ISSN: 2685-9572 Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro

Vol. 8, No. 1, February 2026, pp. 129-140

Optimization of DC Fast Charging in CHAdeMO Systems Using Thunderstorm Algorithm with Thermal and Health Constraints

Samsurizal 1,2, Arif Nur Afandi 1, Mohamad Rodhi Faiz 1

1 Department of Electrical Engineering and Informatics, Universitas Negeri Malang, Malang, Indonesia

2 Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Renewable Energy, Institut Teknologi PLN, Jakarta, Indonesia

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 20 August 2025 Revised 30 December 2025 Accepted 27 January 2026 |

|

The significant increase in the use of electric vehicles (EVs) demands the development of fast charging systems that are not only efficient but also maintain battery integrity. One of the primary challenges in direct current (DC) charging is balancing speed with minimizing degradation caused by thermal stress. This study proposes a charging optimization model based on the Thunderstorm Optimization Algorithm (TA) for CHAdeMO-based DC systems. A lithium-ion equivalent circuit battery model was used to simulate electrochemical and thermal dynamics. The model introduces an adaptive charging current profile designed with a dynamic boundary configuration, defined here as the iterative adjustment of current limits according to real-time thermal and health constraints. Compared to conventional constant current–constant voltage (CC–CV) methods, TA considers maximum temperature, State of Health (SoH), and target State of Charge (SoC) simultaneously. The simulation (180 minutes, passive cooling, Python-based) showed that TA reduced SoH degradation to 1.3% and battery life usage to 18.4%—the latter defined as cumulative stress energy normalized to initial capacity—compared to 2.9% and 22.5% for CC–CV. Additionally, TA achieved a higher average charging power (26.1 kW vs. 24.8 kW) without exceeding 50 °C. Although the algorithm requires more computational effort than CC–CV, its moderate complexity suggests feasibility for real-time integration in battery management systems. These findings highlight TA as a promising adaptive and sustainability-oriented charging strategy. |

Keywords: DC Fast Charging; Battery Thermal Management; State of Health; Thunderstorm Algorithm; CHAdeMO Protocol |

Corresponding Author: Arif Nur Afandi, Department of Electrical and Informatics Engineering, Universitas Negeri Malang, Malang, Indonesia. Email: an.afandi@um.ac.id |

This work is open access under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: S. Samsurizal, A. N. Afandi and M. R. Faiz, “Optimization of DC Fast Charging in CHAdeMO Systems Using Thunderstorm Algorithm with Thermal and Health Constraints,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 129-140, 2026, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v8i1.14505. |

- INTRODUCTION

The rapid growth in the use of electric vehicles (EVs) has driven an increase in the need for efficient, fast, and safe charging systems [1]. One of the charging technologies that is widely adopted is the direct current (DC) charging system with the CHAdeMO protocol [2], which supports high-power charging in a short time. However, conventional charging methods such as constant current (CC) and constant voltage (CV), while simple and widely [3] used, often pose technical challenges, including increased battery temperature and decreased battery health (SoH), which directly affect safety and lifespan [4]. Moreover, these strategies fail to adapt to dynamic thermal and electrochemical conditions, often leading to higher degradation rates [5]. These limitations highlight the need for adaptive optimization approaches that can dynamically adjust charging profiles. One potential candidate is the Thunderstorm Optimization Algorithm (TA), a metaheuristic inspired by the collective behavior of thunderstorm clouds. The research contribution is the development of a TA-based charging model for CHAdeMO systems that simultaneously addresses charging speed, thermal management, and long-term health degradation.

In the fast charging process, the battery temperature can increase significantly due to the high inlet power, which, if not managed properly, will accelerate electrochemical degradation, permanently reduce battery capacity, and shorten battery life [5]. Therefore, a charging strategy is needed that is able to balance charging speed, safe limits of operating temperature, and the preservation of battery conditions [6]. This is where the role of optimization methods becomes very important [7]. Several previous studies have raised this issue from various perspectives. Zentani et al. [8] explained that fast charging without good thermal management can accelerate the decline in battery capacity and pose a safety risk. Ravindran et al. [9] emphasise the importance of integrating active thermal management strategies to maintain battery performance in DC fast charging. In addition, Shaker et al. [10] reviewed charging protocols and found that static approaches, such as constant current and constant voltage, are limited in addressing temperature and internal resistance dynamics.

As technology has evolved, various optimization algorithms based on metaheuristics and natural phenomena have been used in the control of complex and dynamic systems, including battery charging systems [11]-[13]. The research developed a Deep Bayesian Optimization method based on Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) to intelligently formulate a lithium-ion battery charging strategy in a simulated environment [14][15]. This approach considers battery temperature and degradation as constraints, and shows positive results in extending battery life [16]. However, this approach focuses on sequential data-driven learning and does not directly shape the charging current profile in actual fast charging protocols such as CHAdeMO.

Wu et. al designed a Dynamic Programming (DP)-based thermal management strategy that can reduce cooling energy consumption and degradation rate through  battery simulation [17]. Wu's approach emphasizes more on temperature control from the cooling system side, rather than from the adjustment of the charge current profile, and does not evaluate the simultaneous effects on SoH and charging speed [18]. Taking into account the advantages and limitations of previous studies, it can be concluded that there is still a need to develop simulation-based fast charging strategies that can dynamically optimize the charging current profile, taking into account three key aspects simultaneously: charging speed, temperature management, and long-term battery health (SoH). For this reason, this study proposes an optimization model based on the Thunderstorm Algorithm (TA) on DC charging systems with the CHAdeMO protocol, as an alternative solution to conventional methods that are still limited to the fixed current approach.

battery simulation [17]. Wu's approach emphasizes more on temperature control from the cooling system side, rather than from the adjustment of the charge current profile, and does not evaluate the simultaneous effects on SoH and charging speed [18]. Taking into account the advantages and limitations of previous studies, it can be concluded that there is still a need to develop simulation-based fast charging strategies that can dynamically optimize the charging current profile, taking into account three key aspects simultaneously: charging speed, temperature management, and long-term battery health (SoH). For this reason, this study proposes an optimization model based on the Thunderstorm Algorithm (TA) on DC charging systems with the CHAdeMO protocol, as an alternative solution to conventional methods that are still limited to the fixed current approach.

