ISSN: 2685-9572 Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro

Vol. 8, No. 1, February 2026, pp. 141-150

Investigation of Manufacture Tolerances on Torque Pulsation Profile of Interior Permanent Magnet Motor with Third Harmonic Injected Sinusoidal Rotor Iron Pole

Ahlam Luaibi Shuraiji 1, Kassim Rasheed Hameed 2, Salam Waley Shneen 3

1 College of Electromechanical Engineering Department, University of Technology–Iraq, Baghdad, Iraq

2 Department of Electrical Engineering, College of Engineering /Al-Mustansiriya, University of Technology–Iraq, Baghdad, Iraq

3 Energy and Renewable Energies Technology Center, University of Technology–Iraq, Baghdad, Iraq

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 04 September 2025 Revised 03 December 2025 Accepted 29 January 2026 |

|

Torque ripple is a significant undesirable aspect of permanent magnet (PM) machine. It is mainly contributed by cogging torque, which is inherit feature of the PM machine. Interior permanent magnet (IPM) motor with a sinusoidal + third-order harmonic injected rotor pole shape has been introduced as one of the most efficient rotor pole arc iron shape techniques to minimize the cogging torque. Such method showed a reduction in the cogging torque compared to the traditional designs. Generally, imperfections in the manufacturing process can exacerbate cogging torque and, by extension, torque ripple. This research assesses how manufacturing tolerances influence the torque ripple of the IPM motor having sinusoidal + third order harmonic rotor pole shape. The investigation has been carried out using two-dimension finite element analysis(2D-FEA) method, ANSOFT MAXWELL program. Different models of the IPMs with sinusoidal + third order harmonic rotor pole shape have been made to simulate healthy, eccentricity and PM diversity cases. According to the simulation results, it has been found that PM diversity leads to introduce additional harmonics in the cogging torque waveforms, i.e., in addition to the fundamental harmonic, which is the 60th harmonic orders, the 12th harmonic and its multiples harmonic orders were presented, consequently resulting in increasing the torque ripple. Moreover, the obtained results have shown that the static eccentricity has more negative effect on the torque ripple compared to the dynamic counterpart, i.e. the torque ripple of the static eccentricity is about 20% higher than that of the dynamic counterpart. |

Keywords: Torque Pulsation; Cogging Torque; Interior Permanent Magnet Machine; Rotor Eccentricity; Permanent Magnet Diversity |

Corresponding Author: Salam Waley Shneen, Energy and Renewable Energies Technology Center, University of Technology –Iraq. Email: salam.w.shneen@uotechnology.edu.iq |

This work is open access under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: A. L. Shuraiji, K. R. Hameed, and S. W. Shneen, “Investigation of Manufacture Tolerances on Torque Pulsation Profile of Interior Permanent Magnet Motor with Third Harmonic Injected Sinusoidal Rotor Iron Pole,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 141-150, 2026, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v8i1.14647. |

- INTRODUCTION

The introduction of high-energy and high-temperature-resistant PM materials has led to the development of specific types of electrical machines known as permanent magnetic machines (PMMs), delivering enhanced performances in terms of torque density, efficiency, and robust structures compared to electrically excited machines [1]-[4]. Consequently, PMMs have gained significant attention over the last two decades [5][6]. PMMs are designed in various configurations and categorized based on the permanent magnets' placement on stationary or moving parts, resulting in stator PMMs and rotor PMMs. Among rotor PMMs, the types are further divided into Surface-mounted PMMs and Interior PMMs.

Interior PMMs, widely used in many sectors, are noted for their high efficiency, power density, and dynamic performance [7]-[10]. A significant challenge with PMMs is the no-load torque known as cogging torque, resulting from the interaction between the stator teeth and rotor PMs, causing speed ripple and vibrations, especially at low speeds [11]-[14]. Reducing cogging torque is crucial as it directly impacts the performance of PMMs, necessitating ongoing research and development in this area [15]-[18].

Techniques to reduce cogging torque are typically categorized into design and control methods. The design method focuses on modifications during the machine's design phase, while the control method involves adjustments during operation [19][20]. Rotor pole shaping is one of the most effective design techniques to mitigate cogging torque. Studies have utilized rotor pole shaping to reduce the cogging torque in IPMMs, discussing IPMMs with eccentric and sinusoidal rotor pole iron shapes [21].

IPMMs with segmented rotor pole iron have also been explored to enhance PM material utilization and reduce cogging torque. Comparisons with models such as the Camry 2007 motor showed that the proposed motor achieved a 50% reduction in torque ripple and a 15% increase per PM [22]. However, reducing cogging torque typically decreases the electromagnetic torque of the motor. To counteract this, an IPMM with a sinusoidal + third-order harmonic rotor iron pole shape was introduced to enhance the torque capability of shaped rotor iron pole IPMMs [23].

Manufacturing tolerances significantly affect cogging torque in mass-produced machines [24][25]. Recent studies have focused on the impact of manufacturing tolerance on the cogging torque of PM motors. The influence of stator structure on cogging torque due to rotor manufacturing tolerance was investigated, showing that modifying the teeth with partial dummy slots at the center of each tooth's inner periphery reduces the fundamental harmonic of cogging torque [27]. Imperfections in PMs due to mass production also affect cogging torque, introducing additional harmonics [28].

Further studies examined the effects of PM imperfection and tooth bulges on the performance of IPMMs with different stator-rotor combinations and IPMMs with eccentric and sinusoidal rotor iron poles. These studies noted that the most sensitive cases for each combination showed increased fundamental components of cogging torque due to PM diversity. However, the sinusoidal rotor shape machine exhibited less sensitivity to PM diversity than the eccentric counterparts [29][30]. All machines demonstrated the same sensitivity to tooth bulges, leading to additional cogging torque harmonics.

While the performance of machines with a sinusoidal + third-order harmonic rotor pole shape has been comprehensively investigated, the sensitivity of cogging torque to manufacturing tolerances has not been previously reported. Therefore, this paper examines the impact of two manufacturing tolerances—PM diversity and rotor eccentricity—on the performance of IPMMs with sinusoidal + third-order harmonic rotor shapes, focusing on cogging torque and torque ripple.

