ISSN: 2685-9572 Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro

Vol. 8, No. 1, February 2026, pp. 1-14

Advances in Brain-Computer Interfaces for Taste Perception: Current Insights and Future Directions

Yuri Pamungkas 1, Abdul Karim 2, Gao Yulan 3, Muhammad Nur Afnan Uda 4, Uda Hashim 5

1 Department of Medical Technology, Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember, Indonesia

2 Department of Artificial Intelligence Convergence, Hallym University, Republic of Korea

3 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Guizhou University of Engineering Science, China

4,5 Department of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Malaysia

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 13 September 2025 Revised 01 November 2025 Accepted 15 December 2025 |

|

Human taste perception is a complex multisensory process that integrates chemical, emotional, and cognitive responses within the brain. Traditional methods for evaluating taste rely on subjective reporting, which limits reproducibility and accuracy. Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) technology provides an objective solution by decoding neural activity associated with taste perception using non-invasive techniques such as EEG and fNIRS. The research contribution aims to deliver an extensive overview of the latest advancements in BCI-oriented taste research, emphasizing various applications, methodological frameworks, and potential future pathways that connect the domains of neuroscience and sensory technology. This review examines the use of EEG and fNIRS modalities for signal acquisition, preprocessing, feature extraction, and classification across 36 studies conducted between 2020 and 2025. These works employ both traditional algorithms and deep learning models, including SVM, CNNs, and Transformer-based frameworks, to decode neural signatures of basic tastes and multisensory interactions. Results show that BCIs have successfully identified distinct brain responses for sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami stimuli. They have also been applied in multisensory integration, hedonic evaluation, consumer behavior analysis, clinical diagnosis of taste disorders, and affective monitoring. However, challenges remain in signal noise, dataset standardization, and model interpretability. In conclusion, BCIs represent a promising and interdisciplinary approach for objectively studying and enhancing human taste perception through the integration of neuroscience, engineering, and artificial intelligence. |

Keywords: Brain-Computer Interface (BCI); Taste Perception; Electroencephalography (EEG); Sensory Neuroscience; Neuroengineering Applications |

Corresponding Author: Yuri Pamungkas, Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember, Surabaya, Indonesia. Email: yuri@its.ac.id |

This work is open access under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: Y. Pamungkas, A. Karim, G. Yulan, M. N. A. Uda, and U. Hashim, “Advances in Brain-Computer Interfaces for Taste Perception: Current Insights and Future Directions,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1-14, 2026, DOI: 110.12928/biste.v8i1.14718 |

- INTRODUCTION

Taste perception is one of the most complex and least understood sensory modalities in humans, integrating chemical detection, multisensory processing, and emotional evaluation within the brain [1]. Traditional methods for studying taste perception, such as sensory questionnaires, hedonic scales, or behavioral tests, heavily rely on subjective reporting [2]. These approaches, while valuable, are limited by personal bias, linguistic variability, and contextual influence [3]. Consequently, there is still a significant gap in developing objective and reproducible tools that can quantify human taste experiences directly from neural activity [4]. Understanding how the brain encodes various gustatory stimuli encompassing the five basic tastes (sweetness, saltiness, sourness, bitterness, and umami perception) remains an open scientific and engineering challenge [5].

Recent advances in neuroscience and biomedical engineering have introduced Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) as a promising solution to this problem. BCIs allow direct measurement and interpretation of brain activity through non-invasive techniques such as EEG and fNIRS [6]. These technologies can capture event-related potentials, spectral features, and hemodynamic responses associated with sensory experiences, offering a quantitative window into how the human brain perceives and evaluates taste [7]. In contrast to subjective assessment methods, BCI systems can objectively record neural correlates of taste perception, enabling researchers to decode flavor-specific brain signatures and emotional responses with increasing precision [8].

The state of the art in this field shows a growing interest in using BCIs for sensory and consumer research. Several studies have demonstrated that EEG signals can discriminate between basic flavors with classification accuracies exceeding 80% [9], and that fNIRS can detect cortical activations linked to pleasantness and taste intensity [10]. Machine learning and deep learning methods, including SVM, CNNs, and LSTM models, have been increasingly adopted to enhance the interpretability and performance of these neural decoding tasks [11]-[13]. Despite these advances, current research remains fragmented, most studies use small datasets, lack standardized protocols, and seldom integrate multimodal BCI approaches [14]. There is therefore a pressing need to consolidate existing findings and identify future directions that could strengthen methodological rigor and interdisciplinary application.

The novelty of this review lies in its comprehensive synthesis of recent developments in BCI applications specifically for human taste perception, an area that has received far less attention compared to vision, hearing, or motor control. Unlike previous works that only discuss BCIs in general sensory contexts [15], this paper focuses on the intersection of gustatory neuroscience, signal processing, and computational intelligence. It systematically examines how neural features related to taste are acquired, processed, and classified using advanced algorithms, and how these insights can be leveraged for engineering and industrial applications such as food design, sensory evaluation, and personalized nutrition.

The contribution of this research is threefold. First, it provides a structured overview of current BCI methodologies applied to taste perception, highlighting signal modalities, processing pipelines, and computational techniques. Second, it identifies major challenges (including data variability, interpretability, and scalability) that hinder real-world application. Third, it outlines future research opportunities by proposing a roadmap for integrating BCIs with multimodal sensors and artificial intelligence to create reliable, real-time, and ethically responsible systems for taste-driven sensory engineering. By consolidating these insights, this review aims to bridge the gap between neuroscience and engineering, advancing the objective understanding and technological exploration of how humans experience taste.

