadget. This is as provided in article 3 (a)(b)(f) and (g) of the Uganda Data Protection Act, which stipulate that any person or institution that collects, controls and processes data must ensure adequate security of data, deal fairly, lawfully and transparently with the data in their custody. It further stipulates that any violation of the data, the controller or the collector or the process, as the case may be, will be held responsible. Furthermore, section 10 further stipulates that a data collector should make use of data belonging to a data subject in a manner that infringe their rights. This absolute red flag and a warning for healthcare delivery institutions that operate through mHealth technology to take into consideration when dealing with health data.

The Computer Misuse Act (CMA) is another notable and reliable Ugandan laws that provide relevant provisions that regulate mHealth. Some of these provisions of the legislation tend to prohibit and criminalize the alteration, access and disclosure of personal data without the consent or authorization of the data subject. Section 2 of the CMA defines a computer to include a magnetic, electronic devices that process data, perform arithmetic and stores information. Concerning this, it suffices to state that most of the gadgets used in mHealth qualify and fit within the context of section 2 of CMA as a computer. Hence, all provisions that concern the Computer Misuse Act are considered applicable to mHealth digital technology practice in Uganda. Furthermore, section 5 of the CMA stipulates that a person who may have access to data in a computer includes an individual who is authorized to control the access to a computer and individual has obtained consent to access data from the computer. In this regard, sections 12 and 14 of the CMA prohibit unauthorized access and modification of data in a computer by interfering with the computer to alter, destroy, or sell data. Section 13 of the CMA further stipulates that a violation of sections 12 and 14 of the CMA with the intent to commit a crime is an offence.

Other acts that constitute an offence in dealing unfairly with a computer and health data within the computer gadget are as provided for section 15 of CMA which provides for the prohibition of interception of service delivery through an authorized access to a computer, section 16 of CMA, which deals with obstruction of computer usage in healthcare delivery and section 17 of the CMA that deals with the unauthorize disclosure of computer access code. Anyone who engages in any of these acts identified in sections 15, 16 and 17 of the CMA is considered to have committed an offence. Furthermore, the incidence of internet fraudsters has become a common global issue; hence, because mHealth could be subject to committing internet fraud, Article 19 of the CMA prohibits any act of deliberate deception perpetrated to defraud or commit fraud through fraudulent obtaining data from a computer or manipulating a computer to commit fraud. It further stipulates that anyone found guilty will be liable to pay a fine or imprisonment for a period of fifteen (15). As part of the penalty, section 28 of the CMA empowers the relevant authority to search a premises and seize a computer gadget used to commit or violation of the provisions of the Computer Misuse Act.

Also, there are other relevant Uganda legislation that is of relevance to mHealth regulation and governance. This legislation includes the Electronic Signature Act (ESA), which was enacted in 2011. This law permits the use of an e-signature as stipulated in sections 3 and 4 of the ESA. However, section 15 of the ESA seems to stipulate that a recipient of a digital signature can decide to reject or accept on the grounds that there is a reasonable ground to believe that the signature has been forged. Furthermore, the provision also requires the rejecting recipient to immediately inform the signer based on the grounds of rejection. This, in essence, authenticates patient e-signature through mHealth and Doctor Prescription with their e-signature within mHealth. While the Access to Information Act provides the right to have information or collect data that is within the government's guidance and domain, except where it is considered that it will prejudice National security. Furthermore, the Electronic Transaction Act, which was enacted in 2011, also seem to be more relevant to mHealth regulation. This is concerning the fact that Article 7 of the Electronic Transaction Act (ETA) stipulates that the fact that a communication or transaction is done online shall not be invalidated or declared not legally binding. In this regard, by sections 5 and 8 of the Electronic Transaction Act, it is considered a transaction or agreement through online or electronic means binding. Hence, the Electronic Transaction Act solidify and legalizes any communication or agreement between the patient and mHealth provider as binding and legally recognized.

Concerning the above, it suffices to state that mHealth technology governance seems to be adequately provided for in the Computer Misuse Act, Data Protection Act, and other relevant legislation and policy. Most especially on the part of data protection and security. This, in essence, encourages and ensures a seamless integration of digital mobile technology in enhancing the health care system in Uganda.

