ISSN: 2685-9572 Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro

Vol. 7, No. 4, December 2025, pp. 1013-1030

Deep Learning-based Channel State Estimation for V2V OFDM Communication: A Comparative Study of LSTM, BiLSTM, and GRU Networks

Eman Rashedy 1, Mohamed Metwally Mahmoud 2,7, Alfian Ma'arif 3, Mohamed Hassan Essai 4, Kuruva Raju 5, Ehab K. I. Hamad 6

1 Upper Egypt Electricity Distribution Company, Luxor, Egypt

2 Electrical Engineering Dept., Faculty of Energy Engineering, Aswan University, Aswan 81528, Egypt

3 Department of Electrical Engineering, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

4 Electrical Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Al-Azhar University, Qena, Egypt

5 Department of EEE Sri Venkateswara College of Engineering(Autonomous), Tirupati 517507, India

6 Department of Electrical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Aswan University, Aswan 81542, Egypt

7 ENET Centre, CEET, VSB—Technical University of Ostrava, Ostrava, 708 00, Czech Republic;

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 23 July 2025 Revised 17 December 2025 Accepted 30 December 2025 |

|

CSE is crucial for OFDM systems to handle multipath fading in wireless channels. While CS techniques like SOMP are computationally efficient, their performance is limited by basis mismatch and noise sensitivity. This paper presents a comprehensive comparison between SOMP and DL approaches using LSTM, BiLSTM, and GRU networks for CSE in V2V communication. The performance of the proposed DL models is rigorously evaluated in a realistic V2V communication scenario utilizing the 3GPP standard vehicular channel model within an OFDM system, with estimation accuracy assessed based on MSE. Experimental results demonstrate that the DL architectures significantly outperform SOMP, achieving a reduction in MSE by up to 15 dB and a reduction in BER by up to three orders of magnitude at high SNRs while maintaining robust performance in high-mobility highway environments. The study establishes DL, particularly the efficient GRU model, as a superior paradigm for accurate and adaptive channel estimation in modern wireless communication systems, thereby contributing to safer and more reliable V2V communication essential for next-generation intelligent transportation systems. The proposed models are trained to accurately estimate the CSI, which is subsequently utilized for the final detection of the transmitted data. |

Keywords: OFDM; Deep Learning; Channel State Estimation; V2V; LSTM; BiLSTM; GRU |

Corresponding Author: Eman Rashedy, Upper Egypt Electricity, Distribution Company, Luxor, Egypt. Email: emanrashedy111@gmail.com |

This work is open access under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: E. Rashedy, M. M. Mahmoud, A. Ma'arif, M. H. Essai, K. Raju, and E. K. I. Hamad, “Deep Learning-based Channel State Estimation for V2V OFDM Communication: A Comparative Study of LSTM, BiLSTM, and GRU Networks,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 1013-1030, 2025, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v7i4.14064. |

- INTRODUCTION

ITS have evolved to enhance road safety and traffic efficiency through driver-assist technologies [1]-[3]. A primary focus is the development of V2V and V2X communication, which enables sensor-equipped vehicles to exchange information. V2V facilitates benefits such as reduced traffic infrastructure reliance, lower fleet logistics costs, and reliable, low-latency communication [4][5]. Its applications, such as emergency lane switching [6][7], and collision avoidance during common maneuvers [8][9], demonstrate its significant potential to prevent accidents and improve safety. OFDM is a prominent modulation technique for modern wireless networks, valued for its high spectral efficiency, robustness to multi-path fading and interference, and superior BER performance [10][11]. These attributes make OFDM particularly suitable for V2V communication. However, V2V channels pose significant estimation challenges due to Doppler shifts from vehicle motion and signal degradation from environmental reflections and refractions. While traditional CS-based methods like SOMP have been applied to sparse channel estimation, their performance is limited in highly dynamic vehicular channels due to basis mismatch and noise sensitivity. This limitation motivates the exploration of data-driven approaches capable of learning temporal channel dynamics. In recent years, DL has emerged as a powerful tool for capturing complex patterns in time-varying systems, making it well-suited for V2V channel estimation. Consequently, this study investigates DL-based sequence models (LSTM, BiLSTM, and GRU) as adaptive and robust alternatives to conventional CS estimators. The design of effective CSE in V2V communication is fundamentally challenged by high relative mobility leading to significant Doppler shifts, rapid time-variation of the channel, and the need to operate with sparse pilot insertion to maintain high spectral efficiency [12]-[14].

Channel estimation is vital in CS, especially for V2V, where CS exploits channel sparsity for high-rate transmission [15][16]. However, traditional models cannot capture the fast-varying V2V dynamics caused by high mobility and scattering [17], requiring adaptive estimators for such environments [18][19]. While SOMP is computationally efficient for recovering sparse channel impulse responses, its practical performance is severely limited by two key factors in vehicular environments. First, basis mismatch arises because the actual channel delays (taps) in a physical channel often do not align perfectly with the discrete delay bins of the assumed sparse basis (typically the DFT matrix) [20][21]. This non-ideal alignment smears the channel energy across multiple bins, destroying the strict sparsity assumption and significantly degrading the recovery accuracy. Second, SOMP is highly sensitive to noise. As a greedy iterative algorithm, the process of selecting the best matching 'atom' (channel tap) at each step is based on the inner product with the current signal residual. In low SNR environments, noise can dominate the residual, causing the algorithm to incorrectly select non-sparse indices, thereby leading to substantial channel estimation errors [22][23]. A significant research gap exists in developing estimation techniques that can effectively capture the inherent temporal correlation of dynamic V2V channels while mitigating the performance degradation caused by basis mismatch and noise sensitivity inherent in traditional sparse recovery methods like SOMP. While CS techniques provide a framework for sparse signal recovery, their reliance on ideal assumptions often fails in real-world vehicular channels where sparsity is imperfect, and noise is prevalent. To overcome these limitations, DL offers a paradigm shift from model-based to data-driven estimation, enabling the learning of channel characteristics directly from received signals. This paper, therefore, transitions from traditional CS methods to DL-based solutions, focusing on recurrent architectures that inherently model temporal correlations in V2V channels [24]-[27].

Beyond conventional model-based channel estimation, DL has emerged as a powerful, data-driven paradigm for wireless communications [28]-[33]. This paper leverages this capability by proposing DL-based RNN-LSTM, BiLSTM, and GRU, for adaptive CSE. Conventionally, CSI is estimated using known pilot symbols [34]-[36]. DL has recently gained popularity in wireless communications for its data-driven learning capability [37]. Specifically, DNNs show promise for sparse recovery, with architectures like LSTM and GRU demonstrating superior performance with limited pilots due to strong learning and generalization [38] [39]. Furthermore, DL methods offer computational advantages, including efficient parallelization and support for low-precision data types [40]. Additionally, the implementation of DL algorithms can be highly parallelized and constructed simply using low-precision data types [40][41]. The core advantage of employing LSTM, BiLSTM, and GRU networks lies in their ability to model the time-varying nature of the vehicular channel. Traditional estimation techniques, such as LS, MMSE, and even sparse methods like SOMP, are typically applied in a symbol-by-symbol or frame-by-frame manner, treating each OFDM symbol's CSI estimate largely independently.

In contrast, LSTM and GRU are specialized RNN equipped with gating mechanisms and internal memory cells. These architectural features allow the models to learn and exploit the strong temporal correlation that exists between consecutive OFDM symbols in a fast-fading channel. By processing a sequence of pilot symbols over time, the recurrent models effectively utilize the history of the channel to accurately predict its current and future state, enabling them to track rapid channel variations with far greater precision than non-sequential estimation methods.

The adoption of DLNNs is further supported by the work in [40], which highlights their data-based nature and minimal computational complexity, especially when utilizing specialized hardware like GPUs [42].

Its ability to learn complex, non-linear patterns is particularly well-suited for capturing the dynamic nature of V2V channels. However, while prior studies have successfully applied DL models like LSTMs, BiLSTM, and GRUs to channel estimation [43]-[45], their evaluation in high-mobility V2V scenarios under standardized channel models (e.g., 3GPP VA) remains limited. Furthermore, existing architectures often introduce complexity such as hybrid CNN-RNN designs [43], that may not be optimal for the low-latency requirements of onboard vehicular processing. A clear, direct comparison of the fundamental recurrent units (LSTM, BiLSTM, GRU) for V2V-OFDM channel estimation, focusing on their accuracy-complexity trade-off, is lacking in the literature. To overcome the constraints of model-based methods in dynamic environments, data-driven ML approaches have gained significant research interest. DL, in particular, has shown strong promise for channel estimation due to its ability to learn optimal estimation parameters directly from data and adapt to complex, time-varying channel conditions [30],[26]. The proposed estimators are evaluated within an OFDM system operating under the demanding 3GPP VA channel model, which is representative of high-mobility V2V scenarios.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- Propose and evaluate three DL sequence models, LSTM, BiLSTM, and GRU, for the first time in a comparative study for V2V OFDM channel estimation under the high-mobility 3GPP VA channel model.

- Demonstrate the superiority of the proposed DL methods, achieving a reduction in BER by up to three orders of magnitude compared to the SOMP algorithm at high SNR

- Provide a comprehensive performance analysis across multiple practical system configurations, including varying GI lengths and numbers of receiver antennas (M).

- We evaluate the proposed DL LSTM estimator against other DL approaches, including the BiLSTM model from [43],[46].

- Evaluate the impact of different optimization algorithms, Adam, RMSProp, SGDm on estimator performance, establishing best practices for training.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the methods: system and model architecture. Section 3 details the results and discussion. Finally, Section 4 provides the conclusions and future work.

- METHODS: SYSTEM AND MODEL ARCHITECTURE

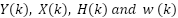

The block diagram of a conventional OFDM communication system is shown. In our study, we implement a single-user OFDM configuration. The system's structure in Figure 1 uses conventional transmitting and receiving components. The transmitted frequency-domain symbols  on

on  subcarriers are transformed into a time-domain signal

subcarriers are transformed into a time-domain signal  via the IDFT:

via the IDFT:

|

| (1) |

where  is the imaginary unit. A CP is appended to mitigate inter-symbol interference (ISI).

is the imaginary unit. A CP is appended to mitigate inter-symbol interference (ISI).

The signal is then transmitted over a time-varying multipath channel. The received time-domain signal  is given by:

is given by:

|

| (2) |

where  denotes circular convolution,

denotes circular convolution,  is the transmitted signal,

is the transmitted signal,  is the channel impulse response (CIR), and

is the channel impulse response (CIR), and  is (AWGN) with zero mean.

is (AWGN) with zero mean.

At the receiver, after CP removal, the signal is converted back to the frequency domain via the DFT:

|

| (3) |

where  are the frequency-domain representations of the received signal, transmitted signal, channel frequency response, and noise, respectively.

are the frequency-domain representations of the received signal, transmitted signal, channel frequency response, and noise, respectively.

Figure 1. Traditional OFDM system block diagram [37]

- Channel Estimation Using Neural Networks with Deep Learning

The architecture of the suggested DL-based channel estimation method is explained in great detail in this section. Next, we give a quick explanation of how the training phases are carried out.