- NEUROPHYSIOLOGICAL FOUNDATIONS OF TASTE PERCEPTION

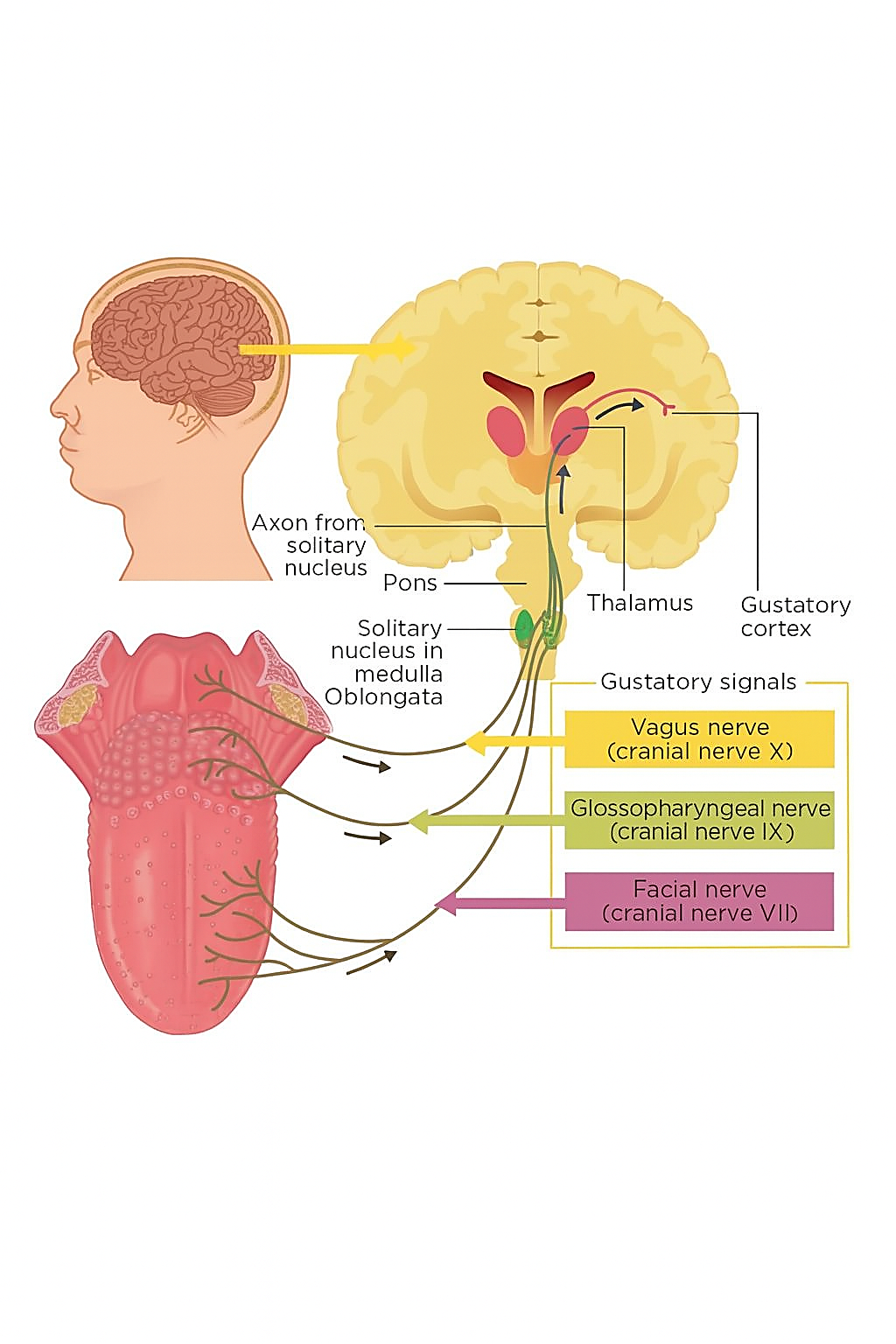

Human taste perception begins at the peripheral sensory level within the taste buds of the tongue, where specialized gustatory receptor cells detect chemical compounds present in food and beverages [16]. As shown in Figure 1, these receptor cells send neural signals through three main cranial nerves. The facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) transmits sensory input originating from the front portion of the tongue [17]. The glossopharyngeal nerve (cranial nerve IX) is responsible for carrying taste sensations arising from the back section of the tongue [18]. Meanwhile, the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) delivers sensory information derived from the regions of the pharynx and the epiglottis [19]. All these neural pathways converge in the solitary nucleus of the medulla oblongata, which acts as the first central relay for taste information [20]. From this point, gustatory signals travel through the pons and reach the thalamus, before projecting to higher brain centers such as the insular cortex and the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) [21]. These cortical areas, often referred to as the gustatory cortex, are responsible for conscious taste recognition, discrimination, and hedonic evaluation [22].

At the cortical level, the five fundamental categories of taste perception (namely sweetness, saltiness, sourness, bitterness, and umami) are represented by complex but overlapping neural activation patterns [23]. Sweet and umami tend to activate anterior regions of the insular and frontal opercular areas, which are linked with pleasant or rewarding sensations [24]. Bitter and sour flavors often engage posterior parts of the insular cortex that are associated with aversive or protective responses [25]. Salty taste produces intermediate activation because it plays both a sensory and homeostatic role [26]. This distributed neural representation supports the concept of population coding, in which networks of neurons work together to encode different dimensions of taste, including intensity, valence, and quality [27].

Findings from EEG and fNIRS studies have provided important insights into these gustatory processes. In EEG recordings, several event-related potential (ERP) components are observed during taste perception. The P200 component reflects early sensory detection [29]. The P300 component represents attention and stimulus evaluation [30]. The N400 component corresponds to cognitive and affective interpretation [31]. In the frequency domain, taste stimulation typically causes a reduction of alpha-band activity that indicates cortical activation, together with an increase in beta-band activity that reflects higher cognitive integration [32]. fNIRS studies complement these results by identifying hemodynamic changes in the insular and orbitofrontal regions during exposure to different taste qualities [33]. These findings form the physiological basis for non-invasive Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) applications that attempt to decode the brain’s electrical and metabolic responses to taste [34].

Taste processing also involves emotional and motivational circuits that modulate the sensory experience [35]. The amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex are central to this integration process. They link gustatory inputs with affective states and reward valuation [36]. Dopaminergic signaling in these regions strengthens learning and memory related to taste experiences, helping to shape food preferences and behavioral responses [37]. For this reason, taste perception cannot be described as a purely sensory event. It represents a unified neural experience that merges cognition, emotion, and motivation into one dynamic system [38]. Understanding the entire neurophysiological pathway illustrated in Figure 1 is essential for the advancement of BCI-based studies in taste perception. By capturing ERP signatures and brain oscillations related to insular and orbitofrontal activation, BCIs can serve as objective tools for analyzing taste-specific neural responses [39]. This foundation supports future developments in sensory engineering, flavor design, and affective computing, where taste is evaluated not only through behavior but also through measurable brain activity [40].

Figure 1. Overview of the gustatory neural circuits [28]

- BCI APPROACHES FOR DECODING TASTE

The application of BCI technology in the study of taste perception has opened new possibilities for understanding how neural signals represent gustatory information. Among the available BCI modalities, non-invasive techniques such as EEG and fNIRS are the most widely adopted [41]. These methods are preferred because they are safe, portable, and suitable for repeated testing in healthy participants. EEG provides high temporal resolution, which makes it ideal for capturing fast neural dynamics associated with taste discrimination [42]. In contrast, fNIRS offers better spatial resolution by measuring hemodynamic activity in cortical regions that process taste information, particularly in the insular and orbitofrontal cortices. The combination of these two modalities allows researchers to examine both electrical and metabolic responses, creating a more comprehensive picture of gustatory processing [43].

The general signal processing pipeline in taste-related BCIs is composed of four fundamental stages. The initial stage involves signal acquisition, which entails capturing brain responses while participants are presented with systematically controlled gustatory stimuli [44], including liquid samples that correspond to the five basic taste categories (sweetness, sourness, saltiness, bitterness, and umami). The second step is artifact removal, where non-neural signals caused by eye movement, facial muscles, or swallowing are filtered to improve data quality [45]. The third step is feature extraction, in which meaningful neural characteristics are identified from the recorded signals. These features may include time-domain components such as event-related potentials (P200, P300, and N400), or frequency-domain patterns like alpha and beta power changes [46]. The final step is classification, where machine learning or deep learning models are used to differentiate between various taste conditions or hedonic responses [47]. Classical algorithms such as SVM and Linear Discriminant Analysis remain widely used due to their simplicity and interpretability, while newer approaches like CNNs and LSTM networks offer improved accuracy by capturing spatial and temporal dependencies within the data [48]-[50].

Research on brain-computer interfaces for taste perception has expanded considerably in recent years, beginning with early EEG investigations that explored neural correlates of sweetness and beverage evaluation. Mouillot et al. [51] reported that natural sucrose produced stronger and faster gustatory-evoked potentials compared to synthetic sweetening agents like aspartame and stevia. In the same year, Chen et al. [52] integrated virtual-reality contexts into EEG experiments and found that visual–taste congruency enhanced the perceived sweetness of beverages although it did not necessarily increase product liking. Alvino et al. [53] extended EEG analysis to the evaluation of red wine, revealing beta-band oscillations associated with sensory and reward processing during wine appraisal. These foundational studies demonstrated that EEG could detect subtle variations in hedonic and cognitive responses to different taste conditions.

Subsequent research diversified the stimuli and analytical frameworks. HajiHosseini et al. [54] used sixty-four-channel EEG to examine foods differing in health value and taste and observed that alpha-band activity encoded value integration whereas theta-band activity reflected self-regulation during decision making. Huang et al. [55] employed intracranial stereotactic EEG in epilepsy patients and discovered that the posterior insula encoded anticipation of food whereas the anterior insula and frontal operculum responded selectively to palatable cues. In a related study, Sinding et al. [56] observed that introducing a beef scent intensified participants’ perception of the soup’s saltiness, and influenced late ERP components such as P3, confirming the role of olfactory–gustatory interaction. Franco et al. [57] combined EEG and blood-volume pulse measurements to study group identity and branding effects on taste judgments. Their findings showed that social labeling influenced purchase intention more strongly than physiological taste response, emphasizing contextual modulation in taste perception.

During 2022, researchers further explored multimodal and computational aspects of BCI. Hong et al. [58] demonstrated that inhalation of Agastache rugosa essential oil increased alertness and freshness through broad-band EEG activation, while Atzingen et al. [59] used a CNN with two-channel EEG to distinguish caloric from non-caloric sweeteners, achieving high classification accuracy despite minimal electrode input. Wu et al. [60] analyzed umami-related EEG patterns and found low-frequency delta and theta activity with right-hemisphere dominance, suggesting lateralized processing of monosodium glutamate. Arroyo et al. [61] used statistical features from dry-electrode EEG to discriminate between sweet and non-sweet stimuli across odor, taste, and flavor conditions, revealing parietal and temporal involvement. Çelik et al. [62] applied olfactory event-related potentials in a clinical population and showed that OERP analysis could identify anosmia and malingering, demonstrating potential diagnostic value. Collectively, these 2022 studies highlighted the adaptability of EEG and hybrid systems for both research and applied contexts.

