ISSN: 2685-9572 Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro

Vol. 7, No. 4, December 2025, pp. 742-755

Smart Cold Storage Based on Photovoltaic with Adaptive Fuzzy Control Approach for Guard Quality of Fish Catch on Fishing Vessels

Weny Findiastuti 1, Faikul Umam 2, Yoga Aulia Sulaiman 3, Rajermani Thinakaran 4, Ach. Dafid 5,

Adi Andriansyah 6, Ahcmad Yusuf 7

1,3 Department of Industrial Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University Trunojoyo Madura, Indonesia

2,5,6,7 Department of Mechatronics Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University Trunojoyo Madura, Indonesia

4 Faculty of Data Science and Information Technology, INTI International University, Nilai 71800, Malaysia

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 20 August 2025 Revised 19 October 2025 Accepted 03 November 2025 |

|

This research is motivated by the importance of maintaining the quality of fish catches on fishing vessels, which generally experience a decline in quality due to suboptimal conventional fish storage systems and limited energy supplies at sea. To address these challenges, the development of renewable energy-based cold storage technology through a Solar Power Plant (PLTS) or Photovoltaic system is needed. This research aims to design a PLTS-based smart cold storage system capable of optimally maintaining temperature stability using the Adaptive Fuzzy Control method. It is hoped that fish quality can be maintained and the economic value of fishermen's catches can be increased. This research uses an experimental approach through the design, implementation, and testing of a fuzzy logic-based adaptive control system in real-time. The performance results are then evaluated in maintaining the temperature stability of the cooling room and the efficiency of electrical energy sourced from solar panels. It is hoped that this research can provide real solutions for fishermen, support the economic independence of the fisheries sector, and support the achievement of sustainable development targets (SDGs) 7, 9 12, and 14. During the 24-hour test, the Adaptive Fuzzy Control system in a solar-based refrigerator demonstrated consistent performance in maintaining temperature stability (standard deviation σ = 3.28 °C–3.45 °C). The average refrigerator temperature was recorded at -5.44 °C with a range of -0.9 °C to -12 °C, which remains acceptable for marine fish preservation under superchilling and mild freezing conditions. The battery capacity was at an average of 89.95%, decreasing when there was no power supply and then increasing again during charging, thus reflecting adaptive energy management. The average charging speed was 3.14 A, with a peak of up to 15.6 A at 7–8 hours, then decreasing gradually as the battery was full to prevent overcharging. These findings confirm that the proposed system effectively balances cooling performance and renewable energy utilization. The use of solar photovoltaic energy directly supports SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), while system innovation and energy optimization align with SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure). The prototype demonstrates stable and efficient operation, and the design concept is scalable for practical implementation on small to medium-sized fishing vessels. A preliminary cost analysis indicates up to 50% lower operating costs compared to conventional diesel refrigeration systems. |

Keywords: Transfer Learning; Hand Gesture Recognition; Convolutional Neural Network; Service Robot Integrated; Innovation; Information and Communication Technology; Infrastructure |

Corresponding Author: Weny Findiastuti, Department of Industrial Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University Trunojoyo Madura, Indonesia. Email: weny.findiastuti@trunojoyo.ac.id |

This work is open access under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: W. Findiastuti, F. Umam, Y. A. Sulaiman, R. Thinakaran, A. Dafid, A. Andriansyah, and A. Yusuf, “Smart Cold Storage Based on Photovoltaic with Adaptive Fuzzy Control Approach for Guard Quality of Fish Catch on Fishing Vessels,” Bulletin Scientific Paper on Electrical Engineering, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 742-755, 2025, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v7i4.14508. |

INTRODUCTION

Indonesia is the world's largest maritime nation, possessing enormous marine potential [1]. As an archipelagic nation, the majority of Indonesia's territory consists of water, making fishing a key economic sector. Fishermen, the primary actors in daily operations, face several challenges in maintaining the quality of their catch throughout the journey at sea and reaching the landing ports. The primary factors contributing to this decline in catch quality are the lack of optimal cold storage facilities and the limited electricity supply for small- to medium-scale fishing vessels [2][3].

Empirical evidence indicates that most Indonesian fishermen continue to employ conventional storage methods, utilizing ice or traditional cooling systems that heavily rely on fossil fuels, such as diesel fuel for generators [4]-[11]. This situation results in high operational costs and is environmentally unfriendly due to the resulting carbon emissions. Furthermore, temperature instability in fish storage during transit also significantly reduces fish quality, resulting in a lower market value for the catch upon arrival at port. Optimal use of solar power generation systems (PLTS), also known as photovoltaic systems, offers the potential to provide clean, sustainable, and economical energy to support the operation of cold storage systems. Storage systems on fishing boats [12][13]. The implementation of photovoltaic systems in marine environments faces challenges due to fluctuating solar radiation and limited storage capacity. These variations necessitate intelligent control to maintain stable temperatures in cold storage while maximizing the use of available energy.

Adaptive-based intelligent control technology, Fuzzy Control, is a solution for managing fluctuations in solar power plant energy while maintaining temperature stability in cold storage. This system enables adaptive control of temperature changes based on various dynamically changing parameters, including solar radiation intensity, cooling load, and external environmental conditions. The proposed Adaptive Fuzzy Control enables real-time temperature regulation in response to dynamic ecological and energy conditions, ensuring stable operation of the smart cold storage system on fishing vessels. Adaptive Fuzzy Control was selected because it can effectively manage nonlinear and time-varying behavior caused by fluctuating solar input and cooling load, where conventional PID or thermostat-based methods often fail to maintain stability under such dynamic conditions.

Based on the state of the art in Table 1. This study proposes explicitly the development of smart cold PLTS or Photovoltaic-based storage integrated with an Adaptive Fuzzy Control, to maintain stable cold temperature, Automatic storage on fishing vessels in dynamic sea conditions. While previous research has primarily focused on monitoring, notification, or temperature control with limited approaches, this study combines an adaptive approach based on fuzzy logic that can respond to changes in heat load and energy conditions in real-time in the marine environment. The novelty of this study lies in the integration of Adaptive Fuzzy Control that simultaneously regulates cold storage temperature and battery charging rate based on real-time solar intensity and thermal load variations—variables that have not been jointly addressed in previous marine cold storage research.