The analysis uses two-dimensional finite element analysis software ANSOFT MAXWELL, beginning with a description of the topology, followed by a discussion on the fundamentals of cogging torque, PM diversity, and rotor eccentricity. The performance under ideal and tolerance-affected conditions is compared, concluding with a synthesis of the findings

- TOPOLOGY DESCRIPTION

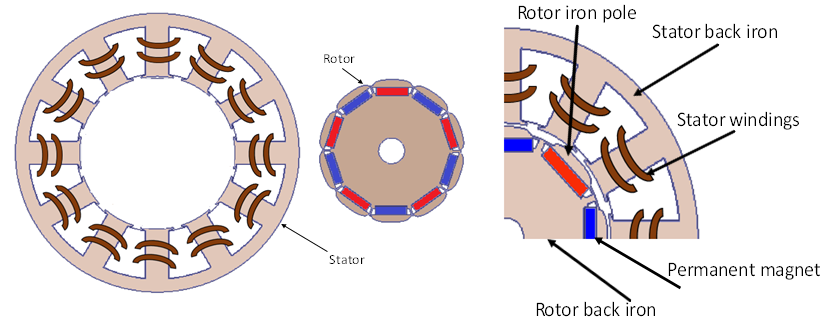

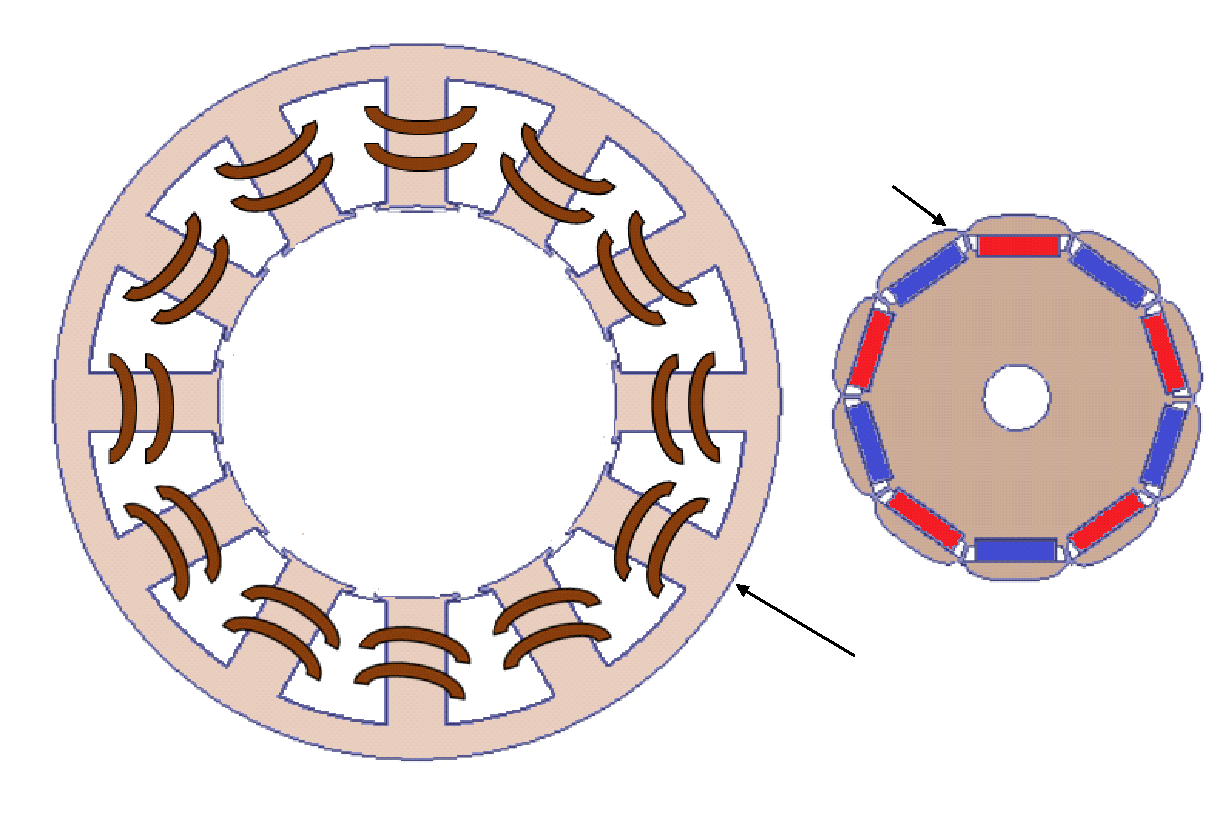

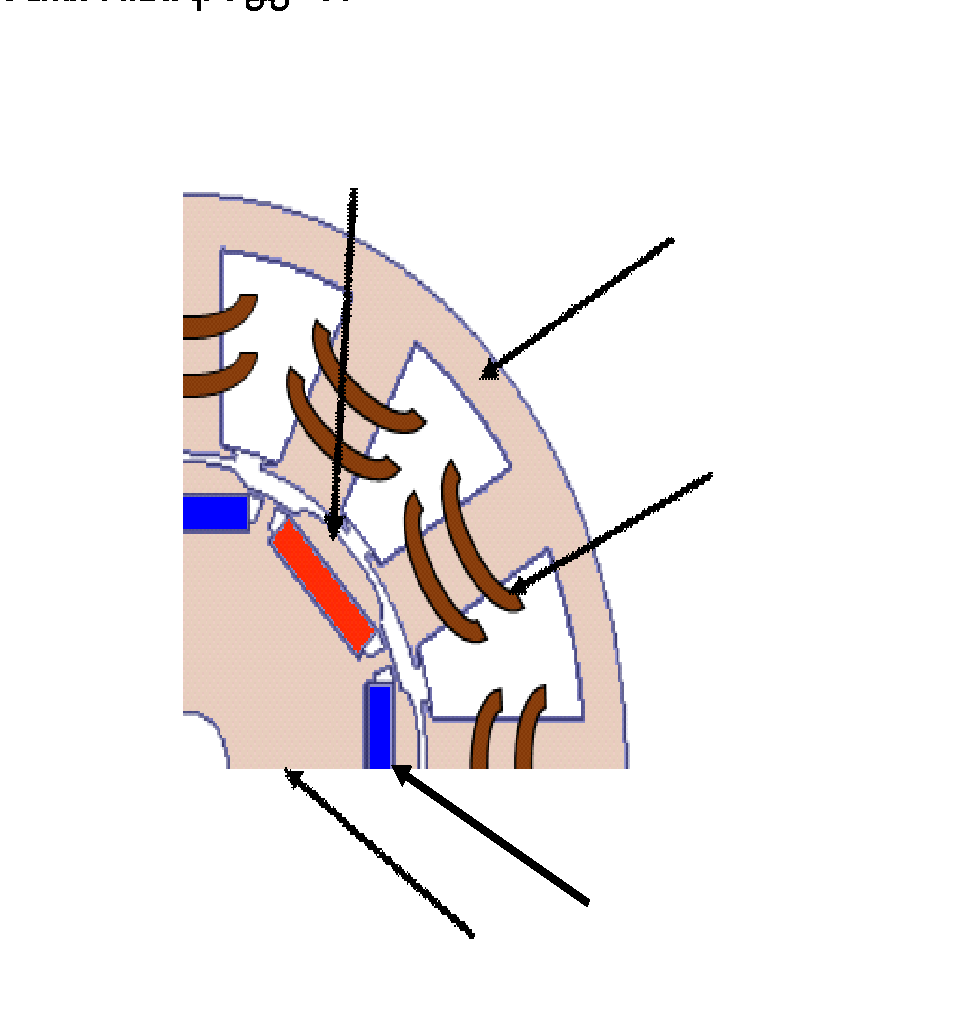

IPM motor with (12/10) stator/ rotor pole combination as illustrated in Figure 1. The rotor iron pole has been designed with sinusoidal + third ordered harmonic shape. At the same time, the stator has single-layer concentrated winding, which is preferable over other types since they have less copper usage, leading to efficiency improvement due to reduced copper losses.