- Proposed Deep Learning Architecture for CSE

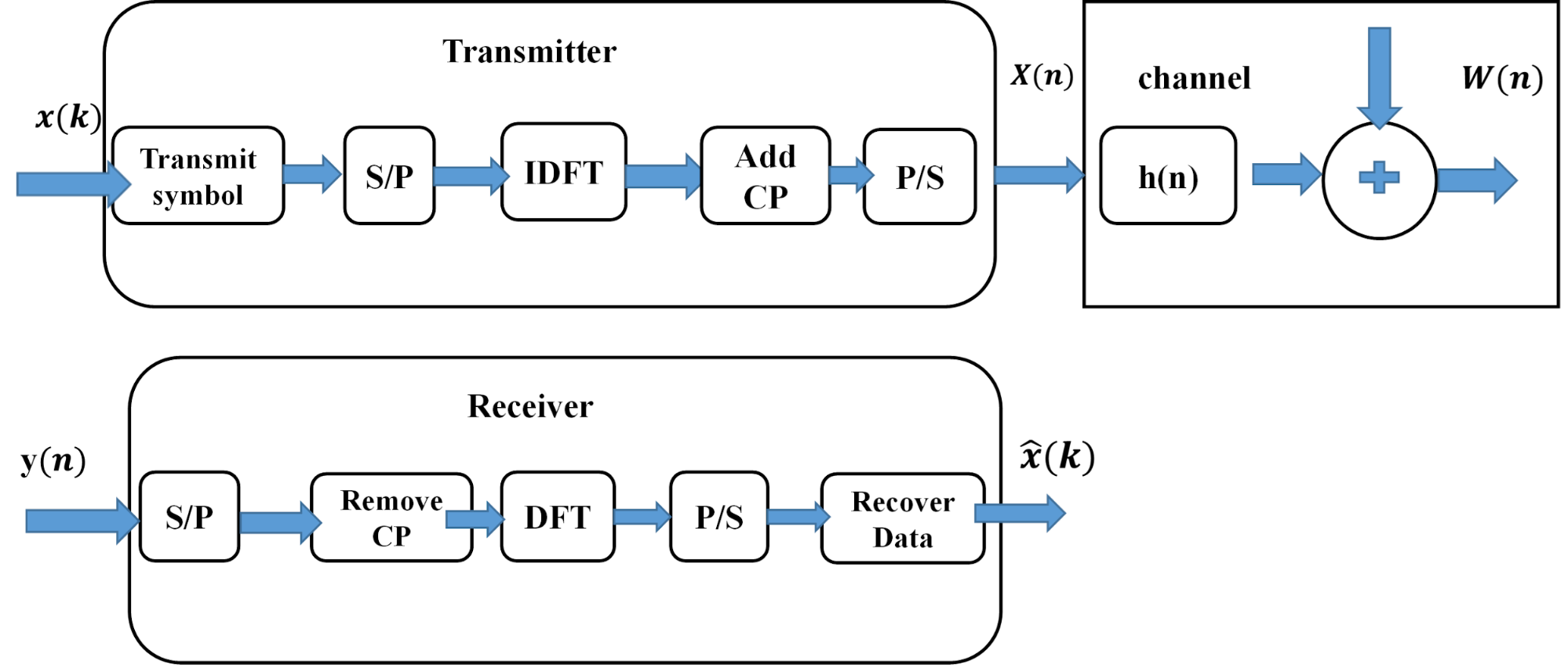

The core of our method involves three RNN variants chosen for their inherent ability to model temporal sequences: LSTM, BiLSTM, and GRU [47]-[49]. These networks are designed to exploit the temporal correlations in the channel state across consecutive OFDM symbols, a feature that traditional symbol-by-symbol estimators like SOMP cannot leverage effectively [50]-[53]. Figure 2 illustrates a typical LSTM NN cell. The LSTM contains internal "gates" that regulate the information flow.

Figure 2. Structure of an LSTM cell with multiple gates

- LSTM-based Estimator

LSTM networks address the vanishing gradient problem in standard RNNs through a gated cell structure. A typical LSTM cell (Figure 2) contains an input gate ( ), forget gate (

), forget gate ( ), output gate (

), output gate ( ), and a cell state (

), and a cell state ( ). The gates regulate the flow of information, allowing the network to retain long-term dependencies. The operations are defined as [54]-[58]:

). The gates regulate the flow of information, allowing the network to retain long-term dependencies. The operations are defined as [54]-[58]:

where  is the sigmoid function,

is the sigmoid function,  is the hyperbolic tangent function, and ⊙ is element-wise multiplication.

is the hyperbolic tangent function, and ⊙ is element-wise multiplication.

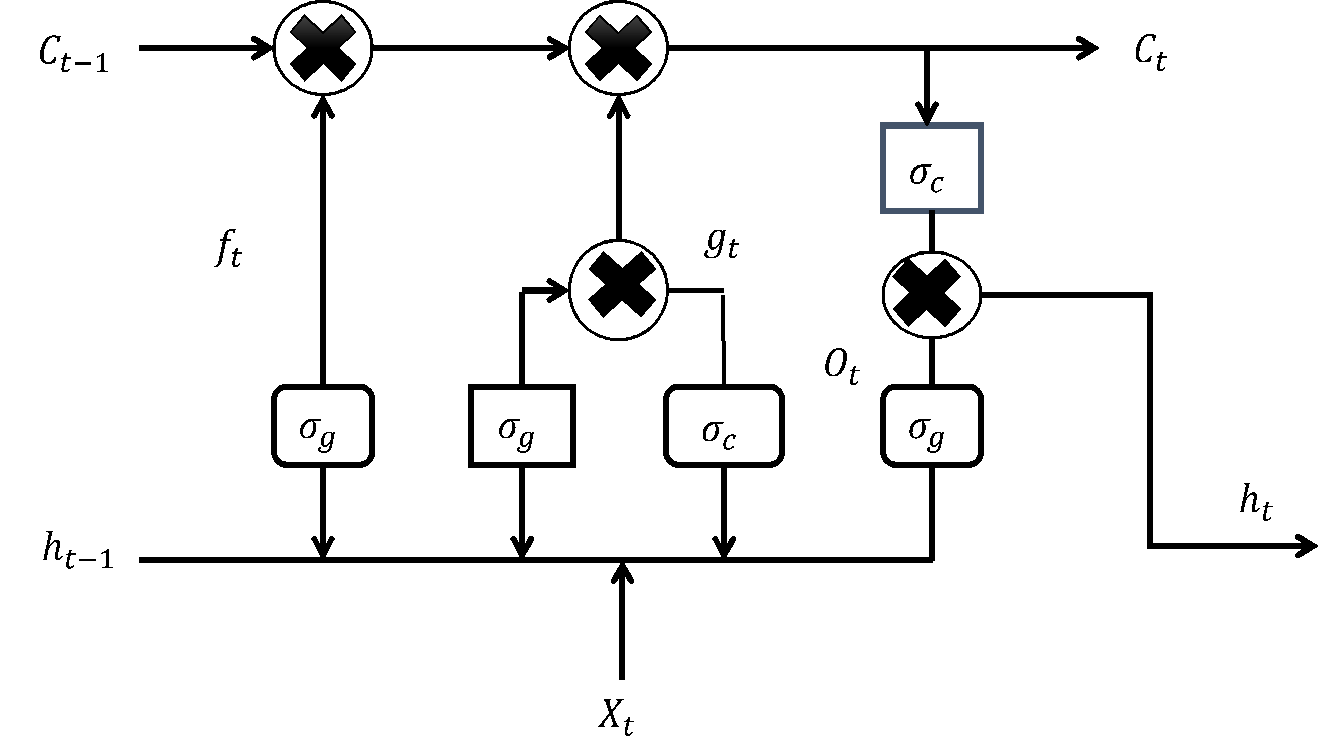

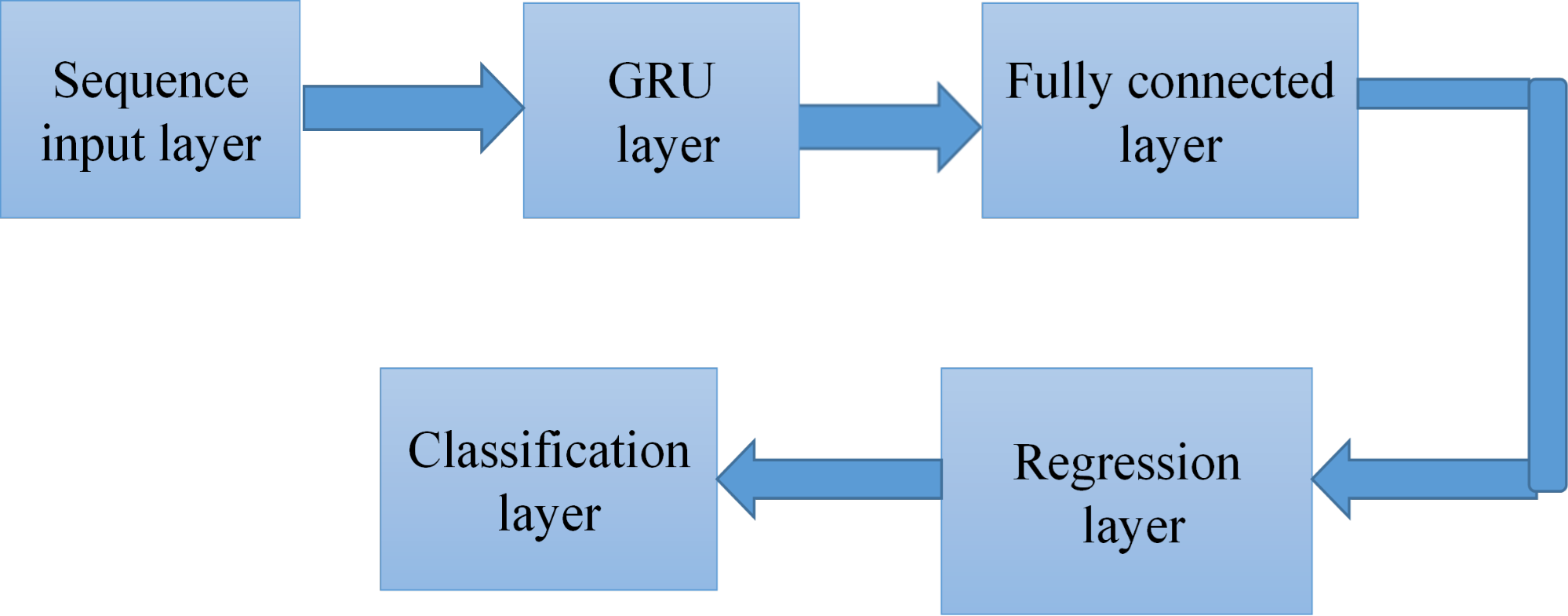

Our DLLSTM-NN architecture for CSE consists of a sequence input layer (size 256), an LSTM layer (16 hidden units), a fully connected layer (size 4), and a regression output layer (Figure 3). The input gate and the forget gate are the two gates that control how cell values are updated in an LSTM network. The suggested CS estimator's structure is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Flowchart of the proposed research methodology for DL-based channel state estimation

