ISSN: 2685-9572 Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro

Vol. 7, No. 3, September 2025, pp. 434-449

A Generalized Deep Learning Approach for Multi Braille Character (MBC) Recognition

Made Ayu Dusea Widyadara 1, Anik Nur Handayani 2, Heru Wahyu Herwanto 3, Tony Yu 4

1,2,3 Department of Electrical Engineering and Informatics, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Negeri Malang, Malang, East Java, Indonesia

4 Electrical and computer engineering, Rice University, Houston, Texas, United States

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 06 June 2025 Revised 24 July 2025 Accepted 21 August 2025 |

|

Automated visual recognition of Multi Braille Characters (MBC) poses significant challenges for assistive reading technologies for the visually impaired. The intricate dot configurations and compact layouts of Braille complicate MBC classification. This study introduces a deep learning approach utilizing Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and compares four leading architectures: ResNet-50, ResNet-101, MobileNetV2, and VGG-16. A dataset comprising 105 MBC classes was developed from printed Braille materials and underwent preprocessing that included image cropping, brightness enhancement, character position labeling, and resizing to 89×89 pixels. A 70:20:10 data partitioning strategy was applied for training and evaluation, with variations in batch sizes (8–128) and epochs (50–500). The results demonstrate that ResNet-101 achieved superior performance, attaining an accuracy of 91.46%, an F1-score of 89.48%, and a minimum error rate of 8.5%. ResNet-50 and MobileNetV2 performed competitively under specific conditions, whereas VGG-16 consistently exhibited lower accuracy and training stability. Standard deviation assessments corroborated the stability of residual architectures throughout the training process. These results endorse ResNet-101 as the most effective architecture for Multi Braille Character classification, highlighting its potential for incorporation into automated Braille reading systems, a tool for translating braille into text or sound for future needs. |

Keywords: Braille Recognition; Convolutional Neural Network (CNN); Comparing Architectures; Multi Braille Character Classification; Assistive Technology |

Corresponding Author: Anik Nur Handayani, Department of Electrical Engineering and Informatics, Faculty of Engineering,Universitas Negeri Malang, Malang, East Java, Indonesia. Email: anik.nur.ft@um.ac.id |

This work is open access under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: M. A. D. Widyadara, A. N. Handayani, H. W. Herwanto, and T. Yu, “A Generalized Deep Learning Approach for Multi Braille Character (MBC) Recognition,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 434-449, 2025, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v7i3.13891. |

INTRODUCTION

Braille is a means of communication and a valuable source of information for individuals who are visually impaired or blind [1][2]. The Braille system utilizes a conventional pattern recognition approach, whereby each character is distinguished by a configuration of raised dots in a six-dot matrix arranged in three rows and two columns [3][4]. The creation of Braille characters, alphabets and symbol codes requires the combination of these dots, thereby facilitating the transcription of textual information in a tactile format [5]. The development of effective communication and information exchange between individuals with and without visual impairments would be significantly enhanced if there were a universal understanding of braille among the former, reducing reliance on Braille literacy among sighted individuals. The process of acquiring proficiency in braille is a protracted one, necessitating a prolonged period of training to develop the ability to interpret Braille dots as a means of deciphering information [6][7]. To expedite braille learning and improve communication across visual impairments, an effective translation system for braille is essential. This system eliminates the lengthy duration typically associated with traditional braille learning methods.

Automated Braille recognition systems hold the potential to connect this divide, with CNNs rising as an exciting answer because of their exceptional ability to identify patterns. The use of CNN for multi-character Braille recognition can significantly improve detection accuracy and speed, facilitating communication between people with visual impairments and the general public. To determine the most effective CNN architecture for Braille detection, it is necessary to compare the various types available [8]. The CNN architecture that is selected for implementation should take into consideration the number of convolutional layers, the kernel size, and the data augmentation techniques in order to enhance the model's performance [9]. Architectures such as ResNet and VGGNet have been shown to be effective for various image recognition tasks, including the recognition of Braille patterns [10][11]. There exists groundbreaking research unveiling an innovative image-free sensing method that empowers the recognition of multiple targets by harnessing a convolutional recurrent neural network (CRNN) featuring a bidirectional LSTM design, facilitating the concurrent prediction of various characters without necessitating image reconstruction, a crucial factor for uses like Braille reading [12]. This strategy transcends the constraints of single-character models, which falter in tasks requiring continuous reading, thereby offering a remedy for the identification of multi-Braille character (MBC) in practical scenarios. The objective of this research project is to explore and compare four convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures for detecting multi-Braille characters (MBC), whereas previous studies have focused on single Braille characters. The primary objective of this research endeavour is to ascertain the most efficient and accurate model. The model has been developed for the purpose of detecting Braille syllables in Indonesian. The capacity to discern multi-Braille characters (MBC) is anticipated to facilitate the development of a Braille translation system that demonstrates precise accuracy and rapid operational efficiency.

- LITERATURE REVIEW

The use of pattern recognition technology in Braille systems is imperative to enhance the accessibility of information for visually impaired individuals, thereby facilitating more effective communication [1],[10][11]. It is evident that these technologies can encompass methods such as Optical Braille Recognition (OBR), which is designed to translate Braille letters into a language that is more accessible and comprehensible [13]. Achieving a high accuracy value is possible by converting RGB images into grayscale and establishing pattern recognition techniques with CNN [14]. Converting braille detection results into audio constitutes a solution to accelerate the interpretation of such results, benefitting both blind and non-blind individuals [15][16]. Syllable-based detection has been demonstrated to facilitate accelerated learning, thereby enabling users to expeditiously comprehend (Table 1) and utilize the detection system [17].

Table 1. Previous research on braille character recognition with CNN

Reference | Clasification Model |

[1] | VGG16, ResNet50, Inceptionv3, dan DenseNet201 |

[5] | ResNet-50 |

[13] | Base CNN, VGG-16, ResNet50, and Inception-v3 |

[16] | Modified custom CNN model |

[18] | LeNet-5 |

[19] | DCNN |

[20] | VGG-16 |

[21] | VGG-16 BC-CNN |

[22] | Faster r-CNN-FPN-ResNet-50 |

[23] | ResNet-18, ResNet-34, and ResNet-50 |

Deep neural networks (DNNs) enable automated feature extraction via layered training. The training process is characterized by incremental and hierarchical methodologies. Specifically, each layer undergoes independent training to identify progressively intricate feature representations at varying depths within the network [24][25]. The features generated by one layer are passed on to the next, forming a cascading structure that captures the full characteristics of the data without requiring specialized user intervention or knowledge [1]. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are a prominent type of deep neural networks (DNNs), and they have demonstrated remarkable proficiency in various applications within the domain of computer vision [26], [27]. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have been shown to enhance performance in a range of applications, including visual pattern recognition, medical image analysis, image classification and segmentation, object detection, and natural language processing [1],[26]. The aforementioned benefits render CNN a significantly relevant architecture in the development of intelligent systems that are visually based, including in Braille recognition [28]. Despite the fact that earlier research has concentrated on individual Braille characters, the recognition of multi-Braille characters remains an area that requires further investigation, particularly in the context of languages such as Indonesian.