|

|

(a) Stator and rotor | (b) Zoom in on the motor |

Figure 1. Motor configuration

- COGGING TORQUE

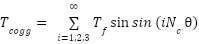

It is well known that all PM machines suffer from the cogging torque resulting from the interaction between iron and the permanent magnet. Such an inherent torque does not contribute to the desirable machine torque; however, it causes noise, vibration, and torque ripple. According to [31], cogging torque is a function of rotor position ( ) and the smallest common multiple between stator slot and rotor pole numbers (

) and the smallest common multiple between stator slot and rotor pole numbers ( ), and it can be expressed as:

), and it can be expressed as:

|

| (1) |

On the other hand, the cogging torque waveform's period and the main harmonic order are calculated by [31].

|

| (2) |

|

| (3) |

where  is cogging torque,

is cogging torque,  is the fundamental component of the cogging torque waveform, and CTP is the Cogging torque period.

is the fundamental component of the cogging torque waveform, and CTP is the Cogging torque period.

- MANUFACTURING TOLERANCES

The current study considers two manufacturing tolerance issues, PM diversity and rotor eccentricity.

- PM Diversity

According to the literature, diversities in the PM remanence properties of PM machines are caused by uneven magnetization and non-uniform PM materials. For the N45SH PM material used in this paper, the ideal relative magnetic flux density (Br) value is 1.32T. In contrast, the maximum value may be reached at 1.42 T. It should be noted that the PM diversity in this study was simulated by changing the value of the Br, i.e. the ideal and the maximum values of the Br have been considered average and up-average values, respectively.

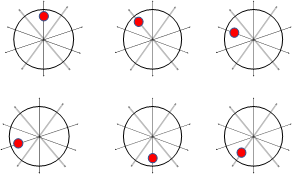

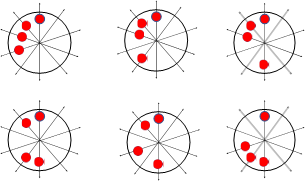

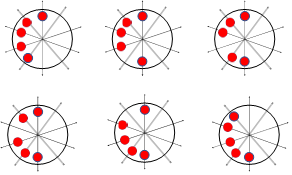

Considering the PM number in the understudying machine, the probabilities of PM diversities are ( ), meaning 1024 cases should be studied to cover all the possibilities. However, due to the merroir and symmetrical configuration of the machine, this can be reduced to about 512 cases [29], some of which are illustrated in Figure 2. The arrows with the circular represent the diversified PM. Due to the high number of cases that include PM diversities, one case from each possible property shown in Figure 2 will be considered in this study. Hence, five models will be designed to investigate this paper’s PM diversity.

), meaning 1024 cases should be studied to cover all the possibilities. However, due to the merroir and symmetrical configuration of the machine, this can be reduced to about 512 cases [29], some of which are illustrated in Figure 2. The arrows with the circular represent the diversified PM. Due to the high number of cases that include PM diversities, one case from each possible property shown in Figure 2 will be considered in this study. Hence, five models will be designed to investigate this paper’s PM diversity.

|

|

(a) one PM | (b) two PMs |

|

|

(c) three PMs | (d) four PMs |

|

(e) five PMs |

Figure 2. Some possible PM diversities: (a) one PM (single pole), (b) two PMs (two poles), (c) three PMs (three poles), (d) four PMs (four poles), (e) five PMs (five poles)

