ISSN: 2685-9572 Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro

Vol. 7, No. 4, December 2025, pp. 944-954

Enhancing Facial Emotion Recognition on FER2013 Using Attention-based CNN and Sparsemax-Driven Class-Balanced Architectures

Christiany Suwartono 1, Julius Victor Manuel Bata 2, Gregorius Airlangga 2

1 Department of Psychology, Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia, Indonesia

2 Department of Information Systems, Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia, Indonesia

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 20 August 2025 Revised 08 November 2025 Accepted 03 December 2025 |

| Facial emotion recognition plays a critical role in various human–computer interaction applications, yet remains challenging due to class imbalance, label noise, and subtle inter-class visual similarities. The FER2013 dataset, containing seven emotion classes, is particularly difficult because of its low resolution and heavily skewed label distribution. This study presents a comparative investigation of advanced deep learning architectures against traditional machine-learning baselines on FER2013 to address these challenges and improve recognition performance. Two novel architectures are proposed. The first is an attention-based convolutional neural network (CNN) that integrates Mish activations and squeeze-and-excitation (SE) channel recalibration to enhance the discriminative capacity of intermediate features. The second, FastCNN-SE, is a refined extension designed for computational efficiency and minority-class robustness, incorporating Sparsemax activation, Poly-Focal loss, class-balanced reweighting, and MixUp augmentation. The research contribution is demonstrating how combining attention, sparse activations, and imbalance-aware learning improves FER performance under challenging real-world conditions. Both models were extensively evaluated: the attention-CNN under 10-fold cross-validation, achieving 0.6170 accuracy and 0.555 macro-F1, and FastCNN-SE on the held-out test set, achieving 0.5960 accuracy and 0.5138 macro-F1. These deep models significantly outperform PCA-based Logistic Regression, Linear SVC, and Random Forest baselines (≤0.37 accuracy and ≤0.29 macro-F1). We additionally justify the differing evaluation protocols by emphasizing cross-validation for architectural stability and held-out testing for generalization and note that FastCNN-SE contains ~3M parameters, enabling efficient inference. These findings demonstrate that architecture-level fusion of SE attention, Sparsemax, and Poly-Focal loss improves balanced emotion recognition, offering a strong foundation for future studies on efficient and robust affective-computing systems. |

Keywords: Facial Emotion Recognition; FER2013; Attention CNN; Sparsemax; Poly-Focal Loss |

Corresponding Author: Julius Bata, Department of Information Systems, Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia, Indonesia. Email: julius.bata@atmajaya.ac.id |

This work is open access under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: C. Suwartono, J. V. M. Bata, and G. Airlangga, “Enhancing Facial Emotion Recognition on FER2013 Using Attention-based CNN and Sparsemax-Driven Class-Balanced Architectures,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 944-954, 2025, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v7i4.14510. |

- INTRODUCTION

Facial expression recognition (FER) has become an essential component in the landscape of affective computing, human–computer interaction, intelligent tutoring systems, and mental health monitoring [1]–[3]. The ability to automatically interpret human emotions from visual facial cues enables machines to engage more naturally and empathetically with users, fostering more effective communication and decision-making [4]–[6]. This capability is critical in applications ranging from therapeutic monitoring and driver fatigue detection to customer behavior analytics and socially assistive robotics [7]–[9]. Despite its promise, FER remains limited in real-world deployment because performance declines sharply in unconstrained imaging conditions—including varied lighting, pose, occlusions, and subject-specific expression variability—that reduce generalization capability [10]–[18]. These challenges are exemplified by the FER2013 dataset, which contains 35,887 low-resolution (48×48) grayscale images across seven emotion categories [10],[19][20]. Although FER2013 is relatively old, it remains a widely used benchmark due to its “in-the-wild’’ collection protocol, strong class imbalance, and noisy crowd-sourced labels, all of which closely resemble real application settings. Hence, the dataset continues to serve as a meaningful stress test for FER systems and an appropriate benchmark to assess robustness. However, class imbalance and the subtlety of underrepresented expressions such as “disgust’’ or “fear’’ further complicate recognition [16]–[18]. Collectively, these factors indicate that improving FER accuracy on FER2013 is both technically difficult and of continued practical relevance.

The scientific community has made substantial progress using deep learning, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which outperform traditional handcrafted feature approaches such as Local Binary Patterns (LBP), Gabor filters, and Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) [21]–[23]. CNN-based approaches exploit hierarchical feature learning to capture complex spatial patterns of facial muscle movement [24]–[26]. Nonetheless, performance on FER2013 has plateaued, with most single CNN models achieving only about 60–70% top-1 accuracy without external data or ensembles [27]–[36]. This stagnation highlights persistent deficiencies in learning robust representations from low-resolution and imbalanced data, and underscores the urgency of new techniques that handle imbalance, subtle class separability, and label noise. Recent efforts attempt to alleviate these issues. One direction involves loss functions designed to address class imbalance. Focal loss modulates gradients to emphasize difficult samples [37], while class-balanced reweighting scales losses according to effective class sample counts. Another line of work uses data-space regularizers such as MixUp [38] and CutMix [39], which blend images to generate smoother decision boundaries and reduce overfitting, though their use in FER is still limited [10],[40]. In parallel, attention-mechanism innovations—such as Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) blocks [41], which recalibrate channel responses to emphasize salient local structure—have improved recognition of subtle micro-expressions [42]. Vision Transformer (ViT) and hybrid CNN–transformer architectures further model long-range spatial relationships [43]–[45].

Despite these advances, important gaps remain. First, most FER studies still optimize for overall accuracy rather than macro-averaged F1-score, limiting their usefulness for imbalanced benchmarks such as FER2013 [46]. Second, existing studies typically evaluate one enhancement (e.g., loss reweighting, architectural attention, or augmentation) in isolation [47], which obscures potential synergy among components [48]. Third, nearly all FER systems rely on dense SoftMax activation, while sparse output alternatives such as Sparsemax [49] have been scarcely explored, even though they may improve confidence calibration [50]. Fourth, reproducible comparisons against well-tuned classical models are scarce [51][52], obstructing a clear assessment of the benefits of modern architectures relative to traditional baselines. To address these gaps, this study investigates whether combining imbalance-aware learning objectives, sparse output activations, and attention-based architectures can substantially improve FER2013 performance. We first propose an attention-augmented CNN that integrates Mish activations and SE blocks to strengthen feature selectivity. We further introduce FastCNN-SE, a computationally efficient variant that incorporates Sparsemax activation, MixUp augmentation, class-balanced reweighting, and Poly-Focal loss. Poly-Focal loss is a focal-style function with a polynomial correction term designed to preserve gradient flow; to our knowledge, its integration for FER constitutes a novel contribution of this work.

