ISSN: 2685-9572 Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro

Vol. 7, No. 4, December 2025, pp. 715-728

Exploring Teachers' Perspectives on Culturally Responsive Teaching in Stoichiometry Learning Oriented to Green Chemistry

Hajidah Salsabila Allissa Fitri 1, Antuni Wiyarsi 2, Hayuni Retno Widarti 3, Sri Yamtinah 4,

Yunilia Nur Pratiwi 5

1,2,5 Department of Chemistry Education, Yogyakarta State University, Special Region of Yogyakarta, Indonesia

3 Department of Chemistry Education, Malang State University, East Java, Indonesia

4 Department of Chemistry Education, Sebelas Maret University, Central Java, Indonesia

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 21 August 2025 Revised 10 October 2025 Accepted 28 October 2025 |

|

This study explores high school chemistry teachers’ perceptions of culturally responsive teaching (CRT) in stoichiometry learning with an orientation toward green chemistry principles. CRT provides a framework for integrating local culture, while green chemistry oriented highlights sustainability in learning abstract topics such as stoichiometry. This qualitative descriptive study involved nine Indonesian chemistry teachers selected purposively from active high school chemistry teachers familiar with stoichiometry and green chemistry. Although the sample size was limited, it provided data saturation and in-depth insights from teachers’ experiences. Data were collected through an open-ended questionnaire covering seven aspects, including teachers’ understanding of CRT, integration of local culture and green chemistry orientation in stoichiometry teaching, and perceived needs. Thematic analysis identified six themes related to teaching barriers, instructional practices, teachers’ CRT understanding, cultural integration, green chemistry orientation, and professional development needs. While teachers expressed strong support for CRT with a green chemistry orientation, implementation remains limited by structural and pedagogical constraints. The study underscores the importance of targeted support to empower teachers in fostering culturally responsive and sustainability-oriented chemistry learning, while acknowledging limitations related to the Indonesian context and the potential for social desirability bias in self-reported data. |

Keywords: Culturally Responsive Teaching; Qualitative Thematic Analysis; High School Chemistry; Green Chemistry; Indonesia |

Corresponding Author: Hajidah Salsabila Allissa Fitri, Department of Chemistry Education, Yogyakarta State University, Special Region of Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Email: hajidahsalsabila.2023@student.uny.ac.id |

This work is open access under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: H. S. A. Fitri, A. Wiyarsi, H. R. Widarti, S. Yamtinah, and Y. N. Pratiwi, “Exploring Teachers' Perspectives on Culturally Responsive Teaching in Stoichiometry Learning Oriented to Green Chemistry,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 715-728, 2025, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v7i4.14520. |

INTRODUCTION

In the 21st century, chemistry education plays a vital role in preparing students to address global challenges such as sustainability, environmental degradation, and cultural diversity [1]-[3]. It is no longer sufficient for chemistry instruction to focus solely on conceptual mastery, it must also cultivate scientific literacy [4], environmental awareness [5], and cultural competence [6] as integral outcomes of meaningful science learning. Chemistry as a discipline is deeply embedded in human life and culture, with traditional practices such as natural dyeing, fermentation, herbal medicine, and food preservation reflecting chemical principles that have been transmitted across generations [7][8]. Recognizing these cultural dimensions within chemistry learning allows students to connect science with their lived experiences [9], fostering engagement [10], relevance [11], and identity affirmation [12][13].

Despite its foundational importance, stoichiometry remains one of the most difficult topics for students to understand [14][15]. Its abstract and quantitative nature often leads to rote memorization and fragmented understanding, hindering students’ ability to apply chemical knowledge to real-world contexts [16]-[18]. Scholars have emphasized that meaningful learning in stoichiometry requires connecting symbolic representations with concrete, contextual experiences [19]. Pedagogical approaches that bridge students’ cultural backgrounds and real-life environmental issues thus offer strong potential to enhance comprehension and engagement [20].

One promising framework in this regard is Culturally Responsive Teaching (CRT), which emphasizes the integration of students’ cultural identities, values, and experiences into classroom learning [12],[21][22]. CRT encourages teachers to view diversity as a pedagogical asset [23], fostering inclusivity [24], and relevance in science education [25]. In chemistry classrooms, culturally responsive practices can make abstract concepts more tangible through examples drawn from students’ cultural contexts, such as traditional fermentation [26] or the use of plant-based natural dyes [27]. However, research suggests that teachers often struggle to apply CRT effectively due to limited conceptual understanding, insufficient training, and misconceptions that CRT is primarily applicable to the humanities rather than the sciences [28].

Parallel to CRT, the principles of green chemistry promote the design of chemical processes and products that minimize environmental harm and resource waste [29]. Integrating green chemistry into education can strengthen students’ environmental awareness [30], critical thinking [31], and sense of social responsibility [32]. Although culturally responsive teaching and green chemistry are conceptually distinct, they share a common goal of promoting relevance, responsibility, and meaningful connections between science and society [8],[33][34]. In this study, green chemistry serves as an orientation, providing an environmental and sustainability lens through which culturally responsive approaches are contextualized. For example, teaching stoichiometry through the local practice of batik-making using plant-based dyes not only demonstrates chemical reaction efficiency and waste reduction but also reinforces appreciation for cultural heritage [35][36]. This dual orientation supports the development of learners who are scientifically literate, culturally aware, and environmentally responsible.

In this context, chemical literacy refers to the ability to understand core chemical concepts, interpret chemical phenomena, and apply chemical knowledge to make informed, responsible decisions in personal, societal, and environmental contexts [37]. It encompasses not only cognitive understanding but also the ethical [38], cultural [39], and environmental dimensions of chemistry learning [31]. Meanwhile, teachers’ perspectives encompass their knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and practices related to CRT-oriented green chemistry instruction, which fundamentally shape whether and how such approaches are implemented in classrooms [40][41].

Existing literature indicates that although teachers recognize the importance of culturally relevant pedagogy [42]. Its application in chemistry, particularly in abstract topics such as stoichiometry, remains limited and lacks systematic implementation. In multicultural settings like Indonesia, teachers tend to include local examples intuitively rather than systematically within a CRT framework [43][44]. Moreover, the intersection between CRT and environmental sustainability is rarely addressed in science teaching. Preliminary research conducted by the authors confirmed these tendencies, revealing that chemistry teachers expressed strong support for integrating cultural and environmental contexts into learning, yet demonstrated limited understanding of culturally responsive teaching principles and their connection to green chemistry [24]. Many teachers perceived CRT as an optional enrichment activity rather than a foundational approach to promoting meaningful, responsible learning [45][46].

These findings reveal a significant research gap. While prior studies have explored either culturally responsive science teaching or green chemistry education independently, few have examined how teachers conceptualize the intersection of these orientations in chemistry instruction [46]. Furthermore, most existing studies emphasize student outcomes rather than teachers’ pedagogical understanding. Investigating teachers’ perspectives is thus crucial for identifying conceptual barriers, professional development needs, and opportunities to embed culturally and environmentally responsive approaches into chemistry teaching.

Accordingly, this study aims to explore high school chemistry teachers’ perspectives on implementing Culturally Responsive Teaching in stoichiometry learning oriented toward green chemistry. The term “oriented” indicates that green chemistry serves as an environmental and sustainability lens rather than a separate pedagogical framework. Specifically, the study addresses the following research questions:

- How do high school chemistry teachers understand the principles of CRT-oriented green chemistry in the context of stoichiometry learning?

- How do teachers perceive the role of green chemistry in supporting culturally responsive and sustainability-oriented instruction?

- What challenges and needs do teachers identify in implementing CRT-oriented green chemistry in their classrooms?

The research contribution of this study lies in providing empirical insights into teachers’ conceptual understandings, attitudes, and needs regarding the implementation of CRT-oriented green chemistry. By articulating these perspectives, the study contributes to the development of professional learning programs, curriculum innovations, and policy frameworks that promote chemistry teaching aligned with cultural relevance and environmental sustainability. This research thereby advances efforts to cultivate chemistry education that is contextually grounded, pedagogically inclusive, and environmentally responsible.