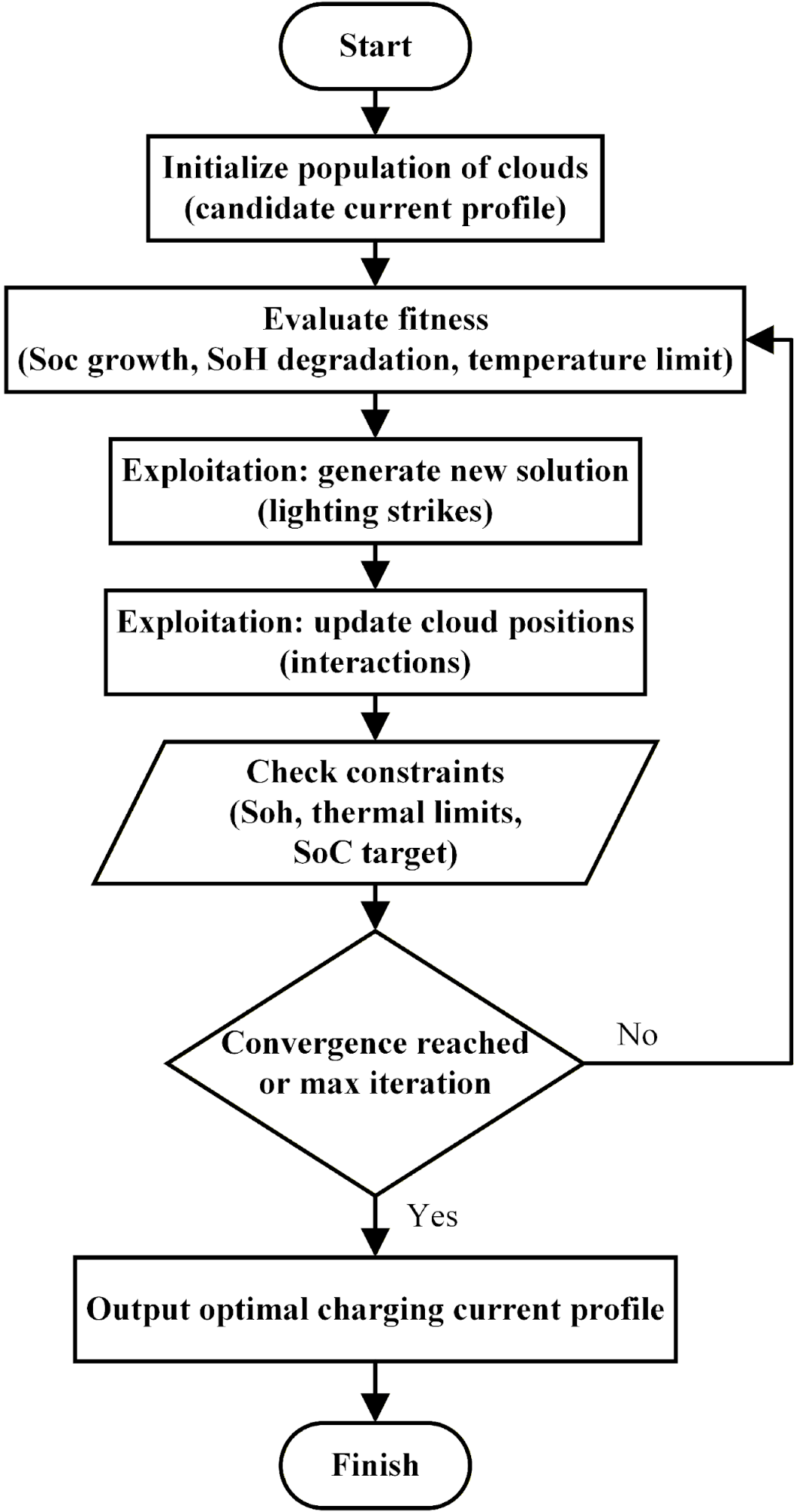

The Thundestorm Algorithm (TA) mimics the collective behavior and movement of thunderstorm clouds in adaptively exploration exploring solution spaces [19]. It has been successfully applied in several electrical power optimization problems [20][21] and is capable of efficiently handling multiple parameters and constraints simultaneously. In this study, the main problem to be addressed is how to optimize the fast charging process in the DC CHAdeMO system so that charging speed can be accelerated without exceeding the battery thermal management while minimizing long-term degradation [22][23]. This reflects the need to design an intelligent and dynamic charging current profile. A formal description of the TA procedure, including pseudocode and a flowchart, is presented in Section 2 to clarify its operational steps and its adaptation to the EV fast-charging context.

Based on the background and formulation of the problem, the purpose of this study is to develop and evaluate a fast charging optimization model based on the Thunderstorm Algorithm (TA) on DC charging systems with the CHAdeMO protocol [24][25]. The model is designed to produce an optimal charging current profile, which considers three key aspects: charging speed, battery temperature management, and long-term battery health (SoH) [26]. The effectiveness of the model is tested through simulations and compared with conventional methods to assess its performance and efficiency improvements [27]-[30]. One of the key indicators used in the evaluation is the State of Charge (SoC), which shows how quickly the battery reaches 100% SoC condition [31]-[33]. A more efficient algorithm should be able to optimize charging in less time, without sacrificing system stability [34][35]. In addition, the State of Health (SoH) is analyzed to measure battery degradation during the charging process [36]. This degradation is affected by factors such as the operating temperature and the charging current applied [37]-[39].

