ISSN: 2685-9572 Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro

Vol. 7, No. 4, December 2025, pp. 684-701

Bi-LSTM and Attention-based Approach for Lip-To-Speech Synthesis in Low-Resource Languages: A Case Study on Bahasa Indonesia

Eka Rahayu Setyaningsih 1,4, Anik Nur Handayani 2, Wahyu Sakti Gunawan Irianto 3, Yosi Kristian 4

1,2,3 Department of Electrical Engineering and Informatics, Universitas Negeri Malang, Malang, Indonesia

4 Informatics Department, Institut Sains dan Teknologi Terpadu Surabaya, Surabaya, Indonesia

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 23 July 2025 Revised 09 October 2025 Accepted 23 October 2025 |

|

Lip-to-speech synthesis enables the transformation of visual information, particularly lip movements, into intelligible speech. This technology has gained increasing attention due to its potential in assistive communication for individuals with speech impairments, audio restoration in cases of missing or corrupted speech signals, and enhancement of communication quality in noisy or bandwidth-limited environments. However, research on low-resource languages, such as Bahasa Indonesia, remains limited, primarily due to the absence of suitable corpora and the unique phonetic structures of the language. To address this challenge, this study employs the LUMINA dataset, a purpose-built Indonesian audio-visual corpus comprising 14 speakers with diverse syllabic coverage. The main contribution of this work is the design and evaluation of an Attention-Augmented Bi-LSTM Multimodal Autoencoder, implemented as a two-stage parallel pipeline: (1) an audio autoencoder trained to learn compact latent representations from Mel-spectrograms, and (2) a visual encoder based on EfficientNetV2-S integrated with Bi-LSTM and multi-head attention to predict these latent features from silent video sequences. The experimental evaluation yields promising yet constrained results. Objective metrics yielded maximum scores of PESQ 1.465, STOI 0.7445, and ESTOI 0.5099, which are considerably lower than those of state-of-the-art English systems (PESQ > 2.5, STOI > 0.85), indicating that intelligibility remains a challenge. However, subjective evaluation using Mean Opinion Score (MOS) demonstrates consistent improvements: while baseline LSTM models achieve only 1.7–2.5, the Bi-LSTM with 8-head attention attains 3.3–4.0, with the highest ratings observed in female multi-speaker scenarios. These findings confirm that Bi-LSTM with attention improves over conventional baselines and generalizes better in multi-speaker contexts. The study establishes a first baseline for lip-to-speech synthesis in Bahasa Indonesia and underscores the importance of larger datasets and advanced modeling strategies to further enhance intelligibility and robustness in low-resource language settings. |

Keywords: Lip-to-Speech Synthesis; Speech Reconstruction; Sequence Modeling; Low-Resource Language Processing; Indonesian Speech Corpus |

Corresponding Author: Anik Nur Handayani, Department of Electrical Engineering and Informatics, Universitas Negeri Malang, Malang, Indonesia. Email: aniknur.ft@um.ac.id |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: E. R. Setyaningsih, A. N. Handayani, W. S. G. Irianto, and Y. Kristian, “Bi-LSTM and Attention-based Approach for Lip-To-Speech Synthesis in Low-Resource Languages: A Case Study on Bahasa Indonesia,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 684-701, 2025, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v7i4.14310. |

- INTRODUCTION

Humans naturally rely on both auditory and visual cues during speech perception, often monitoring a speaker’s lip movements to supplement the received audio signal. This behavior is evident from infancy, as children aged 4–12 months tend to focus on mouth movements while learning to speak, integrating visual and auditory information simultaneously [1]. Similarly, individuals with hearing impairments can comprehend spoken language by interpreting lip movements and other facial cues [2].

The proven value of visual speech cues has driven extensive research into generating text or speech from visual input [3]. Lip-to-speech synthesis has applications in assistive communication for people with aphonia, speech inpainting to restore missing audio segments [4], and improving speech clarity in noisy communication environments, as demonstrated in recent work on WaveNet-based speech denoising [5] and more recent advances in speech inpainting [6][7]. Over time, the field has advanced significantly, particularly for high-resource languages such as English, Mandarin, and Japanese. Recent approaches have introduced encoder-decoder architectures like Lip2Wav [8] and vocoder-based models [9], as well as diffusion-based [10] (e.g., GlowLTS [11], Diffusion LTS [12]) and transformer-based approaches [13] [14], as well as newer frameworks like RobustL2S [15] and NaturalL2S [16], which produces natural-sounding, temporally aligned speech from silent video. Other recent architectures, such as SVTS [17], Lip2AudSpec [18], and LipVoicer [19], and Intelligible L2S [20] further demonstrate scalable, attention-guided, or lip-reading–conditioned speech generation from video. These models often incorporate attention mechanisms to focus on the most informative temporal segments of lip motion. Likewise, LSTM-based autoencoders, including Bi-LSTM and DBLSTM variants, have shown strong performance in capturing bidirectional temporal dependencies for audio–visual mapping tasks [21]-[23].

Despite these advances, research on lip-to-speech synthesis in low-resource languages such as Bahasa Indonesia remains scarce. Widely used corpora in English, such as GRID [24], LRS2 and LRS3 contain tens of thousands of sentences and hundreds of hours of recordings, enabling rapid model development. Additional corpora such as TCD-TIMIT [25] and AVSpeech [26][27], and LUMINA Data in Brief [28] further expand resources in English and provide new Indonesian benchmarks. In contrast, comparable resources in Bahasa Indonesia are nearly absent. Table 1 illustrates the stark disparity in dataset availability across languages.

Table 1. Comparison of widely used audio-visual datasets and the Indonesian LUMINA dataset.

Dataset | Language | Speakers | Utterances / Duration | Characteristics |

GRID [24] | English | 34 | 34,000 sentences | Fixed grammar, controlled recordings. |

LRS2 [29] | English | ~1,000 (TV) | 100,000+ sentences | Natural data from BBC, high variability. |

LRS3 [30] | English | Multi-speaker | 400+ hours | TED Talks, large-scale, diverse accents. |

Lip2Wav [8] | English | 5 | ~120 hours | Designed specifically for lip-to-speech. |

AVSpeech [26] | Multi-lang | 150k+ speakers | 3,000+ hours | Large-scale, cross-lingual dataset. |

LUMINA [31] | Indonesian | 14 | ~14,000 sentences (~12h) | Broad syllabic coverage, but limited in scale. |

As shown, English corpora such as LRS2 [29][32] and LRS3 [30] provide over 100,000 sentences and hundreds of hours of data, whereas LUMINA offers only 14 speakers and ~14,000 sentences (equivalent to around 12 hours). Although LUMINA is the first dataset designed specifically for Indonesian lip-to-speech synthesis with diverse syllabic coverage, its limited scale poses challenges for generalization, speaker inclusivity, and model robustness. In addition, the linguistic properties of Bahasa Indonesia, dominated by open syllables (CV), relatively flat prosody, and high homophony, introduce unique difficulties in mapping visual to acoustic information [33][34].

Although recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of modern architectures such as Transformers [13], Vision Transformers with autoencoders [14], and diffusion-based models, their application requires extremely large-scale datasets and high computational resources. Such requirements are challenging to meet in the Indonesian context, where data availability remains limited to small-scale corpora, such as LUMINA, and computational constraints restrict the feasibility of training deep models. In contrast, Bi-LSTM offers a balanced trade-off: it is computationally more efficient, capable of capturing bidirectional temporal dependencies critical in modeling coarticulation effects of lip movements, and has been empirically proven to generalize well even under low-resource conditions [21]. For these reasons, this study adopts Bi-LSTM as the backbone of the multimodal autoencoder, while enhancing its performance through the integration of multi-head attention to better capture informative temporal features.

Therefore, this study aims to establish a baseline system for lip-to-speech synthesis in Bahasa Indonesia by proposing and evaluating an Attention-Augmented Bi-LSTM Multimodal Autoencoder, implemented as a two-stage pipeline consisting of (1) an audio autoencoder to learn compact latent speech representations, and (2) a visual encoder using EfficientNetV2-S with Bi-LSTM and multi-head attention to predict these latent features from silent video. The main contribution is not only the methodological design tailored for a low-resource language but also providing the first quantitative benchmarks, achieving maximum scores of PESQ 1.465, STOI 0.7445, ESTOI 0.5099, and MOS improvements up to 4.0 in multi-speaker female scenarios. To provide a clearer understanding of how this system is designed and implemented, the following section describes the methodological framework in detail, including dataset preprocessing, model architecture, and evaluation procedures.

- THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

This section presents the fundamental theories related to autoencoders, Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM), and attention mechanisms that underlie the development of the proposed model. Additionally, it outlines the conceptual integration of Bi-LSTM and attention within a multimodal autoencoder, implemented as a two-stage pipeline, which serves as the theoretical foundation of this research.

- Autoencoder

An autoencoder is an artificial neural network architecture designed for representation learning [35] by compressing input data into a lower-dimensional latent representation (encoding) and then reconstructing it back to its original form (decoding). In the broader scope of machine learning, autoencoders are widely used for tasks such as dimensionality reduction, anomaly detection, denoising, and feature extraction, since they can learn directly from raw data without requiring labeled information. In the context of lip-to-speech synthesis, an autoencoder maps a sequence of lip movement images into an information-rich latent space, which is then converted into acoustic features such as Mel-spectrograms. This process enables the separation and independent processing of visual understanding and speech production, aligning with machine learning objectives to capture essential patterns and discard noise. By combining autoencoders with other architectures such as CNNs, LSTMs, and attention mechanisms, the model can learn complex multimodal relationships and be integrated with generative components [36] like neural vocoders [9] to produce intelligible and natural-sounding speech.

- Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM)

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) is a variant of the Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) designed to address the vanishing gradient problem in sequential data through the use of gating mechanisms. LSTM maintains important information via the cell state and regulates information flow through input, forget, and output gates [37]-[39]. Bi-LSTM is an extension of LSTM that processes sequences in both forward and backward directions, enabling each prediction to consider both past and future context [22],[40]. In lip-to-speech synthesis, this bidirectional processing helps capture subtle transitions between visemes, which depend on both preceding and subsequent phonemes [41].

- Attention Mechanism

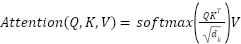

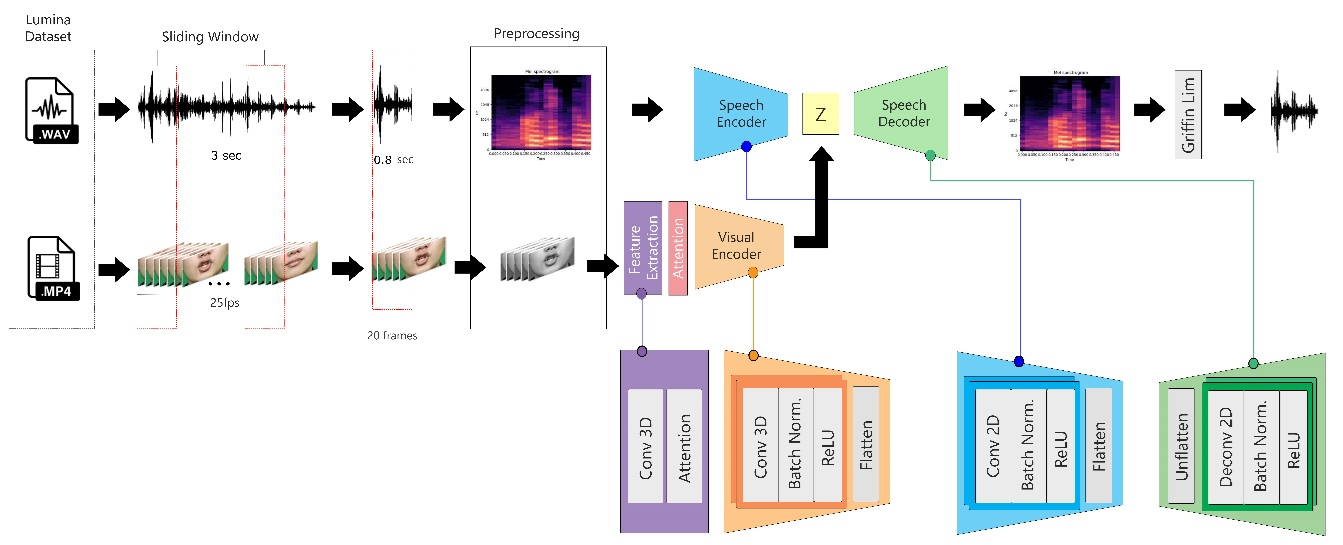

An Attention mechanism is included in this model, located specifically within the visual model. Its function is to direct the model's attention to variations in the speaker's lip movements. The method involves weighting the features extracted from a frame based on their relevance to frames preceding and succeeding it. Unlike the typical use of Attention in text processing [42]-[44] where fully connected layers usually create 1-dimensional  ,

,  , and

, and  vectors, video processing here employs 2DConv layers to produce 2-dimensional vectors containing spatial information. In the context of attention, the term “head” refers to an independent mechanism where each instance performs its attention computation, as shown in Equation (1). The Lip-to-Speech model developed in this study incorporates multi-head attention to acquire significant and relevant features from lip movements. By employing this mechanism, the model can distribute its focus across multiple heads, with each head operating in parallel on different subsets of information.

vectors, video processing here employs 2DConv layers to produce 2-dimensional vectors containing spatial information. In the context of attention, the term “head” refers to an independent mechanism where each instance performs its attention computation, as shown in Equation (1). The Lip-to-Speech model developed in this study incorporates multi-head attention to acquire significant and relevant features from lip movements. By employing this mechanism, the model can distribute its focus across multiple heads, with each head operating in parallel on different subsets of information.

|

| (1) |

The outputs of all heads are combined to form a final representation, as shown in Equation (2). This approach produces richer and more comprehensive representations. Consequently, the lip-to-speech model can capture more complex and distinctive features of lip movements, thereby providing the essential information required for generating accurate speech predictions [11].

|

| (2) |

- Integration of Bi-LSTM and Attention in a Multimodal Autoencoder

The combination of Bi-LSTM and attention mechanisms [45] within a multimodal autoencoder framework, implemented as a two-stage pipeline, provides two primary advantages:

- Bidirectional Context Modelling

Bi-LSTM captures both forward and backward temporal dependencies in visual lip movement data, which is critical for predicting ambiguous phonemes.

- Dynamic Focus

Attention enables the model to emphasize relevant visual frames for specific phonemes, reducing confusion caused by co-articulation or similar visemes.

This conceptual framework has been proven effective in speech recognition [23], machine translation [46], and visual speech recognition [10],[47]. Importantly, the combination of Bi-LSTM and multi-head attention in a two-stage multimodal pipeline allows richer temporal modeling and dynamic feature selection, which has been shown in prior studies to improve robustness in low-resource scenarios. However, its application for Bahasa Indonesia with a speaker-specific strategy in lip-to-speech synthesis remains underexplored, making it the focus of this research.

- METHODOLOGY

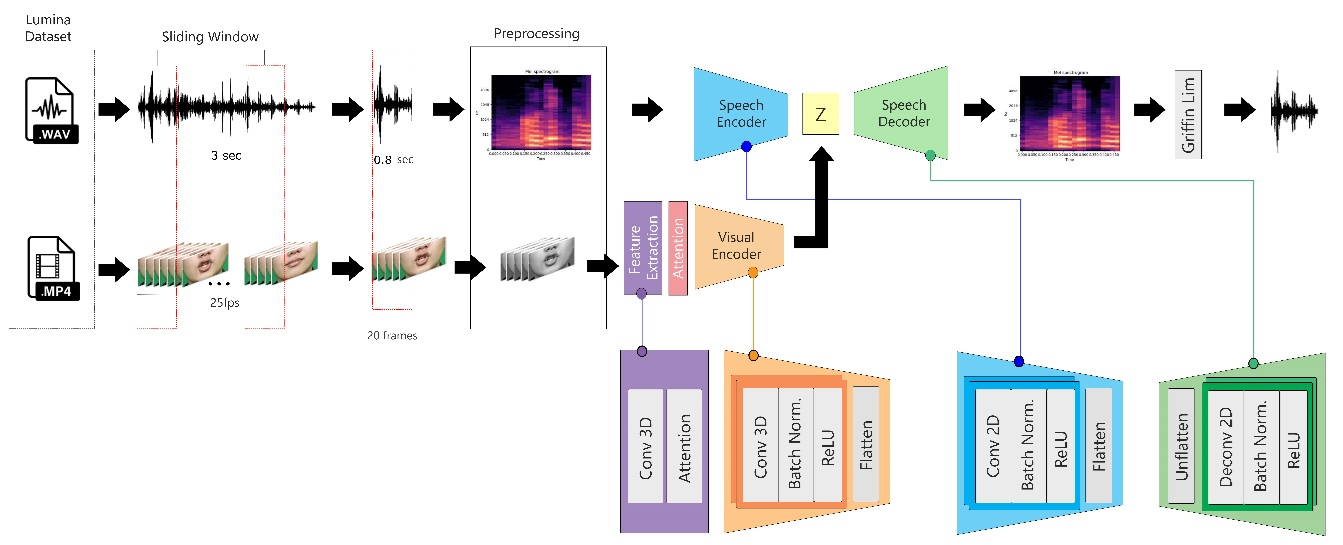

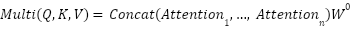

The methodology of this study is based on an Attention-Augmented Bi-LSTM Multimodal Autoencoder, implemented as a two-stage pipeline that integrates both audio and visual information to synthesize speech from lip movements. The overall architecture, illustrated in Figure 1, consists of two interconnected components: (1) an audio autoencoder that learns compact latent representations of speech signals, and (2) a visual encoder that predicts these latent features from silent lip movements. The input data consists of synchronized audio and video extracted from the LUMINA dataset. Audio signals are segmented using a sliding window, preprocessed into Mel-spectrograms, and then passed through the speech encoder–decoder pipeline. In parallel, video sequences are preprocessed into grayscale frames and fed into a feature extractor, followed by the visual encoder with attention and Bi-LSTM modules. The visual encoder predicts the latent representation generated by the audio autoencoder, thereby creating a direct mapping between lip movements and speech features.

Figure 1. Two-Stage Audio–Visual Latent Prediction Pipeline

- Dataset

This study employed the Linguistic Unified Multimodal Indonesian Natural Audio-Visual (LUMINA) dataset (Figure 2) [31][28], a custom-built multimodal corpus specifically designed for Indonesian lip-to-speech research. Unlike existing corpora such as GRID [24], which are primarily in English, LUMINA provides synchronized audio and video recordings in Bahasa Indonesia, enabling experiments that address language-specific phonetic and visual articulation characteristics. The dataset contains recordings of 14 speakers, including 9 males and 5 females. Each speaker contributed a series of utterances covering a diverse range of Indonesian syllables, vowels, and consonant variations, ensuring sufficient phonetic coverage. Video recordings were captured at 25 fps with a resolution of 1280×720 pixels, while audio was sampled at 16 kHz in WAV format. Each video was first resized to 250×150 pixels, with the cropping focused on the central lip region, and then converted into grayscale frames to reduce computational complexity while preserving essential visual cues.

