ISSN: 2685-9572 Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro

Vol. 8, No. 1, February 2026, pp. 222-240

Artificial Intelligence and IoT for Riverine Oil Spill Detection: A Focused Review and Proposed Adaptive Edge Framework

Shireen M. AL-Khafaji, Hikmat N. Abdullah

Department of Information and Communications Engineering, College of Information Engineering, Al-Nahrain University, Jadriya, Baghdad, Iraq

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 08 September 2025 Revised 14 December 2025 Accepted 10 February 2026 |

|

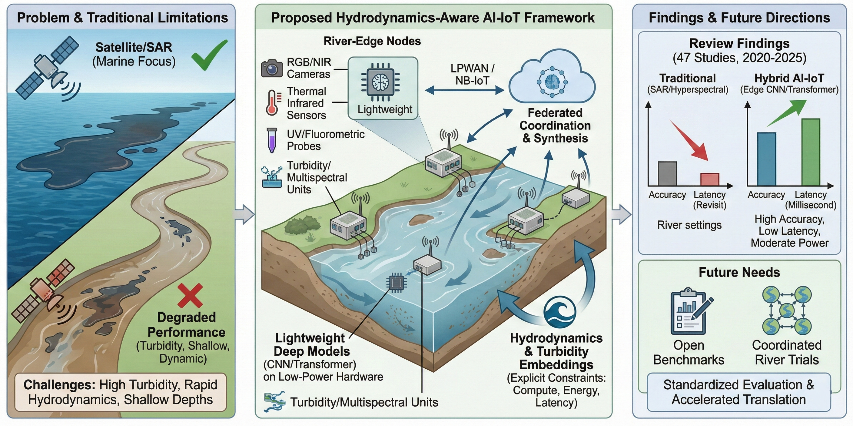

Riverine oil spills are more challenging to detect than marine spills due to shallow depths, high turbidity, and rapidly changing hydrodynamics, which degrade the performance of satellite- and SAR-based detection methods. This review examines how artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things can deliver accurate, low-latency detection in freshwater and defines an AI-IoT system as distributed river-edge nodes with RGB/NIR cameras, thermal infrared sensors, UV/fluorometric probes, and turbidity/multispectral units running lightweight deep models on low-power hardware and networked via LPWAN or NB-IoT with optional federated coordination. The novel contribution is a hydrodynamics-aware, adaptive framework that embeds river flow and turbidity, couples explicit constraints on edge compute, energy, and inference latency, and derives multi-sensor fusion logic from comparative synthesis. Performance is organized along accuracy, decision latency, deployment cost, and environmental adaptability. Using a structured narrative review with scoping elements, the research screened 145 records from major databases. It synthesized 47 peer-reviewed studies (2020-2025), harmonized definitions, and applied descriptive synthesis to manage heterogeneous metrics and protocols. Results show that SAR and hyperspectral methods that excel in marine or controlled settings often degrade in narrow, turbid rivers because of clutter and revisit latency. In contrast, hybrid AI-IoT architectures employing compact CNN/Transformer variants at the edge report high accuracy with millisecond-scale inference and moderate power budgets. Limitations include heterogeneous reporting, non-standard datasets, and limited multi-site validation. The framework and synthesis motivate open benchmarks and coordinated river trials to standardize evaluation and accelerate translation. |

Keywords: Freshwater Monitoring; Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR); Multi-Sensor Data Fusion; Federated Learning; Hyperspectral Imaging |

Corresponding Author: Shireen M. AL-Khafaji1, Department of Information and Communications Engineering, Al-Nahrain University Baghdad, Iraq. Email: shireen.migsid@coie-nahrain.edu.iq |

This work is open access under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: S. M. AL-Khafaji and H. N. Abdullah, “Artificial Intelligence and IoT for Riverine Oil Spill Detection: A Focused Review and Proposed Adaptive Edge Framework,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 222-240, 2026, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v8i1.14677. |

- INTRODUCTION

Oil spills constitute severe environmental disasters, originating from human activities that release petroleum hydrocarbons into natural water systems [1][2]. These incidents typically result from exploration, transportation, and refining activities, with tanker accidents alone accounting for an estimated 5.86 million tons of oil globally [3]. Reducing the environmental impact of such accidents critically depends on early and accurate detection. Rivers present a particular challenge compared to marine environments. Unlike oceans and seas, rivers exhibit dynamic hydrodynamic behaviour, including strong currents, turbulence, shallow depths, debris, and confined channel geometries that severely hamper conventional oil detection and containment efforts [4][5]. Spills can spread swiftly, travelling hundreds of kilometres from the source and forming fragmented or submerged oil layers that are difficult to track [6].

Conventional monitoring has predominantly relied on manual sampling and satellite remote sensing. Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) and related satellite-based methods enable large-scale surveillance, yet they encounter significant limitations in riverine settings [7]-[9]. In narrow channels, satellite imagery suffers from insufficient spatial resolution, and the latency of satellite passes fails to capture rapid downstream transport. In addition, high turbidity, vegetation, and complex backgrounds in inland waters frequently lead to misclassification, in which natural features or look-alikes are mistaken for oil films [10]-[12]. Comparative studies further show that models calibrated on open-ocean imagery often degrade when applied to narrow, turbid waterways, highlighting a performance gap between marine-optimized and riverine detection systems in terms of accuracy, latency, and operational reliability [13].

Recent advances in the Internet of Things (IoT) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) offer alternative approaches to these constraints. IoT-based sensing networks employing thermal, optical, fluorometric, and other advanced sensors are increasingly utilized for high-frequency in-situ water monitoring .AI algorithms such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Vision Transformers (ViTs), and other deep architectures are applied to remote-sensing and in-situ data for oil spill detection and related environmental assessment [14]-[17]. A recent YOLOv11-driven model that integrates multispectral UAV imaging with multi-scale feature fusion and attention mechanisms (YOLO-ADHF-SimAM) has demonstrated that lightweight UAV-AI systems can achieve high precision and robust mAP performance for inland lake oil spill detection, even under turbid water and vegetation occlusion. This confirms the feasibility of real-time, edge-oriented monitoring in complex inland waters [18]. Unlike satellite-based platforms, IoT nodes provide continuous local measurements, and AI models can capture non-linear patterns arising from turbidity, clutter, and dynamic flow, making AI-IoT architectures particularly suitable for riverine environments.

AI-IoT integration further enables edge computing, where detection decisions are made close to the sensors, reducing communication delays and enabling adaptation to local flow dynamics [19]-[21]. These capabilities indicate that AI-IoT architectures are well-positioned to complement or surpass traditional marine-optimized technologies for riverine spill detection, particularly when performance is evaluated across multiple criteria, including detection accuracy, decision latency, deployment cost, and adaptability to changing hydrodynamic and optical conditions.

Despite these technological advances, a critical gap remains in the literature. Many studies treat sensing systems and algorithmic analysis in isolation or rely on models trained primarily on marine datasets that do not generalize well to freshwater environments [13],[22][ 23]. Operational limitations persist where turbulent flow displaces oil plumes beyond fixed sensor ranges [24], and data privacy or governance concerns restrict the sharing of large-scale datasets needed to train robust deep learning models [25][26]. Furthermore, reported performance metrics are heterogeneous and rarely jointly evaluate accuracy, latency, cost, and adaptability under realistic riverine conditions [7]. Improving robustness under such variable conditions requires a unified framework that combines advanced data-fusion techniques, adaptive learning algorithms including federated and generative approaches, and hydrodynamic knowledge of spill transport [27][28]. Consequently, this paper pursues two distinct objectives:

- Systematic Review: To critically evaluate how traditional, AI-based, and hybrid technologies compare regarding accuracy, latency, and adaptability in freshwater environments [29].

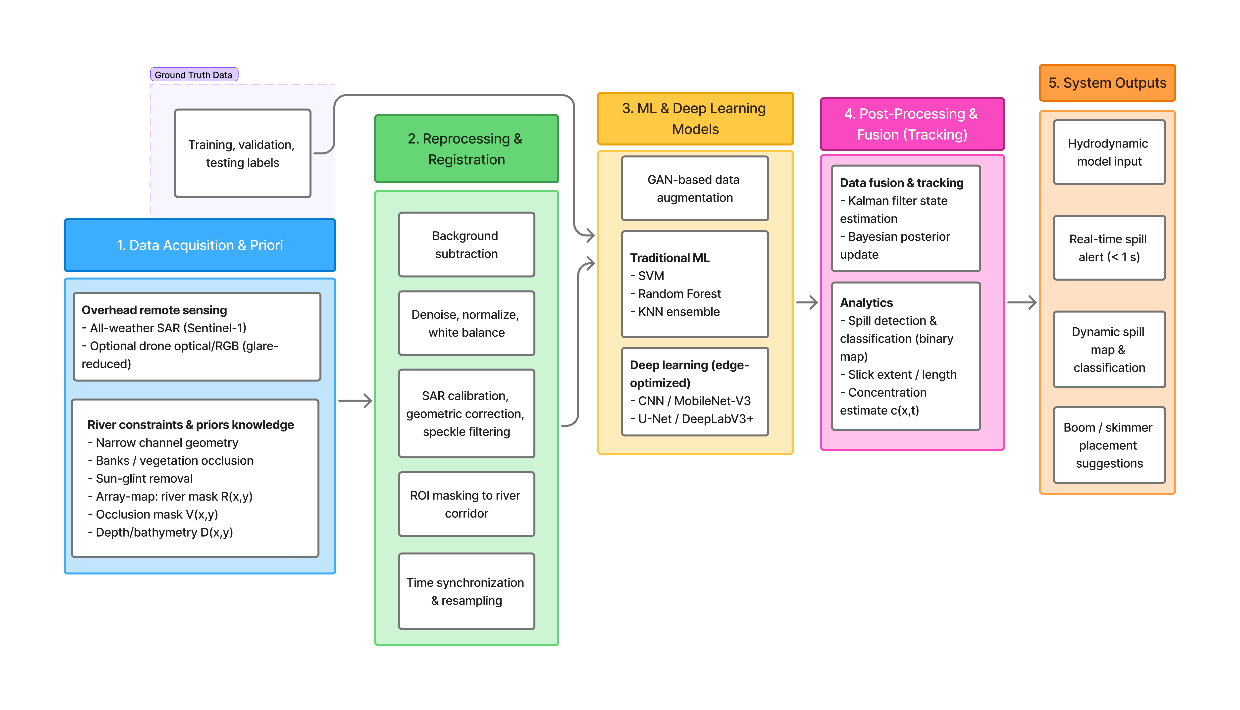

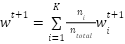

- Conceptual Proposal: To formulate a novel Adaptive AI-IoT Framework that integrates remote and in-situ sensing [30]-[34]. This framework is not an arbitrary design but is derived directly from the limitations identified in the review, explicitly addressing the need for hydrodynamic masking [24], edge computing [21], and privacy-preserving Federated Learning [28],[35] in riverine monitoring, as schematically illustrated in Figure 1.