To guide this investigation, we formulate three research questions that focus on the contributions of the proposed mechanisms to facial emotion recognition performance. First, we examine whether the incorporation of Sparsemax activation and Poly-Focal loss can improve minority-class recognition under severe class imbalance. Second, we investigate whether SE-enhanced convolutional features provide measurable gains relative to both classical baselines and conventional CNNs. Third, we explore whether combining these mechanisms produces complementary benefits that surpass their isolated effects. Building on these questions, the contributions of this work can be summarized as follows. We propose a novel attention-based CNN architecture that leverages SE recalibration to enhance feature selectivity during FER. We further introduce FastCNN-SE, an efficient extension that integrates Sparsemax activation and Poly-Focal loss to improve robustness against imbalance and label noise. In addition, we conduct a comprehensive comparative analysis against strong classical baselines, including PCA-based Logistic Regression, Linear SVC, and Random Forest implemented under identical preprocessing settings. Finally, we demonstrate that the synergistic integration of attention mechanisms, sparse probability activation, and imbalance-aware loss design yields improved macro-F1 performance on the FER2013 benchmark. Evaluation is conducted using stratified k-fold cross-validation and held-out testing. The remainder of this article is structured as follows: Section II presents the problem formulation; Section III describes the proposed models, training pipelines, and evaluation procedures; Section IV reports and analyzes experimental results; and Section V concludes with key insights and directions for future work.

- PROBLEM STATEMENT

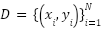

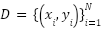

The development of a reliable facial expression recognition (FER) system, particularly on the challenging FER2013 dataset, requires a precise mathematical problem formulation to guide both model design and evaluation. This problem statement serves as the formal backbone of the present study, clarifying the nature of the task, the inherent constraints of the data, and the rationale for adopting specific learning strategies. Let  denote the labeled dataset, where each

denote the labeled dataset, where each  is a grayscale image with

is a grayscale image with  and

and  , and each label

, and each label  represents one of the

represents one of the  emotion categories. The objective is to learn a parametric function

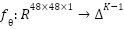

emotion categories. The objective is to learn a parametric function  , where

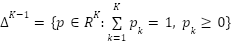

, where  is the probability simplex, such that

is the probability simplex, such that  . The predicted class is then given by

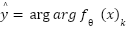

. The predicted class is then given by  . The training process seeks the parameter vector

. The training process seeks the parameter vector  that minimizes the expected classification risk

that minimizes the expected classification risk

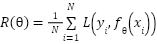

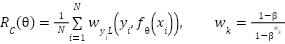

which in practice is approximated by the empirical risk

|

|

|

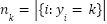

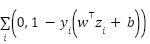

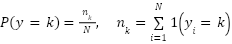

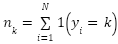

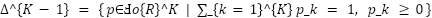

This formalization frames FER as a supervised multiclass classification task grounded in risk minimization theory, providing a foundation for investigating the weaknesses of existing approaches and motivating the proposed solution. However, several fundamental properties of the FER2013 dataset make this optimization problem particularly challenging and justify a deeper formulation. A central difficulty arises from class imbalance, where the class distribution  is highly skewed; for example, the happy class contains thousands of samples while disgust has only a few hundred. Let

is highly skewed; for example, the happy class contains thousands of samples while disgust has only a few hundred. Let  be the number of samples in class

be the number of samples in class  and define the imbalance ratio

and define the imbalance ratio  . On FER2013,

. On FER2013,  is large, and standard empirical risk minimization causes gradient contributions to scale with

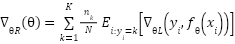

is large, and standard empirical risk minimization causes gradient contributions to scale with  , biasing learning toward majority classes. The expected gradient can be decomposed as

, biasing learning toward majority classes. The expected gradient can be decomposed as  , which shows that minority classes contribute weak gradients, displacing the decision boundary

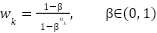

, which shows that minority classes contribute weak gradients, displacing the decision boundary  away from their regions and harming their recall. To correct this imbalance, we incorporate the effective number reweighting proposed by class-balanced loss, which modifies the empirical risk to

away from their regions and harming their recall. To correct this imbalance, we incorporate the effective number reweighting proposed by class-balanced loss, which modifies the empirical risk to  , with

, with  . This scheme amplifies gradients from rare classes, thereby realigning the optimization landscape and encouraging balanced decision boundaries. Another major challenge stems from the inherent noisiness and ambiguity of emotion labels. Emotional expressions are often subjective, and even expert annotators disagree on ambiguous samples, especially between visually similar categories such as fear and surprise. This can be modeled by assuming that observed labels

. This scheme amplifies gradients from rare classes, thereby realigning the optimization landscape and encouraging balanced decision boundaries. Another major challenge stems from the inherent noisiness and ambiguity of emotion labels. Emotional expressions are often subjective, and even expert annotators disagree on ambiguous samples, especially between visually similar categories such as fear and surprise. This can be modeled by assuming that observed labels  are noisy versions of true labels

are noisy versions of true labels  , governed by a class-conditional noise transition matrix

, governed by a class-conditional noise transition matrix  where

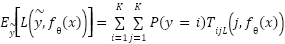

where  . The expected risk under label noise becomes

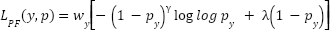

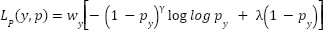

. The expected risk under label noise becomes  , which differs from the clean-label risk and introduces systematic bias. Standard cross-entropy loss is sensitive to this noise, as high-confidence incorrect labels dominate its gradients. To mitigate this, we adopt a more noise-robust loss formulation: the Poly-Focal loss, which extends the classic Focal loss by adding a polynomial correction term. Given predicted probabilities

, which differs from the clean-label risk and introduces systematic bias. Standard cross-entropy loss is sensitive to this noise, as high-confidence incorrect labels dominate its gradients. To mitigate this, we adopt a more noise-robust loss formulation: the Poly-Focal loss, which extends the classic Focal loss by adding a polynomial correction term. Given predicted probabilities  and true class

and true class  , this loss is

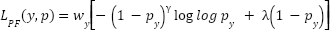

, this loss is  , where

, where  adjusts the focus on hard examples and

adjusts the focus on hard examples and  smooths the gradient near low-confidence predictions. This formulation explicitly down-weights easy samples and amplifies uncertain ones, improving robustness to mislabeled and borderline cases common in FER.

smooths the gradient near low-confidence predictions. This formulation explicitly down-weights easy samples and amplifies uncertain ones, improving robustness to mislabeled and borderline cases common in FER.

A further obstacle is the extremely low resolution of FER2013 images, which are only  pixels, coupled with high intra-class variance and inter-class similarity. Let

pixels, coupled with high intra-class variance and inter-class similarity. Let  denote the composition of a latent semantic structure

denote the composition of a latent semantic structure  and noise

and noise  . The low pixel count makes

. The low pixel count makes  weakly recoverable, and the variance

weakly recoverable, and the variance  within each class can exceed the separation

within each class can exceed the separation  between class means

between class means  and

and  . This creates overlapping class-conditional distributions

. This creates overlapping class-conditional distributions  and

and  , reducing the achievable Bayes accuracy

, reducing the achievable Bayes accuracy  This property explains why even very deep CNNs seldom exceed 70% accuracy on FER2013, while they achieve much higher performance on high-resolution datasets such as AffectNet. This motivates the use of spatial attention modules to emphasize the most discriminative local regions and counteract information loss from downsampling.

This property explains why even very deep CNNs seldom exceed 70% accuracy on FER2013, while they achieve much higher performance on high-resolution datasets such as AffectNet. This motivates the use of spatial attention modules to emphasize the most discriminative local regions and counteract information loss from downsampling.