The input video data in this study was processed in the form of sequential 20-frame segments, ensuring that each training instance captured a continuous portion of lip movements. The choice of a 20-frame sequence was motivated by both phonetic and computational considerations. Phonetic studies show that the average duration of a syllable in Bahasa Indonesia is 0.2–0.25 seconds. Analysis of the dataset indicates that most words consist of two syllables, followed by three-syllable words as the second most frequent. Thus, approximately 0.7–0.8 seconds are required to pronounce three syllables, which represents a natural linguistic unit. Since the video was recorded at 25 fps, this duration corresponds to 20 consecutive frames. This design is consistent with earlier studies, such as Ephrat [48] which demonstrated that relatively short frame windows (9–15 frames) can achieve strong performance. Although more recent lip-to-speech research [49][50] employs longer frame windows (1–3 seconds) to capture broader temporal context, such approaches demand significantly higher computational resources. Therefore, the use of 20 frames per sequence provides an optimal balance between temporal coverage and computational efficiency.

Figure 2. Example of the LUMINA dataset

In the experimental phase, objective evaluations were performed using PESQ, STOI, and ESTOI metrics across all 14 speakers, as presented in Table 2. Based on these evaluations, the dataset was reorganized into six subsets to facilitate a more systematic analysis of both speaker-dependent and speaker-independent performance. As illustrated in Table 3, the subsets consist of two female speakers representing individual female-specific cases, two male speakers representing individual male-specific cases, and two multi-speaker groups comprising five female speakers and five male speakers, respectively. This partitioning provides a balanced framework for comparing single-speaker and gender-based multi-speaker scenarios. The primary motivation for selecting LUMINA lies in its speaker-specific structure and language focus. Previous studies have demonstrated that restricting models to fewer or single speakers often yields higher accuracy due to reduced inter-speaker variability [51]. Moreover, since research on lip-to-speech synthesis in Bahasa Indonesia remains scarce, LUMINA offers a crucial foundation for advancing this domain.

Table 2. Evaluation Results of PESQ, STOI, and ESTOI for Individual Speakers

No. | Speaker | Number of Data | PESQ | STOI | ESTOI | Mean (PESQ, STOI, ESTOI) |

1 | FEMALE | P08 | 1082 | 1.0959 | 0.1697 | 0.0327 | 0.4328 |

2 | P03 | 1022 | 1.0905 | 0.1653 | 0.0405 | 0.4321 |

3 | P10 | 1017 | 1.0904 | 0.1482 | 0.0331 | 0.4239 |

4 | P14 | 1090 | 1.0871 | 0.1445 | 0.0324 | 0.4213 |

5 | P11 | 1018 | 1.0709 | 0.1410 | 0.0271 | 0.4130 |

6 | MALE | P06 | 1113 | 1.1148 | 0.2012 | 0.0797 | 0.4652 |

7 | P04 | 1093 | 1.1106 | 0.1979 | 0.0631 | 0.4572 |

8 | P01 | 1073 | 1.1083 | 0.1856 | 0.0711 | 0.4550 |

9 | P13 | 1025 | 1.0950 | 0.1971 | 0.0707 | 0.4543 |

10 | P07 | 1051 | 1.0990 | 0.1744 | 0.0452 | 0.4395 |

11 | P12 | 1055 | 1.0809 | 0.1575 | 0.0505 | 0.4296 |

12 | P09 | 1062 | 1.1006 | 0.1384 | 0.0160 | 0.4183 |

13 | P05 | 1108 | 1.1061 | 0.0909 | 0.0255 | 0.4075 |

Table 3. Dataset Subset Partitioning

Subset | Speaker | Number of Data |

1 | P06 (m) | 1113 |

2 | P04 (m) | 1093 |

3 | P08 (f) | 1082 |

4 | P03 (f) | 1022 |

5 | Male | 5344 |

6 | Female | 5529 |

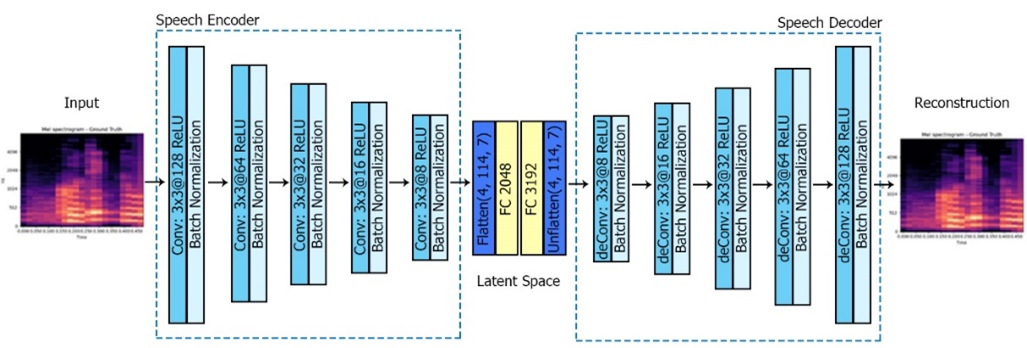

- Audio Model

The audio component of the two-stage pipeline is designed as an autoencoder to learn a compact latent representation of speech from its Mel-spectrogram [52], as shown in Figure 3. In the audio encoder stage, the input Mel-spectrogram is processed through a sequence of 2D convolutional layers (Conv2D) with a kernel size of 3×3, each followed by Batch Normalization to stabilize and accelerate training, and ReLU activation to introduce non-linearity. This sequence of convolutional blocks is repeated iteratively, progressively reducing the spatial dimensions while increasing the depth of feature maps to capture high-level acoustic features.

Figure 3. Architecture of the Audio Model

After convolutional processing, the feature maps are flattened into a 1D vector, optionally passed through a fully connected layer (MLP) to form the latent space variable. This latent space represents the most informative and compressed features of the input speech. The latent dimension was set to 2048 as a compromise between representation richness and computational efficiency: smaller dimensions may discard important phonetic details, while larger ones could cause overfitting and increase training cost. The value of 2048 is consistent with prior autoencoder-based speech modelling studies, and ensures sufficient capacity to preserve acoustic diversity while remaining feasible for integration with the visual encoder. Table 4 summarizes the encoder–decoder structure. The decoder mirrors the encoder but introduces ConvTranspose2D layers to restore the original Mel-spectrogram dimensions. The process starts with a fully connected layer sized to match the flattened output of the encoder, followed by an unflattening operation to recover the 2D feature map structure. Subsequent transposed convolutional blocks progressively reconstruct the spectral resolution. The final Conv2D layer, without activation or normalization, produces the output Mel-spectrogram with maximum clarity and minimal distortion. The key difference between the encoder and decoder is the use of transpose convolution layers in the decoder to upsample the feature maps, restoring the spectral resolution required for accurate speech reconstruction. The design ensures that the reconstructed Mel-spectrogram closely matches the original, minimizing mean squared error (MSE) loss during training.

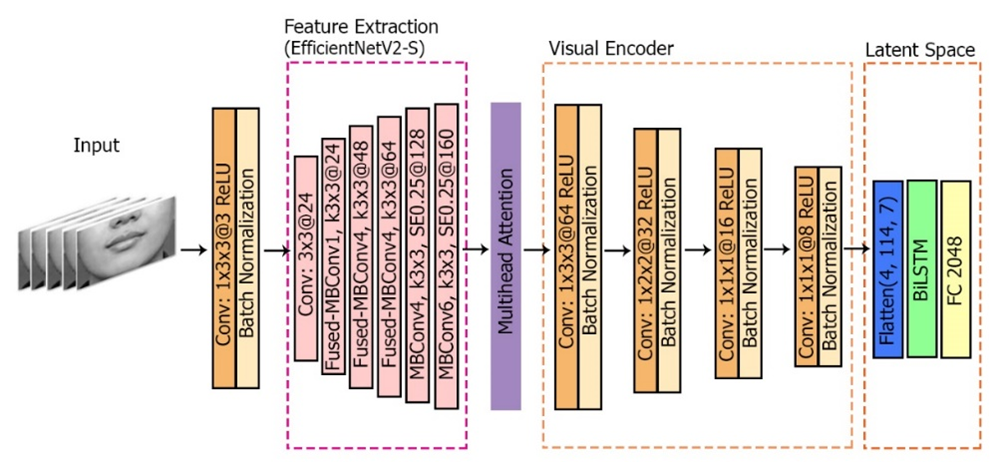

- Visual Model

The visual component of the two-stage pipeline is designed to map sequences of lip movements into latent speech representations. Each input sequence consists of 20 consecutive video frames, cropped to a resolution of 250×150 pixels cantered on the lip region [53] and subsequently converted into grayscale format. This preprocessing step ensures that the model focuses on the articulatory region while reducing computational complexity. The preprocessed frames are first passed through a 3D convolutional layer (Conv3D), followed by Batch Normalization and ReLU activation, to adapt the grayscale input into a feature space compatible with the subsequent backbone network. The sequence is then fed into the EfficientNetV2-S backbone, which serves as the principal feature extractor. EfficientNetV2-S was selected for its relatively lightweight architecture, reduced parameter count, and fast inference time, while maintaining competitive representational quality [54].

The extracted features are subsequently refined by a multi-head attention mechanism (Figure 4), which distributes attention across multiple independent heads. This allows the model to emphasize subtle inter-frame variations and assign higher weights to visually salient movements, thereby mitigating ambiguity caused by coarticulation and visually similar visemes. Following the attention module, the features undergo further compression through a sequence of Conv3D layers, ensuring that spatiotemporal information is retained while dimensionality is reduced. The resulting feature maps are then flattened and projected into a 2048-dimensional latent space via a fully connected layer. This dimensionality was selected as a balance between representation richness and computational efficiency, and to ensure compatibility with the latent space of the audio autoencoder.