- Kenyan Legal Framework

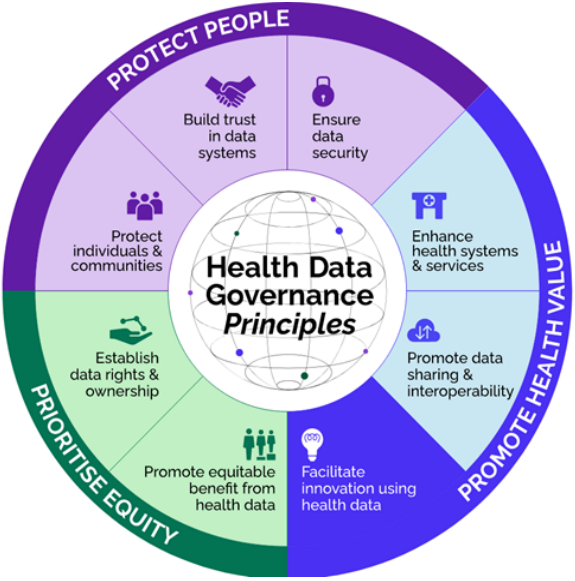

In Kenya, several laws provide for the application of digital technologies in the health care system. These laws and policies concerning mHealth are therefore informed by the Legislative Guide on Digital Health Technologies and Data in Kenya. This guide could be better summed up based on the diagrammatic in Figure 3. The Data Governance on Health Principles Diagram above is as presented in the Legislative Guide on Digital Health Technologies and Data Protection of Kenya, it provides a general framework and guide for enabling responsible, equitable and secure data use in health data ecosystems. It outlines three high-level goals: Protect People, Promote Health Value and Priorities Equity, which are the foundation of the governance principles. Under the Protect People pillar, the framework encourages public trust in data systems, committing to secure data systems, as well as protecting individuals and communities. The Promote Health Value principle is framed around building health systems and services, encourages data sharing and interoperability, and increases innovation through the use of data for a benefit. The Priorities Equity pillar charges equity in rights, ownership, and equitable benefits of health data, fair participation across populations, and so forth. Each of the Health Data Wayfinding Principles supports a rights-based and inclusive approach to digital health governance in Kenya, while balancing innovation with privacy, accountability, and social justice. Hence, this guide serves as support and a booster to legislation as it concerns digital technology application in mHealth. Concerning this, some of these laws will be examined as follows.

Figure 3. Health Data Governance Guide

Within the East African Community, Kenya also stands out as one of the countries that is advancing and developing in their health through the gradual integration of mHealth. Hence, several of its legislations are further geared towards addressing some of the peculiar issues (such as data governance in general) that may arise as it concerns mHealth. One of Kenya's notable legislations includes the Data Protection Act of No. 24, which came into effect in 2019. Section 18(1) of the Kenya DPA prohibits anyone from acting as a data processor or controller except for fulfilling the condition of registration. Hence, Section 18(2) empowers the data commissioner to register any person who intends to act as a data processor, collector and controller upon meeting the following conditions:

- The nature or type of Industry the intending party operate

- Volume or number of data intended to be obtained or processed

- Identification of the sensitive nature of the data

- Other relevant conditions as may be determined by the data commissioner

Concerning this, section 19 further requires the applicant to provide a proper description of the data subject, purpose for obtaining the data and any other relevant information that could be used to facilitate the registration. Also, section 19(2)(e) and (f) stipulate that the applicant for data controller registration must demonstrate a proper description of dealing with data and data subjects, and possible security mechanisms and measures have been put in place in addressing these challenges. Also, provide indemnity in the case of violating the data subject rights. Upon meeting this condition, the data commissioner is mandated to issue a certificate of registration. Section 20 of the DPA further stipulates that the certificate issued is for a period of time, which will require renewal for the data controller to operate legitimately. However, by section 22 of DPA, the commissioner is empowered to cancel already issued certificate of registration where the information provided is false or misleading or there is a failure in compliance with the provisions of DPA. Concerning this, it suffices to state that the DPA seem to address the issues that an mHealth provider can only operate upon meeting the conditions of sections 18 to 22. Hence, this process tends to legitimately ensure that mHealth provider operations within Kenya are legally recognized and regulated. Hence, citizens of Kenya are also well-protected individuals who may have a hidden agenda to commit a crime.

However, it suffices to state that where an industry has been certified by the data commissioner as a data processor or collector for a specified purpose, the DPA further stipulate procedures or principles concerning the collection and safeguarding of data obtained from the data subject. Hence, the section stipulates that the data processor must obtain data directly from the data subject. Which, in essence, further qualified sections 29 and 30 of the DPA of Kenya, which stipulate that the data processor must seek the consent of the data subject before obtaining their personal data. However, section 28(2) of DPA further stipulates that data may be obtained indirectly from a public record, where the data has been in the public domain by the data subject, obtaining the consent of the data subject to obtain the data from other sources. Furthermore, data could also be obtained indirectly from a guardian for investigation, national security and law enforcement. Furthermore, the issues of consent also extend to address or prohibit a data controller from commercial use of data without the consent of the data subject, as stipulated by section 37. Hence, mHealth technology providers are required to comply with this process of obtaining data to avoid violation of the rights of data subjects. Also, the data controller is further placed under strict rules in ensuring the data is well safeguarded and protected. This is concerning the fact that section 25 of the DPA stipulates that data obtained shall be used fairly and lawfully for the sole purpose it was collected. The data controller must ensure to safeguard and avoid incidents that may result in the violation of the data subject's rights. Hence, section 31 of the DPA stipulates that a data controller should carry out a data impact assessment to ascertain circumstances that are likely to result in a high risk of violating data subject rights. Hence, where a risk is identified, it requires the data controller to take adequate security measures to avert the risk or prevent the risk. In this regard by these provisions, mHealth provider are required to ensure that their platform does not become an instrument for fraudulent activities.