- METHODS

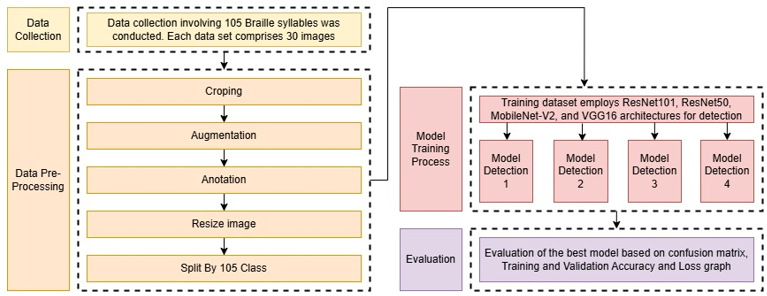

This section delineates the rigorous methodology utilized in this research. The methodology includes data collection, pre-processing, model training, and evaluation. These processes are depicted in Figure 1. The methodology comprises essential steps in data processing, modeling, and performance assessment. The following steps aim to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the model in classifying multi-Braille characters (MBC). The subsequent section provides a concise overview of each stage in the methodology.

Figure 1. Research methodology

Data Collection

The importance of data collection in this study, which focuses on the classification of multi-Braille characters using image processing techniques, is crucial. Figure 2 illustrates the basic structure of Braille characters, which serve as the foundational unit for Multi Braille Character (MBC) recognition. The dot matrix Figure 2(a) shows the 6-dot layout used to encode each Braille character in a 2-column by 3-row configuration. Figure 2(b) displays a single character (‘b’), while Figure 2(c) demonstrates the representation of multiple Braille characters in sequence (‘ba’ and ‘bi’). This visual structure is crucial for data preprocessing methods. Grasping this configuration facilitates precise Braille cell detection and aids in CNN training labeling.

Figure 2. The following braille characters are presented: the dot matrix (a), the letter ‘b’ single character (b), the letter ‘b’ and ‘a’ for multi braille character (c)

The dataset includes 105 MBC classes, featuring diverse vowel and consonant pairings. Data was obtained from manually curated Braille publications. A 108 MP camera with specific sensor attributes ensured optimal accuracy in recognizing raised Braille dots. The camera operated at a resolution of 12000 × 9000 pixels and an aperture of f/1.8 to optimize lighting and depth of field. High-quality RGB images were captured in JPEG format with an 8-bit color depth. Image acquisition was performed at a distance of 30 centimeters from the Braille sheet to maintain consistency and precision. The lighting system consisted of three 10-watt LED lights positioned at a 45° angle to the Braille sheet. This arrangement reduces noise and ensures uniform light dissemination. The setup further minimizes reflections and accentuates the raised Braille dots, aiding in image processing. It also seeks to produce subtle shadows on dot protrusions, thereby improving contrast with the background. Our pipeline produced high-quality images, which is more conducive to the extraction and training of features in machine learning models. This provides a robust foundation for the development of an effective Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model for the classification of Multi Braille Character (MBC).

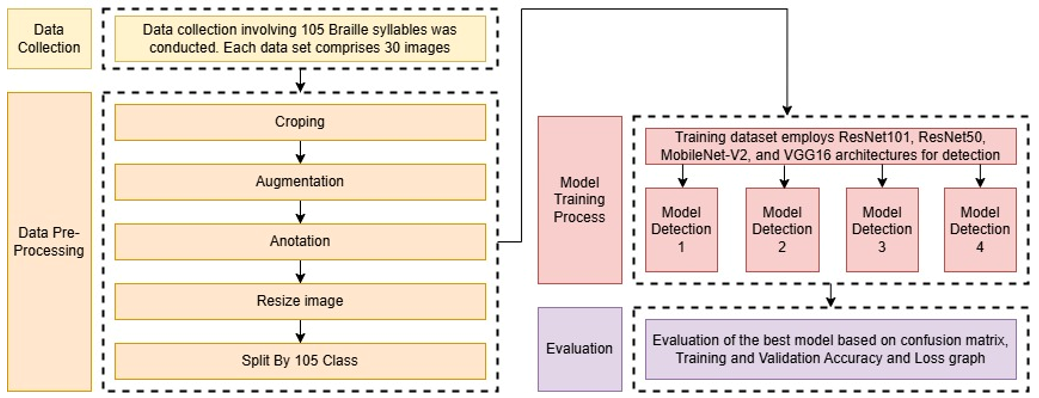

Data Preprocessing

The acquired image data will be pre-processed to enhance processing efficacy can be seen in Figure 3. The first step is segmenting the Braille dataset into characters of two dots by three dots. A direct extraction method is utilized for multi-Braille characters, bypassing threshold setting. Contour detection techniques are applied on grayscale images or edge detection outputs to identify object boundaries. These detected areas may correspond to two Braille characters. Upon successful contour detection, each contour is evaluated iteratively for size and position. The MBC organizes uniform bounding boxes for cutting, linking similar character shapes. Bounding box sizes come from the average of two Braille characters in an image. This box fits within a grid structure, based on predetermined positions and intervals. To speed up annotation, each cropped image receives a class label tied to its MBC. The annotation records bounding box details, including position and size, in text or JSON formats for CNN training. Each annotation uniquely marks the MBC's position and class in the image. Labeling involves 105 MBC classes (ba,bi,bu etc.) Before feeding the images into the CNN, they are resized to meet the model's dimensions. The images are standardized to a uniform resolution, ensuring consistency in training. This resizing preserves the aspect ratio, keeping the MBC proportional. The preprocessing steps—cropping, annotating, and resizing—are vital for preparing the MBC dataset for effective CNN training.

Figure 3. Data Preprocessing Flow

Model Training Process

CNNs are inspired by the structure of biological neural networks in the human brain, and are part of deep neural networks that have been widely used in digital image processing due to their ability to form deep network architectures [29]. The primary merit of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) is their capacity to acquire features from datasets in a hierarchical fashion, commencing with fundamental attributes such as edges and textures and advancing to higher-order characteristics like object contours or intricate patterns [30]. This research explores four CNNs: ResNet-50, ResNet-101, MobileNet-V2, and VGG-16. These models shine in depth, efficiency, and feature extraction. ResNet-50 and ResNet-101 utilize residual blocks, with the latter diving deeper for intricate features. VGG-16’s 3x3 convolutions and uniform pooling ensure stability and ease. Meanwhile, MobileNetV2 focuses on efficiency with depthwise separable convolutions, perfect for limited resources [31]. These models were tested for their prowess in recognizing Braille syllabic images. Alternative models like Inception and DenseNet were left out for being too complex and resource-heavy. Inception's branching structure hinders tuning, making it a poor fit here. DenseNet excels in gradient flow but struggles with memory and complexity. EfficientNet and custom CNNs were sidelined to spotlight standard models that are easy to implement and replicate. Together, the chosen architectures provide a robust review of performance, efficiency, and practicality for Braille recognition systems can be seen in Table 2.