Figure 4. Architecture of the Visual Model

Finally, the encoded features are passed to a Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM) layer. By processing the sequence in both forward and backward directions, Bi-LSTM captures long-range temporal dependencies and incorporates contextual information from preceding and succeeding frames. This capability is essential for modelling natural coarticulation effects and ensures that visual input is accurately mapped to corresponding speech features. It is important to note that this study implements four different model variants:

- Model 1 – LSTM: Utilizes a single LSTM without attention.

- Model 2 – Bi-LSTM: Employs a Bi-LSTM without attention.

- Model 3 – Bi-LSTM + 4-head attention: Integrates a multi-head attention module with four heads before the sequence modelling stage.

- Model 4 – Bi-LSTM + 8-head attention: Incorporates eight attention heads combined with Bi-LSTM, representing the most complete configuration

Table 5 corresponds to the full architecture of Model 4, which integrates the feature extractor, the multi-head attention mechanism, and the Bi-LSTM module. For the other three models, the hyperparameter configurations and base layers remain identical to those in Table 5. The only differences are the removal of attention (Models 1 and 2) or the substitution of LSTM/Bi-LSTM in the sequence modelling stage. This systematic design guarantees fair comparability across all experiments. All four models are trained under identical hyperparameter settings, ensuring that performance variations can be attributed solely to architectural differences rather than external factors. The core backbone of the architecture remains consistent, while specific components are selectively enabled or disabled depending on the model specification. In this way, any observed differences in performance can be directly linked to the inclusion of the attention module or the choice between LSTM and Bi-LSTM sequence modeling.

- Evaluation

The performance of the proposed two-stage pipeline was evaluated using a combination of objective metrics, subjective listening tests, and statistical significance analysis. Before evaluation, all models were trained using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001 [54] and Mean Squared Error (MSE) as the loss function, a configuration chosen to balance convergence speed and stability while minimizing reconstruction error. After training, model outputs were systematically assessed through three objective measures, PESQ, STOI, and ESTOI, to capture speech quality and intelligibility, complemented by a Mean Opinion Score (MOS) test involving 40 participants to reflect perceptual judgments. Finally, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied to determine whether the differences among model variants were statistically significant, ensuring that both numerical and perceptual improvements were supported by robust statistical validation.

- Objective Evaluation

Three established objective metrics were employed to evaluate the quality and intelligibility of the generated speech:

- Perceptual Evaluation of Speech Quality (PESQ) [55] A standardized measure that predicts perceptual quality by comparing generated speech with reference ground truth signals. The PESQ score typically ranges from –0.5 to 4.5. Higher scores indicate better quality and closer resemblance to the reference, whereas values below 1.0 represent very poor perceptual quality.

- Short-Time Objective Intelligibility (STOI) [56][57] An intelligibility metric that estimates how well a listener can understand speech under noisy or degraded conditions. STOI scores range from 0 to 1. A value close to 1 indicates highly intelligible speech, while values near 0 indicate unintelligibility. In general, a STOI value of 0.75 is considered the threshold for acceptably intelligible speech.

- Extended Short-Time Objective Intelligibility (ESTOI) [58] An extension of STOI designed to capture longer temporal modulations that are important for speech comprehension. Like STOI, scores range from 0 to 1, with 0.75 commonly regarded as a threshold for acceptable intelligibility. ESTOI tends to be more sensitive to spectral distortions and temporal fluctuations, and it may yield lower values than STOI in conditions where background noise or spectral degradation significantly affect the signal.

These objective measures provide complementary insights: PESQ reflects perceptual similarity, while STOI and ESTOI capture intelligibility under different temporal sensitivities. Together, they provide a quantitative benchmark for evaluating reconstruction fidelity across various model variants.

- Subjective Evaluation (MOS Test)

In addition to objective metrics, a Mean Opinion Score (MOS) test was conducted to evaluate perceptual quality from a human listener's perspective. A total of 40 respondents participated in the test. Each respondent was asked to rate the generated speech samples on a five-point scale (0–5), where 5 indicated speech that was perceived as the clearest and most intelligible, and 0 indicated completely unintelligible output. Each participant was presented with audio samples generated from all model variants (LSTM, Bi-LSTM, Bi-LSTM with 4-head attention, and Bi-LSTM with 8-head attention) across all dataset subsets (individual speakers and multi-speaker groups). The MOS for each condition was obtained by averaging the ratings across all participants, providing a reliable measure of naturalness and intelligibility to complement the objective evaluation metrics.

Table 4. Audio Model

Layer | Type | Kernel | Input | Output |

Encoder |

1 | 2D CNN | (3,3) | 1 | 128 |

2 | Batch Normalization 2D |

3 | ReLU |

4 | 2D CNN | (3,3) | 128 | 64 |

5 | Batch Normalization 2D |

6 | ReLU |

7 | 2D CNN | (3,3) | 64 | 64 |

8 | Batch Normalization 2D |

9 | ReLU |

10 | 2D CNN | (3,3) | 64 | 32 |

11 | Batch Normalization 2D |

12 | ReLU |

13 | 2D CNN | (3,3) | 32 | 16 |

14 | Batch Normalization 2D |

15 | ReLU |

16 | 2D CNN | (3,3) | 16 | 8 |

17 | Batch Normalization 2D |

18 | ReLU |

Latent Space |

19 | Flatten | - | (4, 114, 7) | 3192 |

20 | Linear | - | 3192 | 2048 |

21 | Linear | - | 2048 | 3192 |

22 | Unflatten | - | 3192 | (4, 114, 7) |

Decoder |

23 | 2D CNN Transpose | (3,3) | 8 | 4 |

24 | Batch Normalization 2D |

25 | ReLU |

26 | 2D CNN Transpose | (3,3) | 4 | 8 |

27 | Batch Normalization 2D |

28 | ReLU |

29 | 2D CNN Transpose | (3,3) | 4 | 8 |

30 | Batch Normalization 2D |

31 | ReLU |

32 | 2D CNN Transpose | (3,3) | 8 | 16 |

33 | Batch Normalization 2D |

34 | ReLU |

35 | 2D CNN Transpose | (3,3) | 16 | 32 |

36 | Batch Normalization 2D |

37 | ReLU |

38 | 2D CNN Transpose | (3,3) | 64 | 64 |

39 | Batch Normalization 2D |

40 | ReLU |

41 | 2D CNN Transpose | (3,3) | 64 | 128 |

42 | Batch Normalization 2D |

43 | ReLU |

44 | 2D CNN Transpose | (3,3) | 128 | 1 |

Table 5. Visual Model

Layer | Type | Kernel | Input | Output |

Feature Extrator |

1 | Conv3D | (1,3,3) | 1 | 3 |

2 | Batch Normalization 3D |

3 | ReLU |

4 | Conv 3x3 | - | 3 | 24 |

5 | Fused-MBConv1, k3x3 | - | - | 24 |

6 | Fused-MBConv4, k3x3 | - | - | 48 |

7 | Fused-MBConv4, k3x3 | - | - | 64 |

8 | MBConv4, k3x3, SE0.25 | - | - | 128 |

9 | MBConv6, k3x3, SE0.25 | - | - | 160 |

Attention |

10 | Multihead Attention | 8 | 160 | 512 |

Encoder |

11 | Conv3D | (1,3,3) | 512 | 256 |

12 | Batch Normalization 3D |

13 | ReLU |

14 | Conv3D | (1,2,2) | 256 | 128 |

15 | Batch Normalization 3D |

16 | ReLU |

17 | Conv3D | (1,1,1) | 128 | 64 |

18 | Batch Normalization 3D |

19 | ReLU |

20 | Conv3D | (1,1,1) | 64 | 32 |

21 | Batch Normalization 3D |

22 | ReLU |

23 | Conv3D | (1,1,1) | 32 | 16 |

24 | Batch Normalization 3D |

25 | ReLU |

26 | Conv3D | (1,1,1) | 16 | 8 |

27 | Batch Normalization 3D |

28 | ReLU |

29 | Flatten |

30 | BiLSTM | - | 4000 | 2048 |

31 | Linear | - | 2048 | 2048 |

- RESULT AND DISCUSSION

The proposed pipeline was evaluated using a combination of objective metrics (PESQ, STOI, ESTOI) and a subjective Mean Opinion Score (MOS) test. These complementary measures provide both quantitative and perceptual insights into the quality and intelligibility of the generated speech, forming the basis for the analysis presented in the following subsections.