- Rotor Eccentricity

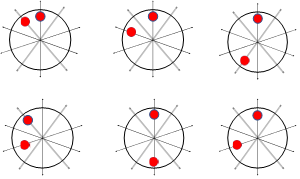

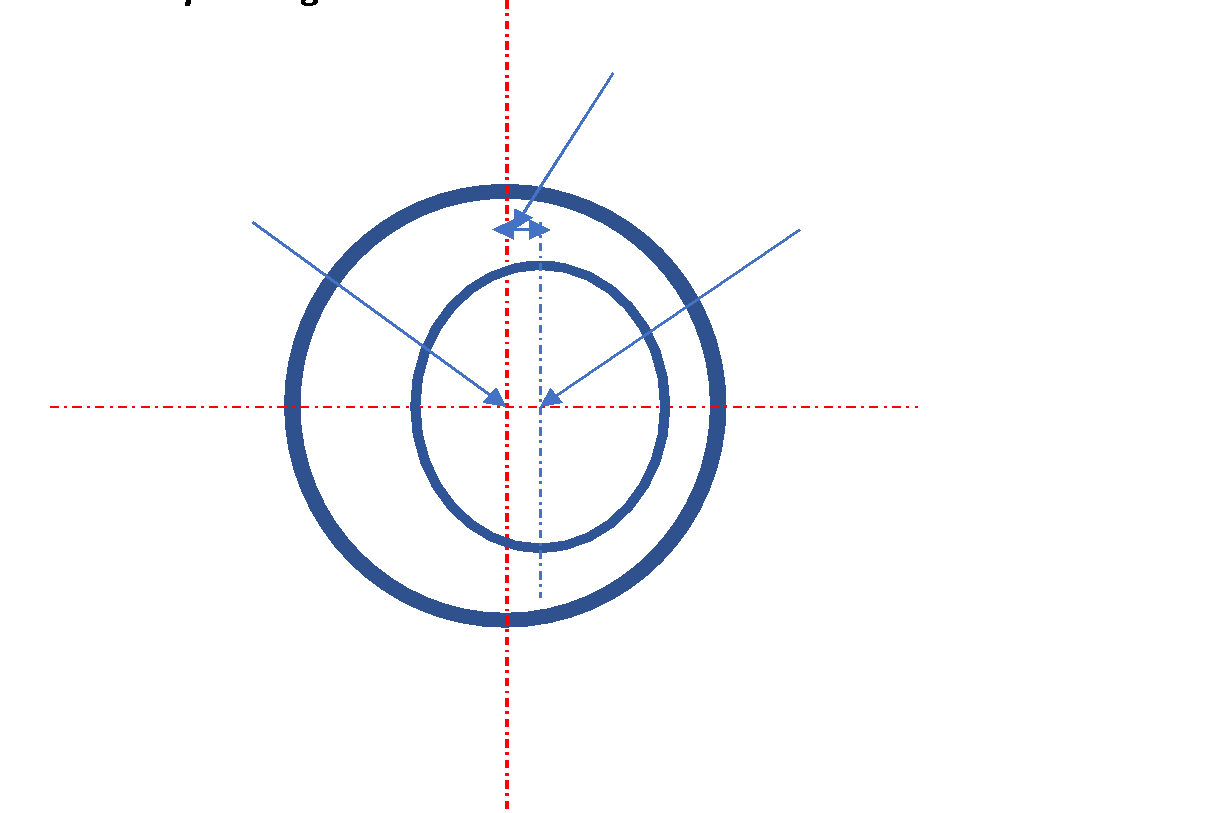

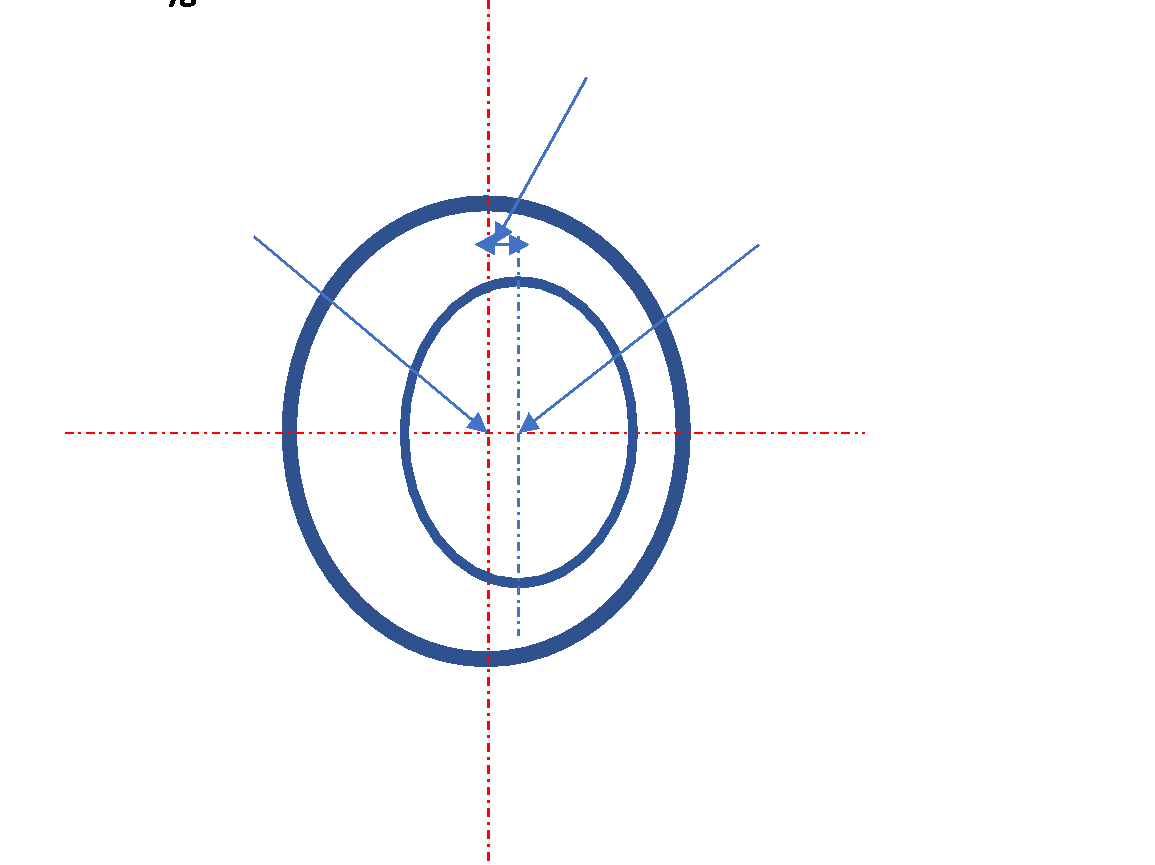

Usually, the electrical machine's rotor experiences two types of eccentricities, i.e., static and dynamic. In static eccentricity, the rotor center will be shifted from the stator center, which will rotate on its center, as shown in Figure 3(a). In contrast, on the dynamic cause, the rotor has its center and rotates on the stator center, i.e., the original center of the machine, as shown in Figure 3(b). Exciting the rotor eccentricity in the machine increases the torque ripple and unbalanced magnetic force, which reduces the electromagnetic torque and leads to vibrations and noise.

|

|

- static

| - dynamic

|

Figure 3. Rotor Eccentricities, (a) static, (b) dynamic

- METHODOLOGY

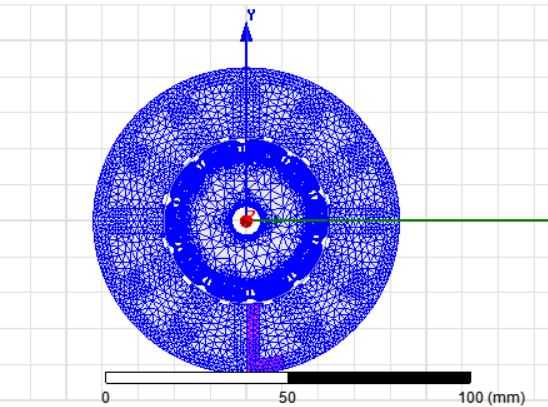

2D- ANSOFT MAXWELL program was used to create eight different models of the IPM motor with sinusoidal + third order harmonic rotor pole shape. The eight models have been built to simulate the healthy, eccentric (static and dynamic) and the PM diversity conditions, it should be mentioned that 5 models are designed to cover the first possible case of each PM diversities shown in Figure 2. The authors have adopted the same designed parameters of refences [23], in which designed of the IPM motor with sinusoidal + third harmonic order injected rotor pole iron was discussed.

The no-load operation case was used to obtained the results of the cogging torque for all models. While simulation results of the torque ripple were obtained under the full load operation condition. It must be noted that all the simulation results were carried out under the transient solution type. Moreover, the mech operations was length type, inside selection. In order to have an accurate result the designed motor was divided in to five regains when the mech operation was assigned. Which included stator, copper, PMs, rotor and the air-gap. As it can be noted in Figure 4 the most refine mech is for the air-gap regain, since the cogging torque results accuracy are highly depending on the air-gap mech. The maximum length of element for the air-gap regain was 0.1mm and the maximum number of elements were 1000.