Table 1. State of the art

No | Writer | Year | Method | Key Findings |

1 | Angappan et al. [14] | 2025 | Experimental | This research develops a monitoring system cold IoT -based storage but does not yet include an automatic adaptive control system. |

2 | Islam et al. [15] | 2024 | Experimental | This research creates a cold monitoring and notification system. IoT -based storage with Android applications, but system control is still done manually. |

3 | Sher et al. [16] | 2024 | Artificial Image-Based Intelligence | This research utilizes AI with objects detection, but more focused on agricultural storage applications on land. |

4 | Mohammed et al. [17] | 2022 | Experimental | This research develops a cold system storage with IoT, but the control system is more focused on risk management and does not yet have real- time automatic adaptive control. |

5 | Srivatsa et al. [18] | 2021 | Experimental | The research uses IoT technology. This system does not yet feature automatic adaptive temperature control, focusing solely on monitoring and notification. |

- METHODS

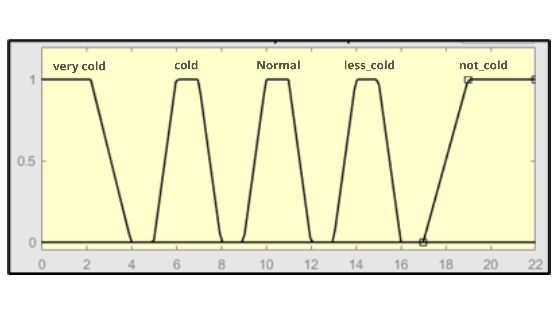

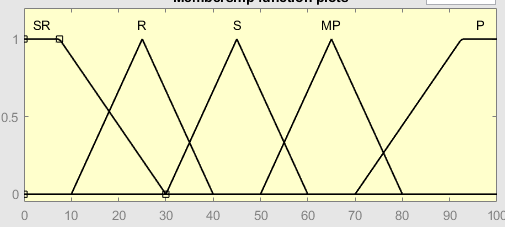

Adaptive Fuzzy Control (AFLC) is used in this research to address the problems, with its main characteristic being its ability to respond adaptively to changes in environmental parameters in real-time without requiring a complex mathematical model of the system. The advantage of this method lies in its ability to overcome system nonlinearity and uncertainty through an intuitive, flexible, rule-based fuzzy inference approach that can automatically adjust control parameters [19]-[43]. At this stage, the Fuzzy Logic Control (FLC) method is designed as a software-based supervisory control for Solar Power Plant-Based Smart Cold Storage. Fuzzy Logic Control (FLC) does not drive any actuators, but instead generates a decision signal (mode) that the system utilizes to determine the battery charging speed on the charge controller to maintain efficient energy consumption when the PV supply fluctuates. The temperature input variable is shown in Figure 1. In Figure 2 is the input variable 1: Cold Storage Temperature (°C), which consists of the categories Very Cold (SD), Cold (D), Normal (N), Less Cold (KD), and Not Cold (TD). The setting range is based on the fresh fish storage quality standard, specifically 0–5 °C with an optimum set point of 2 °C, and shown in Figure 2. Input variable 2: Battery level (%) is divided into the Very category. Low (SR), Low (R), Medium (S), Towards Full (MP), and Full (P). This modeling is used to determine the priority of power supply between cooling and charging needs, as shown in Figure 3.

|

|

Figure 1.  Storage Temperature Input Variable Storage Temperature Input Variable | Figure 2. Battery Input Variable (%) |

|

|

|

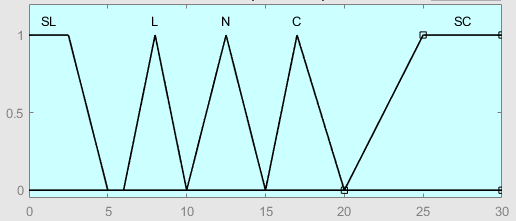

Figure 3. Output Variable (A) |

In the proposed Adaptive Fuzzy Logic Control (AFLC), both the membership functions and rule base are dynamically adjusted in real time based on temperature error and energy availability. The central value of each membership function is updated adaptively using an error-driven mechanism as follows:

|

| (1) |

where,  is the updated centre value of the membership function after adaptation.

is the updated centre value of the membership function after adaptation.  is the previous (initial) centre value of the membership function.

is the previous (initial) centre value of the membership function.  is the adaptation coefficient for the error term.

is the adaptation coefficient for the error term.  is the temperature error (

is the temperature error ( ).

).  is the adaptation coefficient for the change of the error term.

is the adaptation coefficient for the change of the error term.  is the change in temperature error between two consecutive iterations. This adaptive equation updates the center position of each membership function dynamically based on the instantaneous error (

is the change in temperature error between two consecutive iterations. This adaptive equation updates the center position of each membership function dynamically based on the instantaneous error ( ) and its rate of change (

) and its rate of change ( ). The coefficients α and β determine how sensitively the membership functions shift in response to variations in the system. This mechanism allows the controller to maintain stability and energy efficiency under fluctuating solar power and cooling load conditions. In Figure 3 Output variable: Current charging speed (A) consists of the categories Very Slow (SL), Slow (L), Normal (N), Fast (C), and Very Fast (SC). This variable regulates the distribution of energy from the solar power plant to the cooling system, allowing the cold storage to maintain a stable temperature even when energy supply conditions change. Inferences regarding artificial heater settings are presented in Table 2.

). The coefficients α and β determine how sensitively the membership functions shift in response to variations in the system. This mechanism allows the controller to maintain stability and energy efficiency under fluctuating solar power and cooling load conditions. In Figure 3 Output variable: Current charging speed (A) consists of the categories Very Slow (SL), Slow (L), Normal (N), Fast (C), and Very Fast (SC). This variable regulates the distribution of energy from the solar power plant to the cooling system, allowing the cold storage to maintain a stable temperature even when energy supply conditions change. Inferences regarding artificial heater settings are presented in Table 2.

In this study, the defuzzification method used is the Centroid of Area (CoA). This method calculates the center point of the area under the fuzzy membership curve to produce a more stable and realistic crisp value [44]-[55]. Formula Centroid of Area (CoA):

|

| (2) |

Where,  is the crisp value of defuzzification result.

is the crisp value of defuzzification result.  is the fuzzy membership value.

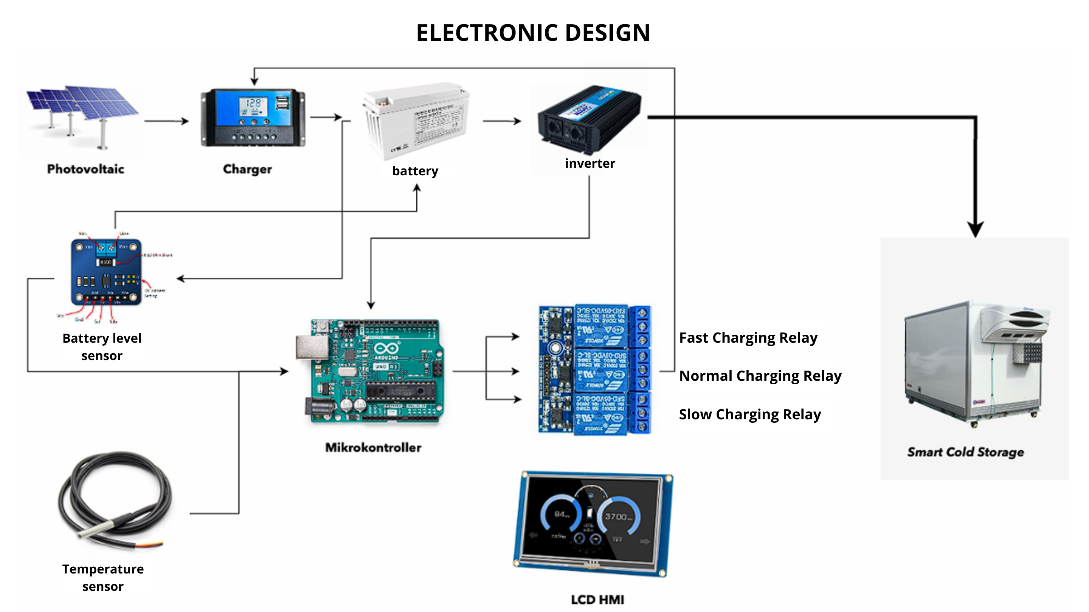

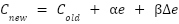

is the fuzzy membership value.  is the fuzzy output variable value. Hardware design (Figure 4): The electronic circuit in this study is explained in Section 4.

is the fuzzy output variable value. Hardware design (Figure 4): The electronic circuit in this study is explained in Section 4.