- METHODS

Research Design

This study employed a qualitative descriptive research type to explore high school chemistry teachers’ perceptions of Culturally Responsive Teaching (CRT) oriented green chemistry in stoichiometry learning. This research type was chosen to capture nuanced insights and provide a rich understanding of teachers’ experiences and viewpoints in a natural educational setting.

Participants and Sampling

The participants comprised nine high school chemistry teachers from different regions in Indonesia. A purposive sampling technique was used to select participants based on two main criteria: (1) actively teaching chemistry at the high school level, and (2) having experience or familiarity with stoichiometry and green chemistry concepts. This sampling strategy ensured that participants were able to provide contextually relevant perspectives aligned with the study’s focus. Although the sample size was relatively small, it was considered adequate for achieving data saturation, as recurring ideas and perspectives began to emerge after analysing the responses from the ninth participant. The small but focused sample allowed for in-depth qualitative insights, consistent with the nature of descriptive research. Moreover, two participants with a strong understanding of CRT were invited for brief follow-up interviews via online meetings to clarify and enrich the questionnaire data. This triangulation enhanced the depth and credibility of the findings.

Data Collection Instruments

Data were collected using an open-ended questionnaire distributed electronically to accommodate participants from various geographic regions. The questionnaire contained seven main aspects designed to comprehensively explore teachers’ perspectives:

- Respondents’ profile

- Barriers in teaching stoichiometry

- Instructional models and approaches used

- Teachers’ understanding of CRT

- Integration of local culture in stoichiometry instruction

- Implementation of stoichiometry learning with a green chemistry orientation

- Teachers’ needs for CRT in stoichiometry learning

Each aspect included several open-ended questions to elicit reflective and detailed responses. For example, under the integration of local culture aspect, teachers were asked, “How important do you think it is to integrate students’ cultural backgrounds into chemistry instruction, especially when teaching stoichiometry?”. The instrument was reviewed by two experts in chemistry education to ensure content validity and clarity before distribution.

Data Collection Procedure

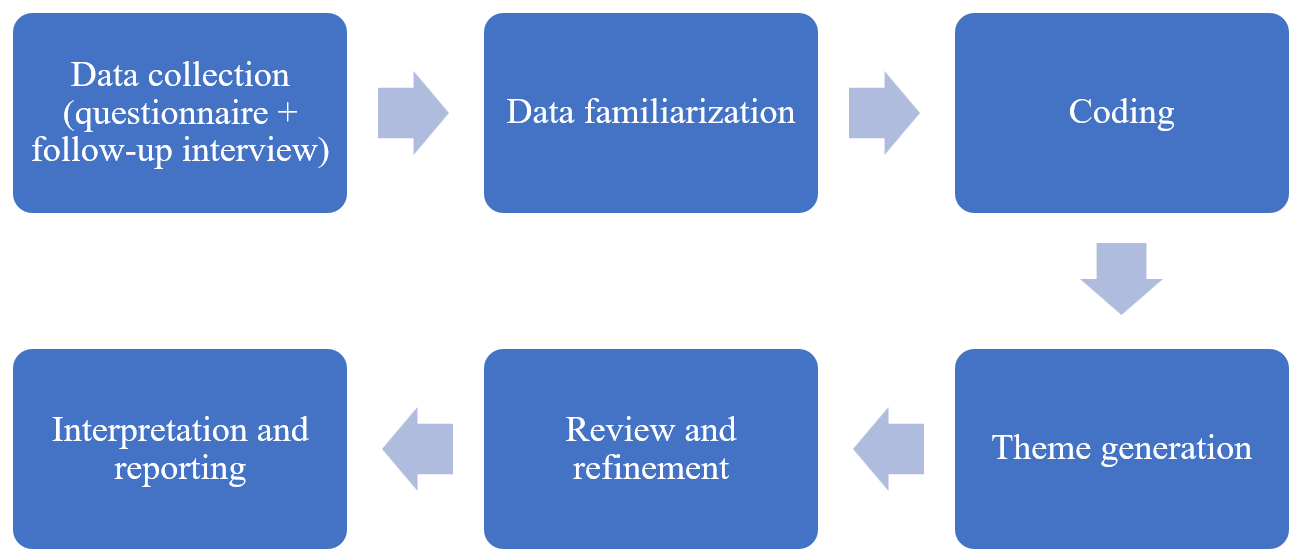

The data collection process took place over four weeks. After obtaining informed consent, participants completed the questionnaire independently. Follow-up interviews were conducted online with two teachers to gain deeper insights and verify interpretations. A flowchart summarizing the research procedure is presented in Figure 1, illustrating the sequential process from participant recruitment to thematic interpretation.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the Research Process

Data Analysis

Data analysis followed Braun and Clarke’s [47] six-phase framework for thematic analysis: (1) familiarization with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing the report. All questionnaire responses and interview transcripts were read repeatedly to identify patterns and recurring ideas. Open coding was first applied manually to capture meaningful units of information. These codes were then clustered into subcategories and broader themes. The seven questionnaire aspects served as the analytical foundation, from which four overarching themes emerged through synthesis and pattern recognition. To ensure analytical rigor, all codes were cross-checked by two researchers independently. Differences were discussed until agreement was reached, ensuring consistency and credibility in theme development.

Trustworthiness and Ethical Considerations

Several strategies were implemented to ensure the trustworthiness of the findings. Credibility was maintained through data triangulation (questionnaire and interview), peer debriefing among the research team, and expert validation of the instrument. Dependability and confirmability were supported through detailed documentation of coding decisions and an audit trail of the analytical process. Ethical considerations were rigorously addressed by obtaining informed consent from all participants, ensuring confidentiality, and emphasizing voluntary participation throughout the study. Participants were fully informed about the research purpose and procedures, and their responses were treated anonymously and confidentially.

- RESULT AND DISCUSSION

In this section, the findings of the study are presented along with an in-depth discussion that links them to relevant theories and previous research. The discussion is structured into several sub-sections to highlight key themes, interpret the data, and provide critical insights into teachers’ perspectives on Culturally Responsive Teaching (CRT) in stoichiometry learning oriented to green chemistry.

- Respondents’ Profile

This study involved nine high school chemistry teachers from diverse cultural backgrounds, including Javanese (88,9%) and Malay (11,1%) ethnic groups. In terms of teaching experience, three teachers had over 10 years of experience, two had between 5 and 10 years, and four had less than five years. All participants had implemented the a Kurikulum Merdeka, Indonesia’s national curriculum that emphasizes student-centered learning.