However, the DPA identify health data as a very sensitive data that should not be processed except under strict circumstances. Section 46 of the DPA stipulates that a data processor shall not process health personal data except within the health sector or authorized by law. Furthermore, section 46(2) further stipulates that health data can be processed where it is necessary to safeguard public interest. Hence, this does not in any circumstances mean that a private mHealth provider qualifies under these provisions. It is mainly for public healthcare providers or those authorized by law. Hence, where a private mHealth care provider is dealing with sensitive health data, section 44 of the DPA stipulates that such data must be processed in accordance with section 25 of the DPA, which requires fair and lawful dealing with data, avoiding acts that violate the rights of the data subject.

Also relevant in this regard is the Health Act No. 21, which came into effect in 2017 and ODPC's Guide for Health Data processing. While the Health Act is considered a primary health law that regulates the health sector in Kenya, however addresses issues as they concern mHealth. This is concerning the fact that the Act requires that patient information be treated confidentially. Hence, this information could be interpreted to include patient data obtained and stored electronically or through a digital technology platform such as mHealth. Furthermore, the cabinet secretary is mandated to issue regulations or directives on the use of digital technology towards an effective health delivery that is based on patient safety and ethical delivery. Also, the ODPC Guide on Health Data Processing stipulate guide on how to incorporate the Kenya Data Protection Act into digital technology to enhance health care, like the mHealth. Hence, the guide further requires the mHealth provider and its developer to ensure maximum security of health data through encryption and constant auditing. In this regard, it suffices to state that this process contemplated by the guide could aid in stemming or curtailing the incidence of misuse of data and fraudulent activities.

Concerning the above, it is apt to state that Kenya has robust laws and policies as it concerns digital technology to enhance the healthcare system. Hence, mHealth, which falls within this category is can also be regulated by these laws and policies. Although there are several shortcomings which may or like limit and have an impact on the integration of mHealth.

- Tanzanian Legal Framework

The regulatory framework of digital technology enhances the health care system in Tanzania is encompassing. This is concerning the fact that it has both a binding and policy framework that does not integrate digital technology health systems like mHealth, but also serves as a regulatory framework and governance. Hence, it will be relevant to examine some of these laws as they concern the integration and regulation of mHealth in Tanzania. One of their notable laws is the Tanzanian National Digital Health Strategy, which was contemplated and adopted in 2019. This strategic guide was meant to advance more on the National Health Strategic Guide of Tanzania in 2013. This guide provides a strategic measure through which ICT could be integrated and utilized within the Tanzanian healthcare system. Hence, the guide seeks to deploy and promote digital technology to enhance health, such as mHealth, in major rural parts of Kenya as a way of addressing access and affordability of quality healthcare challenges. Another notable innovation introduced by the guide is that it requires healthcare systems utilizing sophisticated systems such as mHealth to ensure standardized and secure data and electronic records. However, this guide is considering a mere soft law that merely directs but is not binding or possesses the force of law sufficient to regulate and govern mHealth in Tanzania.

However, there are other legislations dedicated to addressing data and privacy concerns in utilizing digital technology and electronic systems such as mHealth. The Tanzanian Personal Data Protection Act of No. 11 (PDPA), which came into effect in 2022, is considered relevant in this regard as it concerns mHealth regulation and governance. The preamble of the PDPA interprets a data controller as those who obtain or are in possession of personal data of a data subject with the main aim of utilizing it for a specific purpose that is within the knowledge of the data subject. However, not everyone qualifies or can be addressed as a data controller except such an individual or institution meets the criteria of registration as stipulated by the PDP Act. Hence, section 14, no person or institution shall act as a data controller in obtaining data without a formal registration with the commission. Hence, upon application to the commission for certification in obtaining data, the commission shall decide whether to issue the certificate or reject the application. Section 15 empowers the commission to maintain a register of those acting as data controllers and processors within Tanzania. By section 16, the certificate issued upon registration will only last for a period of 5 years, and it is renewable.

However, a cursory review of these provisions reveals that the conditions upon which a commission may grant certification or rejection of an application were not provided for by the PDP Act. This in essence, creates a discretionary and blanket power for the commission, which could become subject to abuse. Furthermore, it also creates ambiguity and confusion for individuals and institutions regarding the actual requirements for registration. However, one relevant and cogent aspect of the PDP Act is section 5, which appears to require data controllers and data processors to deal with the data obtained fairly, lawfully, and in a transparent manner. It also stipulates that data obtained from a data subject should be solely used for the legitimate purpose for which it was obtained. To ensure data controllers and processors comply with this provision, sections 6 and 7 of the PDP Act created the Personal Data Protection Commission, with its major functions of ensuring due compliance with the provisions of the act and preventing the breach of personal data of a data subject. Hence, it suffices to state that an mHealth care provider can be categorized as a data controller and processor, which in essence are bound to comply with the provisions of the PDP Act.

