ISSN: 2685-9572 Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro

Vol. 7, No. 3, September 2025, pp. 296-311

A New Adaptive Flux-Oriented Control Framework for Induction Motors with Online Neural Network Training

Belkacem Bekhiti 1, Raheem Al-Sabur 2, Abdel-Nasser Sharkawy 3,4

1 Institute of Aeronautics and Space Studies, (IASS), University of Blida 1 BP 270 Blida (09000), Algeria

2 Mechanical Department, Engineering College, University of Basrah, Basrah 61004, Iraq

3 Mechanical Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, South Valley University, Qena 83523, Egypt

4 Mechanical Engineering Department, College of Engineering, Fahad Bin Sultan University, Tabuk 47721, Saudi Arabia

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 21 May 2025 Revised 08 July 2025 Accepted 20 July 2025 |

|

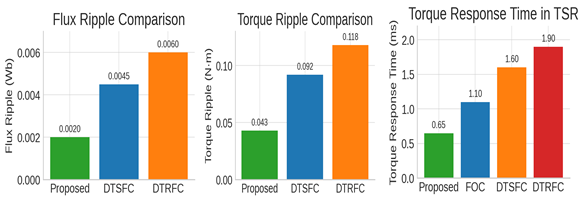

Unlike conventional field oriented control methods, this paper presents a mathematically novel control strategy for induction motor drives, formulated using a two-loop nonlinear dynamic inversion (NDI) framework inspired by aeronautical control architectures. Sensorless operation is realized with a conventional rotor-flux observer, while several additional enhancements are introduced to raise overall performance. In particular, a real-time radial-basis-function (RBF) neural network is systematically embedded in a model-reference adaptive system (MRAS), replacing the traditional PI adaptation loop with an online-training mechanism that improves speed estimation accuracy under parameter variations and load disturbances. The single-layer RBF network is trained by gradient descent and incorporated into the nonlinear observer without compromising closed-loop stability. The complete controller was implemented on a 1.1 kW, 1430 rpm induction motor using a dSPACE DS1104 real-time platform. Experimental results show clear superiority over classical FOC as well as DTSFC and DTRFC schemes, achieving the lowest measured flux ripple (0.002 Wb), minimal torque ripple (0.043 N·m), and the fastest torque response time (0.65 ms). The steady-state speed error was reduced by 91 % (from 0.65 to 0.08 rad/s), settling times remained below 60 ms, and both RMSE and ISE metrics decreased appreciably across all tested conditions. Although the proposed design incurs moderate computational overhead, it is fully compatible with real-time execution. Future work will examine scalability to high-power drives, improved resilience to temperature-induced parameter drift, and adaptation of the NDI-based framework to permanent-magnet machines. |

Keywords: Torque Ripple Reduction; Online RBF Network; MRAS-based Neural Adaptation; Flux-Oriented Control; Real-Time Adaptive Control |

Corresponding Author: Abdel-Nasser Sharkawy, Mechanical Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, South Valley University, Qena 83523, Egypt. Email: abdelnassersharkawy@eng.svu.edu.eg |

This work is open access under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: B. Bekhiti, R. Al-Sabur and A. -N. Sharkawy, “A New Adaptive Flux-Oriented Control Framework for Induction Motors with Online Neural Network Training,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 296-311, 2025, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v7i3.13727. |

INTRODUCTION

Recent advancements in electric drive systems have intensified research on the control and observation of induction motors (IMs), especially under sensorless and nonlinear conditions. A key challenge is achieving accurate rotor speed estimation to enhance efficiency and reliability. Bennassar [1] proposed a hybrid observer combining fuzzy Luenberger observers with Kalman filters for improved sensorless control. Rihar [2] emphasized integrating emerging technologies in power electronics and intelligent machine design for next-generation drives. Sliding mode control, known for robustness, was enhanced by Shiravani [3], though it often suffers from chattering. Neural networks offer promising solutions for handling nonlinearities and dynamics; Menghal and Laxmi [4] demonstrated dynamic IM drive simulations using neural networks, while Sengamalai [5] reviewed modeling, parameter estimation, and control, highlighting adaptive and intelligent methods in current research. Speed estimation techniques have also evolved significantly. Kubota introduced a DSP-based adaptive flux observer, which marked a seminal step in industrial sensorless IM control [6]. Later, Medjadji proposed a fuzzy-MRAS observer with experimental validation, contributing to the reduction of estimation errors [7]. Adaptive robust techniques, such as those using Multidimensional Taylor Networks [8] and those applied to permanent magnet synchronous machines [9], have pushed control performance further by integrating robustness and learning abilities. Incorporating fuzzy logic into IM control also gained attention. Mekrini et al. [10] demonstrated intelligent fuzzy logic strategies for asynchronous machines. Similarly, Hamdi [11] proposed a deadbeat MRAS-based sensorless control scheme. Sujatha and Vaisakh [12] introduced an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) for speed control, and Stewart et al. [13] explored the use of evolutionary algorithms in the robust tuning of fuzzy logic controllers. The foundational theory of fuzzy systems by Takagi and Sugeno [14] underpins many of these developments.

Building on adaptive control frameworks, Bekhiti et al. [15] recently validated a hyper-stability-based nonlinear multivariable control strategy on induction motors, presenting robust experimental results. Bekhiti et al. also investigated observer-based sensorless control using extended Kalman filters [16], and provided an overview of advanced nonlinear control and state estimation in robotic systems [17]. Adaptive neuro-fuzzy techniques are now being extended to broader applications. For example, Mostfa et al. [18] used ANFIS models in wind energy, and Kheioon et al. [19][20] applied similar principles in robotic gripping systems. In parallel, Saputra et al [21] assessed the performance of sliding mode control in DC motor systems, confirming its relevance as a benchmark. As AI techniques continue to evolve, neural controllers are now coupled with fractional-order stability analysis [22], fuzzy inference [23], and various learning models for IM drives. Speed estimation via artificial neural networks (ANN) has also been extensively studied [24][25]. Additionally, Demirtas et al. [26] employed Pareto-optimized fractional-order controllers using Elman neural networks, while Brandstetter and Kuchar [27] implemented RBF neural networks for sensorless variable-speed control. Neural-based drive control has been extended to electric vehicles [28], and online-trained fuzzy neural systems have achieved real-time adaptive control [29]. Intelligent MRAS systems using feed-forward neural networks [30] and adaptive Type-II fuzzy logic [31] have further enhanced sensorless estimation capabilities. Other techniques, such as immersion and invariance control [32] and robust MRAS approaches [33] have contributed to more stable and adaptive speed regulation. Recent strategies combine nonlinear adaptive control with observer design. For instance, Ren et al. [34] introduced a perturbation-based nonlinear observer, while Travieso-Torres et al. [35] applied normalized MRAC to scalar control schemes. Beyond control, extensive neural network studies (including architectures [36], edge intelligence [37], and training optimization [38] provide foundational tools for enhancing induction motor control performance in complex environments.

This paper proposes a new adaptive field-oriented control (FOC) framework for induction motors, which innovatively integrates nonlinear state observation and online neural network learning into a novel proposed FOC structure. While traditional adaptive and intelligent control strategies have been widely investigated [1]-[6], they often suffer from limited robustness to time-varying uncertainties or require exact model knowledge. The novelty of this work lies in developing a sensorless control scheme that adapts online to dynamic conditions without compromising the modularity and intuitive tuning benefits of the FOC approach. The main contributions are summarized as follows:

- Nonlinear Observer-Based Field Orientation: A nonlinear observer estimates rotor flux and speed, eliminating the need for mechanical sensors and enhancing robustness to model uncertainties.

- Online Neural Network Learning: A single-layer neural network approximates unknown nonlinearities and disturbances in real time, enabling fast adaptation under variable loads.