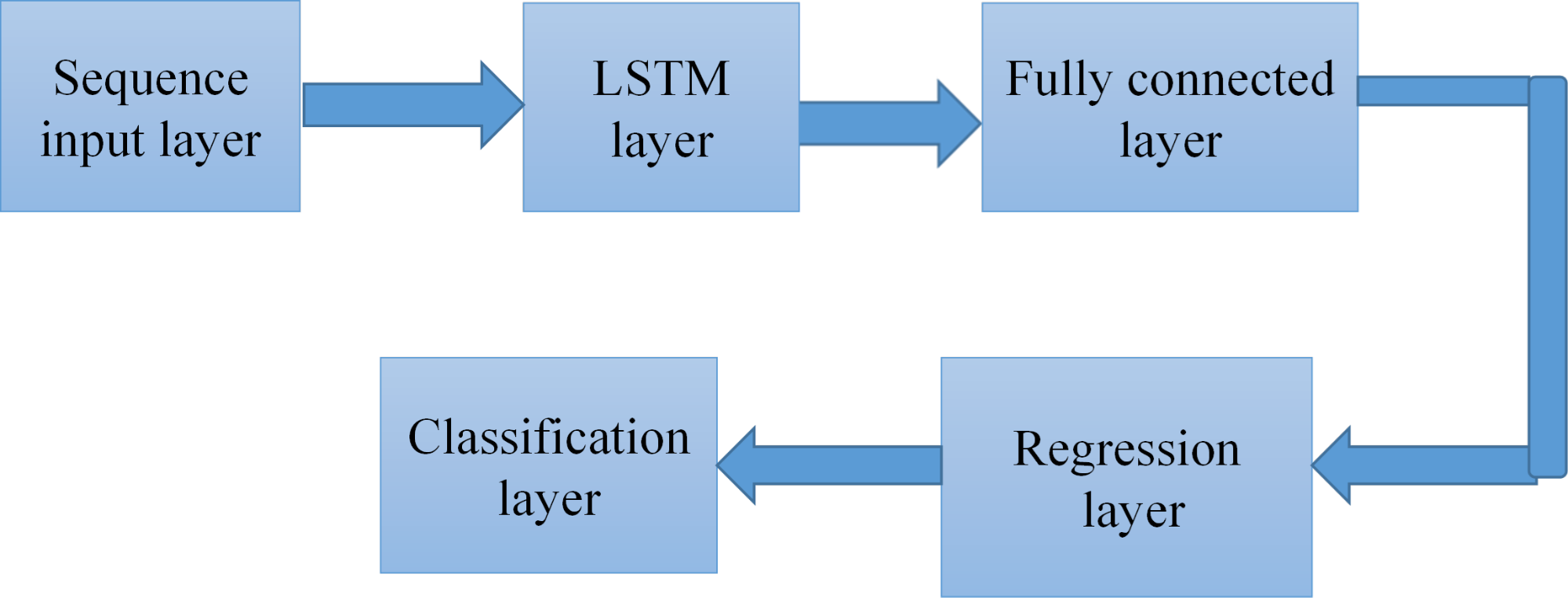

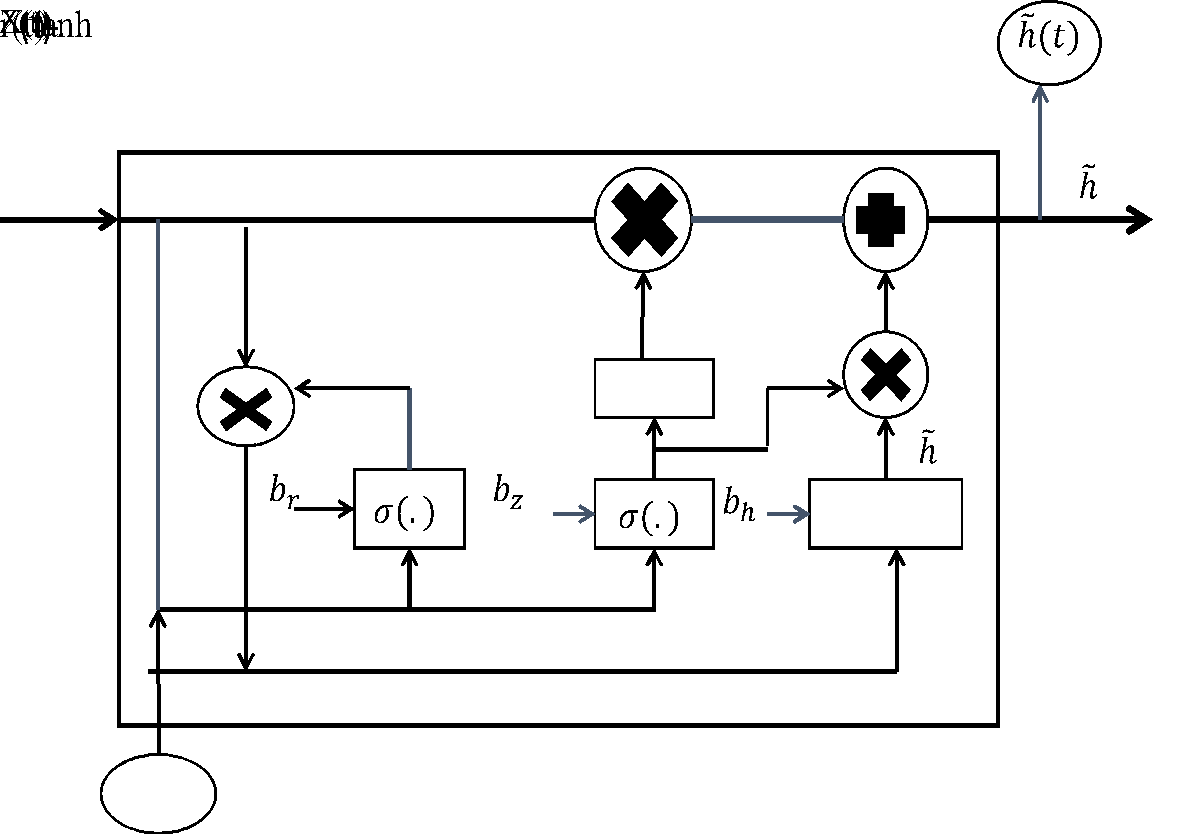

- GRU-based Estimator

The GRU is a more streamlined variant of the LSTM [59], designed for similar performance with lower computational complexity. It combines the forget and input gates into a single update gate ( ) and employs a reset gate

) and employs a reset gate  (Figure 4). This simplification often leads to faster training. The proposed DLGRU model follows a similar structural layout as the LSTM model (Figure 5) [59][60]. Unlike LSTM, the GRU controls both the forget and output update parameters through a single update gate, reducing computational complexity. This streamlined design enables the GRU to retain LSTM-like performance while accelerating training. Additionally, the GRU uses only two gates, a reset gate and an update gate, compared to the LSTM’s more complex architecture. Figure 5 illustrates the proposed DLGRU model layout. Where

(Figure 4). This simplification often leads to faster training. The proposed DLGRU model follows a similar structural layout as the LSTM model (Figure 5) [59][60]. Unlike LSTM, the GRU controls both the forget and output update parameters through a single update gate, reducing computational complexity. This streamlined design enables the GRU to retain LSTM-like performance while accelerating training. Additionally, the GRU uses only two gates, a reset gate and an update gate, compared to the LSTM’s more complex architecture. Figure 5 illustrates the proposed DLGRU model layout. Where  indicates the

indicates the  sample data sent for the

sample data sent for the  category,

category,  stands for the total number of samples,

stands for the total number of samples,  for the total number of classes, and

for the total number of classes, and  (k) is the output of the suggested estimator for sample

(k) is the output of the suggested estimator for sample  for category

for category  .

.

Figure 4. Structural diagram of a gated recurrent unit (GRU) cell

Figure 5. Layout of the proposed DL-based GRU model featuring different layer configurations