The modelling process begins with the collection of Braille image datasets, which are then processed through a series of pre-processing stages. The images are resized to fit the requirements of the model architecture used, and data augmentation is performed to improve the model’s generalisation ability against data variations. The dataset is then divided into three subsets: the training set, validation set, and testing set, with a division ratio of 70%, 20%, and 10%, respectively. During the training phase, the Adam optimiser was used with the categorical cross-entropy loss function, and an exploration of several parameter configurations was conducted, including the number of epochs (50, 100, 300, and 500), batch size (8, 16, 32, 64, and 128), and image size variations (34×34, 55×55, and 89×89). The purpose of these variations is to determine the most optimal hyperparameter configuration to improve model performance. In this exploration, Fibonacci numbers will shape image dimensions as hyperparameters. This enchanting sequence begins with 0 and 1, endlessly cycling: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, and beyond. Artists revere this proportion for its mathematical grace. Dividing Fibonacci numbers reveals the elusive golden ratio, uncovering beauty as the sequence unfolds [32]-[34]. The choice of an 89 x 89 image size stems from trials with Fibonacci numbers aligning with CNN architecture needs. After the training process is complete, the model is evaluated using test data to measure its generalisation ability and effectiveness in accurately recognising Braille word patterns.

Table 2. Evaluation Criteria of CNN Architectures for Multi Braille Character (MBC) Classification

Evaluation Criteria | ResNet-50 | ResNet-101 | MobileNetV2 | VGG-16 |

Utilizes residual connections | √ | √ | √ | X |

Efficient for resource-constrained devices | X | X | √ | X |

Capable of handling very deep networks (>100 layers) | X | √ | X | X |

Simple and easy to implement architecture | X | X | X | √ |

Uses depthwise separable convolutions | X | X | √ | X |

Proven stable in 300–500 training epochs | √ | √ | √ | X |

Suitable for assistive technology development | √ | √ | √ | X |

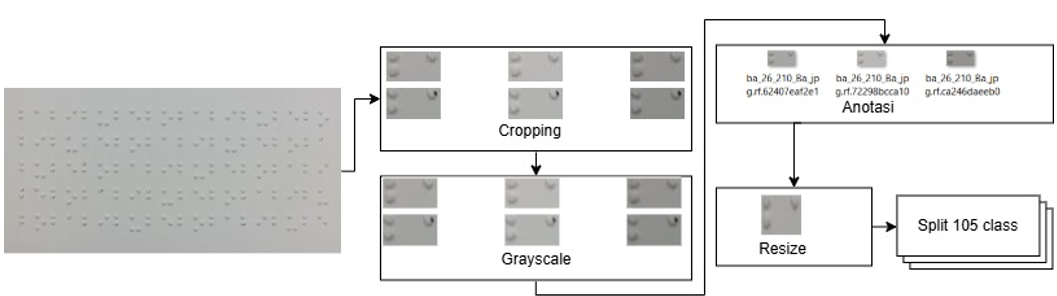

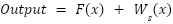

The classification paradigm utilizing Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) is typically segmented into two principal phases, namely feature learning and classification [35]. In the preliminary phase, the CNN architecture processes 89×89-pixel RGB images. Subsequently, feature learning employs convolutional and pooling techniques to extract significant visual features. This phase converts raw visual data into meaningful numerical representations. The generated outputs are then sent to the fully connected layer for image classification based on learned patterns. Subsequently, the model transitions to the fully connected layer. This phase is pivotal for synthesizing feature extraction outcomes for classification based on established MBC classifications. Figure 4 illustrates the development and operational workflow of this MBC classification model comprehensively.

Figure 4. CNN architecture model with ResNet-50

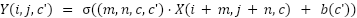

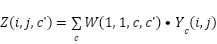

ResNet-50 utilises a bottleneck block consisting of a combination of 1×1, 3×3, and 1×1 convolution layers, where the first layer (1×1) is used to reduce the dimension (bottleneck), the second layer (3×3) for feature processing, and the third layer (1×1) to restore the dimension to its original size [36]. This approach significantly reduces the computational complexity compared to traditional architectures. Mathematically, the residual block processes the input x using the feature transformation F(x). This is then summed with the shortcut connection to produce the output:

|

| (1) |

In the event of a discrepancy between the dimensions of the input and output, the WS shortcut projection is utilised to effect the necessary adjustments, resulting in the following equation:

|

| (2) |

In this context, F(x) is comprised of a series of convolutional, normalization, and activation (ReLU) operations, whereas the shortcut connections enhance the efficiency of gradient propagation, mitigate the vanishing gradient issue, and facilitate the training of exceptionally deep networks. Through the implementation of these methodologies, ResNet-50 successfully attains superior performance in the domain of image classification while employing a more efficient parameter set compared to traditional models.

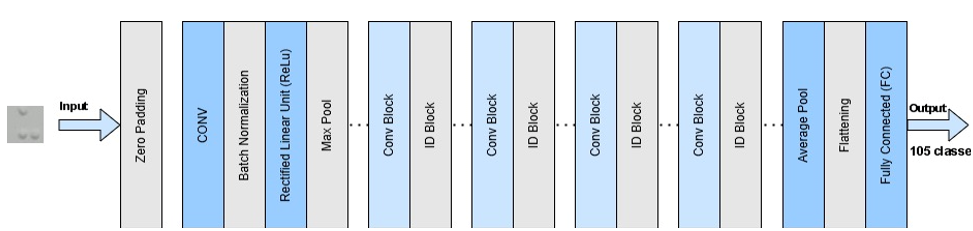

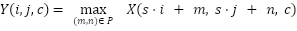

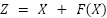

The ResNet-101 architecture illustrated in Figure 5, effectively mitigates the vanishing gradient issue in deep networks via shortcut connections. The input x is processed through a feature transformation F(x), which includes convolution, batch normalization, and ReLU activation. The output of this transformation is combined with the shortcut connection that carries original input information. To ensure dimensional consistency between input and output, a linear projection Ws is applied to the shortcut. The output of the residual block is mathematically represented as:

|

| (3) |

Figure 5. CNN Architecture Model with ResNet-101

This method enhances gradient flow, prevents vanishing gradients, and aids training of deep networks like ResNet-101. Residual blocks use a mix of 1×1, 3×3, and 1×1 convolutional layers. The first layer shrinks dimensions, the second extracts features, and the last layer expands dimensions. This layout allows the network to reach 101 layers while keeping training effective and performance high. ResNet-101 excels in image classification with a smart use of parameters. Adaptive shortcuts boost both stability and feature representation in the network [37]. ResNet-101 serves as a foundational model in image processing studies, notably for intricate image recognition like MBC. Below is a visual representation of the ResNet-101 residual block design:

|

| (4) |

Description, BN is the Batch Normalisation, helps stabilise and speed up training,  is the ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit), used as a nonlinear activation function.

is the ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit), used as a nonlinear activation function.  ,

,  ,

,  is the convolution weights with kernel size 1×1, 3×3, 1×1, Shortcut Ws is used if the input-output dimensions are different.

is the convolution weights with kernel size 1×1, 3×3, 1×1, Shortcut Ws is used if the input-output dimensions are different.

