ISSN: 2685-9572 Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro

Vol. 7, No. 4, December 2025, pp. 823-841

Electrooculography and Camera-Based Control of a Four-Joint Robotic Arm for Assistive Tasks

Muhammad Ilhamdi Rusydi 1, Andre Paskah Gultom 1, Adam Jordan 1, Rahmad Novan Nurhadi 1, Noverika Windasari 2, Minoru Sasaki 3, Ridza Azri Ramlee 4

1 Department of Electrical Engineering, Universitas Andalas, Indonesia

2 Medical Faculty, Universitas Andalas, Indonesia

3 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Gifu University, Japan

4 Fakulti Kejuruteraan Elektronik dan Kejuruteraan Komputer (FKEKK), Universiti Teknikal Malaysia Melaka (UTeM), Melaka, Malaysia

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 20 July 2025 Revised 13 October 2025 Accepted 17 November 2025 |

|

Individuals with severe motor impairments face challenges in performing daily manipulation tasks independently. Existing assistive robotic systems show limited accuracy (typically 85–92%) and low intuitive control, requiring extensive training. This study presents a control system integrating electrooculography (EOG) signals with real-time computer vision feedback for natural, high-precision control of a 4-degrees-of-freedom (4-DOF) robotic manipulator in assistive applications. The system uses an optimized K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) algorithm to classify six eye-movement categories with computational efficiency and real-time performance. Computer-vision modules map object coordinates and provide feedback integrated with inverse kinematics for positioning. Validation with 10 able-bodied participants (aged 18–22) employed standardized protocols under controlled laboratory conditions. The KNN classifier achieved 98.17% accuracy, 98.47% true-positive and 1.53% false-negative rates. Distance-measurement error averaged 1.5 mm (± 1.6 mm). Inverse-kinematics positioning attained sub-millimeter precision with 0.64 mm mean absolute error (MAE) for frontal retrieval and 1.58 mm for overhead retrieval. Operational success rates reached 99.48% for frontal and 97.96% for top-down retrieval tasks. The system successfully completed object detection, retrieval, transport, and placement across ten locations. These findings indicate a significant advancement in EOG-based assistive robotics, achieving higher accuracy than conventional systems while maintaining intuitive user control. The integration shows promising potential for rehabilitation centers and assistive environments, though further validation under diverse conditions, including latency and fatigue, is needed. |

Keywords: Electrooculography-based Control; Assistive Robotics; Human-Robot Interaction; Inverse Kinematics; KNN Classification |

Corresponding Author: Muhammad Ilhamdi Rusydi, Department of Electrical Engineering, Universitas Andalas, Padang, Indonesia. Email: rusydi@eng.unand.ac.id |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: M. I. Rusydi, A. P. Gultom, A. Jordan, R. N. Nurhadi, N. Windasari, M. Sasaki, and R. A. Ramlee, “Electrooculography and Camera-Based Control of a Four-Joint Robotic Arm for Assistive Tasks,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 823-841, 2025, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v7i4.14305. |

- INTRODUCTION

The implementation of robotic systems to aid the elderly and individuals with disabilities in executing daily living activities autonomously has yielded positive outcomes [1]–[7]. This investigation focuses on the development of an EOG-controlled robotic manipulator system designed as an external assistive device for individuals with severe motor impairments who retain ocular control[8]. Robotic manipulators and prosthetic hands share similarities in design and function [8]–[12]. Robot manipulators provide a mechanism to bridge the gap between disabilities marked by the lack of hand function and their environment, thus facilitating individuals with disabilities to proficiently grasp and manipulate objects [9],[13]–[15].

The integration of biosignals into control systems for assistive robotic devices has significantly advanced rehabilitation technologies [16]–[18]. Among various biosignal modalities, Electrooculography (EOG) presents unique advantages for individuals with severe motor impairments, as ocular motor function is often preserved even when limb mobility is completely lost [19][20]. EOG-based control systems translate eye movements into mechanical commands through signal acquisition, processing, and implementation of control strategies [21]–[25]. While alternative modalities such as Electromyography (EMG) have been explored, they require residual muscle function that may not be available in conditions such as advanced amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) or high-level spinal cord injuries [26][27]. Therefore, EOG represents a particularly suitable control interface for the target user population of this study. Conventional assistive control systems typically achieve 85–92% accuracy in laboratory settings [28], establishing the baseline for clinical viability. Recent advances in machine learning and high-density sensing have demonstrated accuracies exceeding 95% in offline evaluations [29]. However, measurable performance gaps persist during real-time closed-loop operation, with accuracy drops of approximately 4% attributed to user adaptation, feedback effects, and context shifts [30].

Despite the promising potential of electrooculography (EOG) as a control modality for human–computer interaction (HCI) and brain–computer interfaces (BCI), its practical adoption is still limited by several challenges. Signal quality issues such as baseline drift, blink and fatigue artifacts, and high inter-subject variability often degrade performance and require extensive calibration [31]–[37]. Real-time responsiveness also remains problematic, as latency between ocular intention and system feedback can disrupt continuous interaction and frustrate users [38]–[42]. Furthermore, scalability is constrained: most EOG applications emphasize coarse binary commands, with relatively little progress toward fine motor decoding, precision manipulation, or seamless transition from 2D to 3D spatial control [43]–[46]. Addressing these limitations requires hybrid approaches that integrate EOG with complementary modalities like SSVEP, EEG, or eye-tracking, alongside innovations in electrode design and edge processing, to enhance robustness, scalability, and usability in real-world assistive and interactive systems [47][48].

Translating EOG-derived commands into precise spatial positioning requires robust inverse kinematics algorithms to calculate joint angles that achieve accurate end-effector placement [49]–[51]. While analytical and numerical solvers are commonly employed, their performance may be constrained by manipulator design or operational velocity requirements [52][53]. The computational complexity inherent in inverse kinematics presents a critical challenge for EOG-based systems, where latency must be minimized to maintain natural interaction [54]–[62]. This computational constraint directly influences the selection of manipulator degrees of freedom (DOF). Three-DOF configurations limit workspace reachability and approach angles, restricting manipulation strategies for activities of daily living [63]. Conversely, six-DOF systems introduce kinematic redundancy that increases computational burden and control complexity, potentially introducing unacceptable delays in real-time EOG control loops where latency critically affects user experience [64]. A four-DOF configuration represents an optimal balance, providing sufficient flexibility for common grasping tasks—including approach angle variation and obstacle avoidance—while maintaining computational tractability for real-time performance [65]–[68]. Recent advancements demonstrate that optimized DOF selection combined with efficient inverse kinematics algorithms can enhance both operational precision and system responsiveness in assistive manipulation applications [69]–[73].

Prior research has demonstrated the feasibility of EOG-based control in assistive applications, yet critical gaps remain in transitioning from coarse control to precision manipulation. Earlier work developed a multi-biosignal manipulator system combining EOG, jaw EMG, and flex sensors, achieving minimal errors in pick-and-place tasks using fuzzy logic controllers [74]. However, this multi-modal approach limits applicability to users with preserved muscle function beyond ocular control—excluding individuals with complete motor paralysis. Subsequent research achieved 98.89% accuracy in EOG-controlled wheelchair navigation through decision tree classification of eye movements and blinks [75]. While demonstrating EOG reliability, wheelchair control addresses fundamentally different requirements than robotic manipulation. Wheelchair navigation relies on discrete directional commands (forward, left, right, stop) with centimeter-level precision and intermittent control actions [76][77]. Conversely, robotic manipulation demands continuous trajectory control in three-dimensional space with millimeter-level precision for successful object grasping and handling [78]. This transition presents significant challenges: increased spatial dimensionality (2D→3D), heightened precision requirements from cm to mm, and continuous vs. discrete control paradigms. These translational challenges motivate the development of enhanced control architectures specifically designed for EOG-based precision manipulation tasks.

To address these identified gaps, the research contributions of this study are threefold. First, we introduce an integration of EOG-based control with a dual-function camera system that not only provides intuitive real-time visual feedback to the user but also enables accurate mapping of object coordinates within the workspace. This integration directly mitigates the cognitive load associated with conventional EOG interfaces, which often lack intuitive interaction. Second, we design and implement a 4-DOF robotic manipulator specifically optimized for EOG-driven assistive grasping. The chosen configuration achieves an effective trade-off between manipulation flexibility and computational efficiency, thereby supporting more complex approach strategies without incurring the processing overhead that typically compromises responsiveness in EOG control loops. Third, we develop a hybrid control architecture that combines eye-movement detection with automated object recognition. This design substantially reduces the precision demands placed on the user by automatically identifying and localizing objects, allowing EOG signals to function primarily as high-level intent commands rather than low-level control inputs. Collectively, these contributions address critical gaps in current approaches by reducing cognitive effort, enhancing control precision, and improving overall system usability. In doing so, this work advances the development of assistive robotic technologies aimed at empowering individuals with severe motor impairments who retain reliable ocular motor function.

This EOG-controlled robotic manipulator system is designed to address the needs of individuals with severe motor impairments affecting hand function but with preserved ocular motor control, including conditions such as advanced ALS, high-level spinal cord injuries, and severe cerebral palsy. The system enables execution of activities of daily living (ADLs) such as object retrieval, manipulation of eating utensils, and handling of personal items. By reducing dependence on caregiver assistance for routine tasks, the system has potential to improve user autonomy and quality of life, which will be evaluated through controlled testing protocols described in subsequent sections.

- MATERIALS AND METHODS

- System Architecture Overview

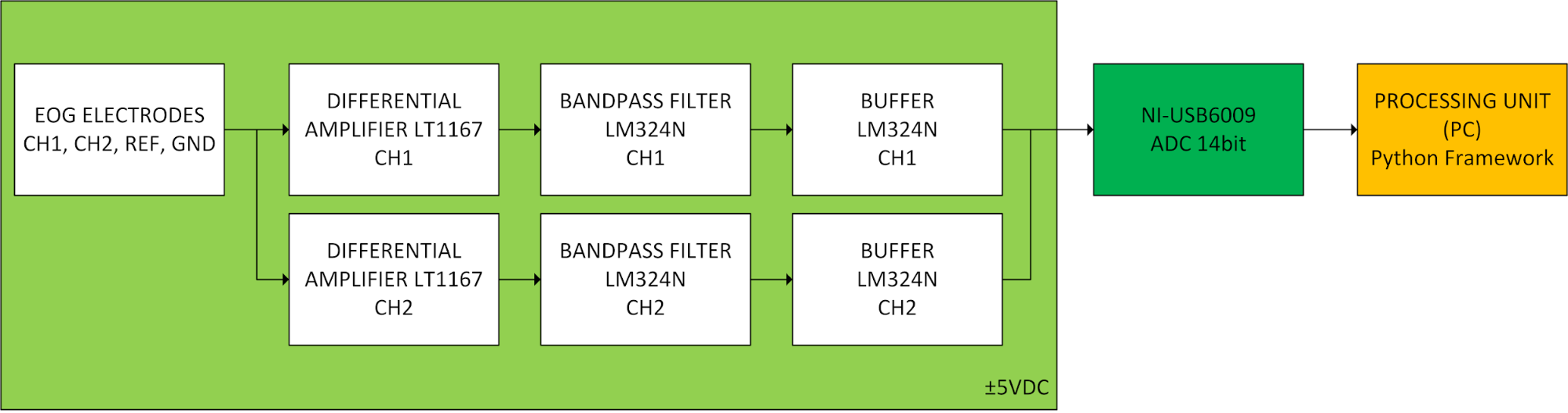

The proposed robotic manipulator control framework integrates all hardware and software components essential for multimodal operation. The system combines an electrooculography (EOG) sensing module for eye movement detection with a vision-based feedback system for real-time spatial awareness. The EOG acquisition circuit, shown in Figure 1, captures ocular biopotentials from two active channels (CH1 and CH2) referenced to ground. Each channel is amplified using a differential instrumentation amplifier (LT1167), filtered through an active bandpass filter (LM324N, 0–10 Hz), and buffered (LM324N) to stabilize the signal before digitization. The fixed-gain design was selected to maintain signal linearity, while periodic recalibration ensured user-specific adaptation. To further enhance long-term signal stability, baseline drift was mitigated through per-trial detrending and periodic recalibration of reference potentials, effectively compensating for low-frequency fluctuations that may occur during prolonged operation. The processed analog signals are then converted to digital form via a National Instruments USB-6009 (14-bit ADC) module and transmitted to the processing unit through a Python-based serial interface. This architecture provides effective noise suppression, baseline-drift compensation, and signal integrity for reliable feature extraction.