- METHODS

- Conventional Charging Model

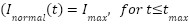

The conventional charging model assumes that the charging current remains constant at its maximum allowable value until the battery reaches either full capacity or the maximum time limit.

|

| (1) |

where  is the maximum allowable current, and

is the maximum allowable current, and  is the time limit of the charging process.

is the time limit of the charging process.

The absorbed power is calculated as:

|

| (2) |

where:  is the charging voltage.

is the charging voltage.

The State of Charge (SoC) and State of Health (SoH) are updated based on cumulative current and degradation factors, while temperature is modeled as:

|

| (3) |

where  is the heating constant (∘C/kW), and

is the heating constant (∘C/kW), and  is the cooling rate of the battery.

is the cooling rate of the battery.

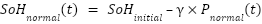

Degradation in the conventional method is expressed as

|

| (4) |

where  is the degradation factor of the battery.

is the degradation factor of the battery.

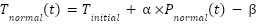

- Thunderstorm Optimization Based Charging Model

The TA optimization method uses an adaptive strategy in determining the charging current profile so that it can maximize the charging speed without exceeding the temperature limit and minimize battery degradation [19]. The TA introduces an adaptive control of charging current to maximize charging speed without violating thermal and health constraints. Unlike the simple random perturbation presented earlier, TA is based on the collective behavior of thunderstorm clouds. Each cloud represents a candidate charging current profile. Lightning strikes simulate exploration by generating new candidate solutions, while cloud movements represent exploitation, gradually converging towards regions of higher solution quality. This mechanism ensures that the current profile adapts to minimize degradation and maintain safe thermal limits, while still achieving rapid SoC growth.

- Current Regulation

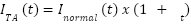

The charging current in  is defined as

is defined as

|

| (5) |

were:

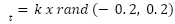

|

| (6) |

with  being a scaling factor and 𝑟𝑎𝑛𝑑 (−0.2, 0.2) a random number controlling variability.

being a scaling factor and 𝑟𝑎𝑛𝑑 (−0.2, 0.2) a random number controlling variability.

Here, the random factor is not purely stochastic but guided by the  ’s collective updating rule, ensuring convergence across the population of candidate solutions.

’s collective updating rule, ensuring convergence across the population of candidate solutions.

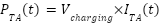

|

| (7) |

with currents that have been modified by the  algorithm

algorithm

- Temperature Regulation

Battery temperature is updated similarly to the conventional model:

|

| (8) |

If  , the current is adaptively reduced:

, the current is adaptively reduced:

|

| (9) |

This step functions as a built-in safety constraint rather than a separate rule, since temperature is explicitly integrated into the optimization fitness function

- Degradation Model

Unlike in the earlier draft, the parameter  is not altered by the algorithm. Instead, TA reduces the effective degradation by dynamically limiting power surges and thermal stress, thereby slowing the cumulative SoH decline.

is not altered by the algorithm. Instead, TA reduces the effective degradation by dynamically limiting power surges and thermal stress, thereby slowing the cumulative SoH decline.

|

| (10) |

- Distinction Between SoH and Battery Life Usage

Two degradation indicators are used in this study:

- State of Health (SoH): the percentage of battery capacity remaining, directly reflecting instantaneous degradation.

- Battery Life Usage: the cumulative percentage of estimated cycle life consumed, calculated as an integral of degradation stress over time.

This distinction ensures that short-term degradation (SoH) and long-term cumulative wear (Battery Life Usage) are both captured. A flowchart is introduced (Figure 1) to clarify the TA procedure:

- Simulation Framework and Parameters

The simulation was conducted to evaluate the performance of the fast charging strategy using conventional approaches and TA based approaches. All simulations are run in a Python-based programmatic environment, with a maximum load duration of 180 minutes and a discrete time resolution of 1 minute per cycle. The simulation does not use direct experimental data, but is based on mathematical modeling that represents the physical dynamics of lithium-ion batteries in the CHAdeMO charging system.

The technical parameters of the system are adjusted to the characteristics of the CHAdeMO protocol, including a battery capacity of 71.4 kWh, a maximum current limit of 125 A, and a charging voltage varying between 50 to 500 V. The charging voltage is calculated linearly based on the State of Charge (SoC), while the battery temperature is dynamically updated using a simple thermal model that takes into account the incoming power and cooling efficiency. The degradation of the State of Health (SoH) and the estimated battery life are calculated as a function of the accumulated power and the duration of the charge.

The two simulation approaches were applied separately for comparison purposes. In the first approach, the conventional method is applied by maintaining the charging current at a constant value (125 A) throughout the duration of the simulation, without considering the operating temperature limit or the state of health of the battery. Instead, the second approach applies an optimization strategy based on the Thunderstorm Algorithm (TA), in which the charging current profile is adjusted adaptively at each time interval. The current adjustment in the TA method takes into account three main constraints simultaneously, namely the maximum temperature of the battery, the SoC achievement target of 100%, and the minimization of SoH degradation during the charging process. The evaluation is carried out based on six main parameters that are continuously monitored during the filling process. The evaluation metrics are summarized in Table 1: charging current, voltage, SoC, SoH, battery life usage, and power. All results are based solely on simulation without experimental validation.

The results presented in this paper are derived entirely from numerical simulations. No experimental or field validation has yet been conducted. As such, the results should be interpreted with caution until verified by physical experiments. The simulation was carried out by applying both scenarios independently. The simulation output data in the form of a time series for each parameter is then analyzed visually. Graphs are used to illustrate the difference in dynamics between the TA method and the conventional method. The evaluation not only includes the achievement of the final SoC, but also considers current stability, power efficiency, and conservation of battery health during the charging process.