The following year, methodological diversity continued to expand. Stuldreher et al. [63] reported that food neophobia heightened attentional ERP responses and reduced consumption volume when participants viewed unfamiliar foods. Hosang et al. [64] examined carbohydrate mouth rinsing and observed modulation of visuospatial attention through N1pc and N2pc components without behavioral change. Naser et al. [65] introduced a reduced-channel EEG approach using Hilbert Transform and Wavelet Packet Decomposition, which improved accuracy and efficiency. Jing et al. [66] investigated cross-modal effects of music on taste evaluation and found that classical music enhanced preference for sweet food while rock music increased cognitive control over salty food consumption. Ullah et al. [67] validated surface electromyography as a potential proxy for taste perception by successfully recognizing six electronic taste states that mirrored real taste experiences. Mastinu et al. [68] performed large-scale time–frequency EEG on dysgeusia patients and demonstrated that gustatory event-related potentials provided higher diagnostic sensitivity than traditional assessments. These developments marked a turning point where BCI research began to include clinical diagnostics and emotional modulation alongside sensory decoding.

From 2025 onward, the field saw a sharp increase in algorithmic innovation and dataset complexity. Xia et al. [69] developed a CNN-based channel-spatial attention model that improved recognition of four basic tastes while maintaining high accuracy. Li et al. [70] linked EEG band activity to food palatability, showing that more appetizing dishes elevated arousal and motivation levels. Stickel et al. [71] used frontal alpha asymmetry to show that explicit liking aligned with implicit neural responses only for taste-labeled drinks, indicating subconscious bias. Another work by Xia et al. [72] employed a Local-Global Fusion Transformer to quantify odor-enhanced sweetness, identifying frontal and parietal activation patterns. Albayrak et al. [73] combined EEG and EMG signals to test the effects of vagus nerve stimulation and found no direct EEG change but an increased eye-blink rate associated with reward anticipation. Zhao et al. [74] examined nine citrus essential oils and revealed that concentrated samples evoked stronger brain activity yet lower subjective acceptability, reflecting the neural basis of flavor intensity.

Further refinement in 2025 involved controlled stimulus delivery and multimodal measurement. Liu et al. [75] designed an automated taste-delivery system that improved timing precision and decoding accuracy for salty taste EEG. Stickel et al. [76] combined EEG and eye-tracking data to evaluate labeled yogurts and reported that “health” labels reduced perceived tastiness and liking. Wang et al. [77] demonstrated that EEG signals could differentiate sweetener types and concentrations even under equal sweetness conditions, indicating fine neural discrimination. De et al. [78] introduced TasteNet, an entropy-based deep network capable of classifying six basic tastes with higher accuracy than prior models. Wang et al. [79] used EEG microstate analysis to track brain dynamics during exposure to alcoholic beverages of varying alcohol content and found that higher concentrations shifted attentional and evaluative states. Another study by Wang et al. [80] combined EEG source localization and connectivity mapping to show that volatile compounds enhanced salty taste perception through olfactory-gustatory integration.

Additional contributions in 2025 explored relaxation, molecular modeling, and affective responses. Park et al. [81] applied s-LORETA analysis to EEG data collected during consumption of rice-bran cookies and found that these products promoted relaxation and reduced stress. Yang et al. [82] used graph convolutional networks to design safer dairy flavor substitutes and demonstrated cortical activation patterns comparable to standard diacetyl. Pereira et al. [83] confirmed that sweet and umami tastes elicited distinct neural and emotional patterns measurable through EEG and self-assessment manikins. Chen et al. [84] analyzed Baijiu beverages of varying mouthfeel and observed that intensity levels influenced comfort-related neural activity. Fu et al. [85] combined EEG with facial-expression tracking to show that sweet and salty food pairings improved liking and could be predicted by multimodal features. The latest development by Wang et al. [86] introduced TEDNet, a transformer-based local–global attention model that achieved state-of-the-art accuracy in decoding the four basic tastes from EEG signals.

Table 1. Summary of recent studies on BCI applications in human taste perception

Author(s) | Year | BCI Modality | Stimuli / Taste Type | Dataset / Participants | Feature Extraction / Analysis | Main Findings |

Mouillot et al. [51] | 2020 | EEG (9 electrodes) | Sweet taste using sucrose, aspartame, and stevia | 20 healthy adults aged 19–27 | Latency and amplitude of GEP peaks | Natural sugar induced stronger and faster activation than artificial sweeteners |

Chen et al. [52] | 2020 | EEG (9 channels, VR) | Sweet beverage in sweet, bitter, and neutral VR scenes | 41 adults aged 27 ± 2 | Alpha-band frontal asymmetry and self-report ratings | Visual–taste congruency enhanced sweetness perception without increasing liking |

Alvino et al. [53] | 2020 | EEG (32 electrodes) | Red wines differing in price and origin | 26 adults aged 18–40 | FFT and beta-band power with ANOVA | Beta oscillations linked to reward and sensory processing during wine evaluation |

HajiHosseini et al. [54] | 2021 | EEG (64 channels) | Food items varying in taste and health | 50 adults aged 17–31 | ERP and time–frequency analysis of alpha and theta | Alpha encoded value integration while theta reflected self-regulation |

Huang et al. [55] | 2021 | Intracranial SEEG | Palatable and neutral liquids | 11 epilepsy patients | Broadband (70–170 Hz) time–frequency analysis | Posterior insula encoded food anticipation and anterior insula responded to palatable cues |

Sinding et al. [56] | 2021 | EEG (5 electrodes) | Salty soup with or without beef aroma | 13 adults aged 18–30 | ERP (P1, P3) latency and amplitude | Odor enhanced perceived saltiness and affected late cognitive flavor processing |

Franco et al. [57] | 2021 | EEG and BVP | Watermelon drink with sponsor labels | 90 football fans | Alpha power and HRV analysis | Group identity influenced buying intention more than taste |

Hong et al. [58] | 2022 | EEG (29 electrodes) | Agastache rugosa essential oil | 38 adults (19 male, 19 female) | Power spectral analysis across theta–gamma bands | Essential oil increased alertness and freshness while reducing drowsiness |

Atzingen et al. [59] | 2022 | EEG (2 electrodes) | Passion fruit juice with various sweeteners | 11 adults aged 19–55 | Filtered EEG (8–40 Hz) for CNN input | CNN differentiated caloric vs. non-caloric sweeteners with high accuracy |

Wu et al. [60] | 2022 | EEG (8 electrode pairs) | Umami taste (MSG at 3 concentrations) | 10 adults aged 24 ± 1 | Power spectral density (1–100 Hz) | Umami evoked low-frequency δ and θ activity with right-side dominance |

Arroyo et al. [61] | 2022 | EEG (64 dry electrodes) | Sweet odor, sweet taste, non-sweet flavor | 18 adults aged 24–35 | Time-domain statistical descriptors | EEG distinguished sweet vs. non-sweet across modalities with parietal involvement |

Çelik et al. [62] | 2022 | EEG (OERP) | Odor stimuli (n-amyl acetate) | 98 post-trauma patients | ERP waveform (Fz–Cz–Pz) | OERP helped detect anosmia and malingering in forensic assessment |

Stuldreher et al. [63] | 2023 | EEG (32 electrodes) | Familiar and unfamiliar food images | 43 adults aged 19–64 | ERP (LPP) and inter-subject correlation | Food neophobia increased attention and reduced sip size for unfamiliar foods |

Hosang et al. [64] | 2023 | EEG (60 electrodes) | Carbohydrate and non-nutritive mouth rinse | 53 adults aged 26 ± 4 | ERP (N1pc, N2pc) amplitude | Carbohydrate rinse modulated visuospatial attention without behavioral change |

Naser et al. [65] | 2024 | EEG (17–256 channels) | Taste and odor stimuli | 10 for taste, 5 for odor, 29 for motor imagery | Hilbert Transform and Wavelet Packet | RSCS improved accuracy with fewer EEG channels |

Jing et al. [66] | 2024 | EEG (64 channels) | Sweet and salty foods under music styles | 24 college students | ERP (P2, N2, N3, LPC) | Classical music enhanced sweet preference while rock increased control for salty food |

Ullah et al. [67] | 2024 | Surface EMG | Electronic taste stimuli | 17 adults (8 used for data) | Time and frequency features | sEMG recognized six electronic taste states correlating with real tastes |

Mastinu et al. [68] | 2024 | EEG (128 electrodes) | Salty taste (NaCl concentrations) | 103 participants (44 dysgeusia, 59 controls) | Time–frequency and canonical averaging | Time–frequency analysis improved dysgeusia diagnosis |

Xia et al. [69] | 2025 | EEG (21 channels) | Sour, Sweet, Bitter, Salty | 20 participants, 1600 samples | CNN-CSA with Grad-CAM | CAM-Attention improved recognition efficiency with high accuracy |

Li et al. [70] | 2025 | EEG | Fried rice with varied palatability | 46 students aged 19–28 | Band analysis of theta–gamma | Delicious food increased arousal and motivation |

Stickel et al. [71] | 2025 | EEG (frontal alpha asymmetry) | Protein chocolate milk with labels | 118 adults aged 18–50 | PSD of alpha band | Taste label increased liking compared to health label |

