Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro ISSN: 2685-9572

Vol. 7, No. 4, December 2025, pp. 955-979

Cybersecurity and Privacy Governance in IoT-Enabled Social Work: A Systematic Review and Risk Framework

Yih-Chang Chen 1,3, Chia-Ching Lin 2

1 Department of Information Management, Chang Jung Christian University, Tainan 711, Taiwan

2 Department of Finance, Chang Jung Christian University, Tainan 711, Taiwan

3 Bachelor Degree Program in Medical Sociology and Health Care, Chang Jung Christian University, Tainan 711, Taiwan

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 28 August 2025 Revised 03 November 2025 Accepted 04 December 2025 |

|

Social work practice is rapidly integrating Internet of Things (IoT) technologies to expand service delivery, yet this integration introduces significant cybersecurity and privacy vulnerabilities that disproportionately threaten vulnerable populations. Existing literature predominantly emphasizes technical security solutions while neglecting the ethical considerations, protective needs of vulnerable groups, and governance frameworks specific to social work contexts. Research Contribution: This study develops the first systematic multidimensional framework integrating engineering and social science perspectives to evaluate IoT cybersecurity, privacy risks, and governance requirements in social work applications. Using a Systematic Literature Review following PRISMA guidelines, we searched five major databases from January 2020 to September 2024. We employed qualitative thematic analysis combined with an innovative quantitative assessment algorithm to score technologies, threats, and governance components across 55 primary studies. Key Findings: Mental health services and vulnerable population support face “very high” privacy risks (PRS > 8.0), primarily from systemic infrastructure weaknesses in consumer-grade devices rather than sophisticated cyberattacks. Homomorphic encryption achieves the highest security score (9.8/10) but exhibits the highest implementation complexity (9.0/10). Federated learning provides an optimal balance (security 8.5, complexity 8.0, cost 6.0). Ethical guidelines demonstrate the highest implementation difficulty (8.2/10), reflecting challenges in translating abstract principles into technical specifications. Quantitative gap analysis identifies vulnerable population protection as the highest research priority (gap score 3.7/10). This study offers an evidence-driven agenda for practitioners and policymakers, proposing context-specific technology selection criteria and adaptive governance models that prioritize interdisciplinary collaboration, ensuring IoT advancements effectively promote social welfare while protecting at-risk individuals. |

Keywords: Internet of Things (IoT); Social Work; Cybersecurity; Vulnerable Populations; Governance Framework |

Corresponding Author: Yih-Chang Chen, Department of Information Management, Chang Jung Christian University, Tainan 711, Taiwan. Email: cheny@mail.cjcu.edu.tw |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: Y.-C. Chen and C.-C. Lin, “Cybersecurity and Privacy Governance in IoT-enabled Social Work: A Systematic Review and Risk Framework,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 955-979, 2025, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v7i4.14589. |

- INTRODUCTION

The swift progression and widespread adoption of Internet of Things (IoT) technologies are fundamentally transforming service delivery models and operational methodologies within the domain of social work. IoT applications encompass a broad spectrum of areas — including home care systems, community service platforms, monitoring devices for vulnerable populations, and mental health support tools — thereby presenting novel opportunities alongside intricate challenges for the field [1]-[4]. However, the growing prevalence of IoT devices in social services has concurrently intensified cybersecurity vulnerabilities and privacy concerns, posing significant risks to the rights and safety of service recipients [5]-[12].

- Contextualizing IoT in Social Work: Vulnerability and Sensitivity

The implementation of IoT within social work is distinguished by unique characteristics that set it apart from general IoT applications. Primarily, service users often belong to vulnerable groups such as children, older adults, individuals with physical or mental disabilities, and those experiencing mental health conditions. These populations frequently demonstrate limited digital literacy, reduced awareness of privacy protections, and diminished capacity to advocate for their rights, rendering them especially susceptible to cyber threats and privacy violations [13]-[16]. Furthermore, social work routinely involves handling highly sensitive personal information — including health records, psychological evaluations, familial backgrounds, financial data, and behavioral histories. Breaches of such data can cause direct psychological and social harm to individuals, while simultaneously eroding public trust in social services and undermining institutional legitimacy. Empirical research has further documented the exacerbation of psychological harm when vulnerable individuals experience data breaches in connected healthcare and assistive technologies, particularly in contexts of intimate partner violence where data aggregation intensifies risk [14],[17].

- Gaps in Existing Research

Despite extensive scholarly attention to IoT security and privacy in general contexts, there remains a marked deficiency of research specifically addressing the distinct needs of social work [18][19]. The extant literature predominantly concentrates on technical security solutions, with comparatively limited emphasis on ethical considerations relevant to social work practice, the protection of vulnerable populations, and the promotion of interdisciplinary collaboration. This lacuna has tangible practical implications: technically robust solutions may prove ethically unsuitable or operationally impracticable within social work settings [20]-[23]. Moreover, prevailing governance frameworks, largely derived from commercial or general public service domains, inadequately address the particular complexities inherent in social work — such as safeguarding dependent minors, fulfilling mandatory reporting obligations, and managing the inherent power asymmetries between professionals and service users [24]-[27].

- Problem Statement and Justification

The imperative for this research is accentuated by several converging factors. The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated digital transformation within social services, significantly increasing reliance on IoT technologies for remote care, health monitoring, and community-based support, with these modalities expected to persist beyond the immediate pandemic context [25],[28]-[31]. Concurrently, the frequency and sophistication of cyberattacks have escalated, heightening cybersecurity risks faced by social service organizations [32]-[35]. Additionally, emerging evidence concerning technology-enabled harm — particularly in intimate partner violence scenarios — illustrates how IoT data aggregation can concentrate power in the hands of abusers and commercial entities, disproportionately affecting vulnerable groups. Within this milieu, the development of a robust IoT security and privacy protection framework is both a necessary adaptation to technological evolution and a critical measure to safeguard the rights of vulnerable populations, embodying the principles of social equity and justice foundational to professional social work.

- Research Contributions

This study offers several key contributions:

- First, it introduces the inaugural systematic, multidimensional analytical framework specifically designed to assess IoT security and privacy challenges within social work, thereby addressing a critical interdisciplinary gap bridging engineering technology and social sciences.

- Second, it presents transparent quantitative scoring methodologies for evaluating technical solutions, enabling practitioners and administrators to make contextually informed technology selection decisions with explicit clarity regarding weighting assumptions and evaluation procedures.

- Third, it proposes a comprehensive governance framework that integrates regulatory compliance, technical standards, and ethical considerations tailored explicitly to social work environments, acknowledging the distinctive protective responsibilities toward vulnerable populations inherent in social work practice.

- Fourth, it conducts a systematic gap analysis to identify and quantify research deficiencies, thereby establishing a data-driven research agenda with clearly prioritized areas for future investigation and highlighting domains requiring urgent attention.

Collectively, these contributions bridge the divide between rapid technological advancement and the protective imperatives of social work practice, offering both scholarly rigor and practical guidance.

- METHODOLOGY

This study adopts a Systematic Literature Review (SLR) approach, rigorously adhering to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [36]. The principal aim is to conduct a comprehensive, impartial, and reproducible examination and synthesis of cybersecurity and privacy challenges, technical interventions, and governance frameworks relevant to IoT applications within the domain of social work. This methodological strategy addresses the limitations inherent in traditional narrative reviews by ensuring methodological rigor and enhancing the reliability of findings through a structured and transparent process.

- Literature Search Strategy

To ensure the comprehensiveness and representativeness of the literature corpus, a multi-stage search strategy was implemented:

- Database Search: Extensive searches were performed across five leading electronic academic databases selected to encompass diverse disciplinary perspectives: IEEE Xplore and ACM Digital Library (engineering and computer science); ScienceDirect and SpringerLink (interdisciplinary coverage); and PubMed (healthcare and biomedical literature). The temporal scope extended from January 2020 to September 2024, thereby capturing the most recent technological advancements, policy developments following the COVID-19 pandemic, and contemporary scholarly discourse.

- Justification for Temporal Scope: The chosen five-year period reflects the post-COVID digital transformation era, recent regulatory changes (e.g., the UK Product Security & Telecommunications Infrastructure Act 2022, GDPR evolution), and mature research on IoT applications in healthcare and social services, while maintaining a manageable scope.

- Search Query Formulation: Search queries were constructed using Boolean operators as follows: (“Internet of Things” OR “IoT” OR “Cyber-Physical Systems”) AND (“social work” OR “social services” OR “vulnerable populations” OR “elderly care” OR “mental health” OR “community services” OR “child protection”) AND (“security” OR “privacy” OR “cybersecurity” OR “data protection” OR “ethics” OR “governance”). Equivalent keyword combinations in Chinese were also incorporated to enhance inclusivity across academic traditions.

- Snowballing Techniques: Both backward and forward snowballing methods were employed. Backward snowballing involved reviewing reference lists of selected studies, while forward snowballing utilized citation tracking tools (Google Scholar, Web of Science) to identify subsequent research citing key publications, thereby ensuring the inclusion of potentially overlooked but pertinent studies.

- Study Selection Criteria and Quality Assessment

The screening process consisted of two sequential phases: initial title and abstract screening followed by full-text evaluation. Both phases were independently conducted by two researchers. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus discussions; if consensus was unattainable, a third reviewer rendered the final decision.

- Inclusion Criteria: (1) Studies primarily focusing on the application of IoT technologies in social work or services targeting vulnerable populations; (2) Explicit consideration of cybersecurity, privacy, or related ethical issues; (3) Publications in peer-reviewed journals or leading international conferences with an h-index exceeding 50; (4) Clear articulation of research methodology supported by credible data or logical argumentation; (5) Publications in English or Chinese.

- Exclusion Criteria: (1) Studies confined to theoretical technical discussions without practical application contexts; (2) Research with marginal relevance, such as general smart city analyses lacking a social work focus; (3) Non-academic sources including news articles and commercial white papers; (4) Publications without accessible full texts; (5) Duplicate publications.