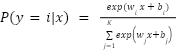

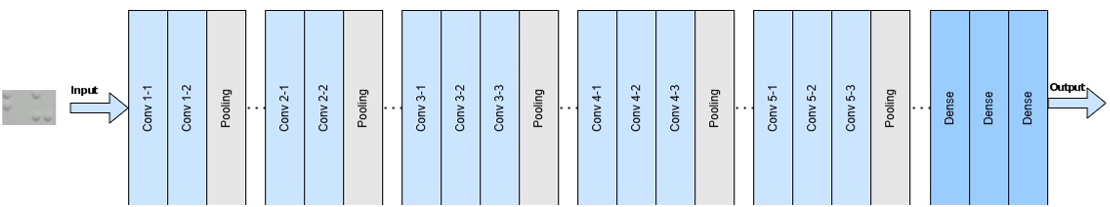

VGG-16 is one of the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architectures introduced by the Visual Geometry Group (VGG) of the University of Oxford in 2014, with a simple yet profound design [38]. The architecture comprises 16 trainable layers, incorporating 13 convolutional layers and 3 fully connected layers. The convolutional layers utilise a small convolutional filter of size 3 × 3, with padding and stride 1, and a pooling layer of size 2 × 2, with stride 2. In the VGG-16 model, each convolutional layer processes the input X ∈ ℝH × W × C into the output Y ∈ ℝH' × W' × C' through the following operation:

|

| (5) |

where W is a 3 × 3 convolution kernel, b(c') is the bias, and  is the ReLU activation function defined as σ(x) = max(0,x). After multiple convolution blocks, the spatial dimension is reduced using max pooling with the formula :

is the ReLU activation function defined as σ(x) = max(0,x). After multiple convolution blocks, the spatial dimension is reduced using max pooling with the formula :

|

| (6) |

where P is the pooling window (2 × 2) and s is the stride (2). VGG-16 ends with three fully connected layers, of which two have 4096 neurons, and the last has 1000 neurons (for the classification of 1000 classes in the ImageNet dataset) followed by a softmax function.

|

| (7) |

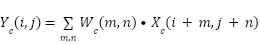

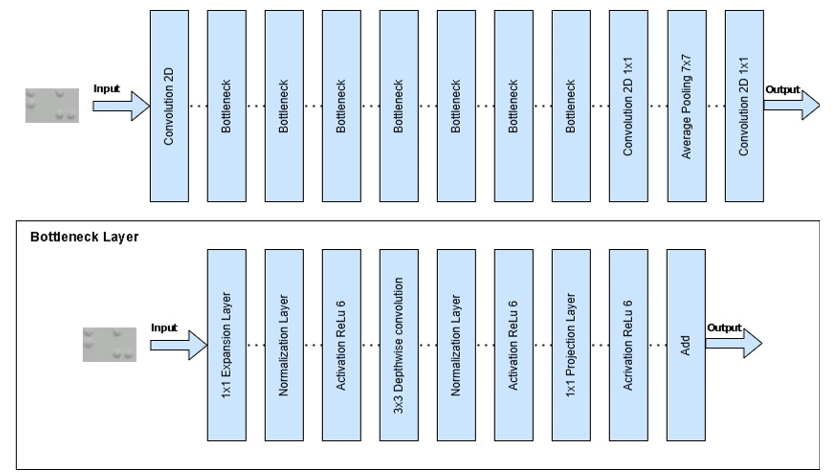

The primary benefit of the VGG-16 architecture lies in its architectural uniformity can be seen in Figure 6. This model employs diminutive 3×3 convolutional filters and extensive neural networks to derive intricate features from visual data [39]. MobileNetV2 uses depthwise separable convolution, which breaks down the convolution operation into two stages: depthwise convolution and pointwise convolution [40]. The depthwise convolution operation processes each channel separately, formulated as:

|

| (8) |

Figure 6. CNN Architecture Model with VGG-16

Conversely, pointwise convolution (1×11 × 11×1) combines these channels into the output:

|

| (9) |

The primary innovation in MobileNetV2 is the incorporation of inverted residual blocks with linear bottlenecks, which employ channel expansion through 1×11 × 11×1 convolutions (expansion layer), depthwise convolution for spatial feature extraction, and subsequent projection back to a lower dimension with 1×11 × 11×1 convolutions (compression layer) [41]. A residual connection facilitates a direct addition of input to output when spatial dimensions and channels align, expressed as:

|

| (9) |

where F(X) is the result of the transformation of the inverted residual block. Unlike other residual architectures, MobileNetV2 uses a linear bottleneck with the removal of the ReLU activation function at the bottleneck output, in order to minimise information loss in low-dimensional representations can be seen in Figure 7 [42]. The principal advantage of MobileNetV2 is its exceptional computational efficiency, resulting from a substantially lower number of parameters and floating-point operations (FLOPs) relative to conventional convolutional neural networks (CNNs), like VGG-16. This characteristic renders it exceptionally appropriate for deployment on devices with constrained resources [8]. The complex architectural structure requires precise adjustments for optimal performance in various applications.

Figure 7. CNN Architecture Model with MobileNet-V2

Evaluation

After training, an assessment on a test dataset measured the prowess of ResNet-50, ResNet-101, MobileNet-V2, and VGG16. This assessment calculated vital metrics including accuracy, error rate, and F1-score. Accuracy symbolizes the ratio of correct predictions to total predictions [43]. The aforementioned equation can be expressed in mathematical notation as follows:

|

| (10) |

Where TP is True Positive (correct prediction for positive class), TN is True Negative (correct prediction for negative class), FP is False Positive (incorrect prediction for positive class) and FN is False Negative (incorrect prediction for negative class). The error rate measures wrong predictions versus total predictions, revealing accuracy's opposite.

The F1-Score harmonizes precision and recall, making it ideal for skewed datasets. Precision and recall are defined as:

The F1-score is quantitatively represented as a percentage. The effectiveness of four CNN architectures will be evaluated on the test dataset through these metrics. Comparative evaluation results will be illustrated in a table and visual graphs for enhanced comprehension. Discrepancies in accuracy, error rate, and F1-score among the architectures will aid in determining the optimal CNN architecture for Braille word classification [39][40].

- RESULT AND DISCUSSION

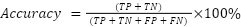

In this research, Braille characters were systematically displayed. Each display featured distinct forms of Braille, meticulously organized. Authentic media printed with precision birthed these sheets, captured under perfect lighting for clarity. Consistent dot patterns allow for meticulous data prep, like cropping and tagging. This refined dataset lays the groundwork for training a CNN model to identify and classify diverse MBC types. Figure 8 depicts a Braille sheet organized with Multi Braille Characters (MBC). We captured images using a stationary camera with controlled lighting to ensure dot-paper contrast. These sheets replicate real-world scenarios, presenting various two-character MBCs systematically. This imaging method was uniformly applied in the data preprocessing stage. Data preprocessing initiated with 3,150 MBC images from scanned Braille sheets. Two-character MBCs were extracted by cropping images utilizing calibrated bounding boxes. To improve generalization, brightness-based augmentation was performed, resulting in three variants per image. This method expanded the dataset to 9,450 images, thereby bolstering the model's resilience under varying lighting conditions.