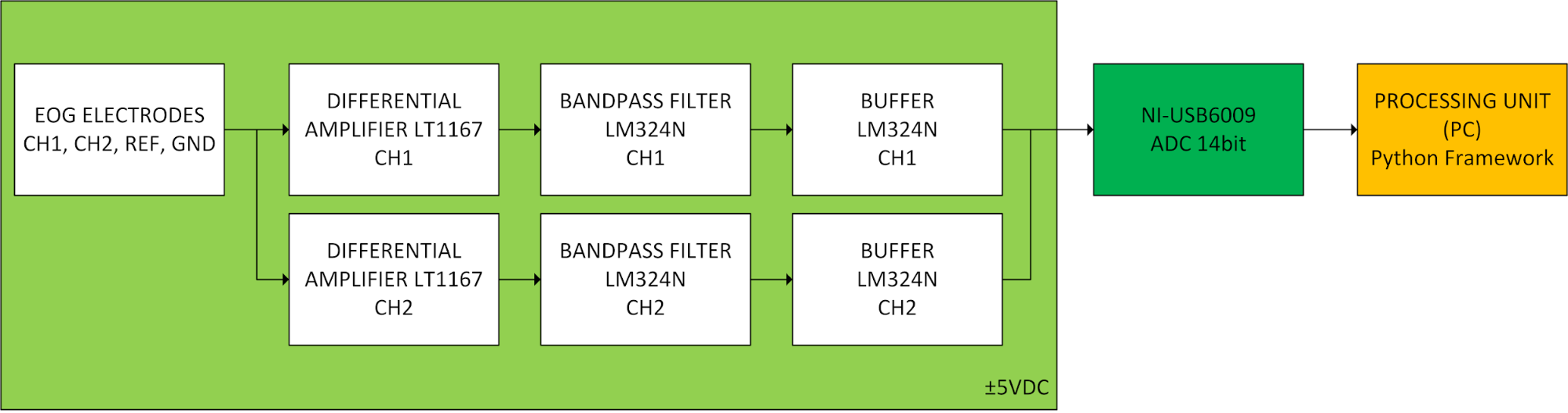

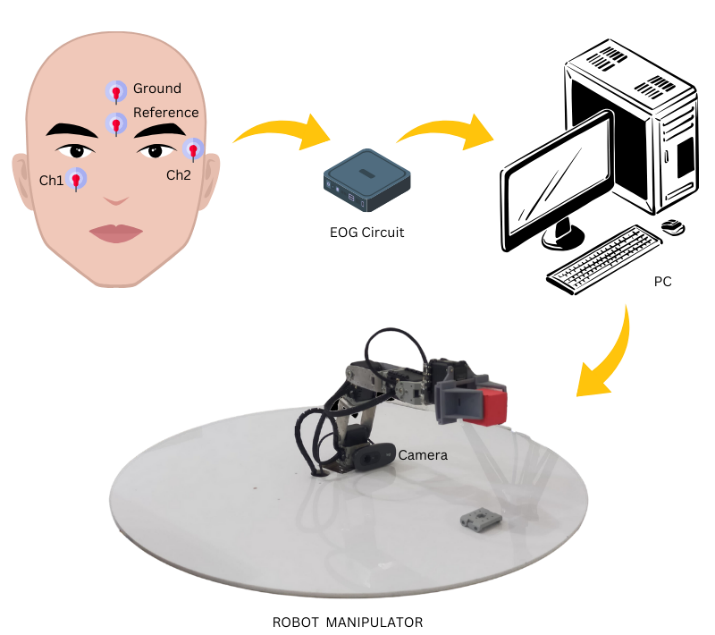

The overall system architecture integrates the EOG module, camera-based vision module, and 4-DOF robotic manipulator under a unified control platform, as illustrated in Figure 2. The EOG signals are interpreted using a K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) classifier to map user gaze and voluntary blinks to corresponding robotic actions, while the vision subsystem provides continuous spatial feedback for object localization and trajectory verification. The robot chassis [79][80] is fabricated with thorough consideration for the sturdiness and minimal weight of the material. The robotic manipulator structure, depicted in Figure 3, comprises four links and corresponding rotational joints configured for optimal workspace flexibility and computational efficiency. The link lengths are defined as  = 90 mm,

= 90 mm,  = 100 mm,

= 100 mm,  = 100 mm, and

= 100 mm, and  = 90 mm. The mechanical chassis is fabricated from 3 mm aluminum for structural rigidity, while the end-effector components are produced from resin of equal thickness to minimize weight. The 4-DOF configuration enables rotation about the z-axis and articulated movement in three-dimensional space, providing sufficient maneuverability for object retrieval and placement tasks without introducing excessive kinematic redundancy.

= 90 mm. The mechanical chassis is fabricated from 3 mm aluminum for structural rigidity, while the end-effector components are produced from resin of equal thickness to minimize weight. The 4-DOF configuration enables rotation about the z-axis and articulated movement in three-dimensional space, providing sufficient maneuverability for object retrieval and placement tasks without introducing excessive kinematic redundancy.

The robot manipulator will manipulate the position of the end effector through rotation on the z-axis. This mechanical configuration affords flexibility of movement in three-dimensional space, wherein each joint is capable of providing specific rotational degrees of freedom. This enables accurate calibration of the end effector's movement with maximum reach. The precisely determined link length configuration will define the robot's working space, its motion capabilities, and its proficiency in handling tasks in different environments. With the combination of mechanical design and EOG signal-based control systems, this manipulator robot is expected to provide an innovative solution in precise and responsive robotic motion control. The integrated design ensures cohesive interaction between sensory input, computational processing, and mechanical execution, forming the foundation for subsequent modules addressing vision-based distance estimation, inverse kinematics computation, and EOG signal classification.

Figure 1. Block diagram of the EOG signal acquisition and conditioning circuit

Figure 2. Overall system architecture for the EOG–vision–based robotic control system

Figure 3. Kinematic Representation of a Robot Manipulator

- Vision-based Distance Measurement Algorithm

The visual data acquisition subsystem employs a Logitech C270 camera mounted at the base of the manipulator to obtain real-time visual feedback for object localization and distance measurement. The optical configuration features a 4 mm focal length and a 4.8 mm × 3.6 mm CMOS sensor, supporting a maximum resolution of 1280 × 720 pixels. These specifications, verified through manufacturer documentation, ensure adequate spatial sampling and image fidelity for the designated workspace. Proper positioning ensures that the resulting image data is of the highest quality and accuracy for future analysis [81][82].

Prior to data acquisition, the camera underwent intrinsic calibration using a checkerboard pattern to correct lens distortion and perspective error. The calibration process produced the intrinsic parameters (focal length, principal point, and distortion coefficients), which were subsequently applied to undistort captured frames and refine the geometric mapping between the real and image spaces. This calibration ensured accurate metric consistency for all subsequent visual computations. Object distance was determined using the pinhole camera model, which defines the proportional relationship between real-world dimensions and their corresponding image projections. The distance  between the camera and the object is given by:

between the camera and the object is given by:

|

| (1) |

where denotes the effective focal length (in pixels),

denotes the effective focal length (in pixels),  represents the actual object height (in millimeters), and

represents the actual object height (in millimeters), and  corresponds to the object height in the captured image (in pixels).

corresponds to the object height in the captured image (in pixels).

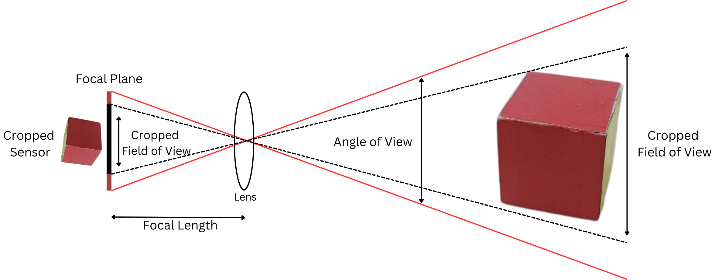

The geometric configuration underlying this relationship is shown in Figure 4, which depicts the projection path from the object through the lens to the focal plane. The model illustrates how focal length, field of view, and object scale interact to determine the perceived image size on the sensor plane. For validation, the algorithm was tested using a red cubic target with known dimensions (30 mm × 30 mm × 30 mm) under uniform illumination (500 lux). Object segmentation was performed in the HSV color space to maintain robust detection across minor lighting variations. The measured distance values were compared against physical measurements obtained from a laser rangefinder to verify accuracy. Although this study utilized a single standardized object, the framework can be extended to multi-object environments through dataset expansion and adaptive feature learning. This vision-based distance estimation algorithm provides the spatial reference input for the manipulator’s inverse kinematics computation, ensuring that the end-effector executes precise positioning within the camera’s calibrated coordinate space.

Figure 4. Geometric representation of the pinhole camera model

- Inverse Kinematics for Robotic Manipulation

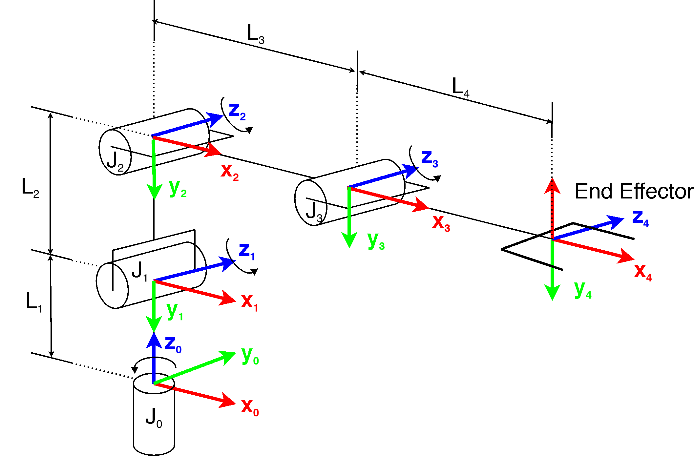

The inverse kinematic equation applies geometric principles to identify the joint angle of the robotic arm necessary for securing the intended end effector position [69],[83][84]. The inverse kinematics formulation determines the joint angles required to position the robotic manipulator’s end effector at a desired spatial coordinate. The 4-DOF configuration was selected to achieve an effective trade-off between workspace dexterity and computational simplicity. Three-DOF manipulators offer limited reachability and constrained approach angles, while six-DOF configurations introduce redundancy that increases solution complexity and control latency. The chosen 4-DOF structure ensures adequate flexibility for assistive manipulation while maintaining computational efficiency for real-time EOG-based control.