Figure 4. Mech of different parts of the designed motor

- RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

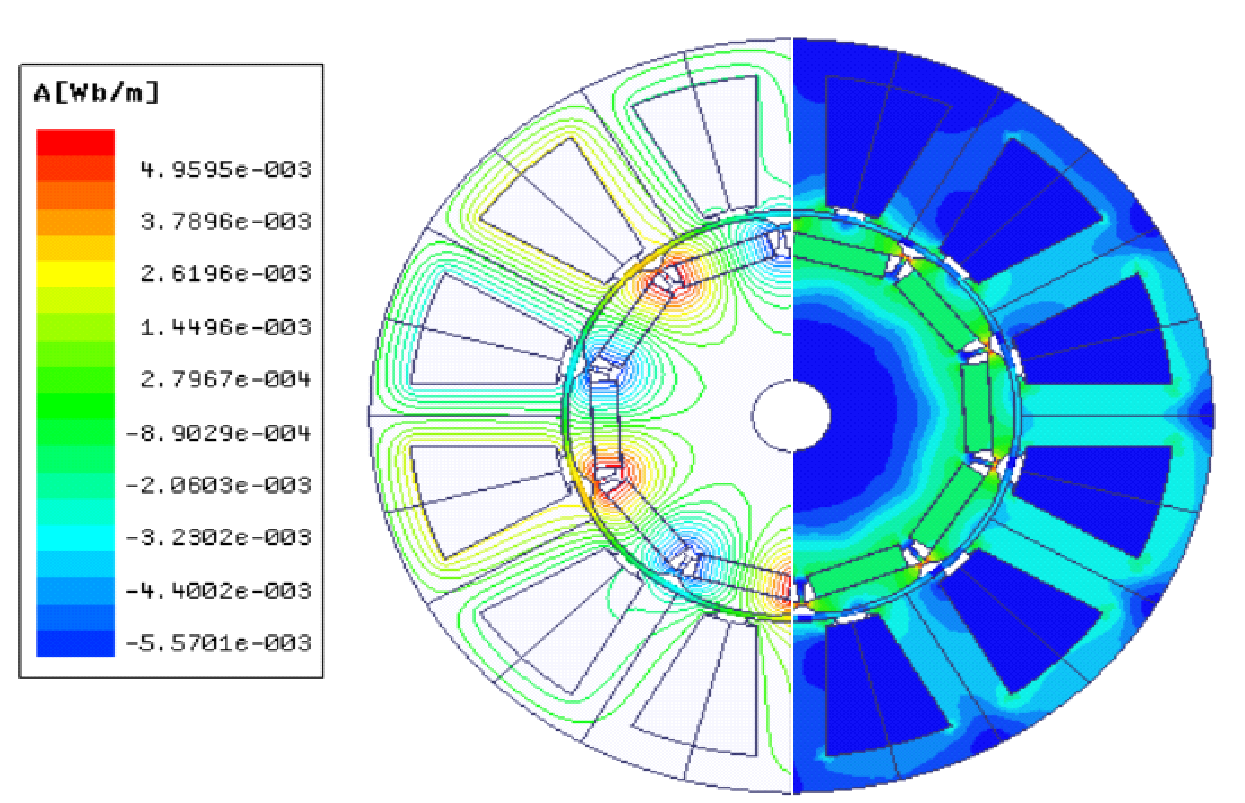

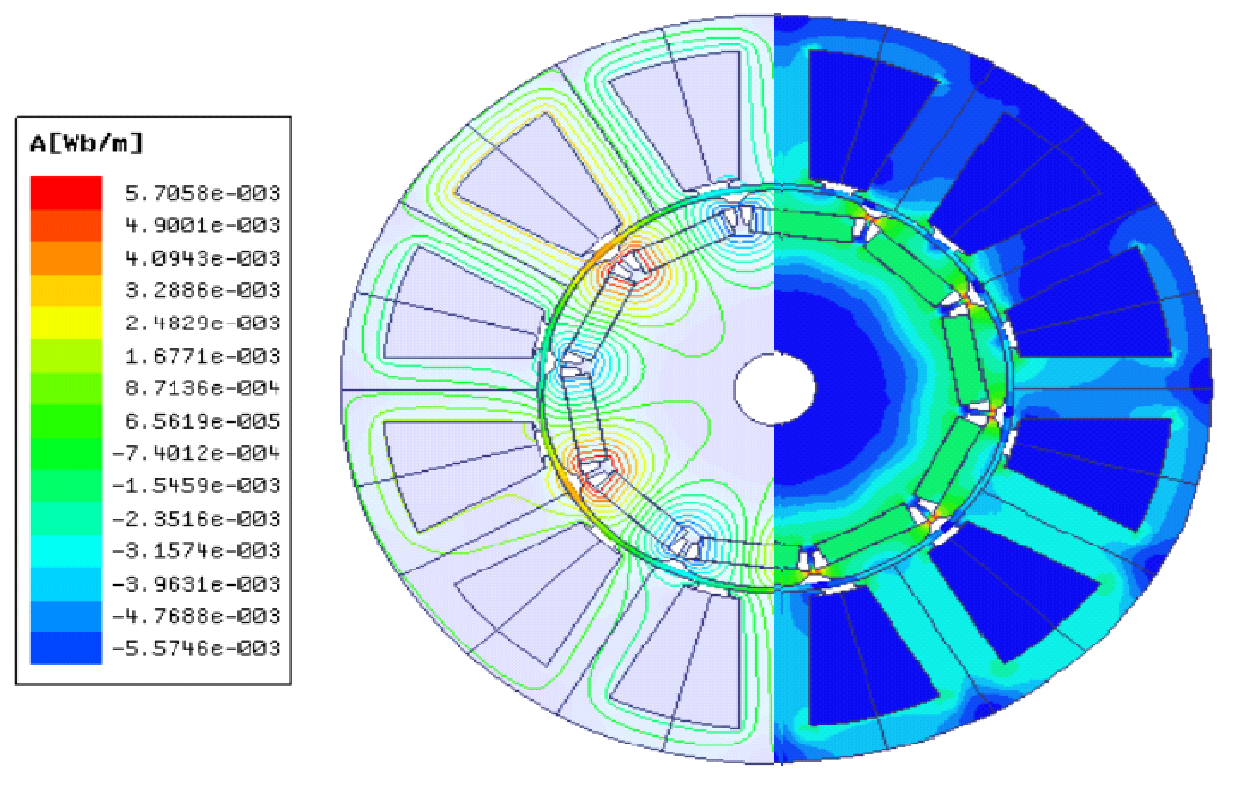

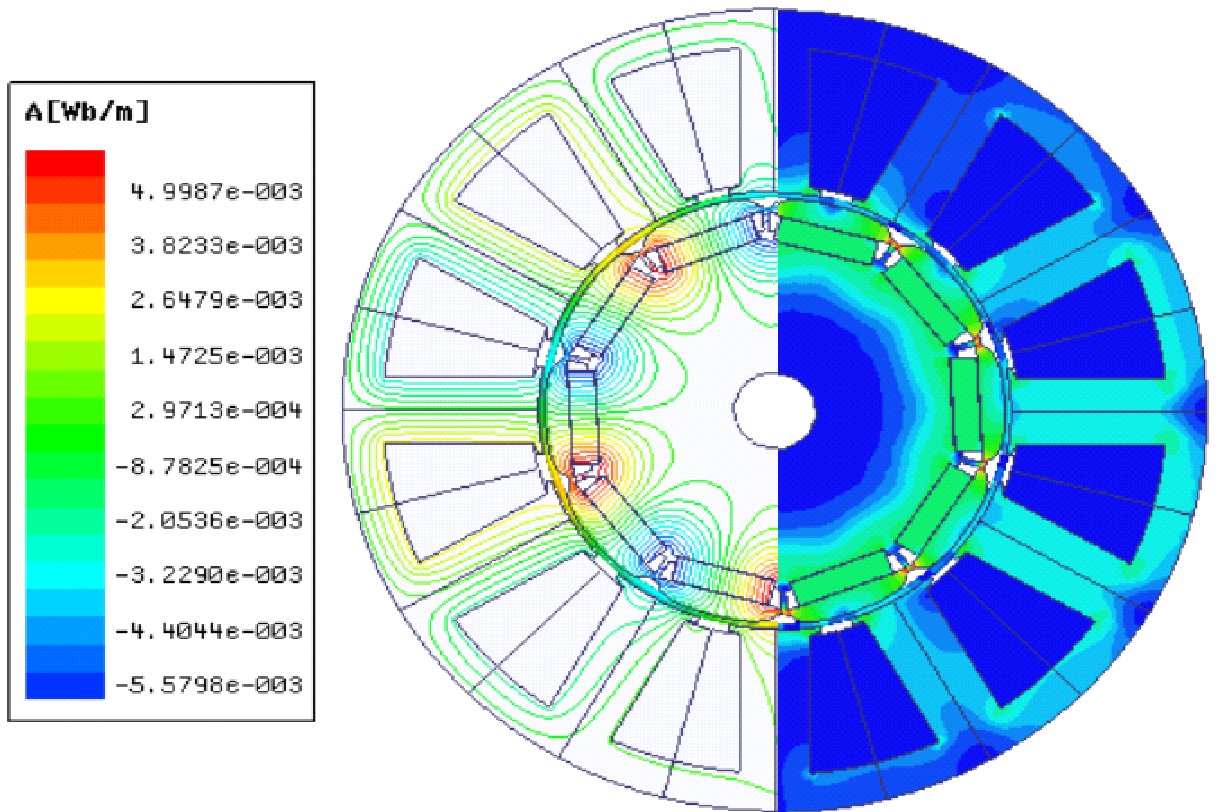

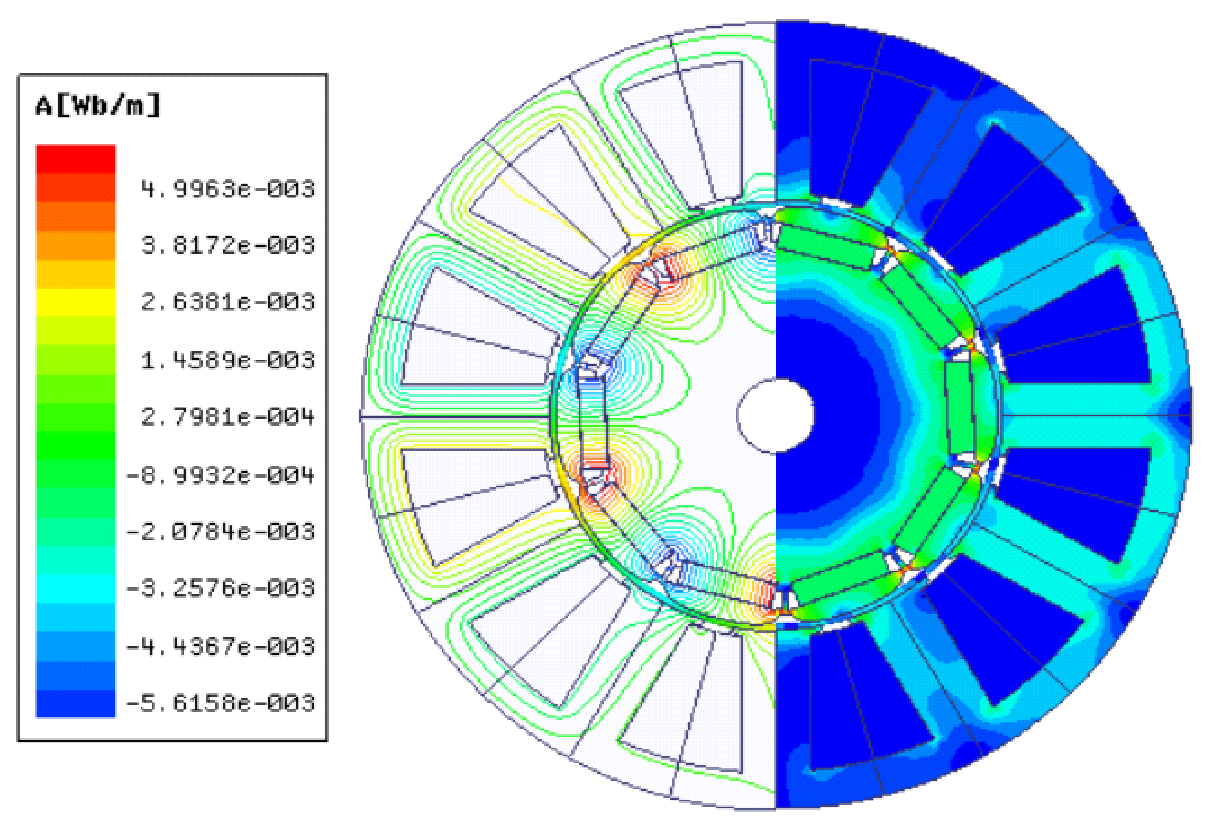

Figure 5 displays the machine's flux lines and flux density patterns with four different operation conditions: - healthy, PM diversity (the first case of Figure 2), static eccentricity, and dynamic eccentricities. The effect of the PM diversity and the eccentricities can be noted from the maximum flux value as shown in the Figure 5; the lower flux value is for the healthy machine, while the machine with diverse PM has the highest value, followed by the eccentric machine. This is because PM diversity was considered the maximum PM in this study. Br.