Figure 1. Flowchart of TA-Based Charging Model

Table 1. Evaluation Parameters and Description

Parameter | Unit | Description |

Charging Current | A | Actual current values applied at each simulation time |

Charging Voltage | V | Battery voltage calculated based on the linear function of the SoC |

State of Charge (SoC) | % | The percentage of energy stored relative to maximum capacity |

State of Health (SoH) | % | An indicator of battery capacity degradation during the charging process |

Battery Life | % | Cumulative degradation estimates based on accumulated power |

Charging Power | kW | Power delivered to the battery in each minute of simulation |

- RESULT AND DISCUSSION

The simulation was conducted to evaluate the performance of the electric vehicle fast charging system by comparing two approaches: the conventional method and the optimization-based method using the Thunderstorm Optimization Algorithm (TA). The simulation was carried out in a discrete time environment with a resolution of 1 minute, for a maximum duration of 180 minutes, and was run separately for each method. The technical parameters of the charging system follow the specifications of the CHAdeMO protocol and the characteristics of lithium-ion batteries. Table 2 summarizes the main parameters used in the simulation process, including battery capacity, charging current and voltage limits, and operating temperature limits. In addition, parameters for the TA algorithm, such as population size and maximum number of iterations, are also listed as part of the experiment configuration.

Both simulation approaches were applied independently. In the conventional method, the charging current is set at a fixed maximum value (125 A), without considering the effects of temperature or battery degradation. In contrast, the TA-based approach dynamically optimises the charging current by considering three main constraints simultaneously: the maximum temperature limit of the battery (thermal constraint), achieving 100% State of Charge (SoC), and minimising battery health degradation (SoH). The simulation produces output in the form of a time series for six main parameters: charging current, charging voltage, State of Charge (SoC), State of Health (SoH), battery life usage, and actual charging power. In addition to being visually analyzed through graphs, the final results of each method are summarized in Table 3 for quantitative comparison purposes.

Table 2. Simulation Parameters

No | Parameter Name | Symbols / Variables | Value | Unit |

1 | Battery Capacity | battery_capacity | 71,4 | kWh |

2 | Maximum Charging Current | max_current | 125 | A |

3 | Minimum Charging Voltage | charging_voltage_min | 50 | V |

4 | Maximum Charging Voltage | charging_voltage_max | 500 | V |

5 | Initial Voltage | initial_voltage | 400 | V |

6 | Maximum Charging Time | max_charging_time | 180 | minute |

7 | Battery Initial Temperature | – | 30 | °C |

8 | Maximum Operating Temperature of the Battery | max_temperature | 50 | °C |

9 | Minimum Operating Temperature Battery | min_temperature | 30 | °C |

10 | Thermal Constant | thermal_constant | 0,05 | °C per kW |

11 | Cooling Rate | thermal_dissipation_rate | 0,15 | °C per minute |

12 | Initial State of Health | initial_SoH | 1 | (scale 0–1) |

13 | TA Population Size | population_size | 30 | individuals |

14 | TA Maximum Iterations | max_iterations | 500 | Iterations |

15 | Simulation Time per Step | dt | 1 | minute |

16 | SoH degradation per unit of power | 0.00001 × power | 0.00001 × power | per kW |

17 | Battery Life Degradation | 0.000005 × power | 0.000005 × power | % per kW |

Table 3. Simulation Results

Method | Conventional | Thunderstorm Algorithm |

Total Energy Stored (kWh) | 69.5 | 70.8 |

Final SoC (%) | 97.3 | 99.2 |

Final SoH (%) | 97.1 | 98.7 |

Average Temperature (°C) | 47.5 | 44.2 |

Average Power (kW) | 24.8 | 26.1 |

Used Battery Life (%) | 2.25 | 1.84 |

- Charging Current and Voltage Behaviour

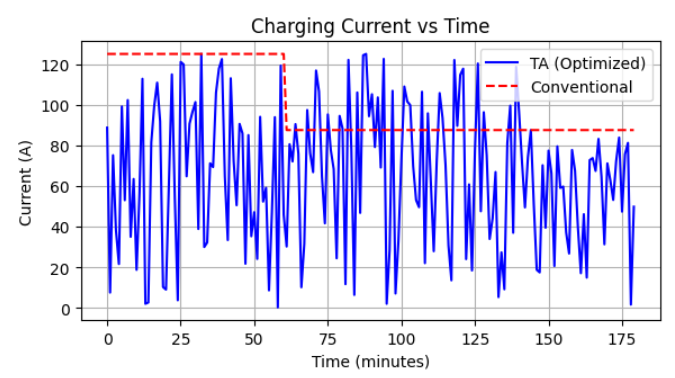

Figure 2 shows the current and voltage profiles of the charge to time for the two compared charging methods: the conventional method and the TA based optimization method. Both show fundamental differences in both the current regulation pattern and the voltage response of the battery during the charging process.

|

|

(a) | (b) |

Figure 2. (a) Current profile and (b) Voltage Profile

In conventional methods, the charging current starts at a fixed value of 125 A, then decreases to about 90 A after a certain point in time—indicating a transition from the constant current (CC) to constant voltage (CV) stage, which is a common approach in fast charging systems. The charging voltage in this method increases sharply and exponentially, as the SoC increases, until it is close to the maximum voltage limit (500 V). This increase in voltage signifies that the system continues to impose high currents even as the battery's internal resistance increases, potentially leading to uncontrollable temperature increases as well as accelerated cell degradation. In contrast, in the TA method, the current profile is dynamic and fluctuates throughout the charging process. This current variation is the result of an iterative optimization process that simultaneously considers operational temperatures, SoC achievement rates, and SoH degradation rates. With a more flexible current setting, the charging voltage in the TA method increases more moderately and linearly. This shows that TA not only avoids excessive current surges, but is also able to maintain the stability of the system by regulating the rate of voltage increase to stay within the safe zone.

These findings reinforce that optimization approaches such as TA can produce a more grid-friendly and battery-friendly charging profile than conventional methods. Intelligent current regulation has a direct impact on voltage, which in turn contributes to the reduction of thermal stress and the long-term efficiency of the battery system. This relationship between current control and voltage response is an important cornerstone in designing a charging strategy between current control and voltage response, this is an important foundation in designing an adaptive charging strategy in modern DC fast charging systems. The ‘conventional method’ in this study follows a CC–CV profile: constant current at 125 A until voltage reaches the upper limit (500 V), followed by constant voltage with a natural tapering current.