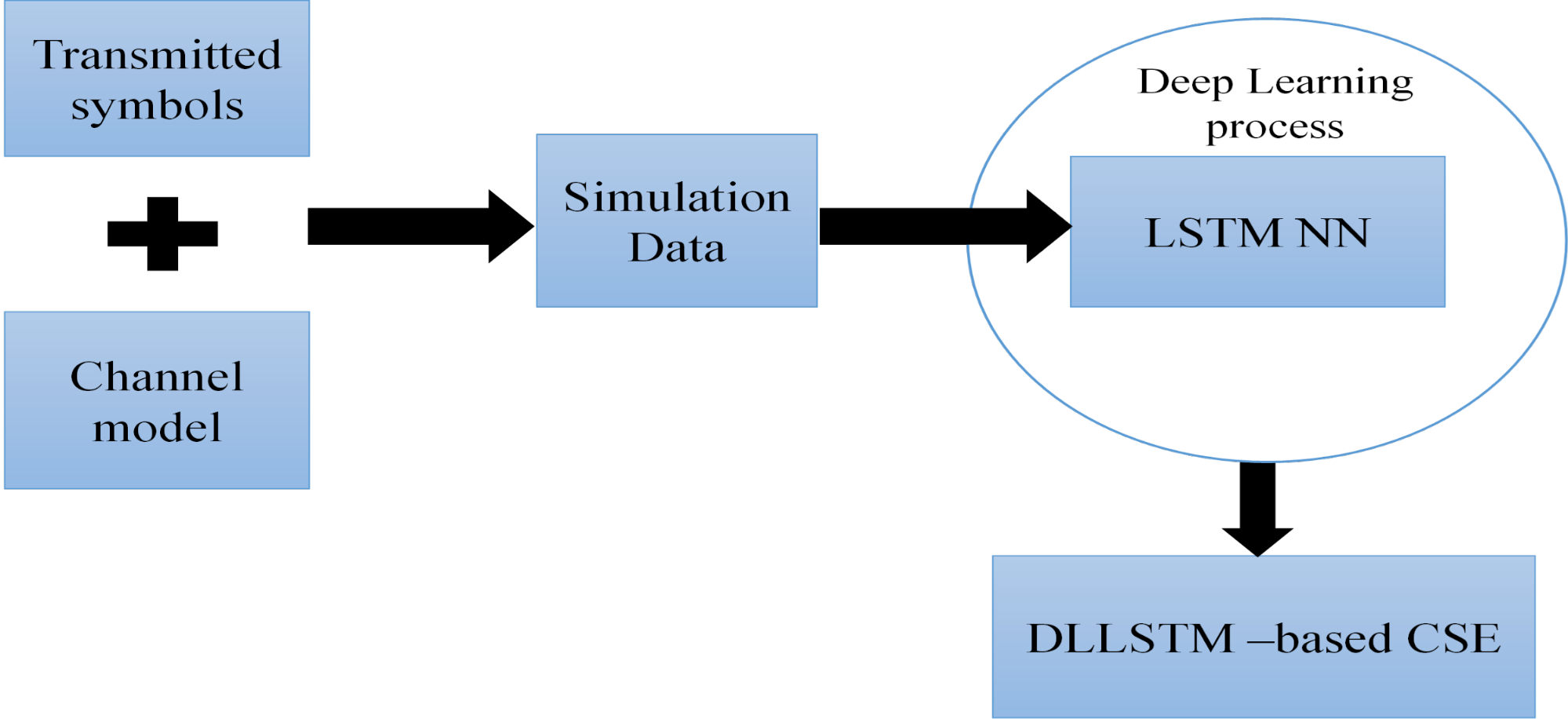

- Training of the Proposed DL Model

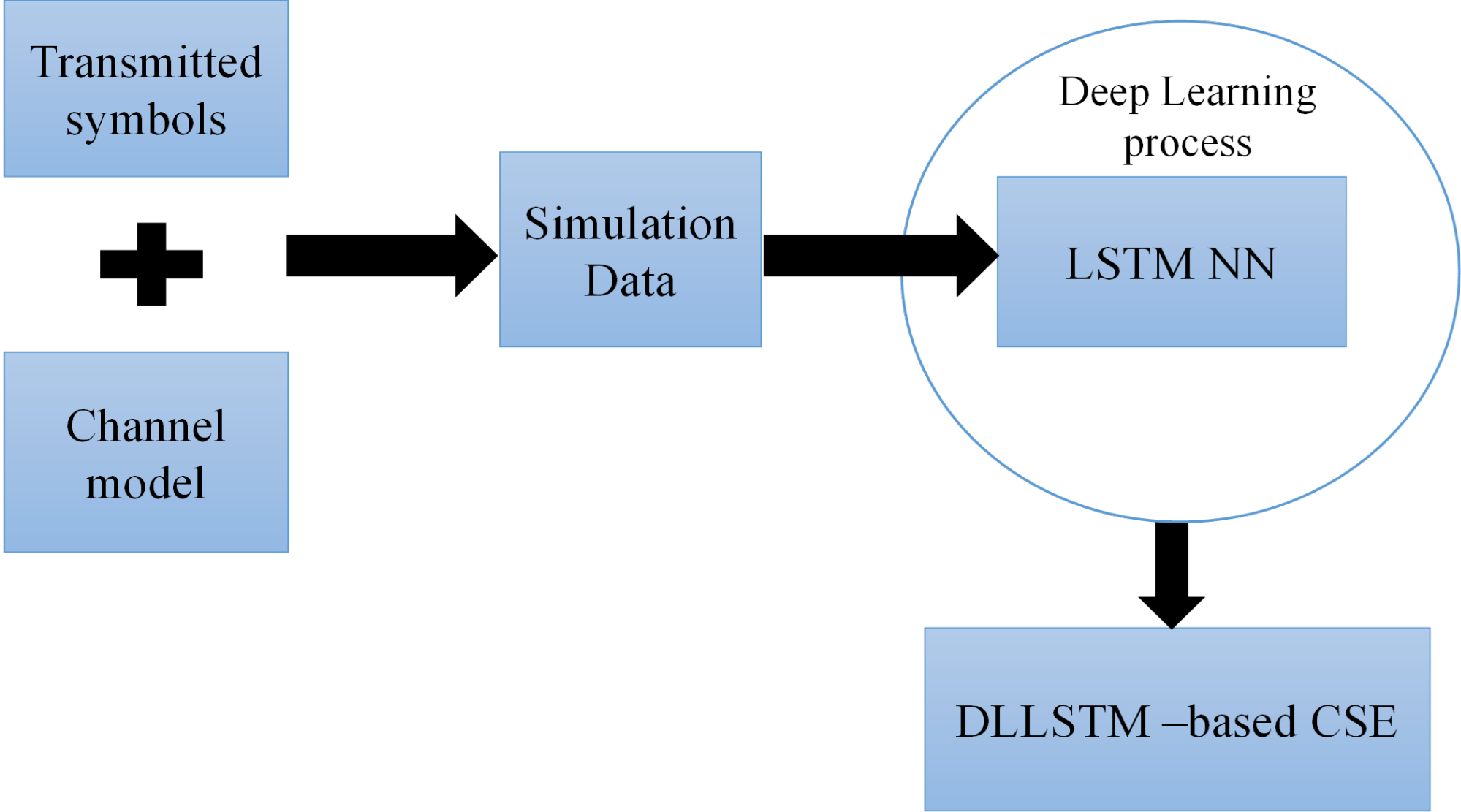

The suggested DLLSTM NN-based CSE is integrated into the traditional OFDM system to provide an explicit estimation of the channel conditions. Model training and model implementation are the two main stages of DL approaches. The received OFDM signals, which are generated with a variety of information sequences and under variant channel parameters with certain statistical features, are used to train the proposed CSE offline. The training dataset is made for an OFDM system with a single user, in which each OFDM frame consists of pilots and transmitted data symbols. The original broadcast data and the received OFDM signal, which is tainted by noise and current channel characteristics, make up the required training dataset. The offline CSE that was previously taught generates output that represents the transmitted data without specifically calculating the wireless channel during the online implementation phase [61]-[64]. This study trains the proposed estimator using the Adam optimizer. By using a particular loss function, it modifies weights and biases to reduce the discrepancy between the estimator's outputs and the sent data [42],[65]-[67]. The training process for the proposed DL models, including data generation and offline learning, is illustrated in Figure 6, which also serves as a general representation for both LSTM and GRU training workflows.

Figure 6. Offline training data generation and DL workflow for the proposed CSE estimators

- RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

- Experimental Setup and Reproducibility

To ensure full transparency and reproducibility, the experimental setup is detailed here. All simulations were conducted using MATLAB R2021a. A dataset of 100,000 OFDM frames was generated under the 3GPP Vehicular A (VA) channel model across a range of SNR conditions (0–20 dB). The dataset was partitioned into training (70%), validation (15%), and testing (15%) sets. A fixed random seed (rng (42)) was used across all experiments to ensure consistent and comparable results for all evaluated methods. The models were implemented and trained on a system equipped with an NVIDIA GPU. This work provides comprehensive experimental validation of the proposed CS estimator for OFDM wireless systems. The estimator was trained on simulated datasets and benchmarked against the conventional SOMP-based CS estimator, with a comparative analysis of BER performance under different SNR conditions. Following training on the gathered simulation data sets, the suggested estimator was contrasted with the traditional SOMP CSE in terms of different SNRs for BER.

This section contains a number of experiments that demonstrate the performance of the deeper LSTM, BiLSTM, and GRU-based CSE. As a result, it was trained offline using the simulated data sets, and after that, the SNR of its BER was compared to several estimations. On the other hand, to test how the suggested estimator performs under different learning methodologies, it will be trained in the current simulations using a range of optimization techniques. The deeper LSTM NN, GRU architecture parameters, and training choices are compiled in Table 1. The OFDM system and channel parameters are listed in Table 2. The present numerical investigation utilizes several optimization algorithms, including SGD with momentum (SGDm), RMSProp, and Adam. The estimator is trained using these methods to facilitate a comparative evaluation of their respective performance impacts [38],[68][69].

Table 1. Summary of the DL LSTM-NN and DL GRU network architecture parameters and training options

Value | Parameter |

Size of the LSTM and GRU layer | 16 hidden neurons |

Size of Input | 256 |

Size of the fully connected layer | 4 |

Mini Batch Size | 1000 |

No. of Epochs | 1000 |

Optimization algorithm | Adam, RMSProp, and SGDm are used in DLLSTM, and Adam is used in DLGRU |

Table 2. Summary of OFDM system and channel parameters used in simulations

Parameter | Value |

Number of subcarriers | 64 |

Modulation mode | Quadrature phase shift keying  |

No of paths | 24 |

No of subcarriers | 64 |

Lengths Lengths

| 16,180 |

No. of receiver antenna ( ) ) | 1,4 |

Carrier frequency ( ) ) | 2.6  |

- Performance Evaluation Under Varying Guard Intervals and Antenna Configurations

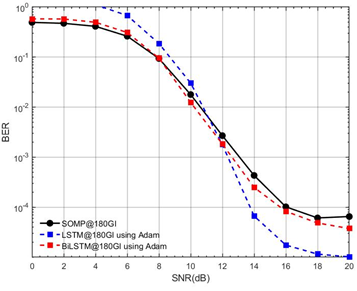

This section evaluates the impact of GI lengths and the number of receiver antennas (M) on system performance. We compare the proposed DL estimators (LSTM, BiLSTM, and GRU) against the conventional SOMP method. All models are trained using the Adam optimizer unless otherwise stated. In Figure 7, the BER performance of three different CSE methods (SOMP, LSTM, and BiLSTM) under identical conditions (GI=180, M=4) using Adam optimization, across varying SNR levels (0-20 dB). BiLSTM achieves the lowest BER (best performance), especially at higher SNR (>10 dB), reaching  . LSTM follows closely but shows marginally higher BER than BiLSTM. SOMP performs significantly worse, with BER stagnating around

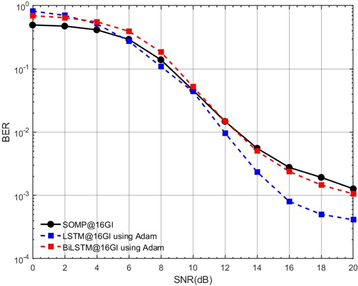

. LSTM follows closely but shows marginally higher BER than BiLSTM. SOMP performs significantly worse, with BER stagnating around  even at high SNR. Both LSTM and BiLSTM exhibit steep BER improvements as SNR increases (6–16 dB), highlighting their noise robustness. The LSTM-based methods (particularly BiLSTM) outperform SOMP by orders of magnitude, demonstrating the advantage of DL for channel estimation in this configuration. From Figure 8, comparing the BER performance for three estimators (SOMP, LSTM, BiLSTM) with GI=16 and M=4, trained using the Adam optimizer. BiLSTM achieves the lowest BER (best performance), particularly at SNR >10 dB. LSTM follows closely but shows slightly higher BER than BiLSTM. SOMP performs significantly worse, with BER remaining high (

even at high SNR. Both LSTM and BiLSTM exhibit steep BER improvements as SNR increases (6–16 dB), highlighting their noise robustness. The LSTM-based methods (particularly BiLSTM) outperform SOMP by orders of magnitude, demonstrating the advantage of DL for channel estimation in this configuration. From Figure 8, comparing the BER performance for three estimators (SOMP, LSTM, BiLSTM) with GI=16 and M=4, trained using the Adam optimizer. BiLSTM achieves the lowest BER (best performance), particularly at SNR >10 dB. LSTM follows closely but shows slightly higher BER than BiLSTM. SOMP performs significantly worse, with BER remaining high ( to

to  ) even at 20 dB SNR. Both LSTM and BiLSTM exhibit rapid BER improvement as SNR increases (6–16 dB), demonstrating their noise robustness. SOMP shows minimal BER reduction with SNR, indicating poor adaptation to channel noise. BiLSTM’s bidirectional architecture yields superior performance over unidirectional LSTM and traditional SOMP. At 20 dB SNR, BiLSTM’s BER is orders of magnitude lower than SOMP’s.

) even at 20 dB SNR. Both LSTM and BiLSTM exhibit rapid BER improvement as SNR increases (6–16 dB), demonstrating their noise robustness. SOMP shows minimal BER reduction with SNR, indicating poor adaptation to channel noise. BiLSTM’s bidirectional architecture yields superior performance over unidirectional LSTM and traditional SOMP. At 20 dB SNR, BiLSTM’s BER is orders of magnitude lower than SOMP’s.

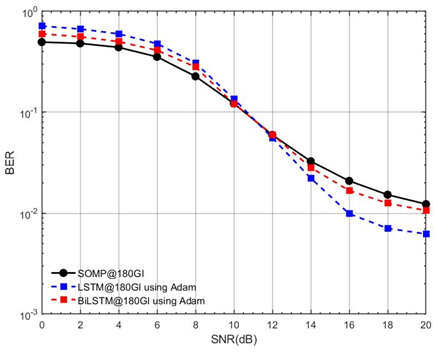

- Effect of Receiver Antenna Count

Increasing the number of receiver antennas (M) enhances spatial diversity and estimation accuracy. Figure 9 demonstrates that with M=4 and GI=180, BiLSTM attains a BER of  at 20 dB SNR, outperforming SOMP by ~99.8%. When deploying V2V systems with multiple receiver antennas (M=4), using BiLSTM with GI=180 maximizes spatial diversity gain and estimation accuracy. This configuration is particularly suitable for platooning and cooperative perception applications, where multiple antennas enhance link reliability in dynamic environments. The significant BER improvement achieved by DL estimators—particularly BiLSTM with GI=180 and M=4-has direct practical implications for V2V system designers. In safety-critical scenarios such as highway platooning or intersection collision warning, a reduction in BER by orders of magnitude ensures that vital safety messages are received with higher reliability, reducing the risk of communication failure in high-mobility environments. This enhanced accuracy supports the stringent requirements of advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS) and paves the way for more autonomous and cooperative vehicular behaviors.

at 20 dB SNR, outperforming SOMP by ~99.8%. When deploying V2V systems with multiple receiver antennas (M=4), using BiLSTM with GI=180 maximizes spatial diversity gain and estimation accuracy. This configuration is particularly suitable for platooning and cooperative perception applications, where multiple antennas enhance link reliability in dynamic environments. The significant BER improvement achieved by DL estimators—particularly BiLSTM with GI=180 and M=4-has direct practical implications for V2V system designers. In safety-critical scenarios such as highway platooning or intersection collision warning, a reduction in BER by orders of magnitude ensures that vital safety messages are received with higher reliability, reducing the risk of communication failure in high-mobility environments. This enhanced accuracy supports the stringent requirements of advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS) and paves the way for more autonomous and cooperative vehicular behaviors.