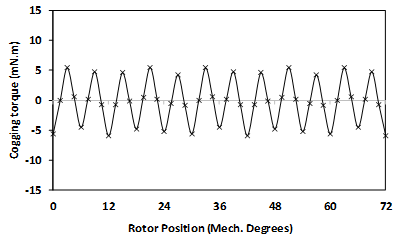

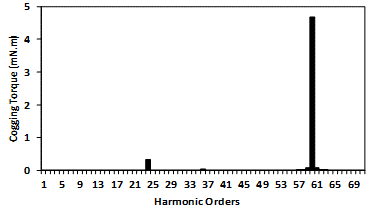

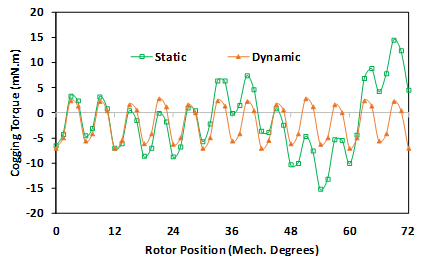

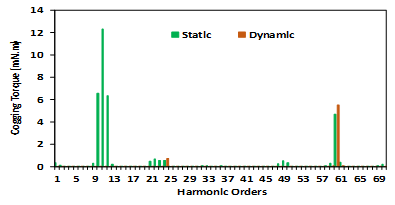

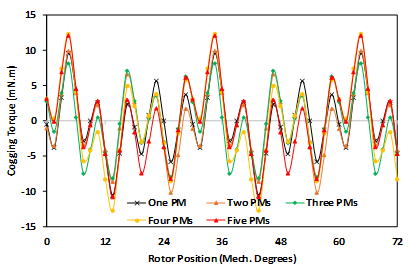

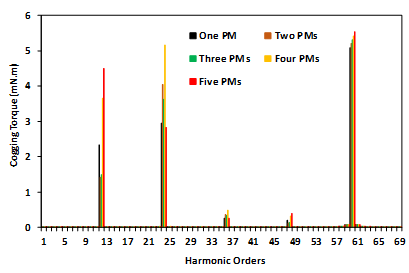

On the other hand, the air gap would not be uniform for both types of eccentricities, so there are areas where the air gap is smaller than the expected values, leading to increased magnetic flux. Cogging torque waveforms for one mechanical cycle and their FFT for all the understudying models are displayed in Figure 6 to Figure 8. Where Figure 6 shows the healthy case, Figure 7 is for static and dynamic cases, while Figure 8 compares the five cases of PM diversity. According to equation (2), the fundamental component of the cogging torque waveform should be in order 60, which is valid for a healthy motor. On the other hand, the 10th, 11th, and 12th harmonic orders are the demented harmonics for the motor with static eccentricity. Although the motor with dynamic eccentricity has cogging torque with a fundamental order harmonic of 60th, it delivers higher cogging torque than its healthy counterpart. Moreover, all the cogging torque waveforms of the motors with PM diversity have the 12th and its multiples order harmonics, as shown in Figure 8.

Table 1 compares the load performance of the understudying motors in terms of electromagnetic torque, i.e. (average value, maximum value, and minimum value) and torque ripples. Notably, both static eccentricity motor and motor with five PMs diversity deliver higher average torque than the other cases due to higher flux caused by the reduction of the airgap that faces one phase of the motor in case of static eccentricity and due to increasing the number of PMs that have diversity (which in this study represented by the higher value of the Br). Moreover, it can be seen that the lowest torque ripple is for the healthy case, followed by one PM diversity case, while the highest value of torque ripple is for the motor with five PM diversity cases, followed by the motor with static eccentricity.

Table 1. Load performance comparison of the understudying motor

Torque (N.m) | Average | Maximum | Minimum | Ripple (%) |

Healthy | 6.160 | 6.338 | 6.063 | 4.475 |

Static eccentricity | 8.148 | 8.505 | 7.954 | 6.759 |

Dynamic eccentricity | 6.423 | 6.578 | 6.336 | 5.338 |

One PM diverse | 6.506 | 6.728 | 6.396 | 5.105 |

Two PMs diverse | 6.566 | 6.783 | 6.437 | 5.277 |

Three PMs diverse | 6.618 | 6.829 | 6.469 | 5.440 |

Four PMs diverse | 6.666 | 6.927 | 6.527 | 5.996 |

Five PMs diverse | 8.615 | 9.074 | 8.360 | 8.284 |

|

|

(a) Healthy | (b) PM Diversity |

|

|

(c) Static | (d) Dynamic |

Figure 5. Flux lines and flux density patterns of the understudying machines

|

(a) Waveform |

|

(b) FFT |

Figure 6. Cogging torque of the healthy machine

|

(a) Waveform |

|

(b) FFT |

Figure 7. Cogging torque of eccentric machines

|

(a) Waveform |

|

(b) FFT |

Figure 8. Cogging torque of the machine with imperfect PMs

- COMPARATIVE WITH PREVIOUS WORKS

This section provides a compassion between the current paper and two previous papers, i.e. [29][30], which all interested in the investigation the influence of manufacturing tolerances on the torque ripple profile for IPM machines. The three papers consistent in using 2D-FEA to carry out the mentioned investigation. In contrasts, each paper has focused on specific rotor pole arc design. [29] carried out the mentioned investigation on the IPM machine with conventional rotor iron pole arc, while [30] preformed the same investigation on the IPM machines having eccentric and sinusoidal rotor iron pole arc. Moreover, in the current study such investigation has been performed on the IPM machines having sinusoidal with third order harmonic rotor iron pole arc. Regardless the rotor iron pole profiles, and considering the finding of the mentioned studies all have demonstrated that cogging torque profile of the IPM machines will have undesirable additional harmonics due to the imperfection mass-production assembly.

- CONCLUSIONS

The impact of rotor manufacturing tolerances on the performance of IPM motors with a sinusoidal + third-order harmonic injected rotor iron pole shape has been examined, focusing on cogging torque and torque ripple. This study explicitly addresses two types of rotor manufacturing tolerances: rotor eccentricity and PM diversity. The analysis employed 2D-FEA method. In addition to a baseline healthy model, seven models were designed to simulate various scenarios of the rotor eccentricity and the PM diversity. A comparative analysis of the simulation results was conducted. It was found that besides the fundamental (60th) harmonic of the cogging torque waveform in the healthy motor, motors with eccentricities and PM diversities introduced additional harmonic orders. All cogging torque waveforms from motors with PM diversity included the 12th harmonic and its multiples. Moreover, the motor with the static eccentricity exhibited more low orders harmonic than that the with dynamic eccentricity. According to the obtained results, it has been noted that the static eccentricity causes more torque ripple, highest cogging torque and crates high low order harmonic compared to the dynamic eccentricity, and the PM imperfections. Therefore, compact tolerances guarantee on the rotor symmetry and assembly alignment is more crucial for precision performance than nonuniformity of the permanent magnet properties.

REFERENCES

- M. Sagawa, S. Fujimura, N. Togawa, H. Yamamoto and Y. Matsuura, "New material for permanent magnets on a base of Nd and Fe (Invited)," Journal of Applied Physics, vol. 55, no. 6, pp. 2083-2087, 1984, https://doi.org//10.1063/1.333572.

- J. J. Croak, J. F. Herbsf, R. W. Lee, and F. E. Pinkerton, "High- Energy product Nd-Fe-B permanent magnet," Appl. Phys. Lett, vol. 44, no. I, pp. 148-149, 1984, https://doi.org//10.1063/1.94584.

- T. Mizoguchi, I. Sakai, H. Niu, and K. Inomata, "Nd-Fe-B-CO-AI based permanent magnets with improved magnetic properties and temperature characteristics," Appl. Phys. Lett., vol.48, no. 5, pp. 1309–1310, 1986, https://doi.org//10.1063/1.96962.

- S. Murthy, B. Derouane, B. Liu and T. Sebastian, "Minimization of torque pulsations in a trapezoidal back-EMF permanent magnet brushless DC motor," Conference Record of the 1999 IEEE Industry Applications Conference. Thirty-Forth IAS Annual Meeting (Cat. No.99CH36370), vol. 2, pp. 1237-1242, 1999, https://doi.org/10.1109/IAS.1999.801661.

- M. Zheng, Z. Q. Zhu, S. Cai and S. S. Xue, "A Novel Modular Stator Hybrid-Excited Doubly Salient Synchronous Machine With Stator Slot Permanent Magnets," IEEE Transactions on Magnetics, vol. 55, no. 7, pp. 1-9, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/TMAG.2019.2902364.