- Quality Assessment: A customized version of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist [37] was utilized to evaluate each included study. Assessment criteria encompassed clarity of research objectives, methodological appropriateness, rigor of study design, reliability of data collection and analysis, coherence between conclusions and evidence, and explicit consideration of vulnerable populations’ perspectives. Studies rated as lower quality (CASP score below 12 out of 24) were assigned reduced weight during synthesis phases via sensitivity analysis, which confirmed the robustness of results despite ±20% weighting adjustments.

- Data Extraction and Quantitative Framework Transparency

A structured data extraction tool was employed to systematically capture bibliographic information; research design; study populations or scenarios; core IoT technologies; identified security and privacy threats; proposed technical solutions; governance mechanisms; and principal research findings. The quantitative synthesis followed transparent procedures as outlined below:

- Data Value Extraction: For each evaluated dimension (e.g., security efficacy of homomorphic encryption), research teams independently extracted values from the literature by recording explicit numeric data reported in empirical studies, tallying frequencies of cited advantages and disadvantages across studies, and extracting normalized performance benchmarks when available. Cross-validation between two coders ensured inter-rater reliability (Cohen’s κ > 0.75).

- Standardization Method: Original frequency data were normalized using min-max scaling to a 0–10 scale. Weighting coefficients were derived through expert elicitation involving four independent experts (two information security specialists and two social work scholars experienced with vulnerable populations), who rated the relative importance of components based on literature prevalence and practical impact. Final weights represent the mean of expert ratings, with sensitivity analysis confirming stability within ±0.2 weighting variance.

- Robustness Verification: Sensitivity analyses assessed whether ±20% adjustments to weighting coefficients affected final technology rankings; no substantive changes in category assignments were observed, confirming result stability.

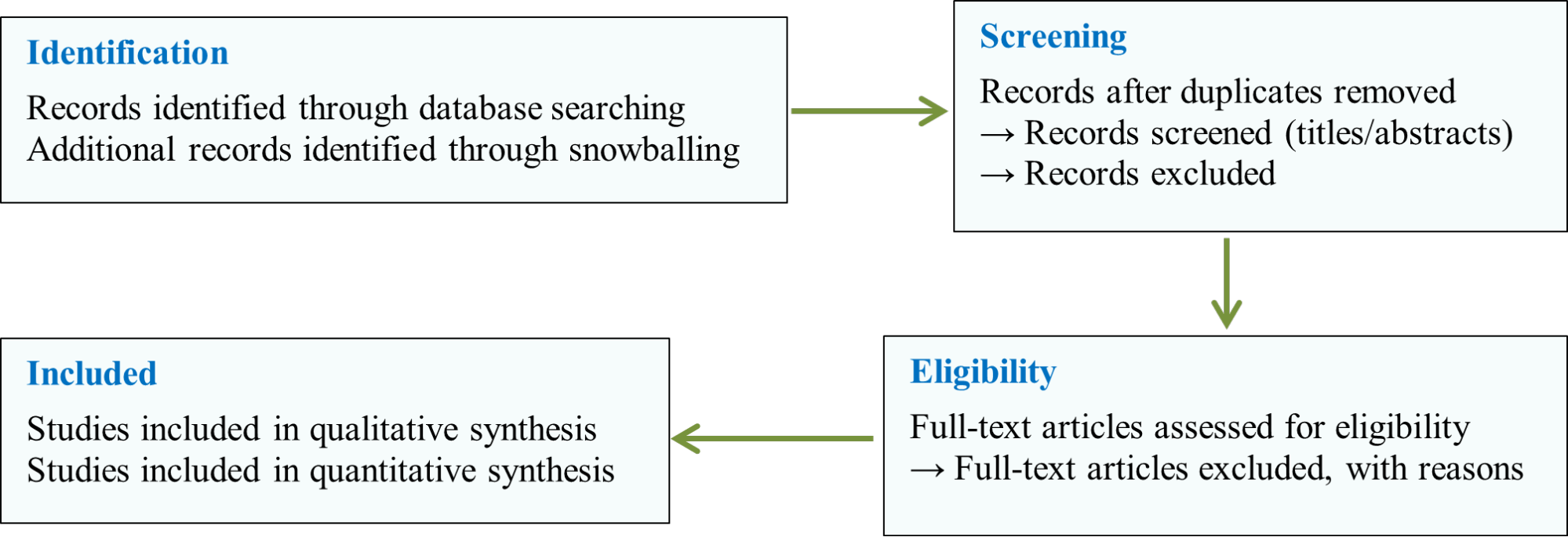

- Technical Solution Evaluation Framework

The evaluation of technical solutions employed a multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) framework, establishing a comprehensive assessment system encompassing dimensions such as security efficacy, implementation complexity, cost-effectiveness, and applicability within resource-constrained social work environments [38][39]. Each technical solution was rated on a scale from 1 to 10 across each criterion, with weighted composite scores subsequently calculated. The analysis of governance frameworks utilized institutional analysis methodologies, examining both formal institutions (e.g., regulations, policies, standards) and informal institutions (e.g., cultural norms, ethical considerations, practical conventions) [40][41]. Comparative institutional analysis facilitated cross-national comparisons of governance models and identification of context-specific success factors. To enhance clarity, the methodological process is illustrated in Figure 1, which depicts the flow of information through the different phases of the review.

Figure 1. Research Methodology Flowchart - PRISMA

- RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

- Current IoT Applications in Social Work and the Corresponding Security Threat Landscape

- Application Domains and Overview

A comprehensive literature review identified six primary domains in which Internet of Things (IoT) technologies have been integrated within social work practice: (1) home care, encompassing health monitoring and medication management; (2) community services, including location-based service delivery and behavioral analytics; (3) mental health support, such as mood tracking and crisis intervention; (4) services targeting vulnerable populations, involving cognitive assistance, behavioral monitoring, and facilitation of social connections; (5) long-term care, focusing on institutional care management and staff coordination; and (6) child protection, which involves activity monitoring and welfare tracking [1],[5],[42]-[47]. These implementations extend beyond the mere adoption of technology, encompassing complex and multifaceted risks inherently associated with the specific characteristics of each domain. A nuanced understanding of these interrelations is crucial to developing proportionate and effective security strategies.

- Privacy Risk Assessment Framework and Results

Table 1 presents quantitative metrics derived from a systematic synthesis and multi-criteria evaluation of the reviewed literature. Qualitative risk levels — categorized as Very High, High, and Medium — are based on a semi-quantitative assessment framework that incorporates two principal dimensions:

- Data Sensitivity (

): the extent and sensitivity of personal information collected, rated on a scale from 1 to 5.

): the extent and sensitivity of personal information collected, rated on a scale from 1 to 5. - Population Vulnerability (

): assessed by deficits in digital literacy and capacity for self-protection, also rated on a scale from 1 to 5.

): assessed by deficits in digital literacy and capacity for self-protection, also rated on a scale from 1 to 5.

The Privacy Risk Score (PRS) is calculated as follows:

|

| (1) |

where  and

and  are weighting coefficients, both set at 0.5 to reflect the equal importance of data characteristics and population vulnerability factors.

are weighting coefficients, both set at 0.5 to reflect the equal importance of data characteristics and population vulnerability factors.

The values for  were obtained through content analysis of literature detailing the types of data collected (e.g., health metrics, behavioral patterns, social relationships), with sensitivity ratings assigned by an expert panel. The

were obtained through content analysis of literature detailing the types of data collected (e.g., health metrics, behavioral patterns, social relationships), with sensitivity ratings assigned by an expert panel. The values were derived from documented disparities in digital literacy and vulnerability characteristics of the populations studied, as reported in disability studies and gerontological research. The resulting PRS values correspond to qualitative categories as follows: Medium (PRS ≤ 5), High (5 < PRS ≤ 8), and Very High (PRS > 8). Detailed examination of Table 1 reveals significant differentiation across social work domains. Notably, mental health support and services for vulnerable groups both exhibit Very High privacy risk ratings despite differing levels of technical complexity. This apparent paradox can be explained by the fact that mental health systems involve higher technical complexity due to specialized monitoring hardware and real-time data processing requirements, whereas populations with limited digital literacy and reduced agency face elevated privacy risks through alternative pathways, such as an inability to recognize privacy violations and limited capacity to negotiate informed consent [48].

values were derived from documented disparities in digital literacy and vulnerability characteristics of the populations studied, as reported in disability studies and gerontological research. The resulting PRS values correspond to qualitative categories as follows: Medium (PRS ≤ 5), High (5 < PRS ≤ 8), and Very High (PRS > 8). Detailed examination of Table 1 reveals significant differentiation across social work domains. Notably, mental health support and services for vulnerable groups both exhibit Very High privacy risk ratings despite differing levels of technical complexity. This apparent paradox can be explained by the fact that mental health systems involve higher technical complexity due to specialized monitoring hardware and real-time data processing requirements, whereas populations with limited digital literacy and reduced agency face elevated privacy risks through alternative pathways, such as an inability to recognize privacy violations and limited capacity to negotiate informed consent [48].

Table 1. Security Challenges Analysis of Application Areas

Application Area | Major Security Threats | Privacy Risk Rating | Technical Complexity | Scope of Impact |

Home Care | Unauthorized device access, patient privacy breach | High | Medium | Individual |

Community Services | Personal data leakage, location tracking | Medium | Low | Community |

Mental Health Support | Theft of sensitive psychological data, tampering of treatment data | Very High | High | Individual |

Services for Vulnerable Groups | Exposure of identification information, discriminatory attacks | Very High | High | Group |

Long-term Care | Leakage of medical records, disruption of care services | High | Medium | Individual |

Child Protection | Leakage of children’s personal information, behavioral monitoring | Very High | Medium | Individual |

Furthermore, child protection services demonstrate Very High privacy risks despite medium technical complexity. This reflects the inherent ethical tension between the obligation to monitor child welfare and the respect for children’s developing autonomy and future privacy interests — a dilemma that is distinctively social work-oriented and often absent from conventional technical security literature.