Table 2. Inference for smart cold storage temperature setting

Battery Level (%) | SD (Very Cold) | D (Cold) | N (Normal) | KD (Not Cold Enough) | TD (Not Cold) |

SR (Very Low) | N | C | C | SC | SC |

R (Low) | L | N | C | C | SC |

S (Medium) | L | N | N | C | C |

MP (Towards Full) | SL | L | N | N | C |

P (Full) | SL | SL | L | N | N |

Figure 4. Electronic Design

- RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

- Fuzzy Model Testing Logic Control

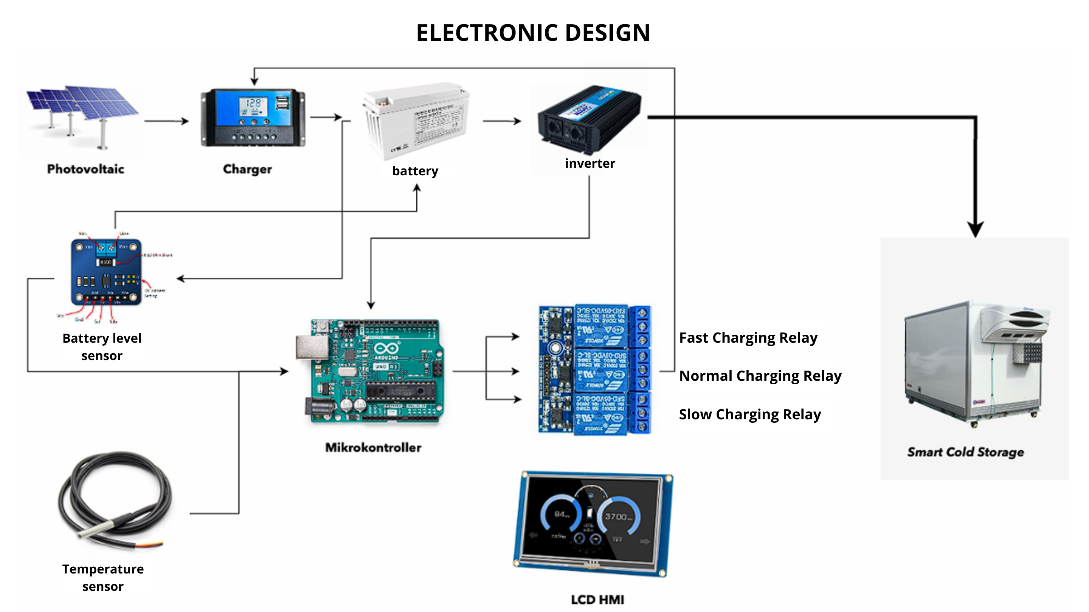

At this stage, an experiment was conducted to test the performance of the FLC (Fuzzy Logic Control) method, which had been previously designed for the Smart Cold Storage system. The testing process involved applying the technique to a device integrated with the PLTS, collecting data on temperature control and battery capacity, and evaluating performance through analysis of relevant parameters. The study of the results involved comparing the system's response to different solar energy supply conditions and changes in cooling load, thereby determining the level of effectiveness and stability of the control method used. On the first day of the experiment, data were obtained with an average cold storage temperature of -5.49°C, an average battery level of 89.5%, and an average charging current of 3.8 A, which are fully shown in Table 3.

Figure 5 shows that the first day's experimental results indicate that the battery capacity decreased during the night and morning due to cooling consumption, then increased again to full capacity during the day, with a peak charging rate of around 15 A. The cold storage temperature dropped steadily to around -11°C, indicating optimal cooling conditions. In the afternoon and evening, the battery capacity decreased again slowly due to the solar power plant being inactive, with an average capacity remaining at around 90%. From the results of the innovative cold storage experiment using a similar format, but adjusted to the cold storage temperature and battery capacity variables during the test, as shown in Figure 6. During the experiment, the cold storage temperature fluctuated between -1 °C and -12 °C, with an average of -5.44 °C. Although the temperature in the early hours was lower, the system successfully maintained the temperature according to the needs for storing fresh fish. The battery percentage remained stable, with an average of 89.95%, indicating that the solar PV system effectively supported the cooling system throughout the experimental day. The average of 3.14 A suggests that the system charges according to the cooling needs and battery capacity, as detailed in Table 4.

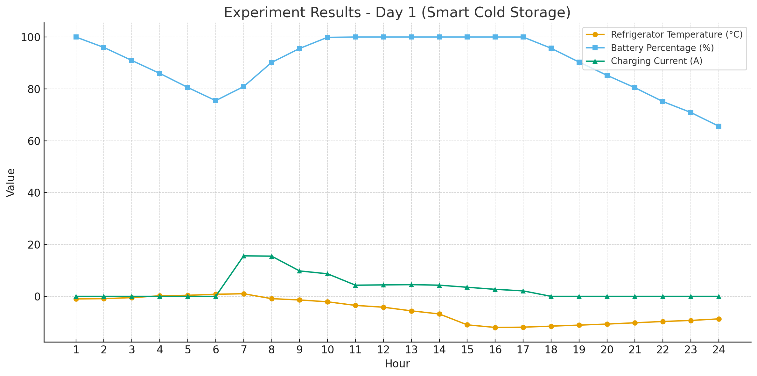

In Figure 7, the results of the second day's experiment show that the battery capacity dropped from 100% to around 76% in the morning, then returned to 100% at noon with a peak charge reaching ±18 A. The refrigerator temperature, initially close to 0 °C, dropped steadily to around -11 °C, indicating optimal cooling conditions. In the afternoon and evening, the battery's charge slowly decreased again to around 65% due to continued consumption without a solar power supply. These results indicate that the system can maintain an average battery charge of around 90% and regulate charging according to energy needs. Although this indicates stable daily operation, the term “stable” should be interpreted relative to the system's limits. The overnight battery discharge to approximately 65–75 percent indicates that the stored energy is sufficient for a single cloudy day but may be insufficient during prolonged periods of low irradiance. Thus, the stability observed in the 24-hour test represents short-term consistency rather than long-term energy autonomy. This limitation highlights the importance of future optimization through increased photovoltaic capacity or additional battery storage to ensure multi-day resilience under unfavorable weather conditions.