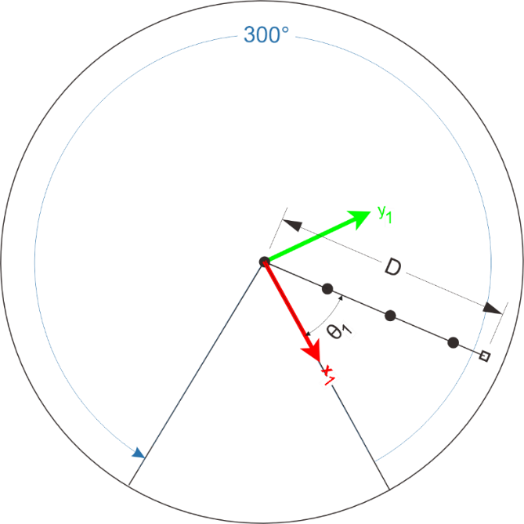

The inverse kinematic problem is decomposed into two planes of motion: the horizontal plane for base rotation ( ) and the vertical plane for reach and orientation (

) and the vertical plane for reach and orientation ( ). This decomposition simplifies the 3D computation while preserving spatial accuracy. The top view of the manipulator, illustrated in Figure 5, defines the geometric relationship for determining the base rotation angle θ₁ required to align the arm toward the target coordinates (

). This decomposition simplifies the 3D computation while preserving spatial accuracy. The top view of the manipulator, illustrated in Figure 5, defines the geometric relationship for determining the base rotation angle θ₁ required to align the arm toward the target coordinates ( ,

,  ). The radial extension D between the manipulator base and the target is calculated using the Euclidean distance, as expressed in (2). The base rotation angle is then computed using trigonometric relationships equation (3) to equation (4). Following the computation of the base rotation angle

). The radial extension D between the manipulator base and the target is calculated using the Euclidean distance, as expressed in (2). The base rotation angle is then computed using trigonometric relationships equation (3) to equation (4). Following the computation of the base rotation angle  in the horizontal plane, the vertical configuration is analyzed to determine the remaining joint angles (

in the horizontal plane, the vertical configuration is analyzed to determine the remaining joint angles ( ,

,  , and

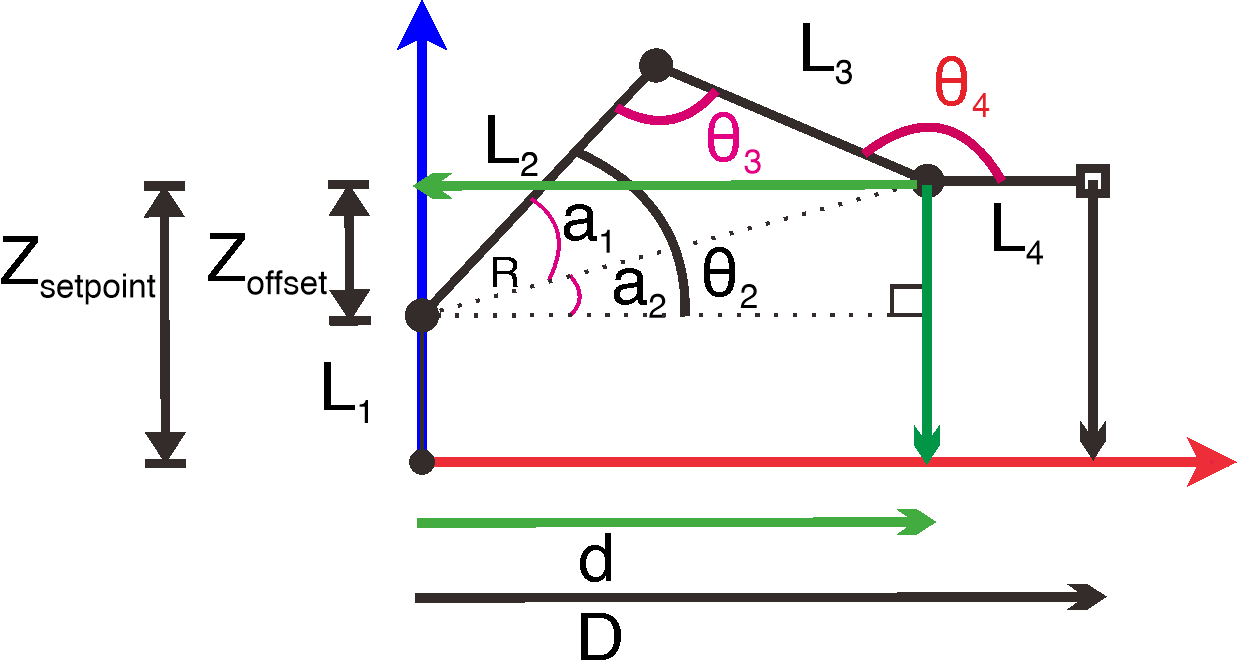

, and  ). The geometric relationships in the z–d plane are depicted in Figure 6, which illustrates the link dimensions (

). The geometric relationships in the z–d plane are depicted in Figure 6, which illustrates the link dimensions ( –

– ), the vertical offset

), the vertical offset  -offset, and the trigonometric parameters used for spatial positioning of the end effector.

-offset, and the trigonometric parameters used for spatial positioning of the end effector.

Figure 5. Top view illustration of robot in work area

Figure 6. Side-view kinematic configuration of the 4-DOF manipulator showing joint angles  and link parameters (

and link parameters ( –

– ) within the z–d plane

) within the z–d plane

The  -axis offset is derived from the target height

-axis offset is derived from the target height  -setpoint by subtracting the base link length

-setpoint by subtracting the base link length  , as shown in equation (5). The resulting planar distance R, representing the distance between joints 2 and 4, is computed using equation (6). The intermediate angles

, as shown in equation (5). The resulting planar distance R, representing the distance between joints 2 and 4, is computed using equation (6). The intermediate angles  and

and  are derived from triangular trigonometry as in equation (7) and equation (8), and used to determine the shoulder angle in equation (9). The elbow and wrist joint angles

are derived from triangular trigonometry as in equation (7) and equation (8), and used to determine the shoulder angle in equation (9). The elbow and wrist joint angles  and

and  are obtained using equation (10) and equation (11), completing the inverse kinematics formulation for the 4-DOF manipulator.

are obtained using equation (10) and equation (11), completing the inverse kinematics formulation for the 4-DOF manipulator.

The above analytical approach ensures that the system can compute inverse kinematics in real time without resorting to iterative numerical solvers, thereby minimizing computational delay. Singularity avoidance and joint-limit constraints were integrated within the control software to prevent configuration lock and mechanical interference. This approach guarantees smooth, stable, and precise end-effector motion consistent with the spatial inputs provided by the vision module.

- EOG Feature Extraction and KNN Classification

After analog preprocessing and digitization through the EOG acquisition circuit, the recorded signals from two channels (CH1 and CH2) were processed in a Python-based environment for segmentation, feature extraction, and classification. The digitized signals were sampled at 250 Hz with 14-bit resolution using the NI-USB6009 module, ensuring sufficient temporal precision for ocular event analysis. Each signal segment corresponding to a single eye movement was isolated using a time-windowing process combined with zero-crossing detection to identify the onset and offset of each event. Feature extraction was performed to represent the temporal and intensity characteristics of the eye movements. Two primary parameters were obtained from each channel: the amplitude ( ) and the duration (

) and the duration ( ). The amplitude represents the maximum deviation from the baseline potential, indicating the strength and polarity of ocular displacement, while the duration corresponds to the time interval between the start and end of the movement, describing its duration. These features were extracted across all movements, including blinks, to provide discriminative inputs for classification.

). The amplitude represents the maximum deviation from the baseline potential, indicating the strength and polarity of ocular displacement, while the duration corresponds to the time interval between the start and end of the movement, describing its duration. These features were extracted across all movements, including blinks, to provide discriminative inputs for classification.

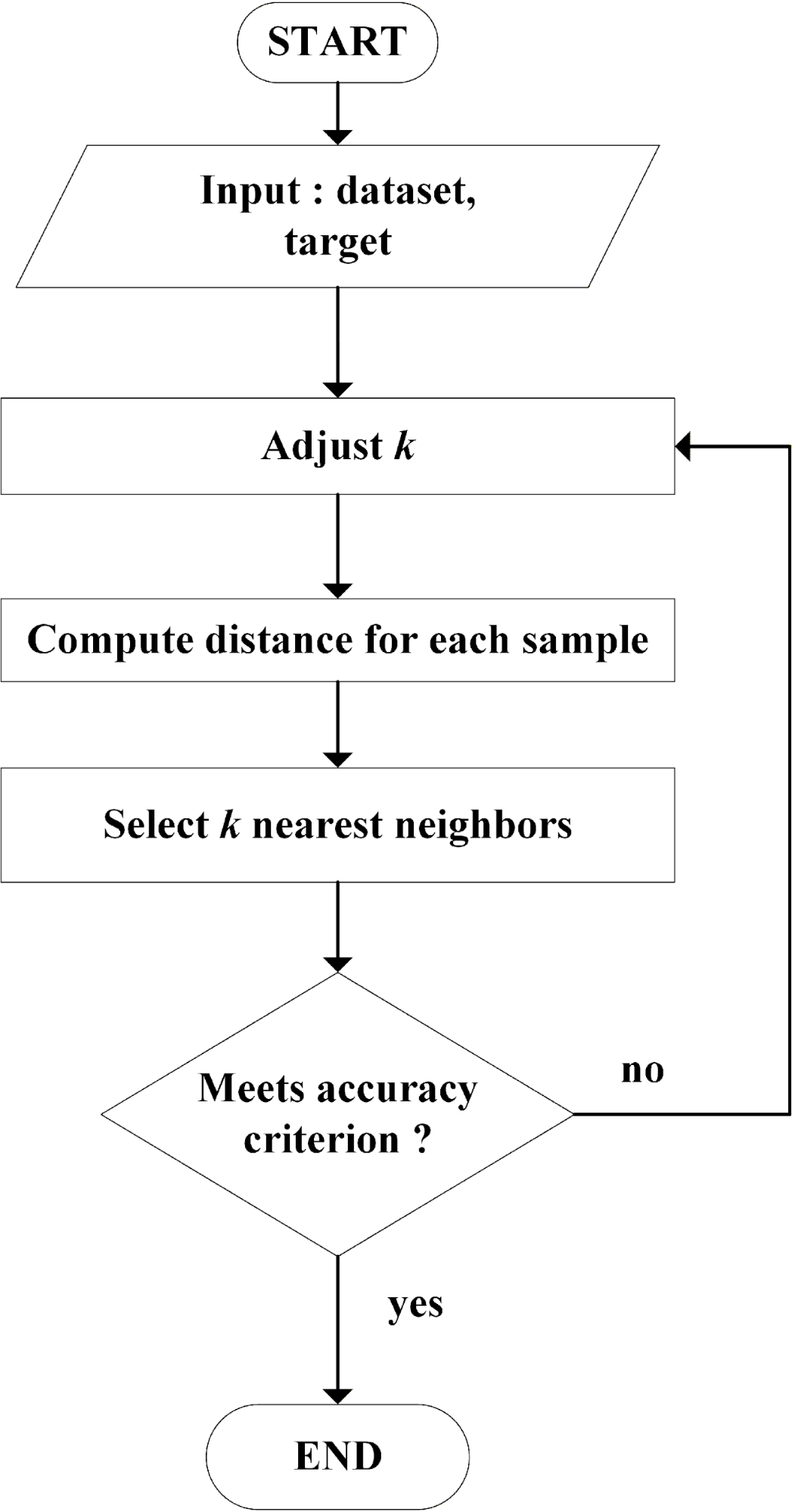

The K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) algorithm was employed to classify six categories of eye movement: right, left, up, down, voluntary blink, and involuntary blink. Each feature vector was compared with all labeled samples in the training dataset using the Euclidean distance metric, and the class label of each new observation was determined by majority voting among the k nearest neighbors. The value of k was empirically optimized to achieve a balance between classification accuracy and computational efficiency. The discrimination between voluntary and involuntary blinks was based on amplitude–duration feature analysis, where intentional blinks consistently exhibited higher peak amplitudes and longer durations. This separation was experimentally validated during feature extraction, confirming robust differentiation across all participants. The complete dataset, obtained from ten participants (aged 18–22) performing thirty repetitions for each movement, was divided into training (eight participants) and testing (two participants) subsets to evaluate cross-subject generalization. The training dataset was used to construct the classification model, while the testing dataset was applied for independent evaluation of recognition performance. The classification pipeline is summarized in Figure 7, which outlines feature processing, distance computation, nearest-neighbor selection, majority voting, and accuracy assessment across different k values. The corresponding classification accuracy and confusion matrix results are presented and discussed in the Results section.