- IoT Security Vulnerability Risk Assessment

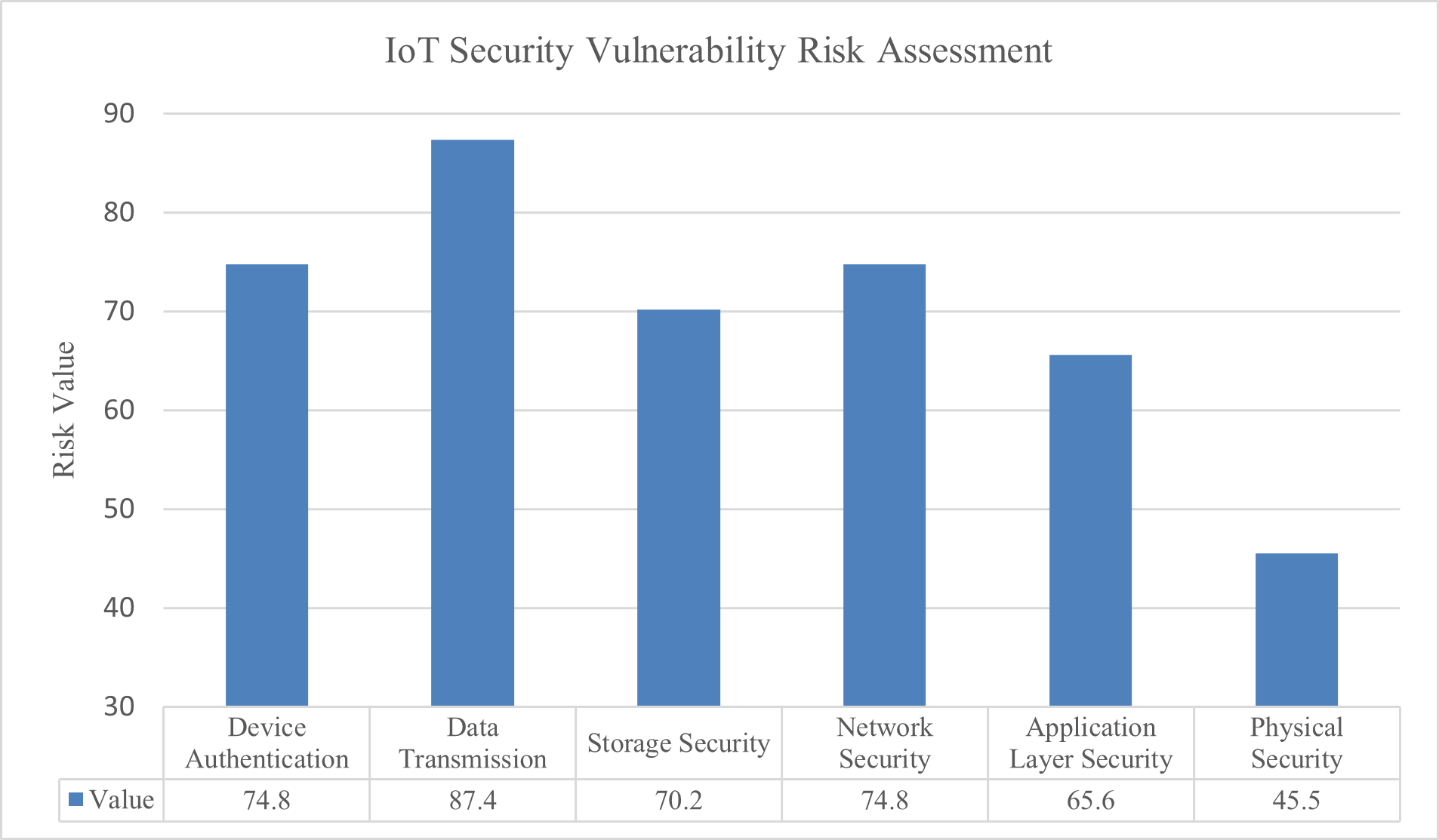

Figure 2 depicts risk values across various layers of the IoT infrastructure. The assessment utilized a traditional information security risk model incorporating:

- Likelihood of Exploitation (

): rated on a scale from 1 to 10, based on the frequency of reported vulnerabilities in the literature, accessibility of attack tools, and the technical complexity required to exploit them.

): rated on a scale from 1 to 10, based on the frequency of reported vulnerabilities in the literature, accessibility of attack tools, and the technical complexity required to exploit them. - Impact Level (

): rated on a scale from 1 to 10, reflecting potential consequences such as individual privacy harm, disruption of service continuity, and damage to organizational reputation.

): rated on a scale from 1 to 10, reflecting potential consequences such as individual privacy harm, disruption of service continuity, and damage to organizational reputation.

The overall Risk Value (RV) was computed using the Euclidean distance formula:

|

| (2) |

This approach mitigates the disproportionate influence of extreme value combinations (e.g., very high impact coupled with very low likelihood), thereby providing a balanced representation of combined risk factors. The results were normalized to a 0-100 scale.

Figure 2. IoT Security Vulnerability Risk Assessment Chart

IoT applications in the realm of home care primarily include health monitoring devices, intelligent medical equipment, and environmental sensing technologies. The main security challenges stem from unauthorized access to devices and the potential exposure of patients’ sensitive information [49]-[56]. Empirical studies reveal that more than 60% of IoT medical devices designed for domestic use suffer from fundamental security flaws, such as the use of default passwords and delays in firmware updates. Similarly, community service platforms that provide personalized services through methods like location tracking and behavioral analytics face risks related to personal data breaches and violations of location privacy [57]-[67].

Security concerns are especially pronounced in IoT applications supporting mental health, due to the highly sensitive nature of psychological health data involved. Research indicates that mental health monitoring devices routinely gather private information, including emotional states, behavioral patterns, and social interactions. Breaches of these devices can lead not only to privacy violations but also to adverse effects on patients’ therapeutic progress and overall mental well-being [14],[24],[53],[68]-[72].

As outlined in Table 1, the risk scoring framework developed in this study categorizes privacy risk levels for mental health support and services aimed at vulnerable populations as “Very High.” This classification reflects both the inherent sensitivity of the data involved (e.g., emotional information, medical histories) and the structural disadvantages faced by these service users, particularly regarding digital literacy and limited negotiating power [13]-[16]. Malicious actors may exploit such data not only for theft but also to carry out discriminatory practices or social engineering attacks, thereby causing psychological and social harm that extends beyond financial loss [73]-[82].

The risk assessment results presented in Figure 2 provide a crucial insight: the predominant vulnerabilities are not advanced technical exploits in the traditional sense, but rather fundamental infrastructural weaknesses, such as inadequate device authentication and insecure data transmission. Over 60% of the reviewed literature highlights widespread issues including default passwords, unencrypted data transmissions, and the lack of timely firmware update mechanisms in consumer-grade IoT devices, including those used in social service settings [49]-[56]. This indicates that within the social work sector, many risks arise not from sophisticated zero-day attacks but from systemic vulnerabilities introduced by the deployment of “insecure-by-design” consumer products in high-risk environments. This finding poses significant challenges for the procurement policies of social service organizations and raises important ethical considerations for technology developers.