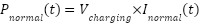

- Battery State Evolution (SoC and SoH)

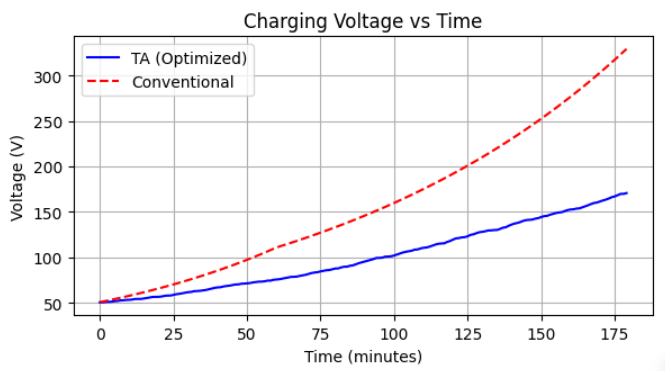

Figure 3 shows the evolution of the State of Charge (SoC) and State of Health (SoH) during the charging process for the two simulation approaches. The graph on the left shows that the conventional method can upgrade the SoC at a much higher speed than the TA method, whereby At the end of 180 minutes, both methods achieved near full charge, with final SoC values of 97.3% for the conventional method and 99.2% for TA. The earlier description of ‘60% vs. 30%’ was incorrect and has been corrected here. This is due to the use of maximum constant current on the conventional approach, which aggressively encourages the rate of energy charge without considering the internal conditions of the battery.

|

|

(a) | (b) |

Figure 3. (a) Evolution State of Charge and (b) Evolution State of Health

However, the high charging speed of conventional methods has negative consequences for battery health, as seen in the SoH graph (right). The decline in SoH in conventional methods is much sharper than that of TA. During the simulation duration, conventional methods experienced SoH degradation of around 2.9%, while TA only experienced a decrease of about 1.3%. This difference suggests that although TA sacrifices some charging speed, this method is significantly more effective in maintaining the chemical stability and internal structure of the battery cell. The TA strategy explicitly regulates the current based on the health level and temperature of the battery. When the system detects an increase in power that has the potential to accelerate degradation, the algorithm will respond by reducing the current, thereby slowing down the decline in SoH. In contrast, conventional approaches lack adaptive mechanisms, so they continue to push the battery under conditions of high thermal and chemical stress.

These findings underscore the importance of optimization-based current control in the fast charging process. In the long-term context, maintaining SoH is essential to extend battery life, reduce replacement costs, and ensure optimal electric vehicle performance. Therefore, the TA approach can be considered not only safer but also more sustainable than conventional strategies. Similar observations were reported by Zhang [14] and Tomaszewska [15], who demonstrated that adaptive current strategies are more effective in reducing degradation rates compared to fixed CC–CV methods.

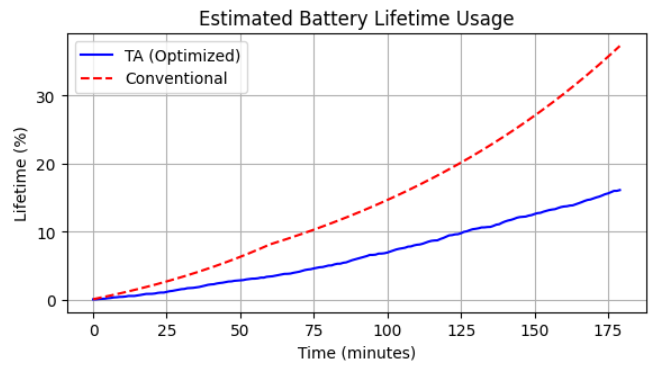

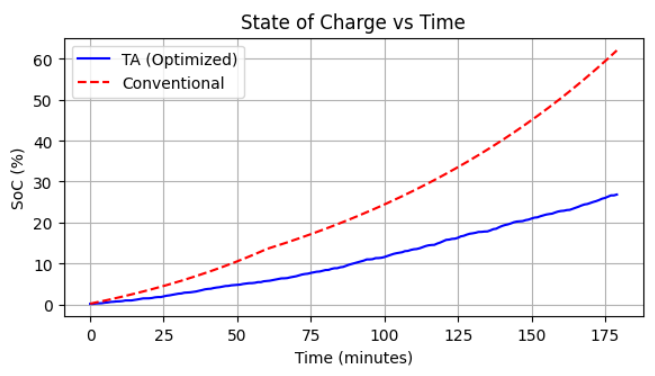

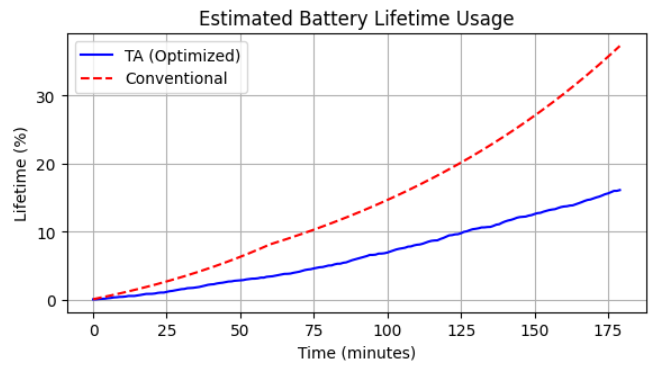

- Estimated Battery Lifetime Usage

Figure 4 shows the estimated battery lifetime usage during the charging process for conventional methods and TA based methods. This parameter is calculated cumulatively based on the energy entering the battery and is used as an indicator of the accumulation of electrothermal stress against the battery cells. The simulation results show that conventional methods cause a much higher rate of battery life degradation than TA. At the end of the charging duration (180 minutes), the conventional method recorded a battery life usage of close to 34%, while the TA method was only about 18%. This difference reflects the significant impact of charging strategies on the long-term durability of batteries.