- Audio Model

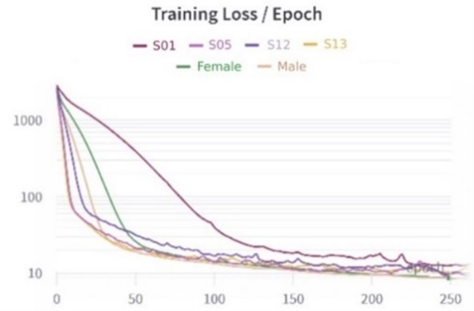

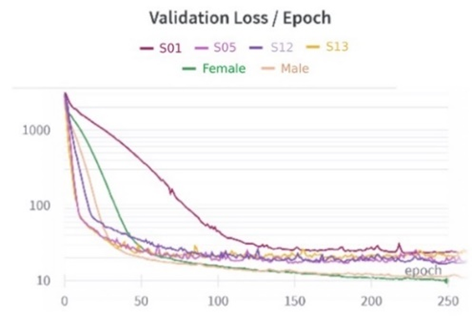

Before integrating the visual modality, an audio autoencoder was first developed as a baseline model to establish a compact latent space for speech. The purpose of this stage is not to produce high-quality reconstructed audio, but rather to ensure that the latent representation captures sufficient spectral and temporal information. This latent space then serves as the target domain for mapping from visual input in the subsequent multimodal pipeline. Designed to represent audio in a one-dimensional latent space of length 2048, the Audio Autoencoder was developed primarily as a feature learning mechanism, rather than as a final speech synthesis system. Its main objective is to capture compact yet informative latent representations of speech that can later be aligned with visual features in the multimodal pipeline. Six instances of the model were trained, each corresponding to the dataset subsets described earlier. As shown in Figure 5, both Training and Validation Loss values consistently decreased over 250 epochs, demonstrating the model’s ability to learn a meaningful latent representation. The Training Loss converged smoothly to a value around 10, while the Validation Loss displayed higher fluctuations and remained generally above the Training Loss. These fluctuations are expected, as the autoencoder focuses on compressing and reconstructing latent speech features, which may not always generalize perfectly to unseen data.

|

|

(a) | (b) |

Figure 5. Visualisation of Audio Autoencoder Model (a) Training Loss (b) Validation Loss

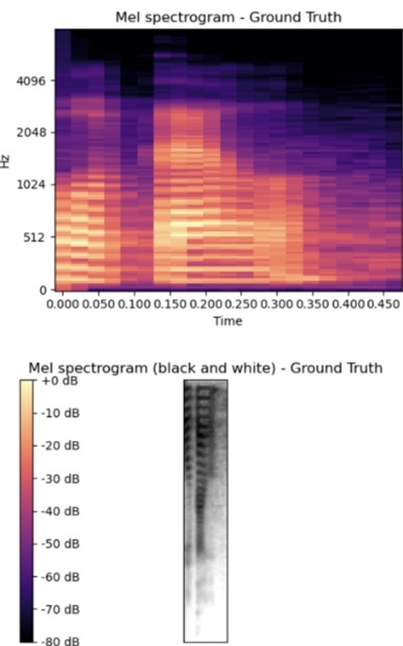

Table 6 further illustrates the performance across subsets. A clear trend emerges: male voices achieve higher STOI and ESTOI scores, indicating better intelligibility and robustness to noise. This advantage can be attributed to their lower fundamental frequencies, which are less prone to distortion. Conversely, female voices obtain higher PESQ scores, reflecting a perceptual impression of clarity and naturalness, despite being more sensitive to high-frequency noise. Taken together, these results highlight a complementary trade-off: male voices tend to preserve intelligibility under degradation, while female voices yield more natural perceptual quality. The latent representations learned by the audio autoencoder are further visualized in Figure 6, which compares the Mel-spectrograms of the ground truth (a) and the reconstructed output (b). While the reconstructed spectrogram exhibits noticeable distortions, its structural similarity to the ground truth indicates that the latent space successfully retains the essential spectral-temporal patterns of speech. This confirms that, although not optimized for perfect audio reconstruction, the autoencoder effectively encodes information-rich latent features that are adequate for subsequent mapping from visual input.

Table 6. Result of Audio Model

Speaker | PESQ | STOI | ESTOI |

P06 (m) | 1.271 | 0.6646 | 0.4 |

P04 (m) | 1.272 | 0.6795 | 0.3924 |

P08 (f) | 1.337 | 0.6195 | 0.3483 |

P03 (f) | 1.382 | 0.5836 | 0.3856 |

Male | 1.45 | 0.7445 | 0.5099 |

Female | 1.465 | 0.6825 | 0.4535 |

|

|

(a) | (b) |

Figure 6. Mel-Spectrogram Representation for (a) Ground Truth (b) Prediction

- Visual Model

The audio autoencoder established in the earlier stage of this study provided a meaningful latent speech space that captures essential spectral–temporal patterns of speech. This latent representation serves as the target domain for mapping from visual input. Building on this foundation, the performance of the visual models was evaluated, with the task of predicting these latent features directly from sequences of lip movements. Four encoder variants were implemented on the LUMINA dataset: LSTM, Bi-LSTM, Bi-LSTM with 4-head attention, and Bi-LSTM with 8-head attention. Table 7 summarizes the PESQ, STOI, and ESTOI results across both individual speakers and multi-speaker subsets.

Table 7. PESQ, STOI, ESTOI for Visual Encoder

Speaker | LSTM | Bi-LSTM | Bi-LSTM + 4-head Attention | Bi-LSTM + 8-head Attention |

PESQ | STOI | ESTOI | PESQ | STOI | ESTOI | PESQ | STOI | ESTOI | PESQ | STOI | ESTOI |

P06(m) | 1.0323 | 0.0582 | 0.3133 | 1.163 | 0.5352 | 0.3399 | 1.153 | 0.5248 | 0.3273 | 1.152 | 0.5310 | 0.3341 |

P04(m) | 1.0326 | 0.0429 | 0.3019 | 1.180 | 0.5598 | 0.3177 | 1.183 | 0.5614 | 0.3112 | 1.118 | 0.4119 | 0.3193 |

P08(f) | 1.0619 | 0.0794 | 0.3233 | 1.272 | 0.5310 | 0.3443 | 1.272 | 0.5259 | 0.3423 | 1.262 | 0.5297 | 0.3449 |

P03(f) | 1.0322 | 0.0433 | 0.2172 | 1.218 | 0.4526 | 0.2982 | 1.209 | 0.4457 | 0.2949 | 1.203 | 0.4301 | 0.2825 |

Male | 1.0319 | 0.4904 | 0.2518 | 1.152 | 0.5309 | 0.2904 | 1.150 | 0,5318 | 0.2889 | 1.154 | 0.5354 | 0.2934 |

Female | 1.1711 | 0.5850 | 0.4023 | 1.205 | 0.6105 | 0.4308 | 1.214 | 0.6113 | 0.4329 | 1.210 | 0.6119 | 0.4330 |

A distinct difference is evident between male and female voices. Female subsets achieve higher PESQ scores, reflecting greater perceptual clarity, while male subsets obtain higher STOI and ESTOI scores, indicating stronger intelligibility due to their lower fundamental frequencies [59][60]. Architecturally, the baseline LSTM performs the worst, as illustrated by the P06 subset, where STOI is only 0.0582. The introduction of Bi-LSTM substantially improves intelligibility across all subsets, confirming the benefit of bidirectional temporal modeling.

The addition of attention mechanisms provides further advantages in multi-speaker scenarios, particularly in stabilizing intelligibility. For example, STOI in the female subset increases from 0.5850 with LSTM to around 0.6119 with Bi-LSTM + attention. However, the use of 8-head attention does not consistently yield improvements and, in some cases, reduces performance. A notable case is the P03 (female) subset, where ESTOI decreases from 0.2982 with Bi-LSTM to 0.2825 with Bi-LSTM + 8-head attention, suggesting that excessive attention heads may dilute focus and destabilize predictions.

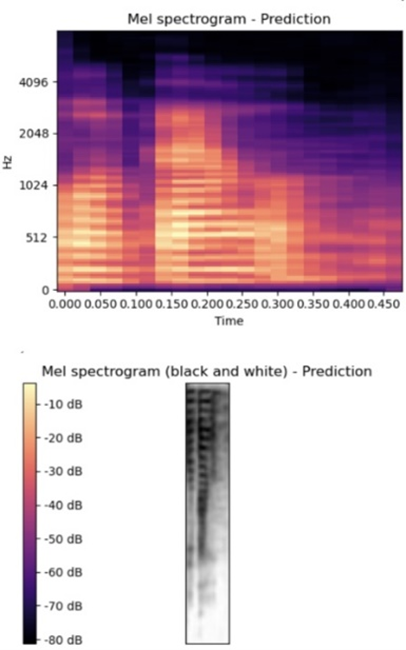

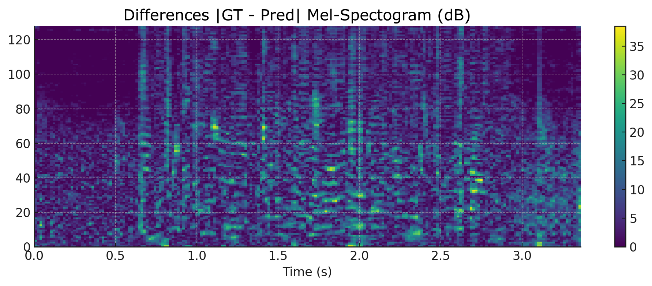

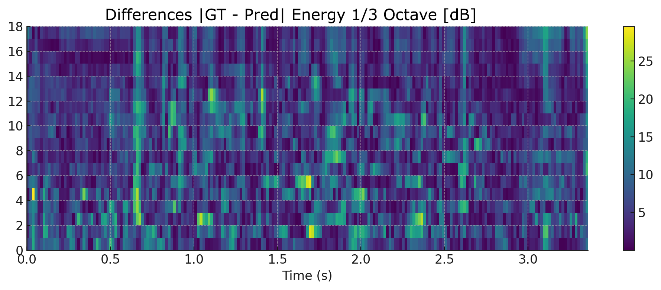

Among the individual subsets, P03 (female) was selected for closer inspection, as it represents the most notable decline when increasing the number of attention heads. This subset, therefore, provides a concrete example to illustrate how over-parameterization in attention design can negatively impact spectral alignment and intelligibility. To further investigate this phenomenon, attention weight distributions were visualized for the Bi-LSTM models with 4-head and 8-head attention. As shown in Figure 7, the 4-head configuration produces sharper and more diagonal attention patterns, indicating that each head consistently attends to temporally aligned and complementary regions of the input sequence. In contrast, the 8-head configuration exhibits more diffuse and overlapping patterns, suggesting that the additional heads fail to provide new discriminative information.