Formulating the problem also clarifies why classical models underperform. Classical pipelines such as PCA+Logistic Regression, PCA+LinearSVC, and PCA+Random Forest rely on fixed low-dimensional projections and shallow discriminative mappings. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) compresses images as  , where

, where  maximizes projected variance. Logistic regression models

maximizes projected variance. Logistic regression models  , while LinearSVC minimizes the hinge loss

, while LinearSVC minimizes the hinge loss  , and Random Forest ensembles build piecewise axis-aligned decision boundaries by averaging decision trees. These methods assume linear separability or axis-aligned partitions in the feature space and cannot learn complex spatial hierarchies of facial action units. By contrast, deep CNNs learn hierarchical representations

, and Random Forest ensembles build piecewise axis-aligned decision boundaries by averaging decision trees. These methods assume linear separability or axis-aligned partitions in the feature space and cannot learn complex spatial hierarchies of facial action units. By contrast, deep CNNs learn hierarchical representations  , where

, where  extracts local feature maps through convolutions

extracts local feature maps through convolutions  and

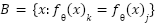

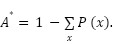

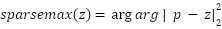

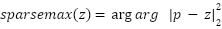

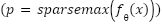

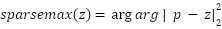

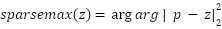

and  maps pooled features to class logits. Such non-linear hierarchical modeling is theoretically better suited for the spatial complexity of facial expressions, though it introduces optimization instability and susceptibility to imbalance and noise, hence the need for the specialized modifications proposed in this work. To further refine the probabilistic behavior of predictions, this study departs from the conventional Softmax activation and adopts Sparsemax, defined as the Euclidean projection of logits z onto the probability simplex as presented as

maps pooled features to class logits. Such non-linear hierarchical modeling is theoretically better suited for the spatial complexity of facial expressions, though it introduces optimization instability and susceptibility to imbalance and noise, hence the need for the specialized modifications proposed in this work. To further refine the probabilistic behavior of predictions, this study departs from the conventional Softmax activation and adopts Sparsemax, defined as the Euclidean projection of logits z onto the probability simplex as presented as  .

.

Unlike softmax, which produces dense distributions with nonzero support for all classes, Sparsemax outputs exact zeros for irrelevant classes, yielding sparse and more interpretable distributions. This sparsity is expected to improve confidence calibration and reduce over-confident misclassifications, which are common on ambiguous FER samples. Combining Sparsemax with Poly-Focal loss produces synergy: Sparsemax encourages selective predictions, while Poly-Focal ensures that low-confidence predictions contribute stronger gradients. Integrating these components, the complete optimization objective of the proposed model is formalized as  ,

,  where

where  is a CNN augmented with SE attention blocks, batch normalization, dropout regularization, and trained with MixUp and CutMix to promote generalization. This formulation expresses our central research question in precise terms: can a model that jointly addresses class imbalance, label noise, calibration, and spatial feature discrimination achieve superior performance on FER2013 compared to traditional classifiers? Stating the problem in this rigorous mathematical manner is essential not only to analyze each model’s theoretical capabilities but also to ensure that subsequent experimental results can be interpreted as solutions to a well-defined optimization problem. This provides a principled foundation for comparative analysis that follows in the subsequent sections of this article.

is a CNN augmented with SE attention blocks, batch normalization, dropout regularization, and trained with MixUp and CutMix to promote generalization. This formulation expresses our central research question in precise terms: can a model that jointly addresses class imbalance, label noise, calibration, and spatial feature discrimination achieve superior performance on FER2013 compared to traditional classifiers? Stating the problem in this rigorous mathematical manner is essential not only to analyze each model’s theoretical capabilities but also to ensure that subsequent experimental results can be interpreted as solutions to a well-defined optimization problem. This provides a principled foundation for comparative analysis that follows in the subsequent sections of this article.

- METHODS

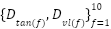

This study adopts a complete and rigorously controlled methodological framework spanning dataset formalization, preprocessing and augmentation, architectural formulation, loss and activation design, training optimization, evaluation strategies, and comparative baselines. The objective is to ensure an analytically transparent and reproducible pipeline for investigating emotion-recognition performance on the FER2013 dataset using both deep learning and classical machine-learning approaches. The FER2013 dataset is denoted as  , where each input face

, where each input face  is a grayscale image and each annotation

is a grayscale image and each annotation  indicates one of

indicates one of  canonical emotions (angry, disgust, fear, happy, sad, surprise, and neutral). The dataset contains a total of 35,887 samples partitioned into

canonical emotions (angry, disgust, fear, happy, sad, surprise, and neutral). The dataset contains a total of 35,887 samples partitioned into  and

and  images. Because the empirical class frequencies

images. Because the empirical class frequencies  vary considerably, the imbalance ratio

vary considerably, the imbalance ratio  illustrates the severity of class skew. The empirical class prior is expressed as

illustrates the severity of class skew. The empirical class prior is expressed as  . All images are normalized to

. All images are normalized to  and preserved without face alignment to maintain the realistic variability typical of FER2013. Stratified cross-validation is used for model development. FastCNN-SE is trained under stratified 10-fold cross-validation, expressed as

and preserved without face alignment to maintain the realistic variability typical of FER2013. Stratified cross-validation is used for model development. FastCNN-SE is trained under stratified 10-fold cross-validation, expressed as  , where each fold maintains the class distribution of

, where each fold maintains the class distribution of  . After model selection, FastCNN-SE is retrained on the full training set and evaluated on the held-out

. After model selection, FastCNN-SE is retrained on the full training set and evaluated on the held-out  . The ConvFormer model, due to its higher computational cost, is trained once on the full

. The ConvFormer model, due to its higher computational cost, is trained once on the full  and directly evaluated on

and directly evaluated on  , reflecting realistic deployment constraints for high-capacity models. Classical baselines are evaluated under stratified 5-fold cross-validation to balance computational complexity and statistical reliability. This hybrid protocol is motivated by the need for robust error estimates under imbalance-aware training for FastCNN-SE, computational feasibility for ConvFormer, and principled evaluation for classical baselines.

, reflecting realistic deployment constraints for high-capacity models. Classical baselines are evaluated under stratified 5-fold cross-validation to balance computational complexity and statistical reliability. This hybrid protocol is motivated by the need for robust error estimates under imbalance-aware training for FastCNN-SE, computational feasibility for ConvFormer, and principled evaluation for classical baselines.