- Real-Time Implementation and Validation: The proposed architecture is experimentally validated on a dSPACE-based induction motor test bench, and benchmarked against conventional MRAS and PI-tuned FOC schemes [7],[10],[16],[24].

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the mathematical model of the induction motor and revisits the conventional field-oriented control (FOC) scheme to establish a baseline. Section 3 introduces the proposed adaptive FOC framework, detailing the nonlinear flux observer, the neural network-based online learning mechanism, and the overall control architecture, along with a rigorous Lyapunov-based stability analysis to ensure global boundedness and convergence. Section 4 reports experimental and real-time validation results using a dSPACE DS1104 platform, demonstrating the performance of the proposed method under various operating scenarios, including abrupt speed and load variations. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

THE INDUCTION MOTOR AND THE PROPOSED FIELD-ORIENTED CONTROL

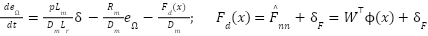

To design a robust and adaptive field-oriented control strategy, a precise dynamic model of the induction motor is essential. This section begins by presenting the nonlinear state-space model of an induction motor expressed in the stator reference frame. The model captures the coupled electromechanical behavior of the system, including the flux, current, and speed dynamics, and provides the foundation for the subsequent development of the proposed adaptive control framework.

The Induction Motor Model

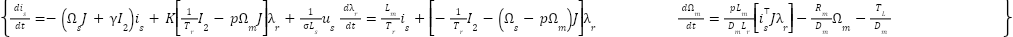

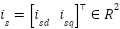

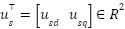

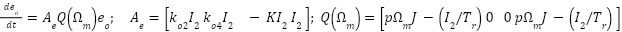

Consider a squirrel-cage induction motor in the stator reference frame rotating at an angular speed  . Let

. Let  be the stator current vector,

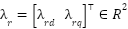

be the stator current vector,  the rotor flux vector, and

the rotor flux vector, and  the mechanical speed. The motor dynamics are given by [15]:

the mechanical speed. The motor dynamics are given by [15]:

|

| (1) |

Where:  is the stator current vector in the

is the stator current vector in the  frame,

frame,  is the rotor flux linkage vector in the

is the rotor flux linkage vector in the  frame,

frame,  is the stator voltage vector in the

is the stator voltage vector in the  frame,

frame,  is the angular frequency of the rotating reference frame (usually synchronous speed)

is the angular frequency of the rotating reference frame (usually synchronous speed)  ,

,  is the rotor mechanical speed

is the rotor mechanical speed ,

,  is the stator inductance

is the stator inductance  ,

,  is the rotor inductance

is the rotor inductance  ,

,  is the mutual inductance between the stator and rotor

is the mutual inductance between the stator and rotor  ,

,  is the stator resistance

is the stator resistance  ,

,  is the rotor resistance

is the rotor resistance  ,

,  is the mechanical friction coefficient

is the mechanical friction coefficient ,

,  is the total inertia constant (inertia + damping equivalent)

is the total inertia constant (inertia + damping equivalent)  ,

,  is the load torque

is the load torque  ,

,  is the number of pole pairs, and

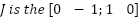

is the number of pole pairs, and  : the canonical rotation matrix,

: the canonical rotation matrix,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

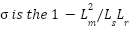

,  : total leakage coefficient.

: total leakage coefficient.

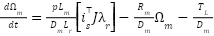

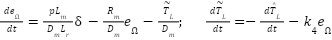

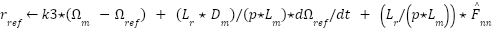

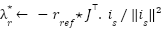

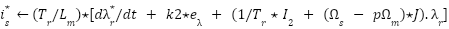

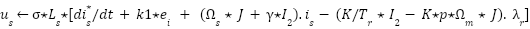

The Proposed Control Structure

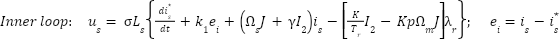

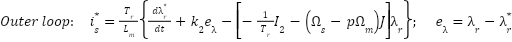

The proposed control strategy is organized hierarchically to achieve precise torque and flux regulation. It relies on an inner–outer loop structure for effective decoupling and stabilization of the induction motor dynamics. This section presents the fundamental layout of the control scheme, excluding the adaptive neural network module, which will be introduced separately in the next section to emphasize its learning and compensation capabilities. The control structure is designed hierarchically as follows:

- The flux control is structured into an inner–outer loop:

|

| (2) |

|

| (3) |

- The flux reference orientation: To achieve flux reference orientation, the rotor flux vector is aligned such that the cross-product

tracks a desired regulation signal

tracks a desired regulation signal  (i.e.

(i.e.  ); this yields the explicit formula

); this yields the explicit formula  , enabling dynamic coupling with the speed control objective.

, enabling dynamic coupling with the speed control objective. - The speed regulation: To linearize the mechanical dynamics and achieve precise speed regulation, we shape

as a composite feedforward-feedback law, incorporating proportional feedback on the speed error, feedforward compensation of the reference acceleration, and disturbance rejection via estimated load torque:

as a composite feedforward-feedback law, incorporating proportional feedback on the speed error, feedforward compensation of the reference acceleration, and disturbance rejection via estimated load torque:

|

| (4) |

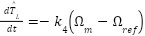

- The load torque estimation: The estimated load torque

is generated by a simple observer:

is generated by a simple observer:

|

| (5) |

Here,  are control gains, and

are control gains, and  is the desired speed trajectory. Under the control laws defined above for the stator current inner loop, rotor flux outer loop, and mechanical speed regulation via reference shaping and torque observation, the closed-loop system is globally asymptotically stable. In particular, all tracking errors

is the desired speed trajectory. Under the control laws defined above for the stator current inner loop, rotor flux outer loop, and mechanical speed regulation via reference shaping and torque observation, the closed-loop system is globally asymptotically stable. In particular, all tracking errors  ,

,  , and

, and  converge to zero as

converge to zero as  .

.

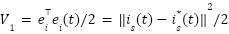

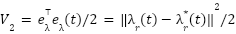

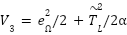

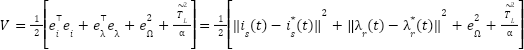

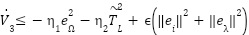

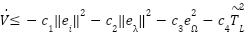

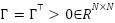

Proof We proceed using composite Lyapunov analysis to address the hierarchical nature of the system. Let us define three positive definite functions:

- Current error energy:

- Flux error energy:

- Speed tracking and load torque estimation:

with

with

Here,  is a scalar to tune the weight of the torque estimation error. We now define the total Lyapunov function:

is a scalar to tune the weight of the torque estimation error. We now define the total Lyapunov function:

|

| (6) |

Now, we compute the time derivatives of Lyapunov candidates

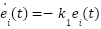

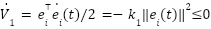

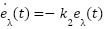

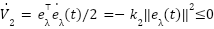

- From the inner loop control law (2), we get the closed-loop error dynamics:

means that

means that  .

. - Substituting the outer loop control law (3) into rotor flux dynamics then:

means that

means that  .

. - From the Speed dynamics, the mechanical equation is:

|

| (7) |

Let:  and use:

and use:  with

with , then make substitution into dynamics:

, then make substitution into dynamics:

|

| (8) |

Knowing that:  , so after substitution:

, so after substitution:

|

| (9) |

Regroup terms:

|

| (10) |

By completing the square and bounding  , we can make:

, we can make:  for suitable positive

for suitable positive  ,

, , and small coupling

, and small coupling  .

.