The Electronic and Postal Communications Act (EPOCA), Cap. 306 provides regulatory oversight to the electronic communications sector, which serves as the technological mainstay for mHealth configurations. In Section 165, EPOCA grants the Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority (TCRA) the authority to ensure that all electronic communications, including electronic communications of health data, are secure and confidential. Therefore, mHealth setups must ensure compliance with the technical and licensing requirements as outlined by TCRA requirements, particularly within the arrangements for the transmission of data over mobile networks. The combination of EPOCA and PDPA will ensure that the technological and legal dimensions of digital health are adequately regulated.

- Legal and Public Health Governance Challenges in Integrating MHealth Technologies

Where technology is fast-growing but the law is slow, it is bound to result in things falling apart, thereby posing regulatory challenges. This is a clear depiction of the leading obstacle to mHealth technologies in the legal and public health environments of the East African Community (EAC). The following serves as a challenge.

- Fragmented Legal Frameworks

While the EAC’s Regional Health Sector Strategic Plan (2024–2030) and the Digital REACH Initiative offer ambitious frameworks for interoperability and jointly regulated governance, the region faces disparate, inconsistent national legislation and a lack of binding, harmonized law. Hence, it suffices to state that the EAC does have a binding legal framework to support harmonized frameworks standards and data shares protocols: however, these frameworks are employed differently depending on the context of the member-state; for example, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, etc., which vary widely on their level of their data protection laws and their enforcement is exceptionally dependent upon both the relevant legislation, plus the digitization of their health systems. These dynamic differences complicate regional interoperability and lawful exchanges of health data between countries, which are among the core conditions for sovereignty in country-level surveillance or digital technology health practice, not to mention mobile health platforms. Furthermore, most of the region’s agreements are focused on policy and not legally binding (treaty binding), which raises more concerns for mHealth developers and their ability to operate within multiple jurisdictions. Consequently, due to the lack of regional harmonized legislation in digital health, mHealth developers are often left in a circular case of legal uncertainty and overlapping mandates, specifically with respect to accountability and the legality of transferring data.

- Enforcement Gaps

At the national level, Uganda and Kenya have adopted separate data protection laws: the Data Protection and Privacy Act and the Data Protection Act, respectively. While enforcement remains in its infancy, it could give room for exploitation and fraudulent activities. Furthermore, where there is lack of effective enforcement, it could also result in a lack of general public awareness of their data privacy rights and compliance with mHealth platforms registration as stipulated by laws. None of these weaknesses will provide patients protection from potential risks of data breaches, undesired commercialization of data, or abuse of their personal health information by third parties. Furthermore, the broader public health question involves bringing the legal system in line with ethical, technical, and infrastructural realities. For the most part, East African health systems are still operating with donor-funded digital health initiatives that do not function under formal government auspices, continue to create data silos, and result in fragmented governance. The lack of infrastructure could result in additional challenges with rural connectivity, low digital literacy and an inadequate cybersecurity infrastructure, increasing vulnerability to mHealth adoption. Furthermore, while frameworks like Kenya's Health Data Governance Principles mention values such as equity, trust, and innovation, sustaining them into operationalization requires sustained investment and political will to support local digital infrastructure, workforce enhancement, and citizen engagement. Coordination of cross-border operations between the EAC states is also necessary for disease surveillance, data sharing, and telemedicine, but it also lacks primary data sharing guidelines among members regarding mutual recognition of standards and digital adequacy in data protection. Moving to operational harmonization from policy is fundamental; such capacity must be built to enforce the policies, further develop regional agreements for data sharing, and progressively extend the legal frameworks with technological innovation. All of this is necessary to support health outcomes and human rights in East Africa.

- Socio-Economic and Infrastructural Barriers

However, other relevant socio-economic challenges include the issue of privacy and cybersecurity threats, and resistance of traditional medical institutions and providers. Though the increasingly high risks of data breaches, exposure and cyberattacks in the East African digital health ecosystem is due to the lack of encryption, weak cybersecurity infrastructure, and low awareness by users and providers. In addition, traditional medical institutions and providers continue to resist mHealth as they have concerns about losing their profession, services offered to patients creating confidentiality issues, as well as not having clarification on regulating standards. For many practitioners, the idea of using mobile-based consultations, mHealth or AI-assisted diagnostics is perceived to violate conventional medical ethics and put practitioners' jobs and roles at risk. Hence, all these challenges are going to require regional harmonized standards, investment in the use of technology and improved cybersecurity and the capacity of institutions involved with digital health initiatives, and continuous engagement of the different stakeholders involved or impacted by national and regional digital health policies.

- CONCLUSIONS

This study considers mHealth as one of the main pathways for future healthcare in East Africa, but its success will depend mainly on the harmonization of the legal and public health frameworks. Utilizing a comparative doctrinal-PRISMA approach, the article not only proposes a theoretical contribution by characterizing harmonized digital health governance as the essential link among innovation, patient rights, and regional integration but also claims that. Furthermore, it is evident from the results that, irrespective of Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, and the EAC taking up some sort of legal protection for data, ethical medical practice, and inter-country collaboration, the problems related to weak enforcement, lack of institutional capacity, and regulatory inconsistencies are still hindering progress. These findings imply that they show technological readiness by itself is not enough; strong and coordinated legal frameworks are crucial for the continuous adoption of mHealth solutions.