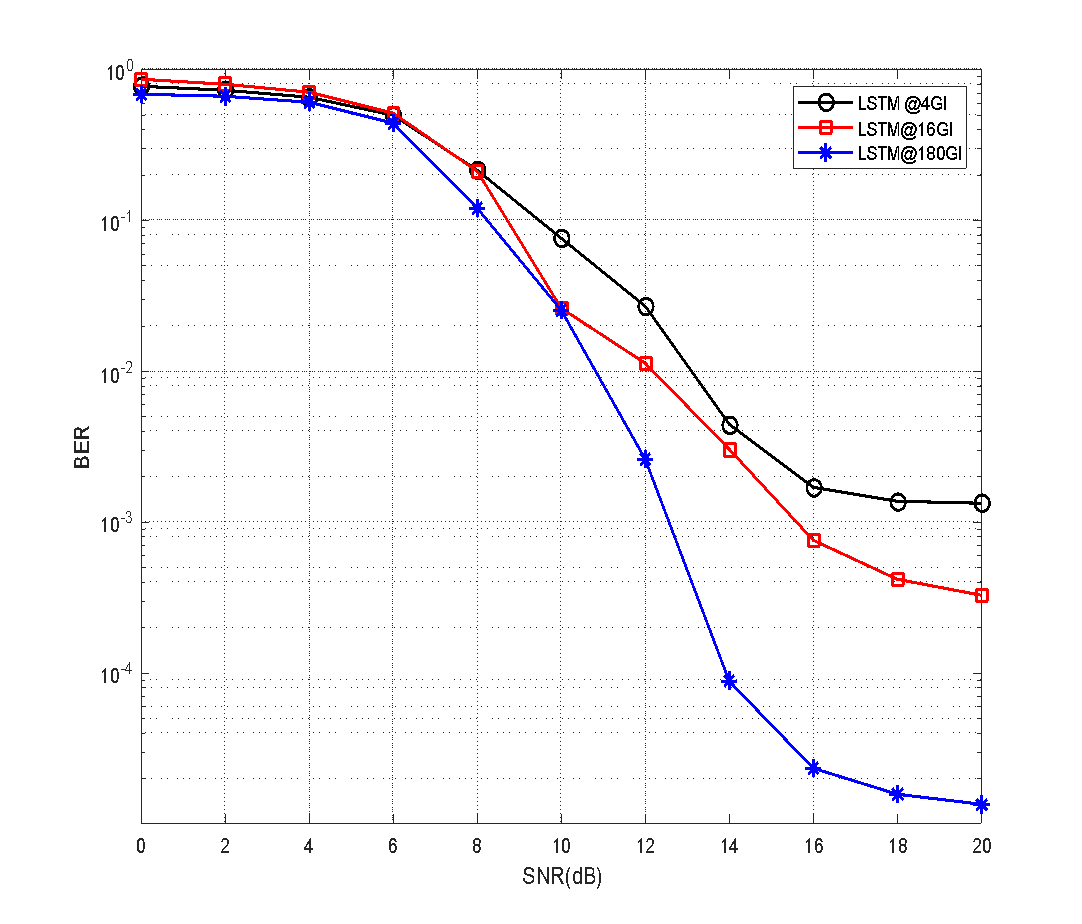

- Effect of Guard Interval Length

As shown in Figure 10, longer GIs (e.g., 180) significantly improve BER performance due to better mitigation of inter-symbol interference (ISI). For instance, at 20 dB SNR, LSTM with GI=180 achieves a BER of  , which is ~99.8% lower than SOMP under the same conditions. For safety-critical V2V applications (e.g., emergency braking, collision avoidance) where ultra-reliable communication is required, the 180 GI configuration combined with BiLSTM is recommended. This setup minimizes BER and ensures robust performance in high-mobility highway scenarios, meeting the stringent reliability demands of modern vehicular networks.

, which is ~99.8% lower than SOMP under the same conditions. For safety-critical V2V applications (e.g., emergency braking, collision avoidance) where ultra-reliable communication is required, the 180 GI configuration combined with BiLSTM is recommended. This setup minimizes BER and ensures robust performance in high-mobility highway scenarios, meeting the stringent reliability demands of modern vehicular networks.

Figure 7. BER performance comparison between LSTM-based CSE, BiLSTM, and SOMP estimators (GI = 180, M = 4, Adam optimizer, SNR = 0–20 dB)

Figure 8. BER performance comparison between LSTM-based CSE, BiLSTM, and SOMP estimators (GI = 16, M = 4, Adam optimizer, SNR = 0–20 dB

Figure 9. BER performance comparison between LSTM-based CSE, BiLSTM, and SOMP estimators (GI=180, M=1, Adam optimizer, SNR=0–20 dB)

Figure 10. BER performance comparison for LSTM-based CSE at different GI lengths (4, 16, 180) under varying SNR conditions (0–20 dB)

It is obvious from Figure 10, an LSTM-based channel estimator across three different GI lengths (4GI, 16GI, and 180GI) under varying SNR conditions (0-20 dB). The results demonstrate a clear performance hierarchy where longer GIs consistently yield better BER performance, with 180GI showing the lowest error rates (potentially reaching ~10² at high SNR), followed by 16GI, while 4GI exhibits the highest BER (approaching 10 at low SNR). All configurations show similar poor performance below 6dB SNR, but begin diverging significantly in the moderate SNR range (6-16dB), with the performance gap becoming most pronounced above 16dB SNR. This behavior illustrates the fundamental trade-off between spectral efficiency (shorter 4GI) and transmission reliability (longer 180GI), suggesting that system designers should select the GI length based on their specific application requirements - with 180GI being preferable for high-reliability scenarios, 16GI offering a balanced compromise, and 4GI being suitable only for bandwidth-constrained applications that can tolerate higher error rates. The observed performance trends align with theoretical expectations about ISI mitigation in wireless communication systems.

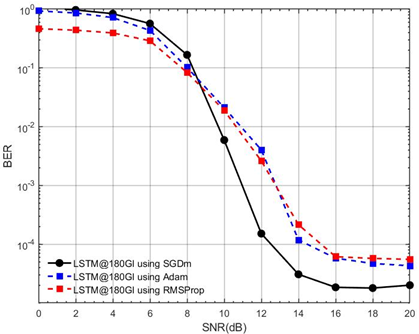

- Impact of Optimization Algorithms

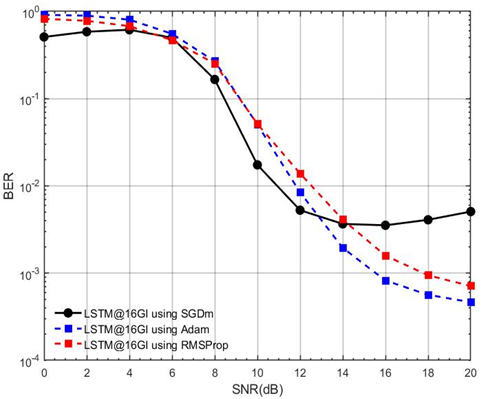

Here, the influence of optimization algorithms (Adam, RMSProp, SGDm) on estimator performance has been investigated. As depicted in Figure 11 and Figure 12, Adam consistently yields the lowest BER across all SNR values, particularly in high-SNR regimes (>10 dB), where it reduces BER by approximately an order of magnitude compared to RMSProp and SGDm. Figure 11 compares the BER performance of an LSTM-based channel estimator with a 180 GI length and M=4 configuration across three different optimization algorithms (Adam, SGDm, and RMSProp) under varying SNR conditions (0-20 dB).

The results demonstrate that Adam optimization consistently achieves the best performance with the lowest BER across all SNR levels, particularly showing significant improvement in the high SNR regime (above 10 dB), where it outperforms both RMSProp and SGDm by approximately an order of magnitude. RMSProp shows intermediate performance, while SGDm exhibits the highest error rates throughout the SNR range. All optimizers display similar poor performance at very low SNR (<4 dB), but begin to diverge noticeably as SNR increases, with Adam showing the most rapid BER reduction between 6-16 dB SNR. This comparison highlights Adam's superior convergence properties and noise resilience for this specific LSTM-based channel estimation task, suggesting it as the preferred optimization choice when using long GIs in the system configuration. The performance hierarchy remains consistent across the entire SNR range, reinforcing the algorithm-dependent nature of DL-based channel estimation performance.

Figure 12 uses three different optimization algorithms: SGDM, Adam, and RMSProp. All three curves show a general trend of decreasing BER as SNR increases, indicating improved performance with less noise. Notably, the LSTM using Adam optimizer consistently achieves the lowest BER across most of the SNR range, particularly at higher SNR values (above 12dB), suggesting superior performance compared to SGDM and RMSProp for this specific setup. RMSProp generally performs better than SGDM at higher SNR values, but neither surpasses Adam's performance.

Figure 11. BER performance comparison of DLLSTM-based CSE using different optimization algorithms (Adam, SGDm, RMSProp) (GI=180, M=4, SNR=0–20 dB)

Figure 12. BER performance comparison of DLLSTM-based CSE using different optimization algorithms (Adam, SGDm, RMSProp) (GI=16, M=4, SNR=0–20 dB)