Figure 7. Flowchart of the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) classification procedure

- Experimental Procedure

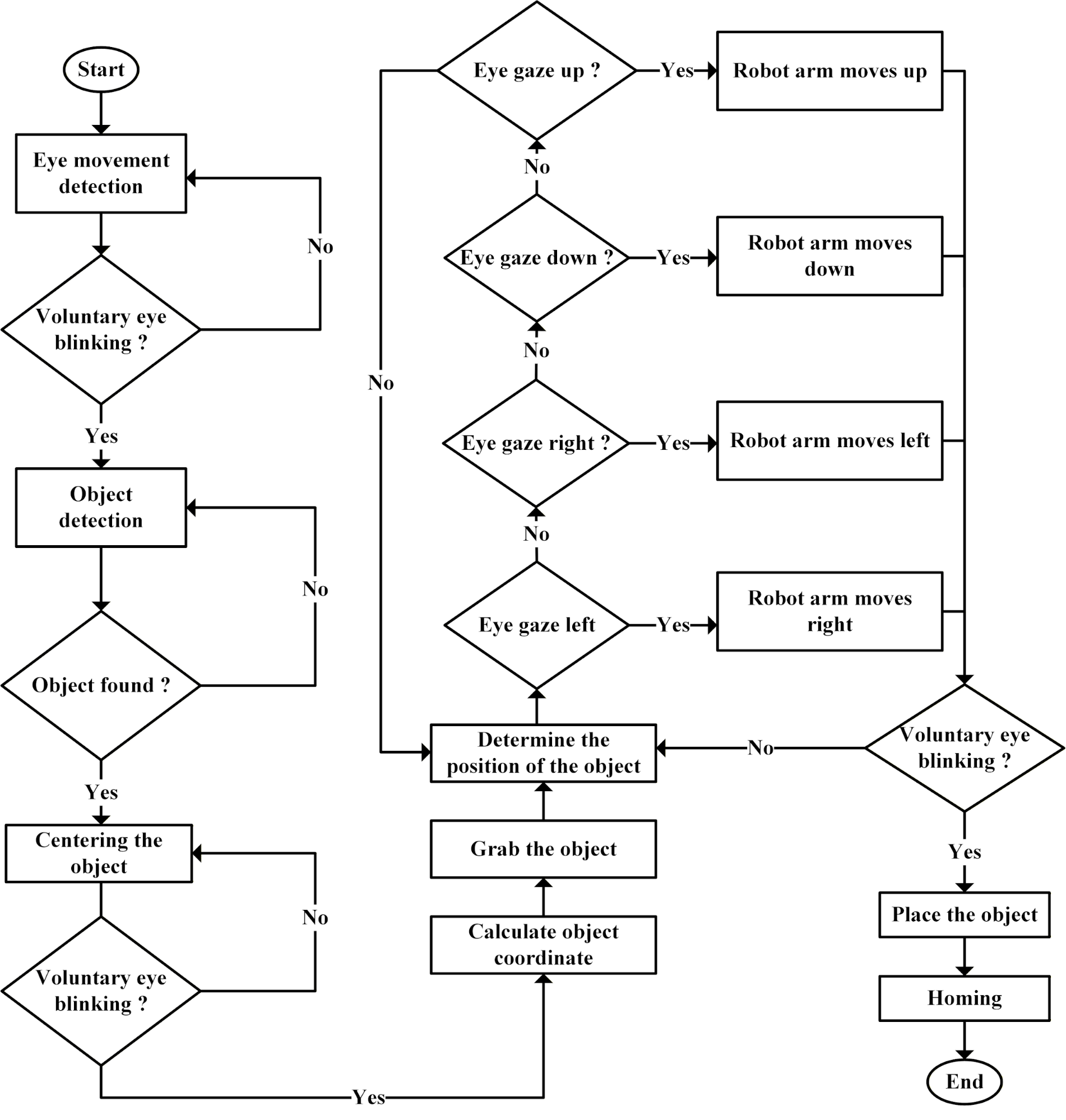

The experimental procedure was designed to evaluate the integrated performance of the proposed EOG–vision–based robotic control system under controlled laboratory conditions. The testing environment maintained a uniform illuminance level of approximately 500 lux using ceiling-mounted LED panels to minimize shadows and glare. This setup ensured stable performance for both EOG acquisition and vision-based object detection, replicating realistic indoor lighting conditions. The operational workflow of the complete system is illustrated in Figure 8. After initialization, the system continuously monitors the user’s eye activity through the EOG acquisition module. A voluntary blink serves as the activation command, triggering the vision subsystem to initiate a scanning process using the mounted camera. The live camera feed is displayed on the user interface, allowing the user to observe detected objects within the manipulator’s workspace. Object identification and coordinate extraction are performed in real time, and the detected object is subsequently targeted for grasping.

Upon successful object recognition, the inverse kinematics module determines the joint angles required to position the manipulator’s end effector. The manipulator then executes a trajectory toward the selected object. During this process, users can fine-tune the end-effector position through directional gaze commands (right, left, up, and down). Once the desired position is achieved, a second voluntary blink command is used to perform grasping and initiate object release, completing the manipulation cycle. To prevent unintended actions due to involuntary blinks or noise artifacts, a temporal refractory window of 300–500 ms was implemented after each command to reject overlapping signals and maintain control stability. System performance was evaluated through ten randomized object-retrieval trials conducted across ten predefined workspace coordinates. Each trial encompassed the full operational loop—object detection, positioning, grasping, and placement. Performance metrics, including success rate, positioning smoothness, and response latency, were recorded to assess the overall accuracy and stability of the control algorithm. These quantitative results are presented and analyzed in the Results and Discussion section.

Figure 8. Flowchart of the integrated EOG–vision–based robotic control system

- RESULT AND DISCUSSION

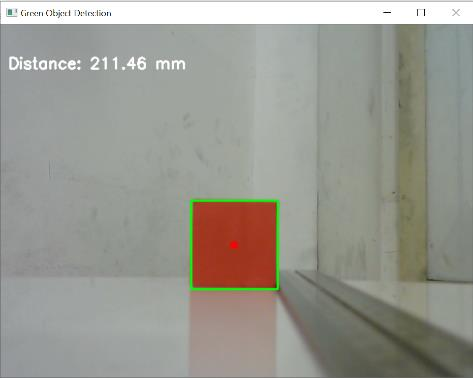

- Object Distance Estimation Analysis

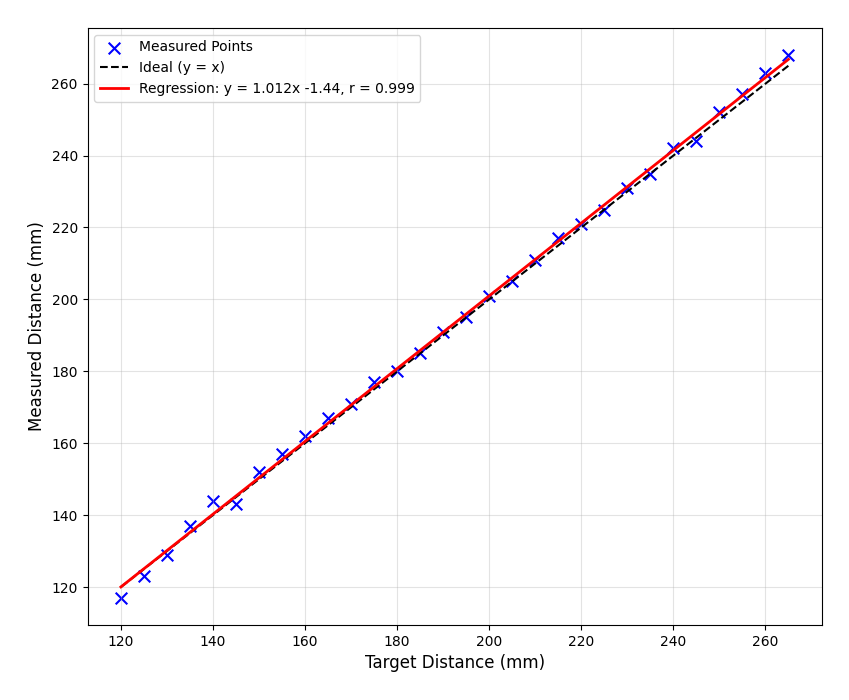

Analyses were conducted to evaluate the accuracy and consistency of the vision-based object distance estimation system integrated into the EOG–vision robotic control architecture. A total of 30 measurement points were obtained within a controlled laboratory environment, with target distances ranging from 120 mm to 265 mm. Each distance measurement was performed three times under identical lighting conditions (approximately 500 lux) to minimize random error and ensure repeatability. The Logitech C270 camera was fixed throughout all trials, maintaining constant focal length calibration and optical alignment to ensure consistent imaging geometry. The object—a red cube used for all experiments—was positioned sequentially at predefined distances, and its centroid coordinates were detected using the image-based distance estimation algorithm. This configuration allowed direct correlation between actual target distances and those estimated by the camera system. The comparison between target and measured distances exhibited a strong linear relationship, as illustrated in Figure 9. Regression analysis yielded a correlation coefficient of r = 0.999, indicating a near-perfect linearity between the measured and target values. The regression line followed the relationship 𝑦=1.012𝑥−1.44, confirming a minimal systematic bias in measurement. The resulting scatter distribution demonstrated that all measured data points closely aligned with the ideal reference line (y = x), suggesting the robustness of the system calibration and optical stability under the experimental setup.