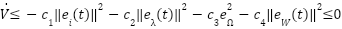

- For global asymptotic stability, we combine all parts:

for positive constants

for positive constants  . Hence:

. Hence:  as

as  so

so  ,

,  , and

, and  converge to zero. The closed-loop hierarchical controller ensures global asymptotic stability under the proposed control laws, with all internal loops exponentially stable and all tracking errors vanishing as

converge to zero. The closed-loop hierarchical controller ensures global asymptotic stability under the proposed control laws, with all internal loops exponentially stable and all tracking errors vanishing as  .

.

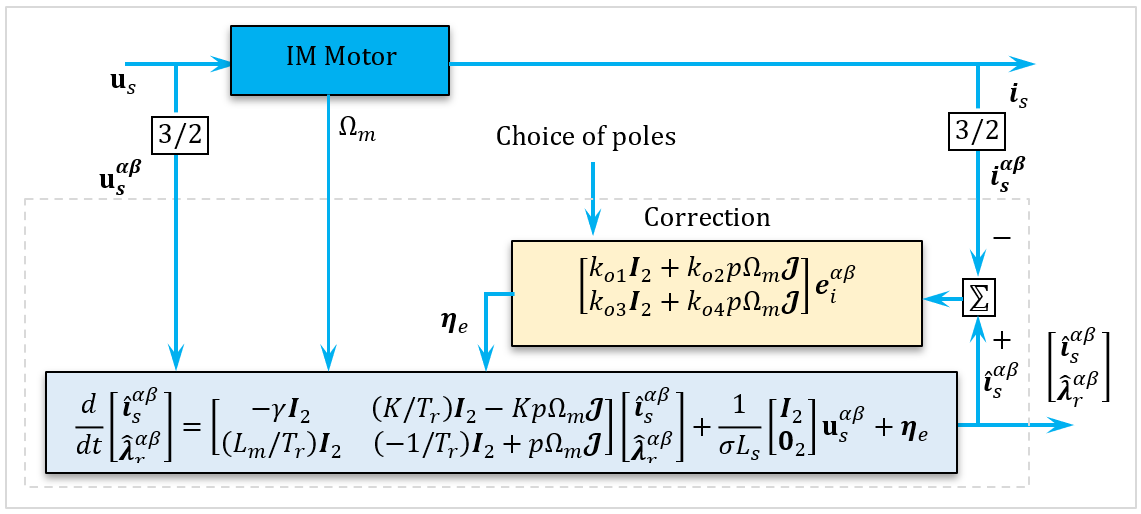

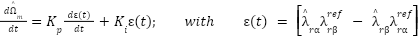

A foundational reference in IM observer design is the work introduced by Verghese and Sanders [39], which has since inspired several variants, including those proposed by De Luca and Ulivi [40], Xie et al. in [41], and by Bekhiti et al. [16]. The general structure of this classical observer is given by:

|

| (11) |

where  ,

,  ,

,  , the

, the  being scalars and

being scalars and  . Note that the gains depend on the speed in (11). We show the diagram block of this observer in Figure 1.

. Note that the gains depend on the speed in (11). We show the diagram block of this observer in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Closed-loop flux observer block diagram

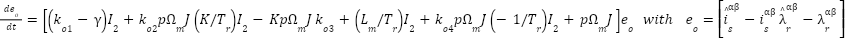

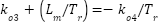

The resulting model for the observer error dynamics is then

|

| (12) |

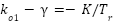

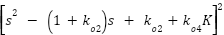

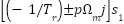

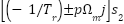

Note that we can freely determine the scalar coefficients in equation (12). If  and

and  are selected such that

are selected such that  ,

,  the error dynamics become

the error dynamics become

|

| (13) |

We select  and

and  to place the eigenvalues of

to place the eigenvalues of  in arbitrary positions. Note that the characteristic polynomial of

in arbitrary positions. Note that the characteristic polynomial of  is

is  . If the eigenvalues of

. If the eigenvalues of  are

are  and

and  (twice), then the eigenvalues of time varying matrix

(twice), then the eigenvalues of time varying matrix  are

are  and

and  using the slow dynamics theory. The observer used in (11) follows the general structure introduced in

using the slow dynamics theory. The observer used in (11) follows the general structure introduced in  , but adopts improved stability conditioning and gain scheduling commonly seen in later variants such as

, but adopts improved stability conditioning and gain scheduling commonly seen in later variants such as  and

and  .

.

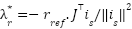

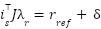

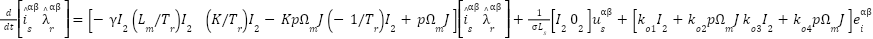

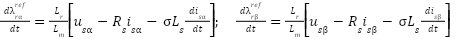

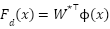

Rotor speed  is estimated using a model reference adaptive system (MRAS) consisting of a reference model and an adaptive model. Both compute the rotor flux components

is estimated using a model reference adaptive system (MRAS) consisting of a reference model and an adaptive model. Both compute the rotor flux components  and

and  in the stationary 𝛼𝛽 frame. The adaptive model tunes its speed estimate to minimize the flux discrepancy. The reference model, based on stator voltage equations, is speed-independent and suitable for robust flux estimation

in the stationary 𝛼𝛽 frame. The adaptive model tunes its speed estimate to minimize the flux discrepancy. The reference model, based on stator voltage equations, is speed-independent and suitable for robust flux estimation  . Its expression in the stationary frame is:

. Its expression in the stationary frame is:

|

| (14) |

In contrast, the adaptive model, formulated from the rotor voltage equations, explicitly depends on the rotor flux components and the estimated speed  . It is expressed as:

. It is expressed as:

|

| (15) |

The angular discrepancy between the estimated and reference flux vectors serves as the adaptation signal, which is processed by a linear PI controller to adjust the estimated speed. Applying the Popov  criterion

criterion  to guarantee global asymptotic stability of the closed-loop estimation system, the adaptive law is given by:

to guarantee global asymptotic stability of the closed-loop estimation system, the adaptive law is given by:

|

| (16) |

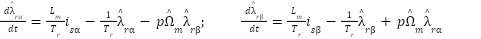

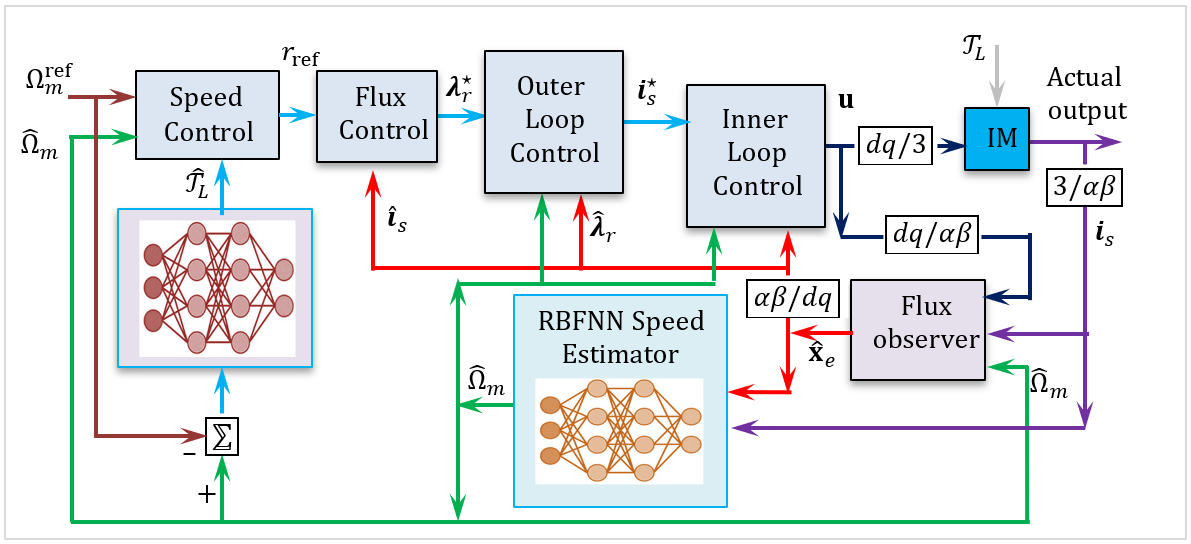

The overall architecture of the non-intelligent sensorless adaptive flux-oriented controller is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Diagram of the proposed adaptive sensorless control scheme for induction motor drive