Based on the above objectives, the research contributions are (i) a river-focused comparative review across four axes (accuracy, latency, cost, and adaptability); and (ii) a hydrodynamics-aware, adaptive AI-IoT framework derived from the identified limitations, as detailed in Section 5. To address these objectives, the remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 characterizes riverine spill dynamics and reviews conventional and emerging detection modalities. Section 3 details the review methodology, including databases, screening protocol, and performance criteria. Section 4 synthesizes the evidence in a comparative analysis of technological and algorithmic options. Section 5 proposes the adaptive, hydrodynamics-aware AI-IoT framework and discusses implementation considerations for sensor nodes, edge compute, and multi-sensor fusion. Section 6 concludes with key findings, limitations, and prioritized directions for future research.

Figure 1. Framework for riverine oil-spill detection

- MATERIALS AND METHODS

This section describes the methodological approach used to identify, select, and analyze the literature on riverine oil spill detection technologies. It details the review design, database search strategy, screening and eligibility procedures, data extraction and synthesis protocol, and the process by which the adaptive AI-IoT framework was derived from the assembled evidence base.

- Research Methodology

This study adopts a structured narrative review with elements of a scoping review. The methodology enables a qualitative appraisal of heterogeneous technologies, such as satellite radar, unmanned aerial vehicles, in-situ IoT sensors, and AI-based classifiers. It supports the derivation of an integrated, adaptive framework. The methodology follows four main phases: (1) identification of relevant literature using structured Boolean search strings; (2) screening and eligibility assessment based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria; (3) data extraction and comparative synthesis of performance and operational metrics; and (4) formulation of an adaptive AI-IoT framework grounded in the identified gaps and limitations [36].

- Search Strategy, Study Selection, and Inclusion Criteria

A systematic search was conducted in IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection, and ScienceDirect for publications between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2025, a period chosen to capture the emergence of Vision Transformers and edge-native AI. A structured Boolean query, applied to titles, abstracts, and keywords, combined oil-spill terms, riverine terms, and AI/IoT terms; a representative form was (oil spill detection OR hydrocarbon sensing) AND (river OR freshwater OR inland water) AND (artificial intelligence OR deep learning OR IoT OR edge computing).

Where supported, subject-area filters were used to restrict results to environmental science, remote sensing, computer science, and electrical engineering. Google Scholar served solely as a secondary source to identify grey literature and recent preprints not yet indexed, accounting for less than 5% of the final set of included studies.

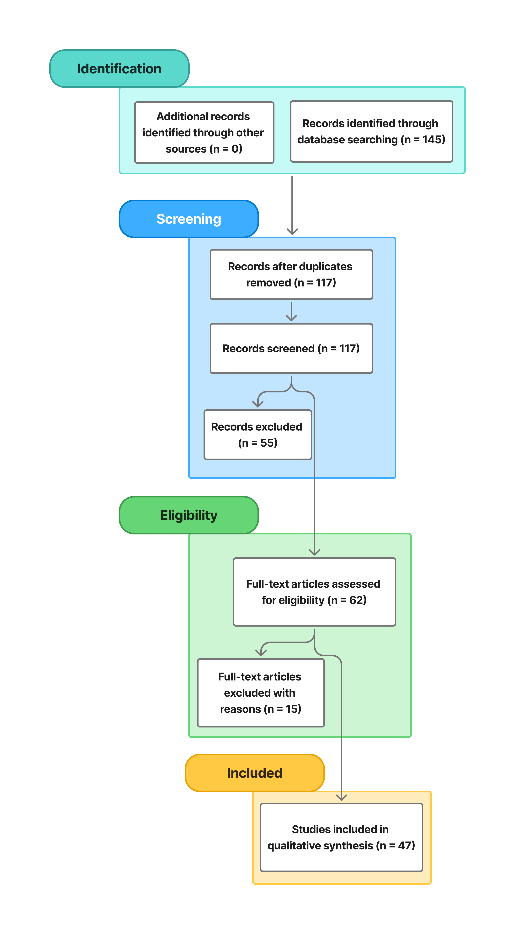

The initial search returned 145 records. After removing 28 duplicates, 117 unique records underwent title-abstract screening. Studies were included if they: (1) were peer-reviewed journal articles or full conference papers in English; (2) addressed oil, hydrocarbon, or closely related surface-water contamination in riverine, lake, reservoir, estuarine, or other freshwater environments, or presented marine methods whose formulation and evaluation were explicitly transferable to riverine contexts; (3) employed remote sensing, in-situ or IoT-based sensing, or combined sensing architectures; (4) used artificial intelligence, machine learning, deep learning, algorithmic data fusion, or clearly specified architectures relevant to AI-IoT integration; and (5) reported at least one quantitative or operational metric relevant to detection. Editorials and policy papers without technical detail, studies focused exclusively on open-ocean spills, purely numerical trajectory models without sensing components, short abstracts or theses lacking methodological description, non-English publications, and duplicate or superseded versions were excluded. Application of these criteria resulted in a final group of 47 eligible studies.

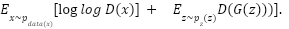

- Screening and Quality Appraisal (PRISMA Workflow)

Title and abstract screening yielded 62 articles for full-text review, of which 47 met the final eligibility threshold and formed the core evidence base. The selection process is summarized in the PRISMA-style flow diagram in Figure 2, which reports the numbers of records identified, screened, excluded at each stage, and retained for synthesis. Methodological quality and risk of bias were qualitatively appraised for each included study across five aspects: clarity and reproducibility of the sensing and algorithmic pipeline; adequacy of the ground truth and validation strategy; sample size and environmental diversity; transparency of evaluation metrics and numerical results; and explicit acknowledgement of limitations and failure modes. Each aspect was rated as strong, moderate, or weak. These ratings informed the interpretive weight assigned to individual results in the synthesis but were not used as complex exclusion criteria.

Figure 2: PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process for riverine oil spill detection studies

- Data Extraction and Comparative Synthesis

A standardized extraction template was used for all included studies. Extracted variables encompassed environmental setting; sensing modality and platform; algorithmic approach; system architecture (standalone remote sensing, in-situ IoT network, edge cloud hierarchy, federated configuration); dataset characteristics and ground truth; and performance and operational metrics.

Key concepts were coded using harmonized operational definitions. Detection accuracy was recorded as the primary accuracy metric reported in each study, with explicit notation indicating whether it corresponded to mean average precision, F1-score, intersection-over-union, overall accuracy, or a related measure. Latency denotes the time between data acquisition and the availability of a detection decision. It was either extracted numerically or categorized into sub-second, second, minute, and longer-than-hour classes when only qualitative descriptions were available. Deployment cost referred to direct sensing and computing hardware expenditure and was coded qualitatively as low, medium, or high based on relative platform requirements (for example, satellite imagery subscription versus low-cost embedded hardware). Adaptability was captured as robustness to variations in turbidity, flow velocity, illumination, and background clutter. It was coded on an ordinal scale (low, medium, high) based on the range of conditions tested and the presence of explicit robustness analysis.

Because of substantial heterogeneity in datasets, evaluation protocols, and reported metrics, formal meta-analysis was not appropriate. Instead, a descriptive and comparative synthesis was undertaken. Studies were grouped into three clusters: remote sensing, in-situ IoT sensing, and hybrid AI-IoT architectures. Performance, latency, cost, and adaptability were summarized as literature-based ranges rather than pooled estimates. Conflicting or anomalous findings were documented explicitly, with particular attention to conditions under which methods degraded or failed.

- Quantitative Synthesis and Handling of Heterogeneity

The substantial heterogeneity in evaluation protocols, the use of divergent Intersection-over-Union thresholds, and the use of varying hardware platforms for latency testing precluded the execution of a statistical meta-analysis. Consequently, a descriptive best-evidence synthesis was employed. The performance ranges presented in the Results section, specifically in Table 4 and Table 5, constitute the envelope of peak performance derived from the eligible studies.

- Accuracy: The specified ranges define the interval extending from the lowest to the highest optimal F1-scores or mean Average Precision values documented in peer-reviewed trials. Outliers lacking rigorous cross-validation were excluded to maintain data reliability.

- Latency: Inference times were categorized according to hardware class, such as distinguishing between standard single-board computers and GPU-accelerated edge devices, such as Raspberry Pi vs. Jetson Nano, to ensure valid comparability.

- Interpretation: These ranges represent the technical capability of current state-of-the-art models under controlled experimental conditions rather than a statistical mean of performance across all operational field deployments.