Statistical evaluation of the results revealed a mean absolute error (MAE) of 1.5 mm with a standard deviation of 1.6 mm, reflecting high measurement precision within the designated working range. The maximum recorded error occurred at a distance of 140 mm (2.9%), attributed to slight nonlinearity in pixel-to-depth conversion and reduced calibration accuracy near the image periphery. Conversely, zero-error measurements were observed at multiple intermediate distances (180 mm, 185 mm, 195 mm, 205 mm, 225 mm, and 235 mm), verifying optimal accuracy in the camera’s central field of view. These findings confirm the reliability of the vision-based distance estimation algorithm in short- to mid-range operations, which are typical in assistive manipulation tasks. A paired-sample t-test was conducted to assess the statistical significance of deviation between the target and measured distances. The result indicated no statistically significant difference (p = 0.412, p > 0.05), demonstrating that the observed variations are within acceptable measurement uncertainty limits. The visual correlation between target and measured data points is presented in Figure 10, highlighting the strong linear relationship and minimal variance in depth estimation. These outcomes confirm that the system’s camera-based measurement framework is sufficiently accurate for use in the subsequent inverse kinematics computation and real-time positioning of the manipulator. Further calibration refinement and multi-object validation are recommended in future work to enhance robustness under non-ideal lighting and dynamic conditions.

Figure 9. Real-time image-based distance measurement output showing the detected object (red cube) within the defined region of interest (ROI) and corresponding distance display (211.46 mm)

Figure 10. Correlation between target and measured object distances across 30 test points

- Inverse Kinematic Performance Accuracy

The inverse kinematics (IK) performance evaluation was conducted to assess the spatial precision of the 4-DOF manipulator in executing object positioning tasks under two retrieval configurations: Scenario 1 (Frontal Retrieval) and Scenario 2 (Top-Down Retrieval). Each experiment involved ten randomized target points representing the manipulator’s reachable workspace limits. The experimental setups are illustrated in Figure 11(a) and Figure 11(b), which depict the physical configurations used for frontal and top-down retrieval, respectively. During testing, the end effector was commanded to reach predefined ( ) coordinates derived from the analytical trigonometric IK formulation described in the previous section. These evaluations aimed to verify the manipulator’s ability to reproduce precise end-effector positions in both planar and vertical orientations.

) coordinates derived from the analytical trigonometric IK formulation described in the previous section. These evaluations aimed to verify the manipulator’s ability to reproduce precise end-effector positions in both planar and vertical orientations.

|

|

(a) | (b) |

Figure 11. Experimental setup for inverse-kinematics evaluation: (a) Frontal retrieval configuration; (b) Top-down retrieval configuration

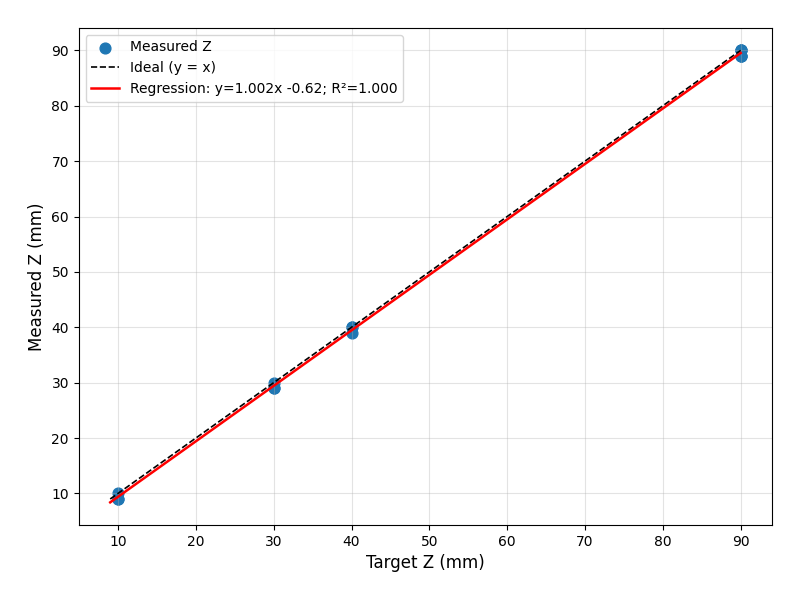

The mean absolute error (MAE) was computed as the average of absolute deviations across the X, Y, and Z axes, while Average Accuracy represents the percentage agreement between commanded and measured coordinates relative to the workspace span. In Scenario 1 (Frontal Retrieval), the manipulator achieved a MAE of 0.64 mm and an average positional accuracy of 99.45%, indicating excellent alignment between theoretical and experimental coordinates. The minimal deviation observed can be attributed to servo backlash, rounding errors in inverse-trigonometric computation, and minor encoder quantization effects. In Scenario 2 (Top-Down Retrieval), the manipulator achieved a MAE of 1.58 mm and average accuracy of 99.31%. Although slightly lower, this performance remains within acceptable tolerances and reflects increased mechanical loading and gravitational effects on the vertical-axis joints. A descriptive comparison between the two scenarios indicated that the variation in positioning accuracy was minor and within expected tolerance limits.

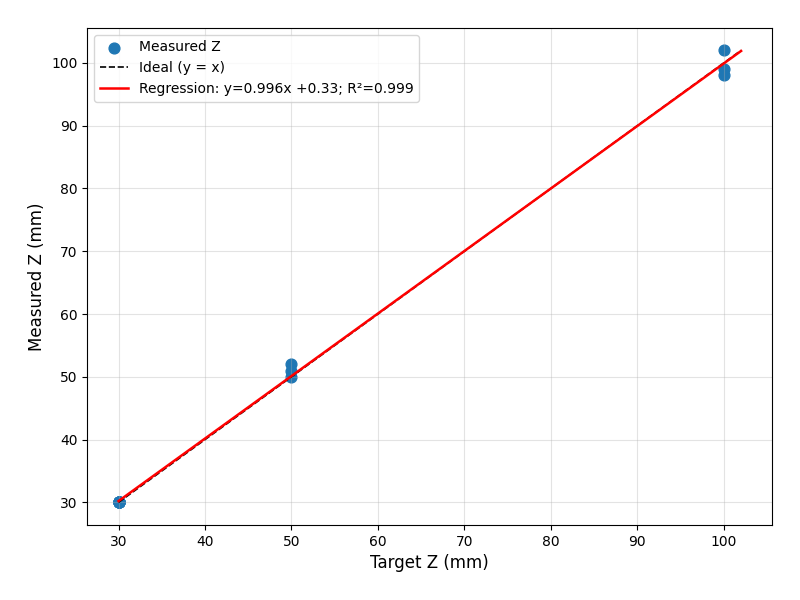

To provide visual insight into the spatial correspondence between commanded and measured positions, Figure 12(a) and Figure 12(b) present scatter plots for the frontal and top-down retrieval configurations, respectively. Both plots exhibit a strong linear correlation ( = 1.000 and 0.999) between target and measured coordinates, confirming the high fidelity of the implemented kinematic model. The close clustering of points along the diagonal identity line demonstrates that the end effector accurately follows intended trajectories, with only slight deviations near the workspace boundaries. These minor discrepancies are likely caused by nonlinear servo torque characteristics and small projection errors when operating near kinematic limits.

= 1.000 and 0.999) between target and measured coordinates, confirming the high fidelity of the implemented kinematic model. The close clustering of points along the diagonal identity line demonstrates that the end effector accurately follows intended trajectories, with only slight deviations near the workspace boundaries. These minor discrepancies are likely caused by nonlinear servo torque characteristics and small projection errors when operating near kinematic limits.

As depicted in Figure 11(a), the frontal retrieval configuration demonstrates the manipulator’s capability to extend horizontally with smooth lateral control and minimal vertical offset. In contrast, Figure 11(b) illustrates the top-down retrieval configuration, where the manipulator performs vertical descent toward the object, introducing higher torque demands and requiring tighter joint synchronization. Collectively, the photographic and analytical evidence confirms that the developed inverse kinematics formulation is robust across orientations, offering consistent, repeatable sub-millimeter positioning accuracy suitable for assistive-robotic applications. These findings also establish a quantitative basis for the subsequent system-integration tests, in which EOG-based control commands are applied to the same manipulator under identical workspace constraints.

|

(a) |

|

(b) |

Figure 12. Scatter plots of target versus measured coordinates: (a) Frontal retrieval; (b) Top-down retrieval

- Effectiveness of KNN in EOG Signal Classification

The K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) algorithm was applied to classify six eye movement categories: right, left, up, down, voluntary blink, and involuntary blink. The recorded EOG signals were preprocessed through differential amplification and bandpass filtering (0–10 Hz), then digitized at 250 Hz using the NI USB-6009 interface. Data from ten healthy participants were used, divided in an 8:2 ratio for training and testing sets. Each movement was repeated thirty times per participant, producing a balanced dataset for supervised learning. The extracted features included amplitude ( ) and duration (

) and duration ( ), which represent signal intensity and temporal length of each ocular movement. Table 1 lists the average

), which represent signal intensity and temporal length of each ocular movement. Table 1 lists the average  and Td for all movements. Horizontal gazes generated clear bipolar responses between channels, while vertical movements showed smaller amplitude differences. Blinks produced the largest

and Td for all movements. Horizontal gazes generated clear bipolar responses between channels, while vertical movements showed smaller amplitude differences. Blinks produced the largest  values, with voluntary blinks lasting longer than involuntary ones—confirming that amplitude–duration features effectively distinguish intentional from reflexive responses.

values, with voluntary blinks lasting longer than involuntary ones—confirming that amplitude–duration features effectively distinguish intentional from reflexive responses.

The influence of the  value on recognition performance was analyzed, as summarized in Table 2. The highest classification accuracy was achieved when

value on recognition performance was analyzed, as summarized in Table 2. The highest classification accuracy was achieved when  = 3, providing the best balance between bias and variance. Smaller K values caused sensitivity to noise, while larger values led to over-smoothing of decision boundaries. This optimization ensured consistent classification while maintaining low computational cost, which is crucial for real-time robotic integration. The final evaluation results are presented in Table 3, showing an overall classification accuracy of 98.17%, with a True Positive Rate (TPR) of 98.47% and a False Negative Rate (FNR) of 1.53%. The confusion matrix indicates that the most frequent misclassification occurred between upward gaze and voluntary blink, with 11 samples confused. This error likely arises from similar transient waveforms caused by eyelid motion when subjects look upward. Despite this overlap, recognition of horizontal and downward movements remained highly consistent, confirming the stability of the feature extraction process.

= 3, providing the best balance between bias and variance. Smaller K values caused sensitivity to noise, while larger values led to over-smoothing of decision boundaries. This optimization ensured consistent classification while maintaining low computational cost, which is crucial for real-time robotic integration. The final evaluation results are presented in Table 3, showing an overall classification accuracy of 98.17%, with a True Positive Rate (TPR) of 98.47% and a False Negative Rate (FNR) of 1.53%. The confusion matrix indicates that the most frequent misclassification occurred between upward gaze and voluntary blink, with 11 samples confused. This error likely arises from similar transient waveforms caused by eyelid motion when subjects look upward. Despite this overlap, recognition of horizontal and downward movements remained highly consistent, confirming the stability of the feature extraction process.

Compared to previous EOG-based systems—such as those by [85] and [86], which achieved accuracies between 92–96%—the proposed method demonstrates superior reliability under controlled laboratory conditions. The improvement may result from the use of dual-channel input and well-tuned preprocessing stages. Nonetheless, the dataset remains limited to ten participants under stable lighting, so future validation in dynamic or noisy environments is recommended. Overall, these findings confirm that amplitude–duration analysis combined with KNN provides a robust framework for distinguishing voluntary from involuntary eye movements. This classification outcome forms the foundation for integrating EOG-based commands with robotic manipulation, as discussed in the following section.