The study, although having its merits, is still limited in that it primarily relies on doctrinal sources, which do not allow the empirical assessment of mHealth laws’ practical application. Because the study aims to examine the sufficiency and existing laws as they concern MHealth in East Africa. Future research should use empirical methods, stakeholder interviews, and impact evaluations to measure the effectiveness of the regulation at the community and clinical levels. That is when the laws are being updated to address the current trend of MHealth. Moreover, new studies can investigate such areas as the adherence of private-sector companies to the laws, the adoption of cybersecurity measures, and the engagement of new technologies like AI in the digital health domain. Furthermore, the study offers a novel view by unravelling the interconnectedness of legal harmonization, public health governance, and mHealth sustainability in the context of an African region via a systematic approach. Its delineation of clear normative and policy routes gives a grounding for reforms which would be directed towards the development of equitable, safe, and ethically controlled digital health systems in East Africa. Hence, the following are therefore recommended:

- In remedying the observable governance barriers of mHealth technologies, it is essential to take an integrated multilevel response to promote legal and institutional support in East Africa and its governance frameworks.

- The East Africa Community need to pursue harmonisation of data governance standards, improved coordination among government ministries and regulatory agencies, and the necessary regulatory frameworks, governance, and standards for emerging technologies such as mHealth.

- It will require governments to continue investing in financial sustainability for digital health programs, by including them in health budgets rather than relying on donors, which in many cases delays mHealth uptake in support of local governments and countries.

- Assisting with harmonizing all data sharing standards and interoperability frameworks across the East African Community will also allow for low-risk sharing of health information on a trans-border basis.

- Building robustness to cybersecurity infrastructure, presenting existing policies and improving digital literacy skills for health workers and consumers assists on privacy issues.

- Improve capacity building initiatives, builds on the technical and regulatory legs of public institutions governing mHealth engagement.

- Finally, public and private partnerships will significantly spur motivation and accountability while building trust across the system guideline of the mHealth.

DECLARATION

Author Contribution

All authors contributed equally to the main contributor to this paper. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Funding

The author did not receive any funding for this research

Acknowledgement

The author thanks their respective institution for providing the enabling environment for research activities. Furthermore, the author also appreciates the Chief Editor and management of Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro for their classic editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- K. Ndlovu, M. Mars, and R. E. Scott, “Development of a conceptual framework for linking mHealth applications to eRecord systems in Botswana,” BMC Health Services Research, vol. 21, no. 1, p. 1103, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-07134-4.

- L. Wallis, P. Blessing, M. Dalwai, and S. D. Shin, “Integrating mHealth at point of care in low- and middle-income settings: The system perspective,” Global Health Action, vol. 10, no. sup3, p. 1327686, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2017.1327686.

- K. Harding et al., “A mobile health model supporting Ethiopia’s eHealth strategy,” Digital Medicine, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 54–65, 2018, https://doi.org/10.4103/digm.digm1018.

- K. M. Emmanuel, “Impact of technology on global health initiatives,” Sciences (NIJRMS), vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 66–73, 2025, https://doi.org/10.59298/NIJRMS/2025/6.2.6673.

- K. Ndlovu, R. E. Scott, and M. Mars, “Interoperability opportunities and challenges in linking mHealth applications and eRecord systems: Botswana as an exemplar,” BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, vol. 21, no. 1, p. 246, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-021-01606-7.

- S. Africa, Top Up Your Healthcare Access. Financializations of Development: Global Games and Local Experiments. 2023. https://books.google.co.id/books?hl=id&lr=&id=EjexEAAAQBAJ.

- N. S. Mohta, E. Prewitt, L. Gordon, and T. H. Lee, “The Macro Trends Driving Care Delivery,” NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery, vol. 5, no. 5, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1056/CAT.24.0159.

- K. G. Mugalula, “Regulation of artificial intelligence in Uganda’s healthcare: exploring an appropriate regulatory approach and framework to deliver universal health coverage,” International Journal for Equity in Health, vol. 24, no. 1, p. 158, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-025-02513-3.

- B. Clough, Challenging the frames of healthcare law. Embracing Vulnerability: The Challenges and Implications for Law. 2020. https://books.google.co.id/books?hl=id&lr=&id=y-_QDwAAQBAJ.

- M. Njoroge, D. Zurovac, E. A. A. Ogara, J. Chuma, and D. Kirigia, “Assessing the feasibility of eHealth and mHealth: A systematic review and analysis of initiatives implemented in Kenya,” BMC Research Notes, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 90, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2416-0.

- W. K. Kansiime et al., “Barriers and benefits of mHealth for community health workers in integrated community case management of childhood diseases in Banda Parish, Kampala, Uganda: A cross-sectional study,” BMC Primary Care, vol. 25, no. 1, p. 173, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02430-4.

- S. Mburu and O. Kamau, “Framework for development and implementation of digital health policies to accelerate the attainment of sustainable development goals: Case of Kenya eHealth Policy (2016–2030),” Journal of Health Informatics in Africa, vol. 5, no. 2, 2018, https://doi.org/10.12856/JHIA-2018-v5-i2-210.