- Framework Design Procedure

The final phase translated recurrent limitations identified in the synthesis into a conceptual design for an adaptive AI-IoT framework. Key shortcomings, such as satellite revisit latency, poor transfer of marine-trained models to riverine domains, data scarcity and privacy constraints for riverine datasets, and energy and connectivity limitations of in-situ nodes, were mapped to methodological opportunities in federated learning for privacy-preserving training [37], edge computing for low-latency inference [21], and multimodal fusion for robustness under turbid and cluttered conditions [11]. The resulting hydrodynamics-aware framework, presented in Section 5, combines the most promising sensing modalities and algorithmic components identified in the review and is proposed as a logically derived response to the gaps and trade-offs revealed by the comparative analysis.

- RESULT AND DISCUSSION

This section presents the synthesized results of the literature review and an integrated discussion of how existing technologies perform for riverine oil spill detection. The review evaluates systems against four joint criteria: detection accuracy, decision latency, deployment cost, and environmental adaptability. The analysis first distils the study’s principal findings, then situates them relative to prior work, interprets their implications and underlying mechanisms, and concludes with a balanced appraisal of strengths and limitations.

- Main Findings of the Present Study

This subsection synthesizes the key outcomes of the reviewed studies, highlighting how riverine hydrodynamics, sensing technologies, and AI-IoT integration collectively influence oil spill detection performance. It distils the main evidence-based patterns in accuracy, latency, cost, and adaptability that underpin the subsequent discussion.

- Riverine Spill Dynamics

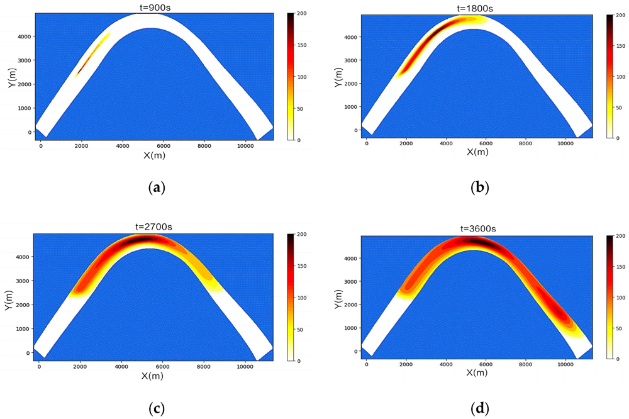

Oil behavior in rivers is consistently shown to be governed by hydrodynamic and physicochemical processes that differ markedly from those in marine environments [2]. Swift longitudinal currents, turbulence, shallow depths, and confined channel geometries accelerate downstream advection and limit lateral spreading [6],[24]. As illustrated in Figure 3, a representative hydrodynamic simulation of an oil spill in a curved river reach (0-3600 s) demonstrates that channel curvature and secondary currents concentrate slicks along the outer bend, increasing downstream dispersion by about 30-40% relative to an equivalent straight reach due to locally elevated velocities and turbulent kinetic energy [5]. The key hydrodynamic parameters influencing this behavior are synthesized in Table 1, which compiles typical ranges of flow velocity, TKE, suspended sediment concentration, water temperature, and oil viscosity from recent river-focused studies [38] . These ranges ( ≈ 0.2-2.5 m/s,

≈ 0.2-2.5 m/s,  ≈ 0.001-0.2 m²/s²,

≈ 0.001-0.2 m²/s²,  ≈ 10-800 mg/L, temperature ≈ 5-35 °C, viscosity ≈ 5-200 cP) highlight substantial spatial and seasonal variability and explain why oil may appear as thin surface films, submerged oil-particle aggregates in turbid flow, or residues attached to shorelines and vegetation [7] . Overall, the main hydrodynamic conclusion is that riverine spills are more dynamic, heterogeneous, and localized than marine spills, making static or low-frequency monitoring particularly prone to missed detection

≈ 10-800 mg/L, temperature ≈ 5-35 °C, viscosity ≈ 5-200 cP) highlight substantial spatial and seasonal variability and explain why oil may appear as thin surface films, submerged oil-particle aggregates in turbid flow, or residues attached to shorelines and vegetation [7] . Overall, the main hydrodynamic conclusion is that riverine spills are more dynamic, heterogeneous, and localized than marine spills, making static or low-frequency monitoring particularly prone to missed detection

Figure 3. Simulated oil spill dispersion in a curved river channel over one hour (0-3600 s) [5]

Table 1. Key hydrodynamic parameters influencing oil behavior in riverine systems [5],[43]

Parameter | Influence on Oil Behavior | Typical Range |

Flow velocity (U) [m/s] | Controls advection rate | 0.2- 2.5 |

Turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) [m²/s²] | Promotes vertical mixing | 0.001- 0.2 |

Sediment concentration (Cs) [mg/L] | Enhances oil particle aggregation (OPA) | 10 - 800 |

Water temperature (°C) | Affects evaporation and emulsification | 5 - 35 |

Oil viscosity (cP) | Governs the spreading and weathering rate | 5 - 200 |

- Detection Technologies: Traditional Vs. Emerging Approaches

The synthesized body of literature evidences a pronounced shift from conventional, manual-intensive monitoring practices toward automated, AI- and IoT-enabled architectures for riverine oil spill detection [5],[7],[13],[19],[22],[39]. As summarized in Table 2, traditional approaches encompassing visual patrols, grab sampling with subsequent laboratory analysis, and standalone optical or SAR remote sensing remain operationally relevant, yet are characterized by delayed detection, localized and intermittent spatial-temporal coverage, strong dependence on human operators, and substantial recurrent labour requirements [29],[40]. In contrast, emerging AI-IoT and hybrid systems integrate multi-sensor data streams from satellite, UAV, and in-situ sensor networks with edge and cloud analytics to support near real-time, largely autonomous detection and alert generation [13]-[17],[19],[21]. The comparative profiles reported in Table 2, derived from these studies, indicate that although such architectures entail higher initial investments in sensing, communication, and computational infrastructure, they deliver marked improvements in detection speed, spatial and temporal coverage, environmental adaptability, and scalability by reducing routine human intervention and enabling continuous multi-site monitoring in hydrodynamically dynamic riverine environments.

Table 2. Comparison between traditional and AI-IoT-based oil spill detection approaches in riverine environments.

Aspect | Traditional Approaches | Emerging Approaches (AI-IoT, Hybrid) |

Primary techniques | Visual patrols, manual sampling, laboratory testing, and standalone optical/SAR remote sensing | AI-based image analysis, in-situ IoT sensing, edge and cloud analytics |

Data source | Physical water samples, visual observation, single-sensor imagery | Multi-sensor fusion (satellite, UAV, in-situ), continuous environmental data streams |

Detection speed | Delayed; dependent on sample collection, transport, and laboratory processing | Near real-time; autonomous detection through on-board and edge AI inference |

Spatial/temporal coverage | Localized and intermittent; periodic field campaigns or satellite overpasses | Continuous monitoring; scalable to multiple rivers reaches and critical sites |

Accuracy and precision | High in laboratory conditions, but prone to sampling and observer error in the field | Highly underwell-trained models; adaptive to noise, clutter, and changing conditions |

Human involvement | Extensive manual sampling, inspection, and result interpretation | Minimal routine intervention; automated acquisition, processing, and alerting |

Cost and infrastructure | Low-moderate equipment cost; high recurring labor and operational effort | Moderate-high initial deployment cost; reduced marginal cost and labor at scale |

Environmental adaptability | Sensitive to weather, lighting, access constraints, and operator availability | Improved robustness under variable flow, turbidity, and illumination; suitable for dynamic rivers |

Scalability and integration | Limited scalability; largely isolated instruments and datasets | Highly scalable; integrates heterogeneous sensors, AI models, and cloud/edge platforms |

Typical limitations | Slow response, low automation, sparse coverage, limited real-time capability | Requires computational resources, reliable power, and communication connectivity |

- AI-Driven Sensing, Data Fusion, and Model Performance

Modern riverine oil spill detection increasingly employs multi-source data fusion and advanced AI models to reconcile heterogeneous observations under strongly variable hydrodynamic and optical conditions. Several studies combine SAR imagery, UAV-based hyperspectral or thermal data, and in-situ IoT measurements, including chemical, optical, water-quality, and water-level sensors, to construct an integrated representation of river state [8],[11],[22],[31],[32] . Representative specifications of low-cost IoT sensors suitable for real-time riverine monitoring are summarised in Table 3, highlighting the diversity of measured parameters and communication protocols that can be exploited within AI-IoT frameworks.

Table 3. Specifications of IoT Sensors for Real-Time Riverine Monitoring

Sensor Type | Parameter Monitored | Typical Range/Accuracy | Communication Protocol |

Optical Camera | Visual imagery | High-resolution; 224×224 pixels | Wi-Fi / Zigbee |

Chemical Sensor | Hydrocarbon concentration | ppm scale; ±5% accuracy | LoRaWAN / NB-IoT |

Water Quality Sensor | Temperature, pH, DO | Temperature: -40°C to 85°C | MQTT |

Ultrasonic Sensor | Water level | Range: 0 4 m; ±1% accuracy | Zigbee / Wi-Fi |

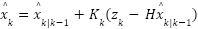

Within such architectures, data fusion is typically formulated using state-estimation and probabilistic frameworks. In Kalman-based fusion [41], the a priori (predicted) state estimate at time step  denoted

denoted  (equivalently

(equivalently  ), is updated to the a posteriori (corrected) estimate

), is updated to the a posteriori (corrected) estimate  or

or  after assimilating a new observation

after assimilating a new observation  according to (1):

according to (1):

|

| (1) |

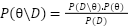

where  is the Kalman gain and 𝐻 is the observation matrix [29]. Complementarily, Bayesian fusion [42] refines the posterior belief over the environmental state

is the Kalman gain and 𝐻 is the observation matrix [29]. Complementarily, Bayesian fusion [42] refines the posterior belief over the environmental state  given data

given data  Via (2):

Via (2):

|

| (2) |

which provides a principled mechanism for combining heterogeneous sensor streams while explicitly accounting for uncertainty. Across the reviewed studies, application of the formulations in (1) to (2) to combined SAR, UAV, and IoT datasets has been reported to reduce false positives and yield more stable detection performance in turbid, cluttered river reaches when compared with single-sensor baselines [22],[24].