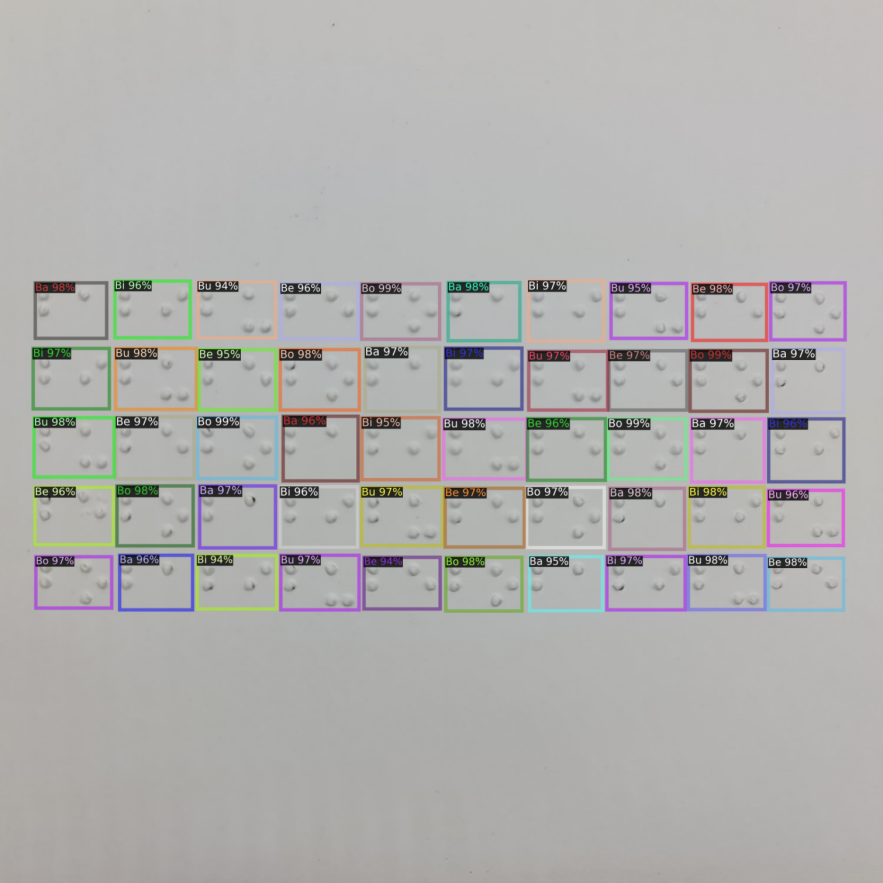

Each image is categorized by MBC for model training. This labeling is crucial for providing training data. The images are resized to 89 x 89 pixels for consistency in CNN input. Resizing is essential to mitigate discrepancies in classification. The dataset is partitioned into training, validation, and testing sets. This division follows a 70-20-10 ratio for allocation. Comprising 9,450 images across 105 MBC classes, the dataset ensures equitable distribution. Such thorough pre-processing is anticipated to improve the CNN model's training effectiveness for MBC classification. To assess the performance of various deep learning architectures in MBC classification, training was performed on a dataset of 9,450 images can be seen in Table 3. Each architecture—ResNet-50, ResNet-101, MobileNetV2, and VGG-16—was trained for 300 epochs, utilizing different batch sizes and default parameters. Critical metrics, including loss and accuracy, were evaluated for both training and validation datasets. This evaluation seeks to ascertain the model's generalization capacity and identify overfitting or underfitting. Graphical depictions of training results illustrate each model's performance trends during the training process. Figure 9 compares the training regimens, showcasing accuracy and loss over 300 epochs. The ResNet-101 model achieves over 90% validation accuracy with stability post-100 epochs, though validation loss increases, suggesting potential overfitting.

Figure 8. Results of taking pictures of Braille sheets were photographed under three 10W LED lights placed at 45° angles

Table 3. Augmented and truncated MBC Dataset

Figure 9. Accuracy and Loss graphs on ResNet-50 (a), ResNet-101 (b), MobileNet-V2 (c) and VGG-16 (d)

ResNet-50 mirrors ResNet-101's trend but with a lower validation accuracy peak, indicating that increased depth in ResNet-101 enhances feature extraction and classification. MobileNetV2, characterized by its efficiency, attains a validation accuracy of 84% but experiences greater fluctuations in performance, suggesting heightened sensitivity to data variations compared to ResNet models. In contrast, VGG-16 displays stagnant performance with validation accuracy between 60% and 70%, alongside high validation loss, indicating limited generalization capacity. Overall, ResNet-101 demonstrates superior accuracy and stability, while MobileNetV2 serves as a viable option in resource-limited contexts. Table 4 evaluates the performance of ResNet-101, ResNet-50, MobileNetV2, and VGG-16 based on accuracy, F1-Score, and error rate across varying batch sizes and epochs. ResNet-101 consistently outperforms in most scenarios, achieving 91.46% accuracy and 89.48% F1-Score with an 8.5% error rate, underscoring its proficiency in complex feature extraction. ResNet-50 shows reliable performance with some fluctuations, yielding slightly lower accuracy and F1-Score compared to ResNet-101, and serves as a balanced solution when computational resources are constrained. MobileNetV2 is noted for its efficient design and competitive performance, with accuracy of 84.81% at larger batch sizes despite higher error rates at smaller sizes, while VGG-16 lags with a maximum accuracy of only 61.71% and F1-Score of 55.31%, even with extended training durations. MobileNetV2’s performance instability is likely due to its lightweight depthwise convolutions, which may overlook subtle Braille dot variations—suggesting that future work could use augmented with techniques like brightness-based color jittering, enhancing its robustness in resource-constrained settings.

Table 4. Evaluation results

Skenario | ResNet101 | ResNet50 | MobileNetV2 | VGG-16 |

Batch | Epoch | Accu racy | F1 Score | Error Rate | Accu Racy | F1 Score | Error Rate | Accu racy | F1 Score | Error Rate | Accu racy | F1 Score | Error Rate |

8 | 50 | 38.61 | 30.75 | 61.39 | 63.92 | 59.92 | 36.08 | 2.22 | 0.91 | 97.78 | 44.62 | 38.03 | 55.38 |

16 | 61.07 | 54.2 | 38.92 | 75.95 | 73.96 | 24.05 | 5.70 | 3.17 | 94.30 | 55.06 | 47.54 | 44.94 |

32 | 77.21 | 72.47 | 22.78 | 72.78 | 71.06 | 27.22 | 19.94 | 14.99 | 80.06 | 46.20 | 38.94 | 53.80 |

64 | 81.01 | 76.50 | 18.99 | 76.58 | 73.97 | 23.42 | 70.25 | 65.57 | 29.75 | 56.96 | 49.94 | 43.04 |