- K. Perehudoff, “Universal access to essential medicines as part of the right to health: a cross-national comparison of national laws, medicines policies, and health system indicators,” Global Health Action, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 1699342, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2019.1699342.

- E. C. Fuse Brown, A. S. Kesselheim, D. Malina, G. Pittman, and S. Morrissey, “Fundamentals of Health Law—a new perspective series,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 387, no. 4, pp. 372-373, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe2207887.

- S. Till et al., “Digital health technologies for maternal and child health in Africa and other low- and middle-income countries: Cross-disciplinary scoping review with stakeholder consultation,” Journal of Medical Internet Research, vol. 25, p. e42161, 2023, https://doi.org/10.2196/42161.

- V. M. Kiberu, M. Mars, and R. E. Scott, “Barriers and opportunities to implementation of sustainable e-health programmes in Uganda: A literature review,” African Journal of Primary Health Care and Family Medicine, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–10, 2017, https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v9i1.1277.

- P. A. Aidonojie, J. Nwazi, and U. Eruteya, “The legality, prospect, and challenges of adopting automated personal income tax by states in Nigeria: A facile study of Edo State,” Cogito, vol. 14, no. 2, 2022, https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=1060583.

- World Health Organization. Universal health coverage partnership annual report 2022: More than 10 years of experiences to orient health systems towards primary health care. World Health Organization. 2024. https://books.google.co.id/books?hl=id&lr=&id=d_cXEQAAQBAJ.

- I. Iyamu, A. X. T. Xu, O. Gómez-Ramírez, A. Ablona, H. J. Chang, G. Mckee, and M. Gilbert, “Defining digital public health and the role of digitization, digitalization, and digital transformation: Scoping review,” JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, vol. 7, no. 11, p. e30399, 2021, https://doi.org/10.2196/30399.

- A. Endalamaw et al., “A scoping review of digital health technologies in multimorbidity management: mechanisms, outcomes, challenges, and strategies,” BMC Health Services Research, vol. 25, p. 382, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-025-12548-5.

- P. A. Aidonojie, O. O. Anne, and O. O. Oladele, “An empirical study of the relevance and legal challenges of an e-contract of agreement in Nigeria,” Cogito, vol. 12, no. 3, 2020, https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=1034422.

- A. A. Victor, L. J. Frank, L. E. Makubalo, A. A. Kalu, and B. Impouma, “Digital health in the African region should be integral to the health system’s strengthening,” Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Digital Health, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 425–434, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcpdig.2023.06.003.

- L. O. Gostin and B. M. Meier, Global Health Law and Policy: Ensuring Justice for a Healthier World. Oxford University Press. 2023. https://books.google.co.id/books?hl=id&lr=&id=JDXYEAAAQBAJ.

- H. W. Kohl III, T. D. Murray, and D. Salvo, Foundations of physical activity and public health. Human Kinetics. 2025. https://books.google.co.id/books?hl=id&lr=&id=HQ9PEQAAQBAJ.

- K. Ndlovu, M. Mars, and R. E. Scott, “Interoperability frameworks linking mHealth applications to electronic record systems,” BMC Health Services Research, vol. 21, no. 1, p. 459, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06473-6.

- J. McCool, R. Dobson, R. Whittaker, and C. Paton, “Mobile health (mHealth) in low- and middle-income countries,” Annual Review of Public Health, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 525–539, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-052620-093850.

- E. Rusdiana, P. A. Aidonojie, M. Jufri, H. Ismaila, and N. Ibrahim, “Augment legal efforts through artificial intelligence in curtailing economic fraud in Nigeria: Issues and challenges,” Indonesian Journal of Criminal Law Studies, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 115–148, 2025, https://doi.org/10.15294/ijcls.v10i1.22147.

- P. A. Aidonojie, N. Okuonghae, A. Najjuma, O. O. Ikpotokin, and E. Obieshi, “Legal and socio-economic challenges of e-commerce in Uganda: Balancing growth and regulation,” Trunojoyo Law Review, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1–32, 2025, https://doi.org/10.21107/tlr.v7i1.27704.

- G. E. Iyawa, S. Hamunyela, A. Peters, S. Akinsola, I. Shaanika, B. Akinmoyeje, and S. Mutelo, “Digital transformation and global health in Africa,” in Handbook of Global Health, pp. 137–167, 2021, https://doi.org/2021.10.1007/978-3-030-45009-0_6.

- A. A. Abdi, W. Guyo, and M. Moronge, “Moderating effect of mobile technology on the relationship between health systems governance and service delivery in national referral hospitals in Kenya,” European Journal of Medical and Health Research, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 18–27, 2024, https://doi.org/10.59324/ejmhr.2024.2(1).03.

- P. A. Aidonojie, E. C. Aidonojie, O. Eregbuonye, S. W. Abacha, and M. Okpoko, “Prospect, legal, and health risks in adopting the metaverse in medical practice: A case study of Nigeria,” Jurnal Hukum dan Peradilan, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 483–522, 2024, https://doi.org/10.25216/jhp.13.3.2024.483-522.