This condition is consistent with the characteristics of conventional methods that use the maximum current constantly in the early stages of charging, resulting in a large accumulation of incoming power in a short period of time. This accumulation accelerates the chemical aging process of the battery due to increased internal resistance and high operating temperatures. In contrast, the TA method manages the current adaptively based on real-time inputs to temperature and SoH, thus keeping the incoming power level within safe limits and avoiding adverse energy spikes. The slowdown in the degradation rate shown by TA indicates that the adaptive charging strategy not only impacts short-term performance, but also directly affects the battery life cycle. In the context of practical implementation, this approach has the potential to lower the frequency of battery replacement and the overall operational costs of electric vehicles.

Figure 4. Estimated Battery Lifetime

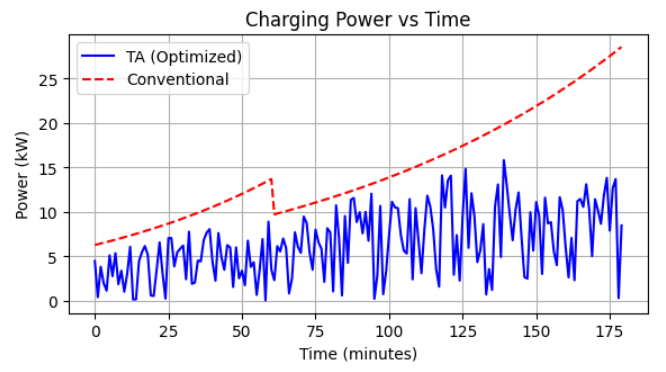

- Charging Power Profile

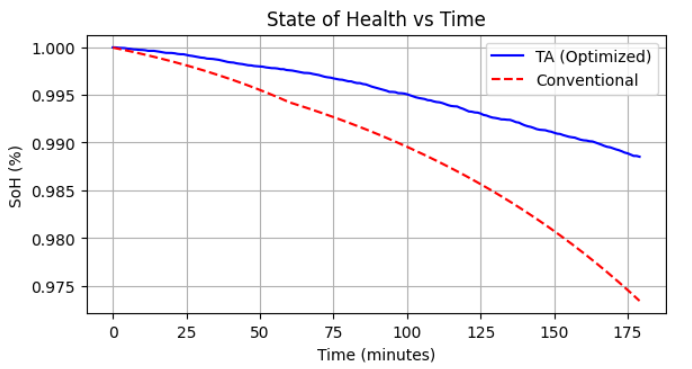

Figure 5 shows the charging power profile over the simulation duration for the two methods compared. Charging power is calculated as the result of times between current and voltage in each time cycle, so it reflects the actual energy load that goes into the battery. This graph illustrates the fundamental difference between conventional charging strategies that are deterministic and TA methods that are adaptive in nature.

Conventional methods show an exponentially increasing power curve, especially in the second half of the charging process. This increase is due to the voltage continuing to increase (close to the maximum limit) while the charging current is still in the high range. This phenomenon creates a surge in incoming power that not only accelerates charging but also increases thermal and electrochemical risks that can accelerate battery cell degradation. In addition, the sudden change at the 60th minute shows a transition from a constant current to a constant voltage strategy that still forces a high power input in the final phase.

In contrast, the power profile in the TA method shows a fluctuating but controlled pattern. These fluctuations come from the iterative results of an optimization process that dynamically adjusts the current based on real-time conditions such as temperature and SoH. Although the average power of the TA is below the conventional method at the beginning of the charge, it tends to be more stable and more evenly distributed throughout the simulation time. This reflects the TA's approach that does not aggressively maximize inbound power, but prioritizes long-term energy stability and efficiency.

Figure 5. Charging Power Profile

- Overall Performance Comparison

Table 3 and visualization of the simulation results show that the Thunderstorm Optimization Algorithm (TA)-based method provides significant advantages in terms of battery durability and long-term energy efficiency. At the end of the simulation duration, the TA method recorded a decrease in SoH by 1.3%, compared to 2.9% in the conventional method. In addition, the accumulated battery life degradation (lifetime usage) only reached 18.4% in TA, much lower than 22.5% in the conventional approach. On the other hand, TA also shows higher performance in terms of energy efficiency. Although TA operates with fluctuating and generally lower currents compared to the conventional method, the voltage profile under TA increased more linearly and stably. As a result, the average power delivered reached 26.1 kW, slightly higher than the 24.8 kW of the CC–CV method. This indicates that voltage dynamics, rather than current magnitude alone, play a dominant role in determining effective charging power, and highlights the advantage of TA in distributing energy more efficiently within safe thermal limits.

Nevertheless, the TA approach is not yet fully optimal in terms of charging speed. The final SoC value achieved at the same time is 99.2% for TA and 97.3% for conventional. Although this difference is relatively small, the time it takes to reach the maximum SoC in TA tends to be longer due to a conservative current adjustment strategy in response to thermal limits and degradation. Significant current fluctuations in TAs can also require more complex and responsive control systems in real implementation. This implies that the implementation of TA in future fast charging systems needs to be balanced with hardware infrastructure and control systems that are adaptive to rapid changes in the flow profile. Taking into account all performance parameters, TA shows potential as a fast charging strategy that not only pays attention to charging time, but also actively maintains battery health and life. This approach can be a strategic solution in the development of electric vehicle charging systems that are oriented towards efficiency and sustainability.

- CONCLUSIONS

This study proposes and evaluates a fast charging optimization model based on the Thunderstorm Algorithm for DC charging systems with the CHAdeMO protocol. The simulation results showed that TA was able to reduce the SoH decrease to 1.3%, as well as reduce battery life usage by 18.4%, compared to 2.9% and 22.5% in conventional methods. In addition, the average charging power increased to 26.1 kW, without exceeding the operating temperature limit. The final SoC achieved with TA (99.2%) was slightly higher than that of the conventional method (97.3%), while simultaneously reducing SoH degradation (1.3% vs. 2.9%) and lifetime usage (18.4% vs. 22.5%). The main limitation of this work is that results are based solely on simulation using simplified thermal and degradation models, without experimental validation. Further research should focus on integrating TA with active cooling, real-time BMS control, and extending the approach to bidirectional Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) scenarios.