Xia et al. [72] | 2025 | EEG | Sucrose mixed with odor compound | 16 adults aged 20–30 | Local–Global Fusion Transformer | Odor enhanced sweetness with frontal and parietal activation |

Albayrak et al. [73] | 2025 | EEG and EMG | Chocolate milk | 15 healthy adults | ICA and artifact removal | tVNS did not alter EEG but sipping increased eye-blink rate linked to reward |

Zhao et al. [74] | 2025 | EEG | Nine citrus essential oils | 20 healthy adults | PSD and frequency analysis | Concentrated oils evoked stronger brain responses and lower acceptability |

Liu et al. [75] | 2025 | EEG | NaCl solutions (150 and 200 mmol/L) | 20 adults aged 24 ± 1 | DWT, GFP, PCA | Automated taste delivery improved precision of EEG decoding |

Stickel et al. [76] | 2025 | EEG and Eye Tracking | Dairy and plant yogurts | 154 participants aged 19–65 | PSD of alpha band and gaze metrics | Health labels reduced tastiness and liking |

Wang et al. [77] | 2025 | EEG | Sucrose and iso-sweet sweeteners | 28 adults aged 18–30 | PSD and AUC of bands | Brain differentiated sweetener type and concentration |

De et al. [78] | 2025 | EEG (19 electrodes) | Sweet, Sour, Salty, Bitter, Umami, Neutral | 51 adults aged 19–35 | CEEMDAN and entropy features | TasteNet classified six basic tastes with superior performance |

Wang et al. [79] | 2025 | EEG (64 channels) | Alcoholic stimuli (various ABV) | 20 adults | EEG microstate analysis | Alcohol concentration modulated sensory focus and re-evaluation |

Wang et al. [80] | 2025 | EEG (64 channels) | Salty taste enhanced by volatiles | 20 adults aged 19–26 | Time–frequency, source localization | Volatiles strengthened olfactory–gustatory integration |

Park et al. [81] | 2025 | EEG (21 channels, s-LORETA) | Rice bran cookies with sugar substitutes | 6 adults | Band analysis and source mapping | Cookies promoted relaxation and reduced stress |

Yang et al. [82] | 2025 | EEG (CSD and GCN) | Dairy flavor and diacetyl substitute | 177 evaluators | GCN molecular embedding and GA inverse design | Safe dairy flavor substitute matched cortical activation of original DA |

Pereira et al. [83] | 2025 | EEG (32 channels) | Five basic tastes | 28 adults aged 18–25 | PSD analysis of δ–γ bands | Sweet and umami produced distinct neural and emotional patterns |

Chen et al. [84] | 2025 | EEG (64 channels) | Baijiu with varied mouthfeel | 10 adults | PSD and time–frequency | Mouthfeel intensity affected neural comfort and perception |

Fu et al. [85] | 2025 | EEG and facial tracking | Baijiu flavors and food pairing | 53 total participants | EEG rhythm and FaceReader metrics | Sweet and salty pairings improved liking and predicted preference |

Wang et al. [86] | 2025 | EEG (21 electrodes) | Sweet, Sour, Salty, Bitter | 30 adults, 2400 samples | TEDNet with Local–Global Attention | Model achieved state-of-the-art decoding accuracy |