Figure 7. Visualization of Average Attention Distributions in Bi-LSTM with 4-Head and 8-Head Attention

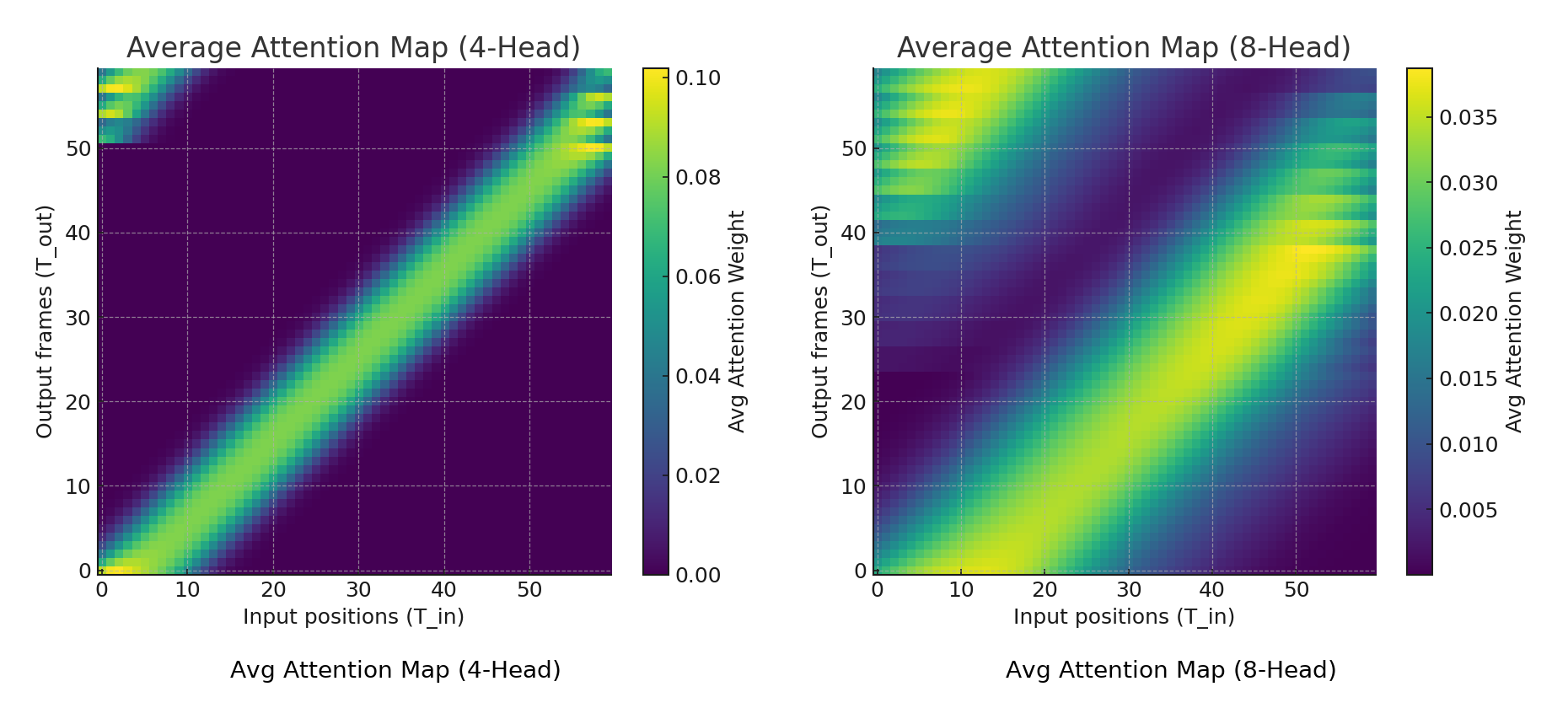

Visual inspection of attention distributions in this case reveals that the use of eight heads tends to spread the focus too evenly across temporal segments, reducing the model’s ability to emphasize the most informative lip movements. This diluted focus correlates with the observed drop in ESTOI and highlights how architectural complexity can sometimes hinder, rather than enhance, performance. These findings are reinforced by STOI analysis, which consistently yields values below the intelligibility threshold of 0.75, indicating degraded clarity under certain conditions. Figure 8 illustrates an example from the P03 subset, comparing the ground truth and predicted outputs through waveform, mel-spectrogram, and energy representations. The comparison shows that the predicted signal exhibits weakened formant structures and shifted spectral transitions, leading to inconsistent envelope alignment.

Figure 8. Waveform, Mel-Spectrogram, Energy Representation for (a) Ground Truth (b) Prediction

STOI itself is a mathematical measure that compares the short-term spectral representations of the ground truth and predicted signals. The process begins with waveform alignment, followed by transformation into the frequency domain using the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT). Spectral energy is then projected onto auditory-inspired frequency bands, and energy envelopes are extracted for each band across frames. Correlations between ground truth and predicted envelopes are computed frame by frame and averaged into a single STOI score. High correlation indicates good alignment, whereas deviations such as weakened formants, frequency shifts, or temporal misalignment reduce correlation. In the case of P03 with Bi-LSTM + 8-head attention, these deviations lowered the frame-wise correlations substantially, producing an overall STOI score of 0.2825—well below the accepted intelligibility threshold of 0.75. This demonstrates that although the generated speech may still be partially understandable to human perception, the algorithm penalizes the lack of spectral correspondence.

As shown in Figure 9, the predicted mel-spectrogram deviates from the ground truth in several time–frequency regions, particularly in formant transitions. These inconsistencies further reduce frame-wise correlation and explain why the P03 subset, although producing speech that remains somewhat intelligible to human listeners, still yielded STOI scores far below the 0.75 threshold under the Bi-LSTM + 8-head attention model. Taken together, the results in Table 6 confirm that Bi-LSTM remains the most stable and effective configuration overall, while attention mechanisms provide limited benefits and may even be detrimental when over-parameterized. Nevertheless, these conclusions are based solely on objective evaluations. To obtain a more comprehensive perspective, they must be complemented by subjective evaluation through the Mean Opinion Score (MOS), which captures how human listeners perceive the synthesized speech.

|

|

(a) | (b) |

Figure 9. Heatmap Differences in (a) Mel-Spectrogram and (b) Energy

- Mean Opinion Score (MOS)

In addition to objective evaluation, a subjective assessment was conducted using the Mean Opinion Score (MOS) test to measure perceptual quality as judged by human listeners. Forty respondents participated in the evaluation, each of whom was asked to rate the generated speech samples on a five-point scale ranging from 0 (completely unintelligible) to 5 (highly clear and intelligible). Each participant was presented with samples generated from all four model variants (LSTM, Bi-LSTM, Bi-LSTM with 4-head attention, and Bi-LSTM with 8-head attention) across all dataset subsets, ensuring a comprehensive evaluation of both single-speaker and multi-speaker conditions. The results in Table 8 reveal a clear and progressive trend: as the model architecture becomes more advanced, perceptual ratings improve across all subsets. The baseline LSTM model consistently received the lowest MOS values, reflecting its limited ability to capture temporal dependencies and produce natural-sounding speech. The Bi-LSTM variant provided substantial improvements, underscoring the advantage of bidirectional temporal modeling. The addition of attention mechanisms further enhanced perceptual quality, with the Bi-LSTM + 8-head attention model achieving the highest MOS scores across both individual and multi-speaker datasets. Notably, the improvement was more pronounced in the female subset, which reached an average MOS of 4.0, compared to 3.6 in the male subset.

These findings also highlight gender-related differences in perceptual preference: synthesized female voices consistently received higher MOS ratings than their male counterparts. This trend aligns with the objective evaluation presented in Table 7, where female voices achieved higher PESQ scores, reflecting perceptual clarity, while male voices performed better in intelligibility metrics. The MOS results confirm that listeners preferred outputs with clearer perceptual quality, reinforcing the importance of spectral characteristics in shaping subjective judgments. While the convergence between objective metrics and subjective MOS ratings strengthens confidence in the overall effectiveness of the proposed models, it remains necessary to establish whether the observed differences are statistically significant. Descriptive improvements, such as the consistent gains of Bi-LSTM over LSTM or the higher MOS achieved by attention-based models, might still occur by chance. To address this, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was employed as a non-parametric method suitable for paired data across model configurations. This statistical validation ensures that the improvements observed are not only perceptually meaningful but also statistically reliable, providing a stronger foundation for concluding that the proposed architectural enhancements genuinely contribute to more effective lip-to-speech synthesis.

Table 8. Mean Opinion Score (MOS) across Models and Subsets

Subset | LSTM | Bi-LSTM | Bi-LSTM + 4 Head Attention | Bi-LSTM + 8 Head Attention |

P06(m) | 1.8 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 3.3 |

P04(m) | 1.7 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 3.2 |

P08(f) | 2.2 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 3.7 |

P03(f) | 1.9 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 3.5 |

Male | 2.0 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 3.6 |

Female | 2.5 | 3.3 | 3.7 | 4.0 |

- Statistical Significance Analysis (Wilcoxon Test)

To further validate the performance differences observed across the four visual models, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was conducted using the PESQ, STOI, and ESTOI metrics. The results are summarized in Table 9. The analysis indicates that all three enhanced models, Bi-LSTM, Bi-LSTM with 4-head attention, and Bi-LSTM with 8-head attention, performed significantly better than the baseline LSTM on PESQ and STOI (p < 0.05). These findings confirm that bidirectional temporal modeling, as well as the integration of attention mechanisms, provides substantial improvements over the conventional LSTM baseline. With respect to ESTOI, significant improvements were also observed when comparing LSTM with Bi-LSTM and Bi-LSTM with 4-head attention, whereas the comparison between LSTM and Bi-LSTM with 8-head attention did not achieve statistical significance. This outcome suggests that while attention generally contributes to intelligibility, increasing the number of attention heads may introduce variability that reduces consistency in capturing fine-grained spectral–temporal details.