DECLARATION

Author Contribution

All authors contributed equally to the main contributor to this paper. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Funding

This project did not obtain any financial assistance from external funding entities or sponsors.

Acknowledgement

This manuscript is part of the doctoral research conducted at the Department of Electrical Engineering and Informatics, Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia. All authors have actively contributed to the completion of this article and approved the inclusion of their names. It is expected that this work will support further research development and be of benefit to readers

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

REFERENCES

- B. V. Vani, D. Kishan, M. W. Ahmad, and B. N. K. Reddy, “An efficient battery swapping and charging mechanism for electric vehicles using bat algorithm,” Comput. Electr. Eng., vol. 118, p. 109357, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2024.109357.

- S. Jaman, B. Verbrugge, O. H. Garcia, M. Abdel-Monem, B. Oliver, T. Geury, and O. Hegazy, “Development and validation of V2G technology for electric vehicle chargers using combo CCS type 2 connector standards,” Energies, vol. 15, no. 19, p. 7364, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/en15197364.

- H. Liu, J. Li, and Z. Chen, “An analytical model for the CC–CV charge of Li-ion batteries with application to degradation analysis,” J. Energy Storage, vol. 29, p. 101342, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2020.101342.

- B. Babu, P. Simon, and A. Balducci, “Fast charging materials for high power applications,” Adv. Energy Mater., vol. 10, no. 22, p. 2001128, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.202001128.

- M. A. H. Rafi and J. Bauman, “A comprehensive review of DC fast-charging stations with energy storage: Architectures, power converters, and analysis,” IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrification, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 345–368, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/TTE.2020.3015743.

- A. Aksoz, B. Asal, E. Biçer, S. Oyucu, M. Gençtürk, and S. Golestan, “Advancing electric vehicle infrastructure: A review and exploration of battery-assisted DC fast charging stations,” Energies, vol. 17, no. 13, p. 3117, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/en17133117.

- M. A. Elkasrawy, S. O. Abdellatif, G. A. Ebrahim, and H. A. Ghali, “Real-time optimization in electric vehicle stations using artificial neural networks”, Electr. Eng., vol. 105, no. 1, pp. 79–89, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00202-022-01647-9.

- A. Zentani, A. Almaktoof, and M. T. Kahn, “A comprehensive review of developments in electric vehicles fast charging technology.” Appl. Sci., vol. 14, no. 11, p. 4728, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/app14114728.

- M. A. Ravindran, R. Rajesh, S. K. Mohan, and S. Kumar, “A novel technological review on fast charging infrastructure for electric vehicles: Challenges, solutions, and future research directions,” Alex. Eng. J., vol. 69, pp. 1–20, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2023.10.009.

- Y. O. Shaker, D. Yousri, A. Osama, A. Al-Gindy, E. Tag-Eldin, and D. Allam, “Optimal charging/discharging decision of energy storage community in grid-connected microgrid using multi-objective hunger game search optimizer,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 120774–120794, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3101839.

- A. N. Afandi, F. C. W. A. and M. Ali, “Aplikasi ORCA algorithm pada optimasi penyediaan daya sistem berbasis mobilitas kendaraan listrik,” Jurnal JEETech, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 103–108, 2023, https://doi.org/10.32492/jeetech.v4i2.4204.

- M. Abd Elaziz, A. Oliva, and S. Mirjalili, “Advanced metaheuristic optimization techniques in applications of deep neural networks: A review,” Neural Comput. Appl., vol. 34, no. 22, pp. 19741–19768, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-021-05960-5.

- S. Samsurizal, A. N. Afandi, and M. R. Faiz, “A comparative analysis of fast charging performance and battery life against charging current variations,” ITEGAM J. Eng. Technol. Ind. Appl., vol. 11, no. 52, pp. 81–86, 2025, https://doi.org/10.5935/jetia.v11i52.1536.

- C. Zhang, J. Jiang, Y. Gao, W. Zhang, Q. Liu, and X. Hu, “Charging optimization in lithium-ion batteries based on temperature rise and charge time,” Appl. Energy, vol. 194, pp. 569–577, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.10.059.

- A. Tomaszewska, Z. Chu, X. Feng, S. O’Kane, and E. Marinescu, “Lithium-ion battery fast charging: A review,” eTransportation, vol. 1, p. 100011, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etran.2019.100011.

- Y. Bouazzi, Z. Yahyaoui, and M. Hajji, “Deep recurrent neural networks based Bayesian optimization for fault diagnosis of uncertain GCPV systems depending on outdoor condition variation,” Alex. Eng. J., vol. 86, pp. 335–345, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2023.11.053.

- Y. Wu, J. Li, S. Li, and Z. Chen, “Optimal battery thermal management for electric vehicles with battery degradation minimization”, Applied Energy, 353, 122090, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.122090.

- R. R. Kumar, C. Bharatiraja, K. Udhayakumar, S. Devakirubakaran, K. S. Sekar, and L. Mihet-Popa, “Advances in batteries, battery modeling, battery management system, battery thermal management, SOC, SOH, and charge/discharge characteristics in EV applications,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 105761–105809, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3318121.

- A. N. Afandi, “Thunderstorm algorithm for assessing thermal power plants of the integrated power system operation with an environmental requirement,” FORTEI JEERI, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 1–9, 2021, https://doi.org/10.46962/forteijeeri.v2i1.18.

- A. N. Afandi, “ORCA algorithm for unit commitment considering electric vehicle inclusion,” FORTEI JEERI, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 1–9, 2021, https://doi.org/10.46962/forteijeeri.v2i1.18.

- L. Gumilar, A. N. Afandi, A. Aripriharta, and M. Sholeh, “Interconnection of battery charging station and renewable energy in electrical power system,” in Proc. Int. Seminar on Application for Technology of Information and Communication (iSemantic), pp. 232–237, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/iSemantic50169.2020.9234209.