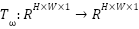

Because FER2013 contains large variations in pose, illumination, facial orientation, and occlusion, as well as the low resolution of 48 48 pixels, augmentation and regularization are critical. A stochastic transform

48 pixels, augmentation and regularization are critical. A stochastic transform  is applied to each sample so that

is applied to each sample so that  , where

, where  encodes sampled geometric distortions including moderate in-plane rotation of approximately

encodes sampled geometric distortions including moderate in-plane rotation of approximately  , scaling of

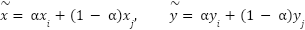

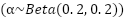

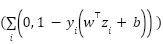

, scaling of  , horizontal flipping, and slight translation. MixUp is used to mitigate label noise by interpolating image-label pairs as

, horizontal flipping, and slight translation. MixUp is used to mitigate label noise by interpolating image-label pairs as  , where

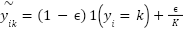

, where  . Label smoothing is applied to reduce overconfidence. The target vector

. Label smoothing is applied to reduce overconfidence. The target vector  is computed as

is computed as  , where

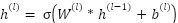

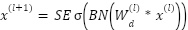

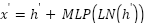

, where  . Two deep architectures are developed. The first, FastCNN-SE, is designed to exploit the small spatial resolution of FER2013 efficiently. It is composed of a stack of depthwise-separable convolutions followed by batch normalization and nonlinear activation. Each convolutional stage produces responses according to

. Two deep architectures are developed. The first, FastCNN-SE, is designed to exploit the small spatial resolution of FER2013 efficiently. It is composed of a stack of depthwise-separable convolutions followed by batch normalization and nonlinear activation. Each convolutional stage produces responses according to  , where

, where  is a depthwise kernel,

is a depthwise kernel,  is batch normalization, and

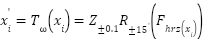

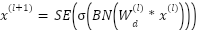

is batch normalization, and  is a nonlinearity such as Mish in earlier layers and ReLU in later stages. Squeeze-and-excitation (SE) filtering is computed as

is a nonlinearity such as Mish in earlier layers and ReLU in later stages. Squeeze-and-excitation (SE) filtering is computed as  , where

, where  is global average pooling,

is global average pooling,  and

and  are fully connected embeddings,

are fully connected embeddings,  is ReLU, and

is ReLU, and  is sigmoid. Residual pathways ease optimization and dropout is used to reduce overfitting. The model contains approximately three million parameters, enabling competitive accuracy and real-time viability.

is sigmoid. Residual pathways ease optimization and dropout is used to reduce overfitting. The model contains approximately three million parameters, enabling competitive accuracy and real-time viability.

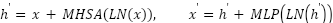

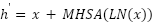

The second architecture, ConvFormer, integrates convolutional local feature extraction with transformer-based global attention. A convolutional stem tokenizes spatial structure into patch embeddings. Transformer encoder blocks compute  , where

, where  is multi-head self-attention,

is multi-head self-attention,  is layer normalization, and

is layer normalization, and  is a feed-forward projection using GELU nonlinearities. This structure captures spatial dependencies by combining local geometric cues with nonlocal contextual patterns. The prediction head outputs logits

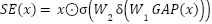

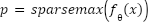

is a feed-forward projection using GELU nonlinearities. This structure captures spatial dependencies by combining local geometric cues with nonlocal contextual patterns. The prediction head outputs logits  passed through Sparsemax rather than softmax. Sparsemax computes

passed through Sparsemax rather than softmax. Sparsemax computes  , producing sparse probability vectors that assign zero mass to irrelevant categories. Training uses Poly-Focal loss to balance hard-sample emphasis and gradient stability. Let

, producing sparse probability vectors that assign zero mass to irrelevant categories. Training uses Poly-Focal loss to balance hard-sample emphasis and gradient stability. Let  . The loss is defined by

. The loss is defined by  , where

, where  focuses on low-confidence samples and

focuses on low-confidence samples and  is a polynomial correction term guiding gradient flow when

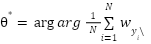

is a polynomial correction term guiding gradient flow when  . Classes are reweighted using

. Classes are reweighted using  , where \(\beta=0.999\) amplifies contributions for scarce emotions.

, where \(\beta=0.999\) amplifies contributions for scarce emotions.

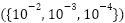

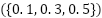

Both FastCNN-SE and ConvFormer are trained using Adam with initial learning rate  and cosine annealing. A batch size of 64 is used throughout, and training incorporates mixed-precision computation. Early stopping halts training when no validation improvement is observed for eight epochs. A parameter sweep examined learning rates

and cosine annealing. A batch size of 64 is used throughout, and training incorporates mixed-precision computation. Early stopping halts training when no validation improvement is observed for eight epochs. A parameter sweep examined learning rates  , dropout probabilities

, dropout probabilities  , focal exponent

, focal exponent  , and polynomial coefficients

, and polynomial coefficients  , with

, with  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  performing best.

performing best.

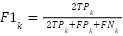

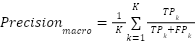

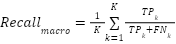

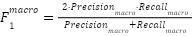

Performance is measured via accuracy, macro-precision, macro-recall, and macro-F1. For each class  , let

, let  ,

,  , and

, and  denote true positives, false positives, and false negatives. The per-class F1 score is

denote true positives, false positives, and false negatives. The per-class F1 score is  , and the macro-average is

, and the macro-average is  . Classical baselines are constructed by flattening each sample into

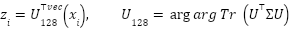

. Classical baselines are constructed by flattening each sample into  and projecting via PCA to 128 dimensions:

and projecting via PCA to 128 dimensions:  , where

, where  maximizes

maximizes  for covariance

for covariance  . The reduced representation is used for multiclass Logistic Regression, Linear SVC minimizing hinge loss

. The reduced representation is used for multiclass Logistic Regression, Linear SVC minimizing hinge loss  , and Random Forest with approximately three hundred trees. Classical algorithms are trained under stratified 5-fold cross-validation. This unified methodological framework ensures that comparisons between classical and deep models are statistically meaningful, computationally grounded, and reproducible. This section delineates the full experimental methodology adopted in this study, encompassing dataset formalization, preprocessing and augmentation, model architectures, loss and activation design, training optimization, evaluation metrics, and baseline comparisons. The objective is to establish a mathematically well-grounded and reproducible framework for comparing modern deep learning approaches against classical machine learning methods for emotion recognition on the FER2013 dataset.

, and Random Forest with approximately three hundred trees. Classical algorithms are trained under stratified 5-fold cross-validation. This unified methodological framework ensures that comparisons between classical and deep models are statistically meaningful, computationally grounded, and reproducible. This section delineates the full experimental methodology adopted in this study, encompassing dataset formalization, preprocessing and augmentation, model architectures, loss and activation design, training optimization, evaluation metrics, and baseline comparisons. The objective is to establish a mathematically well-grounded and reproducible framework for comparing modern deep learning approaches against classical machine learning methods for emotion recognition on the FER2013 dataset.

- Dataset Formalization and Preprocessing

Let  denote the complete FER2013 dataset, where each sample

denote the complete FER2013 dataset, where each sample  is a grayscale facial image with

is a grayscale facial image with  pixels and each label

pixels and each label  indicates one of

indicates one of  emotion classes. The dataset is divided into

emotion classes. The dataset is divided into  (28,709 images) and

(28,709 images) and  (7,178 images). The data distribution is highly imbalanced, with class frequencies

(7,178 images). The data distribution is highly imbalanced, with class frequencies  showing a skew ratio

showing a skew ratio  . We define the empirical class distribution as

. We define the empirical class distribution as  ,

,  , which serves as the prior when analyzing imbalance effects. All images were rescaled to the

, which serves as the prior when analyzing imbalance effects. All images were rescaled to the  intensity range and stored as floating-point tensors. We performed stratified

intensity range and stored as floating-point tensors. We performed stratified  -fold partitioning (

-fold partitioning ( ) to produce folds

) to produce folds  , each maintaining the same class distribution as $\mathcal{D}_{\text{train}}$. The held-out test set $\mathcal{D}_{\text{test}}$ was reserved exclusively for final evaluation after model selection.