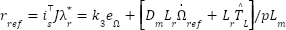

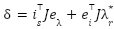

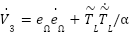

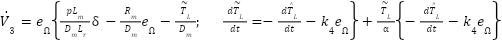

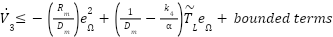

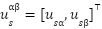

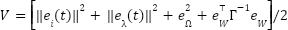

The Proposed Neural Adaptive FOC Control

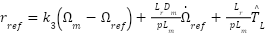

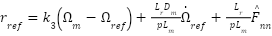

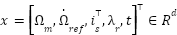

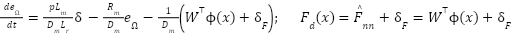

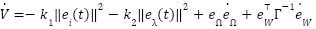

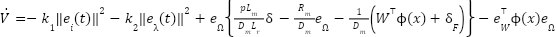

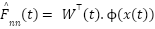

To enhance the previous strategy with a Radial Basis Function (RBF) Neural Network for improved speed regulation and robustness against modeling uncertainties and un-modeled load torque, we propose the following augmented control strategy and stability proof based on Lyapunov theory with neural network adaptation. We retain the same motor dynamics and hierarchical control structure but modify the speed regulation law by introducing an RBF neural network to approximate unknown dynamics and disturbance terms in the mechanical subsystem:

- We replace the estimated load torque

with an online RBF neural network estimate

with an online RBF neural network estimate  , yielding:

, yielding:

|

| (17) |

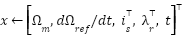

Where,  , an adaptive RBF neural network,

, an adaptive RBF neural network,  is the input vector,

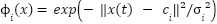

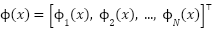

is the input vector,  is the vector of radial basis functions (e.g., Gaussian kernels),

is the vector of radial basis functions (e.g., Gaussian kernels),  is the adaptive weight vector,

is the adaptive weight vector,  estimates the unknown disturbance and nonlinear terms

estimates the unknown disturbance and nonlinear terms  .

.

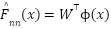

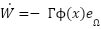

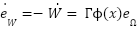

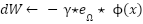

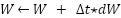

- We adopt a gradient descent rule for online weight adaptation:

where, the matrix

where, the matrix  is a positive definite adaptation gain matrix.

is a positive definite adaptation gain matrix. - We define the augmented Lyapunov function incorporating the neural network weights:

|

| (18) |

where  is the ideal weight vector that exactly reproduces

is the ideal weight vector that exactly reproduces  .

.

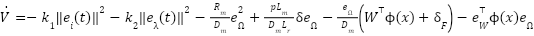

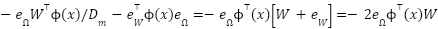

From the mechanical dynamics:

|

| (19) |

We have to write:

|

| (20) |

Time derivative of the Lyapunov function  Substitute

Substitute  :

:

|

| (21) |

Now group terms:

|

| (22) |

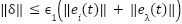

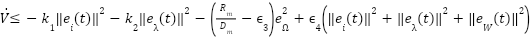

Observe that:  and treat

and treat  and

and  as bounded coupling terms. Assume

as bounded coupling terms. Assume  ,

,  . Then:

. Then:

|

| (23) |

Choosing adaptation gain and control gains sufficiently large ensures:

|

| (24) |

Hence, all signals are bounded and

,

, ,

,  ,

,  as

as  .

.

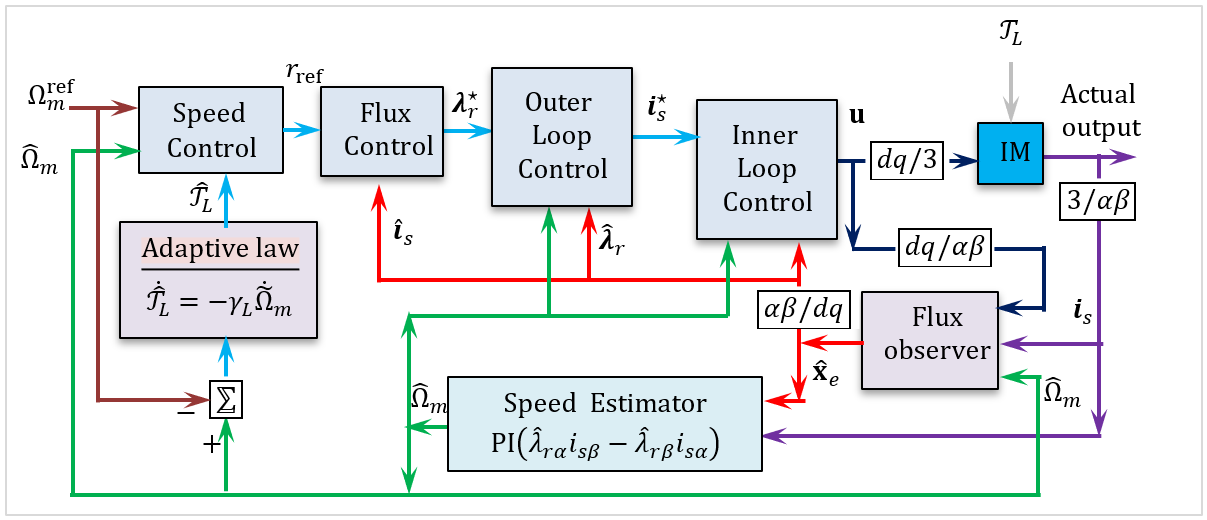

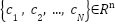

The integration of a single-layer RBF neural network into the proposed field-oriented control strategy enables online learning and compensation of unmodeled dynamics and external disturbances, effectively replacing the conventional load torque observer with a model-free adaptive approximation. Selected for its fast convergence, low computational cost, and ease of online training, the RBF model is well suited for real-time motor control compared to deeper or kernel-based alternatives such as DNNs or SVMs. This enhancement not only improves robustness against parameter uncertainties and time-varying loads but also preserves the global asymptotic stability of the overall system through a modified Lyapunov-based adaptive design that ensures convergence of all tracking errors despite the presence of approximation errors. The overall architecture of the intelligent sensorless adaptive flux-oriented controller is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Diagram of the proposed neural-adaptive sensorless control scheme for induction motor drive

Here is a concise and structured pseudocode summarizing the complete RBF neural network training algorithm for adaptive control applications:

Input:

, ,

Initial states: | ← Number of RBF neurons ← Input dimension (e.g., 5) ← Learning rate for RBF weights ← Gains for inner and outer loops (current/flux) ← Speed regulation gain ← Width of RBF  ← Integration step ← Optional weight norm bound  , ,  , ,  , ,

|

Output: Online-adapted weights  , motor control input u_s(t) , motor control input u_s(t)  Step 1: RBF Initialization Step 1: RBF Initialization

1. Choose RBF centers   Use K-means or uniform grid Use K-means or uniform grid 2. Set RBF widths  (e.g., common (e.g., common  ) ) 3. Initialize weights  (or from offline least-squares if data is available) (or from offline least-squares if data is available)  Step 2: Control Loop (per time step Step 2: Control Loop (per time step  ) )