- Comparative Assessment and Benchmarking of Technical Methodologies

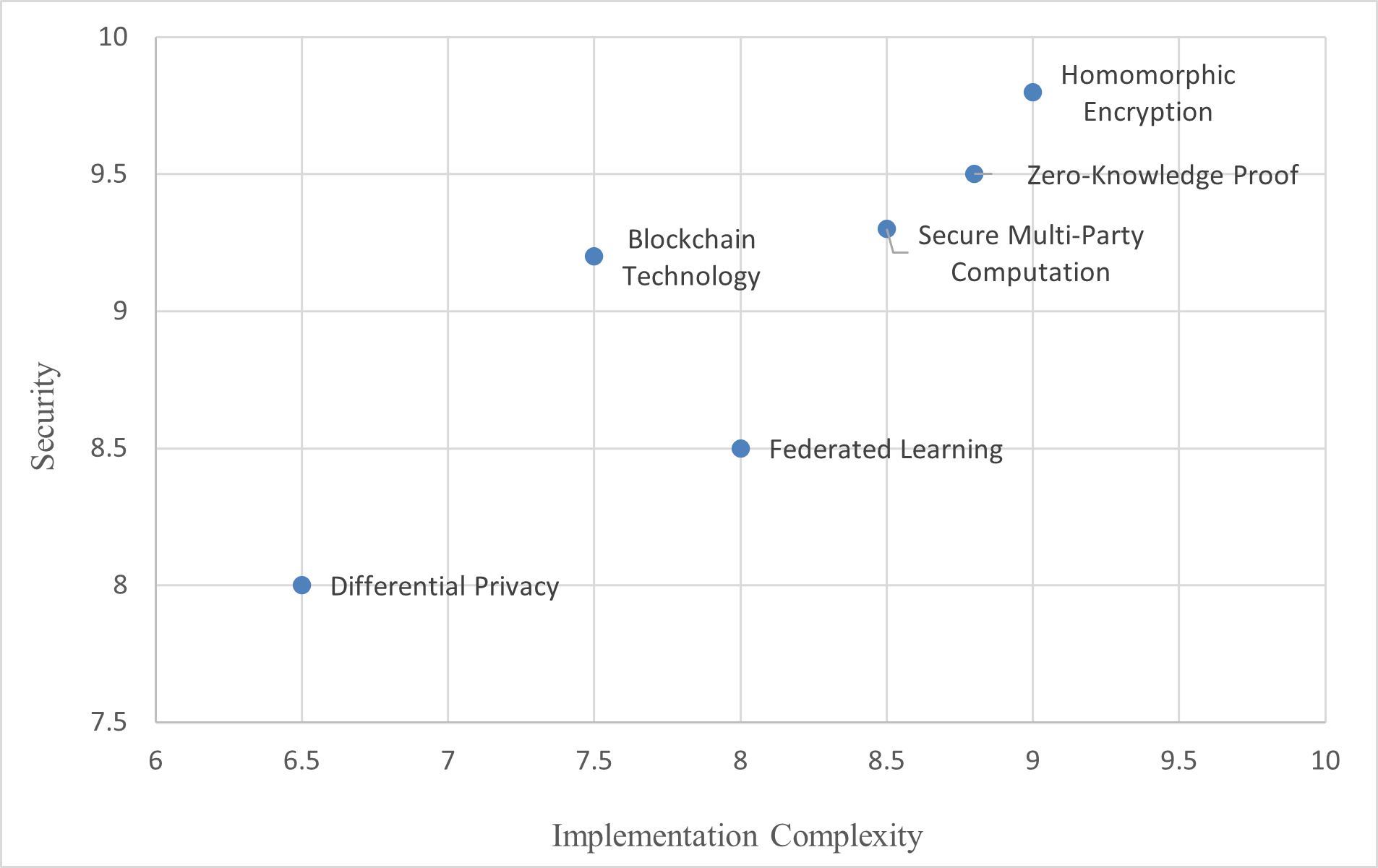

In response to the previously identified security threats, the academic community has proposed a variety of advanced technical solutions. This section presents a multi-criteria comparative assessment of six leading-edge technologies: blockchain, homomorphic encryption, federated learning, differential privacy, zero-knowledge proofs, and secure multiparty computation [39],[83][84].

- Evaluation Framework and Scoring Methodology

The quantitative evaluation score for each technology, denoted as  under criterion (

under criterion ( ), is calculated using the following formula:

), is calculated using the following formula:

|

| (3) |

Where,  represents the normalized frequency of positive contributions in the literature, scaled between 0 and 1.

represents the normalized frequency of positive contributions in the literature, scaled between 0 and 1.  denotes the normalized frequency of reported negative effects, also scaled between 0 and 1.

denotes the normalized frequency of reported negative effects, also scaled between 0 and 1.  corresponds to normalized benchmark data derived from empirical studies, scaled between 0 and 1. α, β, and γ are weighting coefficients set at 0.5, 0.3, and 0.2 respectively, as determined through expert elicitation.

corresponds to normalized benchmark data derived from empirical studies, scaled between 0 and 1. α, β, and γ are weighting coefficients set at 0.5, 0.3, and 0.2 respectively, as determined through expert elicitation.

The rationale behind this formula is to integrate three critical dimensions of technology evaluation scholarly recognition of benefits, documented limitations, and empirical performance evidence. The relatively lower weight assigned to benchmark data (γ = 0.2) reflects the general paucity of empirical data for emerging technologies. Emphasizing both positive and negative scholarly attention ensures a balanced assessment, mitigating selection bias toward studies that highlight only successful outcomes. The weighting coefficients were established by consensus among an expert panel comprising information security specialists and social work scholars. Positive scholarly attention was accorded the highest weight (0.5) due to its indication of maturity and validation within the field. Documented limitations received a moderate weight (0.3), acknowledging the importance of critical evaluation. Empirical benchmarks were assigned a lower weight (0.2) in recognition of the limited availability of data specific to social work applications. The results of this multi-criteria analysis are summarized in Table 2. To further illustrate the trade-off between security performance and implementation complexity, Figure 3 provides a visual comparison of the evaluated technical solutions.

Table 2. Analysis of IoT Technical Solutions

Technical Solution | Security | Performance Impact | Implementation Complexity | Cost | Applicable Scenarios |

Blockchain Technology | 9.2 | 6.5 | 7.5 | 7.0 | Data Integrity Verification |

Homomorphic Encryption | 9.8 | 4.2 | 9.0 | 8.5 | Encrypted Computation |

Federated Learning | 8.5 | 7.8 | 8.0 | 6.0 | Privacy-Preserving Training |

Differential Privacy | 8.0 | 8.5 | 6.5 | 5.5 | Statistical Privacy |

Zero-Knowledge Proof | 9.5 | 5.8 | 8.8 | 8.0 | Identity Authentication |

Secure Multi-Party Computation | 9.3 | 6.2 | 8.5 | 7.5 | Multi-Party Collaboration |

Figure 3. Technical Solution Performance-Complexity Analysis Chart

- In-Depth Technical Solution Analysis with Implications for Social Work Applications

- Homomorphic Encryption

Homomorphic encryption exhibits exceptional security performance, scoring 9.8 out of 10, by enabling computations on encrypted data without requiring decryption. This feature renders it particularly suitable for social work contexts that demand stringent protection of sensitive information, such as mental health records, histories of abuse, or family circumstances [83],[85][86]. However, significant limitations warrant explicit consideration. Homomorphic encryption demonstrates the highest implementation complexity (9.0/10) and imposes substantial computational overhead, markedly increasing system performance requirements. For social service organizations with limited IT infrastructure, this represents a considerable technical barrier. Current implementations incur performance overheads ranging from 100 to 1000 times that of unencrypted computations, rendering real-time processing of large datasets impractical [87]-[90]. Social Work Applicability: This technology is best suited for periodic batch processing of highly sensitive aggregated data — for example, annual statistical reporting on service outcomes — rather than real-time service delivery systems.

- Zero-Knowledge Proof Technology

Zero-knowledge proofs achieve highly effective authentication, with a security score of 9.5, by enabling identity verification without disclosing underlying identifying information. This characteristic is especially advantageous in social service environments that require preservation of user identity privacy while ensuring accountability of service providers. Limitations include relatively high implementation complexity (8.8/10) and the necessity for specialized cryptographic expertise, which restricts accessibility primarily to large, well-resourced organizations. Additionally, emerging threats from quantum computing may compromise certain zero-knowledge proof schemes, necessitating ongoing cryptographic updates [91]-[95]. Social Work Applicability: Recommended for secure portal access by vulnerable service users and professionals, facilitating strong authentication without the need to store sensitive biometric identifiers.

- Federated Learning Technology

Federated learning offers significant advantages for privacy-preserving collaborative machine learning, achieving a security score of 8.5 by enabling model training across multiple institutions without exchanging raw data. This approach is particularly relevant for data collaboration and analysis among multiple social service agencies. Its implementation complexity is moderate (8.0/10), and it incurs relatively low costs (6.0/10), enhancing feasibility for deployment within resource-constrained social work sectors [96]-[104]. A novel consideration for social work is the explicit incorporation of ethical fairness constraints to prevent algorithmic bias against vulnerable populations. Models trained on federated data from multiple agencies may inadvertently amplify historical discrimination present in individual organizational datasets. Social Work Applicability: Highly recommended for multi-agency collaboration (e.g., child protective services, health, and education integration), enabling protective intelligence sharing while preserving individual client confidentiality.

- Blockchain Technology

Blockchain technology effectively ensures data integrity verification, with a score of 9.2, by preventing tampering and forgery. This capability is critical for child protection records, court-related documentation, and treatment compliance verification, where data authenticity holds legal and therapeutic significance [105]. However, blockchain is characterized by high energy consumption and comparatively slow transaction speeds (e.g., Bitcoin processes approximately 7 transactions per second versus Visa’s 65,000 transactions per second), posing scalability challenges for large-scale, real-time IoT deployments. For social work applications involving real-time care coordination, blockchain transaction latency may introduce unacceptable delays [84],[106]-[116]. Emerging solutions such as lightweight consensus mechanisms (e.g., Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance) and sharding techniques show promise for IoT contexts [117], although research specific to social work applications remains limited. Social Work Applicability: Suitable for non-urgent, high-value records requiring immutable audit trails (e.g., consent documentation, incident reports) rather than for real-time monitoring systems.

- Differential Privacy

Differential privacy technology offers theoretical advantages in statistical privacy protection, scoring 8.0, with relatively low implementation complexity (6.5/10) and moderate costs (5.5/10), thereby enhancing its feasibility for mainstream adoption. A persistent challenge lies in achieving an optimal balance between privacy budget allocation and data utility. Excessive consumption of the privacy budget diminishes analytical usefulness, whereas insufficient allocation risks privacy violations. This trade-off is particularly salient for social workers conducting needs assessments or outcome evaluations [118]-[123]. Social Work Applicability: Recommended for program evaluation and aggregate demographic reporting where individual-level accuracy is less critical than population-level insights.

- Secure Multi-Party Computation

Secure multiparty computation enables multiple parties to jointly compute results without revealing individual inputs, achieving a security score of 9.3. This facilitates inter-organizational collaboration on sensitive matters, such as identifying children at risk across agency boundaries without disclosing individual identifiers. Its implementation complexity (8.5/10) and costs (7.5/10) position it between federated learning and homomorphic encryption in terms of accessibility.

- Comparative Analysis Relative to Existing Literature

In contrast to Siddiqui and Alazzawi’s [117] generic evaluation of IoT security technologies focused on consumer IoT sectors, the present study uniquely incorporates social work-specific implementation constraints, including limited IT capacity, vulnerable user populations, and legal reporting obligations, alongside ethical considerations such as fairness, dignity, and social justice. While Johnson et al.’s prior governance framework research provided general institutional analysis, this study specifies how formal governance mechanisms (e.g., regulations) and informal institutions (e.g., ethical codes, professional norms) distinctly influence technology adoption within social work contexts.

- Synthesized Recommendations: Hybrid Technical Approaches

A key insight derived from this analysis is that no single technology constitutes a universally optimal solution. Instead, future developments should prioritize context-specific hybrid approaches that integrate multiple technologies. Exemplary Implementation Scenario: Multi-Institutional Child Protection Data Sharing

- Data Collection Phase (Resource Layer): Employ differential privacy techniques (complexity: 6.5/10; cost: 5.5/10) during initial data gathering from field social workers and institutional partners to minimize the collection of identifiable information at the outset.