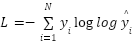

At the algorithmic level, deep learning models constitute the analytical core of next-generation systems. Architectures such as ResNet, DeepLabv3+, Vision Transformers (ViT), and YOLO variants have been deployed for oil-non-oil discrimination and spill localization on SAR, optical, and hyperspectral imagery [8],[15],[18],[43][44]. Supervised training typically minimizes the categorical cross-entropy loss [45] in (3):

|

| (3) |

where  and

and  denote the actual label and predicted probability for class i, respectively. Due to the limited availability of labelled riverine datasets, transfer learning is widely adopted; models pre-trained on large-scale image corpora are fine-tuned on domain-specific datasets such as inland-water oil imagery, which improves generalization under scarce annotations [5],[17].

denote the actual label and predicted probability for class i, respectively. Due to the limited availability of labelled riverine datasets, transfer learning is widely adopted; models pre-trained on large-scale image corpora are fine-tuned on domain-specific datasets such as inland-water oil imagery, which improves generalization under scarce annotations [5],[17].

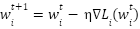

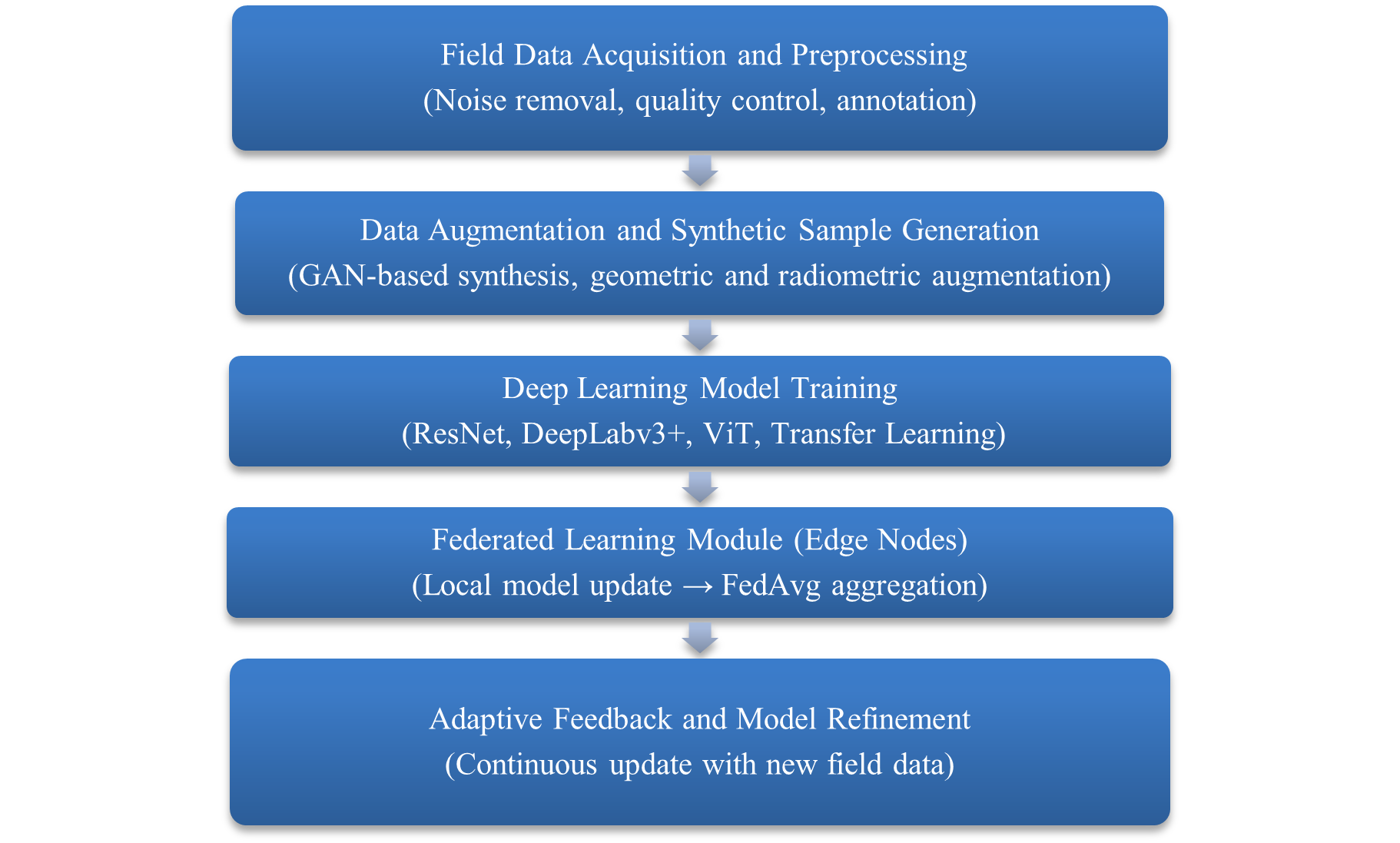

To address data privacy constraints and distributional heterogeneity across geographically dispersed monitoring sites, several environmental sensing studies utilise Federated Learning (FL) frameworks [25],[27][28],[35]. In FL, each local node ii updates its model parameters  a stochastic gradient descent [46], as in (4):

a stochastic gradient descent [46], as in (4):

|

| (4) |

Where  is the learning rate and

is the learning rate and  is the local loss function. A central server then aggregates the local updates using Federated Averaging (5):

is the local loss function. A central server then aggregates the local updates using Federated Averaging (5):

|

| (5) |

with  denoting the number of samples at the client

denoting the number of samples at the client  and

and  Figure 4 conceptually summarizes this self-evolving learning loop: IoT nodes perform local training using (4), an edge-cloud or cloud server aggregates and updates a global model using (5), and refined parameters are periodically redeployed to the edge. This workflow allows detection models to adapt to seasonal turbidity changes, evolving background patterns, and sensor drift, while avoiding transmission of raw data and thereby preserving privacy and reducing bandwidth demands.

Figure 4 conceptually summarizes this self-evolving learning loop: IoT nodes perform local training using (4), an edge-cloud or cloud server aggregates and updates a global model using (5), and refined parameters are periodically redeployed to the edge. This workflow allows detection models to adapt to seasonal turbidity changes, evolving background patterns, and sensor drift, while avoiding transmission of raw data and thereby preserving privacy and reducing bandwidth demands.

Despite these methodological advances, data scarcity and class imbalance remain central challenges, particularly for rare or extreme spill configurations. To mitigate these limitations, several works employ Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to augment oil spill datasets synthetically [47][48] .The standard GAN minimax objective [49] in (6),

|

| (6) |

Pits a generator G, which produces synthetic samples from noise z, against a discriminator D, which distinguishes real from generated data. For oil spill imagery, GAN-based augmentation has been reported to increase robustness under rare conditions such as thin surface sheens, highly turbid water, and complex background clutter, with improvements of several percentage points in F1-score or mean average precision relative to training without synthetic samples [48]. Taken together, multi-source fusion as formalized in (1) and (2), deep learning optimization in (3), FL-based distributed training in (4) to (5), and GAN-based augmentation in (6) form a coherent methodological toolkit that directly addresses the heterogeneity, non-stationarity, and data limitations documented in the literature, thereby enabling more reliable and adaptive riverine oil spill detection than static or single-sensor approaches.

Figure 4. Conceptual workflow of the self-evolving deep learning framework for oil spill detection

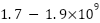

- Edge Computing and Inference Performance

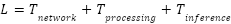

Edge computing places inference close to the data source, reducing end-to-end latency and decreasing reliance on high-bandwidth, low-latency communication links. The total detection latency 𝐿 [50] for a sensing node expressed as in (7):

|

| (7) |

where  denotes communication time,

denotes communication time,  denotes pre-inference signal or image processing, and

denotes pre-inference signal or image processing, and  denotes model execution time [21],[26]. Deploying lightweight AI models on embedded platforms such as Raspberry Pi and NVIDIA Jetson Nano allows local analysis of camera or sensor data and the generation of alerts, substantially reducing

denotes model execution time [21],[26]. Deploying lightweight AI models on embedded platforms such as Raspberry Pi and NVIDIA Jetson Nano allows local analysis of camera or sensor data and the generation of alerts, substantially reducing  and enabling near real-time decision-making under intermittent connectivity conditions [17],[44],[47][48],[51],[58], accuracies for these models range from approximately 90-92% for compact architectures such as MobileNet-V3 to 97-98% for ViT-B/16 on domain-specific downstream tasks under controlled conditions. Corresponding single-image inference times on edge-class hardware typically range from 10-20 ms for lightweight models such as YOLOv8-nano and ResNet-50, and from 55-70 ms for ViT-B/16. Reported model sizes extend from roughly 12-25 MB for MobileNet-V3 and YOLOv8-nano to approximately 320-340 MB for ViT-B/16, with FLOPs typically spanning

and enabling near real-time decision-making under intermittent connectivity conditions [17],[44],[47][48],[51],[58], accuracies for these models range from approximately 90-92% for compact architectures such as MobileNet-V3 to 97-98% for ViT-B/16 on domain-specific downstream tasks under controlled conditions. Corresponding single-image inference times on edge-class hardware typically range from 10-20 ms for lightweight models such as YOLOv8-nano and ResNet-50, and from 55-70 ms for ViT-B/16. Reported model sizes extend from roughly 12-25 MB for MobileNet-V3 and YOLOv8-nano to approximately 320-340 MB for ViT-B/16, with FLOPs typically spanning  for MobileNet-V3, about

for MobileNet-V3, about  for ResNet-50, around

for ResNet-50, around  for EfficientNet-B3, and

for EfficientNet-B3, and  for ViT-B/16, while YOLOv8-nano operates in the

for ViT-B/16, while YOLOv8-nano operates in the  range. These values indicate a consistent accuracy-efficiency trade-off: architectures suitable for ultra-low-power IoT nodes tend to offer slightly lower peak accuracy than large transformer-based models, but provide substantially lower latency and computational demand, which are essential for continuous edge-based monitoring in riverine environments.

range. These values indicate a consistent accuracy-efficiency trade-off: architectures suitable for ultra-low-power IoT nodes tend to offer slightly lower peak accuracy than large transformer-based models, but provide substantially lower latency and computational demand, which are essential for continuous edge-based monitoring in riverine environments.