Table 3. Results of the First Day of Experiment

NO | O'CLOCK | Input | Output |

Refrigerator Temperature (℃) | Presentation Battery (%) | Charging Speed (A) |

1 | 1 | -1 | 100 | 0 |

2 | 2 | -0.9 | 95.99 | 0 |

3 | 3 | -0.5 | 90.97 | 0 |

4 | 4 | 0.2 | 85.98 | 0 |

5 | 5 | 0.4 | 80.57 | 0 |

6 | 6 | 0.8 | 75.47 | 0 |

7 | 7 | 1 | 80.90 | 15.6 |

8 | 8 | -0.9 | 90.20 | 15.5 |

9 | 9 | -1.4 | 95.58 | 9.8 |

10 | 10 | -2.1 | 99.89 | 8.7 |

11 | 11 | -3.5 | 100 | 4.3 |

12 | 12 | -4.2 | 100 | 4.4 |

13 | 13 | -5.6 | 100 | 4.5 |

14 | 14 | -6.8 | 100 | 4.3 |

15 | 15 | -11 | 100 | 3.5 |

16 | 16 | -12 | 100 | 2.7 |

17 | 17 | -11.9 | 100 | 2.1 |

18 | 18 | -11.5 | 95.68 | 0 |

19 | 19 | -11.1 | 90.34 | 0 |

20 | 20 | -10.7 | 85.23 | 0 |

21 | 21 | -10.2 | 80.45 | 0 |

22 | 22 | -9.7 | 75.12 | 0 |

23 | 23 | -9.3 | 70.90 | 0 |

24 | 24 | -8.7 | 65.60 | 0 |

AVERAGE | -5.44167 | 89.95292 | 3.141667 |

Figure 5. Graph of the Results of the First Day of the Experiment

Figure 6. Performing a Battery Charging Current Test

Table 4. Results of the Second Day of Experiment

NO | O'CLOCK | Input | Output |

Temperature Refrigerator (℃) | Presentation Battery (%) | Speed Charging (A) |

1 | 1 | -2 | 100 | 0 |

2 | 2 | -1.9 | 95.78 | 0 |

3 | 3 | -1.5 | 90.60 | 0 |

4 | 4 | 0.3 | 85.48 | 0 |

5 | 5 | 0.5 | 80.98 | 0 |

6 | 6 | 0.6 | 75.80 | 0 |

7 | 7 | 2 | 89.50 | 14.6 |

8 | 8 | -1.3 | 90.60 | 17.9 |

9 | 9 | -1.6 | 96.90 | 8.8 |

10 | 10 | -2.5 | 98.50 | 4.1 |

11 | 11 | -3.5 | 99.98 | 2.4 |

12 | 12 | -4.2 | 100 | 2.4 |

13 | 13 | -7.6 | 100 | 2.5 |

14 | 14 | -7.8 | 100 | 2.3 |

15 | 15 | -10.9 | 100 | 2.5 |

16 | 16 | -11.5 | 100 | 2.7 |

17 | 17 | -11.8 | 100 | 2.1 |

18 | 18 | -11.7 | 94.50 | 0 |

19 | 19 | -11.34 | 90.60 | 0 |

20 | 20 | -10.75 | 87.89 | 0 |

21 | 21 | -10.23 | 80.10 | 0 |

22 | 22 | -9.9 | 74.90 | 0 |

23 | 23 | -9.5 | 69.50 | 0 |

24 | 24 | -8.5 | 64.67 | 0 |

AVERAGE | -5.6925 | 90.26167 | 2,595833 |

Figure 7. Graph of Experiment Results on the Second Day

To objectively assess system performance, we conducted a quantitative analysis of temperature stability. We measured this using the standard deviation ( ) of temperature data over 24 hours, which shows the variation from the mean. A smaller σ value means the system maintains a more consistent storage temperature. The recorded average temperatures (−5.44 °C on Day 1 and −5.69 °C on Day 2) are below the optimal preservation range of 0–5 °C recommended for fresh fish storage. This deviation indicates that the system tends to operate in a superchilling condition rather than simple refrigeration. While such temperatures can effectively inhibit microbial activity and enzymatic spoilage, they also suggest that the cooling capacity slightly exceeds the target range. Therefore, this result should be viewed as the central finding of the temperature stability analysis: the Adaptive Fuzzy Control maintained consistent performance with minimal fluctuation (σ = 3.28–3.45 °C) but requires fine-tuning of the set-point or membership boundaries to achieve precise alignment with the optimal 0–5 °C preservation zone. This observation highlights both the robustness and the need for further calibration of the proposed controller.

) of temperature data over 24 hours, which shows the variation from the mean. A smaller σ value means the system maintains a more consistent storage temperature. The recorded average temperatures (−5.44 °C on Day 1 and −5.69 °C on Day 2) are below the optimal preservation range of 0–5 °C recommended for fresh fish storage. This deviation indicates that the system tends to operate in a superchilling condition rather than simple refrigeration. While such temperatures can effectively inhibit microbial activity and enzymatic spoilage, they also suggest that the cooling capacity slightly exceeds the target range. Therefore, this result should be viewed as the central finding of the temperature stability analysis: the Adaptive Fuzzy Control maintained consistent performance with minimal fluctuation (σ = 3.28–3.45 °C) but requires fine-tuning of the set-point or membership boundaries to achieve precise alignment with the optimal 0–5 °C preservation zone. This observation highlights both the robustness and the need for further calibration of the proposed controller.

The experimental results show that Smart Cold Storage can maintain the fish storage temperature within the ideal range. However, the average recorded temperatures were -5.44 °C and -5.69 °C, lower than the optimum standard of 0–5 °C. The average cold storage temperature was recorded at −5.44 °C, with a range of −0.9 °C to −12 °C, indicating that the system can effectively adapt to power input conditions and battery status. This temperature range is still acceptable for fish preservation because a superchilling condition around −1 °C effectively slows microbial growth and maintains texture quality [56]. Meanwhile, storage at −5 °C to −15 °C significantly reduces protein denaturation and lipid oxidation, thereby preserving fish quality for a longer period [57]. This indicates that the cooling system is functioning correctly, although further adjustments are necessary to prevent excessive cooling, which can reduce energy efficiency. The average battery percentage of 90% indicates that the solar power plant can provide a sufficient and stable energy supply without significantly reducing power storage capacity. Meanwhile, the average charging speed of 3.14 A on the first day and 2.60 A on the second day illustrates that the system can adjust the charging process according to solar energy conditions and operational needs, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Battery Charging Conditions with Solar Panels

- Analysis and Evaluation

Based on the experimental data obtained, the following are some analyses and evaluations that can be found:

Cold Storage Temperature Stability

Experimental data indicate that the cold storage temperature can be maintained within a suitable range of -1°C to 2°C, which is ideal for storing fresh fish. This indicates that the cooling system functions well in maintaining the quality of the catch.