- Model Training Phase (Collaborative Layer): Implement a federated learning framework (security: 8.5/10; complexity: 8.0/10) enabling multiple child protective service agencies to collaboratively train predictive risk models on local, non-shared datasets. Each agency retains data on local servers, with only model parameters exchanged.

- Data Aggregation Phase (Privacy Layer): Reapply differential privacy techniques during parameter aggregation to ensure that global model updates do not reveal outlier patterns specific to any single agency.

- Critical Record Authentication (Integrity Layer): Utilize blockchain technology (security: 9.2/10) to immutably record high-stakes decisions (e.g., removal orders, placement changes), thereby maintaining an audit trail essential for legal accountability and longitudinal child outcome tracking.

- Access Control Phase (Authentication Layer): Deploy zero-knowledge proof technology to facilitate portal access for professionals and authorized family members, enabling identity verification without storing biometric identifiers.

Cost-Benefit Projection: This hybrid approach achieves comprehensive security across multiple dimensions — including privacy, integrity, authentication, and confidentiality — while maintaining moderate average implementation complexity (mean 7.6/10) and costs (mean 6.6/10). This represents a substantially more feasible solution compared to single-technology approaches such as homomorphic encryption, which exhibits higher complexity (9.0/10) and cost (8.5/10).

- Analysis of Governance Framework Components

Effective governance of the IoT necessitates systematic consideration of six core components: regulatory compliance, technical standards, ethical guidelines, risk management, data management, and incident response. Each component exhibits unique attributes concerning its significance, implementation complexity, scope of applicability, and frequency of updates [124].

- Detailed Assessment of Governance Framework Components

Table 3 presents a comprehensive evaluation of these governance components. The importance scores are derived from weighted metrics that reflect the prevalence and mandatory nature of provisions within key regulatory instruments — such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), and the UK Product Security and Telecommunications Infrastructure Act 2022 — as well as relevant standards like ETSI EN 303 645 and professional codes of ethics in social work. Implementation difficulty scores are based on the frequency and severity of documented challenges, including financial costs, technical complexity, interdepartmental coordination, and cultural resistance.

Table 3. Governance Framework Components Analysis

Governance Framework Component | Importance Score | Implementation Difficulty | Coverage Scope | Update Frequency |

Regulatory Compliance | 9.5 | 7.5 | Comprehensive | Annually |

Technical Standards | 8.8 | 6.8 | Technical Layer | Continuously |

Ethical Guidelines | 9.2 | 8.2 | Comprehensive | Annually |

Risk Management | 9.0 | 7.0 | Comprehensive | Quarterly |

Data Management | 8.7 | 6.5 | Data Layer | Continuously |

Incident Response | 8.5 | 6.0 | Operational Layer | Real-time |

- In-Depth Examination of Critical Components

- Regulatory Compliance: Foundational Element or Illusory Assurance?

Regulatory compliance is widely regarded as the foundational pillar of governance frameworks, receiving the highest importance rating (9.5 out of 10). It primarily involves adherence to legal mandates such as GDPR, personal data protection laws, and health-related regulations analogous to HIPAA [125]-[127]. However, a critical paradox emerges: despite its paramount importance, regulatory compliance typically follows an annual update cycle, which lags significantly behind the rapid evolution of technical standards and the continuously emerging threat landscape. This temporal discrepancy engenders a “compliance trap,” wherein social service organizations may achieve formal regulatory compliance while deploying technologies that harbor novel vulnerabilities not yet encompassed by existing regulatory frameworks [17],[128]-[130].

For instance, GDPR requirements finalized in 2018 emphasize transparency in data collection and processing, as well as the protection of individual rights. Nevertheless, advanced technologies developed subsequently — such as homomorphic encryption, which enables computation on encrypted data, and federated learning, which facilitates distributed model training — introduce capabilities that create regulatory gaps. These gaps allow technically compliant implementations to potentially facilitate new forms of privacy violations unforeseen by current regulations. In social work contexts, this challenge is further complicated by the involvement of dependent individuals (e.g., children or clients under court orders), whose data processing may be legally justified by protective mandates. This situation generates tension between regulatory privacy frameworks and professional obligations to safeguard vulnerable populations.

- Ethical Guidelines: Translating Principles into Practice

Ethical guidelines hold particular prominence within social work, receiving a high importance rating (9.2 out of 10) due to their emphasis on foundational values such as human dignity, social justice, and non-maleficence [131]-[138]. Nonetheless, the translation of these abstract ethical principles into practical implementation poses significant challenges, as reflected by the highest implementation difficulty rating among all components (8.2 out of 10). This difficulty underscores the fundamental challenge of operationalizing ethical concepts into concrete technical specifications. The literature on value-sensitive design attempts to bridge this gap; however, the operationalization of principles such as “do no harm” into measurable fairness metrics within federated learning algorithms or the development of equitable privacy budget allocation strategies for differential privacy remains underdeveloped theoretically [139]-[143]. Specific ethical-technical tensions in social work IoT applications include:

- Confidentiality versus Child Safety: Home monitoring systems for at-risk children must balance respect for privacy with the need for welfare surveillance. Determining the threshold of behavioral anomalies that should trigger automated intervention alerts remains unresolved.

- Autonomy versus Vulnerability: The rights of elderly or cognitively impaired individuals to make independent decisions may conflict with paternalistic protective interventions enabled by monitoring technologies.

- Equity versus Stigmatization: Ensuring that vulnerable populations benefit from IoT applications without fostering a “surveillance society” that disproportionately targets marginalized groups.

These tensions lack definitive technical solutions and necessitate ongoing ethical deliberation within multidisciplinary teams.

- Technical Standards: The Challenge of Innovation Outpacing Standardization

Technical standards play a crucial role in ensuring the security of IoT devices, with an importance rating of 8.8 out of 10. International security standards such as ETSI EN 303 645 and IEC 62443 have been established for consumer IoT devices. However, a significant limitation is that these standards address general IoT contexts and do not adequately account for the specific requirements of social work applications [144]-[151]. Notably absent are standards pertaining to:

- Data sensitivity classification schemes tailored to social work contexts

- Authentication mechanisms designed to accommodate users with cognitive or sensory disabilities

- Protocols for detecting fairness and bias in algorithmic decision-making related to child protection or care allocation

- Privacy-preserving techniques compatible with mandatory reporting obligations

- Requirements for a Dynamic Governance Model

The foregoing analysis indicates that governance frameworks cannot remain static or solely compliance-driven. Instead, effective governance must be inherently dynamic and adaptive, incorporating the following elements [152]-[161]:

- Rapid Feedback Mechanisms: Implementing quarterly risk management reviews, as opposed to relying solely on annual regulatory updates, to facilitate timely identification of emerging vulnerabilities.

- Standing Ethics Committee: Establishing a multidisciplinary committee comprising technical experts, social workers, legal professionals, disability rights advocates, and service recipients to address ethical and social risks arising from emerging technologies not yet covered by existing regulations.

- Continuous Standards Development: Accelerating the development of standards that address social work-specific IoT requirements, potentially through participatory standard-setting processes involving practitioners.

- Scenario Planning: Proactively identifying and assessing the governance implications of emerging technological combinations — such as federated learning, differential privacy, and blockchain — prior to their deployment.

- Research Limitations and Theoretical Contributions

- Study Limitations

This investigation acknowledges several constraints that inherently affect the generalizability of its findings:

- Limitation 1: Emerging Research Domain: The integration of IoT technologies within social work is an emergent field, characterized by a relatively limited corpus of empirical studies compared to broader IoT or healthcare informatics research. Although the 55 studies included herein represent a comprehensive survey of extant literature, this limited volume may restrict the empirical robustness of the conclusions drawn. This limitation is partially addressed through a hybrid qualitative-quantitative synthesis approach, which combines textual evidence with explicit scoring methodologies.

- Limitation 2: Regulatory and Cultural Heterogeneity: Governance frameworks and contexts for IoT implementation vary considerably across different countries and regions. For instance, European contexts governed by the GDPR differ markedly from United States environments regulated under the HIPAA, as well as from social protection systems in the Global South. The framework proposed in this study emphasizes generic principles; however, users are advised to adapt its components to align with specific regulatory and cultural settings.

- Limitation 3: Risk of Temporal Obsolescence: Given the rapid pace of technological advancement, some conclusions — particularly those related to technical solution rankings and standards recommendations — may become outdated within two to three years. This necessitates planned updates to the research and ongoing surveillance of emerging technologies.

- Limitation 4: Language Scope: The search strategy prioritized publications in English and Chinese, potentially underrepresenting relevant research published in Spanish, Portuguese, or other languages. This limitation may restrict the inclusion of insights from social work contexts in the Global South.

- Quantitative Gap Analysis Results

Table 4 presents a systematic identification and prioritization of research gaps. The gap scoring methodology is defined as follows:

The Current Research Level ( ) is calculated by the formula:

) is calculated by the formula:

|

| (4) |

where  denotes the number of publications within a specific research domain,

denotes the number of publications within a specific research domain,  is a research maturity index on a scale from 1 to 5 reflecting the proportion of empirical studies, reviews, and theoretical frameworks, and

is a research maturity index on a scale from 1 to 5 reflecting the proportion of empirical studies, reviews, and theoretical frameworks, and  ,

,  are standardization coefficients used to normalize these components.

are standardization coefficients used to normalize these components.