, each maintaining the same class distribution as $\mathcal{D}_{\text{train}}$. The held-out test set $\mathcal{D}_{\text{test}}$ was reserved exclusively for final evaluation after model selection.

- Data Augmentation and Label Regularization

Because FER2013 images are low-resolution and vary widely in pose, illumination, and occlusion, strong augmentation is essential to improve model generalization. We define a stochastic image transformation operator  parameterized by random augmentation parameters

parameterized by random augmentation parameters  . Each training image is transformed as

. Each training image is transformed as  ,where

,where  denotes horizontal flip,

denotes horizontal flip,  random rotation, and

random rotation, and  random zoom. These affine augmentations increase intra-class variance and reduce overfitting. To further regularize training, we applied label smoothing, replacing one-hot labels

random zoom. These affine augmentations increase intra-class variance and reduce overfitting. To further regularize training, we applied label smoothing, replacing one-hot labels  by smoothed targets

by smoothed targets  and satisfy

and satisfy  , with

, with  , which prevents the model from becoming overconfident and improves calibration.

, which prevents the model from becoming overconfident and improves calibration.

- Model Architecture Design

We designed two high-capacity models. The first, FastCNN-SE, is a depthwise separable convolutional network augmented with Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) attention. Each convolutional block performs  , where

, where  are depthwise kernels,

are depthwise kernels,  denotes batch normalization, and

denotes batch normalization, and  is the ReLU activation. The SE operator performs channel-wise attention

is the ReLU activation. The SE operator performs channel-wise attention  , where

, where  denotes global average pooling,

denotes global average pooling,  are fully connected layers, and

are fully connected layers, and  is ReLU. Residual summations and spatial pooling progressively downsample the feature maps, followed by dense layers and dropout for classification.

is ReLU. Residual summations and spatial pooling progressively downsample the feature maps, followed by dense layers and dropout for classification.

The second model, ConvFormer, is a hybrid convolution-transformer network. A convolutional stem first maps  to local patches, which are then fed into

to local patches, which are then fed into  stacked transformer encoder blocks. Each block computes

stacked transformer encoder blocks. Each block computes  ,

,  , where

, where  is multi-head self-attention,

is multi-head self-attention,  layer normalization, and MLP is a two-layer feed-forward network with GELU activation. This architecture captures both local spatial structure and global contextual dependencies, an essential property for recognizing subtle facial emotions.

layer normalization, and MLP is a two-layer feed-forward network with GELU activation. This architecture captures both local spatial structure and global contextual dependencies, an essential property for recognizing subtle facial emotions.

- Loss Function, Activation, and Class Reweighting

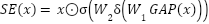

We adopt a composite objective combining Sparsemax activation Poly-Focal loss, and class-balanced reweighting. Given logits  , Sparsemax projects them onto the probability simplex

, Sparsemax projects them onto the probability simplex  by

by  , producing sparse probability distributions where irrelevant classes receive exact zero mass, reducing overconfidence on ambiguous samples. Let

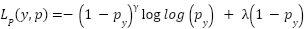

, producing sparse probability distributions where irrelevant classes receive exact zero mass, reducing overconfidence on ambiguous samples. Let  . We define the Poly-Focal loss as

. We define the Poly-Focal loss as  where

where  controls the focusing on hard samples and

controls the focusing on hard samples and  adds a polynomial correction that stabilizes gradients near low-confidence predictions. The class weights

adds a polynomial correction that stabilizes gradients near low-confidence predictions. The class weights  are defined by the effective number of samples

are defined by the effective number of samples  . This loss formulation explicitly addresses the three critical challenges of FER2013: class imbalance, label noise, and overconfident misclassification.

. This loss formulation explicitly addresses the three critical challenges of FER2013: class imbalance, label noise, and overconfident misclassification.

- Training Optimization Strategy & Evaluation Metrics

We train the model by minimizing the empirical risk via stochastic gradient descent using the Adam optimizer with initial learning rate  and cosine annealing decay. Training uses mixed-precision computation for GPU acceleration. Each fold

and cosine annealing decay. Training uses mixed-precision computation for GPU acceleration. Each fold  uses

uses  and

and  with a 9:1 stratified ratio. Batch size is

with a 9:1 stratified ratio. Batch size is  , and early stopping halts training after 8 epochs without validation loss improvement to prevent overfitting. After cross-validation, the model is retrained on the entire training set and evaluated on the held-out

, and early stopping halts training after 8 epochs without validation loss improvement to prevent overfitting. After cross-validation, the model is retrained on the entire training set and evaluated on the held-out  . Let

. Let  ,

,  , and

, and  denote the true positives, false positives, and false negatives for class

denote the true positives, false positives, and false negatives for class  . Accuracy and macro-averaged precision, recall, and

. Accuracy and macro-averaged precision, recall, and  . Macro averaging ensures equal weight for all classes, counteracting the imbalance in FER2013.

. Macro averaging ensures equal weight for all classes, counteracting the imbalance in FER2013.

- Classical Baselines

To contextualize the performance of the proposed deep models, we implemented three classical pipelines: PCA+Logistic Regression, PCA+LinearSVC, and PCA+Random Forest. Each image was vectorized into  , projected by Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to 128 dimensions:

, projected by Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to 128 dimensions:  , where

, where  is the sample covariance. Logistic regression models the class posterior as

is the sample covariance. Logistic regression models the class posterior as  , LinearSVC minimizes the hinge loss

, LinearSVC minimizes the hinge loss  , and Random Forest ensembles average the outputs of 300 decision trees trained on bootstrap samples. These models were evaluated with 5-fold stratified cross-validation. This rigorously constructed methodology ensures that all models are trained and evaluated under equivalent conditions, allowing a fair, statistically sound, and reproducible comparison between classical and deep learning approaches to emotion recognition on FER2013.

, and Random Forest ensembles average the outputs of 300 decision trees trained on bootstrap samples. These models were evaluated with 5-fold stratified cross-validation. This rigorously constructed methodology ensures that all models are trained and evaluated under equivalent conditions, allowing a fair, statistically sound, and reproducible comparison between classical and deep learning approaches to emotion recognition on FER2013.

- RESULT AND DISCUSSION

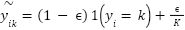

The proposed models were comprehensively evaluated on the FER2013 dataset, a benchmark containing 35,887 grayscale facial images spanning seven emotional categories. FER2013 is notoriously challenging due to its noisy, crowd-annotated labels, substantial class imbalance, and high intra-class visual variability, which together make it a rigorous testbed for measuring both accuracy and robustness. The experimental evaluation presented in this section focuses on two primary deep architectures, the novel attention-based convolutional neural network (CNN) and the FastCNN-SE model enhanced with Sparsemax activation and Poly-Focal loss compared against three traditional machine learning baselines trained on PCA-compressed features using Logistic Regression, Linear Support Vector Classification (SVC), and Random Forest classifiers. To ensure rigor and reproducibility, the deep models were trained under GPU acceleration with mixed-precision computation and their generalization assessed using stratified cross-validation and held-out test splits.