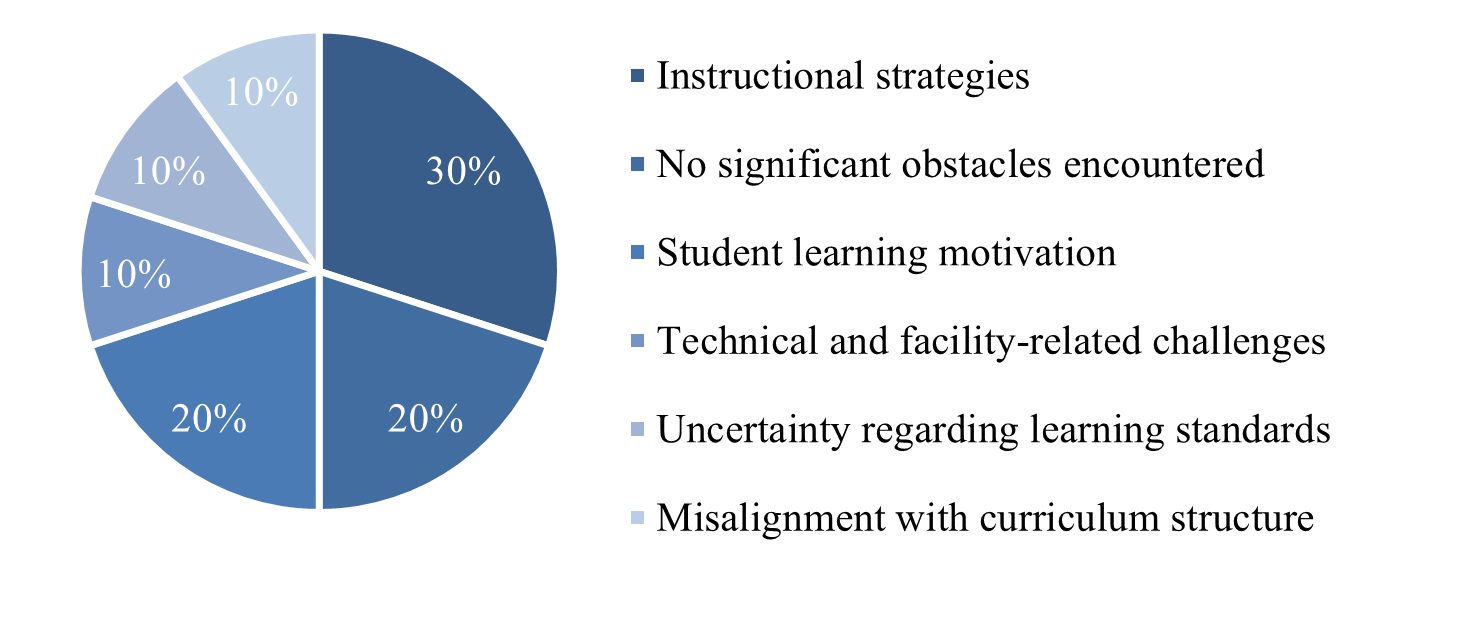

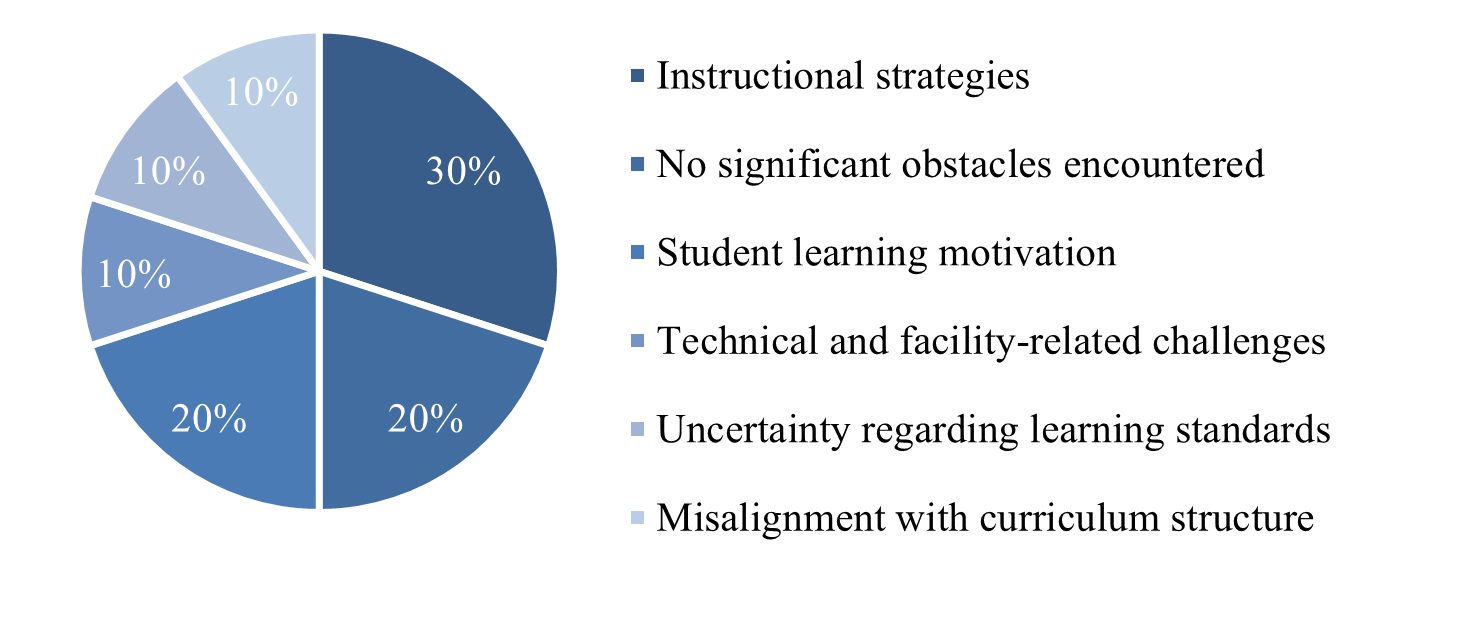

- Barriers to Teaching

Figure 2 presents a summary of the barriers to teaching. The majority of teachers (90%) reported facing at least one challenge in implementing chemistry learning, while only one teacher (10%) stated that they encountered no significant obstacles. The most frequently mentioned barrier was instructional strategies (30%), followed by technical and facility-related challenges (20%), and student learning motivation (20%). In addition, uncertainty regarding learning standards (10%) and misalignment with curriculum structure (10%) were also reported. Although the total number of participants was nine (n = 9), the percentage distribution in Figure 2 was rounded to the nearest ten for visual clarity. Hence, the values do not directly correspond to the fractional percentages that would otherwise appear (e.g., 11.1%, 22.2%). Moreover, each teacher could report multiple barriers simultaneously, resulting in a cumulative percentage that exceeds 100%. This approach was used to more clearly illustrate the relative prominence of each theme rather than to represent mutually exclusive participant counts.

Figure 2. Barriers to Teaching

A teacher from a remote area highlighted that the lack of infrastructure and teaching resources posed a major challenge, while several others emphasized difficulties in adopting new pedagogical approaches such as Differentiated Learning, Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL), Culturally Responsive Teaching (CRT), Social Emotional Learning (SEL), and Developmentally Appropriate Practice (DAP). One teacher shared:

“The emergence of these multiple pedagogical approaches requires me not only to understand them but also to implement them effectively in the classroom. In response to these developments, my school has organized several In-House Trainings (IHT) involving lecturers from teacher education institutions and school supervisors, as well as established teacher learning communities that focus on sharing best practices in instructional implementation. However, in my view, these efforts have not been sufficient to fully equip me. Therefore, I have taken the initiative to seek additional knowledge and understanding by attending various seminars and online webinars, which I have then tried to apply in my chemistry teaching practices”.

This statement highlights the increasing complexity of pedagogical expectations under the Kurikulum Merdeka, which requires both instructional adaptation and a shift in pedagogical mindset toward more student-cantered and inclusive practices. The finding that teachers struggled to adopt innovative pedagogical approaches aligns with prior research on curriculum reform in Indonesia and other developing contexts [48] [49]. These studies similarly report that limited professional development, insufficient infrastructure, and time constraints often hinder teachers from effectively implementing new instructional models. For example, [50] observed that teachers’ reliance on traditional methods can impede the transition toward more student-centered practices, while [51] and [52] emphasized that ongoing collaboration with teacher education institutions is critical for building sustainable pedagogical change.

These findings suggest that curriculum innovation must be accompanied by continuous, practical, and contextually relevant professional learning opportunities. Teachers require not only theoretical knowledge but also hands-on guidance to implement pedagogical innovations that reflect students’ diverse backgrounds and learning needs. The teacher’s proactive efforts to seek external learning opportunities demonstrate professional agency and lifelong learning, essential qualities for navigating dynamic educational reforms. However, the limited depth and sustainability of institutional training such as IHT and learning communities indicate that these initiatives often remain surface-level and lack follow-up support. Additionally, 20% of teachers reported low student motivation as a major challenge, which aligns with [53], who noted that the lack of contextual relevance in chemistry instruction often reduces students’ engagement. This finding reinforces the need for context-based and culturally responsive approaches to connect chemistry concepts with students’ everyday experiences.

This section benefits from a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative summaries with qualitative teacher reflections to enrich the interpretation of findings. The inclusion of teachers from diverse school settings provided valuable insight into the contextual barriers faced under the Kurikulum Merdeka. However, given the small sample size and the non-exclusive categorization of responses, the percentages should be interpreted as indicative rather than absolute. Future studies with larger samples and direct classroom observations could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the systemic and contextual factors that influence teachers’ ability to implement curriculum reform.