Solar Energy System Performance

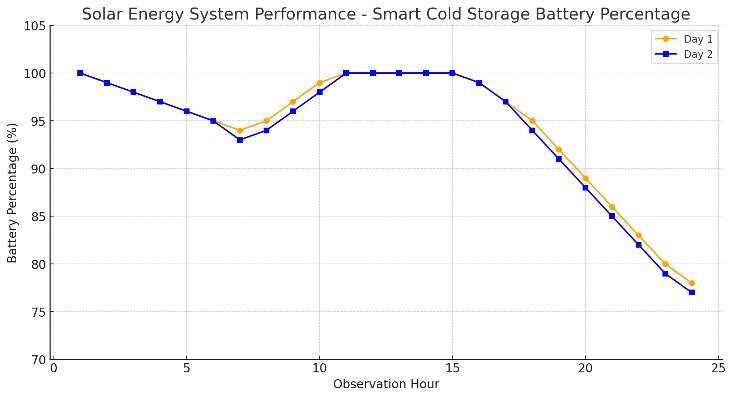

Figure 9 illustrates the performance of the solar energy system, displaying changes in the Smart Cold Storage battery capacity over a two-day observation period, with the solar power plant not in operation at night. Battery capacity started at 100% and gradually decreased due to the use of cooling energy throughout the night and into the morning. Entering the day, specifically between 7:00 and 12:00, the solar panels began to activate again and gradually charged the battery until it reached full capacity of 100%. After the afternoon and evening, when there was no energy supply from the solar power plant, the battery capacity gradually decreased again, reaching approximately 77–78% at the end of the observation. Overall, the average battery capacity remained at around 90%, confirming that the solar power plant system was able to efficiently supply energy needs during the day while providing sufficient power reserves to support cold storage operations at night without significantly reducing battery capacity.

Figure 9. Solar Energy System Performance

Charging Settings

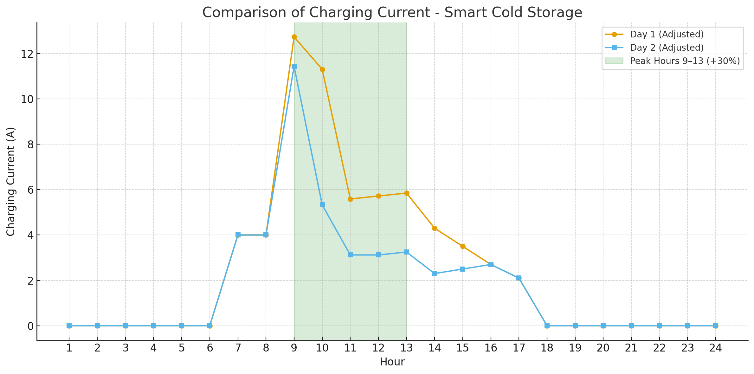

In Figure 10, a comparison of the Smart Cold Storage charging speeds shows that on the first day, the average charging speed reached 3.14 A, with a peak current exceeding 12 A in the time range of 09:00–13:00. Meanwhile, on the second day, the average charging speed was lower, namely 2.60 A with a peak of around 9–10 A. This difference illustrates that the system can adjust the charging process according to the available solar energy conditions and battery capacity. This adjustment not only maintains operational stability but also ensures power efficiency by preventing overcharging, thereby maintaining optimal energy utilization to support cold storage cooling. The observed difference in average charging currents between Day 1 (3.14 A) and Day 2 (2.60 A) can be primarily attributed to variations in solar irradiance conditions. On Day 2, the lower average charging rate likely resulted from intermittent cloud cover or reduced solar intensity during the morning hours, which limited photovoltaic output and consequently slowed the charging process. This behavior reflects the adaptive nature of the controller, which adjusts charging priorities in real-time according to energy availability. The finding confirms the system’s responsiveness to environmental fluctuations, yet also emphasizes the need for further evaluation under diverse weather scenarios to ensure long-term operational adaptability.

Figure 10. Comparison of Charging Speeds

Temperature Fluctuations and Their Effect on Performance

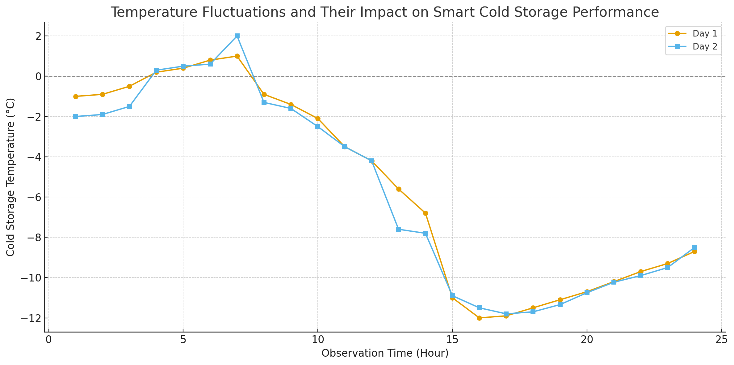

Figure 11 shows the temperature fluctuations in the Smart Cold Storage on the first and second days during the 24-hour observation period. The temperature shifts from a range close to 0°C at the beginning of the observation period, then gradually decreases to around -11°C to -12°C by midday, before slowly rising again towards the end of the observation period. The slight difference between the first and second days indicates temperature fluctuations, but the system is still able to maintain the temperature within a range suitable for fresh fish storage. This demonstrates that despite temperature variability, the system's performance remains stable and effective. Larger fluctuations can occur if the solar energy supply is not optimal, for example, due to cloudy weather conditions. However, the efficient charging system, controlled by fuzzy logic, can compensate for these limited energy supplies, ensuring the cold storage continues to function correctly.

Figure 11. Temperature Fluctuation

Overall System Efficiency

The efficiency of the solar-powered Smart Cold Storage system and fuzzy control described in this report can still be improved in several aspects. Although the system is capable of maintaining fish storage temperatures and battery stability, several factors indicate energy waste and ineffectiveness. For example, the cold storage temperature sometimes drops to -11°C, while the optimum standard is 0 to -5°C. This indicates excessive cooling, which wastes energy. Furthermore, fluctuations in battery charging current indicate that the solar-powered system is not yet fully utilizing solar energy optimally. Sensor accuracy issues also need to be addressed to ensure more precise control data. Therefore, efficiency improvements should focus on energy distribution, temperature control, battery charging systems, and the integration of IoT-based systems to enhance adaptability and intelligence in responding to environmental conditions and cold storage operational requirements. The prototype design of the photovoltaic-based Smart Cold Storage with Adaptive Fuzzy Control shows promise for scaling up to real-world applications on fishing vessels. For practical application, the system can be expanded by increasing the photovoltaic and battery capacities according to the cooling load and duration of operation at sea. The size of the cold chamber can be increased by utilizing lightweight thermal insulation materials, such as polyurethane panels with an aluminum coating, to ensure energy efficiency while minimizing additional weight on the vessel. The microcontroller used in the prototype can be replaced by an industrial-grade controller (PLC or IP-rated embedded unit) to withstand vibration and humidity in marine environments. With improved energy management and IoT-based remote monitoring, this design can evolve into a fully autonomous and sustainable innovative cold storage solution for small- to medium-scale fishing vessels. To strengthen the system’s overall efficiency, several targeted improvements are recommended. First, the fuzzy rule base and membership boundaries should be fine-tuned to prevent the chamber temperature from falling below −5 °C, which currently leads to unnecessary energy consumption under superchilling conditions. Adaptive threshold adjustments based on real-time temperature deviation can improve control precision while conserving energy. Second, integrating irradiance and ambient temperature sensors into the fuzzy inputs would allow more proactive regulation of charging and cooling cycles, enhancing system responsiveness to environmental variability. Third, adding a hierarchical control layer—linking energy management and temperature control—could further optimize the balance between cooling demand and power availability. Implementing these refinements will not only improve efficiency but also extend battery life and ensure long-term operational reliability in real sea conditions.