- N. Bianchi, E. Fornasiero and W. Soong, "Selection of PM Flux Linkage for Maximum Low-Speed Torque Rating in a PM-Assisted Synchronous Reluctance Machine," IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, vol. 51, no. 5, pp. 3600-3608, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1109/TIA.2015.2416236.

- T. Li and G. Slemon, "Reduction of cogging torque in permanent magnet motors," IEEE Transactions on Magnetics, vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 2901-2903, 1988, https://doi.org/10.1109/20.92282.

- S. Hwang and D. K. Lieu, "Design techniques for reduction of reluctance torque in brushless permanent magnet motors," IEEE Transactions on Magnetics, vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 4287-4289, 1994, https://doi.org/10.1109/20.334063.

- K. Ohnishi, "Cogging torque reduction in permanent magnet brushless motors" (in Japanese), T. IEE Japan, vol. 122-d, no. 4, 2002, https://doi.org//10.1541/ieejias.122.338.

- N. Matumoto, S. Nishimura, M. Sanada, S. Morimoto and Y. Takeda, "Torque performances and arrangement of permanent magnet for IPMSM" (in Japanese), The Papers of Technical Meeting on Rotating Machinery, IEE Japan, RM-04-52, 2004, https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1570572700418166144.

- T. M. Jahns and W. L. Soong, "Pulsating torque minimization techniques for permanent magnet ac motor drives: A review," IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 321-330, 1996, https://doi.org/10.1109/41.491356.

- M. S. Islam, S. Mir, and T. Sebastian, "Issues in reducing the cogging torque of mass-produced permanent-magnet brushless DC motor," IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 813-820, 2004, https://doi.org/10.1109/TIA.2004.827469.

- L. Zhu, S. Z. Jiang, Z. Q. Zhu and C. C. Chan, "Analytical methods for minimizing cogging torque in permanent-magnet machines," IEEE Transactions on Magnetics, vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 2023-2031, 2009, https://doi.org/10.1109/TMAG.2008.2011363.

- S. Leitner, H. Gruebler and A. Muetze, "Cogging Torque Minimization and Performance of the Sub-Fractional HP BLDC Claw-Pole Motor," IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, vol. 55, no. 5, pp. 4653-4664, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/TIA.2019.2923569.

- M. García-Gracia, Á. Jiménez Romero, J. Herrero Ciudad, and S. Martín Arroyo, “Cogging Torque Reduction Based on a New Pre-Slot Technique for a Small Wind Generator,” Energies, vol. 11, no. 11, p. 3219, 2018, https://doi.org/10.3390/en11113219.

- Z. Goryca, S. Różowicz, A. Różowicz, A. Pakosz, M. Leśko, and H. Wachta, “Impact of Selected Methods of Cogging Torque Reduction in Multipolar Permanent-Magnet Machines,” Energies, vol. 13, no. 22, p. 6108, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/en13226108.

- C. Gan, J. Wu, M. Shen, W. Kong, Y. Hu and W. Cao, "Investigation of Short Permanent Magnet and Stator Flux Bridge Effects on Cogging Torque Mitigation in FSPM Machines," IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 845-855, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1109/TEC.2017.2777468.

- J. Gao, Z. Xiang, L. Dai, S. Huang, D. Ni and C. Yao, "Cogging Torque Dynamic Reduction Based on Harmonic Torque Counteract," IEEE Transactions on Magnetics, vol. 58, no. 2, pp. 1-5, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/TMAG.2021.3093723.

- J. R. Hendershot and T. J. E. Miller, "Design of brushless permanent magnet motors," Magna Physics Publishing & Clarendon Press, 1994, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198593898.001.0001.

- N. Levin, S. Orlova, V. Pugachov, B. Ose-Zala, E. Jakobsons, "Methods to Reduce the Cogging Torque in Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines,” Electron. Electr. Eng, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 23–26, 2013, https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.eee.19.1.3248.

- S. A. Evans, "Salient pole shoe shapes of interior permanent magnet synchronous machines," The XIX International Conference on Electrical Machines - ICEM 2010, pp. 1-6, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICELMACH.2010.5607694.

- Z. S. Du and T. A. Lipo, "Efficient Utilization of Rare Earth Permanent-Magnet Materials and Torque Ripple Reduction in Interior Permanent-Magnet Machines," IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 3485-3495, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1109/TIA.2017.2687879.

- K. Wang, Z. Q. Zhu, G. Ombach, and W. Chlebosz, "Average torque improvement of interior permanent-magnet machine using third harmonic in rotor shape," IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 61, no. 9, pp. 5047-5057, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2013.2286085.

- A. J. Piña, S. Paul, R. Islam and L. Xu, "Effect of manufacturing variations on cogging torque in surface-mounted permanent magnet motors," 2015 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), pp. 4843-4850, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1109/ECCE.2015.7310343.

- H. Qian, H. Guo, Z. Wu and X. Ding, "Analytical Solution for Cogging Torque in Surface-Mounted Permanent-Magnet Motors with Magnet Imperfections and Rotor Eccentricity," IEEE Transactions on Magnetics, vol. 50, no. 8, pp. 1-15, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1109/TMAG.2014.2312179.

- L. Gasparin, A. Cernigoj, S. Markic and R. Fiser, "Additional Cogging Torque Components in Permanent-Magnet Motors Due to Manufacturing Imperfections," IEEE Transactions on Magnetics, vol. 45, no. 3, pp. 1210-1213, 2009, https://doi.org/10.1109/TMAG.2009.2012561.

- M. Nakano, Y. Morita and T. Matsunaga, "Reduction of cogging torque due to production tolerances of rotor by using partially placed dummy slots in axial direction," 2014 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), pp. 5579-5586, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1109/ECCE.2014.6954165.

- I. Coenen, M. van der Giet and K. Hameyer, "Manufacturing Tolerances: Estimation and Prediction of Cogging Torque Influenced by Magnetization Faults," IEEE Transactions on Magnetics, vol. 48, no. 5, pp. 1932-1936, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1109/TMAG.2011.2178252.

- X. Ge and Z. Q. Zhu, "Sensitivity of manufacturing tolerances on cogging torque in interior permanent magnet machines with different Slot/Pole number combinations," IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 3557-3567, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1109/TIA.2017.2693258.

- X. Ge and Z. Q. Zhu, "Influence of manufacturing tolerances on cogging torque in interior permanent magnet machines with eccentric and sinusoidal rotor contours," IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 3568-3578, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1109/TIA.2017.2693264.

- Z. Q. Zhu and D. Howe, "Influence of design parameters on cogging torque in permanent magnet machines," in IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 407-412, 2000, https://doi.org/10.1109/60.900501.

Ahlam Luaibi Shuraiji (Investigation of Manufacture Tolerances on Torque Pulsation Profile of Interior Permanent Magnet Motor with Third Harmonic Injected Sinusoidal Rotor Iron Pole)