- Instructional Models and Approaches

Based on the questionnaire results, discovery learning emerged as the most commonly used instructional model, frequently integrated with the scientific approach. Teachers perceived this model as effective for enhancing students’ engagement and conceptual understanding in chemistry. However, several teachers reported that low student motivation remained an obstacle, suggesting that the discovery learning model may not be equally effective in all classroom contexts. In contrast, a few teachers who had begun implementing CRT observed that this approach fostered more interactive and meaningful learning experiences by connecting lesson content with students’ cultural backgrounds. One teacher expressed:

“In Indonesia, with its diversity of values, beliefs, ethnicities, and cultural backgrounds, these factors influence students’ behavior and interactions. Therefore, the CRT approach is important to integrate cultural aspects into learning”.

This view illustrates a growing awareness among teachers of the pedagogical value of integrating cultural dimensions into classroom practice. The finding that discovery learning is dominant aligns with prior studies indicating that Indonesian science teachers tend to favor constructivist models consistent with the scientific approach emphasized in the national curriculum [19],[55]. However, the limited mention of CRT suggests that culturally oriented pedagogy remains underdeveloped in mainstream chemistry education. This contrasts with international research showing that CRT significantly enhances student motivation, engagement, and achievement, particularly in diverse classrooms classroom [54]. Similar trends have been observed in multicultural science education, where connecting local culture to scientific content has been found to promote deeper conceptual understanding [52].

The present findings imply that while discovery learning supports inquiry-based engagement, it may not fully address the affective and sociocultural dimensions of student learning. Incorporating CRT can help bridge this gap by linking chemistry concepts with students’ everyday experiences and cultural practices. In Indonesia’s multicultural classrooms, this approach may strengthen students’ sense of belonging and relevance in learning, thereby improving motivation and participation. For example, CRT-based chemistry lessons could connect green chemistry principles with local wisdom, such as the use of natural dyes in batik production or environmentally friendly material processing. Such connections make chemistry more tangible, meaningful, and contextually grounded for students.

A notable strength of this finding is that it captures teachers’ emerging recognition of the importance of culturally relevant pedagogy, which reflects a progressive shift in teaching philosophy under the Kurikulum Merdeka. However, the limited number of teachers who have adopted CRT indicates that its implementation is still in an exploratory stage. This limitation may stem from insufficient training or lack of instructional models that explicitly integrate CRT principles within the chemistry curriculum. Future studies should further explore how CRT can be systematically combined with inquiry-based models such as discovery or problem-based learning to enhance both cognitive and cultural dimensions of chemistry education.

- Teachers’ Understanding of CRT

The results revealed that only two out of nine teachers demonstrated a clear understanding of CRT, both of whom had less than five years of teaching experience. Meanwhile, four teachers had never heard of CRT, two were only vaguely familiar with it, and one held a misconception about its meaning. These findings indicate a limited awareness and conceptual clarity of CRT among Indonesian chemistry teachers, despite increasing emphasis on inclusive and student-centered pedagogies in recent years. One teacher described CRT as follows:

“Yes, I have heard of Culturally Responsive Teaching (CRT), which is an approach to education that recognizes and values the cultural diversity of students. This concept focuses on implementing teaching strategies that are sensitive to students' cultural backgrounds and how these backgrounds can influence the way they learn and interact in the classroom”.

Another teacher shared her practical experience:

“During the Teacher Professional Education Program, I integrated Culturally Responsive Teaching (CRT) into my lesson by using a worksheet that featured a narrative text related to Palembang culture.”

These responses reflect varying levels of understanding and application, ranging from conceptual awareness to partial implementation. This indicates that although some teachers attempt to integrate cultural elements, they tend to equate CRT with the mere inclusion of local cultural content rather than recognizing it as a comprehensive pedagogical framework for fostering culturally responsive learning. This limited awareness of CRT among chemistry teachers is consistent with findings from previous studies indicating that science teachers often lack sufficient understanding of culturally responsive pedagogy, particularly in subject-specific contexts such as chemistry [56]. Similar trends have been observed in other countries, where teachers acknowledge the importance of cultural diversity but struggle to operationalize CRT principles in practice [57]. However, the finding that younger teachers (with less than five years of experience) demonstrated higher familiarity with CRT aligns with research suggesting that newer teacher education curricula have begun incorporating inclusive and culturally responsive pedagogical frameworks more explicitly [58].

The findings highlight a critical need to strengthen professional development and pre-service teacher education related to CRT, especially within STEM and chemistry education. Misconceptions, such as equating CRT solely with the teaching of local culture, indicate that teachers may not yet fully understand the holistic nature of CRT, which encompasses not only the integration of cultural content but also the creation of inclusive classroom interactions, the validation of diverse student identities, and the promotion of equitable learning experiences [59]. Moreover, several teachers appeared to apply CRT principles unconsciously, for instance by using Bahasa Indonesia to ensure inclusivity in linguistically diverse classrooms:

“I’ve never explicitly implemented CRT, but maybe I’ve applied it without realizing it. Since my students come from different ethnic groups, I use Bahasa Indonesia so as not to favor the dominant group in class.”

This statement suggests that elements of CRT naturally emerge in teachers’ daily practices, even without formal awareness. Therefore, targeted professional training is essential to transform these implicit practices into intentional, reflective, and systematic CRT implementation. This is especially important for teaching abstract and culturally neutral topics such as stoichiometry, where contextual and cultural connections can make learning more meaningful.

A key strength of this finding lies in its ability to uncover the implicit awareness and emerging practices of CRT among teachers, indicating a foundation upon which future training can build. However, the small sample size ( ) limits the generalizability of the results, and self-reported data may not fully capture teachers’ actual classroom behaviors. Future research involving classroom observations or lesson analyses would provide richer insights into how teachers interpret and enact CRT in practice. Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable evidence that Indonesian chemistry teachers, particularly early-career educators, have begun to engage with culturally responsive principles, representing an important step toward more inclusive and equitable chemistry education.

) limits the generalizability of the results, and self-reported data may not fully capture teachers’ actual classroom behaviors. Future research involving classroom observations or lesson analyses would provide richer insights into how teachers interpret and enact CRT in practice. Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable evidence that Indonesian chemistry teachers, particularly early-career educators, have begun to engage with culturally responsive principles, representing an important step toward more inclusive and equitable chemistry education.

- Integrating Local Culture in Stoichiometry Instruction

The analysis revealed that chemistry teachers held varied perspectives regarding the integration of students’ cultural backgrounds into stoichiometry instruction. Four major subthemes emerged: (1) enhancing meaningful learning, (2) cultural integration as a contextual entry point, (3) limited teacher knowledge, and (4) cultural sensitivity in diverse classrooms.

Most teachers (44.4%) believed that connecting stoichiometry lessons with local cultural contexts enhances students’ engagement and conceptual understanding. Examples such as using local vinegar from pempek to discuss acidity and concentration demonstrated how cultural contexts make abstract chemical ideas more tangible. Meanwhile, a smaller proportion (11.1%) viewed culture mainly as an introductory context to stimulate interest before transitioning to more conventional stoichiometric problem-solving exercises. Others (11.1%) admitted struggling to relate chemistry with culture due to limited pedagogical knowledge, and one teacher (11.1%) highlighted the challenge of cultural diversity in classrooms where students have different linguistic or ethnic backgrounds.

These findings resonate with previous studies that emphasize the role of culturally relevant contexts in promoting meaningful science learning [60]. Similar to the results reported by [61], the integration of cultural and local wisdom-based examples facilitates students’ conceptual understanding while fostering positive attitudes toward chemistry learning. Likewise, [62] argued that CRT enhances both cognitive and affective dimensions of learning by bridging students’ cultural experiences with academic content. However, consistent with the findings of [63] and [64], this study also highlights that teachers often face pedagogical and epistemological challenges in implementing such approaches in chemistry, which is perceived as abstract and decontextualized.