128 | 81.96 | 78.71 | 18.04 | 76.27 | 73.18 | 23.73 | 73.42 | 69.45 | 26.58 | 59.18 | 53.23 | 40.82 |

8 | 100 | 71.20 | 66.84 | 28.80 | 71.2 | 66.4 | 28.80 | 3.16 | 1.56 | 96.84 | 53.16 | 45.69 | 46.84 |

16 | 80.70 | 76.09 | 19.30 | 73.1 | 68.86 | 26.90 | 19.30 | 13.72 | 80.70 | 58.54 | 52.50 | 41.46 |

32 | 85.44 | 81.95 | 14.56 | 74.68 | 70.83 | 25.32 | 44.94 | 39.59 | 55.06 | 56.65 | 49.82 | 4335 |

64 | 84.81 | 81.23 | 15.19 | 77.53 | 74.74 | 22.47 | 76.27 | 71.98 | 23.73 | 60.12 | 54.33 | 39.87 |

128 | 87.34 | 84.17 | 12.66 | 78.16 | 75.11 | 21.84 | 84.81 | 81.64 | 15.19 | 5.86 | 53.55 | 41.14 |

8 | 300 | 86.71 | 83.95 | 13.29 | 73.73 | 70.01 | 26.27 | 15.19 | 11.53 | 84.81 | 6.39 | 55.77 | 38.61 |

16 | 82.91 | 84.61 | 12.66 | 73.41 | 69.73 | 26.58 | 25.32 | 18.63 | 74.68 | 61.39 | 55.49 | 38.61 |

32 | 91.46 | 89.48 | 8.5 | 74.68 | 71.90 | 25.32 | 62.34 | 56.12 | 37.66 | 61.71 | 55.28 | 38.29 |

64 | 89.87 | 87.81 | 10.13 | 76.9 | 74.29 | 23.10 | 80.38 | 76.14 | 19.62 | 61.71 | 55.31 | 38.29 |

128 | 90.82 | 89.09 | 9.18 | 81.33 | 79.26 | 18.67 | 83.54 | 79.89 | 16.46 | 56.01 | 48.81 | 43.99 |

8 | 500 | 88.29 | 86 | 11.71 | 75.63 | 71.62 | 24.37 | 25 | 21.36 | 75 | 61.70 | 55.44 | 38.29 |

16 | 89.24 | 85.95 | 12.16 | 75.95 | 73 | 24.05 | 37.03 | 30.40 | 62.97 | 61.08 | 54.49 | 38.92 |

32 | 86.71 | 83.65 | 13.29 | 77.53 | 73.92 | 22.47 | 76.58 | 72.07 | 23.42 | 56.65 | 50.58 | 43.35 |

64 | 87.34 | 85.48 | 11.71 | 76.58 | 72.99 | 23.42 | 81.33 | 77.37 | 18.67 | 60.13 | 53.14 | 39.87 |

128 | 90.51 | 88.5 | 9.49 | 77.21 | 73.73 | 22.78 | 83.54 | 80.37 | 16.46 | 58.54 | 50.90 | 41.46 |

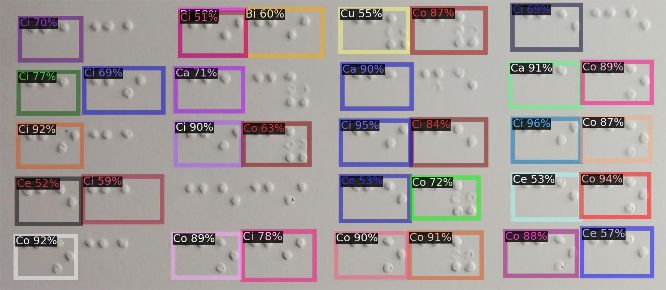

Overall, the findings of this assessment indicate that ResNet-101 represents the most superior architectural framework for the task of MBC classification within the context of this experiment. Furthermore, the amalgamation of a batch size of 32 and an epoch count of 300 constitutes the optimal configuration for achieving a harmonious equilibrium between elevated accuracy and a minimized error rate. This evaluation underscores the critical significance of selecting an appropriate architectural design and training configuration in the development of an effective and efficient image classification model. Figure 10 illustrates the output of the trained CNN model in detecting Multi Braille Characters (MBC) from a Braille sheet image. These results validate the robustness of the proposed CNN architecture—particularly ResNet-101—in handling spatial features essential for Braille recognition. Detection still has errors when there are errors in the braille dots or imperfect lighting which causes the shadow of the dots to not be formed perfectly for detection. Furthermore, the consistent accuracy across diverse syllables suggests that the model has successfully learned to generalize across the 105 class categories used in training. This detection capability marks a critical step toward the development of automated Braille reading systems that can support assistive technologies for visually impaired users.

The evaluation results indicate that ResNet-101 exhibits superior performance in Multi Braille Character classification, achieving optimal accuracy and F1-Score across varying batch sizes and training epochs. This underscores the importance of residual connections for effective gradient flow, facilitating the learning of robust feature representations essential for Braille recognition. ResNet-50, while slightly less accurate than ResNet-101, still showcases commendable performance, maintaining high accuracy and balancing depth with computational efficiency. Utilizing the same residual block architecture but fewer layers allow ResNet-50 to learn efficiently, making it suitable for hardware-constrained scenarios while performing adequately in Braille classification. Conversely, MobileNetV2 emphasizes efficiency, employing depth-wise convolutions and inverted residual blocks to minimize model size and computation. It achieves satisfactory accuracy, particularly when augmented with techniques like brightness-based colour jittering, enhancing its robustness in resource-constrained settings can be seen in Figure 10.

In contrast, VGG-16 consistently yields the lowest accuracy among the architectures, with the lack of residual connections hindering its capability to capture complex features necessary for Braille recognition. This is reflected in its significant performance disparity compared to contemporary models. Furthermore, the study's limitations include reliance on a singular dataset of printed Braille under controlled conditions, potentially constraining generalisation to real-world scenarios. Future investigations should incorporate diverse datasets, advanced data augmentation, and possibly hybrid models integrating linguistic or temporal context. In MBC classification, misclassifications often stem from similar dot patterns. Characters like "ba" and "pa" confuse due to overlapping dots. Additionally, edge-aligned characters near folds face misclassification risks from occlusions. Future enhancements should involve error heatmaps, spatial attention mechanisms, and tougher negative samples to boost model accuracy for similar MBC classes can be seen in Figure 11.

|

(a) |

|

(b) |

Figure 10. Evaluation with example images (a) not perfectly detected, (b) perfectly detected

Figure 11. Comparison chart of the four architectures

- CONCLUSIONS

This study is the first to specifically examine the classification of multi-character Braille (MBC) for Indonesian Braille. A comparative analysis of deep convolutional neural network architectures — namely ResNet-50, ResNet-101, MobileNetV2 and VGG-16 — was required for MBC recognition. This study has practical implications for the development of assistive technologies by demonstrating that CNN-based models can be customised for use in environments with limited resources, such as mobile devices or embedded systems for people with visual impairments. The dataset included 105 unique MBC classes, which underwent augmentation and preprocessing via cropping, brightness adjustment, annotation, and resizing to 89×89 pixels, resulting in 9,450 image samples. The results demonstrated that ResNet-101 consistently outperformed other architectures under various training conditions, achieving optimal accuracy, F1-score, and minimal error rates. The residual learning framework of ResNet-101, featuring deeper bottleneck blocks, effectively addressed the vanishing gradient problem, thus enhancing feature extraction and classification performance. This research lays a solid foundation for the development of automated Braille recognition systems, particularly for the Indonesian language. Indonesian's unique syllables and sounds demand a special method for recognizing multi-Braille characters. The MBC-based recognition approach offers increased granularity, beneficial for accurate Braille-to-text translation. The proposed system has significant potential for incorporation into assistive technologies, significantly aiding visually impaired individuals in accessing written content.