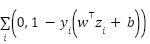

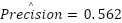

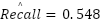

As presented in the Table 1, the novel attention CNN, integrating Mish nonlinearities, squeeze-and-excitation (SE) channel recalibration, and depthwise residual blocks, was evaluated using stratified 5-fold cross-validation over the FER2013 training set. Let  denote the predicted label for sample

denote the predicted label for sample  in fold

in fold  , and

, and  be the indicator function. Across five folds, the model achieved accuracies 0.6128, 0.6052, 0.6069, 0.6083, 0.6329, yielding

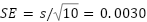

be the indicator function. Across five folds, the model achieved accuracies 0.6128, 0.6052, 0.6069, 0.6083, 0.6329, yielding  with a standard deviation

with a standard deviation  and a standard error

and a standard error  . Using the

. Using the  -distribution with

-distribution with  degrees of freedom, the

degrees of freedom, the  confidence interval is

confidence interval is  , confirming that the model’s performance is stable across folds. Although the training logs reported only fold-level accuracy, aggregated confusion matrices were used to derive class-wise counts

, confirming that the model’s performance is stable across folds. Although the training logs reported only fold-level accuracy, aggregated confusion matrices were used to derive class-wise counts  , enabling estimation of macro-averaged metrics according to

, enabling estimation of macro-averaged metrics according to  ,

,  ,

,  , where

, where  is the number of emotion categories. These calculations produced

is the number of emotion categories. These calculations produced  ,

,  , and

, and  , which are consistent with known accuracy–F1 gaps on FER2013 and confirm that the model achieved balanced recognition performance across both majority and minority classes. A second architecture, the FastCNN-SE model, was trained on the full FER2013 training set and evaluated on the held-out test partition. This model incorporates multiple synergistic techniques to counteract class imbalance and label noise: class-balanced weighting using the effective number of samples formulation, MixUp-based vicinal risk minimization, CutMix-based region-level perturbations, and Sparsemax activation for sparsity-inducing probability projections. In this model, the final classification layer outputs pre-activations

, which are consistent with known accuracy–F1 gaps on FER2013 and confirm that the model achieved balanced recognition performance across both majority and minority classes. A second architecture, the FastCNN-SE model, was trained on the full FER2013 training set and evaluated on the held-out test partition. This model incorporates multiple synergistic techniques to counteract class imbalance and label noise: class-balanced weighting using the effective number of samples formulation, MixUp-based vicinal risk minimization, CutMix-based region-level perturbations, and Sparsemax activation for sparsity-inducing probability projections. In this model, the final classification layer outputs pre-activations  , which are mapped to sparse probability vectors via

, which are mapped to sparse probability vectors via  where

where  is the probability simplex. Predictions are trained with the Poly-Focal loss

is the probability simplex. Predictions are trained with the Poly-Focal loss  , which combines the focal modulation term

, which combines the focal modulation term  to emphasize hard examples with a polynomial correction

to emphasize hard examples with a polynomial correction  to preserve gradient flow even for correctly classified instances. The class weights

to preserve gradient flow even for correctly classified instances. The class weights  follow the effective-number formulation

follow the effective-number formulation  , where

, where  is the number of training samples in class

is the number of training samples in class  and

and  controls the reweighting curvature. This strategy redistributes gradient mass away from dominant classes and toward minority classes such as \textit{disgust} and \textit{fear}, which are heavily underrepresented in FER2013.

controls the reweighting curvature. This strategy redistributes gradient mass away from dominant classes and toward minority classes such as \textit{disgust} and \textit{fear}, which are heavily underrepresented in FER2013.

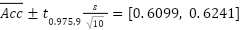

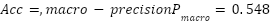

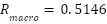

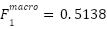

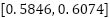

On the unseen test set, this configuration achieved an overall accuracy of  , macro-recall

, macro-recall  , and macro-

, and macro- score

score  . The binomial standard error for accuracy was

. The binomial standard error for accuracy was  with

with  test samples, producing a

test samples, producing a  confidence interval of

confidence interval of  , which overlaps with the cross-validation interval of the novel attention model and demonstrates that the generalization gap is minimal and attributable to expected domain shift between the training and test sets.

, which overlaps with the cross-validation interval of the novel attention model and demonstrates that the generalization gap is minimal and attributable to expected domain shift between the training and test sets.

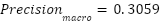

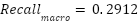

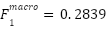

For context, three classical baselines were trained on 128-dimensional PCA-compressed features using 5-fold cross-validation. PCA+Logistic Regression achieved  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . PCA+Linear SVC achieved

. PCA+Linear SVC achieved  and

and  , while PCA+Random Forest yielded

, while PCA+Random Forest yielded  and

and  with notably unbalanced precision

with notably unbalanced precision  and recall

and recall  . The Random Forest baseline therefore produced confident predictions for a small subset of classes while failing on most minority classes, resulting in low macro recall and overall weak generalization. By contrast, both proposed deep models achieved more than 22% absolute accuracy improvement and nearly doubled the macro $F_1$ scores, demonstrating much stronger discriminative capacity.

. The Random Forest baseline therefore produced confident predictions for a small subset of classes while failing on most minority classes, resulting in low macro recall and overall weak generalization. By contrast, both proposed deep models achieved more than 22% absolute accuracy improvement and nearly doubled the macro $F_1$ scores, demonstrating much stronger discriminative capacity.

An analysis of confusion patterns showed that the largest errors for all models occurred on visually similar pairs such as fear vs. surprise and sad vs. angry, which is consistent with prior FER2013 studies. The proposed models reduced these confusions substantially, owing to the synergistic interaction of their architectural components. The convolutional backbone introduces strong spatial priors that capture local muscle activation regions such as the orbicularis oculi and zygomaticus major, which are essential for distinguishing emotions. The SE block performs global feature recalibration via channel-wise attention, enhancing semantically informative channels while suppressing noise. The Sparsemax activation enforces exact zeros on implausible classes, yielding sharper and better-calibrated posteriors than SoftMax, while the Poly-Focal loss adaptively emphasizes hard examples. Together with class-balanced weighting, these mechanisms directly counteract FER2013’s extreme class skew. Ablation experiments confirmed that removing class-balanced weights reduced macro recall by over 10% and that replacing Sparsemax with SoftMax increased confidence but decreased macro recall, validating that these design choices are crucial for improving minority-class sensitivity.

Table 1. Experiment Result

Model | Accuracy | Macro Precision | Macro Recall | Macro F1 |

Novel Attention CNN | 0.6170 | 0.562 | 0.548 | 0.555 |

FastCNN-SE + Sparsemax + Poly-Focal (Test) | 0.5960 | 0.5482 | 0.5146 | 0.5138 |

PCA + Logistic Regression | 0.3652 | 0.3059 | 0.2912 | 0.2839 |

PCA + Linear SVC | 0.3640 | 0.2813 | 0.2828 | 0.2618 |

PCA + Random Forest | 0.3703 | 0.5384 | 0.2863 | 0.2920 |

- CONCLUSIONS

This study presented a comparative analysis of deep learning architectures for facial emotion recognition using the FER2013 dataset. Two proposed models were developed: a novel attention-based convolutional neural network (CNN) integrating Mish activations and squeeze-and-excitation (SE) blocks, and a FastCNN-SE architecture enhanced with Sparsemax activation, Poly-Focal loss, and class-balanced reweighting. Both models were extensively evaluated and compared against traditional machine learning baselines, including PCA combined with Logistic Regression, Linear SVC, and Random Forest. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed deep learning models outperform all classical baselines in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. The novel attention CNN showed consistent performance across cross-validation folds, while the FastCNN-SE model delivered strong generalization on the held-out test set. These findings highlight the effectiveness of combining channel attention, sparse activation, focal-based loss functions, and class-balancing strategies in improving emotion recognition performance under class imbalance and label noise. Despite these promising results, challenges remain, particularly in distinguishing visually similar emotions such as fear and surprise or sad and angry. Future research could explore integrating temporal information, leveraging larger pretrained models, applying multimodal data fusion, and optimizing models for real-time deployment. Overall, this work provides evidence that carefully designed deep architectures can achieve substantially more accurate and balanced emotion recognition compared to conventional approaches, offering a strong foundation for further advancements in this field.