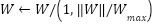

Loop for each time step t:  --- Measure system states and references --- --- Measure system states and references ---   Input to RBF network Input to RBF network  , ,  , ,  , ,  (if known) ← sensors or observers (if known) ← sensors or observers  , ,  ← trajectory generator ← trajectory generator  --- RBF Network: Estimate unknown torque term --- --- RBF Network: Estimate unknown torque term --- For  : :  EndFor EndFor  ; ;   --- Reference shaping with RBF correction --- --- Reference shaping with RBF correction ---   --- Flux orientation: compute --- Flux orientation: compute  --- --- If  : :  Else: Else:  EndIf EndIf  --- Outer flux loop: compute --- Outer flux loop: compute  --- ---  ; ;  ← differentiate ← differentiate  or approximate or approximate   --- Inner current loop: compute control input --- Inner current loop: compute control input  --- ---  ; ;  ← differentiate ← differentiate  or approximate or approximate   --- Apply --- Apply  to motor system --- to motor system --- Apply  to stator winding to stator winding  --- Online RBF weight update --- --- Online RBF weight update ---

|  Speed tracking error Speed tracking error

Gradient descent adaptation Gradient descent adaptation

Euler integration step Euler integration step

|

--- Projection to constrain W norm (limits --- Projection to constrain W norm (limits  to prevent instability from unbounded learning) --- to prevent instability from unbounded learning) --- If  : :  EndIf EndIf  Clip or rescale Clip or rescale EndLoop |

Note: The use of multiple trained neural networks in induction motor control offers notable gains in adaptability and precision, especially under uncertainty and nonlinearity [42]-[47]. These models learn complex system behavior and improve tracking across operating conditions. Compared to the torque estimation in (5), the RBF-based approach yields better compensation during load changes, enhancing torque response and reducing ripple. However, this comes with added computational cost, complexity, and risk of overfitting, particularly without diverse training data. For real-time applications, a balance between model accuracy and execution efficiency is essential. Thus, embedding neural learning within adaptive or observer-based frameworks remains a practical and robust option for industrial use.

- EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

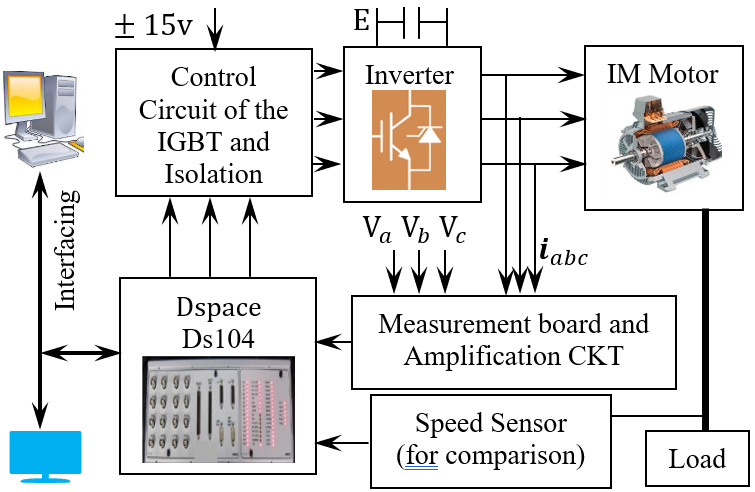

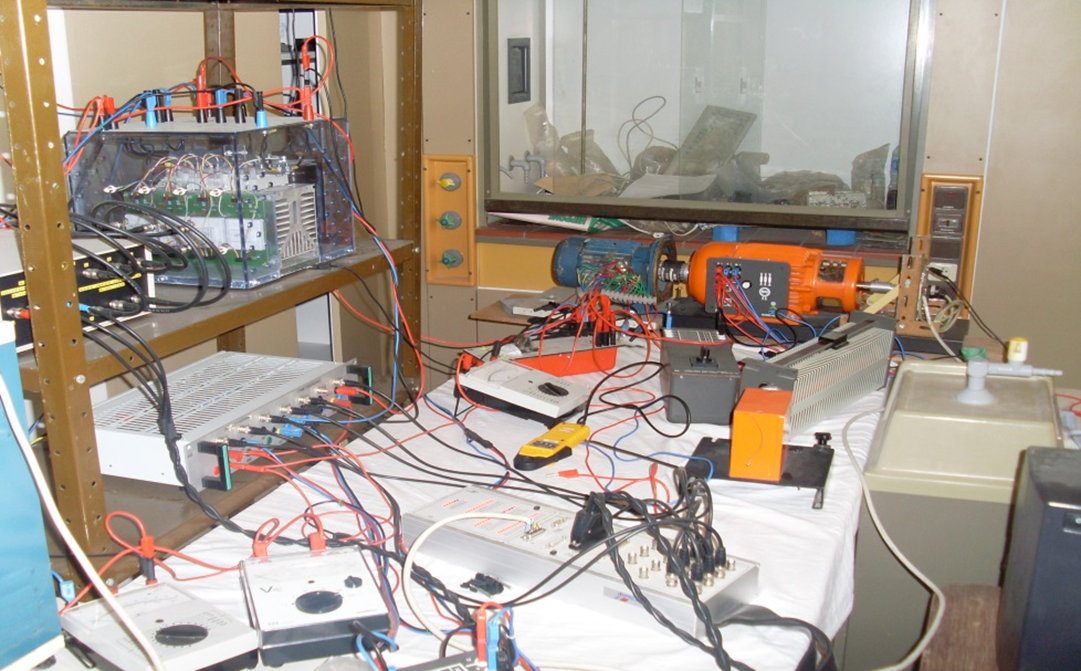

The effectiveness of the proposed neural adaptive controller was assessed through a comprehensive experimental setup, as illustrated in Figure 4, which consists of the following components: Three-phase asynchronous motor with rated values: Rated voltage:  , Rated current:

, Rated current:  , Rated power:

, Rated power:  , Rated speed:

, Rated speed:  , Frequency:

, Frequency:  , Number of phases: 3, Synchronous machine with powder brake for loading the IM. Electronic power converter (without any control system): 3

, Number of phases: 3, Synchronous machine with powder brake for loading the IM. Electronic power converter (without any control system): 3 (three-phase) diode rectifier and VSI composed of three

(three-phase) diode rectifier and VSI composed of three  modules electronic card for monitoring the stator phase with Instantaneous voltage sensors (

modules electronic card for monitoring the stator phase with Instantaneous voltage sensors ( -

- ) and Instantaneous current sensors (

) and Instantaneous current sensors ( -

- ) Voltage sensor for monitoring the instantaneous value of the dc-link voltage. (Model

) Voltage sensor for monitoring the instantaneous value of the dc-link voltage. (Model  -

- ) Incremental encoder only for comparison measurements. Model RS 256-499, 2500 pulses per round, (only for validation-comparison, not feedback control)

) Incremental encoder only for comparison measurements. Model RS 256-499, 2500 pulses per round, (only for validation-comparison, not feedback control)  card (

card ( ) with a PowerPC

) with a PowerPC  at

at  and floating-point digital signal processor

and floating-point digital signal processor  . During the real-time operation of the control, the supervision/capturing of the important data can be done by the

. During the real-time operation of the control, the supervision/capturing of the important data can be done by the  software provided with

software provided with  board. The control loop operates at 20 kHz, while the current and voltage sensors are sampled at 12 kHz. Simulations in MATLAB verified the proposed control scheme using a rated flux reference and

board. The control loop operates at 20 kHz, while the current and voltage sensors are sampled at 12 kHz. Simulations in MATLAB verified the proposed control scheme using a rated flux reference and  DC-link voltage. The feedback signal reconstruction was confirmed in simulation, and experimental results further validated the effectiveness and robustness of the sensorless control strategy. The electrical and mechanical parameters of the induction motor are listed in Table 1.