Table 1. Eye movement signal extraction feature

Label | Eye movement | Signal Feature |

Amplitude ( ) ) | Duration ( ) ) |

Ch 1 | Ch 2 | Ch 1 | Ch 2 |

1 | Right | 0.82 V | -1.23 V | 4 ms | 6 ms |

2 | Left | -1.17 V | 1.28 V | 7 ms | 6 ms |

3 | Up | -2.08 V | -1.40 V | 10 ms | 8 ms |

4 | Down | 2.03 V | 1.74 V | 8 ms | 8 ms |

5 | Voluntary blink | -2.34 V | -1.56 V | 8 ms | 7 ms |

6 | Involuntary blinking | -1.37 V | -0.94 V | 3 ms | 3 ms |

Table 2.  -Value variations and their corresponding accuracy rates

-Value variations and their corresponding accuracy rates

Value Value

| Accuracy |

3 | 94.79% |

5 | 94.38% |

7 | 98.17% |

9 | 92.92% |

11 | 93.12% |

Table 3. Confusion matrix KNN Classification

Target | Prediction | TPR | FNR | PRECISION |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

1 | 120 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 % | 0 % | 100 % |

2 | 0 | 120 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 % | 0 % | 100 % |

3 | 0 | 0 | 109 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 90,83 % | 9,20 % | 100 % |

4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 120 | 0 | 0 | 100 % | 0 % | 100 % |

5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 0 | 100 % | 0 % | 84,51 % |

6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 100 % | 0 % | 100 % |

Accuracy | 98,17% |

- Assessment of Control Capabilities in Robot Manipulator

The integrated EOG–vision–manipulator control system was experimentally implemented to evaluate its operational reliability and responsiveness under real-time closed-loop conditions. The evaluation procedure followed the automated workflow illustrated in Figure 8, beginning with user eye-activity monitoring and object localization, and concluding with the successful transfer of the object to a designated location. Each cycle of operation consisted of the user intentionally performing an eye-blink command to initiate scanning, visual confirmation of the detected object through the camera interface, and subsequent robotic retrieval and placement. All experiments were conducted in a controlled indoor environment under uniform illumination (≈ 500 lux) to minimize the effects of lighting variability on both EOG and vision subsystems.

System performance was assessed by commanding the manipulator to retrieve and place objects at ten randomized target points within its reachable workspace. Each operation was evaluated based on trajectory smoothness, task completion time, and operational success rate. To ensure objectivity, smoothness was defined quantitatively using temporal and kinematic thresholds derived from the mechanical characteristics of the servomotors. Each servo provides a positional resolution of 0.29° per step, corresponding to approximately 0.5 mm of linear displacement for a 100 mm link. Consequently, trajectory deviations within 2 mm correspond to encoder errors below four steps (Smooth), deviations between 2–4 mm represent moderate synchronization delays (Fairly Smooth), and deviations exceeding 4 mm indicate accumulated mechanical play or latency (Less Smooth). These spatial thresholds were cross-validated with empirical completion times—Smooth < 5 s, Fairly Smooth = 5–7 s, and Less Smooth > 7 s—derived from the average joint velocity of 354°/s and control-loop latency. This servo-based calibration ensures that the smoothness metric accurately represents measurable system performance rather than subjective observation.

The experimental results, summarized in Table 4, show an overall success rate of 99.48% for frontal retrieval and 97.96% for top-down retrieval configurations. Frontal retrieval consistently exhibited smoother motion trajectories and shorter completion times, reflecting lower gravitational loading and reduced synchronization demand across the manipulator joints. In contrast, top-down retrieval presented slightly higher trajectory deviation due to vertical torque compensation and joint backlash when operating near the upper workspace limit. Nonetheless, all operations remained within sub-millimeter precision and below the acceptable 2 mm threshold, confirming stable end-effector control and high mechanical repeatability. Statistical comparison of the trajectory deviations revealed no significant difference between the two configurations (p > 0.05), validating the reliability of the proposed kinematic and control model.

The comprehensive evaluation confirms that the developed EOG-driven robotic system can perform coordinated eye-controlled manipulation with high positional accuracy and repeatability. Minor deviations observed under vertical actuation conditions suggest areas for future improvement, including adaptive torque compensation, dynamic recalibration under varying loads, and incorporation of real-time fatigue adaptation algorithms. While current results were obtained under ideal laboratory conditions, future validation in unstructured environments—with dynamic lighting and user variability—is expected to enhance robustness and clinical applicability. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that the proposed control framework achieves a consistent balance between responsiveness, precision, and usability, establishing a robust foundation for next-generation assistive robotic systems designed for individuals with severe motor impairments.

Table 4. Quantitative Evaluation of System Performance Under Frontal and Top-Down Retrieval Scenarios

Trial No. | Scenario | Target Point | Completion Time (s) | Trajectory Deviation (mm) | Smoothness Category | Success (%) |

1 – 5 | Frontal Retrieval | Random (1 – 5) | 3.8 – 4.7 | 1.1 – 1.9 | Smooth | 99.48 |

6 – 10 | Top-Down Retrieval | Random (6 – 10) | 5.4 – 6.9 | 2.5 – 3.8 | Fairly Smooth | 97.96 |

- Discussions

The experimental outcomes demonstrate that the proposed EOG–vision–based control framework achieves reliable performance in real-time robotic manipulation. The KNN classifier obtained a mean accuracy of 98.17%, outperforming conventional EOG-based control systems reported by [85] and [86], which ranged from 92–96%. This improvement is primarily attributed to the dual-channel signal acquisition, optimized bandpass filtering (0–10 Hz), and amplitude–duration feature extraction that effectively separate voluntary and involuntary blinks. Despite the high classification rate, misclassification between upward gaze and voluntary blink (9.2%) indicates partial overlap in waveform morphology due to eyelid artifacts, suggesting that adaptive thresholding or temporal gating could further enhance reliability.

The inverse kinematics (IK) evaluation confirms the analytical model’s precision, achieving sub-millimeter mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.64 mm in frontal retrieval and 1.58 mm in top-down retrieval configurations. This result demonstrates a >99% positional accuracy, which is superior to previously reported low-cost EOG-controlled manipulators that typically operate within 3–5 mm tolerance. The minor deviation between the two configurations reflects mechanical backlash and gravitational effects in vertical motion but remains within acceptable tolerance for assistive applications. These findings validate that the 4-DOF manipulator design provides an optimal trade-off between dexterity and computational efficiency, supporting real-time responsiveness without kinematic redundancy.

Integration of vision-based distance measurement improved spatial awareness by providing reliable object localization, with a mean absolute error of 1.5 ± 1.6 mm and correlation coefficient r = 0.999. The pinhole camera model calibration successfully minimized optical distortion, yielding accurate mapping between real-world and image coordinates. Compared to manual depth estimation or single-camera monocular systems, this result indicates a 2–3× improvement in measurement precision, enabling consistent grasping alignment and smooth end-effector trajectories.

At the system level, overall manipulation success rates reached 99.48% (frontal) and 97.96% (top-down). This confirms that the hybrid EOG–vision–IK approach ensures stable control and task completion even under varying approach angles. The observed completion time difference (3.8–4.7 s vs. 5.4–6.9 s) is consistent with servo torque and load variations. Notably, all trajectories were categorized as “Smooth” or “Fairly Smooth,” corresponding to mechanical deviations below 4 mm, reinforcing that the servos can deliver repeatable precision at moderate speed when synchronized via analytical IK.

From an application standpoint, these results establish the feasibility of intuitive EOG-based assistive manipulation for users with preserved ocular control but limited limb mobility. The system’s robustness under controlled laboratory illumination (≈500 lux) suggests potential adaptability to clinical or rehabilitation settings, where consistent lighting can be maintained. However, further validation is needed under dynamic lighting and user-fatigue conditions to assess signal drift, calibration longevity, and cognitive load. The combination of high classification accuracy, sub-millimeter positioning, and near-perfect task success rate demonstrates a significant advancement over previous EOG-only control paradigms, offering a foundation for next-generation assistive robotic interfaces.

- CONCLUSIONS

This paper presented a multimodal control framework integrating Electrooculography (EOG) signals with camera-based visual feedback for intuitive and precise robotic manipulator control. The proposed system achieved 98.17% classification accuracy and sub-millimeter end-effector precision (0.7–1.58 mm MAE), outperforming conventional EOG-based methods that typically achieve 85–92% accuracy. The integration of vision-based spatial mapping (1.5 ± 1.6 mm error), inverse kinematic computation, and EOG signal interpretation (TPR: 98.47%, FNR: 1.53%) established a synergistic multimodal control mechanism, in which complementary sensing modalities provided precision and reliability beyond those of single-modality systems.

From a theoretical standpoint, this work advances the concept of bio-signal-driven multimodal fusion in assistive robotics. The findings indicate that systematic fusion of EOG and visual information yields superior performance compared to independent modalities, that a 4-DOF manipulator configuration represents an optimal balance between kinematic reach and computational tractability for real-time control, and that a hybrid automation scheme combining autonomous perception with user-intent-driven actuation can reduce cognitive load while preserving user agency. These contributions collectively provide a foundation for adaptive and user-centered robotic systems that bridge neural intent and precise motor execution.

Experimental evaluation was performed under controlled laboratory conditions (500 lux illumination, n = 10 healthy participants, aged 18–22, standardized object set). The training dataset (n = 10, 8:2 train–test partition) and limited trial duration (<30 min) constrain the assessment of long-term adaptability and inter-subject variability. Consequently, additional validation across diverse clinical populations (e.g., ALS and high-level SCI), illumination conditions (200–1000 lux), and extended operation (>2 h) is required prior to clinical translation. System limitations were identified in four primary domains: illumination sensitivity (maximum 2.9% error), signal degradation from ocular fatigue, user-specific calibration dependency, and computational latency from concurrent processing. Addressing these constraints will necessitate the implementation of adaptive illumination compensation, fatigue-resilient feature extraction, transfer-learning-based calibration, and hardware acceleration achieving sub-50 ms response latency.

Future research will emphasize clinical-scale validation in uncontrolled environments, incorporating longitudinal evaluations of accuracy, stability, and user adaptation over extended sessions (2–4 h). Although quantitative fatigue data were not collected in this study, prior EOG-based control research has reported measurable performance degradation during prolonged operation, underscoring the importance of fatigue-adaptive recalibration mechanisms. The development of adaptive learning algorithms for online calibration, fatigue detection, and transfer learning is anticipated to enhance system robustness and usability. Furthermore, integrating multimodal feedback and performing comparative assessments with alternative control paradigms such as EMG, BCI, and SSVEP will provide quantitative benchmarks for performance, user preference, and long-term operability. Establishing validated performance baselines under both controlled and semi-natural conditions defines a concrete trajectory toward clinical translation. Ultimately, the integration of adaptive intelligence, optimized embedded architectures, and systematic clinical validation is expected to advance next-generation assistive robotic systems that restore functional autonomy for individuals with severe motor impairments.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology of Indonesia with Letter of Decree 0667/E5/AL04/2024 and Contract Number: 041/E5/PG.02.00.PL/2024 in June

11th, 2024.

REFERENCES

- A. Ghaffar, A. A. Dehghani-Sanij, and S. Q. Xie, “Actuation system modelling and design optimization for an assistive exoskeleton for disabled and elderly with series and parallel elasticity,” THC, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 1129–1151, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3233/THC-220145.

- A. G and R. S, “A Novel Approach to Elderly Care Robotics Enhanced With Leveraging Gesture Recognition and Voice Assistance,” in 2024 Asia Pacific Conference on Innovation in Technology (APCIT), pp. 1–6, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/APCIT62007.2024.10673657.