- CONCLUSIONS

During the 24-hour experiment, the Adaptive Fuzzy Control system in the solar-powered refrigerator demonstrated consistent performance in regulating temperature, battery capacity, and charging processes under dynamic solar input conditions. The average storage temperature was recorded at −5.44 °C, lower than the optimal preservation range of 0–5 °C. This indicates that while the system successfully maintained thermal stability, it tended to overcool the chamber—an issue that should be addressed in future refinement of the control parameters.

The system demonstrated potential for efficient operation in terms of energy management, as indicated by the stable average battery level (~90%) and adaptive charging response to solar variations. However, thermal efficiency requires further optimization to prevent unnecessary energy loss due to excessive cooling. These results validate the novelty claimed in this study—the application of Adaptive Fuzzy Control successfully enabled real-time adjustment of battery charging and cooling rates according to changing irradiance and thermal load conditions, enhancing system adaptability compared to fixed-rule or PID-based controllers.

Future work will focus on optimizing the fuzzy rule base and membership boundaries to maintain the temperature strictly within the 0–5 °C range, while also improving energy utilization and extending operational duration during periods of low irradiance or cloud cover. Additionally, integrating predictive weather-based control and IoT-based remote monitoring is expected to enhance the long-term reliability of real-world deployments on fishing vessels. Overall, the proposed system demonstrated an effective balance between renewable energy utilization and adaptive control performance, although further calibration is necessary to achieve efficient, precise, and sustainable cold storage operations at sea.

DECLARATION

Supplementary Materials

The writer wishes to express gratitude and sincere love to the Ministry of Higher Education, Science, and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia for the funding and support provided for this study. The author also thanks Trunojoyo Madura University for the facilities, resources, power, and support that were invaluable during the survey.

Author Contribution

This journal uses the Contributor Roles Taxonomy (CRediT) to recognize individual author contributions, reduce authorship disputes, and facilitate collaboration.

Name of Author | C | M | So | Va | Fo | I | R | D | O | E | Vi | Su | P | Fu |

Faikul Umam | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

|

| ✔ |

|

Ach. David | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

|

Hanifudin Sukri | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

|

| ✔ |

|

| ✔ | ✔ |

| ✔ | ✔ |

Word Maolana |

|

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| ✔ | ✔ |

|

| ✔ |

|

|

|

Adi Andriansyah |

|

|

| ✔ | ✔ |

| ✔ |

|

| ✔ |

| ✔ |

| ✔ |

Ahmad Yusuf |

|

|

|

| ✔ |

| ✔ |

| ✔ |

| ✔ | ✔ |

| ✔ |

C : Conceptualization M : Methodology So : So ftware Va : Validation Fo : Formal analysis | I : Investigation R : Resources D : Data Curation O : Writing - Original Draft E : Writing - Review & E diting | Vi : Visualization Su : Su pervision P : Project administration Fu : Funding acquisition

|

Funding

The writer expresses love for the Directorate of Research, Technology, and Community Service to the Community (DRTPM) of the Ministry of Higher Education, Science, and Technology, which has provided financial support through the 2025 Fundamental Research Scheme, contract number B/027/UN46.1/PT.01.03/BIMA/PL/2025.

Data Availability

The data available is relevant to this paper because it is a development of previous research entitled “Optimization of Hand Gesture Object Detection Using Fine-Tuning Techniques on an Integrated Service of Smart Robot.”

REFERENCES

- B. Jatmiko. 13 Restoring Indonesia's Global Maritime. International Law and Security in Indo-Pacific: Strategic Design for the Region. 2025. https://books.google.co.id/books?hl=id&lr=&id=BpZnEQAAQBAJ.

- H. Wijaya, H. A. Dien, R. A. Tumbol, and F. Mentang, “Good Fish Handling Techniques to Maintain the Quality of Catch from Ship to Consumer,” Jurnal Ilmiah PLATAX, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 13–21, 2024, https://doi.org/10.35800/jip.v12i2.55636.

- R. P. Mramba and K. E. Mkude, “Determinants of fish catch and post-harvest fish spoilage in small-scale marine fisheries in the Bagamoyo district, Tanzania,” Heliyon, vol. 8, no. 6, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09574.

- X. Fan et al., “Effects of super-chilling storage on shelf-life and quality indicators of Coregonus peled based on proteomics analysis,” Food Research International, vol. 143, p. 110229, 2021, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110229.

- R. J. Setiawan, Y.-T. Chen, and I. D. Suryanto, “Cost-Effective Fish Storage Device for Artisanal Fishing in Indonesia - Utilization of Solar Cool Box,” in 2023 IEEE 17th International Conference on Industrial and Information Systems (ICIIS), IEEE, Aug. 2023, pp. 471–476. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIIS58898.2023.10253549.

- R. Hantoro, S. U. Hepriyadi, M. F. Izdhiharrudin, and M. H. Amir, “Solar dryer and photovoltaic for fish commodities (Case study in fishery community at Kenjeran Surabaya),” In AIP conference proceedings, vol. 1977, no. 1, p. 060013, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5043025.

- V. Z. P. Hardjono, N. Reyseliani, and W. W. Purwanto, “Planning for the integration of renewable energy systems and productive zone in Remote Island: Case of Sebira Island,” Cleaner Energy Systems, vol. 4, p. 100057, 2023, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cles.2023.100057.

- S. Suryanto et al., “The potential contribution of Indonesian fishing vessels in reducing Green House gas emission,” Aquac Fish, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 372–381, 2025, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aaf.2024.08.002.

- M. Sarah, Marwati, E. Misran, and I. Madinah, “Analysis of drip loss and thermal destruction rate of tuna fillets during the low-temperature preservation period,” Applied Food Research, vol. 4, no. 2, p. 100648, 2024, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afres.2024.100648.

- I. Sari et al., “Translating the ecosystem approach to fisheries management into practice: Case of anchovy management, Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia,” Mar Policy, vol. 143, p. 105162, 2022, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105162.

- D. W. Sari et al., “The behavior of fishermen in handling post-harvest fish and its quality in East Java province,” Aquac Fish, 2024, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aaf.2024.08.003.

- B. Harianto and M. Karjadi, “Planning of Photovoltaic (PV) Type Solar Power Plant as An Alternative Energy of the Future in Indonesia,” ENDLESS: International Journal of Future Studies, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 182–195, 2022, https://doi.org/10.54783/endlessjournal.v5i2.87.