- BRAIN-COMPUTER INTERFACE APPLICATIONS IN TASTE PERCEPTION

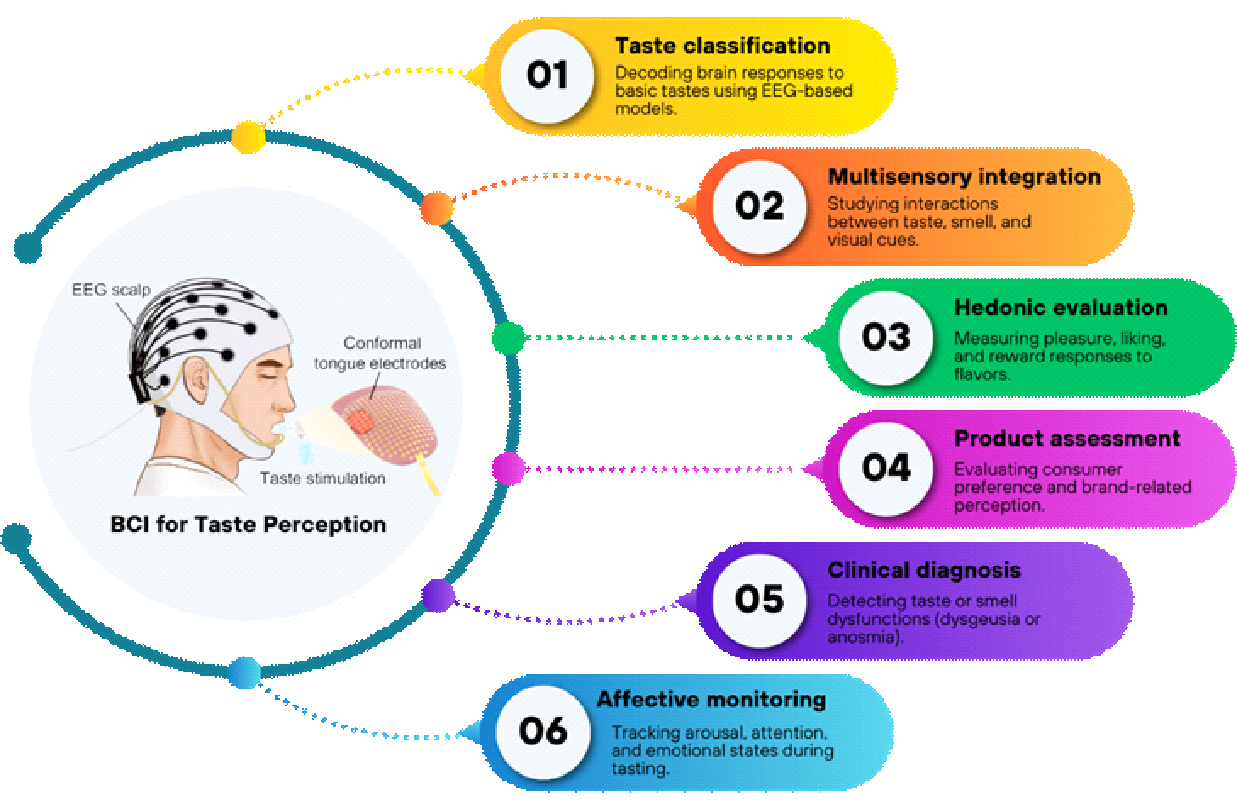

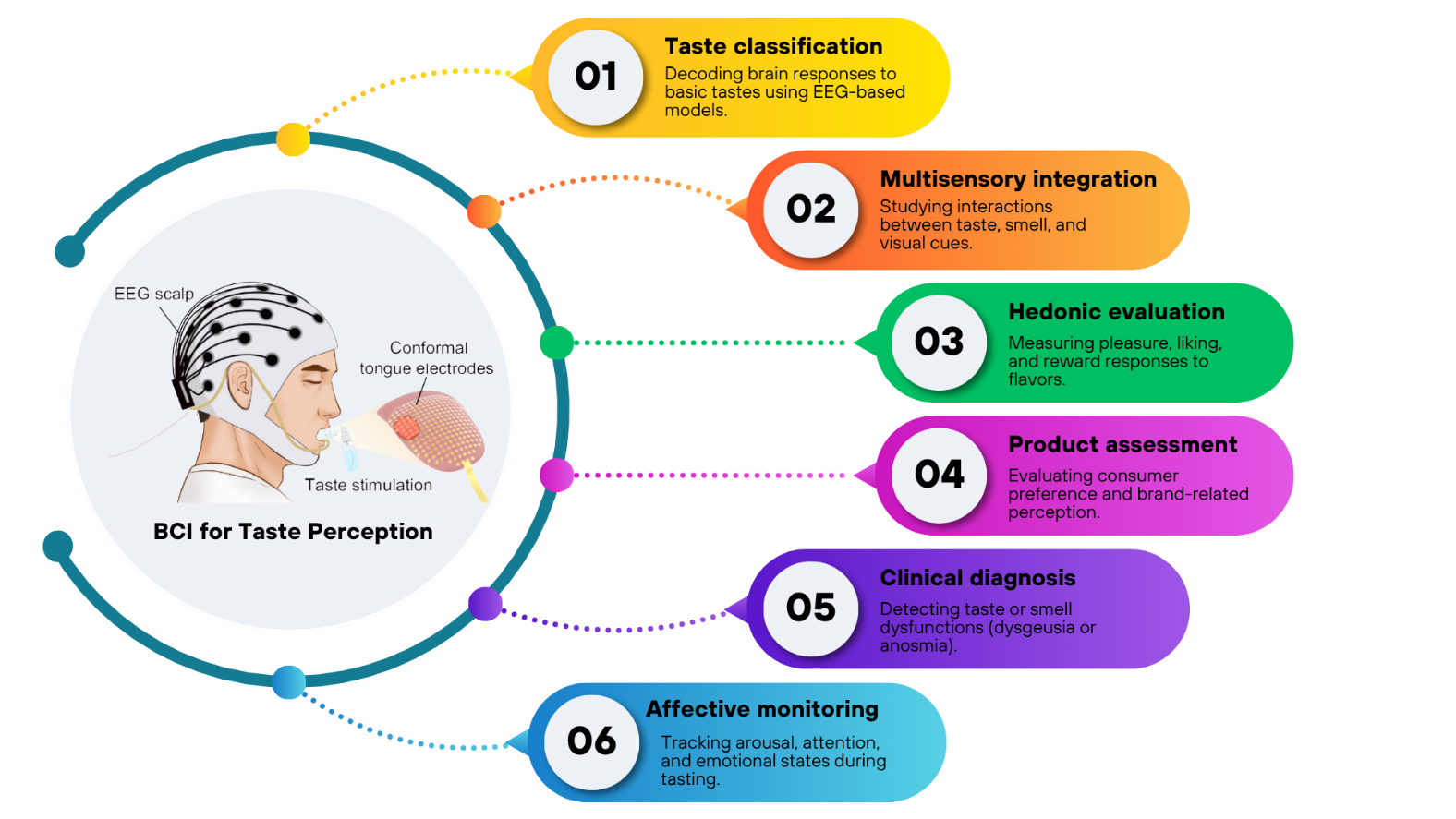

Recent developments in BCI research have demonstrated that decoding neural signals can provide valuable insights into how the human brain perceives and evaluates taste. Across multiple studies, EEG-based BCIs have been applied to classify different taste modalities, integrate sensory cues, measure hedonic experiences, evaluate consumer products, support clinical diagnosis, and monitor affective states. These diverse applications highlight the growing potential of BCI technology to serve as both a research and engineering tool in sensory neuroscience and food science can be seen in Figure 2.

Taste classification represents the most direct and widely explored application of BCIs in gustatory research. Several studies have successfully decoded neural signatures corresponding to the five basic tastes (sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami) using EEG and advanced learning algorithms. Early work by Mouillot et al. [51] and Wu et al. [60] identified distinct temporal and frequency-domain EEG patterns for sweet and umami stimuli, confirming the feasibility of objective taste discrimination. Later, De et al. [78] introduced TasteNet, which used entropy-based features to classify six basic tastes with high precision, while Xia et al. [69] and Wang et al. [86] demonstrated that deep models such as CNNs and Transformer-based networks could achieve state-of-the-art decoding accuracy. These findings indicate that EEG-based BCIs can reliably recognize taste-related brain activity, providing the foundation for automated flavor recognition systems.

Multisensory integration has also become a central theme in BCI-based taste studies. The perception of flavor arises not only from gustatory inputs but also from the interaction of taste, smell, and vision. Studies by Sinding et al. [56] and Wang et al. [80] revealed that the addition of aroma compounds or volatile cues enhanced taste perception by engaging both gustatory and olfactory cortical regions. Chen et al. [52] confirmed that visual context presented through virtual reality could modify the perceived sweetness of beverages, illustrating how cross-modal congruency shapes neural taste processing. Arroyo et al. [61] further demonstrated that EEG patterns could differentiate between sweet and non-sweet stimuli across taste and odor modalities, highlighting the brain’s ability to integrate sensory information dynamically.

Figure 2. BCI applications in Taste Perception

In terms of hedonic evaluation, BCIs have proven effective for measuring subjective pleasure and reward responses linked to flavor consumption. Alvino et al. [53] and HajiHosseini et al. [54] showed that beta- and theta-band oscillations corresponded to reward processing and self-regulation during food evaluation tasks. Li et al. [70] and Pereira et al. [83] observed that more palatable or umami-rich foods produced stronger emotional engagement and cortical activation associated with liking and motivation. Zhao et al. [74] added that intense citrus aromas evoked powerful neural responses correlated with lower subjective acceptability, reflecting the brain’s nuanced encoding of sensory pleasure and discomfort. These results underline the potential of EEG to objectively assess hedonic experience and preference formation.

BCI technology has also been utilized for product assessment, offering valuable tools for neuromarketing and sensory product design. Franco et al. [57] demonstrated that group identity and product labeling could modulate consumer purchase intention more than the taste itself, as reflected in EEG and physiological measures. Stickel et al. [71],[76] explored the influence of “health” versus “taste” labels and found that implicit neural responses, captured through frontal alpha asymmetry, often diverged from explicit self-reports of liking. Fu et al. [85] combined EEG with facial expression analysis and found that sweet and salty food pairings increased positive emotional responses and accurately predicted consumer preference. Together, these studies show that BCIs can reveal subconscious evaluations that traditional questionnaires may overlook, enabling data-driven approaches to product testing.

In clinical and diagnostic contexts, BCIs have shown promise in detecting gustatory and olfactory dysfunctions. Çelik et al. [62] used olfactory event-related potentials to identify anosmia and malingering among patients with post-traumatic smell loss, providing an objective electrophysiological tool for forensic evaluation. Mastinu et al. [68] applied EEG-based time–frequency analysis to patients with dysgeusia and found altered gustatory activity compared with healthy controls, which improved diagnostic sensitivity beyond standard gustatory event-related potentials. These findings suggest that BCIs can complement medical diagnostics by quantifying neural responses in patients with sensory impairments.

Finally, affective and cognitive state monitoring represents another emerging application of BCI in taste research. EEG markers of arousal, attention, and relaxation have been successfully measured during food consumption. Hong et al. [58] reported that exposure to aromatic essential oils increased alertness and reduced drowsiness, while Park et al. [81] showed that rice-bran cookies induced relaxation and lowered stress-related brain activity. Hosang et al. [64] found that carbohydrate mouth rinsing influenced visuospatial attention networks without altering behavior, and Wang et al. [79] demonstrated that varying alcohol concentrations modulated attentional and evaluative brain states. Such findings highlight the value of BCIs for tracking real-time emotional and attentional changes, paving the way for adaptive sensory environments and personalized food experiences.

- CHALLENGES AND EMERGING DIRECTIONS

Despite significant progress in applying brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) to the study of taste perception, several technical and methodological challenges remain unresolved. Most existing studies still rely on relatively small and homogeneous participant groups, often fewer than thirty individuals, which limits the statistical generalizability of their findings. Differences in electrode placement, recording duration, and taste delivery methods across studies introduce additional variability that complicates cross-study comparisons. Environmental control also plays a critical role, as taste responses can be influenced by external cues such as room odor, visual context, and even participant hunger state. These inconsistencies highlight the urgent need for standardized experimental protocols, shared datasets, and unified benchmarks to ensure reproducibility and comparability across laboratories.

Signal quality and interpretability present another key limitation. EEG and fNIRS signals used in taste-related BCIs are prone to low signal-to-noise ratios caused by motion artifacts, swallowing, and facial muscle activity during tasting. Although preprocessing techniques such as independent component analysis and adaptive filtering have improved data clarity, they cannot fully eliminate non-neural contamination. Moreover, the transient and overlapping nature of gustatory-evoked potentials makes it difficult to isolate specific neural components associated with individual taste qualities. The majority of studies, including those by Mouillot et al. [51] and Wu et al. [60], focused on single or binary taste classifications, whereas more complex and mixed flavor experiences remain largely unexplored. Future BCIs should therefore incorporate more robust artifact rejection algorithms and multimodal acquisition systems that can synchronize EEG, fNIRS, EMG, and behavioral measures for higher fidelity in taste decoding.

Another major challenge concerns data scarcity and model generalization. Although deep learning models such as CNN, Transformer, and entropy-based networks have achieved impressive accuracy in single-study settings [69],[78],[86], their generalizability across individuals and experimental setups remains limited. Many datasets are proprietary or collected under highly specific conditions, preventing meaningful cross-validation and meta-analysis. Building large, open-access, and well-annotated databases of taste-related EEG and fNIRS recordings is therefore an essential step toward developing transferable and explainable models. Transfer learning and domain adaptation techniques may help overcome subject variability, allowing BCIs to function reliably across different user populations.