- C. L. Kok, C. K. Ho, T. H. Teo, K. Kato, and Y. Y. Koh, “A Novel Implementation of a Social Robot for Sustainable Human Engagement in Homecare Services for Ageing Populations,” Sensors, vol. 24, no. 14, p. 4466, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/s24144466.

- G. Arunachalam, P. M. R, M. N. Varadarajan, V. L. Vinya, T. Geetha, and S. Murugan, “Human-Robot Interaction in Geriatric Care: RNN Model for Intelligent Companionship and Adaptive Assistance,” in 2024 2nd International Conference on Sustainable Computing and Smart Systems (ICSCSS), pp. 1067–1073, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSCSS60660.2024.10624951.

- F. Liang, Z. Su, and W. Sheng, “Multimodal Monitoring of Activities of Daily Living for Elderly Care,” IEEE Sensors J., vol. 24, no. 7, pp. 11459–11471, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2024.3366188.

- W. Wang, W. Ren, M. Li, and P. Chu, “A Survey on the Use of Intelligent Physical Service Robots for Elderly or Disabled Bedridden People at Home,” Int. J. Crowd Sci., vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 88–94, 2024, https://doi.org/10.26599/IJCS.2024.9100005.

- A. A. Alshdadi, “Evaluation of IoT-Based Smart Home Assistance for Elderly People Using Robot,” Electronics, vol. 12, no. 12, p. 2627, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12122627.

- S. J, K. M, S. M, and L. S, “Design and Development of Fully Functional Prosthesis Robotic ARM,” in 2023 Eighth International Conference on Science Technology Engineering and Mathematics (ICONSTEM), pp. 1–5, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICONSTEM56934.2023.10142370.

- F. F. Parsa, A. A. A. Moghadam, D. Stollberg, A. Tekes, C. Coates, and T. Ashuri, “A Novel Soft Robotic Hand for Prosthetic Applications,” in 2022 IEEE 19th International Conference on Smart Communities: Improving Quality of Life Using ICT, IoT and AI (HONET), pp. 1–6, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/HONET56683.2022.10019175.

- M. S. Han and C. K. Harnett, “Journey from human hands to robot hands: biological inspiration of anthropomorphic robotic manipulators,” Bioinspir. Biomim., vol. 19, no. 2, p. 021001, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-3190/ad262c.

- F. Khadivar, V. Mendez, C. Correia, I. Batzianoulis, A. Billard, and S. Micera, “EMG-driven shared human-robot compliant control for in-hand object manipulation in hand prostheses,” J. Neural Eng., vol. 19, no. 6, p. 066024, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/aca35f.

- D. Ubosi, “Robotic prosthetic hands - A review,” TechRxiv, 2023, https://doi.org/10.36227/techrxiv.24103386.v1.

- L. D. F. G. Bittencourt and M. A. Fraga, “Initial Development of a Low-Cost Assistive Robotic Manipulator Using ESP32,” in 2024 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Systems and Emergent Technologies (IC_ASET), pp. 1–6, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/IC_ASET61847.2024.10596218.

- K. Moulaei, K. Bahaadinbeigy, A. A. Haghdoostd, M. S. Nezhad, and A. Sheikhtaheri, “Overview of the role of robots in upper limb disabilities rehabilitation: a scoping review,” Arch Public Health, vol. 81, no. 1, p. 84, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-023-01100-8.

- Z. Jiryaei and A. S. Jafarpisheh, “The usefulness of assistive soft robotics in the rehabilitation of patients with hand impairment: A systematic review,” Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, vol. 39, pp. 398–409, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2024.02.025.

- N.-K. Nguyen, T.-M.-P. Dao, T.-D. Nguyen, D.-T. Nguyen, H.-T. Nguyen, and V.-K. Nguyen, “An sEMG Signal-based Robotic Arm for Rehabilitation applying Fuzzy Logic,” Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res., vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 14287–14294, 2024, https://doi.org/10.48084/etasr.7146.

- D. Huamanchahua, L. A. Huaman-Levano, J. Asencios-Chavez, and N. Caballero-Canchanya, “Biological Signals for the Control of Robotic Devices in Rehabilitation: An Innovative Review,” in 2022 IEEE International IOT, Electronics and Mechatronics Conference (IEMTRONICS), pp. 1–7, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/IEMTRONICS55184.2022.9795719.

- M. Ayachi and H. Seddik, “Overview of EMG Signal Preprocessing and Classification for Bionic Hand Control,” in 2022 IEEE Information Technologies & Smart Industrial Systems (ITSIS), pp. 1–6, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/ITSIS56166.2022.10118387.

- D. Patil, M. Nathwani, S. Nemane, M. Patil, and S. Sondkar, “Wireless Control of 4 D.O.F. Robotic Arm using EMG Muscle Sensors.,” in 2024 IEEE 5th India Council International Subsections Conference (INDISCON), pp. 1–6, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/INDISCON62179.2024.10744320.

- F. Ferrari, E. Zimei, M. Gandolla, A. Pedrocchi, and E. Ambrosini, “An EMG-triggered cooperative controller for a hybrid FES-robotic system,” in 2023 IEEE International Conference on Metrology for eXtended Reality, Artificial Intelligence and Neural Engineering (MetroXRAINE), pp. 852–857, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/MetroXRAINE58569.2023.10405687.

- H. Riyadh Mahmood, M. K. Hussein, and R. A. Abedraba, “Development of Low-Cost Biosignal Acquisition System for ECG, EMG, and EOG,” ejuow, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 191–202, 2022, https://doi.org/10.31185/ejuow.Vol10.Iss3.352.

- H. Aly and S. M. Youssef, “Bio-signal based motion control system using deep learning models: a deep learning approach for motion classification using EEG and EMG signal fusion,” J Ambient Intell Human Comput, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 991–1002, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12652-021-03351-1.

- R. Fu, Q. Li, S. Wang, and G. Sun, “Teleoperation Method For Controlling Robotic Arm Based On Multi-channel EMG Signals,” in 2023 38th Youth Academic Annual Conference of Chinese Association of Automation (YAC), pp. 1264–1268, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/YAC59482.2023.10401439.

- V. Prakash and K. G, “Comprehensive Analysis of an EMG Based Human-Robot Interface Using Various Machine Learning Techniques,” Philipp J Sci, vol. 152, no. 6B, 2024, https://doi.org/10.56899/152.6B.12.

- B. Chen et al., “A Real-Time EMG-Based Fixed-Bandwidth Frequency-Domain Embedded System for Robotic Hand,” Front. Neurorobot., vol. 16, p. 880073, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbot.2022.880073.

- C. L. Kok, C. K. Ho, F. K. Tan, and Y. Y. Koh, “Machine Learning-Based Feature Extraction and Classification of EMG Signals for Intuitive Prosthetic Control,” Applied Sciences, vol. 14, no. 13, p. 5784, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/app14135784.

- B. Murali and R. F. Ff. Weir, “Towards a Minimal-Delay Myoelectric Control Signal Using Thresholded Surface EMG,” in 2024 10th IEEE RAS/EMBS International Conference for Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics (BioRob), pp. 675–680, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/BioRob60516.2024.10719734.

- J. Arnold et al., “Personalized ML-based wearable robot control improves impaired arm function,” Nat Commun, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 7091, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62538-8.

- J. A. Joby, P. Sikorski, T. Sultan, H. Akbarpour, F. Esposito, and M. Babaiasl, “EMG-TransNN-MHA: A Transformer-Based Model for Enhanced Motor Intent Recognition in Assistive Robotics,” in 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), pp. 8691–8693, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/BigData62323.2024.10825417.

- J. Yang, K. Shibata, D. Weber, and Z. Erickson, “High-density electromyography for effective gesture-based control of physically assistive mobile manipulators,” npj Robot, vol. 3, no. 1, p. 2, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1038/s44182-025-00018-3.

- N. Barbara, T. A. Camilleri, and K. P. Camilleri, “Real-time continuous EOG-based gaze angle estimation with baseline drift compensation under stationary head conditions,” Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, vol. 86, p. 105282, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2023.105282.

- N. Barbara, T. A. Camilleri, and K. P. Camilleri, “A comparison of EOG baseline drift mitigation techniques,” Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, vol. 57, p. 101738, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2019.101738.

- K. Nguyen Trong et al., “Real-time Single-Channel EOG removal based on Empirical Mode Decomposition,” EAI Endorsed Trans Ind Net Intel Syst, vol. 11, no. 2, p. e5, Apr. 2024, https://doi.org/10.4108/eetinis.v11i2.4593.

- [34] N. Tulyakova and O. Trofymchuk, “Adaptive myriad filtering algorithms for removal of nonstationary noise in electrooculograms,” PC&I, vol. 68, no. 3, pp. 127–145, 2023, https://doi.org/10.34229/1028-0979-2023-3-12.

- C.-L. Teng, Y.-Y. Zhang, W. Wang, Y.-Y. Luo, G. Wang, and J. Xu, “A Novel Method Based on Combination of Independent Component Analysis and Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition for Removing Electrooculogram Artifacts From Multichannel Electroencephalogram Signals,” Front. Neurosci., vol. 15, p. 729403, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2021.729403.

- N. Gudikandula, R. Janapati, R. Sengupta, and S. Chintala, “Recent Advancements in Online Ocular Artifacts Removal in EEG based BCI: A Review,” in 2024 15th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), pp. 1–6, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCCNT61001.2024.10724228.

- C. O’Reilly and S. Huberty, “Removing EOG Artifacts from EEG Recordings using Deep Learning,” Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Advances in Signal Processing and Artificial Intelligence, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.24.595839.

- N. Schärer, F. Villani, A. Melatur, S. Peter, T. Polonelli, and M. Magno, “ElectraSight: Smart Glasses with Fully Onboard Non-Invasive Eye Tracking Using Hybrid Contact and Contactless EOG,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.14848, 2024, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2412.14848.

- S. Frey et al., "GAPses: Versatile Smart Glasses for Comfortable and Fully-Dry Acquisition and Parallel Ultra-Low-Power Processing of EEG and EOG," in IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Circuits and Systems, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 616-628, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1109/TBCAS.2024.3478798.

- A. H. R. da Costa and K. R. O’Keeffe, “Development of a Digital Front-End for Electrooculography Circuits to Facilitate Digital Communication in Individuals with Communicative and Motor Disabilities,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.03013, 2024, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2410.03013.

- D. Das, M. H. Chowdhury, A. Chowdhury, K. Hasan, Q. D. Hossain, and R. C. C. Cheung, “Application Specific Reconfigurable Processor for Eyeblink Detection from Dual-Channel EOG Signal,” JLPEA, vol. 13, no. 4, p. 61, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/jlpea13040061.

- X. Mai, X. Sheng, X. Shu, Y. Ding, X. Zhu, and J. Meng, “A Calibration-Free Hybrid Approach Combining SSVEP and EOG for Continuous Control,” IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng., vol. 31, pp. 3480–3491, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2023.3307814.

- S. Ban et al., “Soft Wireless Headband Bioelectronics and Electrooculography for Persistent Human–Machine Interfaces,” ACS Appl. Electron. Mater., vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 877–886, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaelm.2c01436.

- G. R. Müller-Putz et al., “Feel Your Reach: An EEG-Based Framework to Continuously Detect Goal-Directed Movements and Error Processing to Gate Kinesthetic Feedback Informed Artificial Arm Control,” Front. Hum. Neurosci., vol. 16, p. 841312, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2022.841312.

- M. Zibandehpoor, F. Alizadehziri, A. A. Larki, S. Teymouri, and M. Delrobaei, “Electrooculography Dataset for Objective Spatial Navigation Assessment in Healthy Participants,” 2024, arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2411.06811.