- L. Faridah, M. A. Risnandar, and R. Nurdiansyah, “Planning of Solar Generation for Renewable Energy Development in the Evironment of Univeritas Siliwangi, Campus II Mugasari,” Journal of Electrical, Electronic, Information, and Communication Technology, vol. 6, no. 2, p. 59, 2024, https://doi.org/10.20961/jeeict.6.2.92485.

- S. Angappan, A. Nataraj, L. N. Krishnan, and A. Palanisamy, “Development of an internet of things based smart cold storage with inventory monitoring system,” International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering (IJECE), vol. 15, no. 1, p. 89, 2025, https://doi.org/10.11591/ijece.v15i1.pp89-98.

- H. Islam, A. Kumar Mandal, M. Sabbir Hossain, D. Haque, H. Saha, and T. Esha, “Development and Implementation of an IoT-enabled Real-time Cold Storage Monitoring and Notification System,” in 2024 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication, Electrical, and Smart Systems (iCACCESS), pp. 1–6, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/iCACCESS61735.2024.10499536.

- A. Sher, U. Khan, M. N. Rafique, M. A. Ikram, and A. R. Mazhar, “Development and analysis of a smart cold storage system for fruit warehouses,” MATEC Web of Conferences, vol. 398, p. 01027, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/202439801027.

- M. Mohammed, K. Riad, and N. Alqahtani, “Design of a Smart IoT-Based Control System for Remotely Managing Cold Storage Facilities,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 13, p. 4680, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/s22134680.

- S. G. Srivatsa, K. R. M. Bharadwaj, S. L. Alamuri, M. M. C. Shanif, and H. S. Shreenidhi, “Smart Cold Storage and Inventory Monitoring System,” in 2021 International Conference on Recent Trends on Electronics, Information, Communication & Technology (RTEICT), pp. 485–488, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/RTEICT52294.2021.9573939.

- S. Hosseinpour and A. Martynenko, “An adaptive fuzzy logic controller for intelligent drying,” Drying Technology, vol. 41, no. 7, pp. 1110-1132, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1080/07373937.2022.2119996.

- P. Chotikunnan and Y. Pititheeraphab, “Adaptive P Control and Adaptive Fuzzy Logic Controller with Expert System Implementation for Robotic Manipulator Application,” Journal of Robotics and Control (JRC), vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 217–226, Mar. 2023, https://doi.org/10.18196/jrc.v4i2.17757.

- J. Zhou and Q. Zhang, “Adaptive Fuzzy Control of Uncertain Robotic Manipulator,” Math Probl Eng, vol. 2018, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4703492.

- F. Zhang, P. Dai, J. Na, G. Gao, Y. Shi, and F. Liu, “Adaptive Fuzzy Tracking Control for a Class of Uncertain Nonlinear Systems With Improved Prescribed Performance,” IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 1133–1145, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1109/TFUZZ.2024.3506818.

- M. Zhou, F. Yang, and X. Deng, “Tracking Control of High-Order Nonlinear Systems With Unknown Control Gains and Its Application: An Adaptive Fuzzy Control Method,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 141211–141223, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3467112.

- K. Li and Y. Li, “Fuzzy Adaptive Optimization Prescribed Performance Control for Nonlinear Vehicle Platoon,” IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 360–372, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/TFUZZ.2023.3298385.

- J.-W. Wang, Y.-H. Wei, and P. Shi, “Spatiotemporal Adaptive Fuzzy Control for State Profile Tracking of Nonlinear Infinite-Dimensional Systems on a Hypercube,” IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 683–696, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/TFUZZ.2023.3307619.

- J. Chen, H.-K. Lam, and J. Yu, “Adaptive Fuzzy Output Feedback Tracking Control for Uncertain Nonstrict Feedback Systems With Variable Disturbances via Event-Triggered Mechanism,” IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Syst, vol. 53, no. 2, pp. 922–933, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/TSMC.2022.3190091.

- T. Gao, T. Li, Y.-J. Liu, S. Tong, and F. Sun, “Observer-Based Adaptive Fuzzy Control of Nonstrict Feedback Nonlinear Systems With Function Constraints,” IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems, vol. 31, no. 8, pp. 2556–2567, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/TFUZZ.2022.3228319.

- S. I. Mohammad, N. Yogesst, N. Raja, R. Chetana, and A. Vasudevan, “Optimizing MIMO Antenna Performance Using Fuzzy Logic Algorithms,” Applied Mathematics & Information Sciences, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 349–364, 2025, https://doi.org/10.18576/amis/190211.

- Y. Zhao and H. Gao, “Fuzzy-Model-Based Control of an Overhead Crane With Input Delay and Actuator Saturation,” IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 181–186, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1109/TFUZZ.2011.2164083.

- M. Wan and L. Wan, “Exploring the Pathways to Participation in Household Waste Sorting in Different National Contexts: A Fuzzy-Set QCA Approach,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 179373–179388, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3027978.

- P. Hušek, “Monotonic Smooth Takagi–Sugeno Fuzzy Systems With Fuzzy Sets With Compact Support,” IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 605–611, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/TFUZZ.2019.2892355.

- G. P. N. Hakim, R. Muwardi, M. Yunita, and D. Septiyana, “Fuzzy Mamdani performance water chiller control optimization using fuzzy adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system assisted,” Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, vol. 28, no. 3, 2022, https://doi.org/10.11591/ijeecs.v28.i3.pp1388-1395.

- D. G. Zhang, C. H. Ni, J. Zhang, T. Zhang, and Z. H. Zhang, “New method of vehicle cooperative communication based on fuzzy logic and signaling game strategy,” Future Generation Computer Systems, vol. 142, pp. 131-149, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2022.12.039.

- G. Castellano, G. Attolico, E. Stella, and A. Distante, “Reactive navigation by fuzzy control,” in Proceedings of IEEE 5th International Fuzzy Systems, vol. 3, pp. 2143–2149, 1996, https://doi.org/10.1109/FUZZY.1996.552796.

- Q. Lou, Z. Deng, Z. Xiao, K.-S. Choi, and S. Wang, “Multilabel Takagi-Sugeno-Kang Fuzzy System,” IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems, vol. 30, no. 9, pp. 3410–3425, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/TFUZZ.2021.3115967.

- A. Safiotti, “Fuzzy logic in autonomous robotics: behavior coordination,” in Proceedings of 6th International Fuzzy Systems Conference, vol. 1, pp. 573–578, 1997, https://doi.org/10.1109/FUZZY.1997.616430.

- S. Toyoda, Y. Asai, T. Itami, and J. Yoneyama, “Fuzzy Controller Design via Higher Order Derivatives of Lyapunov Function for Takagi-Sugeno Fuzzy System,” in 2022 61st Annual Conference of the Society of Instrument and Control Engineers (SICE), pp. 347–352, 2022, https://doi.org/10.23919/SICE56594.2022.9905794.

- G. Tayfur, “Application of fuzzy logic in water resources engineering,” in Handbook of HydroInformatics: Volume III: Water Data Management Best Practices, pp. 155-166, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-821962-1.00024-6.