The discussion of Table 4 is based on literature-derived ranges rather than a single unified benchmark. Accuracy values correspond to minimum-maximum results reported for downstream oil spill or environmental monitoring tasks using the respective architectures. At the same time, FLOPs and model sizes follow standard ImageNet-scale classifier configurations at 224 × 224 pixels for MobileNet-V3 Large, ResNet-50, EfficientNet-B3, and ViT-B/16, and the canonical 640 × 640 detection configuration for YOLOv8-nano. Inference times reflect single-image forward passes on representative edge-class CPUs and GPUs, such as Jetson-class devices, and should therefore be interpreted as indicative envelopes rather than device-specific guarantees. Results obtained with atypical input resolutions, aggressive quantization, or specialized accelerators were not used to define the central ranges to limit bias from outliers. Under these assumptions, the Table 4 is intended to characterize relative trade-offs between accuracy and efficiency, and suitability for edge deployment, rather than to provide exact, directly comparable benchmarks across all architectures.

Table 4. Comparative Performance of Deep Learning Models for Oil Spill Detection (Edge Deployment Suitability).

AI Model | Accuracy (%) | Inference Time (ms) | Model Size (MB) | FLOPs ( ) ) | Edge Deployment Suitability | Remarks |

MobileNet-V3 [44],[52] | 90-92 | 20-35 | 20-25 | 0.2-0.25 | Very High | Ideal for low-power IoT nodes; fastest inference with modest accuracy. |

YOLOv8-nano [54],[58] | 94-95 | 10-20 | 12-15 | 8-9 | Very High | Optimized for embedded inference; effective for small-scale spill detection. |

ResNet-50 [51],[55] | 95-96 | 20-35 | 95-105 | 4.0-4.2 | Moderate | Balanced accuracy but heavier than mobile-optimized nets; widely adopted in SAR. |

EfficientNet-B3 [59],[56] | 96-97 | 25-40 | 45-55 | 1.8-1.9 | Moderate | Excellent accuracy but requires greater memory and computing resources. |

Vision Transformer (ViT-B/16) [53],[57] | 97-98 | 55-70 | 320-340 | 17-18 | Low | High precision but computationally heavy; suited to cloud or GPU processing. |

The latency patterns implied by Table 4 are illustrated in Figure 5, which shows that models such as YOLOv8-nano and ResNet-50 typically achieve inference times in the 10-20 ms range on edge hardware, allowing frame-by-frame analysis close to real-time. In contrast, ViT-B/16 often exhibits latencies above 50 ms per frame, making it more appropriate for low-frequency or batch-processing scenarios. From an energy perspective, dynamic power consumption 𝐸 scales approximately with (8):

|

| (8) |

where C is the effective capacitance, V is the supply voltage, and f is the switching frequency. Higher FLOPs and longer inference times, therefore, translate into increased energy usage and reduced battery lifetime in remote deployments. Considered together, equation (7), the ranges synthesized in Table 4, and the latency profiles depicted in Figure 5 emphasize that resource-aware model selection is a critical design factor in riverine applications: compact convolutional networks and lightweight detectors are generally more appropriate for continuous, edge-based monitoring, whereas large transformer-based models are better positioned for cloud-side post-processing or offline analysis.

Figure 5. Median inference Latency of representative deep models on edge-class hardware, derived from Latency ranges reported in Table 4

- Comparative Performance and Technology Gaps

A consolidated view of the comparative performance of the reviewed technologies is provided in Table 5, which classifies detection approaches by cost level, adaptability, and reported detection accuracy over the 2020-2025 period. Cost levels are defined qualitatively to aid interpretation: low cost corresponds to basic equipment with minimal automation and typical per-site hardware expenditure below USD 1,000; moderate cost corresponds to multi-sensor or IoT-based systems with embedded computing in the approximate range of USD 1,000-10,000 per site; and high cost corresponds to specialized airborne or satellite sensors, or complex UAV-hyperspectral platforms, frequently exceeding USD 10,000 per unit. Accuracy intervals in Table 5 represent literature-derived ranges rather than pooled statistics, assembled from multiple experimental and field studies [5],[7],[8],[10],[13],[24],[46],[48]. Excessively high or low values reported under very narrow, highly controlled, or poorly documented conditions were treated as outliers. They were not used to define the central ranges when there was no corroboration. In cases where studies reported conflicting accuracies for a given technology, the tabulated range was chosen to encompass the majority of results obtained under comparable evaluation protocols, while recognizing the underlying heterogeneity in datasets, thresholds, and performance metrics.

The pattern emerging from this synthesis is that hybrid AI-IoT frameworks occupy the favorable region of the performance space, combining reported detection accuracies of 94-98% with high adaptability and moderate cost when built from off-the-shelf components [24],[53]. Traditional visual inspection and grab sampling fall at the low-cost end but show limited adaptability and lower field-level accuracy, typically around 60-85%, particularly in turbid or difficult-to-access river reaches. Thermal and infrared imaging exhibit moderate cost and accuracy (approximately 85-90%), whereas SAR achieves accuracies of about 88-94% yet remains constrained by relatively low adaptability in narrow, cluttered channels. Hyperspectral and UAV-based sensing provide high accuracies (approximately 90-96%) but at substantially higher capital and operational costs [8],[10][11],[46][47]. IoT sensor networks and standalone AI models occupy an intermediate position, with accuracies typically in the 88-97% range and generally high adaptability across river conditions [17],[21],[24],[53]. Taken together, the evidence indicates that integration and adaptivity rather than reliance on any single sensor modality are the primary drivers of superior performance in riverine oil spill detection.

Table 5. Summary of Detection Technologies by Cost, Adaptability, and Accuracy (2020- 2025)

Technology Type | Cost Level | Adaptability | Detection Accuracy (%) |

Visual / Manual Inspection [29],[5] | Low | Low | 60 -70 |

Grab Sampling / Laboratory [5][6] | Low Moderate | Moderate | 80 - 85 |

Thermal / Infrared Imaging [60],[10] | Moderate | Moderate | 85 - 90 |

SAR Imaging [8],[17] | High | Low | 88 - 94 |

Hyperspectral / UAV Sensing [60],[39],[23] | High | High | 90 - 96 |

IoT Sensor Networks [61] | Moderate | High | 88 - 93 |

AI / Deep Learning Models [19] | Moderate High | High | 92 - 97 |

Hybrid AI-IoT Frameworks [62] | Moderate | Very High | 94 - 98 |

- Comparison with Other Studies

The findings of the present synthesis are broadly consistent with, yet more focused explicitly than, several prior reviews on oil spill detection and environmental sensing. Keramea et al. [7] and Yekeen and Balogun [13] surveyed marine oil spill modelling and remote sensing and concluded that SAR and multispectral imagery, combined with machine-learning classifiers, can achieve high detection accuracies in offshore conditions. The accuracy ranges reported in those studies, typically on the order of 88-97 %, are in agreement with the performance ranges summarized for SAR and deep learning-based approaches in the current review. However, the assembled riverine evidence indicates that these methods are less reliable in narrow, turbid rivers, where increased surface clutter, limited image footprint, bank proximity, and rapid hydrodynamic transport lead to higher false-positive rates and more frequent missed detections [5],[8][9]. This discrepancy is consistent with the distinct hydrodynamic regime illustrated in Figure 3 and quantified through the parameter ranges reported in Table 1.

Al-Ruzouq et al. [22] reviewed sensing technologies and machine learning for oil spill monitoring and emphasized the value of combining multiple modalities. The present synthesis corroborates that conclusion but adds a river-specific perspective by showing that, in turbid freshwater systems, the combined use of in-situ sensors (chemical, optical, and water-level instruments) and AI-enhanced remote sensing is crucial for robust detection. Studies on intelligent water monitoring and IoT sensor networks [19],[21],[33][34],[54] demonstrate that AI-enabled infrastructures can provide continuous anomaly detection and rapid alerts. Building on this literature, the present work extends the analysis by jointly considering performance, latency, and cost (Table 2, Table 4, and Table 5) and by highlighting the roles of edge computing and federated learning as key enablers of real-time operation and privacy-preserving model adaptation in riverine applications [25],[28],[35].

With respect to AI model performance, environmental remote sensing studies report that advanced convolutional architectures and transformer-based models can reach accuracies up to approximately 96-98 % on benchmark datasets [17],[48],[53]. The ranges collated in Table 4 are consistent with these figures but emphasize that, under realistic edge-computing constraints, lightweight convolutional networks and YOLO-based detectors such as ResNet-50 and YOLOv8-nano are more suitable for deployment along rivers. These models typically maintain accuracies in the range of 94-96 % while achieving markedly lower latency and energy demand than larger transformer-based counterparts [42],[45]. This resource-constrained perspective, which explicitly links model choice to edge deployment feasibility, has received comparatively limited attention in earlier general reviews.