DC-link voltage. The feedback signal reconstruction was confirmed in simulation, and experimental results further validated the effectiveness and robustness of the sensorless control strategy. The electrical and mechanical parameters of the induction motor are listed in Table 1.

Figure 4. Experimental setup for the proposed neural-fuzzy MRAS control of the IM

Table 1. Induction Motor Parameters

Parameter’s name | Values of Parameters | Rated Variable | Rated Values |

• Stator resistance  | 11.8 Ω | Rated voltage | 380 V |

• Rotor resistance  | 11.3085 Ω | Rated current | 2.2 A |

• Mutual cyclic inductance  | 0.5400 H | Rated power | 1.1 kW |

• Stator cyclic inductance  | 0.5578 H | Rated frequency | 50 Hz |

• Rotor cyclic inductance  | 0.6152 H | Rated speed | 1430 rpm |

• Moment of inertia  | 0.0020 Kg.m2 | Base angular frequency | 314.16 rad/s |

• Friction coefficient  | 3.1165e-004  | Synchronous speed | 314.16 rad/s |

• Number of pair poles  | 1 | Core (Iron) loss resistance | 750–900 Ω |

Figure 5 presents the experimental results obtained using the proposed adaptive neural controller, where the DC-link voltage  was set to 380 V. The motor was subjected to a triangular speed reversal profile ranging from +150 rad/s to –150 rad/s. The results clearly demonstrate the controller’s effectiveness in tracking both high and low-speed commands while maintaining robust performance in the presence of parameter uncertainties (including variations in rotor resistance ±10% nominal, stator inductance, and load torque disturbances).

was set to 380 V. The motor was subjected to a triangular speed reversal profile ranging from +150 rad/s to –150 rad/s. The results clearly demonstrate the controller’s effectiveness in tracking both high and low-speed commands while maintaining robust performance in the presence of parameter uncertainties (including variations in rotor resistance ±10% nominal, stator inductance, and load torque disturbances).

Figure 5. Performance and accuracy of the proposed control scheme under speed reversal and load variations

- Motor Speed and Electromagnetic Torque: The top two subplots in Figure 5 illustrate the rotor speed response and electromagnetic torque under a triangular speed reference profile ranging from

to

to  over 1 second. The proposed adaptive neural controller ensures that the motor speed closely tracks its reference with high precision. The maximum overshoot does not exceed

over 1 second. The proposed adaptive neural controller ensures that the motor speed closely tracks its reference with high precision. The maximum overshoot does not exceed  (1.85%), while the settling time remains below

(1.85%), while the settling time remains below  , reflecting rapid adaptation. The torque response demonstrates three distinct transitions: from

, reflecting rapid adaptation. The torque response demonstrates three distinct transitions: from  to

to  at

at  , then to

, then to  at

at  , and finally back to

, and finally back to  at

at  , with rise times of less than

, with rise times of less than  and torque ripple bounded within

and torque ripple bounded within  . These results validate the controller’s fast torque regulation and robustness under dynamic loading.

. These results validate the controller’s fast torque regulation and robustness under dynamic loading. - Speed Error: The third subplot shows the instantaneous speed error over time. Throughout the full operation, the error remains confined within

, with an average RMS error of approximately

, with an average RMS error of approximately  . Even during abrupt speed reversals and torque transitions, the peak deviation does not exceed

. Even during abrupt speed reversals and torque transitions, the peak deviation does not exceed  , demonstrating excellent tracking capability. This tight error band underscores the controller’s ability to reject disturbances and compensate for model uncertainties, such as rotor resistance mismatches (

, demonstrating excellent tracking capability. This tight error band underscores the controller’s ability to reject disturbances and compensate for model uncertainties, such as rotor resistance mismatches ( ) and unmodeled dynamics like friction (

) and unmodeled dynamics like friction ( ). The controller's fast response dynamics allow for immediate correction, even under rapidly changing conditions.

). The controller's fast response dynamics allow for immediate correction, even under rapidly changing conditions. - Stator Currents in αβ Frame: The fourth subplot displays the

stator current waveforms during the control process. The currents exhibit smooth, sinusoidal shapes with modulation that reflects the system’s torque and speed demands. Peak amplitudes reach

stator current waveforms during the control process. The currents exhibit smooth, sinusoidal shapes with modulation that reflects the system’s torque and speed demands. Peak amplitudes reach  during torque transitions, while they fall to

during torque transitions, while they fall to  during near-zero torque intervals. The symmetry and 90° phase shift between the

during near-zero torque intervals. The symmetry and 90° phase shift between the  and

and  components confirm proper vector control in the stator reference frame. No current clipping or imbalance is observed, indicating that the controller effectively regulates stator flux under varying speed and torque conditions. Moreover, the observed current profiles suggest a total harmonic distortion (THD) of less than

components confirm proper vector control in the stator reference frame. No current clipping or imbalance is observed, indicating that the controller effectively regulates stator flux under varying speed and torque conditions. Moreover, the observed current profiles suggest a total harmonic distortion (THD) of less than  , supporting the quality of the voltage generation (THD estimated from FFT analysis as per IEEE Std 519).

, supporting the quality of the voltage generation (THD estimated from FFT analysis as per IEEE Std 519). - Stator Voltages in αβ Frame: Finally, the bottom plot shows the corresponding αβ stator voltages, which also maintain clean sinusoidal patterns throughout the operation. Voltage amplitudes dynamically adjust from

during steady-state conditions to

during steady-state conditions to  under rapid acceleration or deceleration phases. These waveforms demonstrate that the controller successfully modulates the voltage through the VSI to meet real-time torque demands. The absence of voltage saturation or distortion confirms that the control algorithm maintains effective regulation even under high dynamic load. The alignment between stator currents and voltages indicates proper field orientation, ensuring efficient torque production and robust system behavior under sensorless conditions.

under rapid acceleration or deceleration phases. These waveforms demonstrate that the controller successfully modulates the voltage through the VSI to meet real-time torque demands. The absence of voltage saturation or distortion confirms that the control algorithm maintains effective regulation even under high dynamic load. The alignment between stator currents and voltages indicates proper field orientation, ensuring efficient torque production and robust system behavior under sensorless conditions.

Comparative Study and Robustness Assessment

To assess the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed control algorithm, a comparative analysis is conducted against several relevant state-of-the-art methods cited in the literature [5]-[11], [26]-[38] and [47]. Table 2 highlights a selection of representative studies used for benchmarking. Among them, [3] exhibits relatively acceptable performance with a low flux ripple, fast transient response  , and constant switching frequency. However, most of the other references demonstrate limited performance, primarily due to variable switching frequencies and insufficient torque generation beyond critical thresholds. For instance, [5] and [26] suffer from high torque ripple and slow transients (

, and constant switching frequency. However, most of the other references demonstrate limited performance, primarily due to variable switching frequencies and insufficient torque generation beyond critical thresholds. For instance, [5] and [26] suffer from high torque ripple and slow transients ( and

and  , respectively), while [7] shows noisy steady-state behavior and lacks switching frequency control. Reference [11] offers a moderate torque response but uses a non-uniform frequency, and [34] exhibits a high torque ripple with a non-constant frequency. Although [29] employs constant switching, its torque response is slow (

, respectively), while [7] shows noisy steady-state behavior and lacks switching frequency control. Reference [11] offers a moderate torque response but uses a non-uniform frequency, and [34] exhibits a high torque ripple with a non-constant frequency. Although [29] employs constant switching, its torque response is slow ( ) and lacks high torque capability. Overall, the proposed algorithm demonstrates clear advantages in terms of reduced flux and torque ripples, improved transient and steady-state behavior, constant switching frequency

) and lacks high torque capability. Overall, the proposed algorithm demonstrates clear advantages in terms of reduced flux and torque ripples, improved transient and steady-state behavior, constant switching frequency  , and enhanced torque production, providing a notable improvement over previously published method.