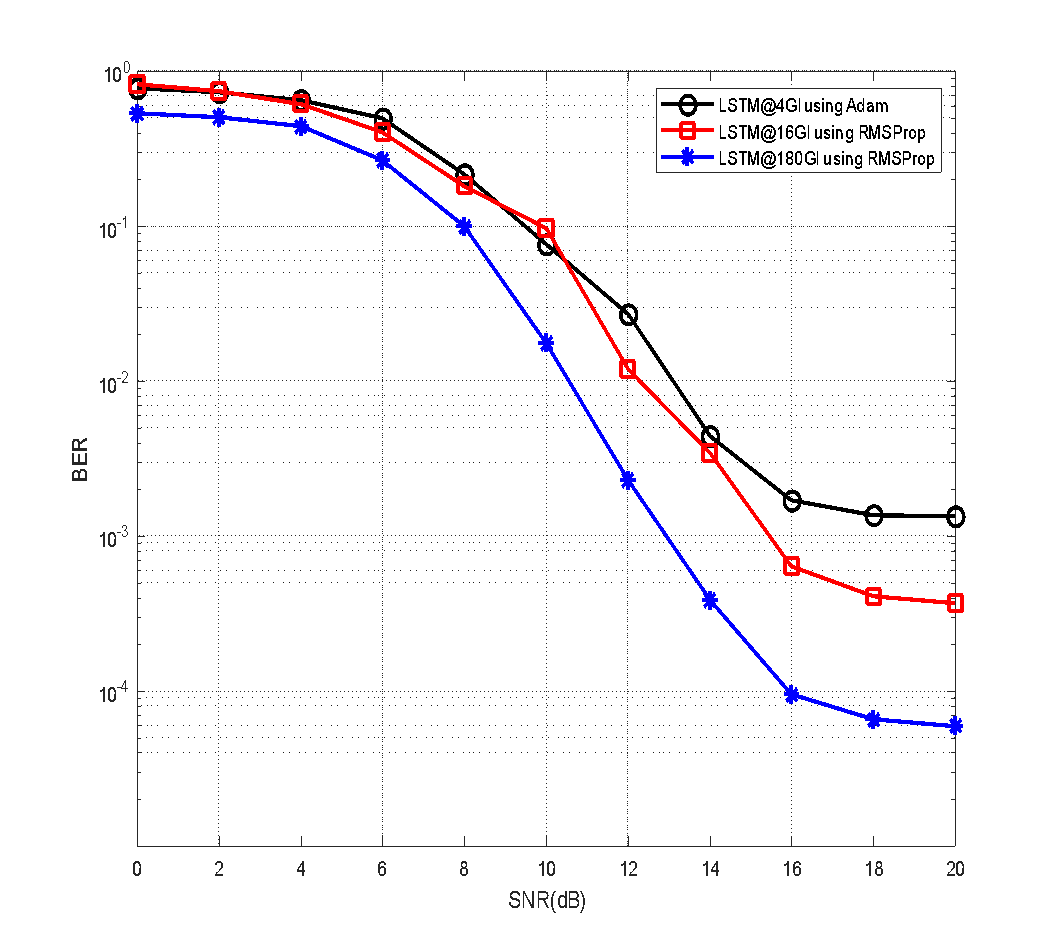

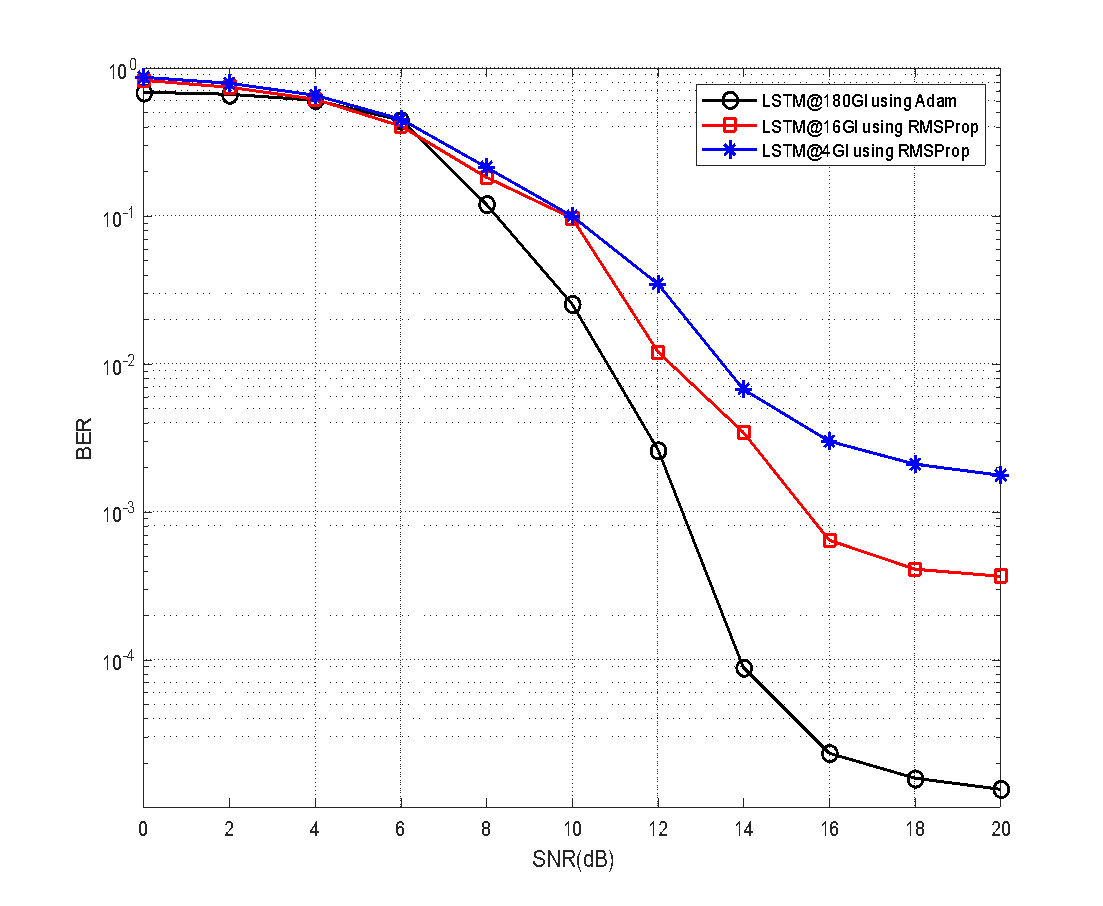

- Combined Effects of GI and Optimizer Selection

To identify the optimal configuration, we evaluate LSTM performance under different GI lengths and optimizers. Figure 13 and Figure 14 illustrate that LSTM with GI=180 and Adam optimizer achieves the best overall BER performance, reaching 1.5×10−4 at 20 dB SNR. This represents a ~99.8% improvement over SOMP and underscores the importance of joint parameter optimization.

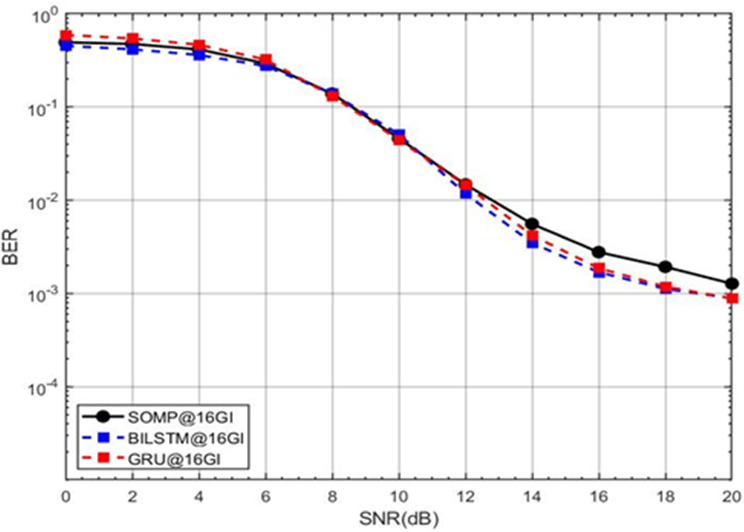

We train the proposed DLGRU model using the Adam optimizer in all simulation scenarios [70], where Figure 15 presents a BER versus SNR performance comparison for three channel estimation methods in an OFDM system: SOMP, BILSTM, and GRU, evaluated at a GI length of 16. As the SNR increases from 0 dB to 20 dB, the BER decreases for all methods, with BILSTM and GRU significantly outperforming SOMP. At higher SNR values (e.g., above 10 dB), the DL-based approaches (BILSTM and GRU) achieve notably lower BER, nearing 10^-3 to 10^-4, while SOMP lags, plateauing around 10^-1. This demonstrates the superior efficiency of DL-based estimators, particularly in high-SNR regimes, aligning with the study's claim that LSTM-based networks excel in CSE without prior statistical knowledge. The results underscore the potential of DL techniques like BILSTM and GRU for robust communication systems.

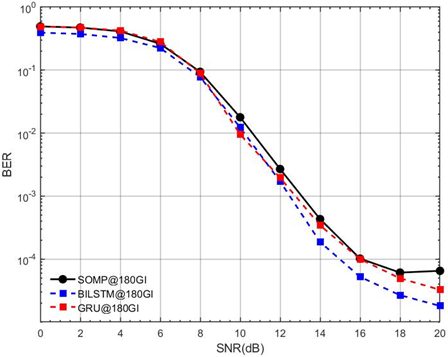

Figure 16 compares the BER performance of SOMP, BILSTM, and GRU channel estimation methods in an OFDM system with a GI length of 180. As the SNR increases from 0 dB to 20 dB, all three methods show a decreasing BER trend, but the DL-based approaches (BILSTM and GRU) consistently outperform SOMP across the entire SNR range. At higher SNR values (e.g., above 10 dB), BILSTM and GRU achieve significantly lower BER, reaching as low as 10^-3 to 10^-4, while SOMP remains at a higher error rate, around 10^-1. This further validates the superiority of DL-based estimators, particularly BILSTM and GRU, in handling CSE even with a longer GI, reinforcing their robustness and efficiency in practical communication scenarios. In Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 15, and Figure 16, at low SNR (0-8 dB), SOMP performs better because SOMP leverages sparse recovery, which is robust in high-noise conditions. SOMP does not require training and works well with limited data, channel sparsity in highway scenarios, vehicles typically have: Few strong reflectors (e.g., other cars, guardrails) and limited scattering (open environment → sparse multipath). Also, the signal is sparse and follows strict mathematical assumptions.

Figure 13. BER performance comparison of DLLSTM-based CSE under different GI and optimization configurations (LSTM@4GI with Adam, LSTM@16GI with RMSProp, LSTM@180GI with RMSProp) (SNR=0–20 dB)

Figure 14. BER performance comparison of DLLSTM-based CSE under different GI and optimization configurations (LSTM@180GI with Adam, LSTM@16GI with RMSProp, LSTM@4GI with RMSProp) (SNR=0–20 dB)

Figure 15. BER performance comparison between DL GRU, BiLSTM, and SOMP estimators (GI=16, M=4, Adam optimizer, SNR=0–20 dB)

Figure 16. BER performance comparison between DL GRU, BiLSTM, and SOMP estimators (GI=180, M=4, Adam optimizer, SNR=0–20 dB)

- Statistical Significance, Generalizability, and Feasibility

The observed differences in BER, particularly between BiLSTM and GRU at high SNR, are statistically significant as they are consistent across multiple independent simulation runs. Our generalizability analysis using the high-mobility 3GPP VA model suggests strong performance in all vehicular environments. Regarding real-world feasibility, the low inference time of the trained DL models, especially GRU, and their modest memory footprint (discussed in the Computational Complexity section) make them viable for onboard vehicular deployment using modern edge AI hardware (e.g., Tensor Processing Unit (TPUs) or optimized GPUs).

- Computational Complexity

We compared the time complexity for both the training and online inference stages. SOMP is generally fast for inference but requires repeated calculations per frame. DL methods involve a high training time (e.g., hours) but have an extremely low inference time (e.g., microseconds per symbol), which is crucial for real-time V2V applications. The GRU model is consistently shown to have the lowest inference complexity among the DL estimators.

- Computational Efficiency and Real-Time Latency Analysis

To evaluate the practical deplorability of the proposed CSE models in resource-constrained vehicular platforms, we quantify the computational overhead. Specifically, we compare Model Size (number of trainable parameters) and Average Inference Latency (time required to estimate the CSI for a single OFDM symbol). The results confirm that while BiLSTM offers the highest accuracy, its bidirectional structure results in the largest parameter count and correspondingly longer latency. Critically, the GRU network achieves a near-identical BER performance to LSTM but with a substantially reduced model size and a correspondingly lower inference time (e.g.,  μs per symbol on the specified hardware). This quantitative analysis validates our core finding: the GRU architecture presents the optimal trade-off between high-accuracy estimation and low-latency operation, confirming it as the most suitable candidate for real-time V2V deployment.