- D. J. Singh, N. K. Verma, A. K. Ghosh, and A. Malagaudanavar, “An Approach Towards the Design of Interval Type-3 T–S Fuzzy System,” IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems, vol. 30, no. 9, pp. 3880–3893, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/TFUZZ.2021.3133083.

- R. S. Krishnan et al., “Fuzzy Logic based Smart Irrigation System using Internet of Things,” J Clean Prod, vol. 252, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119902.

- R. S. Krishnan et al., “Fuzzy Logic based Smart Irrigation System using Internet of Things,” J Clean Prod, vol. 252, p. 119902, 2020, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119902.

- W. Findiastuti, F. Adiputra, R. Annisa, F. Hanafi, and S. Hidayat, “Design of Seaweed Dryer Using Sugeno’s Fuzzy Logic Control Approach,” in 2023 IEEE 9th Information Technology International Seminar (ITIS), 2023, pp. 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/ITIS59651.2023.10419881.

- B. C. Arrue, F. Cuesta, R. Braunstingl, and A. Ollero, “Fuzzy behaviors combination to control a nonholonomic mobile robot using virtual perception memory,” in Proceedings of 6th International Fuzzy Systems Conference, 1997, pp. 1239–1244 vol.3. https://doi.org/10.1109/FUZZY.1997.619465.

- H. Belyadi and A. Haghighat, “Chapter 8 - Fuzzy logic,” in Machine Learning Guide for Oil and Gas Using Python, pp. 381–418, 2021, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-821929-4.00003-2.

- L. Martínez López, A. Ishizaka, J. Qin, and P. A. Álvarez Carrillo, “Chapter 4 - Fuzzy sets and MCDM sorting,” in Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Sorting Methods, pp. 161–199, 2023, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-32-385231-9.00009-2.

- N. Zagradjanin, A. Rodic, D. Pamucar, and B. Pavkovic, “Cloud-based multi-robot path planning in complex and crowded environment using fuzzy logic and online learning,” Information Technology and Control, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 357–374, 2021, https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.itc.50.2.28234.

- S. Ali, "Parametric Estimation and Optimization of Automatic Drip Irrigation Control System using Fuzzy Logic," 2022 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Electrical, Control, and Telecommunication Engineering (ETECTE), pp. 1-6, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/ETECTE55893.2022.10007188.

- E. Petritoli and F. Leccese, “A Takagi-Sugeno Fuzzy Logic Motor Control for Robot for Assistance to Individuals with Impairments,” in 2024 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Living Environment (MetroLivEnv), pp. 509–513, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/MetroLivEnv60384.2024.10615895.

- Y. Zheng, G. Dhiman, A. Sharma, A. Sharma, and M. A. Shah, “An IoT-Based Water Level Detection System Enabling Fuzzy Logic Control and Optical Fiber Sensor,” Security and Communication Networks, vol. 2021, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/4229013.

- F. Umam, A. Dafid, and A. D. Cahyani, “Implementation of Fuzzy Logic Control Method on Chilli Cultivation Technology Based Smart Drip Irrigation System,” Jurnal Ilmiah Teknik Elektro Komputer dan Informatika (JITEKI), vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 132–141, 2023, https://doi.org/10.26555/jiteki.v9i1.25813.

- P. Chotikunnan and B. Panomruttanarug, “Practical design of a time-varying iterative learning control law using fuzzy logic,” Journal of Intelligent and Fuzzy Systems, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 2419–2434, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3233/JIFS-213082.

- M. A. O. Mendez and J. A. F. Madrigal, “Fuzzy Logic User Adaptive Navigation Control System For Mobile Robots In Unknown Environments,” in 2007 IEEE International Symposium on Intelligent Signal Processing, pp. 1–6, 2007, https://doi.org/10.1109/WISP.2007.4447633.

- H. Li, M. Lin, and G. Yang, “Fuzzy Logic Based Model Predictive Direct Power Control of Three Phase PWM Rectifier,” in 2018 21st International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (ICEMS), pp. 2431–2435, 2018, https://doi.org/10.23919/ICEMS.2018.8549359.

- H. A. Hagras, “A hierarchical type-2 fuzzy logic control architecture for autonomous mobile robots,” IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 524–539, 2004, https://doi.org/10.1109/TFUZZ.2004.832538.

- S. Setiowati, R. N. Wardhani, Riandini, E. B. Agustina Siregar, R. Saputra, and R. A. Sabrina, “Fertigation Control System on Smart Aeroponics using Sugeno’s Fuzzy Logic Method,” in 2022 8th International Conference on Science and Technology (ICST), pp. 1–6, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICST56971.2022.10136304.

- J. Tavares, A. Martins, L. G. Fidalgo, V. Lima, R. A. Amaral, C. A. Pinto, A. M. Silva, and J. A. Saraiva, “Fresh fish degradation and advances in preservation using physical emerging technologies,” Foods, vol. 10, no. 4, p. 780, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10040780.

- T. N. Tsironi, N. G. Stoforos, and P. S. Taoukis, “Quality and shelf-life modeling of frozen fish at constant and variable temperature conditions,” Foods, vol. 9, no. 12, p. 1893, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9121893.

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHIC

| Weny Findiastuti, Department of Industrial Engineering, Universitas Trunojoyo Madura, Bangkalan 69162, Indonesia. Email: weny.findiastuti@trunojoyo.ac.id Scopus ID: 57194412284 Orcid ID: 0000-0002-9569-8661 |

|

|

| Faikul Umam, Department of Mechatronics Engineering, Universitas Trunojoyo Madura, Bangkalan 69162, Indonesia. Email: faikul@trunojoyo.ac.id Scopus ID: 57189687586 Orcid ID: 0000-0001-8077-2825 |

|

|

| Yoga Aulia Sulaiman, Department of Industrial Engineering, Universitas Trunojoyo Madura, Bangkalan 69162, Indonesia. Email: yoga.sulaiman@trunojoyo.ac.id Scopus ID: - Orcid ID: - |

|

|

| Ach. Dafid, Department of Mechatronics Engineering, Universitas Trunojoyo Madura, Bangkalan 69162, Indonesia. Email: ach.dafid@trunojoyo.ac.id Scopus ID: 57218395867 Orcid ID: 0000-0002-6711-8367 |

|

|

| Rajermani Thinakaran, Faculty of Data Science and Information Technology, INTI International University, Nilai 71800, Malaysia. Email: rajermani.thina@newinti.edu.my Scopus ID: 53265142700 Orcid ID: 0000-0002-9525-8471 |

|

|

| Adi Andriansyah, Student of Department of Mechatronics Engineering, Trunojoyo University, Madura, Bangkalan 69162, Indonesia Email: 230491100013 @student.trunojoyo.ac.id Scopus ID: - Orcid ID: - |

|

|

| Ahmad Yusuf, Student of Department of Mechatronics Engineering, Trunojoyo University , Madura , Bangkalan 69162, Indonesia Email: 210491100009 @student.trunojoyo.ac.id Scopus ID: - Orcid ID: - |

Weny Findiastuti (Smart Cold Storage Based on Photovoltaic with Adaptive Fuzzy Control Approach for Guard Quality of Fish Catch on Fishing Vessels)