, and enhanced torque production, providing a notable improvement over previously published method.

Table 2. Evaluation of the Proposed Control Scheme Against Literature Methods (Comparative Study)

| Flux Ripples | Transient State Response for  | Steady State Response for  | High Torque Production | Switching Frequency |

Proposed | Very Low | 0.65 ms | Lower | Yes | Constant |

Ref. [3] | Low | 1.50 ms | Low | Yes | Constant |

Ref. [5] | High | 4.60 ms | High | No | Variable |

Ref. [7] | Not shown | 10.2 ms | Acceptable (noisy) | No | Variable |

Ref. [11] | High | 1.00 ms | Moderate | No | Non-uniform |

Ref. [26] | High | 10.0 ms | High (slow recovery) | No | Variable |

Ref. [29] | Low | 9.50 ms | Acceptable | No | Constant |

Ref. [34] | High | 5.20 ms | High | No | Non-constant |

Ref. [47] | Low | 16.0 ms | Low | No | Variable |

For further clarification of the effectiveness of the proposed control scheme, a numerical comparison is presented in Figure 6, focusing on flux ripples, torque ripples, and torque response time during torque step regulation (TSR). As shown in Figure 6 (left), the proposed adaptive neural controller achieves the lowest stator flux ripple, measured at 0.002 Wb, outperforming conventional direct torque-stator-flux control (DTSFC) and direct torque-rotor-flux control (DTRFC) strategies. Similarly, Figure 6 (middle) illustrates that the proposed method significantly reduces torque ripple to 0.043 N·m (this corresponds to <0.5% of rated torque (9.1 N·m)), indicating superior torque smoothness under dynamic conditions. Moreover, Figure 6 (right) confirms that the proposed technique exhibits the fastest torque response time of 0.65 ms, compared to FOC, DTSFC, and DTRFC approaches, highlighting its enhanced dynamic capability and responsiveness.

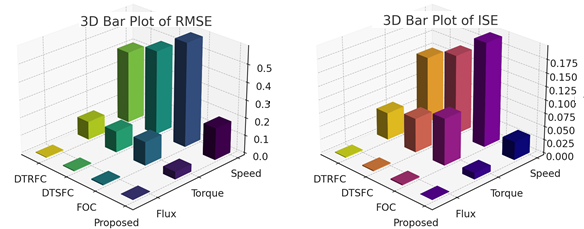

To evaluate the proposed control strategy for induction motor drives, we employ key performance indices, including settling time, root mean squared error (RMSE), and integral of squared error (ISE). These indices provide a clear basis for quantitative comparison with established methods such as FOC, DTSFC, and DTRFC, as detailed in Table 3, where the best results are marked in bold. The proposed controller demonstrates notably shorter settling times, reflecting its ability to deliver fast dynamic response and convergence. Furthermore, the RMSE and ISE values consistently indicate improved tracking accuracy during both transient and steady-state conditions (e.g., 78% lower RMSE compared to others). To support these findings, the RMSE and ISE results are also presented in Figure 7 for visual interpretation.

Figure 6. Comparative Analysis of Dynamic and Steady-State Metrics for Competing Strategies

Table 3. Analysis of performance indices (Comparative Study)

| Settling time (ms) | RMSE | ISE |

Speed | Torque | Flux | Speed | Torque | Flux | Speed | Torque | Flux |

Proposed | 25 | 0.65 | 14 | 0.18 | 0.043 | 0.0020 | 0.034 | 0.012 | 0.0004 |

FOC | 82 | 1.80 | 33 | 0.59 | 0.134 | 0.0057 | 0.196 | 0.088 | 0.0021 |

DTSFC | 72 | 1.35 | 29 | 0.48 | 0.119 | 0.0044 | 0.151 | 0.064 | 0.0017 |

DTRFC | 64 | 1.25 | 25 | 0.41 | 0.103 | 0.0032 | 0.126 | 0.051 | 0.0012 |

Figure 7. Comparative Analysis of Performance indices (a) RMSE and (b) ISE

The results presented in Table 3 and visualized in the 3D bar plots clearly highlight the superior performance of the proposed adaptive control strategy. In terms of settling time, the proposed method achieves the fastest convergence for speed, torque, and flux, significantly outperforming FOC, DTSFC, and DTRFC. The 3D RMSE and ISE plots provide a visual confirmation of this improvement, showing consistently lower error values across all control variables. Specifically, the proposed controller yields the lowest RMSE and ISE in torque and flux, indicating precise and smooth regulation. The bar plots also emphasize the performance gap between the proposed approach and the conventional methods, reinforcing its enhanced dynamic response and error minimization capabilities. Overall, the proposed strategy demonstrates a clear advantage in both transient behavior and steady-state accuracy. While tuning parameters such as the learning rate  and number of neurons

and number of neurons  can influence tracking performance, our empirical tests showed robustness to moderate variations. Formal sensitivity analysis will be considered in future work.

can influence tracking performance, our empirical tests showed robustness to moderate variations. Formal sensitivity analysis will be considered in future work.

- CONCLUSIONS

This study has established a new adaptive flux-oriented control framework for sensorless induction motor drives, effectively integrating online neural network learning within the MRAS structure. The proposed methodology demonstrates superior transient and steady-state performance, as substantiated by rigorous quantitative metrics, including RMSE, ISE, flux and torque ripple, and dynamic response times (91% reduction in steady-state speed error and a 78% improvement in RMSE compared to the recent strategies, 0.65 ms torque response, 0.043 Nm torque ripple, and flux ripple of 0.002 Wb). The experimental validation confirms the controller’s robustness under challenging conditions, such as rapid speed reversals and load disturbances, while maintaining constant switching frequency and precise vector alignment.

Beyond the performance enhancements, the work contributes a scalable and computationally feasible architecture for real-time control, leveraging neural adaptation without compromising system responsiveness or stability. These findings are particularly relevant for advanced industrial applications requiring high dynamic performance, including robotics, electric vehicles, and aerospace actuation systems. The experimental findings validate the real-time feasibility and accuracy of the proposed method under practical conditions. Nonetheless, some performance limits may emerge under extreme transients or high-noise environments. The maintained constant switching frequency and its implications for harmonic distortion and energy loss will be explored in future work. Looking forward, further research may explore the integration of deep neural networks or hybrid neuro-symbolic models to capture unmodeled nonlinearities more effectively, particularly under severe parameter variations or temperature-dependent dynamics. In addition, extending the framework to multi-phase or multi-motor systems and embedding it within predictive control or reinforcement learning paradigms could provide enhanced fault tolerance and optimality in complex environments. Finally, formal treatment of stability under bounded approximation errors and measurement uncertainties remains an important direction to support certification in safety-critical applications.

DECLARATION

Author Contribution

All authors contributed equally to the main contributor to this paper.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- A. Bennassar, A. Abbou, and M. Akherraz, “Combining fuzzy Luenberger observer and Kalman filter for speed sensorless integral backstepping controlled induction motor drive,” International Journal of Automation and Control, vol. 11, no. 3, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1504/IJAAC.2017.084871.

- A. Rihar et al., “Emerging Technologies for Advanced Power Electronics and Machine Design in Electric Drives,” Applied Sciences, vol. 14, no. 24, p. 11559, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/app142411559.

- F. Shiravani, P. Alkorta, J. A. Cortajarena, and O. Barambones, “An Enhanced Sliding Mode Speed Control for Induction Motor Drives,” Actuators, vol. 11, no. 1, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/act11010018.