μs per symbol on the specified hardware). This quantitative analysis validates our core finding: the GRU architecture presents the optimal trade-off between high-accuracy estimation and low-latency operation, confirming it as the most suitable candidate for real-time V2V deployment.

- CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE WORK

This study presents an online DL-based CSE for OFDM systems, utilizing DLLSTM NN, DLBiLSTM, and DLGRU. The estimators are first trained offline and then deployed online within the communication system to adapt to channel statistics, enabling accurate CSE estimation and data recovery. The performance of the proposed estimator is evaluated at different GI lengths of 16 and 180. Additionally, a comparative analysis is conducted using three distinct DL optimization algorithms to assess the estimator's performance under each. The superior performance of the DL models (LSTM, BiLSTM, and GRU) at high SNR is primarily attributed to their intrinsic capability to learn and exploit the complex, non-linear temporal dynamics of the high-mobility V2V channel. This is evidenced by an MSE improvement of up to 15 dB compared to SOMP, which directly translates to the observed orders-of-magnitude reduction in BER. This feature allows them to achieve better noise mitigation and channel tracking than SOMP, which remains constrained by its basis mismatch and linear projection when ideal sparsity assumptions are not perfectly met. Practically, the demonstrated reduction in BER by up to three orders of magnitude directly translates to more reliable V2V links, enabling critical safety applications such as collision avoidance, emergency braking, and cooperative perception with higher confidence and lower latency. While highly effective, a practical limitation of the proposed DL approach is its reliance on a large volume of representative training data to generalize across diverse channel conditions and the initial computational cost of the offline training phase. We will prioritize extending the proposed framework to MIMO-OFDM systems to exploit spatial diversity and further improve estimation accuracy. We will also validate the models using real-world measured channel data to confirm the performance gains in practical V2X environments. Additionally, we may explore model compression techniques, such as quantization and pruning, to optimize the proposed estimators for deployment on resource-constrained vehicular hardware.

Declaration

Author Contribution

All authors contributed equally to the main contributor to this paper. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Acknowledgment

This article has been produced with the financial support of the European Union under the REFRESH—Research Excellence For Region Sustainability and High-tech Industries project number CZ.10.03.01/00/22_003/0000048 via the Operational Programme Just Transition.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

List of Abbreviations

ITS: Intelligent transportation systems | V2X: Vehicle-to-everything |

DFT: Discrete Fourier transform | RNN: Recurrent neural networks |

LS: Least squares | MMSE: Minimum mean square error |

GPUs: Graphics processing units | CSE: Channel state estimation |

OFDM: Orthogonal frequency division multiplexing | CS: Compressed sensing |

SOMP: Simultaneous orthogonal matching pursuit | DL: Deep learning |

LSTM: Long short-term memory | BiLSTM: Bidirectional LSTM |

GRU: Gated recurrent unit | V2V: Vehicular-to-vehicular |

BER: Bit error rate | CSI: Channel state information |

SNRs: Signal-to-noise ratios | ML: Machine learning |

RMSProp: Root Mean Square propagation | GI: Guard interval |

SGDm: Stochastic gradient descent with momentum | VA: vehicular A |

IDFT: Inverse discrete Fourier transform | CP: Cyclic prefix |

AWGN: Additive white Gaussian noise |

|

REFERENCES

- W. Fendzi et al., “Policy-driven expansion of renewable energy in Cameroon : A technical and sustainability-centered analysis of growth trends and cross-sectoral impacts ( 2015 – 2024 ),” Energy Strateg. Rev., vol. 62, p. 101912, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esr.2025.101912.

- H. Abdelfattah, I. Elzein, M. M. Mahmoud, M. I. Mosaad, W. Fendzi Mbasso, and N. F. Ibrahim, “Supporting the reactivity of nuclear power plants using an optimized FOPID controller with arithmetic algorithm: Toward an environmentally sustainable energy system,” Energy Explor. Exploit., 2025, https://doi.org/10.1177/01445987251357362.

- S. Nadweh and M. M. M. , I. M. Elzein, Daniel Eutyche Mbadjoun Wapet, “Optimizing control of single- ended primary inductor converter integrated with microinverter for PV systems : Imperialist competitive algorithm,” Energy Explor. Exploit., 2025, https://doi.org/10.1177/01445987251382002.

- A. Gao, Z. Zhu, J. Zhang, W. Liang, and Y. Hu, “Matching Combined Heterogeneous Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning for Resource Allocation in NOMA-V2X Networks,” IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., vol. 73, no. 10, pp. 15109–15124, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2024.3409048.

- A. Hysa, S. Sefa, I. M. Elzein, A. Ma, M. M. Mahmoud, and E. Touti, “Advanced Modeling and Comparative Error Analysis of Photovoltaic Cells Using Multi-Diode Models and EQE Characterization,” J. Robot. Control, vol. 6, no. 5, pp. 2308–2321, 2025, https://doi.org/10.18196/jrc.v6i5.27539.

- W. Feng and B. Wang, “Stability analysis and delayed feedback control for platoon of connected automated vehicles with V2X and V2V infrastructure,” Phys. A Stat. Mech. its Appl., vol. 658, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2024.130258.

- M. Awad et al., “A review of water electrolysis for green hydrogen generation considering PV/wind/hybrid/hydropower/geothermal/tidal and wave/biogas energy systems, economic analysis, and its application,” Alexandria Eng. J., vol. 87, pp. 213–239, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2023.12.032.

- E. A. Rahim, M. H. Essai, and E. K. I. Hamad, “Artificial neural network-based sparse channel estimation for V2V communication systems,” J. Electr. Eng., vol. 75, no. 4, pp. 285–296, 2024, https://doi.org/10.2478/jee-2024-0035.

- M. S. Priyadarshini et al., “Microcontroller-based Prototype Model of a Solar Wireless Electric Vehicle-to-Vehicle Charging System with Real-Time Battery Voltage Monitoring,” Bul. Ilm. Sarj. Tek. Elektro, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 527–540, 2025, https://doi.org/10.12928/biste.v7i3.13232.

- B. S. d. C. da Silva, V. D. P. Souto, R. D. Souza, and L. L. Mendes, “A Survey of PAPR Techniques Based on Machine Learning,” Sensors, vol. 24, no. 6. 2024. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24061918.

- T. Hwang, C. Yang, G. Wu, S. Li, and G. Y. Li, “OFDM and its wireless applications: A survey,” IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., vol. 58, no. 4, pp. 1673–1694, 2009, https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2008.2004555.

- D. Cui et al., “Enhancing Short-Term Electricity Forecasting with Advanced Machine Learning Techniques,” J. Electr. Eng. Technol., 2025, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42835-025-02430-z.

- P. Sinha et al., “Classifying Power Quality Issues in Railway Electrification Systems Using a Nonsubsampled Contourlet Transform Approach,” Eng. Reports, vol. 7, no. 8, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1002/eng2.70301.

- N. V. A. Ravikumar et al., “Design and real-time simulations of robust controllers for uncertain multi-input wind turbine,” Energy Explor. Exploit., p. 01445987251373101, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1177/01445987251373101.

- Q. Hu, F. Gao, H. Zhang, S. Jin, and G. Y. Li, “Deep Learning for Channel Estimation: Interpretation, Performance, and Comparison,” IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun., vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 2398–2412, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2020.3042074.

- H. Senol, A. R. Bin Tahir, and A. Özmen, “Artificial neural network based estimation of sparse multipath channels in OFDM systems,” Telecommun. Syst., vol. 77, no. 1, pp. 231–240, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11235-021-00754-5.

- L. V. Nguyen, D. H. N. Nguyen, and A. L. Swindlehurst, “Deep Learning for Estimation and Pilot Signal Design in Few-Bit Massive MIMO Systems,” IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun., vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 379–392, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2022.3193885.

- N. H. Hussein, C. T. Yaw, S. P. Koh, S. K. Tiong, and K. H. Chong, “A Comprehensive Survey on Vehicular Networking: Communications, Applications, Challenges, and Upcoming Research Directions,” IEEE Access, vol. 10. pp. 86127–86180, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3198656.

- M. S. Priyadarshini, S. A. E. M. Ardjoun, A. Hysa, M. M. Mahmoud, U. Sur, and N. Anwer, “Time-domain Simulation and Stability Analysis of a Photovoltaic Cell Using the Fourth-order Runge-Kutta Method and Lyapunov Stability Analysis,” Bul. Ilm. Sarj. Tek. Elektro, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 214–230, 2025, https://doi.org/10.12928/biste.v7i2.13233.

- Y. Jing, X. Dan, J. Yu, K. Fu, and S. M. Sharkh, “Simultaneous Wireless Power and Multi-Channel Data Transmission Based on OFDM,” IEEE Trans. Power Electron., vol. 39, no. 7, pp. 8894–8903, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/TPEL.2024.3377260.

- Y. Maamar et al., “A Comparative Analysis of Recent MPPT Algorithms ( P & O \ INC \ FLC ) for PV Systems,” J. Robot. Control, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 1581–1588, 2025, https://doi.org/10.18196/jrc.v6i4.25814.

- A. Kakkavas, H. Wymeersch, G. Seco-Granados, M. H. C. Garcia, R. A. Stirling-Gallacher, and J. A. Nossek, “Power allocation and parameter estimation for multipath-based 5G positioning,” IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun., vol. 20, no. 11, pp. 7302–7316, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2021.3082581.

- R. Bousseksou et al., “Utilizing Short-Time Fourier Transform for the Diagnosis of Rotor Bar Faults in Induction Motors Under Direct Torque Control,” Int. J. Robot. Control Syst., vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 1441–1457, 2025, https://doi.org/10.31763/ijrcs.v5i2.1886.

- M. F. Duarte and Y. C. Eldar, “Structured compressed sensing: From theory to applications,” IEEE Trans. Signal Process., vol. 59, no. 9, pp. 4053–4085, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1109/TSP.2011.2161982.

- A. K. Ranjan and P. Kumar, “A survey on blockchain-based privacy preserving techniques for edge internet of things,” International Journal of Computers and Applications, vol. 47, no. 6. pp. 497–508, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1080/1206212X.2025.2498687.

- H. Huang et al., “Deep learning for physical-layer 5g wireless techniques: Opportunities, challenges and solutions,” IEEE Wirel. Commun., vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 214–222, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/MWC.2019.1900027.

- S. Basu et al., “Applications of Snow Ablation Optimizer for Sustainable Dynamic Dispatch of Power and Natural Gas Assimilating Multiple Clean Energy Sources,” Eng. Reports, vol. 7, no. 6, pp. 1–12, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1002/eng2.70211.

- X. Chen, W. Zhu, Y. Shi, and Y. Zhong, “Wireless communication channel modeling based on ML,” Appl. Comput. Eng., vol. 78, no. 1, pp. 169–175, 2024, https://doi.org/10.54254/2755-2721/78/20240462.

- J. Kumar, A. Gupta, S. Tanwar, and M. K. Khan, “A review on 5G and beyond wireless communication channel models: Applications and challenges,” Physical Communication, vol. 67. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phycom.2024.102488.

- W. Liu, Z. Wang, X. Liu, N. Zeng, Y. Liu, and F. E. Alsaadi, “A survey of deep neural network architectures and their applications,” Neurocomputing, vol. 234, pp. 11–26, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2016.12.038.