By contrast, pairwise comparisons among the Bi-LSTM variants (Bi-LSTM vs. Bi-LSTM + 4-head, Bi-LSTM vs. Bi-LSTM + 8-head, and Bi-LSTM + 4-head vs. Bi-LSTM + 8-head) yielded no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) across any of the three metrics. These results indicate that once bidirectional processing is introduced, the incremental gains from adding multi-head attention are not sufficiently large to be distinguished statistically, even though numerical trends suggest slight improvements in certain cases. Overall, the Wilcoxon analysis reinforces the conclusion that the major performance leap occurs in the transition from LSTM to Bi-LSTM, which consistently improves both perceptual quality and intelligibility. Meanwhile, the addition of multi-head attention contributes to perceptual stability and robustness in multi-speaker contexts, as reflected in MOS results, but does not yield statistically significant gains beyond the bidirectional baseline.

Table 9. Wilcoxon Results for Pairwise Model Comparisons Across PESQ, STOI, and ESTOI

Comparison | PESQ (p-value) | STOI (p-value) | ESTOI (p-value) |

LSTM vs. Bi-LSTM | 0.031 (S) | 0.031 (S) | 0.031 (S) |

LSTM vs. Bi-LSTM + 4-Head | 0.031 (S) | 0.031 (S) | 0.031 (S) |

LSTM vs. Bi-LSTM + 8-Head | 0.031 (S) | 0.031 (S) | 0.438 (NS) |

Bi-LSTM vs. Bi-LSTM + 4-Head | 0.688 (NS) | 0.438 (NS) | 0.156 (NS) |

Bi-LSTM vs. Bi-LSTM + 8-Head | 0.156 (NS) | 0.438 (NS) | 0.438 (NS) |

Bi-LSTM + 4-Head vs. 8-Head | 0.125 (NS) | 1.000 (NS) | 1.000 (NS) |

- CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrates the feasibility of lip-to-speech synthesis for Bahasa Indonesia using a two-stage pipeline with an audio autoencoder and visual encoders. Quantitative evaluations revealed that while the best-performing configuration, Bi-LSTM with attention, achieved improvements over the baseline LSTM—reaching PESQ 1.465, STOI 0.7445, and ESTOI 0.5099—it still fell below the generally accepted intelligibility threshold of 0.75. The results confirm that bidirectional temporal modeling and attention mechanisms can enhance perceptual clarity and stability, particularly in multi-speaker conditions, yet excessive complexity, as in the 8-head variant, can reduce intelligibility.

Beyond its methodological contribution, this study provides an initial benchmark for Bahasa Indonesia, a low-resource language that has received little attention in prior lip-to-speech research. The findings reveal both the opportunities and challenges of applying multimodal learning to languages with rich syllabic variation and limited datasets. Practically, the ability to generate speech from silent video has direct implications for assistive technologies in Indonesia, such as tools for individuals with aphonia or hearing impairment, as well as applications in education, media accessibility, and communication under noisy conditions.

Future work should focus on expanding speaker diversity, adopting larger-scale multimodal corpora, and exploring more advanced architectures such as transformers or diffusion-based models to better capture spectral–temporal alignment and raise intelligibility scores above the 0.75 threshold.

Acknowledgement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. However, it was supported by the Institut Sains dan Teknologi Terpadu Surabaya, which provided the necessary equipment for the recording process, along with laboratory assistants and several staff members who participated as speakers in the dataset creation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

REFERENCES

- D. J. Lewkowicz dan A. H. Tift, “Infants Deploy Selective Attention to the Mouth of a Talking Face When Learning Speech,” In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), vol. 109, no. 5, pp. 1431-1436, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1114783109.

- G. Li, M. Fu, M. Sun, X. Liu dan B. Zheng, “A Facial Feature and Lip Movement Enhanced Audio-Visual Speech Separation Model,” MDPI Sensor, vol. 23, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/s23218770.

- J. S. Chung dan A. Zisserman, “Lip reading in the wild,” In Asian Conference on Computer Vision (ACCV), pp. 87-103, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54184-6_6.

- A. Adler, V. Emiya, M. G. Jafari, M. Elad, R. Gribonval dan M. D. Plumbley, “Audio Inpainting,” IEEE Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 922 - 932, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1109/TASL.2011.2168211.

- D. Rethage, J. Pons dan X. Serra, “A Wavenet for Speech Denoising,” In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), pp. 5069-5073, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP.2018.8462417.

- H. Shi, X. Shi, and S. Dogan, “Speech Inpainting Based on Multi-Layer Long Short-Term Memory Networks,” Future Internet, vol. 16, no. 2, p. 63, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/fi16020063.

- G. Tauböck, S. Rajbamshi and P. Balazs, "Dictionary Learning for Sparse Audio Inpainting," in IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Signal Processing, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 104-119, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTSP.2020.3046422.

- K. R. Prajwal, R. Mukhopadhyay, V. P. Namboodiri and C. V. Jawahar, "Learning Individual Speaking Styles for Accurate Lip to Speech Synthesis," 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 13793-13802, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.01381.

- D. Michelsanti, O. Slizovskaia, G. Haro dan J. Jensen, “Vocoder-Based Speech Synthesis from Silent Videos,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.02541, 2020, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2004.02541.

- Z. Niu and B. Mak, "On the Audio-visual Synchronization for Lip-to-Speech Synthesis," 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), pp. 7809-7818, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV51070.2023.00721.

- Z. Dong, Y. Xu, A. Abel, and D. Wang, “Lip2Speech: lightweight multi-speaker speech reconstruction with gabor features,” Applied Sciences, vol. 14, no. 2, p. 798, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/app14020798.

- R. C. Zheng, Y. Ai dan Z. H. Ling, “Speech Reconstruction from Silent Lip and Tongue Articulation by Diffusion Models and Text-Guided Pseudo Target Generation,” In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, pp. 6559-6568, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1145/3664647.3680770.

- J. Li, C. Li, Y. Wu and Y. Qian, "Unified Cross-Modal Attention: Robust Audio-Visual Speech Recognition and Beyond," in IEEE/ACM Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing, vol. 32, pp. 1941-1953, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/TASLP.2024.3375641.

- S. Ghosh, S. Sarkar, S. Ghosh, F. Zalkow dan N. D. Jana, “Audio-Visual Speech Synthesis Using Vision Transformer–Enhanced Autoencoders,” Applied Intelligence, vol. 54, no. 6, pp. 4507-4524, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10489-024-05380-7.

- N. Sahipjohn, N. Shah, V. Tambrahalli and V. Gandhi, "RobustL2S: Speaker-Specific Lip-to-Speech Synthesis exploiting Self-Supervised Representations," 2023 Asia Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC), Taipei, Taiwan, 2023, pp. 1492-1499, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/APSIPAASC58517.2023.10317357.

- Y. Liang, F. Liu, A. Li, X. Li dan C. Zheng, “NaturalL2S: End-to-End High-quality Multispeaker Lip-to-Speech Synthesis with Differential Digital Signal Processing,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.12002, 2025, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2502.12002.

- R. Mira, A. Haliassos, S. Petridis, B. W. Schuller, and M. Pantic, “Svts: Scalable video-to-speech synthesis,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.02058, 2022, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2205.02058.

- H. Akbari, H. Arora, L. Cao and N. Mesgarani, "Lip2Audspec: Speech Reconstruction from Silent Lip Movements Video," 2018 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), pp. 2516-2520, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP.2018.8461856.

- Y. Yemini, A. Shamsian, L. Bracha, S. Gannot, and E. Fetaya, “Lipvoicer: Generating speech from silent videos guided by lip reading,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.03258, 2023, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2306.03258.

- J. Choi, M. Kim, and Y. M. Ro, “Intelligible lip-to-speech synthesis with speech units,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.19603, 2023, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2305.19603.

- T. Kefalas, Y. Panagakis, and M. Pantic, “Audio-visual video-to-speech synthesis with synthesized input audio,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.16584, 2023, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2307.16584.

- A. P. Wibawa et al., “Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM) Hourly Energy Forecasting,” In E3S Web of Conferences, vol. 501, p. 01023, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202450101023.

- B. Fan, L. Xie, S. Yang, L. Wang dan F. K. Soong, “A deep bidirectional LSTM approach for video-realistic talking head,” Multimedia Tools and Applications, vol. 75, no. 9, pp. 5287-5309, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-015-2944-3.

- H. Wang, F. Yu, X. Shi, Y. Wang, S. Zhang and M. Li, "SlideSpeech: A Large Scale Slide-Enriched Audio-Visual Corpus," ICASSP 2024 - 2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), pp. 11076-11080, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP48485.2024.10448079.

- N. Harte and E. Gillen, "TCD-TIMIT: An Audio-Visual Corpus of Continuous Speech," in IEEE Transactions on Multimedia, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 603-615, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2015.2407694.

- A. Ephrat et al., “Looking to listen at the cocktail party: A speaker-independent audio-visual model for speech separation,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.03619, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1145/3197517.3201357.

- P. Ma, A. Haliassos, A. Fernandez-Lopez, H. Chen, S. Petridis and M. Pantic, "Auto-AVSR: Audio-Visual Speech Recognition with Automatic Labels," ICASSP 2023 - 2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), pp. 1-5, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP49357.2023.10096889.

- E. R. Setyaningsih, A. N. Handayani, W. S. G. Irianto, Y. Kristian and C. T. S. L. Chen, “LUMINA: Linguistic unified multimodal Indonesian natural audio-visual dataset,” Data in Brief, vol. 54, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2024.110279.

- S. Deshpande, K. Shirsath, A. Pashte, P. Loya, S. Shingade, and V. Sambhe, “A Comprehensive Survey of Advancement in Lip Reading Models: Techniques and Future Directions,” IET Image Processing, vol. 19, no. 1, p. e70095, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1049/ipr2.70095.