DECLARATION

Author Contribution

All authors contributed equally to the main contributor to this paper. All authors read and approved the final paper.

REFERENCES

- T. Kausar, S. Manzoor, A. Kausar, Y. Lu, M. Wasif, and M. Adnan Ashraf, “Deep Learning Strategy for Braille Character Recognition,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 169357–169371, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3138240.

- E.-G. Kim, S.-H. Park, S.-D. Cho, and J.-Y. Oh, “Braille Learning Helper for the Visually Impaired, Jumjarang,” Journal of the Korea Institute of Information and Communication Engineering, vol. 28, no. 12, pp. 1493–1500, 2024, https://doi.org/10.6109/jkiice.2024.28.12.1493.

- S. Shokat, R. Riaz, S. S. Rizvi, I. Khan, and A. Paul, “Characterization of English Braille Patterns Using Automated Tools and RICA Based Feature Extraction Methods,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 5, p. 1836, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/s22051836.

- R. Lupetina, “The Braille System: The Writing And Reading System That Brings Independence To The Blind Person,” European Journal of Special Education Research, vol. 8, no. 3, 2022, https://doi.org/10.46827/ejse.v8i3.4288.

- L. Lu, D. Wu, J. Xiong, Z. Liang, and F. Huang, “Anchor-Free Braille Character Detection Based on Edge Feature in Natural Scene Images,” Comput Intell Neurosci, vol. 2022, pp. 1–11, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/7201775.

- K. Doi, T. Nishimura, M. Takei, S. Sakaguchi, and H. Fujimoto, “Braille learning materials for Braille reading novices: experimental determination of dot code printing area for a pen-type interface read aloud function,” Univers Access Inf Soc, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 45–56, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-020-00709-8.

- Z. H. M. Jawasreh, N. Sahari Ashaari, and D. P. Dahnil, “The Acceptance of Braille Self-Learning Device,” Int J Adv Sci Eng Inf Technol, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 246–252, 2020, https://doi.org/10.18517/ijaseit.10.1.10263.

- N. Elaraby, S. Barakat, and A. Rezk, “A generalized ensemble approach based on transfer learning for Braille character recognition,” Inf Process Manag, vol. 61, no. 1, p. 103545, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2023.103545.

- P. Bhuse, B. Singh, and P. Raut, “Effect of Data Augmentation on the Accuracy of Convolutional Neural Networks,” In Information and Communication Technology for Competitive Strategies (ICTCS 2020) ICT: Applications and Social Interfaces, pp. 337–348, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-0739-4_33.

- A. AlSalman, A. Gumaei, A. AlSalman, and S. Al-Hadhrami, “A Deep Learning-Based Recognition Approach for the Conversion of Multilingual Braille Images,” Computers, Materials and Continua, vol. 67, no. 3, pp. 3847–3864, 2021, https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2021.015614.

- B.-M. Hsu, “Braille Recognition for Reducing Asymmetric Communication between the Blind and Non-Blind,” Symmetry (Basel), vol. 12, no. 7, p. 1069, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12071069.

- H. Wang, C. Zhu, and L. Bian, “Image-free multi-character recognition,” Opt Lett, vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 1343–1346, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.451777.

- M. M. González and D. M. Hardison, “Assistive design for English phonetic tools (ADEPT) in language learning,” Language Learning & Technology, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 1-23, 2022, https://doi.org/10.64152/10125/73493.

- T. Okamoto, T. Shimono, Y. Tsuboi, M. Izumi and Y. Takano, "Braille Block Recognition Using Convolutional Neural Network and Guide for Visually Impaired People," 2020 IEEE 29th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), pp. 487-492, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/ISIE45063.2020.9152576.

- D. R. Lim Roque, J. T. Marcelo Mateo, N. B. Linsangan, R. A. Juanatas, and I. Villamor, “Assistive Technology for Braille Reading using Optical Braille Recognition and Text-to-Speech,” in 2022 IEEE 14th International Conference on Humanoid, Nanotechnology, Information Technology, Communication and Control, Environment, and Management (HNICEM), pp. 1–6, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/HNICEM57413.2022.10109516.

- V. P. Revelli, G. Sharma, and S.Kiruthika devi, “Automate extraction of braille text to speech from an image,” Advances in Engineering Software, vol. 172, p. 103180, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advengsoft.2022.103180.

- R. Kumari, A. Dev, and A. Kumar, “An Efficient Syllable-Based Speech Segmentation Model Using Fuzzy and Threshold-Based Boundary Detection,” Int J Comput Intell Appl, vol. 21, no. 02, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1142/S1469026822500079.

- A. Al-Salman and A. AlSalman, “Fly-LeNet: A deep learning-based framework for converting multilingual braille images,” Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 4, p. e26155, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26155.

- A. AlSalman, A. Gumaei, A. AlSalman, and S. Al-Hadhrami, “A Deep Learning-Based Recognition Approach for the Conversion of Multilingual Braille Images,” Computers, Materials & Continua, vol. 67, no. 3, pp. 3847–3864, 2021, https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2021.015614.

- V. Venkatesh Murthy and M. Hanumanthappa, “VGG16 CNN based Braille Cell classifier model for Translation of Braille to Text,” Specialusis Ugdymas, vol. 1, no. 43, pp. 4388-4396, 2022, http://www.sumc.lt/index.php/se/article/view/527.

- V. Venkatesh Murthy and N. B. S, “Conversion of Braille Document to Regular English Document using VGG16 BC-CNN Model,” Grenze International Journal of Engineering & Technology (GIJET), vol. 10, 2024, https://openurl.ebsco.com/EPDB%3Agcd%3A10%3A35621418/detailv2?sid=ebsco%3Aplink%3Ascholar&id=ebsco%3Agcd%3A181690643&crl=c&link_origin=scholar.google.com.

- B.-S. Park et al., “Visual and tactile perception techniques for braille recognition,” Micro and Nano Systems Letters, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 23, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40486-023-00191-w.

- C. Li and W. Yan, “Braille Recognition Using Deep Learning,” in 2021 4th International Conference on Control and Computer Vision, pp. 30–35, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1145/3484274.3484280.