- Ç. Demirel, L. Reguş, and H. Köse, “Harmonic enhancement to optimize EOG based ocular activity decoding: A hybrid approach with harmonic source separation and EEMD,” Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 15, p. e35242, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e35242.

- C. Belkhiria and V. Peysakhovich, “Electro-Encephalography and Electro-Oculography in Aeronautics: A Review Over the Last Decade (2010–2020),” Front. Neuroergonomics, vol. 1, p. 606719, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnrgo.2020.606719.

- C. Belkhiria, A. Boudir, C. Hurter, and V. Peysakhovich, “EOG-Based Human–Computer Interface: 2000–2020 Review,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 13, p. 4914, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/s22134914.

- H. Danaci, L. A. Nguyen, T. L. Harman, and M. Pagan, “Inverse Kinematics for Serial Robot Manipulators by Particle Swarm Optimization and POSIX Threads Implementation,” Applied Sciences, vol. 13, no. 7, p. 4515, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/app13074515.

- Y. Zong, J. Huang, J. Bao, Y. Cen, and D. Sun, “Inverse kinematics solution of demolition manipulator based on global mapping,” Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science, vol. 238, no. 5, pp. 1561–1572, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1177/09544062231184791.

- A. U. Darajat, U. Murdika, A. S. Repelianto, and R. Annisa, “Inverse Kinematic of 1-DOF Robot Manipulator Using Sparse Identification of Nonlinear System,” Intek, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 22, 2023, https://doi.org/10.31963/intek.v10i1.4202.

- M. Li, X. Luo, and L. Qiao, “Inverse Kinematics of Robot Manipulator Based on BODE-CS Algorithm,” Machines, vol. 11, no. 6, p. 648, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/machines11060648.

- D. Patkó and A. Zelei, “Velocity and acceleration level inverse kinematic calculation alternatives for redundant manipulators,” Meccanica, vol. 56, no. 4, pp. 887–900, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11012-020-01305-z.

- M. Haohao et al., “Inverse kinematics of six degrees of freedom robot manipulator based on improved dung beetle optimizer algorithm,” IJRA, vol. 13, no. 3, p. 272, 2024, https://doi.org/10.11591/ijra.v13i3.pp272-282.

- A. Yonezawa, H. Yonezawa, and I. Kajiwara, “Simple Inverse Kinematics Computation Considering Joint Motion Efficiency,” IEEE Trans. Cybern., vol. 54, no. 9, pp. 4903–4914, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/TCYB.2024.3372989.

- M. T. Shahria, J. Ghommam, R. Fareh, and M. H. Rahman, “Vision-Based Object Manipulation for Activities of Daily Living Assistance Using Assistive Robot,” Automation, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 68–89, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/automation5020006.

- A. Ghorbanpour, “Cooperative Robot Manipulators Dynamical Modeling and Control: An Overview,” Dynamics, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 820–854, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/dynamics3040045.

- S. Benameur, S. Tadrist, M. A. Mellal, and E. J. Williams, “Basic Concepts of Manipulator Robot Control:,” in Advances in Computational Intelligence and Robotics, pp. 1–12, 2022, https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-5381-0.ch001.

- A. A. Ayazbai, G. Balbaev, and S. Orazalieva, “Manipulator Control Systems Review,” Вестник КазАТК, vol. 124, no. 1, pp. 245–253, 2023, https://doi.org/10.52167/1609-1817-2023-124-1-245-253.

- A. Nanavati, V. Ranganeni, and M. Cakmak, “Physically Assistive Robots: A Systematic Review of Mobile and Manipulator Robots That Physically Assist People with Disabilities,” Annual Review of Control, Robotics, and Autonomous Systems, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 123–147, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-control-062823-024352.

- I. Rulik et al., “Control of a Wheelchair-Mounted 6DOF Assistive Robot With Chin and Finger Joysticks,” Front. Robot. AI, vol. 9, p. 885610, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2022.885610.

- M. Pantaleoni, A. Cesta, A. Umbrico, and A. Orlandini, “Learning User Habits to Enhance Robotic Daily-Living Assistance,” in Social Robotics, vol. 13817, pp. 165–173, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-24667-8_15.

- O. Chepyk et al., “An Embedded EOG-based Brain Computer Interface System for Robotic Control,” in 2023 8th International Conference on Smart and Sustainable Technologies (SpliTech), pp. 1–6, 2023, https://doi.org/10.23919/SpliTech58164.2023.10193265.

- P. D. Lillo, D. D. Vito, and G. Antonelli, “Merging Global and Local Planners: Real-Time Replanning Algorithm of Redundant Robots Within a Task-Priority Framework,” IEEE Trans. Automat. Sci. Eng., vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 1180–1193, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/TASE.2022.3178266.

- J. Kim, M. De Mathelin, K. Ikuta, and D.-S. Kwon, “Advancement of Flexible Robot Technologies for Endoluminal Surgeries,” Proc. IEEE, vol. 110, no. 7, pp. 909–931, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2022.3170109.

- B. P. Alias and R. Bageshwar, “Flexible Precision: Design and Testing of a Snake-Inspired Robotic Arm for Large Organ and Tissue Retraction During Robot-Assisted Surgery,” in 2024 Design of Medical Devices Conference, p. V001T08A010, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1115/DMD2024-1087.

- V. Syambabu, K. Kalaiselvi, S. D. Mahil, H. S, B. Alekhya, and N. Kanagavalli, “Cutting-Edge Robotic Arm Design: Harnessing Flex Sensors and Novel Controller Framework to Meet Real-World Innovations,” in 2024 International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Cybersecurity (ISCS), pp. 1–6, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/ISCS61804.2024.10581225.

- B. Carlisle, “Flexible and Precision Assembly,” in Springer Handbook of Automation, S. Y. Nof, Ed., in Springer pp. 829–840, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96729-1_37.

- Z. Boxu et al., “Inverse Solution of 6-DOF Robot Based on Geometric Method and DH Method,” mse, 2024, https://doi.org/10.57237/j.mse.2024.01.001.

- L. Zhang, H. Du, Z. Qin, Y. Zhao, and G. Yang, “Real-time Optimized Inverse Kinematics of Redundant Robots Under Inequality Constraints,” Scientific Reports, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 29754, 2024. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-4664605/v1.

- W. Zhang, Z. Shi, X. Chai, and Y. Ding, “An Efficient Kinematic Calibration Method for Parallel Robots With Compact Multi-Degrees-of-Freedom Joint Models,” Journal of Mechanisms and Robotics, vol. 16, no. 10, p. 101011, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4064637.

- L. Mölschl, J. J. Hollenstein, and J. Piater, “Differentiable Forward Kinematics for TensorFlow 2,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.09954., 2023, https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2301.09954.

- R. K. Malhan, S. Thakar, A. M. Kabir, P. Rajendran, P. M. Bhatt, and S. K. Gupta, “Generation of Configuration Space Trajectories Over Semi-Constrained Cartesian Paths for Robotic Manipulators,” IEEE Trans. Automat. Sci. Eng., vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 193–205, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/TASE.2022.3144673.

- M. I. Rusydi, F. Akbar, A. Anandika, Syahroni, and H. Nugroho, “Combination of Biosignal and Head Movement to Control Robot Manipulator,” in 2021 6th Asia-Pacific Conference on Intelligent Robot Systems (ACIRS), pp. 1–5, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACIRS52449.2021.9519332.

- M. I. Rusydi, M. A. A. Boestari, R. Nofendra, Syafii, A. W. Setiawan, and M. Sasaki, “Wheelchair Control Based on EOG Signals of Eye Blinks and Eye Glances Based on The Decision Tree Method,” in 2024 12th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology (ICoICT), pp. 152–159, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICoICT61617.2024.10698650.

- J. P. A. Ogenga, P. W. Njeri, and J. K. Muguro, “Development of a Virtual Environment-Based Electrooculogram Control System for Safe Electric Wheelchair Mobility for Individuals with Severe Physical Disabilities,” Journal of Robotics and Control, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 165–178, 2023, https://doi.org/10.18196/jrc.v4i2.17165.

- M. S. Amri Bin Suhaimi, K. Matsushita, T. Kitamura, P. W. Laksono, and M. Sasaki, “Object Grasp Control of a 3D Robot Arm by Combining EOG Gaze Estimation and Camera-Based Object Recognition,” Biomimetics, vol. 8, no. 2, p. 208, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics8020208.

- Y. Zhou et al., “Shared Three-Dimensional Robotic Arm Control Based on Asynchronous BCI and Computer Vision,” IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng., vol. 31, pp. 3163–3175, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2023.3299350.

- K. Akhmetov, S. Atanov, K. Moldamurat, A. Baimanova, and Z. Seitbattalov, “Evaluation of the Chassis Strength of a Multi-purpose Reconnaissance Robot with Artificial Intelligence,” TU, 2024, https://doi.org/10.52209/1609-1825_2024_2_3.

- A. Rajurkar, K. Dangra, A. Deshpande, M. Gosavi, T. Phadtare, and G. Gambhire, “Comparative Finite Element Analysis of a Novel Robot Chassis Using Structural Steel and Aluminium Alloy Materials,” EI, vol. 7, pp. 61–73, 2023, https://doi.org/10.4028/p-45j91B.

- S. Kundu, K. Nayak, R. Kadavigere, S. Pendem, and . P., “Evaluation of positioning accuracy, radiation dose and image quality: artificial intelligence based automatic versus manual positioning for CT KUB,” F1000Res, vol. 13, p. 683, 2024, https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.150779.1.

- W. Zhu, X. Liu, and Z. Wang, “Analysis of Influencing Factors of Ground Imaging and Positioning of High-Orbit Remote Sensing Satellite,” in Methods and Applications for Modeling and Simulation of Complex Systems, vol. 1713, pp. 261–272, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-9195-0_22.

- P. Nguyen - Thanh, H. Nguyen - Quoc, T. Pham - Bao, L. Vuong - Cong, H. Truong - Viet, and V. Nguyen - Quang, “Improving The Accuracy of Robotic Arm Using A Calibration Method Based On The Inverse Kinematics Problem,” in 2024 9th International Conference on Applying New Technology in Green Buildings (ATiGB), pp. 306–311, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/ATiGB63471.2024.10717723.

- J. Hernandez-Barragan, J. Plascencia-Lopez, M. Lopez-Franco, N. Arana-Daniel, and C. Lopez-Franco, “Inverse Kinematics of Robotic Manipulators Based on Hybrid Differential Evolution and Jacobian Pseudoinverse Approach,” Algorithms, vol. 17, no. 10, p. 454, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/a17100454.

- A. M. D. E. Hassanein, A. G. M. A. Mohamed, and M. A. H. M. Abdullah, “Classifying blinking and winking EOG signals using statistical analysis and LSTM algorithm,” Journal of Electrical Systems and Inf Technol, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 44, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1186/s43067-023-00112-2.

- H. N. Jo, S. W. Park, H. G. Choi, S. H. Han, and T. S. Kim, “Development of an Electrooculogram (EOG) and Surface Electromyogram (sEMG)-Based Human Computer Interface (HCI) Using a Bone Conduction Headphone Integrated Bio-Signal Acquisition System,” Electronics, vol. 11, no. 16, p. 2561, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11162561.

Muhammad Ilhamdi Rusydi (Electrooculography and Camera-Based Control of a Four-Joint Robotic Arm for Assistive Tasks)