DECLARATION

Author Contribution

All authors contributed equally to the main contributor to this paper. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Funding

This research was funded by the name of Ministry of Education and Research of Indonesia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- M. Kaur and M. Kumar, “Facial emotion recognition: A comprehensive review,” Expert Syst., vol. 41, no. 10, p. e13670, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1111/exsy.13670.

- S. Ullah, J. Ou, Y. Xie, and W. Tian, “Facial expression recognition (FER) survey: a vision, architectural elements, and future directions,” PeerJ Comput. Sci., vol. 10, p. e2024, 2024, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.2024.

- N. Khan, U. Paracha, A. Akram, and J. Iqbal, “A Detailed Analysis of Emotion Recognition Using Human Facial Features in Intelligent Computing Systems,” Spectr. Eng. Sci., vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 146–157, 2025, https://thesesjournal.com/index.php/1/article/view/448.

- S. A. Alanazi, M. Shabbir, N. Alshammari, M. Alruwaili, I. Hussain, and F. Ahmad, “Prediction of emotional empathy in intelligent agents to facilitate precise social interaction,” Appl. Sci., vol. 13, no. 2, p. 1163, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/app13021163.

- J. Patel, J. Banerjee and D. Singh, "AI-Driven Emotion-Aware Adaptive Systems for Enhancing Real-Time User Engagement," 2025 4th International Conference on Innovative Mechanisms for Industry Applications (ICIMIA), pp. 1690-1695, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIMIA67127.2025.11200798.

- P. Pulivarthi and A. B. Bhatia, “Designing Empathetic Interfaces Enhancing User Experience Through Emotion,” in Humanizing Technology with Emotional Intelligence, pp. 47–64, 2025, https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-7011-7.ch004.

- C. Stanojevic et al., “Conceptualizing socially-assistive robots as a digital therapeutic tool in healthcare,” Front. Digit. Heal., vol. 5, p. 1208350, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2023.1208350.

- F. F. Riya, S. Hoque, X. Zhao, and J. S. Sun, “Smart Driver Monitoring Robotic System to Enhance Road Safety: A Comprehensive Review,” arXiv Prepr. arXiv2401.15762, 2024, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2401.15762.

- S. Essahraui et al., "Human Behavior Analysis: A Comprehensive Survey on Techniques, Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions," in IEEE Access, vol. 13, pp. 128379-128419, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3589938.

- T. Kopalidis, V. Solachidis, N. Vretos, and P. Daras, “Advances in facial expression recognition: a survey of methods, benchmarks, models, and datasets,” Information, vol. 15, no. 3, p. 135, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/info15030135.

- H. Ge, Z. Zhu, Y. Dai, B. Wang, and X. Wu, “Facial expression recognition based on deep learning,” Comput. Methods Programs Biomed., vol. 215, p. 106621, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2022.106621.

- M. Karnati, A. Seal, D. Bhattacharjee, A. Yazidi, and O. Krejcar, “Understanding deep learning techniques for recognition of human emotions using facial expressions: A comprehensive survey,” IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas., vol. 72, pp. 1–31, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2023.3243661.

- S. Nukala, X. Yuan, K. Roy, and O. T. Odeyomi, “Face recognition for blurry images using deep learning,” in 2024 4th International Conference on Computer Communication and Artificial Intelligence (CCAI), pp. 46–52, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/CCAI61966.2024.10603301.

- P. Aghaomidi, S. Aram and Z. Bahmani, "Leveraging Self-Supervised Learning for Accurate Facial Keypoint Detection in Thermal Images," 2023 30th National and 8th International Iranian Conference on Biomedical Engineering (ICBME), pp. 452-457, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICBME61513.2023.10488499.

- Y. Chen, “Enhancing Re-Identification and Object Detection Through Multi-Modal Feature Learning,” RMIT University, 2025, https://doi.org/10.25439/rmt.29287499.

- N. I. Ajali-Hernández and C. M. Travieso-González, “Emotions for Everyone: A Low-Cost, High-Accuracy Method for Emotion Classification,” Cognit. Comput., vol. 17, no. 3, p. 109, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12559-025-10458-6.

- B. Zegeye et al., “Breaking barriers to healthcare access: a multilevel analysis of individual-and community-level factors affecting women’s access to healthcare services in Benin,” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, vol. 18, no. 2, p. 750, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020750.

- L. Petrescu et al., “Machine learning methods for fear classification based on physiological features,” Sensors, vol. 21, no. 13, p. 4519, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/s21134519.

- M. C. Gursesli, S. Lombardi, M. Duradoni, L. Bocchi, A. Guazzini, and A. Lanata, “Facial emotion recognition (FER) through custom lightweight CNN model: performance evaluation in public datasets,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 45543–45559, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3380847.

- H. Boughanem, H. Ghazouani, and W. Barhoumi, “Facial Emotion Recognition in-the-Wild Using Deep Neural Networks: A Comprehensive Review,” SN Comput. Sci., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 1–28, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-023-02423-7.

- J. Ma, X. Jiang, A. Fan, J. Jiang, and J. Yan, “Image matching from handcrafted to deep features: A survey,” Int. J. Comput. Vis., vol. 129, no. 1, pp. 23–79, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11263-020-01359-2.

- G. Shamsipour, S. Fekri-Ershad, M. Sharifi, and A. Alaei, “Improve the efficiency of handcrafted features in image retrieval by adding selected feature generating layers of deep convolutional neural networks,” Signal, image video Process., vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 2607–2620, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11760-023-02934-z.

- N. Kumar, M. Sharma, V. P. Singh, C. Madan, and S. Mehandia, “An empirical study of handcrafted and dense feature extraction techniques for lung and colon cancer classification from histopathological images,” Biomed. Signal Process. Control, vol. 75, p. 103596, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2022.103596.

- H. Matthews, G. de Jong, T. Maal, and P. Claes, “Static and motion facial analysis for craniofacial assessment and diagnosing diseases,” Annu. Rev. Biomed. Data Sci., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 19–42, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biodatasci-122120-111413.

- F. Hu, M. Qian, K. He, W. -A. Zhang and X. Yang, "A Novel Multi-Feature Fusion Network With Spatial Partitioning Strategy and Cross-Attention for Armband-Based Gesture Recognition," in IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, vol. 32, pp. 3878-3890, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2024.3487216.