Beyond technical barriers, future research must also address the interpretability and ethical implications of taste decoding. Current deep neural models, while accurate, often behave as black boxes, providing little insight into the underlying neurophysiological mechanisms. Approaches using explainable artificial intelligence such as Grad-CAM and SHAP could visualize the cortical regions and frequency bands that drive classification decisions, enabling a deeper comprehension of the neural processes through which the brain represents and interprets gustatory perception. At the same time, the collection and analysis of neural data raise critical ethical concerns related to data privacy, participant consent, and the risk of information misuse. Taste preferences are closely tied to individual identity, emotion, and cultural background, and therefore require careful data governance and transparent use policies in both research and industry applications.

Several emerging directions are already shaping the next generation of BCI-based sensory systems. The integration of multimodal technologies, including EEG–fNIRS hybrids, electromyography, and eye-tracking, offers the potential to capture richer representations of taste-related brain activity. Studies such as Atzingen et al. [59] and Fu et al. [85] demonstrated that combining neural and peripheral physiological signals enhances model performance and emotional interpretation. Advances in portable and wireless EEG devices will further support real-world experiments beyond laboratory environments, enabling mobile monitoring of flavor perception in natural eating contexts. Additionally, immersive media technologies encompassing VR and AR, previously explored by Chen et al. [52], can be merged with BCI systems to simulate and manipulate multisensory dining experiences, contributing to both research and interactive food design.

Looking forward, the convergence of neuroscience, machine learning, and sensory engineering is expected to transform BCIs from experimental tools into practical systems for health and industry. Clinical applications such as the detection of dysgeusia and anosmia [62],[68] may evolve into real-time diagnostic platforms capable of monitoring taste recovery in neurological patients. In parallel, affective BCIs could guide the development of personalized nutrition and adaptive flavor modulation that responds to users’ emotional and physiological states. The field is thus moving toward a future where taste is no longer evaluated solely through subjective experience but decoded objectively through brain signals, paving the way for a new generation of intelligent, human-centered sensory technologies.

- CONCLUSIONS

Research on brain-computer interfaces for taste perception has evolved rapidly, transforming the study of gustatory processing from subjective observation to objective neural decoding. EEG and fNIRS technologies have proven effective in capturing brain responses to basic tastes, emotional valence, and cognitive evaluation, enabling quantifiable insights into how the brain encodes flavor experiences. Advances in signal processing and machine learning have made it possible to classify multiple taste modalities with increasing precision, marking a shift from exploratory neuroscience toward applied neuroengineering. Beyond taste classification, BCIs have provided new perspectives on multisensory integration, emotional processing, and consumer perception. Findings show that taste perception is influenced by visual and olfactory cues, as well as by cognitive and affective contexts such as reward, motivation, and product labeling. These insights have positioned BCIs as valuable tools for sensory analysis, neuromarketing, and affective computing, while also demonstrating potential in clinical applications for diagnosing taste and smell disorders.

Despite this progress, several challenges remain. Many studies are limited by small datasets, non-standardized experimental designs, and variability in signal quality caused by motion artifacts or individual differences. Deep learning architectures deliver high precision but often lack clarity in their decision-making, emphasizing the need for more transparent and interpretable methods. Future research should focus on building open-access databases, refining multimodal acquisition systems, and developing portable BCIs for real-world sensory environments. In summary, BCIs offer a promising and interdisciplinary framework for decoding human taste perception. By merging neuroscience, engineering, and artificial intelligence, they pave the way for objective and personalized evaluation of flavor experiences. Continued innovation in this field will enable the creation of neuroadaptive sensory systems capable of understanding and enhancing the complex relationship between the human brain and the sense of taste.

DECLARATION

Author Contribution

All authors contributed equally to the main contributor to this paper. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the Department of Medical Technology, Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember, for the facilities and support in this research. The authors also gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember for this work, under project scheme of the Publication Writing and IPR Incentive Program (PPHKI) 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- B. Chen, X. Lin, Z. Liang, X. Chang, Z. Wang, M. Huang, and X.-A. Zeng, “Advances in food flavor analysis and sensory evaluation techniques and applications: Traditional vs emerging,” Food Chemistry, vol. 494, p. 146235, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2025.146235.

- J. Wang et al., “From Traditional to Intelligent, A Review of Application and Progress of Sensory Analysis in Alcoholic Beverage Industry,” Food Chemistry X, vol. 23, pp. 101542–101542, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2024.101542.

- Y. Shu, H. Gao, Y. Wang, and Y. Wei, “Food Emotional Perception and Eating Willingness Under Different Lighting Colors: A Preliminary Study Based on Consumer Facial Expression Analysis,” Foods, vol. 14, no. 19, p. 3440, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14193440.

- G. Wang, X. Wang, H. Cheng, H. Li, Z. Qin, F. Zheng, X. Ye, and B. Sun, “Application of electroencephalogram (EEG) in the study of the influence of different contents of alcohol and Baijiu on brain perception,” Food Chemistry, vol. 462, pp. 140969–140969, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.140969.

- L. Pallante et al., “On the human taste perception: Molecular-level understanding empowered by computational methods,” Trends in Food Science & Technology, vol. 116, pp. 445–459, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2021.07.013.

- J. Peksa and D. Mamchur, “State-of-the-Art on Brain-Computer Interface Technology,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 13, p. 6001, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/s23136001.

- S. G. H. Meyerding, X. He, and A. Bauer, “Neuronal correlates of basic taste perception and hedonic evaluation using functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS),” Applied Food Research, vol. 4, no. 2, p. 100477, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afres.2024.100477.

- A. Byrne, E. Bonfiglio, C. Rigby, and N. Edelstyn, “A systematic review of the prediction of consumer preference using EEG measures and machine-learning in neuromarketing research,” Brain Informatics, vol. 9, no. 1, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40708-022-00175-3.

- X. Xia, Y. Yang, Y. Shi, W. Zheng, and H. Men, “Decoding human taste perception by reconstructing and mining temporal-spatial features of taste-related EEGs,” Applied Intelligence, vol. 54, no. 5, pp. 3902–3917, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10489-024-05374-5.

- J. Mai, S. Li, Z. Wei, and Y. Sun, “Implicit Measurement of Sweetness Intensity and Affective Value Based on fNIRS,” Chemosensors, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 36–36, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors13020036.

- H. Ahuja, S. Badhwar, H. Edgell, M. Litoiu, and L. E. Sergio, “Machine learning algorithms for detection of visuomotor neural control differences in individuals with PASC and ME,” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, vol. 18, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2024.1359162.

- Y. Gao, N. Lewis, V. D. Calhoun, and R. L. Miller, “Interpretable LSTM model reveals transiently-realized patterns of dynamic brain connectivity that predict patient deterioration or recovery from very mild cognitive impairment,” vol. 161, pp. 107005–107005, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.107005.

- A. D. Wibawa, N. Fatih, Y. Pamungkas, M. Pratiwi, P. A. Ramadhani and Suwadi, "Time and Frequency Domain Feature Selection Using Mutual Information for EEG-based Emotion Recognition," 2022 9th International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Computer Science and Informatics (EECSI), pp. 19-24, 2022, https://doi.org/10.23919/EECSI56542.2022.9946522.

- H. Zhang, L. Jiao, S. Yang, H. Li, X. Jiang, J. Feng, S. Zou, Q. Xu, J. Gu, X. Wang, and B. Wei, “Brain-computer interfaces: The innovative key to unlocking neurological conditions,” International Journal of Surgery, vol. 110, no. 9, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1097/js9.0000000000002022.

- X.-Y. Liu et al., “Recent applications of EEG-based brain-computer-interface in the medical field,” Military Medical Research, vol. 12, no. 1, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-025-00598-z.

- C. Spence, “The tongue map and the spatial modulation of taste perception,” Current Research in Food Science, vol. 5, pp. 598–610, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crfs.2022.02.004.

- M. L.-Jiménez et al., “On the Cranial Nerves,” NeuroSci, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 8–38, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci5010002.

- V. Tereshenko et al., “Axonal mapping of the motor cranial nerves,” Frontiers in Neuroanatomy, vol. 17, Jun. 2023, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnana.2023.1198042.

- M. M. Ottaviani and V. G. Macefield, “Structure and Functions of the Vagus Nerve in Mammals,” Comprehensive physiology, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 3989–4037, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2040-4603.2022.tb00237.x.

- J. Forstenpointner, A. M. S. Maallo, I. Elman, S. Holmes, R. Freeman, R. Baron, and D. Borsook, “The solitary nucleus connectivity to key autonomic regions in humans,” European Journal of Neuroscience, vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 3938–3966, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.15691.

- E. R. Delay and S. D. Roper, “Umami Taste Signaling from the Taste Bud to Cortex,” Food and Health, pp. 43–71, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-32692-9_3.