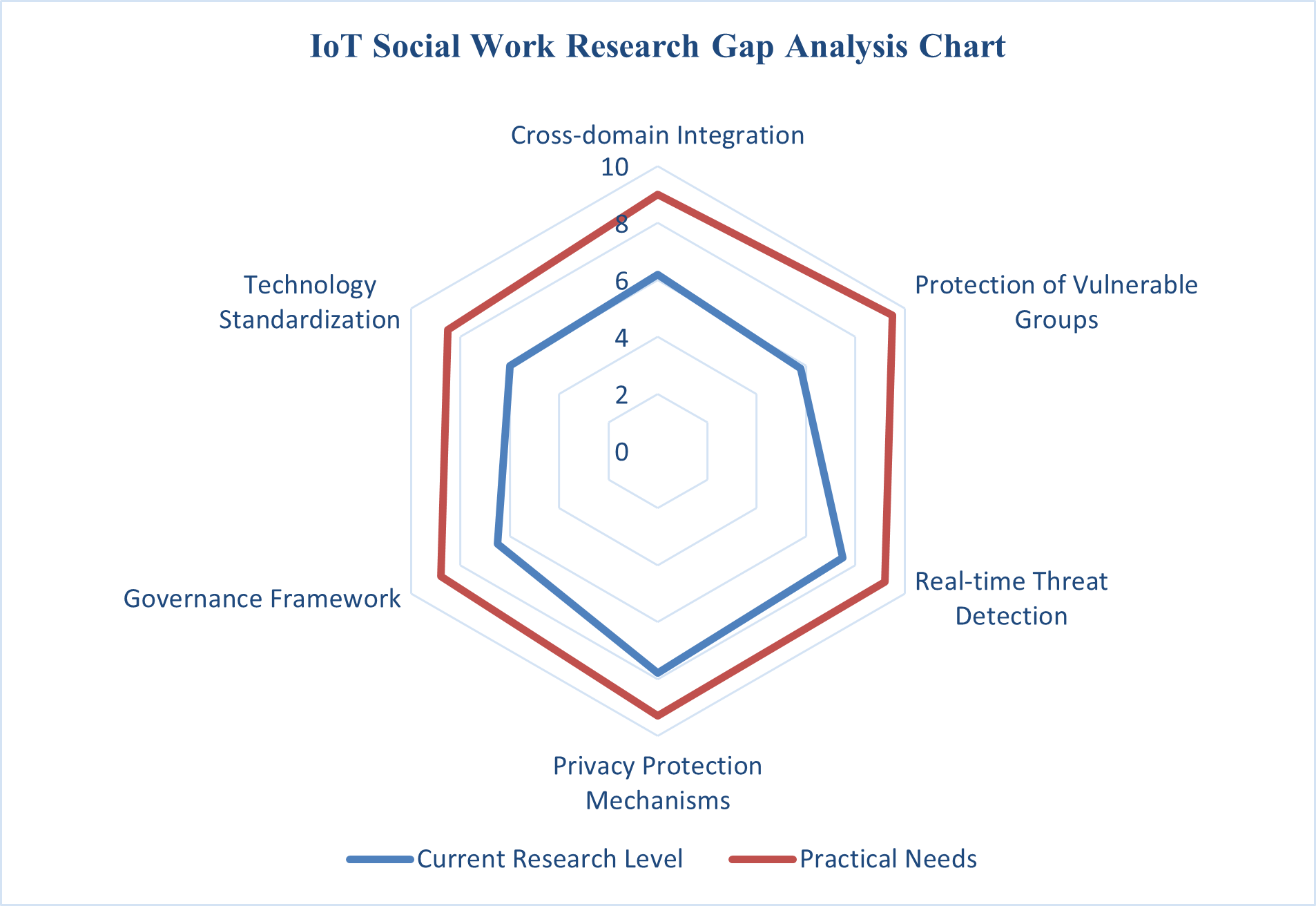

Table 4. Analysis of Research Gaps

Research Area | Current Research Level | Practical Needs | Research Gap | Priority Level |

Cross-domain Integration | 6.2 | 9.0 | 2.8 | High |

Protection of Vulnerable Groups | 5.8 | 9.5 | 3.7 | Very High |

Real-time Threat Detection | 7.5 | 9.2 | 1.7 | Medium |

Privacy Protection Mechanisms | 7.8 | 9.3 | 1.5 | Medium |

Governance Framework | 6.5 | 8.8 | 2.3 | High |

Technology Standardization | 6.0 | 8.5 | 2.5 | Medium |

The Practical Needs ( ) metric, ranging from 1 to 10, is derived through content analysis of social work organizational reports, policy documents, and literature references to “future challenges” or “practical difficulties.” The Research Gap (

) metric, ranging from 1 to 10, is derived through content analysis of social work organizational reports, policy documents, and literature references to “future challenges” or “practical difficulties.” The Research Gap ( ) is then computed as:

) is then computed as:

|

| (5) |

Priority levels are classified as Medium ( < 2.0), High (2.0 ≤

< 2.0), High (2.0 ≤  < 3.0), and Very High (

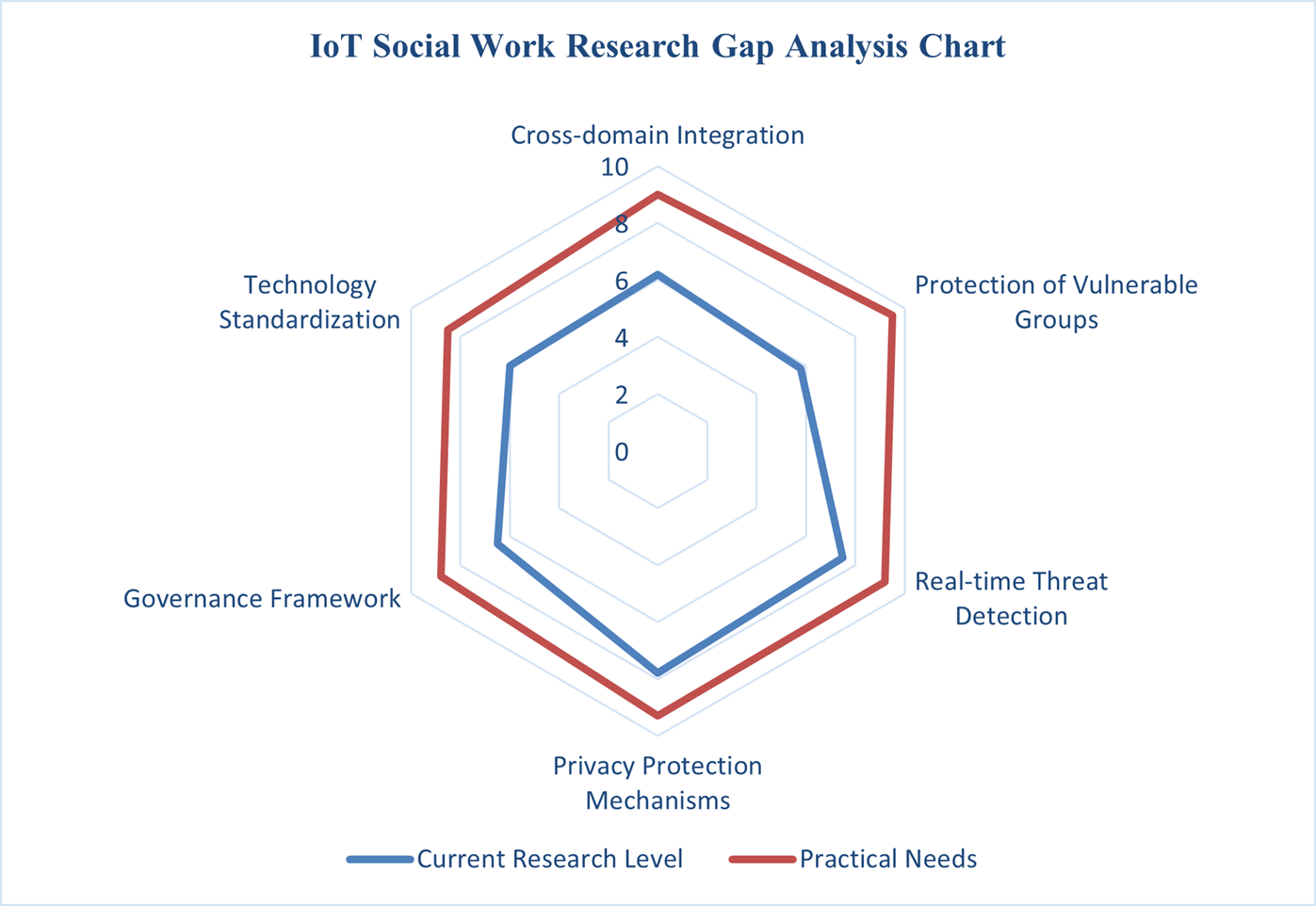

< 3.0), and Very High ( ≥ 3.0). Interpretation of the gap analysis reveals a pronounced disparity between academic research focus and practical organizational needs across six research domains. Notably, the domain of “Protection of Vulnerable Groups” exhibits the largest gap score (3.7), indicating a significant deficiency in research despite urgent practical demand. This finding substantiates the prioritization recommendations outlined in subsequent sections. These research gaps are visually summarized in the chart presented in Figure 4.

≥ 3.0). Interpretation of the gap analysis reveals a pronounced disparity between academic research focus and practical organizational needs across six research domains. Notably, the domain of “Protection of Vulnerable Groups” exhibits the largest gap score (3.7), indicating a significant deficiency in research despite urgent practical demand. This finding substantiates the prioritization recommendations outlined in subsequent sections. These research gaps are visually summarized in the chart presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4. IoT Social Work Research Gap Analysis Chart

- Theoretical Contributions

Despite the aforementioned limitations, this study advances the field through several key theoretical contributions:

- Contribution 1: Inaugural Systematic Interdisciplinary Framework: This work constitutes the first systematic effort to develop a multidimensional analytical framework specifically designed to evaluate IoT security and privacy risks, technologies, and governance within the context of social work. The framework bridges a critical interdisciplinary gap by integrating engineering and social science perspectives, which have previously been addressed in isolation.