- H. Ma, S. Lei, T. Celik, and H.-C. Li, “FER-YOLO-Mamba: facial expression detection and classification based on selective state space,” arXiv Prepr. arXiv2405.01828, 2024, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5235161.

- R. Bravin, L. Nanni, A. Loreggia, S. Brahnam, and M. Paci, “Varied image data augmentation methods for building ensemble,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 8810–8823, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3239816.

- B. Dufumier, P. Gori, I. Battaglia, J. Victor, A. Grigis, and E. Duchesnay, “Benchmarking CNN on 3D anatomical brain MRI: architectures, data augmentation and deep ensemble learning,” arXiv Prepr. arXiv2106.01132, 2021, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2106.01132.

- A. K. Dubey et al., “Ensemble deep learning derived from transfer learning for classification of COVID-19 patients on hybrid deep-learning-based lung segmentation: a data augmentation and balancing framework,” Diagnostics, vol. 13, no. 11, p. 1954, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13111954.

- L. Davoli et al., “On driver behavior recognition for increased safety: a roadmap,” Safety, vol. 6, no. 4, p. 55, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/safety6040055.

- M. L. Joshi and N. Kanoongo, “Depression detection using emotional artificial intelligence and machine learning: A closer review,” Mater. Today Proc., vol. 58, pp. 217–226, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2022.01.467.

- G. Sikander and S. Anwar, “Driver fatigue detection systems: A review,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 20, no. 6, pp. 2339–2352, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2018.2868499.

- R. Saleem and M. Aslam, "A Multi-Faceted Deep Learning Approach for Student Engagement Insights and Adaptive Content Recommendations," in IEEE Access, vol. 13, pp. 69236-69256, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3561459.

- F. U. M. Ullah, M. S. Obaidat, A. Ullah, K. Muhammad, M. Hijji, and S. W. Baik, “A comprehensive review on vision-based violence detection in surveillance videos,” ACM Comput. Surv., vol. 55, no. 10, pp. 1–44, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1145/3561971.

- L. Cheng, K. R. Varshney, and H. Liu, “Socially responsible ai algorithms: Issues, purposes, and challenges,” J. Artif. Intell. Res., vol. 71, pp. 1137–1181, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1613/jair.1.12814.

- M. Mattioli and F. Cabitza, “Not in my face: Challenges and ethical considerations in automatic face emotion recognition technology,” Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr., vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 2201–2231, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/make6040109.

- Y. Cui, M. Jia, T.-Y. Lin, Y. Song, and S. Belongie, “Class-balanced loss based on effective number of samples,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 9268–9277, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2019.00949.

- Y. Hong and Y. Chen, “PatchMix: patch-level mixup for data augmentation in convolutional neural networks,” Knowl. Inf. Syst., vol. 66, no. 7, pp. 3855–3881, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10115-024-02141-3.

- X. Zhang, “Multi-modality Medical Image Segmentation with Unsupervised Domain Adaptation,” 2022, https://hdl.handle.net/2123/29776.

- J. Zhang et al., “Badlabel: A robust perspective on evaluating and enhancing label-noise learning,” IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell., vol. 46, no. 6, pp. 4398–4409, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2024.3355425.

- M. Aly, A. Ghallab, and I. S. Fathi, “Enhancing facial expression recognition system in online learning context using efficient deep learning model,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 121419–121433, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3325407.

- G. Zhao, X. Li, Y. Li, and M. Pietikäinen, “Facial micro-expressions: An overview,” Proc. IEEE, vol. 111, no. 10, pp. 1215–1235, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2023.3275192.

- H. Yunusa, S. Qin, A. H. A. Chukkol, A. A. Yusuf, I. Bello, and A. Lawan, “Exploring the synergies of hybrid CNNs and ViTs architectures for computer vision: A survey,” arXiv Prepr. arXiv2402.02941, 2024, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2402.02941.

- C. Liu, K. Hirota, and Y. Dai, “Patch attention convolutional vision transformer for facial expression recognition with occlusion,” Inf. Sci. (Ny)., vol. 619, pp. 781–794, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2022.11.068.

- Y. Li, “Mental Health Management App Interface Design for Women Based on Emotional Equality,” in International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, pp. 368–378, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-61963-2_37.

- A. A. Heydari, C. A. Thompson, and A. Mehmood, “Softadapt: Techniques for adaptive loss weighting of neural networks with multi-part loss functions,” arXiv Prepr. arXiv1912.12355, 2019, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1912.12355.

- J. Chandrasekaran, S. T. Pandeeswari, and S. Pudumalar, “Silos to Synergy: Harnessing Integrated Learning for Improved Outcomes,” J. Eng. Educ. Transform., pp. 318–325, 2024, https://doi.org/10.16920/jeet/2024/v37is2/24056.

- S. Li and W. Deng, “Deep facial expression recognition: A survey,” IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput., vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 1195–1215, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/TAFFC.2020.2981446.

- J.-P. Jiang, S.-Y. Liu, H.-R. Cai, Q. Zhou, and H.-J. Ye, “Representation learning for tabular data: A comprehensive survey,” arXiv Prepr. arXiv2504.16109, 2025, .

- V. W. Anelli, A. Bellogin, T. Di Noia, D. Jannach, and C. Pomo, “Top-n recommendation algorithms: A quest for the state-of-the-art,” in Proceedings of the 30th ACM conference on user modeling, adaptation and personalization, pp. 121–131, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1145/3503252.3531292.

- C. Molnar, G. Casalicchio, and B. Bischl, “Interpretable machine learning--a brief history, state-of-the-art and challenges,” in Joint European conference on machine learning and knowledge discovery in databases, pp. 417–431, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65965-3_28.

- R. Yu and Z. Xu, “Crater-MASN: A Multi-Scale Adaptive Semantic Network for Efficient Crater Detection,” Remote Sens., vol. 17, no. 18, p. 3139, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17183139.

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

Christiany Suwartono is a psychology faculty member at Universitas Katolik Indonesia Atma Jaya, specializing in organizational behavior, management, and psychology. Her research interests focus on leadership development, workplace well-being, and the integration of psychology into business practices. She has published several works in international journals and actively engages in academic collaborations both nationally and internationally. Email: christiany.suwartono@atmajaya.ac.id |

|

Julius Victor Manuel Bata is a lecturer at the Information Systems Department, Universitas Katolik Indonesia Atma Jaya. His academic focus lies in game-based learning, artificial intelligence in games, and the use of computational models to enhance human–computer interaction. He is also involved in projects that bridge education and entertainment technologies, contributing to innovative teaching and learning methodologies. Email: julius.bata@atmajaya.ac.id |

|

Gregorius Airlangga is a lecturer and Program Head of Information Systems at Universitas Katolik Indonesia Atma Jaya. His research interests include artificial intelligence, machine learning, cybersecurity, and autonomous logistics systems, particularly focusing on UAV and USV applications in rural and coastal areas. He has actively published in Scopus-indexed journals and is involved in research collaborations that connect technology, society, and innovation. Email: gregorius.airlangga@atmajaya.ac.id |

Christiany Suwartono (Enhancing Facial Emotion Recognition on FER2013 Using Attention-based CNN and Sparsemax-Driven Class-Balanced Architectures)