- K. Jezierska, A. C.-Płoska, J. Zaleska, and W. Podraza, “Gustatory-Visual Interaction in Human Brain Cortex: fNIRS Study,” Brain Sciences, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 92–92, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15010092.

- J. A. Avery, A. G. Liu, J. E. Ingeholm, C. D. Riddell, S. J. Gotts, and A. Martin, “Taste Quality Representation in the Human Brain,” The Journal of Neuroscience, vol. 40, no. 5, pp. 1042–1052, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.1751-19.2019.

- P. Han, M. Mohebbi, H.-S. Seo, and T. Hummel, “Sensitivity to sweetness correlates to elevated reward brain responses to sweet and high-fat food odors in young healthy volunteers,” NeuroImage, vol. 208, p. 116413, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116413.

- J. D. Boughter and M. Fletcher, “Rethinking the role of taste processing in insular cortex and forebrain circuits,” Current Opinion in Physiology, vol. 20, pp. 52–56, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cophys.2020.12.009.

- A. Rosa, F. Loy, I. Pinna, and C. Masala, “Role of Aromatic Herbs and Spices in Salty Perception of Patients with Hyposmia,” Nutrients, vol. 14, no. 23, pp. 4976–4976, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14234976.

- S. D. Roper, “Encoding Taste: From Receptors to Perception,” Handbook of experimental pharmacology, vol. 275, pp. 53–90, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/164_2021_559.

- M. Andrade, “The senses 3: exploring the interrelated senses of smell and taste,” Nursing Times, vol. 21, 2022, https://www.nursingtimes.net/neurology/the-senses-3-exploring-the-interrelated-senses-of-smell-and-taste-21-11-2022/.

- C.-L. Shen et al., “P50, N100, and P200 Auditory Sensory Gating Deficits in Schizophrenia Patients,” Frontiers in Psychiatry, vol. 11, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00868.

- G. R.-Bermúdez, B. Naret, and A. R. Teixeira, “Analysis of P300 Evoked Potentials to Determine Pilot Cognitive States,” Sensors, vol. 25, no. 19, p. 6201, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/s25196201.

- C. Guida, M. J. B. Kim, O. A. Stibolt, A. Lompado, and J. E. Hoffman, “The N400 component reflecting semantic and repetition priming of visual scenes is suppressed during the attentional blink,” Attention, perception & psychophysics, vol. 87, no. 4, pp. 1199–1218, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-024-02997-1.

- J. Gallina, G. Marsicano, V. Romei, and C. Bertini, “Electrophysiological and Behavioral Effects of Alpha-Band Sensory Entrainment: Neural Mechanisms and Clinical Applications,” Biomedicines, vol. 11, no. 5, p. 1399, May 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11051399.

- J. Chmiel and A. Malinowska, “The Neural Correlates of Chewing Gum—A Neuroimaging Review of Its Effects on Brain Activity,” Brain Sciences, vol. 15, no. 6, p. 657, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15060657.

- M. Maram, M. A. Khalil and K. George, "Analysis of Consumer Coffee Brand Preferences Using Brain-Computer Interface and Deep Learning," 2023 IEEE 7th International Conference on Information Technology, Information Systems and Electrical Engineering (ICITISEE), pp. 227-232, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICITISEE58992.2023.10404368.

- S. Y. Ki and Y. T. Jeong, “Neural circuits for taste sensation,” Molecules and Cells, vol. 47, no. 7, pp. 100078–100078, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mocell.2024.100078.

- E. T. Rolls, “Emotion, motivation, decision-making, the Orbitofrontal cortex, Anterior Cingulate cortex, and the Amygdala,” Brain Structure and Function, vol. 228, no. 5, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-023-02644-9.

- C. A. Zimmerman et al., “A neural mechanism for learning from delayed postingestive feedback,” Nature, pp. 1–10, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08828-z.

- M. E. Doyle, H. U. Premathilake, Q. Yao, C. H. Mazucanti, and J. M. Egan, “Physiology of the tongue with emphasis on taste transduction,” Physiological Reviews, vol. 103, no. 2, pp. 1193–1246, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00012.2022.

- A. K.-Sterniuk, N. Browarska, A. Al-Bakri, M. Pelc, J. Zygarlicki, M. Sidikova, R. Martinek, and E. J. Gorzelanczyk, “Summary of over Fifty Years with Brain-Computer Interfaces—A Review,” Brain Sciences, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 43, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11010043.

- Y. Guo, X. Xia, Y. Shi, Y. Ying, and H. Men, “Olfactory EEG induced by odor: Used for food identification and pleasure analysis,” Food Chemistry, vol. 455, pp. 139816–139816, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.139816.

- A. Tonin, M. Semprini, P. Kiper, and D. Mantini, “Brain-Computer Interfaces for Stroke Motor Rehabilitation,” Bioengineering, vol. 12, no. 8, pp. 820–820, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12080820.

- T. Yang et al., “Exploring the neural correlates of fat taste perception and discrimination: Insights from electroencephalogram analysis,” Food Chemistry, vol. 450, p. 139353, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.139353.

- E. Boot et al., “fNIRS a novel neuroimaging tool to investigate olfaction, olfactory imagery, and crossmodal interactions: a systematic review,” Frontiers in Neuroscience, vol. 18, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2024.1266664.

- A. M. Dietsch, R. M. Westemeyer, and D. H. Schultz, “Brain activity associated with taste stimulation: A mechanism for neuroplastic change?,” Brain and Behavior, vol. 13, no. 4, p. e2928, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.2928.

- A. Farizal, A. D. Wibawa, D. P. Wulandari and Y. Pamungkas, "Investigation of Human Brain Waves (EEG) to Recognize Familiar and Unfamiliar Objects Based on Power Spectral Density Features," 2023 International Seminar on Intelligent Technology and Its Applications (ISITIA), pp. 77-82, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/ISITIA59021.2023.10221052.

- N. Huidobro, R. M.-Andrade, I. M.-Balbuena, C. Trenado, M. T. Bello, and E. T. Rodríguez, “Electroencephalographic Biomarkers for Neuropsychiatric Diseases: The State of the Art,” Bioengineering, vol. 12, no. 3, p. 295, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12030295.

- R. Aziza, E. Alessandrini, C. Matthews, S. R. Ranmal, Z. Zhou, E. H. Davies, and C. Tuleu, “Using facial reaction analysis and machine learning to objectively assess the taste of medicines in children,” PLOS Digital Health, vol. 3, no. 11, pp. e0000340–e0000340, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pdig.0000340.

- S. R. M.-Castelblanco, M. A. V.-Guerrero, and M. C.-Cuervo, “Artificial Intelligence Approaches for EEG Signal Acquisition and Processing in Lower-Limb Motor Imagery: A Systematic Review,” Sensors, vol. 25, no. 16, pp. 5030–5030, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/s25165030.

- Y. Pamungkas and U. W. Astuti, "Comparison of Human Emotion Classification on Single-Channel and Multi-Channel EEG using Gate Recurrent Unit Algorithm," 2023 International Conference on Computer Science, Information Technology and Engineering (ICCoSITE), pp. 1-6, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCoSITE57641.2023.10127686.

- A. Jovic, N. Frid, K. Brkic, and M. Cifrek, “Interpretability and accuracy of machine learning algorithms for biomedical time series analysis – a scoping review,” Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, vol. 110, p. 108153, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2025.108153.

- T. Mouillot et al., “Differential Cerebral Gustatory Responses to Sucrose, Aspartame, and Stevia Using Gustatory Evoked Potentials in Humans,” Nutrients, vol. 12, no. 2, p. 322, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020322.

- Y. Chen, A. X. Huang, I. Faber, G. Makransky, and F. J. A. P.-Cueto, “Assessing the Influence of Visual-Taste Congruency on Perceived Sweetness and Product Liking in Immersive VR,” Foods, vol. 9, no. 4, p. 465, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9040465.

- L. Alvino, R. van der Lubbe, R. A. M. Joosten, and E. Constantinides, “Which wine do you prefer? An analysis on consumer behaviour and brain activity during a wine tasting experience,” Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, vol. 32, no. 5, pp. 1149–1170, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1108/apjml-04-2019-0240.

- A. HajiHosseini and C. A. Hutcherson, “Alpha oscillations and event-related potentials reflect distinct dynamics of attribute construction and evidence accumulation in dietary decision making,” eLife, vol. 10, 2021, https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.60874.

- Y. Huang, B. W. Kakusa, A. Feng, S. Gattas, R. S. Shivacharan, E. B. Lee, J. J. Parker, F. M. Kuijper, D. A. N. Barbosa, C. J. Keller, C. Bohon, A. Mikhail, and C. H. Halpern, “The insulo-opercular cortex encodes food-specific content under controlled and naturalistic conditions,” Nature Communications, vol. 12, no. 1, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23885-4.