The results suggest that integrating culture into stoichiometry instruction can foster more meaningful and relevant learning, allowing students to connect chemical concepts with everyday phenomena and local practices. Cultural contexts can serve as powerful entry points for inquiry and discussion, yet procedural fluency still requires structured practice with symbolic representations and quantitative reasoning. Therefore, teacher professional development programs should not only emphasize content mastery but also equip teachers with practical strategies for contextual and culturally responsive chemistry teaching. This includes providing examples of culturally relevant teaching modules, contextual problems, and assessment models aligned with local realities. Moreover, the issue of cultural and linguistic diversity in classrooms underscores the need for inclusive strategies that acknowledge and value multiple cultural identities while maintaining equitable participation for all students.

A key strength of this study lies in its in-depth exploration of teachers’ nuanced perspectives, providing meaningful insights into how the principles of culturally responsive teaching can be operationalized within chemistry instruction, particularly in the complex context of stoichiometry. However, the study’s small sample size ( ) limits the generalizability of these findings. Future research could involve a larger and more diverse teacher population or adopt classroom-based observations to triangulate teachers’ self-reported data with actual instructional practices. Despite these limitations, the study contributes an important lens for understanding the intersection between culture and chemistry education, especially in multicultural and multilingual contexts like Indonesia.

) limits the generalizability of these findings. Future research could involve a larger and more diverse teacher population or adopt classroom-based observations to triangulate teachers’ self-reported data with actual instructional practices. Despite these limitations, the study contributes an important lens for understanding the intersection between culture and chemistry education, especially in multicultural and multilingual contexts like Indonesia.

- Implementing Stoichiometry Learning with a Green Chemistry Orientation

The findings revealed limited implementation of green chemistry-oriented stoichiometry instruction among participating teachers. Only two out of nine teachers (22.22%) reported using problem-based learning (PBL), while two others relied primarily on traditional lecture-based approaches. Three teachers mentioned incorporating multimedia tools such as videos and visual aids, and one implemented laboratory-based learning. Another teacher applied differentiated instruction to accommodate students’ diverse learning needs.

In terms of explicitly integrating green chemistry principles, seven teachers admitted they had never connected stoichiometric concepts with environmental or sustainability issues. In contrast, two teachers demonstrated initial efforts by contextualizing stoichiometry through real-world industrial processes emphasizing waste reduction and reactant efficiency. For example, one teacher used the context of ammonia and biodiesel production to discuss how optimizing the molar ratio of reactants can minimize by-products and environmental impact.

Several barriers were identified: limited instructional time (44.44%), lack of suitable references and teaching resources (33.33%), and the perceived abstractness and difficulty of stoichiometric calculations (33.33%). Three teachers reported no particular challenges, primarily because they had not yet attempted to integrate GC principles into their instruction.

These findings are consistent with earlier studies indicating that chemistry teachers often struggle to integrate sustainability and environmental contexts into core topics such as stoichiometry [65]. Similar to research by [66], the present study confirms that teachers’ limited awareness and pedagogical resources hinder the translation of green chemistry principles into classroom practice. Moreover, previous studies [67] have emphasized that the successful implementation of green chemistry-oriented instruction requires not only conceptual understanding of chemistry but also teachers’ competence in designing contextually relevant problems and assessments.

The findings suggest that while teachers recognize the potential of contextualized learning, the actual adoption of green chemistry principles in stoichiometry remains minimal. This gap highlights a need for targeted professional development programs focusing on sustainable chemistry pedagogy, particularly in integrating environmental ethics and resource efficiency into quantitative chemistry topics. The few teachers who contextualized stoichiometry through industrial examples demonstrate the feasibility of embedding green chemistry concepts even in traditionally abstract content. Such approaches can help students connect theoretical calculations with real-world environmental implications, thereby promoting both chemical literacy and environmental responsibility. Integrating green chemistry also aligns with the goals of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), which encourages learners to engage critically with global challenges such as pollution and resource depletion.

However, the dominant reliance on lecture-based teaching and the perceived difficulty of stoichiometric calculations indicate that teachers often prioritize procedural mastery over conceptual and contextual understanding. Therefore, curriculum developers and teacher educators should collaborate to design teaching materials, sample lesson plans, and laboratory activities that embed green chemistry contexts without compromising core content learning.

A key strength of this study is its detailed exploration of teachers’ instructional strategies and barriers related to green chemistry integration, providing valuable insights into how sustainability concepts are perceived within the domain of stoichiometry teaching. However, the limited sample size ( ) restricts the generalizability of findings and may not capture the full variation of practices across different school types or regions. Additionally, data were derived primarily from self-reported questionnaire responses, which may not fully represent actual classroom practices. Future research could employ classroom observations or lesson plan analyses to verify how teachers operationalize green chemistry principles in practice. Despite these limitations, the findings highlight an important area for intervention in chemistry teacher education to promote environmentally responsible teaching practices.

) restricts the generalizability of findings and may not capture the full variation of practices across different school types or regions. Additionally, data were derived primarily from self-reported questionnaire responses, which may not fully represent actual classroom practices. Future research could employ classroom observations or lesson plan analyses to verify how teachers operationalize green chemistry principles in practice. Despite these limitations, the findings highlight an important area for intervention in chemistry teacher education to promote environmentally responsible teaching practices.

- Teachers’ Needs

To examine teachers’ perspectives on the relevance and support needed for implementing CRT in stoichiometry learning with a green chemistry orientation, two open-ended questions were analyzed regarding the necessity of CRT and teachers’ perceived needs for implementation. Thematic analysis of responses from nine teachers revealed two main themes: (1) perceptions of CRT relevance and (2) practical needs for implementation.

In terms of perceptions, the majority of teachers (55.56%) strongly supported CRT, emphasizing that integrating cultural and environmental contexts could enhance students’ chemical literacy and cultural awareness. A smaller group (22.22%) expressed conditional or moderate support, stressing the need for clear implementation steps, while another 22.22% showed skepticism, perceiving CRT as less relevant for conceptually demanding topics like stoichiometry.

Regarding teachers’ needs, two primary areas emerged. First, most teachers (66.67%) requested concrete teaching materials, such as culturally contextualized modules, worksheets, and assessment formats, to facilitate practical classroom implementation. Second, some teachers (22.22%) emphasized the need for professional development programs that enhance both cultural literacy and pedagogical skills. These findings indicate that although teachers recognize CRT’s potential, effective implementation requires accessible resources and sustained professional support.

The current findings align with previous research highlighting the importance of culturally relevant instructional materials in supporting CRT practices. Studies such as [68] assert that without concrete teaching resources, teachers struggle to connect abstract scientific concepts with students’ cultural experiences. Similarly, in chemistry education, context-based learning approaches have been found to make learning more meaningful and relatable [18]. Moreover, the teachers’ expressed need for professional development mirrors prior findings by [69], who note that effective CRT implementation depends on teachers’ ability to integrate cultural responsiveness with strong pedagogical content knowledge (PCK). In science education specifically, researchers such as [70] and [71] argue that teachers often require targeted training to bridge scientific content with local or indigenous knowledge systems.

However, the skepticism expressed by a few teachers regarding CRT’s applicability to stoichiometry reveals a contrast with studies (e.g., [72][73]) that view socio-scientific and culturally embedded contexts as powerful tools for teaching abstract chemistry topics. This discrepancy may reflect differences in teacher readiness, exposure to CRT concepts, or the availability of institutional support for culturally contextualized science education.

The findings suggest that teachers generally view CRT as a valuable pedagogical framework for making stoichiometry learning more relevant and engaging, particularly when linked to green chemistry principles. However, the varying levels of understanding and readiness among teachers indicate the need for systemic support. Providing accessible and contextually grounded instructional materials such as lesson plans that connect chemical calculations with local environmental phenomena, including waste management, traditional fermentation, or sustainable production, could facilitate a more effective implementation of culturally responsive teaching.

Furthermore, the teachers’ calls for professional development indicate that implementing CRT is not merely a matter of material provision but also of capacity building. Programs should therefore focus on cultivating teachers’ cultural competence, pedagogical creativity, and critical reflection on diversity in learning. When teachers develop both PCK and cultural literacy, they can design chemistry lessons that are not only scientifically rigorous but also culturally inclusive and socially meaningful.