- P. A. Aidonojie, O. O. Ikubanni, N. Okuonghae, and A. I. Oyedeji, “The challenges and relevance of technology in administration of justice and human security in Nigeria: Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic,” Cogito, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 149–171, 2021, https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=1034989.

- P. A. Aidonojie, O. O. Ikubanni, and N. Okuonghae, “The prospects, challenges, and legal issues of digital banking in Nigeria,” Cogito, vol. 14, no. 3, 2022, https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=1193350.

- T. Manyazewal, Y. Woldeamanuel, H. M. Blumberg, A. Fekadu, and V. C. Marconi, “The potential use of digital health technologies in the African context: A systematic review of evidence from Ethiopia,” NPJ Digital Medicine, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 125, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-021-00487-4.

- K. Appiah, I. Sam-Epelle, and E. L. C. Osabutey, “Technology and health services marketing in Africa,” in Health Service Marketing Management in Africa, pp. 243–254, 2019, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429400858.

- P. A. Aidonojie, A. Owoche, Y. A. Aleshinloye, K. I. Maifada, and B. Resty, “The prospect, legal, and medical issues in integrating AI in medical practice in Uganda,” KIULJ, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 189–203, 2024, https://doi.org/10.59568/KIULJ-2024-6-2-10.

- A. A. Yusuf, M. Charles, M. Samuel, A. Bello, and L. Ronald, “The development and growth of AI in Uganda: How is Uganda faring from a legal perspective?,” KIULJ, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 204–223, 2024, https://doi.org/10.59568/KIULJ-2024-6-2-11.

- H. I. Adebowale, A. Mohamed, C. O. Agwu, H. Shehu, C. Magnus, D. J. John, and Y. H. N. Osman, “Intellectual property law and artificial intelligence in Uganda: Trending issues and future prospects,” KIULJ, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 224–240, 2024, https://doi.org/10.59568/KIULJ-2024-6-2-12.

- B. Odunsi, O. O. Ogancha, and O. O. Oduniyi, “Fundamental objectives and directive principles of state policy in the Nigerian Constitution: Re-examining the non-justiciability of socio-economic rights,” Journal of Indonesian Constitutional Law, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 274–298, 2025, https://doi.org/10.71239/jicl.v2i3.191.

- S. N. B. Hamdan and R. B. Nordin, “Critique against the government: Freedom of speech and expression in Malaysia,” Journal of Indonesian Constitutional Law, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 299–331, 2025, https://doi.org/10.71239/jicl.v2i3.70.

- J. N. Sekandi et al., “Ethical, legal, and sociocultural issues in the use of mobile technologies and call detail records data for public health in the East African region: Scoping review,” Interactive Journal of Medical Research, vol. 11, no. 1, e35062, 2022, https://doi.org/10.2196/35062.

- B. A. Bene et al., “Regulatory standards and guidance for the use of health apps for self-management in Sub-Saharan Africa: Scoping review,” Journal of Medical Internet Research, vol. 26, p. e49163, 2024, https://doi.org/10.2196/49163.

- B. P. Ngongo, P. Ochola, J. Ndegwa, and P. Katuse, “The technological, organizational and environmental determinants of adoption of mobile health applications (m-health) by hospitals in Kenya,” PLoS One, vol. 14, no. 12, e0225167, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225167.

- S. Lee, Y.-M. Cho, and S.-Y. Kim, “Mapping mHealth (mobile health) and mobile penetrations in sub-Saharan Africa for strategic regional collaboration in mHealth scale-up: An application of exploratory spatial analysis,” Globalization and Health, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 63, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-017-0286-9.

- T. Neumark and R. J. Prince, “Digital health in East Africa: Innovation, experimentation and the market,” Global Policy, vol. 12, pp. 65–74, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12990.

- A. O. Agbeyangi and J. M. Lukose, “Telemedicine adoption and prospects in sub-Sahara Africa: A systematic review with a focus on South Africa, Kenya, and Nigeria,” Healthcare, vol. 13, no. 7, p. 762, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070762.

- S. S. Kaboré, P. Ngangue, D. Soubeiga, A. Barro, A. H. Pilabré, N. Bationo, Y. Pafadnam, K. M. Drabo, H. Hien, and G. B. L. Savadogo, “Barriers and facilitators for the sustainability of digital health interventions in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review,” Frontiers in Digital Health, vol. 4, p. 1014375, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2022.1014375

- T. Alsamara and G. Farouk, “Legal mechanisms for digital healthcare transformation in Africa: state and perspective,” Cogent Social Sciences, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 2410363, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2024.2410363

- J. Early, C. Gonzalez, V. Gordon-Dseagu, and L. Robles-Calderon, “Use of mobile health (mHealth) technologies and interventions among community health workers globally: a scoping review,” Health Promotion Practice, vol. 20, no. 6, pp. 805–817, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839919855391.

- D. Opoku, R. Busse, and W. Quentin, “Achieving sustainability and scale-up of mobile health noncommunicable disease interventions in sub-Saharan Africa: views of policy makers in Ghana,” JMIR mHealth and uHealth, vol. 7, no. 5, p. e11497, 2019, https://doi.org/10.2196/11497.