- C. Sinding, H. Thibault, T. Hummel, and T. T.-Danguin, “Odor-Induced Saltiness Enhancement: Insights Into The Brain Chronometry Of Flavor Perception,” Neuroscience, vol. 452, pp. 126–137, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.10.029.

- S. Franco, A. M. Abreu, R. Biscaia, and S. Gama, “Sports ingroup love does not make me like the sponsor’s beverage but gets me buying it,” PLOS ONE, vol. 16, no. 7, p. e0254940, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0254940.

- M. Hong, H. Jang, S. Bo, M. Kim, P. Deepa, J. Park, K. Sowndhararajan, and S. Kim, “Changes in Human Electroencephalographic Activity in Response to Agastache rugosa Essential Oil Exposure,” Behavioral sciences, vol. 12, no. 7, pp. 238–238, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12070238.

- G. Voltani, H. Arteaga, A. Rodrigues, N. F. Ortega, J. Xavier, and A. Carolina, “The convolutional neural network as a tool to classify electroencephalography data resulting from the consumption of juice sweetened with caloric or non-caloric sweeteners,” Frontiers in Nutrition, vol. 9, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.901333.

- B. Wu, X. Zhou, I. Blank, and Y. Liu, “Investigating the influence of monosodium L-glutamate on brain responses via scalp-electroencephalogram (scalp-EEG),” Food Science and Human Wellness, vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 1233–1239, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fshw.2022.04.019.

- E. R.-Arroyo, J. Soria, M. Mora, F. Laport, A. M.-F.-de-Leceta, and L. V.-Araújo, “Exploratory Research on Sweetness Perception: Decision Trees to Study Electroencephalographic Data and Its Relationship with the Explicit Response to Sweet Odor, Taste, and Flavor,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 18, pp. 6787–6787, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/s22186787.

- C. Çelik, H. Güler, and M. Pehlivan, “Medicolegal aspect of loss of smell and olfactory event-related potentials,” Egyptian Journal of Forensic Sciences, vol. 12, no. 1, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1186/s41935-022-00306-1.

- I. V. Stuldreher, D. Kaneko, H. Hiraguchi, J. B. F. van Erp, and A.-M. Brouwer, “EEG measures of attention toward food-related stimuli vary with food neophobia,” Food Quality and Preference, vol. 106, p. 104805, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2022.104805.

- T. Hosang, S. Laborde, A. Löw, M. Sprengel, N. Baum, and T. Jacobsen, “How Attention Changes in Response to Carbohydrate Mouth Rinsing,” Nutrients, vol. 15, no. 13, pp. 3053–3053, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15133053.

- A. Naser and Ö. Aydemir, “Enhancing EEG Signal Classification With a Novel Random Subset Channel Selection Approach: Applications in Taste, Odor, and Motor Imagery Analysis,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 145608–145618, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2024.3473810.

- Y. Jing, Z. Xu, Y. Pang, X. Liu, J. Zhao, and Y. Liu, “The Neural Correlates of Food Preference among Music Kinds,” Foods, vol. 13, no. 7, pp. 1127–1127, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13071127.

- A. Ullah, F. Zhang, Z. Song, Y. Wang, S. Zhao, W. Riaz, and G. Li, “Surface Electromyography-Based Recognition of Electronic Taste Sensations,” Biosensors, vol. 14, no. 8, pp. 396–396, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/bios14080396.

- M. Mastinu, L. S. Grzeschuchna, C. Mignot, C. Guducu, V. Bogdanov, and T. Hummel, “Time–frequency analysis of gustatory event related potentials (gERP) in taste disorders,” Scientific Reports, vol. 14, no. 1, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52986-5.

- X. Xia, Q. Wang, H. Wang, C. Liu, P. Li, Y. Shi, and H. Men, “Optimizing Food Taste Sensory Evaluation Through Neural Network-Based Taste Electroencephalogram Channel Selection,” IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, vol. 74, pp. 1–9, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1109/tim.2025.3551994.

- H. Li, S. Li, K. Matsuo, and T. Okamoto, “Brain activity during a cognitive task after consuming food of varying palatability,” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 16, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1522812.

- L. Stickel, K. G. Grunert, and L. Lähteenmäki, “Implicit and explicit liking of a snack with health- versus taste-related information,” Food Quality and Preference, vol. 122, p. 105293, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2024.105293.

- X. Xia, Y. Cheng, Z. Zhang, Z. Hua, Q. Wang, Y. Shi, and H. Men, “Advancing research on odor-induced sweetness enhancement: A EEG local-global fusion transformer network for sweetness quantification combined with EEG technology,” Food Chemistry, vol. 463, p. 141533, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.141533.

- S. Albayrak, B. Aydin, G. Özen, F. Yalçin, M. Balık, H. Yanık, B. A. Urgen, and M. G. Veldhuizen, “Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation Effects on Flavor‐Evoked Electroencephalogram and Eye‐Blink Rate,” Brain and Behavior, vol. 15, no. 3, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.70355.

- Q. Zhao, P. Yang, X. Wang, Z. Ye, Z. Xu, J. Chen, S. Chen, X. Ye, and H. Cheng, “Unveiling brain response mechanisms of citrus flavor perception: An EEG-based study on sensory and cognitive responses,” Food Research International, vol. 206, pp. 116096–116096, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2025.116096.

- J. Liu, Y. Xu, X. Lian, T. Liu, H. Ning, X. Jiang, S. Yu, S. Liu, L. Huang, X. Sun, J. Li, and D. Xu, “A comprehensive framework for decoding salty taste information from electroencephalography signals: distinguishing brain reactions to saltiness of comparable intensity,” Food Science and Human Wellness, vol. 14, no. 4, p. 9250099, 2025, https://doi.org/10.26599/fshw.2024.9250099.

- L. Stickel, S. Poggesi, K. G. Grunert, L. Lähteenmäki, and J. Hort, “Do you remember? Consumer reactions to health-related information on snacks in repeated exposure,” Food Quality and Preference, pp. 105431–105431, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2025.105431.

- X. Wang, G. Wang, and D. Liu, “EEG-Based Analysis of Neural Responses to Sweeteners: Effects of Type and Concentration,” Foods, vol. 14, no. 14, pp. 2460–2460, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14142460.

- S. De, P. Mukherjee, and A. H. Roy, “TasteNet: A novel deep learning approach for EEG-based basic taste perception recognition using CEEMDAN domain entropy features,” Journal of Neuroscience Methods, vol. 419, p. 110463, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2025.110463.

- G. Wang, X. Wang, T. Zhang, Z. Qin, F. Zheng, X. Ye, B. Sun, and H. Cheng, “Advancing flavor perception research with EEG microstate analysis: A dynamic approach to understanding brain responses to alcoholic stimuli,” Food Chemistry, pp. 144218–144218, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2025.144218.

- Q. Wang et al., “Mechanistic study of saltiness enhancement induced by three characteristic volatiles identified in Jinhua dry-cured ham using electroencephalography (EEG),” Food Chemistry, pp. 144180–144180, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2025.144180.

- H. Park et al., “Elucidation of chemosensory and neurophysiological approaches of rice (Oryza sativa L.) bran foods with sugar substitutes through permutation and machine learning-assisted screening methods,” Food Bioscience, vol. 71, p. 107090, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2025.107090.

- J. Yang, J. Zhang, J. Xu, Q. Ke, X. Kou, and X. Huang, “SensoryGAN: AI-driven design of low-toxicity dairy flavor alternatives with integrated neurosensory and cellular safety validation,” Food Research International, vol. 218, pp. 116785–116785, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2025.116785.

- D. R. Pereira, H. R. Pereira, M. L. Silva, P. Pereira, and H. A. Ferreira, “Impact of five basic tastes perception on neurophysiological response: Results from brain activity,” Food Quality and Preference, vol. 131, p. 105572, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2025.105572.

- P. Chen et al., “Electroencephalography (EEG) design for flavor perception of Baijiu: An investigation into the influence of full-bodied mouthfeel on brain rhythms,” Food Chemistry, pp. 145864–145864, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2025.145864.

- Y. Fu et al., “Neurophysiological and multimodal sensory evaluation of baijiu and food pairing liking,” Food Research International, pp. 117451–117451, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2025.117451.

- X. Wang and L. Guoce, “TEDNet: Cascaded CNN-Transformer with Dual Attentions for Taste EEG Decoding,” Journal of Neuroscience Methods, vol. 424, pp. 110594–110594, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2025.110594.

Yuri Pamungkas (Advances in Brain-Computer Interfaces for Taste Perception: Current Insights and Future Directions)