In addition, skepticism toward CRT’s cognitive relevance underscores a common misconception that cultural integration detracts from scientific rigor. On the contrary, research demonstrates that culturally relevant contexts can enhance cognitive engagement by situating abstract concepts within familiar realities, thereby deepening conceptual understanding and motivation. Addressing this misconception through training and collaborative lesson design could help teachers see CRT as complementary, rather than supplementary, to cognitive learning goals.

A strength of this study lies in its detailed exploration of teachers’ needs and perceptions, revealing nuanced insights into both enthusiasm and hesitation toward applying a CRT approach oriented toward green chemistry in chemistry education. The combination of teachers’ qualitative reflections and thematic coding provides a grounded understanding of practical challenges faced by educators in diverse classrooms.

However, the study’s small sample size ( ) limits the generalizability of findings across broader teacher populations. Furthermore, data were self-reported and may not fully capture teachers’ actual classroom practices or institutional barriers. Future studies could employ classroom observations, lesson plan analyses, or intervention-based research to examine how teachers apply CRT principles in practice. Despite these limitations, the findings highlight an urgent need for systemic teacher support through the development of instructional materials and the provision of professional learning opportunities to advance culturally responsive and sustainable chemistry education.

) limits the generalizability of findings across broader teacher populations. Furthermore, data were self-reported and may not fully capture teachers’ actual classroom practices or institutional barriers. Future studies could employ classroom observations, lesson plan analyses, or intervention-based research to examine how teachers apply CRT principles in practice. Despite these limitations, the findings highlight an urgent need for systemic teacher support through the development of instructional materials and the provision of professional learning opportunities to advance culturally responsive and sustainable chemistry education.

- CONCLUSIONS

This study explored chemistry teachers’ perceptions of implementing CRT within stoichiometry instruction oriented toward green chemistry. The findings indicate that while teachers generally value the integration of cultural relevance and environmental sustainability in chemistry learning, practical implementation remains limited. A notable insight is the conflation of CRT with ethnochemistry, reflecting a conceptual misunderstanding that constrains teachers’ ability to design pedagogically sound CRT-oriented green chemistry lessons. Teachers recognized the potential of green chemistry principles to enhance contextual and sustainability-based learning. However, challenges such as limited time, inadequate resources, and insufficient professional development hinder their classroom application. These barriers underscore the importance of supporting teachers through targeted professional learning programs and the development of culturally contextualized teaching materials. Future research should involve a larger and more diverse sample to validate these findings and explore effective models for teacher professional development. Additionally, experimental studies could be conducted to implement CRT-oriented green chemistry instruction and examine its impact on students’ chemical literacy and cultural awareness. Such efforts would strengthen the empirical foundation for integrating sustainability and cultural responsiveness in science education.

DECLARATION

Author Contribution

All authors contributed equally to the main contributor to this paper. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Acknowledgement

This research was funded by Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta through the Riset Kolaborasi Indonesia (RKI) program under contract number T/18.1.11/UN34.9/PT.01.03/2024. The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta and all partners involved for their support and collaboration in completing this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- V. Briller, “Beyond the classroom: My journey through education a tale of two educational worlds,” Int. J. Educ. Dev., vol. 111, p. 103166, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2024.103166.

- B. Theeuwes, N. Saab, E. Denessen, and W. Admiraal, “Unraveling teachers’ intercultural competence when facing a simulated multicultural classroom,” Teach. Teach. Educ., vol. 162, p. 105053, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2025.105053.

- Sukidin, C. Hudha, and Basrowi, “Shaping democracy in Indonesia: The influence of multicultural attitudes and social media activity on participation in public discourse and attitudes toward democracy,” Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open, vol. 11, p. 101440, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2025.101440.

- S. Rahayu, “Socio-scientific Issues (SSI) in Chemistry Education: Enhancing Both Students’ Chemical Literacy & Transferable Skills,” J. Phys. Conf. Ser., vol. 1227, no. 1, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1227/1/012008.

- Susilawati, N. Aznam, Paidi, and I. Irwanto, “Socio-scientific issues as a vehicle to promote soft skills and environmental awareness,” Eur. J. Educ. Res., vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 161–174, 2021, https://doi.org/10.12973/EU-JER.10.1.161.

- Y. Rahmawati, A. Mardiah, E. Taylor, P. C. Taylor, and A. Ridwan, “Chemistry Learning through Culturally Responsive Transformative Teaching (CRTT): Educating Indonesian High School Students for Cultural Sustainability,” Sustain., vol. 15, no. 8, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086925.

- S. M. Kernaghan, T. Coady, M. Kinsella, and C. M. Lennon, “A tutorial review for research laboratories to support the vital path toward inherently sustainable and green synthetic chemistry,” RSC Sustain., vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 578–607, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1039/d3su00324h.

- R. A. Mashami, Ahmadi, and Pahriah, “Green chemistry and cultural wisdom: A pathway to improving scientific literacy among high school students,” Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open, vol. 11, no. December 2024, p. 101653, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2025.101653.

- C. A. Thomas, “District Certified Culturally Responsive Elementary Teachers and Their Mathematics Teaching Practices,” J. Urban Math. Educ., vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 10–47, 2024, https://doi.org/10.21423/jume-v17i1a480.

- D. H. Siswanto, H. Kuswantara, and N. Wahyuni, “Implementation of Problem Based Learning Approach Culturally Responsive Teaching to Enhance Engagement and Learning Outcomes in Algebraic Function Limit Material,” EDUCATUM Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 80–88, 2024, https://doi.org/10.37134/ejsmt.vol12.1.9.2025.

- J. Meléndez-Luces and P. Couto-Cantero, “Engaging ethnic-diverse students: A research based on culturally responsive teaching for roma-gypsy students,” Educ. Sci., vol. 11, no. 11, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110739.

- Y. Zeng, H. F. Isleem, G. G. Tejani, A. Jahami, and K. A. Alnowibet, “Examining the impact of culturally responsive teaching and identity affirmation on student outcomes: A mixed-methods study in diverse educational settings,” Int. J. Educ. Dev., vol. 117, p. 103376, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2025.103376.

- A. I. Oladejo, P. A. Okebukola, T. T. Olateju, V. O. Akinola, A. Ebisin, and T. V. Dansu, “In Search of Culturally Responsive Tools for Meaningful Learning of Chemistry in Africa: We Stumbled on the Culturo-Techno-Contextual Approach,” J. Chem. Educ., vol. 99, no. 8, pp. 2919–2931, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.2c00126.

- H. Pratomo, N. Fitriyana, A. Wiyarsi, and Marfuatun, “Mapping chemistry learning difficulties of secondary school students: a cross-grade study,” J. Educ. Learn., vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 909–920, 2025, https://doi.org/10.11591/edulearn.v19i2.21826.

- I. W. Redhana, I. N. Suardana, I. N. Selamat, I. B. N. Sudria, and K. N. Karyawati, “A green chemistry teaching material: Its validity, practicality, and effectiveness on redox reaction topics,” In AIP Conference Proceedings, vol. 2330, no. 1, p. 020023, 20221, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0043213.

- S. Oberleiter, J. Fries, L. S. Schock, B. Steininger, and J. Pietschnig, “Predicting cross-national sex differences in large-scale assessments of students’ reading literacy, mathematics, and science achievement: Evidence from PIRLS and TIMSS,” Intelligence, vol. 100, p. 101784, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2023.101784.

- C. Kalinec-Craig and A. Rios, “An exploratory mixed methods study about teacher candidates’ descriptions of children’s confusion, productive struggle, and mistakes in an elementary mathematics methods course,” J. Math. Behav., vol. 73, p. 101103, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmathb.2023.101103.

- O. Gulacar, C. Zowada, S. Burke, A. Nabavizadeh, A. Bernardo, and I. Eilks, “Integration of a sustainability-oriented socio-scientific issue into the general chemistry curriculum: Examining the effects on student motivation and self-efficacy,” Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy, vol. 15, p. 100232, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scp.2020.100232.