- I. Holeman, T. P. Cookson, and C. Pagliari, “Digital technology for health sector governance in low and middle income countries: a scoping review,” Journal of Global Health, vol. 6, no. 2, p. 020408, 2016, https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.06.020408.

- R. Pankomera and D. Van Greunen, “A model for implementing sustainable mHealth applications in a resource‐constrained setting: A case of Malawi,” The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, vol. 84, no. 2, p. e12019, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1002/isd2.12019.

- O. Olu, D. Muneene, J. E. Bataringaya, M.-R. Nahimana, H. Ba, Y. Turgeon, H. C. Karamagi, and D. Dovlo, “How can digital health technologies contribute to sustainable attainment of universal health coverage in Africa? A perspective,” Frontiers in Public Health, vol. 7, p. 341, 2019, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00341.

- J. A. Namuhisa, “Political factors, sustainability and scale up of mobile health projects as early warning systems in public health surveillance in Kenya: A critical review,” International Academic Journal of Information Sciences and Project Management, vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 113–132, 2020, https://www.iajournals.org/index.php/8-articles/821-iajispm-v3-i6-113-132.

- A. Y. Mustapha et al., “Systematic review of mobile health (mHealth) applications for infectious disease surveillance in developing countries,” Methodology, vol. 66, 2018, https://doi.org/10.54660/.IJMRGE.2022.3.1.1020-1033.

- N. Al-Shorbaji, Improving Healthcare Access through Digital Health: The Use of. Healthcare Access, 315. 2022. https://books.google.co.id/books?hl=id&lr=&id=VARgEAAAQBAJ.

- D. F. Cuadros, A. Kiragga, L. Tu, S. Awad, J. M. Bwanika, and G. Musuka, “Unpacking social and digital determinants of health in Africa: a narrative review on challenges and opportunities,” MHealth, vol. 11, p. 41, 2025, https://doi.org/10.21037/mHealth-24-73.

- A. Wahbi, K. Khaddouj, H. Aziz, L. Naoufal, M. Mkik, and A. Hebaz, “Digital health transformation and decision-making in Africa,” in Proc. Int. Conf. Advances in Communication Technology and Computer Engineering, pp. 464–481, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-94620-2_41.

- L. Huisman, et al., “A digital mobile health platform increasing efficiency and transparency towards universal health coverage in low- and middle-income countries,” Digital Health, vol. 8, p. 20552076221092213, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076221092213.

- S. Latif, R. Rana, J. Qadir, A. Ali, M. A. Imran and M. S. Younis, "Mobile Health in the Developing World: Review of Literature and Lessons From a Case Study," in IEEE Access, vol. 5, pp. 11540-11556, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2710800.

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

| Dr. Paul Atagamen Aidonojie Associate Dean of Research, School of Law, Kampala International University, Kampala, Uganda Email: paul.aidonojie@kiu.ac.ug Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=list_works&hl=en&hl=en&user=VnVx2-kAAAAJ&pagesize=100 Scopus: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57221636261 |

|

|

| Dr. George Mulingi Mugabe Ashesi University, Berekuso, Ghana Email: gmugabe@ashesi.edu.gh Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?hl=en&user=YOqAxyAAAAAJ SCISPACE: https://scispace.com/authors/george-mulingi-mugabe-3ibxjqhr4s

|

|

|

| Esther Chetachukwu Aidonojie Department of Public Health, Kampala International University, Kampala, Uganda Email: chetachukwu.francis@studmc.kiu.ac.ug Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=6VKihCMAAAAJ&hl=en Scopus: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=59309720700 |

|

|

| Muwaffiq Jufri Fakultas Hukum, Universitas Trunojoyo Madura, Indonesia Email: muwaffiq.jufri@trunojoyo.ac.id Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=FiPh-i0AAAAJ&hl=en Scopus: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57357560500 |

|

|

| Dr. Mundu M. Mustafa DVC Finance and Administration, Kampala International University, Kampala, Uganda Email: mundu.mustafa@kiu.ac.ug Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?hl=en&user=-Si1QFoAAAAJ Scopus: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=8213811300

|

|

|

| Collins Ekpenisi School of Law, Kampala International University, Kampala, Uganda Email: colins.ekpensi@kiu.ac.ug Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?hl=en&user=W73sO9sAAAAJ

|

|

|

| Dr. Obieshi Eregbuonye HOD Postgraduate Studies, Faculty of Law, Edo State University, Edo State, Nigeria Email: obishi.eregbunye@edostateuniversity.edu.ng Scopus: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=59145553000 |

|

|

| Dr. Godswill Owoche Antai HOD Postgraduate Studies, School of Law, Kampala International University, Kampala, Uganda Email: godswil.owoche@kiu.ac.ug Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?hl=en&user=9szpmLIAAAAJ Scopus: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=59524441000 |

|

|

| Dr. Mercy Okpoko Faculty of Management, Law and Social Science, University of Bradford, United Kingdom, Email: okpokomercy@gmail.com Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?hl=en&user=4zyjVqAAAAAJ Scopus: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57219967471 |

|

|