- T. Afouras, J. S. Chung dan A. Zisserman, “LRS3-TED: a large-scale dataset for visual speech recognition,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.00496, 2018, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1809.00496.

- C. T. S. L. Chen, Y. Kristian and E. R. Setyaningsih, "Audio-Visual Speech Reconstruction for Communication Accessibility: A ConvLSTM Approach to Indonesian Lip-to-Speech Synthesis," 2025 International Conference on Data Science and Its Applications (ICoDSA), pp. 770-776, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICoDSA67155.2025.11157146.

- T. Afouras, J. S. Chung, A. Senior, O. Vinyals and A. Zisserman, "Deep Audio-Visual Speech Recognition," in IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, vol. 44, no. 12, pp. 8717-8727, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2018.2889052.

- A. Rachman, R. Hidayat and H. A. Nugroho, "Analysis of the Indonesian vowel /e/ for lip synchronization animation," 2017 4th International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Computer Science and Informatics (EECSI), pp. 1-5, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1109/EECSI.2017.8239114.

- A. Kurniawan and S. Suyanto, "Syllable-Based Indonesian Lip Reading Model," 2020 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology (ICoICT), pp. 1-6, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICoICT49345.2020.9166217.

- S. Recanatesi, M. Farrell, M. Advani, T. Moore, G. Lajoie, and E. Shea-Brown, “Dimensionality compression and expansion in deep neural networks,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.00443, 2019, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1906.00443.

- R. Yadav, A. Sardana, V. P. Namboodiri and R. M. Hegde, "Speech Prediction in Silent Videos Using Variational Autoencoders," ICASSP 2021 - 2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Toronto, ON, Canada, 2021, pp. 7048-7052, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP39728.2021.9414040.

- C. B. Vennerød, A. Kjærran, and E. S. Bugge, “Long short-term memory RNN,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.06756, 2021, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2105.06756.

- K. Dedes, A. B. P. Utama, A. P. Wibawa, A. N. Afandi, A. N. Handayani dan L. Hernandez, “Neural Machine Translation of Spanish-English Food Recipes Using LSTM,” JOIV: International Journal on Informatics Visualization, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 290-297, 2022, https://doi.org/10.30630/joiv.6.2.804.

- W. T. Handoko, Muladi dan A. N. Handayani, “Forecasting Solar Irradiation on Solar Tubes Using the LSTM Method and Exponential Smoothing,” Jurnal Ilmiah Teknik Elektro Komputer dan Informatika, vol. 9, pp. 649-660, 2023, https://doi.org/10.26555/jiteki.v9i3.26395.

- A. Graves and J. Schmidhuber, "Framewise phoneme classification with bidirectional LSTM networks," Proceedings. 2005 IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, 2005., pp. 2047-2052 vol. 4, 2005, https://doi.org/10.1109/IJCNN.2005.1556215.

- K. Greff, R. K. Srivastava, J. Koutník, B. R. Steunebrink and J. Schmidhuber, "LSTM: A Search Space Odyssey," in IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, vol. 28, no. 10, pp. 2222-2232, Oct. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2016.2582924.

- K. Cho, B. Van Merriënboer, D. Bahdanau, and Y. Bengio, “On the properties of neural machine translation: Encoder-decoder approaches,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1259, 2014, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1409.1259.

- M. T. Luong, H. Pham and C. D. Manning, “Effective approaches to attention-based neural machine translation,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1508.04025, 2015, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1508.04025.

- C. Subakan, M. Ravanelli, S. Cornell, M. Bronzi and J. Zhong, "Attention Is All You Need In Speech Separation," ICASSP 2021 - 2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), pp. 21-25, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP39728.2021.9413901.

- C. Suardi, A. N. Handayani, R. A. Asmara, A. P. Wibawa, L. N. Hayati and H. Azis, "Design of Sign Language Recognition Using E-CNN," 2021 3rd East Indonesia Conference on Computer and Information Technology (EIConCIT), pp. 166-170, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/EIConCIT50028.2021.9431877.

- G. Brauwers and F. Frasincar, "A General Survey on Attention Mechanisms in Deep Learning," in IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 3279-3298, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/TKDE.2021.3126456.

- M. R. A. R. Maulana and M. I. Fanany, "Sentence-level Indonesian lip reading with spatiotemporal CNN and gated RNN," 2017 International Conference on Advanced Computer Science and Information Systems (ICACSIS), pp. 375-380, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICACSIS.2017.8355061.

- T. Procter and A. Joshi, “Cultural competency in voice evaluation: considerations of normative standards for sociolinguistically diverse voices,” Journal of Voice, vol. 36, no. 6, pp. 793-801, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2020.09.025.

- M. Kim, J. Hong and Y. M. Ro, "Lip-to-Speech Synthesis in the Wild with Multi-Task Learning," ICASSP 2023 - 2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), pp. 1-5, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP49357.2023.10095582.

- A. Ephrat, O. Halperin dan S. Peleg, “Improved Speech Reconstruction from Silent Video,” In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, pp. 455-462, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCVW.2017.61.

- S. Hegde, R. Mukhopadhyay, C. V. Jawahar, and V. Namboodiri, “Towards accurate lip-to-speech synthesis in-the-wild,” In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, pp. 5523-5531, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1145/3581783.3611787.

- K. W. Cheuk, H. Anderson, K. Agres and D. Herremans, "nnAudio: An on-the-Fly GPU Audio to Spectrogram Conversion Toolbox Using 1D Convolutional Neural Networks," in IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 161981-162003, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3019084.

- V. Kazemi dan J. Sullivan, “One Millisecond Face Alignment with an Ensemble of Regression Trees,” In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 1867-1874, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2014.241.

- Y. Zhang, J. Zhang, Q. Wang, and Z. Zhong, “Dynet: Dynamic convolution for accelerating convolutional neural networks,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.10694, 2020, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2004.10694.

- A. W. Rix, J. G. Beerends, M. P. Hollier and A. P. Hekstra, "Perceptual evaluation of speech quality (PESQ)-a new method for speech quality assessment of telephone networks and codecs," 2001 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing. Proceedings (Cat. No.01CH37221), pp. 749-752 vol.2, 2001, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP.2001.941023.

- C. H. Taal, R. C. Hendriks, R. Heusdens and J. Jensen, "A short-time objective intelligibility measure for time-frequency weighted noisy speech," 2010 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, pp. 4214-4217, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP.2010.5495701.

- J J. Jensen and C. H. Taal, "An Algorithm for Predicting the Intelligibility of Speech Masked by Modulated Noise Maskers," in IEEE/ACM Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing, vol. 24, no. 11, pp. 2009-2022, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1109/TASLP.2016.2585878.

- A. Alghamdi and W. -Y. Chan, "Modified ESTOI for improving speech intelligibility prediction," 2020 IEEE Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (CCECE), pp. 1-5, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/CCECE47787.2020.9255677.

- Y. Leung, J. Oates, V. Papp, and S. P. Chan, ‘Speaking fundamental frequencies of adult speakers of Australian English and effects of sex, age, and geographical location,” Journal of Voice, vol. 36, no. 3, p. 434-e1, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2020.06.014.

- A. Serrurier and C. Neuschaefer-Rube, “Morphological and acoustic modeling of the vocal tract,” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, vol. 153, no. 3, pp. 1867-1886, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0017356.

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

| Eka Rahayu Setyaningsih She earned her Bachelor’s degree in Informatics in 2010 from Sekolah Tinggi Teknik Surabaya, Indonesia. She then completed her Master’s degree in Information Technology in 2014 at the same institution. She is currently a university lecturer at Institut Sains dan Teknologi Terpadu Surabaya, Indonesia. Her current research focuses on lip-to-speech synthesis for Indonesian audio-visual data, with broader interests in speech processing, multimodal learning, and artificial intelligence. Email: eka.rahayu.2205349@students.um.ac.id ORCID: 0009-0009-5334-090X |

|

|

| Anik Nur Handayani She received her Master’s degree in Electrical Engineering from Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember (ITS), Surabaya, Indonesia, in 2008, and her Doctoral degree in Science and Advanced Engineering from Saga University, Japan. She is currently a lecturer at Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia. Her research interests include image processing, biomedical signal analysis, artificial intelligence, machine learning, deep learning, computer vision, and assistive technologies. Email: aniknur.ft@um.ac.id ORCID: 0009-0003-0767-8471 |

|

|

| Wahyu Sakti Gunawan Irianto He received his Master’s degree in Computer Science from Universitas Indonesia in 1997 and his Doctoral degree in Computer Science. He is currently a senior lecturer in the Department of Electrical Engineering at Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia. His research interests include computer science education, educational technology, intelligent systems, embedded and microcontroller applications, and digital systems. He has also contributed to various projects, including the development of interactive learning modules based on Arduino and multimodal dataset research in the LUMINA project. Email: wahyu.sakti.ft@um.ac.id ORCID: 0009-0002-5609-4045 |

|

|

| Yosi Kristian He obtained his bachelor’s degree in Computer Science and master’s degree in Information Technology from Sekolah Tinggi Teknik Surabaya in 2004 and 2008, respectively. In 2018, he earned his Ph.D. from the Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember (ITS) in Surabaya, Indonesia. In 2015, he was a research student at Osaka City University. Since 2004, he has been a faculty member at Institut STTS, currently serving as an Associate Professor and Head of the Department of Informatics. His research interests include Machine Learning, Deep Learning, Artificial Intelligence, and Computer Vision. Email: yosi@stts.edu ORCID: 0000-0003-1082-5121 |

Eka Rahayu Setyaningsih (Bi-LSTM and Attention-based Approach for Lip-To-Speech Synthesis in Low-Resource Languages: A Case Study on Bahasa Indonesia)