- J. G. Qu, Z. Y. Jiang, and J. F. Zhang, “Investigation on lithium-ion battery degradation induced by combined effect of current rate and operating temperature during fast charging,” J. Energy Storage, vol. 52, p. 104811, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2022.104811.

- S. Ou, “Estimate long-term impact on battery degradation by considering electric vehicle real-world end-use factors,” Journal of Power Sources, 573, 233133, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2023.233133.

- X. Zhou et al., “Machine learning assisted multi-objective design optimization for battery thermal management system,” Applied Thermal Engineering, vol. 253, p. 123826, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2024.123826.

- H. Alqahtani and G. Kumar, "Efficient Routing Strategies for Electric and Flying Vehicles: A Comprehensive Hybrid Metaheuristic Review," in IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles, vol. 9, no. 9, pp. 5813-5852, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/TIV.2024.3358872.

- S. Sachan, S. Deb, and S. N. Singh, “Different charging infrastructures along with smart charging strategies for electric vehicles. Sustainable Cities and Society,” Sustainable Cities and Society, vol. 60, p. 102238, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2020.102238.

- L. Jiang, X. Diao, Y. Zhang, J. Zhang, and T. Li, “Review of the charging safety and charging safety protection of electric vehicles,” World Electric Vehicle Journal, vol. 12, no. 4, p. 184, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj12040184.

- I. González Pérez, A. J. Calderón Godoy, and F. J. Folgado, “IoT real time system for monitoring lithium-ion battery long-term operation in microgrids,” Journal of Energy Storage, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2022.104596.

- D. Zhang, L. Li, W. Zhang, M. Cao, H. Qiu, and X. Ji, “Research progress on electrolytes for fast-charging lithium-ion batteries,” Chinese Chemical Letters, vol. 34, no. 1, p. 107122, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2022.01.015.

- H. Çınar, and I. Kandemir, “Active energy management based on meta-heuristic algorithms of fuel cell/battery/supercapacitor energy storage system for aircraft,” Aerospace, vol. 8, no. 3, p. 85, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace8030085.

- C. Jia, W. Qiao, J. Cui, and L. Qu, “Adaptive model-predictive-control-based real-time energy management of fuel cell hybrid electric vehicles,” IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 2681-2694, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/TPEL.2022.3214782.

- S. Saad, F. Ossart, J. Bigeon, E. Sourdille, and H. Gance, “Global Sensitivity Analysis Applied to Train Traffic Rescheduling: A Comparative Study,” Energies, vol. 14, no. 19, p. 6420, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/en14196420.

- S. C. Wang and Y. H. Liu, “A PSO-based fuzzy-controlled searching for the optimal charge pattern of Li-ion batteries,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 62, no. 5, pp. 2983-2993, 2024 https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2014.2363049.

- S. Arora, A. Kapoor, and W. Shen, “A novel thermal management system for improving discharge/charge performance of Li-ion battery packs under abuse,” Journal of Power Sources, vol. 378, pp. 759-775, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2017.12.030.

- N. Nakhodchi, H. Bakhtiari, M. H. Bollen, and S. K. Rönnberg, S. K. “Including uncertainties in harmonic hosting capacity calculation of a fast EV charging station utilizing Bayesian statistics and harmonic correlation,” Electric Power Systems Research, 214, 108933, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsr.2022.108933.

- X. Chen, Y. Hu, S. Li, Y. Wang, D. Li, C. Luo, Y. Yang, “State of health (SoH) estimation and degradation modes analysis of pouch NMC532/graphite Li-ion battery,” Journal of Power Sources, vol. 498, p. 229884, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2021.229884.

- M. J. Eagon, D. K. Kindem, H. Panneer Selvam, and W. F. Northrop, “Neural network-based electric vehicle range prediction for smart charging optimization,” Journal of Dynamic Systems, Measurement, and Control, vol. 144, no. 1, p. 011110. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4053306.

- Y. Wang, A. Liu, Y. Zhu, H. Zhang, Y. Chen and S. -J. Park, “An Adaptive Fast Charging Strategy Considering the Variation of DC Internal Resistance,” in IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 4464-4474, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/TPEL.2022.3230928.

- M. H. Abbasi, Z. Arjmandzadeh, J. Zhang, B. Xu, and V. Krovi, “Deep reinforcement learning based fast charging and thermal management optimization of an electric vehicle battery pack,” Journal of Energy Storage, vol. 95, p. 112466, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2024.112466.

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

| Samsurizal is a Ph.D. candidate at the Department of Electrical Engineering and Informatics, Universitas Negeri Malang, Malang, Indonesia, and a Lecturer at the Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Renewable Energy, Institut Teknologi PLN, Jakarta, Indonesia. His research interests include renewable energy, power systems, artificial intelligence in power engineering, and energy sustainability. Email: samsurizal.2305349@students.um.ac.id |

|

|

| Arif Nur Afandi is a Professor at the Department of Electrical Engineering and Informatics, Universitas Negeri Malang, Malang, Indonesia, and currently serves as Vice Rector IV. He received his B.Eng. from Universitas Brawijaya, Indonesia, M.Eng. from Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia, and Ph.D. from Kumamoto University, Japan. His expertise includes renewable energy, power systems, and optimization methods. Email: an.afandi@um.ac.id |

|

|

|

Mohamad Rodhi Faiz is a Lecturer at the Department of Electrical Engineering and Informatics, Universitas Negeri Malang, Malang, Indonesia. He received his Ph.D. in Mechanical Engineering Science (Energy Conversion) from Universitas Brawijaya, Indonesia, in 2023. His research interests include electrical energy conversion and renewable energy systems. Email: mohamad.rodhi.ft@um.ac.id |

Samsurizal (Optimization of DC Fast Charging in CHAdeMO Systems Using Thunderstorm Algorithm with Thermal and Health Constraints)