Comparative technology matrices that classify monitoring approaches by qualitative performance dimensions have appeared in broader environmental sensing surveys [63],[16], but these efforts rarely focus on riverine oil spills. The present review organizes technologies along four axes: detection accuracy, decision latency, cost, and environmental adaptability explicitly within the context of river hydrodynamics and turbidity (Table 5). This framing clarifies why hybrid AI-IoT strategies, integrating multiple sensing modalities with adaptive, edge-enabled analytics, are the most promising approach for achieving near-real-time detection in dynamic rivers. The conclusion is consistent with previous high-level overviews [7],[13],[22], while providing a more targeted, river-focused assessment that links hydrodynamic complexity, sensing architecture, and computational design choices within a unified comparative framework.

- Implication and Explanation of Findings

The integrated findings have several implications for both research and operational practice. A first implication concerns the hydrodynamic complexity of rivers, as illustrated in Figure 3 and Table 1. Tools developed for offshore conditions tend to underperform inland because SAR algorithms that assume relatively homogeneous sea states encounter substantial backscatter variability from banks, submerged structures, vegetation, and sediment plumes [8],[9], while optical methods struggle when oil is submerged as oil particle aggregates (OPA) or partially obscured by turbidity and vegetation [4],[7],[11]. The wide parameter ranges in Table 1 indicate that such misclassification is a predictable outcome of unmodelled heterogeneity rather than an exception. This points to the need for context-aware detection schemes that explicitly incorporate hydrological variables (flow rate, turbidity, sediment concentration) into models or thresholding strategies, rather than relying solely on image texture and tone.

A second implication arises from the performance patterns in Table 2 and Table 5, which show that no single technology is sufficient under all river conditions. Traditional methods remain essential as sources of ground truth for calibration and validation, but cannot provide the temporal resolution required for early warning. High-end remote sensing, including hyperspectral and UAV-based systems, offers detailed spatial and spectral information but is too costly for continuous deployment. AI-IoT networks close this gap by enabling local, high-frequency monitoring. Taken together, these results support a layered architecture in which wide-area satellite or UAV surveillance provides broad coverage. At the same time, dense networks of low-cost IoT nodes are placed at hydrodynamically critical locations identified by models similar to those in Figure 3. Such layering balances cost and coverage while exploiting the complementary strengths of each modality.

A third implication concerns resource constraints. The trade-offs documented in Table 4 and Figure 5 indicate that edge-oriented system design must give at least as much weight to latency and energy as to peak accuracy. In river reaches with limited power and connectivity, low-power devices running lightweight models such as MobileNet-V3 or YOLOv8-nano are often preferable, even when nominal accuracies are a few percentage points below those of transformer-based architectures. System-level performance, as reflected qualitatively in Table 5, can be higher because compact models can be deployed more densely and operated continuously, achieving redundancy and spatial coverage. The latency decomposition in (7) further shows that reducing the network component  via edge computing, can be more decisive for real-time response than marginal accuracy gains from centralized, computationally intensive models.

via edge computing, can be more decisive for real-time response than marginal accuracy gains from centralized, computationally intensive models.

A fourth implication is that data remains the main bottleneck. The accuracy range for AI models (approximately 90-98 %) depends strongly on dataset size, diversity, and reality. High accuracies often stem from clean, well-labelled datasets that do not fully represent the variability of operational rivers, whereas studies using field data from turbid or structurally complex reaches typically report lower and more variable performance [13],[43]. This discrepancy underscores the need for standardized, openly available riverine oil-spill datasets and harmonized evaluation protocols. Without such resources, cross-study comparisons will remain approximate, and models may fail when exposed to unseen conditions.

The final implication concerns operational integration. The analysis indicates that the main barrier to large-scale adoption is not only technical performance but also the degree of integration with hydrological networks, emergency-response procedures, and regulatory frameworks. High-performing AI-IoT systems will only be effective if responsible authorities trust the alerts, understand associated uncertainty, and have clear verification and response protocols. Future work should therefore address not only sensing and algorithms but also how monitoring systems are embedded in decision-making processes, data-governance arrangements, and cross-agency coordination, so that technical advances translate into tangible improvements in spill response and environmental protection.

- Strengths and Limitations

Several strengths of the present review can be identified. First, a structured narrative approach with elements of a scoping review was adopted, synthesizing 47 eligible articles selected through a transparent PRISMA-style identification, screening, and inclusion process (Figure 2). This procedure supports a balanced appraisal of heterogeneous technologies, traditional monitoring methods, satellite- and UAV-based remote sensing, IoT sensor networks, and AI-based algorithms rather than privileging a single modality. Second, the analysis is explicitly river-focused, systematically interpreting reported results through the lens of riverine hydrodynamics and turbidity, which remain underrepresented in a predominantly marine-oriented literature. Third, the organization of results into comparative tables (Table 2, Table 4, and Table 5), and their explicit linkage to hydrodynamic context (Figure 3, Table 1) and computational considerations (Figure 5, Equations (7) to Equation (8)), provides an integrated performance matrix spanning accuracy, latency, cost, and adaptability. Finally, the review deliberately distinguishes between literature-derived findings in Section 3 and the conceptual adaptive AI-IoT framework presented in Section 4, thereby addressing the concern of conflating empirical evidence with design preferences.

Several limitations should also be acknowledged. The compiled accuracy and latency ranges are descriptive rather than meta-analytic. The underlying studies employ different performance metrics (including accuracy, F1-score, mean average precision, and Intersection-over-Union), thresholds, class definitions, and test protocols, which precluded computation of pooled effect sizes and formal sensitivity analyses. Instead, ranges are reported, and outliers are handled qualitatively, introducing an element of interpretive judgement. The empirical evidence base for riverine environments remains relatively small and uneven: many of the highest reported AI performances originate from marine or laboratory-scale experiments, and their transferability to dynamic, turbid rivers is often argued qualitatively rather than demonstrated through dedicated validation campaigns. Moreover, several advanced techniques highlighted in this review, such as federated learning and GAN-based augmentation, are at an early stage of application in environmental monitoring and have frequently been evaluated on synthetic, limited, or non-public datasets; their robustness under large-scale, real-world deployment has not yet been established. The scope of the review is further constrained by the 2020-2025 publication window and by the databases and search strings employed, so that relevant grey literature, proprietary reports, and unpublished field trials may not be fully captured.

In summary, the review provides an integrated assessment of current riverine oil spill detection technologies, including their comparative strengths, limitations, and systemic implications. The assembled evidence indicates that hybrid AI-IoT and edge-enabled architectures constitute the most promising direction for achieving accurate, low-latency, and adaptable detection in hydrodynamically complex rivers. On this basis, Section 4 introduces an adaptive AI-IoT framework as a hydrodynamics-aware conceptual design that operationalizes the patterns and gaps identified in Section 3, while remaining analytically distinct from the empirical results synthesized in the preceding subsections.

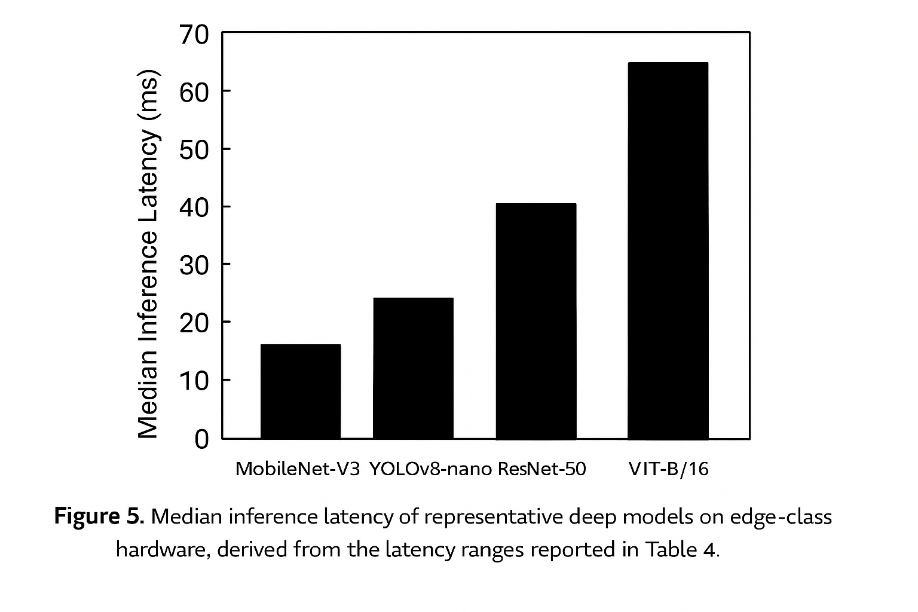

- Proposed Framework for Future Trends

To overcome recurring constraints in existing riverine oil spill detection systems, this research presents an adaptive, cost-effective, and energy-efficient AI-IoT framework for real-time environmental monitoring. The architecture mixes artificial intelligence (AI), Internet of Things (IoT) sensor networks, edge computing, and hydrodynamic modelling to enable precise, low-latency detection in dynamic freshwater environments. The proposed system, as shown in Figure 6, comprises a distributed network of solar-powered IoT sensor nodes strategically positioned at key sites, such as bridges, riverbanks, and anchored buoys. Each node regularly monitors important ecological parameters, including turbidity, temperature, hydrocarbon content, and flow velocity, using ultrasonic sensors, optical, and chemical sensors. These nodes are supported by lightweight AI modules that perform on-site anomaly detection, reducing the need for high-bandwidth cloud transmission and minimizing reaction time.

To enhance communication efficiency, sensor nodes are coupled by low-power wide-area networks (LPWANs) such as NB-IoT and LoraWAN, which provide reliable long-range data exchange with minimal energy utilization. Local edge gateways combine data from adjacent nodes and make more complicated inferences using models such as MobileNet or EfficientNet, which offer a balanced trade-off between accuracy and computing cost. The processed outputs are then communicated to a cloud platform for long-term storage, hydrodynamic modelling, and predictive analytics, enabling early warning and visualization of oil dispersion patterns at the regional scale. A web-based dashboard provides a centralized interface for environmental authorities, providing live sensor data, geographical warnings, and historical trends. Integration with emergency response systems ensures that identified spills automatically trigger notifications and containment recommendations. The design offers flexible scaling, and additional sensors or edge nodes can be integrated without affecting the system architecture.