- Contribution 2: Transparent Quantitative Synthesis Methodology: By explicitly detailing the quantitative assessment algorithms (Formula (1) to Formula (5)), the rationale for weighting, and the scoring procedures, this study offers a replicable methodological approach for future research endeavors. This transparency facilitates:

- Reproduction of analyses with updated literature

- Adaptation of methodologies to other professional domains such as nursing and education

- Meta-evaluations assessing the robustness of the methodology

- Critical scrutiny and methodological refinement

- Contribution 3: Social Work-Specific Risk Taxonomy: Rather than employing generic cybersecurity risk frameworks, this study develops a taxonomy tailored to the unique characteristics of social work. This taxonomy accounts for factors such as dependent service users, mandatory reporting obligations, the dual imperatives of autonomy and safety, and the heightened risks of stigma.

- Practical Implications and Contextualized Recommendations

- Recommendations for Social Service Organizations

Social service organizations are advised to systematically enhance their cybersecurity posture by implementing the following measures:

- Comprehensive Cybersecurity Management Systems: Appoint a dedicated cybersecurity officer with direct reporting lines to executive leadership. Conduct quarterly risk assessments utilizing the framework outlined in Table 1 and Figure 2. Develop and enforce configuration management protocols for device firmware updates, addressing the critical deficiencies identified in Figure 2.

- Workforce Cybersecurity Awareness: Mandate annual cybersecurity training for all personnel, emphasizing password hygiene, phishing detection, and incident reporting procedures. Provide specialized training for staff managing high-risk systems, such as mental health monitoring and child protection databases. Additionally, implement digital literacy programs for service users to enhance their capacity for informed consent.

- Technology Selection Criteria: Favor contextually tailored combinations of security technologies, as discussed in Section 3.2.4, rather than relying on singular solutions. Require vendors to demonstrate compliance with ETSI EN 303 645 standards at a minimum, supplemented by privacy assessments specific to social work contexts. Prioritize technologies with lower implementation complexity (rated between 6.0 and 7.0) to accommodate organizational capacity constraints.

- Vulnerability Management: Establish mechanisms to ensure timely firmware updates, potentially leveraging federated learning approaches to coordinate updates across multiple organizations. Conduct annual penetration testing of critical systems. Maintain incident response protocols with clearly defined escalation pathways to senior management and legal counsel.

- Recommendations for Policymakers

Policymakers should consider the following actions:

- Accelerated Standards Development: Commission the creation of social work-specific IoT security standards that address critical gaps identified in this study, including disability-accessible authentication methods, fairness assessment protocols for algorithmic decision-making in child protection and care allocation, privacy-preserving techniques compatible with mandatory reporting obligations, and vulnerability disclosure procedures suitable for resource-constrained organizations [124]. Foster government-industry-academia partnerships to facilitate participatory standard-setting processes that meaningfully incorporate social work expertise, moving beyond treating social work as a passive regulatory compliance domain. Transition from annual regulatory updates to quarterly governance review cycles to maintain alignment with evolving technical standards and threat landscapes.

- Regulatory Clarification and Enhancement: Develop explicit guidance regarding the regulatory status of emerging technologies under existing frameworks such as GDPR and HIPAA equivalents. Clarify the implications of federated learning, differential privacy, homomorphic encryption, and zero-knowledge proofs, specifying whether these constitute additional safeguards or introduce novel compliance obligations. Establish clear legal frameworks to reconcile tensions between privacy regulations and mandatory reporting requirements — for example, determining whether differential privacy techniques that reduce data precision still satisfy child protection reporting thresholds. Institute breach notification requirements tailored to social work, including protocols for psychological harm assessment and victim support when data concerning vulnerable populations is compromised. Introduce safe harbor provisions for social service organizations that implement good-faith security measures in accordance with recommended frameworks, thereby mitigating litigation risks and encouraging proactive adoption [162].

- Resource Allocation and Implementation Support: Provide targeted funding for digital infrastructure upgrades within social service organizations, recognizing that private-sector cost-sharing models are unsuitable for non-profit entities. Support workforce development through scholarships, certification programs, and knowledge-sharing networks to build internal cybersecurity expertise. Develop shared security infrastructures, such as government-supported secure cloud platforms incorporating federated learning and encrypted data repositories, to reduce individual implementation costs via economies of scale.

- Recommendations for Technology Developers

Technology developers are encouraged to:

- Integrate Social Work-Specific Design Requirements: Engage in participatory design processes that include social workers, service users, disability advocates, and family members from the outset, ensuring that technical designs reflect lived experiences, ethical considerations, and practical constraints. Incorporate accessibility-by-design principles to accommodate users with cognitive, sensory, or motor disabilities, addressing both ethical imperatives and practical necessities. Apply value-sensitive design frameworks to systematically translate social work ethical principles — such as dignity, justice, and non-maleficence — into technical specifications and design constraints, advancing beyond generic privacy-by-design approaches [163].

- Enhance Device Security and Manageability: Commit to eliminating default credentials by requiring unique credential creation during device initialization prior to deployment. Implement secure firmware update mechanisms that support over-the-air updates with cryptographic integrity verification and rollback capabilities, thereby addressing the firmware update deficiencies identified in Section 3.1.C. Provide transparent, accessible security documentation that includes non-technical summaries of device security features, update procedures, and known limitations, tailored for social workers and administrators.

- Promote Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Establish enduring partnerships with social work educational institutions and practitioner organizations to create feedback loops that ensure ongoing alignment between technological development and professional practice. Support open standards and interoperability to prevent vendor lock-in and maintain technological flexibility for social work organizations. Contribute resources and personnel to collaborative government-industry-academia initiatives focused on social work IoT standards development, recognizing this as a strategic investment in long-term market legitimacy.

- Directions for Future Research

Figure 4 presents a radar chart delineating research gaps in IoT applications within social work, thereby providing a data-driven agenda for future scholarly inquiry.

- Primary Priority: Protection of Vulnerable Groups

This domain exhibits the highest research gap score (3.7), reflecting a significant deficiency in targeted academic solutions despite urgent practical needs. Future research should focus on:

- Developing Adaptive Protection Mechanisms: Advance beyond generic security models by creating context-specific technologies that accommodate the unique characteristics of vulnerable populations. Research areas include cognitive accessibility in security design — such as the functionality of multi-factor authentication for individuals with cognitive disabilities — and equity-aware fairness constraints for algorithmic decision-making in child protection IoT systems. Investigate trauma-informed technology design that balances necessary protection with the avoidance of re-traumatization, recognizing that surveillance-like monitoring can trigger adverse responses. Explore the integration of digital literacy support within IoT systems to embed protection mechanisms that require minimal user security expertise.

- Employing Participatory Design Methodologies: Actively involve vulnerable populations — including children (with age-appropriate methods), individuals with disabilities, elderly service users, and family members — in design and evaluation processes. This approach transcends traditional accessibility compliance by embedding lived expertise throughout development. Particular attention should be given to managing representation and power dynamics to ensure that research findings authentically reflect participants’ priorities rather than researcher assumptions. Conduct longitudinal implementation studies spanning two or more years to assess technology deployment effects on vulnerable populations, measuring both security outcomes and unintended consequences such as surveillance anxiety, autonomy reduction, and widening digital divides [125],[164][165].

- Secondary Priorities: Cross-Domain Integration and Governance Frameworks

These areas demonstrate substantial research gaps (2.8 and 2.3, respectively). Future investigations should address:

- Cross-Domain Integration Research: Move beyond disciplinary silos to establish integrated research platforms synthesizing perspectives from information engineering, social work, law, ethics, and organizational management. Key research questions include formalizing social work ethical principles — such as dignity, social justice, and non-maleficence — into computable constraints within federated learning, differential privacy, and related technical systems. Evaluate the operationalization of established value-sensitive design frameworks in practice [163]. Examine multi-agency data governance models that comply with legal mandates while maintaining technical feasibility and ethical appropriateness, including privacy-by-design specifications for child protective services data sharing. Investigate participatory standard-setting processes that meaningfully integrate social work expertise alongside technical expertise to develop standards that address genuine professional needs rather than generic compliance.

- Governance Framework Localization: Conduct comparative analyses of IoT governance approaches across regions, such as GDPR-regulated Europe, HIPAA-influenced United States, and emerging South Asian social protection contexts, identifying transferable principles and context-specific requirements. Develop realistic organizational readiness assessments to evaluate social service organizations’ capacity to implement governance frameworks, including feasible timelines and resource needs based on organizational size and IT maturity. Explore governance adaptations suitable for underfunded social service organizations in low-resource settings, identifying minimal viable frameworks that provide meaningful protection while remaining implementable.

- Tertiary Research Priorities

Additional important research areas warranting attention include:

- Real-Time Threat Detection (Gap: 1.7): Although existing scholarship addresses this area, specific applications within social work remain underdeveloped. Research should investigate behavioral anomaly detection tailored to social work IoT contexts, differentiating “normal” device behavior across child protection monitoring, mental health support, and elderly care systems, while minimizing false positives that could trigger unwarranted interventions. Examine supply chain security challenges faced by social work organizations lacking procurement expertise, and develop mechanisms for supply chain transparency and device verification [166].

- Privacy Protection Mechanisms (Gap: 1.5): Adapt emerging privacy-preserving techniques to social work contexts, including federated learning models that accommodate mandatory reporting obligations requiring individual-level data access. Investigate enforcement of fairness constraints across federated nodes. Explore methods for conducting privacy-preserving outcome evaluations — such as cost-per-outcome, client satisfaction, and service quality metrics — on encrypted or federated data without compromising analytical rigor.

- Technology Standardization (Gap: 2.5): Prioritize rapid development of social work-specific technical standards within 12 to 24 months, contrasting with traditional multi-year cycles. Develop meaningful IoT security certification schemes that complement ETSI EN 303 645 standards and specifically address social work vulnerabilities and ethical considerations, enabling organizations to identify compliant solutions.

- Methodological Recommendations for Future Research

Future research endeavors should:

- Employ mixed-methods designs that integrate quantitative security assessments with qualitative phenomenological studies exploring service users’ experiences of technology-enabled protection or surveillance.

- Conduct pilot implementation studies involving at least two to three social work organizations to evaluate proposed frameworks in real-world settings, documenting implementation challenges and necessary adaptations prior to broader scaling.