- E. Ellizar, H. Hardeli, S. Beltris, and R. Suharni, “Development of scientific approach based on discovery learning module,” In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, vol. 335, p. 012101, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/335/1/012101.

- R. Hari, S. Geraghty, and K. Kumar, “Clinical supervisors’ perspectives of factors influencing clinical learning experience of nursing students from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds during placement: A qualitative study,” Nurse Educ. Today, vol. 102, p. 104934, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104934.

- N. M. Redmond, J. Shubert, P. C. Scales, J. Williams, and A. K. Syvertsen, “Unveiling potential: Culturally responsive teaching practices to catalyze social-emotional success in black youth,” Soc. Emot. Learn. Res. Pract. Policy, vol. 5, p. 100124, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sel.2025.100124.

- Y. Rahmawati and A. Ridwan, “Empowering students’ chemistry learning: The integration of ethnochemistry in culturally responsive teaching,” Chem. Bulg. J. Sci. Educ., vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 813–830, 2017, https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=600081.

- D. Diiorio, See Me, Hear Me, Teach Me: Addressing Equity, Diversity, and Student Engagement through Culturally Responsive Teaching. Sacred Heart University, 2022, https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/edd/14/.

- H. S. A. Fitri, E. Putri, and S. Chuchai, “Trends in Culturally Responsive Teaching for Science EducationL A Bibliometric Analysis,” J. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. Dev., vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 36–52, 2025, https://doi.org/10.59247/jtped.vli2.13.

- B. C. O’Brien and A. Battista, “Situated learning theory in health professions education research: a scoping review,” Adv. Heal. Sci. Educ., vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 483–509, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-019-09900-w.

- Y. Rahmawati, A. Ridwan, and Nurbaity, “Should we learn culture in chemistry classroom? Integration ethnochemistry in culturally responsive teaching,” In AIP Conference Proceedings, vol. 1868, no. 1, p. 030009, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4995108.

- C. Mayusoh, “The Art of Designing, Fabric Pattern by Tie-dyeing with Natural Dyes,” Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci., vol. 197, no. February, pp. 1472–1480, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.07.097.

- T. Keinonen and T. de Jager, “Student teachers’ perspectives on chemistry education in South Africa and Finland,” J. Sci. Teacher Educ., vol. 28, no. 6, pp. 485–506, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1080/1046560X.2017.1378055.

- F. A. Etzkorn and J. L. Ferguson, “Integrating Green Chemistry into Chemistry Education,” Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed., vol. 62, no. 2, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202209768.

- E. Burhanuddin, M. Danial, M. Arsyad, and S. Zubair, “Development of green chemistry teaching modules based on project based learning in class X,” J. Educ. Anal., vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 355–366, 2025, https://doi.org/10.55927/jeda.v4i2.92.

- J. Vogelzang, W. F. Admiraal, and J. H. Van Driel, “Effects of Scrum methodology on students’ critical scientific literacy: The case of Green Chemistry,” Chem. Educ. Res. Pract., vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 940–952, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1039/d0rp00066c.

- R. D. Hardianti and I. U. Wusqo, “Fostering students’ scientific literacy and communication through the development of collaborative-guided inquiry handbook of green chemistry experiments,” J. Phys. Conf. Ser., vol. 1567, no. 2, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1567/2/022059.

- Z. Wang, C. McLenahan, and L. Abraham, “Using soapnut extract as a natural surfactant in green chemistry education: a laboratory experiment aligning with UN SDG 12 for general chemistry courses,” RSC Sustain., vol. 2, no. 12, pp. 3788–3797, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1039/d4su00397g.

- L. Mammino, “Cross-bridging green chemistry education and environmental chemistry education,” Sustain. Chem. Environ., vol. 9, no. December 2024, p. 100195, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scenv.2024.100195.

- L. K. Wardani et al., “Effect of an Ethnochemistry-based Culturally Responsive Teaching Approach to Improve Cognitive Learning Outcomes on Green Chemistry Material in High School,” J. Penelit. Pendidik. IPA, vol. 9, no. 12, pp. 11029–11037, 2023, https://doi.org/10.29303/jppipa.v9i12.5532.

- S. Sudarmin, E. Selia, and M. Taufiq, “The influence of inquiry learning model on additives theme with ethnoscience content to cultural awareness of students,” J. Phys. Conf. Ser., vol. 983, no. 1, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/983/1/012170.

- A. Wiyarsi, A. K. Prodjosantoso, and A. R. E. Nugraheni, “Students’ chemical literacy level: A case on electrochemistry topic,” J. Phys. Conf. Ser., vol. 1440, no. 1, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1440/1/012019.

- C. Cigdemoglu and O. Geban, “Improving Students’ Chemical Literacy Level on Thermochemical and Thermodynamics Concepts through Context-Based Approach,” J. Mater. Chem. C, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 302–317, 2015, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1039/C5RP00007F.

- M. Istyadji and Sauqina, “Conception of scientific literacy in the development of scientific literacy assessment tools: a systematic theoretical review,” J. Turkish Sci. Educ., vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 281–308, 2023, https://doi.org/10.36681/tused.2023.016.

- M. Weingarden, “Exploring pre-service mathematics teachers’ perspectives on balancing student struggle and concept attention,” Teach. Teach. Educ., vol. 165, , p. 105143, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2025.105143.

- K. K. Frankel, M. D. Brooks, and J. E. Learned, “Teachers’ perspectives on the structure of reading intervention classes in secondary schools: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research,” Teach. Teach. Educ., vol. 162, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2025.105029.

- R. Thind and H. Yakavenka, “Creating culturally relevant curricula and pedagogy: Rethinking fashion business and management education in UK business schools,” Int. J. Manag. Educ., vol. 21, no. 3, p. 100870, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2023.100870.

- Y. Rahmawati, A. Ridwan, A. Rahman, and F. Kurniadewi, “Chemistry students’ identity empowerment through etnochemistry in culturally responsive transformative teaching (CRTT),” J. Phys. Conf. Ser., vol. 1156, no. 1, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1156/1/012032.

- Y. Rahmawati, H. R. Baeti, A. Ridwan, S. Suhartono, and R. Rafiuddin, “A culturally responsive teaching approach and ethnochemistry integration of Tegal culture for developing chemistry students’ critical thinking skills in acid-based learning,” J. Phys. Conf. Ser., vol. 1402, no. 5, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1402/5/055050.

- R. Yerrick and M. Ridgeway, “Culturally responsive pedagogy, science literacy, and urban underrepresented science students,” Int. Perspect. Incl. Educ., vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 87–103, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-363620170000011007.

- J. C. Brown and K. J. Crippen, “Designing for culturally responsive science education through professional development,” Int. J. Sci. Educ., vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 470–492, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2015.1136756.

- V. Braun and V. Clarke, “Qualitative Research in Psychology Using thematic analysis in psychology Using thematic analysis in psychology,” Qual. Res. Psychol., vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 77–101, 2006, https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- A. Wiyarsi, A. K. Prodjosantoso, and A. R. E. Nugraheni, “Promoting Students’ Scientific Habits of Mind and Chemical Literacy Using the Context of Socio-Scientific Issues on the Inquiry Learning,” Front. Educ., vol. 6, no. May, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.660495.

- A. Wiyarsi, H. Pratomo, and E. Priyambodo, “Vocational high school students’ chemical literacy on context-based learning: A case of petroleum topic,” J. Turkish Sci. Educ., vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 147–161, 2020, https://doi.org/10.36681/tused.2020.18.

- D. Bailey, M. Kornegay, L. Partlow, C. Bowens, K. Gareis, and K. Kornegay, “Utilizing Culturally Responsive Strategies to Inspire African American Female Participation in Cybersecurity,” J. Pre-College Eng. Educ. Res., vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 118–128, 2023, https://doi.org/10.7771/2157-9288.1412.

- P. Widyastuti, M. Dos, and J. Leonard, “Mapping Digital Learning Transformation for 21st Century Skills: A Bibliometric Analysis,” J. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. Dev., vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 53–65, 2024, https://doi.org/10.59247/jtped.v1i2.14.