By adding edge intelligence, renewable power sources, and federated learning for decentralized model updates, the architecture drastically decreases operational costs while retaining data security and adaptability. This integration of AI, IoT, and hydrodynamic modelling establishes a sustainable framework for continuous environmental surveillance, especially adapted to the unique challenges of narrow, turbulent, and sediment-rich riverine environments. The ensuing part examines the implementation considerations required to adapt this suggested framework into real-world deployments, addressing concerns such as sensor durability, connectivity optimization, interoperability, and large-scale scalability.

Figure 6. Adaptive AI-IOT Framework for Riverine Oil Spill Detection

- Implementation Considerations in Riverine Environments

The Effective deployment of the proposed adaptive AI-IoT framework in riverine environments requires addressing significant practical aspects that assure operational reliability, data integrity, and long-term sustainability. While the conceptual design exhibits tremendous potential for real-time oil spill detection, its effectiveness in field applications hinges on optimizing the implementation technique.

First, sensor deployment and maintenance must account for the demanding conditions in aquatic environments, including changing flow rates, sedimentation, and biological fouling. IoT sensor nodes should consequently adopt ruggedized enclosures, anti-corrosion materials, and biofouling-resistant coatings, supported by remote calibration and diagnostics to avoid human maintenance. Power autonomy can be extended through solar energy collection and low-power hardware setups.

Second, network stability is a significant barrier in remote or infrastructure-limited places. To counter frequent connectivity disruptions, the architecture combines edge computing for local data processing and temporary storage, enabling continued monitoring even when cloud access is unavailable. For data transmission, low-power wide-area networks (LPWAN) such as NB-IoT and LoRaWAN [20],[34] allow consistent, long-range communication with minimal energy usage.

Third, system interoperability and scalability are needed for real-world adoption. The modular structure of the proposed framework permits connection with existing national hydrological and environmental monitoring systems. Data communication through standardized APIs and MQTT protocols enables compatibility with emergency response platforms, enabling rapid coordination among ecological authorities.

Finally, the scalability and cost-effectiveness of implementation rely on the utilization of off-the-shelf components, open-source software, and lightweight AI models suited for embedded edge devices. Together, these considerations ensure that the framework remains practical, durable, and economically viable for large-scale riverine oil spill surveillance, especially in resource-constrained settings.

- CONCLUSIONS

This review examined riverine oil spill detection from a hydrodynamics-aware and technology-agnostic perspective, synthesizing 47 studies published between 2020 and 2025. The rivers constitute a fundamentally different detection environment from the open sea: strongly varying flow, turbidity, and sediment regimes create spatially and temporally heterogeneous backscatter and radiometric signatures, as evidenced by the data collected. Under these conditions, methods that perform well in marine or laboratory settings, particularly SAR, satellite images, and deep learning-based classifiers, often exhibit degraded performance in narrow, turbid channels, leading to elevated false-positive and missed-detection rates. In contrast, the comparative analysis reveals that hybrid AI-IoT architectures, supported by edge computing and adaptive updates, better align with the combined requirements of accuracy, latency, and environmental adaptability in dynamic riverine environments.

According to the above, several contributions emerge from this synthesis. First, developed a river-focused perspective that explicitly links detection performance to physical drivers through hydrodynamic parameters (Figure 3, Table 1) and their impact on sensing performance (Table 2, Table 4, and Table 5). Second, constructed a comparative performance matrix that positions traditional monitoring, remote sensing, IoT sensor networks, and AI-based models along four axes: detection accuracy, decision latency, cost, and environmental adaptability, clarifying the operational niches in which each approach is most appropriate. Third, articulated a conceptual adaptive AI-IoT framework in the main body of the paper as a hydrodynamics-aware design that integrates multi-sensor fusion, edge and federated learning, and iterative model refinement, thereby formalizing how disparate findings from the literature can be combined into a coherent design logic for riverine monitoring systems. Fourth, the analysis frames riverine oil spill detection as a socio-technical challenge, highlighting that sensing and computation must be aligned with institutional workflows, regulatory constraints, and response capabilities.

The conclusions drawn from this review should be interpreted in light of several methodological limitations and sources of uncertainty. The performance ranges reported for different technologies are descriptive rather than meta-analytic because the underlying studies employ heterogeneous metrics (accuracy, F1-score, mean average precision, Intersection-over-Union), thresholds, class definitions, and test protocols. Pooled effect sizes and formal sensitivity analyses were therefore not feasible, and the ranges in Table 4 and Table 5 are best viewed as indicative envelopes rather than precise benchmarks. In addition, the empirical evidence base focused specifically on riverine conditions remains limited and uneven: many of the highest reported accuracies originate from marine, laboratory, or synthetic datasets, and their transferability to fully dynamic, cluttered rivers is often argued qualitatively rather than demonstrated through systematic field validation. Advanced techniques highlighted in this review, such as federated learning and GAN-based augmentation, have so far been applied only in early-stage or small-scale settings, and their robustness in large, operational river networks has yet to be established. Finally, the review is confined to a 2020-2025 publication window and to the selected databases and search strings; therefore, relevant grey literature and unpublished field deployments may not be fully represented.

Within these constraints, the overall conclusion is that hybrid AI-IoT and edge-enabled architectures, designed with explicit attention to river hydrodynamics, data limitations, and resource constraints, offer the most credible pathway toward accurate, low-latency, and adaptable oil spill detection in riverine environments, while also providing a structured basis for future experimental validation and system deployment.

- FUTURE WORK

Future work should first address the limited and uneven empirical base for riverine oil spill detection. This involves developing standardized, openly accessible river datasets that include multi-season imagery, in situ sensor streams, and agreed evaluation protocols. With these, accuracy, latency, and robustness can be compared fairly across methods. Once such benchmarks are established, multi-site field trials of the proposed hydrodynamics-aware AI-IoT architectures are needed. These should occur in rivers with contrasting flow regimes, turbidity, infrastructure, and pollution profiles. Systematic reporting should cover false alarms, missed detections, end-to-end response times, and life-cycle cost. To overcome resource and connectivity constraints, future research should also explore resource-aware model design and deployment strategies. These should jointly optimize architecture size, FLOPs, communication patterns, and on-node learning schemes such as federated and continual learning under realistic energy and bandwidth budgets. In parallel, there is a need to advance GAN-based augmentation and other data-synthesis techniques. These should move from small-scale experiments toward rigorously evaluated pipelines that demonstrably improve generalisation in cluttered, dynamic rivers. Finally, deeper integration of AI-IoT sensing with hydrological and transport models, regulatory frameworks, and civil protection workflows is essential. This includes work on data governance, alert validation, human AI interaction, and institutional trust. Such efforts ensure that technically promising systems can translate into operational tools for riverine environmental protection and emergency response.

REFERENCES

- M. Riazi, "Sources and Causes of Oil Spills," in Oil Spill Occurrence, Simulation, and Behavior, pp. 47-80, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429432156-3.

- D. Kvoˇcka, D. Žagar, and P. Banovec, "A Review of River Oil Spill Modeling," Water, vol. 13, no. 12, p. 1620, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/w13121620.

- J. Wang, Y. Zhou, L. Zhuang, L. Shi, and S. Zhang, “Study on the critical factors and hot spots of crude oil tanker accidents,” Ocean & Coastal Management, vol. 217, p. 106010, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.106010.

- A. Jiang, L. Han, C. Wang, and J. Zhao, "Migration movements of accidentally spilled oil in environmental waters: a review," Water, vol. 15, no. 23, p. 4092, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/w15234092.

- C. Kang, H. Yang, G. Yu, J. Deng, and Y. Shu, "Simulation of Oil Spills in Inland Rivers," Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, vol. 11, no. 7, p. 1294, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse11071294.

- X. Wen, A. Fan, J. Wang, Y. Xia, S. Chen, and Y. Yang, "Different Emergency Response Strategies to Oil Spills in Rivers Lead to Divergent Contamination Compositions and Microbial Community Response Characteristics," Microorganisms, vol. 13, no. 6, p. 1193, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13061193.

- P. Keramea, K. Spanoudaki, G. Zodiatis, G. Gikas, and G. Sylaios, "Oil spill modeling: A critical review on current trends, perspectives, and challenges," Journal of marine science and engineering, vol. 9, no. 2, p. 181, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse9020181.

- M. Zakzouk, A. M. Abdulaziz, I. Abou El-Magd, A. S. Dahab, and E. M. Ali, "Automated oil spill detection using deep learning and SAR satellite data for the northern entrance of the Suez Canal," Scientific Reports, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 20107, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03028-1.

- X. Li et al., "Deep-learning-based information mining from ocean remote-sensing imagery," National Science Review, vol. 7, no. 10, pp. 1584-1605, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwaa098.

- T. De Kerf, J. Gladines, S. Sels, and S. Vanlanduit, "Oil spill detection using machine learning and infrared images," Remote sensing, vol. 12, no. 24, p. 4090, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12244090.

- J. Yang, J. Wang, Y. Hu, Y. Ma, Z. Li, and J. Zhang, "Hyperspectral marine oil spill monitoring using a dual-branch spatial–spectral fusion model," Remote Sensing, vol. 15, no. 17, p. 4170, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15174170.

- J. Yang, Y. Hu, J. Zhang, Y. Ma, Z. Li, and Z. Jiang, "Identification of marine oil spill pollution using hyperspectral combined with thermal infrared remote sensing," Frontiers in Marine Science, vol. 10, p. 1135356, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2023.1135356.