- Establish longitudinal tracking studies spanning multiple years to measure security outcomes, organizational transformations, and service recipient experiences, acknowledging that the effects of IoT governance manifest gradually.

- Facilitate iterative theory development through successive refinement as empirical evidence accumulates, recognizing that IoT applications in social work constitute an emergent domain requiring dynamic theoretical frameworks rather than static hypothesis testing.

- CONCLUSION

This systematic literature review introduces an innovative, multidimensional framework designed to address the complex cybersecurity and privacy challenges associated with the integration of IoT technologies within the field of social work. Distinct from the generalized application of frameworks derived from healthcare or smart city contexts, this study develops a tailored analytical perspective specific to social work by synthesizing technical, governance, and ethical considerations. The principal findings and their implications are elaborated below.

A key contribution of this research lies in delineating the threat landscape unique to social work. The analysis indicates that the predominant risks are not primarily attributable to advanced cyberattacks but rather to systemic infrastructural vulnerabilities. More than 60% of the reviewed studies highlight the widespread use of consumer-grade IoT devices characterized by “insecure-by-design” features — such as default passwords, unencrypted data transmission, and absence of firmware update capabilities — within critical professional settings. This insight shifts the focus of mitigation efforts from complex attack methodologies toward fundamental security practices. Additionally, the study proposes a social work-specific risk taxonomy that incorporates contextual variables, including service users’ limited digital literacy and reduced capacity to provide informed consent. These factors elevate privacy risk assessments in domains such as mental health services to a “Very High” category (Privacy Risk Score > 8.0). This vulnerability, rooted in the socio-economic and cognitive characteristics of the client population, represents a distinctive aspect of the social work environment.

In the evaluation of technical interventions, the findings caution against a uniform, “one-size-fits-all” strategy, advocating instead for a context-sensitive, hybrid approach. Although homomorphic encryption offers the highest level of security (rated 9.8/10), its considerable implementation complexity (9.0/10) limits its practicality for social service organizations with constrained resources. In contrast, federated learning emerges as a more balanced alternative, delivering robust privacy protection (8.5/10) alongside manageable implementation complexity (8.0/10), rendering it particularly appropriate for multi-agency collaborations. This analysis provides pragmatic guidance for organizations, emphasizing that optimal security outcomes — encompassing confidentiality, integrity, and availability — are best achieved through the integration of complementary technologies within feasible operational parameters.

The study further critically assesses governance frameworks, uncovering a paradox wherein formal regulatory compliance, typically characterized by slow, annual update cycles, fails to adequately safeguard against the rapid evolution of technological threats. The greatest challenge identified is not the adherence to technical standards but the translation of abstract ethical principles (rated 9.2/10 in importance) into concrete organizational policies and technical specifications. This finding underscores the imperative for governance mechanisms to be dynamic and adaptive rather than static and compliance-driven. To address this, the study advocates for the establishment of permanent, multi-stakeholder ethics committees — including technologists, social workers, legal experts, and service users — as a vital mechanism for navigating emergent ethical challenges.

Methodologically, this research contributes in two significant ways. First, it introduces a transparent and replicable quantitative assessment framework that facilitates critical evaluation of both technological solutions and governance models. Second, it pioneers a novel algorithm for systematically quantifying research gaps, thereby providing a data-driven foundation for prioritizing future scholarly inquiry. The analysis identifies the protection of vulnerable populations as the most pressing research gap (gap score: 3.7/10), warranting immediate academic attention.

The implications of this study are threefold, offering actionable recommendations for principal stakeholders. For social service organizations, it is advised to establish dedicated cybersecurity roles, conduct regular risk assessments, and prioritize technologies with moderate implementation complexity. Policymakers are encouraged to develop IoT security standards tailored specifically to social work, provide “safe harbor” provisions to incentivize responsible technology adoption, and allocate resources toward digital infrastructure and workforce development. For technology developers, the study calls for a paradigm shift toward participatory design and “ethics-by-design” approaches, embedding security and accessibility considerations from the outset in collaboration with social work professionals and their clients.

In conclusion, the responsible integration of IoT technologies within social work transcends a mere technical challenge, constituting an ethical imperative intimately connected to the profession’s foundational mission of promoting social justice and safeguarding vulnerable populations. This study offers a foundational framework and delineates a clear research agenda to support this endeavor. It advocates for sustained, collaborative engagement among researchers, practitioners, policymakers, and technology developers to ensure that technological advancements uphold, rather than undermine, the fundamental rights and dignity of all individuals.

REFERENCES

- K. Hjelm and L. Hedlund, “Internet-of-Things (IoT) in healthcare and social services – experiences of a sensor system for notifications of deviant behaviours in the home from the users’ perspective,” Health Informatics Journal, vol. 28, no. 1, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1177/14604582221075562.

- H. Wan and K. Chin, “Exploring internet of healthcare things for establishing an integrated care link system in the healthcare industry,” International Journal of Engineering Business Management, vol. 13, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1177/18479790211019526.

- L.-P. Hung, N.-C. Hsieh, L.-J. Lin, and Z.-J. Wu, “Using Internet of things technology to construct an integrated intelligent sensing environment for long-term care service,” International Journal of Distributed Sensor Networks, vol. 17, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1177/15501477211059392.

- Liyakathunisa, A. Alsaeedi, S. Jabeen, and H. Kolivand, “Ambient Assisted Living Framework for Elderly Care Using Internet of Medical Things, Smart Sensors, and GRU Deep Learning Techniques,” Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Smart Environments, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 5-23, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3233/AIS-210162.

- P. Kourtesis, “A Comprehensive Review of Multimodal XR Applications, Risks, and Ethical Challenges in the Metaverse,” Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, vol. 8, no. 11, p. 98, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/mti8110098.

- M. Adil, H. Song, S. Mastorakis, H. Abulkasim, A. Farouk, and Z. Jin, “UAV-Assisted IoT Applications, Cybersecurity Threats, AI-Enabled Solutions, Open Challenges With Future Research Directions,” IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 4583-4605, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/TIV.2023.3309548.

- V. Bentotahewa, M. Yousif, C. Hewage, L. Nawaf, and J. Williams, “Privacy and Security Challenges and Opportunities for IoT Technologies During and Beyond COVID-19,” in Privacy, Security And Forensics in The Internet of Things (IoT), pp. 51-76, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91218-5_3.

- M. V. K. Reddy, P. Chithaluru, P. Narsimhulu, and M. Kumar, “Security, privacy, and trust management of IoT and machine learning-based smart healthcare systems,” Advances in Computers, vol. 137, pp. 141-174, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.adcom.2024.06.006.

- A. Ullah, M. Azeem, H. Ashraf, A. A. Alaboudi, M. Humayun, and N. Jhanjhi, “Secure Healthcare Data Aggregation and Transmission in IoT — A Survey,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 16849-16865, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3052850.

- S. Datta Burton, L. M. Tanczer, S. Vasudevan, S. Hailes, and M. Carr, “The UK code of practice for consumer IoT cybersecurity: where we are and what next,” The PETRAS National Centre of Excellence for IoT Systems Cybersecurity, 2022, https://doi.org/10.14324/000.rp.10117734.

- L. Das, D. Singh, S. Vats, K. Taliyan, D. Bhargava, and D. Bhatnagar, “Smart Healthcare in Improving the Quality of Life: Revolutionizing with Application of IoT and Block Chain Technology,” in 2024 International Conference on Communication, Computer Sciences and Engineering (IC3SE), pp. 1-7, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/IC3SE62002.2024.10593009.

- T. Poleto, T. C. C. Nepomuceno, V. D. H. de Carvalho, L. C. B. d. O. Friaes, R. C. P. de Oliveira, and C. J. J. Figueiredo, “Information Security Applications in Smart Cities: A Bibliometric Analysis of Emerging Research,” Future Internet, vol. 15, no. 12, p. 393, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/fi15120393.

- H. Lee, Y. Park, H. Kim, N. Kang, G. Oh, I. Jang, and E. Lee, “Discrepancies in Demand of Internet of Things Services Among Older People and People With Disabilities, Their Caregivers, and Health Care Providers: Face-to-Face Survey Study,” Journal of Medical Internet Research, vol. 22, no. 4, p. e16614, 2020, https://doi.org/10.2196/16614.

- K. Assa-Agyei, F. Olajide, and A. Lotfi, “Security and Privacy Issues in IoT Healthcare Application for Disabled Users in Developing Economies,” Journal of Internet Technology and Secured Transactions, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 770-779, 2022, https://doi.org/10.20533/jitst.2046.3723.2022.0095.

- A. Zanella, F. Mason, P. Pluchino, G. Cisotto, V. Orso, and L. Gamberini, “Internet of things for elderly and fragile people,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.05709, 2020, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2006.05709.

- E. Blasioli and E. Hassini, “e-Health Technological Ecosystems: Advanced Solutions to Support Informal Caregivers and Vulnerable Populations During the COVID-19 Outbreak,” Telemedicine and e-Health, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 138-149, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0522.

- S. Piasecki and J. Chen, “Complying with the GDPR when vulnerable people use smart devices,” International Data Privacy Law, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 113-131, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1093/idpl/ipac001

- S. Arisdakessian, O. A. Wahab, A. Mourad, H. Otrok, and M. Guizani, “A Survey on IoT Intrusion Detection: Federated Learning, Game Theory, Social Psychology, and Explainable AI as Future Directions,” IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 4059-4092, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2022.3203249.

- M. Carr and F. Lesniewska, “Internet of Things, Cybersecurity and Governing Wicked Problems: Learning from Climate Change Governance,” International Relations, vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 391-412, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117820948247.

- M. J. Carey and M. Taylor, “The impact of interprofessional practice models on health service inequity: an integrative systematic review,” Journal of Health Organization and Management, vol. 35, pp. 682-700, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1108/JHOM-04-2020-0165.