- J. A. Ogodo, “Culturally Responsive Pedagogical Knowledge: An Integrative Teacher Knowledge Base for Diversified STEM Classrooms,” Educ. Sci., vol. 14, no. 2, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020124.

- A. C. Anyichie, D. L. Butler, and S. M. Nashon, “Exploring teacher practices for enhancing student engagement in culturally diverse classrooms,” J. Pedagog. Res., vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 183–207, 2023, https://doi.org/10.33902/JPR.202322739.

- Y. L. Wah and N. B. M. Nasri, “A Systematic Review: The Effect of Culturally Responsive Pedagogy on Student Learning and Achievement,” Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci., vol. 9, no. 5, pp. 588–596, 2019, https://doi.org/10.6007/ijarbss/v9-i5/5907.

- Zafrullah, M. H. M. Majid, H. Syukur, M. N. M. Rumais, Haidir, and M. A. P. Putra, “Technological Trends in Indonesian Educational Research : A Bibliometric Analysis,” J. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. Dev., vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 1–12, 2024, https://doi.org/10.59247/jtped.v1i2.14.

- Y. Rahmawati, A. Ridwan, U. Cahyana, and D. Febriana, “The integration of culturally responsive transformative teaching to enhance student cultural identity in the chemistry classroom,” Univers. J. Educ. Res., vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 468–476, 2020, https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2020.080218.

- P. J. Mellom, R. Straubhaar, C. Balderas, M. Ariail, and P. R. Portes, “They come with nothing: How professional development in a culturally responsive pedagogy shapes teacher attitudes towards Latino/a English language learners,” Teach. Teach. Educ., vol. 71, pp. 98–107, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.12.013.

- J. Kehl, P. Krachum Ott, M. Schachner, and S. Civitillo, “Culturally responsive teaching in question: A multiple case study examining the complexity and interplay of teacher practices, beliefs, and microaggressions in Germany,” Teach. Teach. Educ., vol. 152, no. September, p. 104772, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2024.104772.

- J. B. Underwood and F. M. Mensah, “An Investigation of Science Teacher Educators’ Perceptions of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy,” J. Sci. Teacher Educ., vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 46–64, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1080/1046560X.2017.1423457.

- I. S. Azis, S. D. Maharani, and V. I. Indralin, “Implementation of differentiated learning with a Culturally Responsive Teaching approach to increase students’ interest in learning,” J. Elem. Edukasia, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 2750–2758, 2024, https://doi.org/10.31949/jee.v7i2.9348.

- E. S. O’Leary et al., “Creating inclusive classrooms by engaging STEM faculty in culturally responsive teaching workshops,” Int. J. STEM Educ., vol. 7, no. 1, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-020-00230-7.

- H. Ghaemi and N. Boroushaki, “Culturally responsive teaching in diverse classrooms: A framework for teacher preparation program,” Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 102433-102433, 2025, https://doi.org/10.29140/ajal.v8n1.102433.

- E. Ukwandu, O. Omisade, K. Jones, S. Thorne, and M. Castle, “The future of teaching and learning in the context of emerging artificial intelligence technologies,” Futures, vol. 171, no. May, pp. 1–16, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2025.103616.

- A. Göçen and M. F. Döğer, “Artificial Intelligence in Educational Leadership: A Global Bibliometric Analysis,” J. Educ. Res., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1–14, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2025.2510397.

- V. G. Zuin, I. Eilks, M. Elschami, and K. Kümmerer, “Education in green chemistry and in sustainable chemistry: perspectives towards sustainability,” Green Chem., vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 1594–1608, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1039/d0gc03313h.

- T. L. Chen, H. Kim, S. Y. Pan, P. C. Tseng, Y. P. Lin, and P. C. Chiang, “Implementation of Green Chemistry Principles in Circular Economy System Towards Sustainable Development Goals: Challenges and perspectives,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 716, no. 1, p. 136998, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136998.

- K. Kiwfo et al., “Sustainable education with local-wisdom based natural reagent for green chemical analysis with a smart device: experiences in Thailand,” Sustain., vol. 13, no. 20, pp. 1–12, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011147.

- N. Chow-Garcia et al., “Cultural identity central to Native American persistence in science,” Cultural Studies of Science Education, vol. 17, no. 2, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-021-10071-7.

- M. Beth Schlemper, S. Shetty, O. Yamoah, K. Czajkowski, and V. Stewart, “Culturally Responsive Teaching through Spatial Justice in Urban Neighborhoods,” Urban Educ., vol. 60, no. 2, pp. 343–377, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1177/00420859231153411.

- P. García-Llamas, A. Taboada, P. Sanz-Chumillas, L. Lopes Pereira, and R. Baelo Álvarez, “Breaking barriers in STEAM education: Analyzing competence acquisition through project-based learning in a European context,” Int. J. Educ. Res. Open, vol. 8, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2025.100449.

- M. Çalik and A. Wiyarsi, “The effect of socio-scientific issues-based intervention studies on scientific literacy: a meta-analysis study,” Int. J. Sci. Educ., pp. 1–23, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2024.2325382.

- P. L. Pence and V. M. Wright, “U.S. graduate nurses transition into practice: Perspectives on simulation-based education and cultural awareness in caring for diverse patients,” Nurse Educ. Pract., vol. 87, p. 104477, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2025.104477.

- N. V. Khamsiah, S. Chandech, K. Kusumawardhani, R. Hayati, and N. Ramadana, “Trends in Pedagogical Research in Learning Environments: A Scopus-Based Bibliometric Analysis (2000–2025),” J. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. Dev., vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 36–52, 2025, https://doi.org/10.59247/jtped.v2i3.32.

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

| Hajidah Salsabila Allissa Fitri, received a Bachelor’s degree in Chemistry Education. She is currently pursuing a Master’s program in Yogyakarta under the LPDP scholarship. She is an educator in the field of chemistry, actively contributing through academic journal articles and content on social media. In 2024, she co-authored the book Pendidikan Inklusif: Mengeksplorasi Keberagaman dan Kesetaraan. Her research interests include inclusive education, socio-scientific issues, and chemistry education innovations. E-mail: hajidahsalsabila.2023@student.uny.ac.id |

|

|

| Antuni Wiyarsi, received a Ph.D. degree in Science Education from Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia in 2013. She is currently a Professor at the Department of Chemistry Education, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta. Her research interests include chemistry education, socio-scientific issues, scientific habits of mind, and green and sustainable chemistry education. She has also served as a visiting scholar in Turkey, initiating international collaborations in chemistry education research and academic exchange. E-mail: antuni_w@uny.ac.id |

|

|

| Hayuni Retno Widarti, received her doctoral degree in Chemistry Education from Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia. She is currently a Professor at the Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Universitas Negeri Malang. Her research interests focus on chemistry education, green chemistry, environmental education, and the development of learning models that promote students’ scientific literacy and higher-order thinking skills. She has published numerous articles in national and international journals and actively contributes to research and curriculum development in sustainable chemistry education. E-mail: hayuni.retno.fmipa@um.ac.id |

|

|

| Sri Yamtinah, earned her doctoral degree in Chemistry Education from Universitas Sebelas Maret, Indonesia, where she currently serves as a Professor at the Department of Chemistry Education. Her research interests encompass chemistry education, green and sustainable chemistry, socio-scientific issues, and the development of learning strategies to foster students’ scientific literacy and character education. She has authored numerous publications in national and international journals and actively engages in advancing innovative and contextual chemistry learning in Indonesia. E-mail: jengtina@staff.uns.ac.id |

|

|

| Yunilia Nur Pratiwi, earned her master’s degree in Chemistry Education from Universitas Sebelas Maret, Indonesia. She is currently a lecturer at the Department of Chemistry Education, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Universitas Sebelas Maret. Her research interests include chemistry education, green chemistry-oriented learning, scientific literacy, and the integration of socio-scientific issues in science teaching. She is actively involved in research and community service projects that promote sustainable and culturally responsive chemistry education. E-mail: yunilianurpratiwi@uny.ac.id |

Hajidah Salsabila Allissa Fitri (Exploring Teachers' Perspectives on Culturally Responsive Teaching in Stoichiometry Learning Oriented to Green Chemistry)