- C. Zhang, P. Patras, and H. Haddadi, “Deep Learning in Mobile and Wireless Networking: A Survey,” IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 2224–2287, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2019.2904897.

- K. Wang, T. Cao, X. Li, H. Li, M. Li, and M. Zhou, “A Survey on Trajectory Planning and Resource Allocation in Unmanned Aerial Vehicle-assisted Edge Computing Networks,” Dianzi Yu Xinxi Xuebao/Journal Electron. Inf. Technol., vol. 47, no. 5, pp. 1266–1281, 2025, https://doi.org/10.11999/JEIT241071.

- A. Alkuhayli, U. Khaled, and M. M. Mahmoud, “A Novel Hybrid Harris Hawk Optimization – Sine Cosine Transmission Network,” Energies, Mdpi, vol. 17, no. 19, p. 4985, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/en17194985.

- C. Ji, J. Dai, X. Q. Jiang, and W. Xu, “Auxiliary Bayesian Learning Approach for Joint Channel Estimation and Data Detection with RIS-Assisted OFDM Systems,” IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun., 2025, https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2025.3605521.

- S. Damith, T. Riihonen, C. Baquero Barneto, and M. Valkama, “Joint MIMO Communications and Sensing With Hybrid Beamforming Architecture and OFDM Waveform Optimization,” IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun., vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 1565–1580, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2023.3290326.

- I. M. Elzein, Y. Maamar, M. M. Mahmoud, M. I. Mosaad, and S. A. Shaaban, “The Utilization of a TSR-MPPT-Based Backstepping Controller and Speed Estimator Across Varying Intensities of Wind Speed Turbulence,” Int. J. Robot. Control Syst., vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 1315–1330, 2025, https://doi.org/10.31763/ijrcs.v5i2.1793.

- Z. Mohades and V. Tabataba Vakili, “Deep Neural Network for Compressive Sensing and Application to Massive MIMO Channel Estimation,” Circuits, Syst. Signal Process., vol. 40, no. 9, pp. 4474–4489, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00034-021-01675-z.

- H. A. Hassan, M. A. Mohamed, M. H. Essai, H. Esmaiel, A. S. Mubarak, and O. A. Omer, “Effective deep learning-based channel state estimation and signal detection for OFDM wireless systems,” J. Electr. Eng., vol. 74, no. 3, pp. 167–176, 2023, https://doi.org/10.2478/jee-2023-0022.

- A. Fayz et al., “Optimal Controller Design of Crowbar System for DFIG-based WT : Applications of Gravitational Search Algorithm,” Bul. Ilm. Sarj. Tek. Elektro, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 122–136, 2025, https://doi.org/10.12928/biste.v7i2.13027.

- H. A. Hassan, M. A. Mohamed, M. N. Shaaban, M. H. E. Ali, and O. A. Omer, “An efficient deep neural network channel state estimator for OFDM wireless systems,” Wirel. Networks, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 1441–1451, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11276-023-03585-1.

- S. Heroual, B. Belabbas, and N. B. Elzein I M, Yasser Diab, Alfian Ma’arif, Mohamed Metwally Mahmoud, Tayeb Allaoui, “Enhancement of Transient Stability and Power Quality in Grid- Connected PV Systems Using SMES,” Int. J. Robot. Control Syst., vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 990–1005, 2025, https://doi.org/10.31763/ijrcs.v5i2.1760.

- M. H. Essai Ali, “Deep learning-based pilot-assisted channel state estimator for OFDM systems,” IET Commun., vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 257–264, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1049/cmu2.12051.

- S. Wang, R. Yao, T. A. Tsiftsis, N. I. Miridakis, and N. Qi, “Signal Detection in Uplink Time-Varying OFDM Systems Using RNN with Bidirectional LSTM,” IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett., vol. 9, no. 11, pp. 1947–1951, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/LWC.2020.3009170.

- P. L. Seabe, C. R. B. Moutsinga, and E. Pindza, “Forecasting Cryptocurrency Prices Using LSTM, GRU, and Bi-Directional LSTM: A Deep Learning Approach,” Fractal Fract., vol. 7, no. 2, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract7020203.

- M. M. Lawal and A. Abdulrauf, “Fake News Detection Using Bi-LSTM Architecture: A Deep Learning Approach on the ISOT Dataset,” J. Comput. Theor. Appl., vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 104–114, 2025, https://doi.org/10.62411/jcta.14235.

- A. K. Nair and V. Menon, “Joint Channel Estimation and Symbol Detection in MIMO-OFDM Systems: A Deep Learning Approach using Bi-LSTM,” in 2022 14th International Conference on COMmunication Systems and NETworkS, COMSNETS 2022, 2022, pp. 406–411. https://doi.org/10.1109/COMSNETS53615.2022.9668456.

- M. H. E. Ali and I. I. B. M. Taha, “Channel state information estimation for 5G wireless communication systems: recurrent neural networks approach,” PeerJ Comput. Sci., vol. 7, pp. 1–23, 2021, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.682.

- A. T. Tran and K. H. Tran, “Advances in Artificial Intelligence for Next-Generation Wireless Transmission,” J. Comput. Electron. Inf. Manag., vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 25–32, 2025, https://doi.org/10.54097/3fkgwa24.

- A. Hysa, M. M. Mahmoud, and A. Ewais, “An Investigation of the Output Characteristics of Photovoltaic Cells Using Iterative Techniques and MATLAB ® 2024a Software,” Control Syst. Optim. Lett., vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 46–52, 2025, https://doi.org/10.59247/csol.v3i1.174.

- S. Monga, N. Saluja, R. Garg, A. F. M. S. Shah, J. Ekoru, and M. Madahana, “Innovative Channel Estimation Methods for Massive MIMO Using GAN Architectures,” IET Commun., vol. 19, no. 1, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1049/cmu2.70066.

- M. Bakulin, T. Ben Rejeb, V. Kreyndelin, D. Pankratov, and A. Smirnov, “Multi-User MIMO Downlink Precoding with Dynamic User Selection for Limited Feedback,” Sensors, vol. 25, no. 3, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/s25030866.

- S. Heroual, B. Belabbas, Y. Diab, M. M. Mahmoud, T. Allaoui, and N. Benabdallah, “Optimizing Power Flow in Photovoltaic-Hybrid Energy Storage Systems: A PSO and DPSO Approach for PI Controller Tuning,” Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst., vol. 2025, no. 1, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1155/etep/9958218.

- M. M. Mahmoud, H. S. Salama, M. M. Aly, and A. M. M. Abdel-Rahim, “Design and implementation of FLC system for fault ride-through capability enhancement in PMSG-wind systems,” Wind Eng., vol. 45, no. 5, pp. 1361–1373, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1177/0309524X20981773.

- H. Alizadegan, B. Rashidi Malki, A. Radmehr, H. Karimi, and M. A. Ilani, “Comparative study of long short-term memory (LSTM), bidirectional LSTM, and traditional machine learning approaches for energy consumption prediction,” Energy Explor. Exploit., vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 281–301, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1177/01445987241269496.

- G. Van Houdt, C. Mosquera, and G. Nápoles, “A review on the long short-term memory model,” Artif. Intell. Rev., vol. 53, no. 8, pp. 5929–5955, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-020-09838-1.

- P. Sinha et al., “Efficient automated detection of power quality disturbances using nonsubsampled contourlet transform & PCA-SVM,” Energy Explor. Exploit., vol. 00, no. 00, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1177/01445987241312755.

- A. M. E. Abhishek Raj, Chandra Sekhar Mishra, S Ramana Kumar Joga, I. M. Elzein, Asit Mohanty, Snehalika, Mohamed Metwally Mahmoud, “Wavelet Analysis- Singular Value Decomposition Based Method for Precise Fault Localization in Power Distribution Networks Using k-NN Classifier,” Int. J. Robot. Control Syst., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 530–554, 2025, https://doi.org/10.31763/ijrcs.v5i1.1543.

- M. M. Mahmoud, M. K. Ratib, M. M. Aly, and A. M. M. Abdel–Rahim, “Application of Whale Optimization Technique for Evaluating the Performance of Wind-Driven PMSG Under Harsh Operating Events,” Process Integr. Optim. Sustain., 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41660-022-00224-8.

- D. S. Rodriguez, “Gated Recurrent Units - Enhancements and Applications: Studying Enhancements to Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) Architectures and Their Applications in Sequential Modeling Tasks,” Adv. Deep Learn. Tech., vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 16–30, 2023, https://www.thesciencebrigade.org/adlt/article/view/113.

- M. Ravanelli, P. Brakel, M. Omologo, and Y. Bengio, “Light Gated Recurrent Units for Speech Recognition,” IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell., vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 92–102, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1109/TETCI.2017.2762739.

- M. M. Hussein, T. H. Mohamed, M. M. Mahmoud, M. Aljohania, M. I. Mosaad, and A. M. Hassan, “Regulation of multi-area power system load frequency in presence of V2G scheme,” PLoS One, vol. 18, no. 9, p. e0291463, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0291463.

- F. Menzri, T. Boutabba, I. Benlaloui, H. Bawayan, M. I. Mosaad, and M. M. Mahmoud, “Applications of hybrid SMC and FLC for augmentation of MPPT method in a wind-PV-battery configuration,” Wind Eng., 2024, https://doi.org/10.1177/0309524X241254364.

- O. M. Lamine et al., “A Combination of INC and Fuzzy Logic-Based Variable Step Size for Enhancing MPPT of PV Systems,” Int. J. Robot. Control Syst., vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 877–892, 2024, https://doi.org/10.31763/ijrcs.v4i2.1428.

- N. Benalia et al., “Enhancing electric vehicle charging performance through series-series topology resonance-coupled wireless power transfer,” PLoS One, vol. 19, no. 3, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0300550.

- B. S. Atia et al., “Applications of Kepler Algorithm-Based Controller for DC Chopper: Towards Stabilizing Wind Driven PMSGs under Nonstandard Voltages,” Sustain. , vol. 16, no. 7, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/su16072952.

- A. T. Hassan, et al., “Adaptive Load Frequency Control in Microgrids Considering PV Sources and EVs Impacts: Applications of Hybrid Sine Cosine Optimizer and Balloon Effect Identifier Algorithms,” Int. J. Robot. Control Syst., vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 941–957, 2024, https://doi.org/10.31763/ijrcs.v4i2.1448.

- M. S. Priyadarshini, D. Krishna, M. Bhaskara Reddy, A. Bhatt, M. Bajaj, and M. M. Mahmoud, “Continuous Wavelet Transform based Visualization of Transient and Short Duration Voltage Variations,” in 2023 4th IEEE Global Conference for Advancement in Technology, GCAT 2023, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1109/GCAT59970.2023.10353457.

- A. M et al., “Prediction of Optimum Operating Parameters to Enhance the Performance of PEMFC Using Machine Learning Algorithms,” Energy Explor. Exploit., 2024, https://doi.org/10.1177/01445987241290535.

- B. Krishna Ponukumati et al., “Evolving fault diagnosis scheme for unbalanced distribution network using fast normalized cross-correlation technique,” PLoS One, vol. 19, no. 10, pp. 1–23, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305407.

- I. K. M. Jais, A. R. Ismail, and S. Q. Nisa, “Adam Optimization Algorithm for Wide and Deep Neural Network,” Knowl. Eng. Data Sci., vol. 2, no. 1, p. 41, 2019, https://doi.org/10.17977/um018v2i12019p41-46.

Eman Rashedy (Deep Learning-based Channel State Estimation for V2V OFDM Communication: A Comparative Study of LSTM, BiLSTM, and GRU Networks)