- M. Almasi, “Deep Learning and Neural Networks: Methods and Applications,” in Cutting-Edge Technologies in Innovations in Computer Science and Engineering, 2023, https://doi.org/10.59646/csebookc8/004.

- V. A. Golovko, A. A. Kroshchanka, and E. V. Mikhno, “Deep Neural Networks: Selected Aspects of Learning and Application,” Pattern Recognition and Image Analysis, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 132–143, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1134/S1054661821010090.

- A. Khan, A. Sohail, U. Zahoora, and A. S. Qureshi, “A survey of the recent architectures of deep convolutional neural networks,” Artif Intell Rev, vol. 53, no. 8, pp. 5455–5516, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-020-09825-6.

- S. P and R. R, “A Review of Convolutional Neural Networks, its Variants and Applications,” in 2023 International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Communication, IoT and Security (ICISCoIS), pp. 31–36, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICISCoIS56541.2023.10100412.

- S. Alufaisan, W. Albur, S. Alsedrah, and G. Latif, “Arabic Braille Numeral Recognition Using Convolutional Neural Networks,” In International Conference on Communication, Computing and Electronics Systems: Proceedings of ICCCES 2020, pp. 87–101, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-33-4909-4_7.

- P. Purwono, A. Ma’arif, W. Rahmaniar, H. I. K. Fathurrahman, A. Z. K. Frisky, and Q. M. ul Haq, “Understanding of Convolutional Neural Network (CNN): A Review,” International Journal of Robotics and Control Systems, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 739–748, 2023, https://doi.org/10.31763/ijrcs.v2i4.888.

- B. P. Sowmya and M. C. Supriya, “Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) Fundamental Operational Survey,” In International Conference on Innovative Computing and Cutting-edge Technologies, pp. 245–258, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65407-8_21.

- M. Sandler, A. Howard, M. Zhu, A. Zhmoginov, and L.-C. Chen, “MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks,” In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 4510-4520, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2018.00474.

- R. Scheps, “Geometry and the Life of Forms,” in Mathematics in the Visual Arts, pp. 29–52, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119801801.ch2.

- E. O. Pedersen, “The Beauty of Mathematical Order A Study of the Role of Mathematics in Greek Philosophy and the Modern Art Works of Piet Hein and Inger Christensen,” Journal of Somaesthetics, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 36-52, 2020, https://doi.org/10.5278/ojs.jos.v6i1.3667.

- A. Stone, “Measurement as a tool for painting,” Journal of Mathematics and the Arts, vol. 14, no. 1–2, pp. 154–156, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1080/17513472.2020.1732786.

- S. Srimamilla, “Image Classification Using Convolutional Neural Networks,” Int J Res Appl Sci Eng Technol, vol. 10, no. 12, pp. 586–591, 2022, https://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2022.47085.

- J. Miao, S. Xu, B. Zou, and Y. Qiao, “ResNet based on feature-inspired gating strategy,” Multimed Tools Appl, vol. 81, no. 14, pp. 19283–19300, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-021-10802-6.

- S. K. Sahu and R. N. Yadav, “Performance Analysis of ResNet in Facial Emotion Recognition,” n International Conference on Machine Intelligence and Signal Processing, pp. 639–648, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-0047-3_54.

- J. Lin, W. Liu, X. Li, S. Xiao, and Z. Yu, “An Asynchronous Convolution Process Engine forVGG-16 Neural Network,” in 2020 IEEE International Conference on Integrated Circuits, Technologies and Applications (ICTA), pp. 73–74, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICTA50426.2020.9332010.

- M. Ye et al., “A Lightweight Model of VGG-16 for Remote Sensing Image Classification,” IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens, vol. 14, pp. 6916–6922, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2021.3090085.

- P. Xiao, Y. Pang, H. Feng, and Y. Hao, “Optimized MobileNetV2 Based on Model Pruning for Image Classification,” in 2022 IEEE International Conference on Visual Communications and Image Processing (VCIP), pp. 1–5, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/VCIP56404.2022.10008829.

- L. Zhao, L. Wang, Y. Jia, and Y. Cui, “A lightweight deep neural network with higher accuracy,” PLoS One, vol. 17, no. 8, p. e0271225, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0271225.

- W. Jiang, H. Yu, and Y. Ha, “A High-Throughput Full-Dataflow MobileNetv2 Accelerator on Edge FPGA,” IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems, vol. 42, no. 5, pp. 1532–1545, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/TCAD.2022.3198246.

- V. Chang, M. A. Ganatra, K. Hall, L. Golightly, and Q. A. Xu, “An assessment of machine learning models and algorithms for early prediction and diagnosis of diabetes using health indicators,” Healthcare Analytics, vol. 2, p. 100118, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.health.2022.100118.

- A. Al Bataineh, D. Kaur, M. Al-khassaweneh, and E. Al-sharoa, “Automated CNN Architectural Design: A Simple and Efficient Methodology for Computer Vision Tasks,” Mathematics, vol. 11, no. 5, p. 1141, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/math11051141.

- K. M. Ang et al., “Optimal Design of Convolutional Neural Network Architectures Using Teaching–Learning-Based Optimization for Image Classification,” Symmetry (Basel), vol. 14, no. 11, p. 2323, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/sym14112323.

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

| Made Ayu Dusea Widyadara an eager student at the Universitas Negeri Malang’s Electrical Engineering department. She dives into the realms of Computer Vision, Deep Learning, and Assistive Tech. Currently, she’s crafting a Braille recognition system with CNNs to enhance accessibility for the visually impaired. Email: made.ayu.2305349@students.um.ac.id ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0834-1849 Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=58939671800 Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=8iThwhEAAAAJ&hl=en |

|

|

| Anik Nur Handayani is a senior lecturer and researcher in the Department of Electrical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia. Her research areas include Digital Image Processing, Machine Learning, Embedded Systems, and Smart Assistive Technologies. She has been actively involved in various national research projects and has published numerous scientific works related to computer vision and human-computer interaction. Email: anik.nur.ft@um.ac.id ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-0767-8471 Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57193701633 Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=nqPHjbMAAAAJ&hl=en |

|

|

| Heru Wahyu Herwanto is a faculty member in the Department of Electrical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia. His research focuses on embedded systems, digital signal processing, Internet of Things (IoT), and machine learning applications. He has contributed to various scientific publications and national research programs in the field of intelligent systems and automation. Email: heru.wahyu.ft@um.ac.id ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-0796-3596 Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57194026701 Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.co.id/citations?user=XZq2mHkAAAAJ&hl=id |

|

|

| Boyang (Tony) Yu is a researcher and technology specialist with expertise in Artificial Intelligence, Computer Vision, and Data Analytics. His professional background includes research in image processing and AI system development, with applications across assistive technologies and human-centered computing. He has authored scientific publications and actively shares insights on emerging AI trends. Email : by12@rice.edu ORCID : https://orcid.org/0009-0005-2827-9976 Google Scholar : https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=M23icsAAAAAJ&hl=en |

Made Ayu Dusea Widyadara (A Generalized Deep Learning Approach for Multi Braille Character (MBC) Recognition)