- S. Temitope Yekeen and A.-L. Balogun, "Advances in remote sensing technology, machine learning and deep learning for marine oil spill detection, prediction and vulnerability assessment," Remote Sensing, vol. 12, no. 20, p. 3416, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12203416.

- Y. Li, Q. Yu, M. Xie, Z. Zhang, Z. Ma, and K. Cao, "Identifying oil spill types based on remotely sensed reflectance spectra and multiple machine learning algorithms," IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, vol. 14, pp. 9071-9078, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2021.3109951.

- J. Kang, C. Yang, J. Yi, and Y. Lee, "Detection of Marine Oil Spill from PlanetScope Images Using CNN and Transformer Models," Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, vol. 12, no. 11, p. 2095, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse12112095.

- M. S. Binetti, C. Massarelli, and V. F. Uricchio, "Machine learning in geosciences: A review of complex environmental monitoring applications," Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 1263-1280, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/make6020059.

- D. Wang et al., "BO-DRNet: An improved deep learning model for oil spill detection by polarimetric features from SAR images," Remote Sensing, vol. 14, no. 2, p. 264, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14020264.

- Y. Zhang et al., "A novel YOLOv11-driven deep learning algorithm for UAV multispectral oil spill detection in inland lakes," Journal of King Saud University Computer and Information Sciences, vol. 37, no. 5, p. 108, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1007/s44443-025-00117-z.

- G. A. Pradana and S. L. Siregar, "Development of An Internet of Things Based Oil Spill Incident Early Warning System," in BIO Web of Conferences, vol. 92, p. 01011, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1051/bioconf/20249201011.

- A. Alzahrani, P. Kostkova, H. Alshammari, S. Habibullah, and A. Alzahrani, "Intelligent integration of AI and IoT for advancing ecological health, medical services, and community prosperity," Alexandria Engineering Journal, vol. 127, pp. 522-540, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2023.12.032.

- J. Roostaei, Y. Z. Wager, W. Shi, T. Dittrich, C. Miller, and K. Gopalakrishnan, "IoT-based edge computing (IoTEC) for improved environmental monitoring," Sustainable computing: informatics and systems, vol. 38, p. 100870, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suscom.2023.100870.

- R. Al-Ruzouq et al., "Sensors, features, and machine learning for oil spill detection and monitoring: A review," Remote Sensing, vol. 12, no. 20, p. 3338, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12203338.

- S. Asadzadeh, W. J. de Oliveira, and C. R. de Souza Filho, "UAV-based remote sensing for the petroleum industry and environmental monitoring: State-of-the-art and perspectives," Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, vol. 208, p. 109633, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2021.109633.

- P. Jiang, S. Tong, Y. Wang, and G. Xu, "Modelling the oil spill transport in inland waterways based on experimental study," Environmental Pollution, vol. 284, p. 117473, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117473.

- X. Zhang et al., “Fedyolo: Augmenting federated learning with pretrained transformers,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.04905, 2023, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2307.04905.

- M. H. Obaid and A. H. Hamad, "Deep Learning Approach for Oil Pipeline Leakage Detection Using Image-Based Edge Detection Techniques," Journal Européen des Systèmes Automatisés, vol. 56, no. 4, 2023, https://doi.org/10.18280/jesa.560416.

- A. El-Hoshoudy, "Application of Artificial Intelligence and Federated Learning in Petroleum Processing," in Artificial Intelligence Using Federated Learning, pp. 134-155, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003482000-8.

- T. Miller, I. Durlik, E. Kostecka, and A. Puszkarek, "Federated Learning for Environmental Monitoring: A Review of Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions," Applied Sciences, vol. 15, no. 23, p. 12685, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312685.

- O. Eldirdiry et al., "Using AI-Enhanced UAVs to Detect and Size Marine Contaminations," 2024 2nd International Conference on Unmanned Vehicle Systems-Oman (UVS), pp. 1-6, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/UVS59630.2024.10467155.

- T. I. Umaha et al., "SpillNet: A modified convolutional neural network model for oil spill detection," Asian Journal of Water, Environment and Pollution, p. 8282, 2025, https://doi.org/10.36922/ajwep.8282.

- C. Zhan, K. Bai, B. Tu, and W. Zhang, "Offshore oil spill detection based on CNN, DBSCAN, and hyperspectral imaging," Sensors, vol. 24, no. 2, p. 411, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/s24020411.

- S. Dehghani-Dehcheshmeh, M. Akhoondzadeh, and S. Homayouni, "Oil spills detection from SAR Earth observations based on a hybrid CNN transformer network," Marine Pollution Bulletin, vol. 190, p. 114834, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2023.114834.

- Chansi, K. Hadwani, and T. Basu, "Artificial intelligence-, machine learning-and Internet of Things-based sensors for detection of marine pollutants," in Sensors for Marine Biosciences: Next-generation sensing approaches, pp. 6-1-6-33, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1088/978-0-7503-5999-3ch6.

- S. Bello, M. D. Amadi, and A. H. Rawayau, "Internet of Things-Based Wireless Sensor Network System for Early Detection and Prevention of Vandalism/Leakage on Pipeline Installations in The Oil and Gas Industry in Nigeria," Fudma journal of sciences, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 240-246, 2023, https://doi.org/10.33003/fjs-2023-0705-1927.

- N. Victor et al., "Federated learning for IoUT: Concepts, applications, challenges and opportunities," arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.13976,2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/IOTM.001.2200067.

- S. M. Popescu et al., "Artificial intelligence and IoT driven technologies for environmental pollution monitoring and management," Frontiers in Environmental Science, vol. 12, p. 1336088, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2024.1336088.

- F. Zhang et al., "Recent methodological advances in federated learning for healthcare," Patterns, vol. 5, no. 6, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2024.101006.

- A. A. Ali, G. H. Abdul-Majeed, and A. Al-Sarkhi, "Review of multiphase flow models in the petroleum engineering: Classifications, simulator types, and applications," Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering, vol. 50, no. 7, pp. 4413-4456, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-024-09302-0.

- M. Nickzamir and S. M. S. A. Gandab, "A Hybrid Random Forest and CNN Framework for Tile-Wise Oil-Water Classification in Hyperspectral Images," arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.00232, 2025, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2502.00232.

- Chansi, K. Hadwani, and T. Basu, "Artificial intelligence, machine learning and Internet of Things-based sensors for detection of marine pollutants," in Sensors for Marine Biosciences: Next-generation sensing approaches, pp. 6-1-6-33, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1088/978-0-7503-5999-3ch6.

- R. E. Kalman, "A new approach to linear filtering and prediction problems," Journal of fluids Engineering, vol. 82, no. 1, pp. 35-45,1960, https://doi.org/10.1115/1.3662552.

- C. M. Bishop, "Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning," The American Statistical Association, vol. 103, no. 482, pp. 886-887, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1198/jasa.2008.s236.

- M. Sivapriya and S. Suresh, "ViT-DexiNet: a vision transformer-based edge detection operator for small object detection in SAR images," International Journal of Remote Sensing, vol. 44, no. 22, pp. 7057-7084, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1080/01431161.2023.2277167.

- G. Zhou, J. Yu, and S. Zhou, "LSCB: a lightweight feature extraction block for SAR automatic target recognition and detection," International Journal of Remote Sensing, vol. 44, no. 8, pp. 2548-2572, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1080/01431161.2023.2203342.

- J. W. Shim, “Enhancing cross entropy with a linearly adaptive loss function for optimized classification performance,” Scientific Reports, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 27405, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78858-6.

- S. Song, K. Chaudhuri, and A. D. Sarwate, "Stochastic gradient descent with differentially private updates," in 2013 IEEE global conference on signal and information processing, pp. 245-248, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1109/GlobalSIP.2013.6736861.

- J. Fan and C. Liu, "Multitask gans for oil spill classification and semantic segmentation based on sar images," IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, vol. 16, pp. 2532-2546, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2023.3249680.

- N. A. Bui, Y. Oh, and I. Lee, "Oil spill detection and classification through deep learning and tailored data augmentation," International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, vol. 129, p. 103845, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2023.103845.

- I. Goodfellow et al., “Generative adversarial networks,” Communications of the ACM, vol. 63, no. 11, pp. 139-144, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1145/3422622.

- Z. Chen et al., "An empirical study of latency in an emerging class of edge computing applications for wearable cognitive assistance," in Proceedings of the Second ACM/IEEE Symposium on Edge Computing, pp. 1-14, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1145/3132211.3134458.

- V. Gopinath, S. Sachin Kumar, N. Mohan, and K. Soman, "Oil Spill Detection from Images Using Deep Learning," in International Conference on Advances in Data Science and Computing Technologies, pp. 631-639, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-3656-4_65.

- C. Wang and A. Coulson, "Fine Tuning MobileNet Neural Networks for Oil Spill Detection," I-GUIDE 2023, https://doi.org/10.5703/1288284317671.

- M. Khirwar and A. Narang, "GeoViT: versatile vision transformer architecture for geospatial image analysis," 2024 International Conference on Machine Intelligence for GeoAnalytics and Remote Sensing (MIGARS), pp. 1-3, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/MIGARS61408.2024.10544759.

- M. Dalal, P. Mittal, V. Goyal, R. Updahyay, and N. Sood, “Evaluation of deep learning models for oil tank detection utilizing SPOT imagery,” In Recent Trends in Intelligent Computing and Communication, pp. 794-799, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003593089-124.

- D. Liu et al., "Assessing Environmental Oil Spill Based on Fluorescence Images of Water Samples and Deep Learning," Journal of Environmental Informatics, vol. 42, no. 1, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3808/jei.202300491.

- R. Gong and J. Zhou, "Research on application of deep learning in lithology recognition of oil and gas reservoir," in 2021 IEEE International Conference on Power, Intelligent Computing and Systems (ICPICS), pp. 110-115, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICPICS52425.2021.9524171.