- P. M. Menghal and A. J. Laxmi, “Neural network based dynamic simulation of induction motor drive,” in 2013 International Conference on Power, Energy and Control (ICPEC), pp. 566–571, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICPEC.2013.6527722.

- U. Sengamalai, G. Anbazhagan, T. M. Thamizh Thentral, P. Vishnuram, T. Khurshaid, and S. Kamel, “Three Phase Induction Motor Drive: A Systematic Review on Dynamic Modeling, Parameter Estimation, and Control Schemes,” Energies, vol. 15, no. 21, p. 8260, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15218260.

- H. Kubota, K. Matsuse, and T. Nakano, “DSP-Based Speed Adaptive Flux Observer of Induction Motor,” IEEE Trans Ind Appl, vol. 29, no. 2, 1993, https://doi.org/10.1109/28.216542.

- N. Medjadjii, A. Chaker, and D. M. Medjahed, “Quality improvement of speed estimation in induction motor drive by using fuzzy-MRAS observer with experimental investigation,” International Review of Automatic Control, vol. 11, no. 1, 2018, https://doi.org/10.15866/ireaco.v11i1.14425.

- Q. Sun, Y. Zhang, S. Wu, C. Zhang, and X. Wang, “Adaptive Robust Control of an Industrial Motor-Driven Stage with Disturbance Rejection Ability Based on Multidimensional Taylor Network,” Applied Sciences (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 22, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/app132212231.

- X. Liu, S. Zhen, F. Wang, and M. Li, “Adaptive robust control of the PMSM servo system with servo and performance constraints,” Journal of Vibration and Control, p. 10775463241278003, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1177/10775463241278003.

- Z. Mekrini and B. Seddik, “Fuzzy logic application for intelligent control of an asynchronous machine,” Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, vol. 7, no. 1, 2017, https://doi.org/10.11591/ijeecs.v7.i1.

- W. Hamdi, M. Y. Hammoudi, and A. Betka, “Sensorless Speed Control of Induction Motor Using Model Reference Adaptive System and Deadbeat Regulator,” Engineering Proceedings, vol. 56, no. 1, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/ASEC2023-15240.

- K. N. Sujatha and K. Vaisakh, “Implementation of Adaptive Neuro Fuzzy Inference System in Speed Control of Induction Motor Drives,” Journal of Intelligent Learning Systems and Applications, vol. 02, no. 02, 2010, https://doi.org/10.4236/jilsa.2010.22014.

- P. Stewart, D. A. Stone, and P. J. Fleming, “Design of robust fuzzy-logic control systems by multi-objective evolutionary methods with hardware in the loop,” Eng Appl Artif Intell, vol. 17, no. 3, 2004, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2004.03.003.

- T. Takagi and M. Sugeno, “Fuzzy Identification of Systems and Its Applications to Modeling and Control,” IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern, vol. SMC-15, no. 1, 1985, https://doi.org/10.1109/TSMC.1985.6313399.

- B. Bekhiti, B. Nail, I. E. Tibermacine, and R. Salim, “On Hyper‐Stability Theory Based Multivariable Nonlinear Adaptive Control: Experimental Validation on Induction Motors,” IET Electr Power Appl, vol. 19, no. 1, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1049/elp2.70035.

- B. Bekhiti, B. Nail, and A. Kouzou, “Adaptive senssorless control of a feedback linearized induction motor via the extended kalman filter,” In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Power Electronics and Their Applications (ICPEA'15), 2015, https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Belkacem-Bekhiti/publication/274566711_Adaptive_Sensorless_Control_of_a_Feedback_Linearised_Induction_Motor_via_Extended_Kalman_Filter/.

- B. Bekhiti, A. Dahimene, and K. Hariche, Advanced nonlinear control and state observation in robotics. Scholars’ Press, Igors Ivanovs, 2017, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314114908_Advanced_nonlinear_control_and_state_observation_in_robotics.

- A. A. Mostfa, N. A. Zakar, R. Raad Al-Mola, and A.-N. Sharkawy, “Enhancing Wind Turbine Power Output Estimation Using Causal Inference and Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System ANFIS,” Kufa Journal of Engineering, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 400–422, Apr. 2025, https://doi.org/10.30572/2018/KJE/160224.

- I. A. Kheioon, R. Al-Sabur, and A.-N. Sharkawy, “Design and Modeling of an Intelligent Robotic Gripper Using a Cam Mechanism with Position and Force Control Using an Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Computing Technique,” Automation, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 4, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6010004.

- A. S. Bahedh, I. A. Kheioon, B. S. Munahi and R. Al-Sabur, "Modelling and controlling of modified robotic gripper mechanism using intelligent technique scheme," 2022 Iraqi International Conference on Communication and Information Technologies (IICCIT), pp. 252-257, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/IICCIT55816.2022.10010666.

- D. D. Saputra, A. Ma, H. Maghfiroh, M. A. Baballe, and A. Marcelo, “Performance Evaluation of Sliding Mode Control ( SMC ) for DC Motor Speed Control,” Jurnal Ilmiah Teknik Elektro Komputer dan Informatika (JITEKI), vol. 9, no. 2, 2023, https://doi.org/10.26555/jiteki.v9i2.26291.

- M. H. Sabzalian et al., “A Neural Controller for Induction Motors: Fractional-Order Stability Analysis and Online Learning Algorithm,” Mathematics, vol. 10, no. 6, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/math10061003.

- M. A. Denaï and S. A. Attia, “Intelligent Control of an Induction Motor,” Electric Power Components and Systems, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 409–427, 2002, https://doi.org/10.1080/15325000252888010.

- N. Pimkumwong and M. S. Wang, “Online speed estimation using artificial neural network for speed sensorless direct torque control of induction motor based on constant V/F control technique,” Energies (Basel), vol. 11, no. 8, 2018, https://doi.org/10.3390/en11082176.

- A. A. Bohari, W. M. Utomo, Z. A. Haron, N. Muhd. Zin, S. Y. Sim, and R. M. Ariff, “Speed Tracking of Indirect Field Oriented Control Induction Motor Using Neural Network,” Procedia Technology, vol. 11, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.protcy.2013.12.173.

- M. Demirtas, E. Ilten, and H. Calgan, “Pareto-Based Multi-objective Optimization for Fractional Order PI λ Speed Control of Induction Motor by Using Elman Neural Network,” Arab J Sci Eng, vol. 44, no. 3, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-018-3364-2.

- P. Brandstetter and M. Kuchar, “Sensorless control of variable speed induction motor drive using RBF neural network,” Journal of Applied Logic, vol. 24, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jal.2016.11.017.

- H. Saleeb, R. Kassem, “Artificial neural networks applied on induction motor drive for an electric vehicle propulsion system,” Electrical Engineering, vol. 104, no. 3, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00202-021-01418-y.

- H. Acikgoz, “Real-time adaptive speed control of vector-controlled induction motor drive based on online-trained Type-2 Fuzzy Neural Network Controller,” International Transactions on Electrical Energy Systems, vol. 30, no. 12, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1002/2050-7038.12678.

- A. B. Sharma, S. Tiwari and B. Singh, "Intelligent Speed Estimation in Induction Motor Drive Control using Feed - Forward Neural Network Assisted Model Reference Adaptive System," 2020 IEEE Students Conference on Engineering & Systems (SCES), pp. 1-6, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1109/SCES50439.2020.9236736.

- S. Hussain and M. A. Bazaz, “Adaptive neural type II fuzzy logic-based speed control of induction motor drive,” in Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, pp. 81-92, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-7386-1_7.

- M. H. Sabzalian, A. Mohammadzadeh, S. Lin, and W. Zhang, “New approach to control the induction motors based on immersion and invariance technique,” IET Control Theory and Applications, vol. 13, no. 10, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-cta.2018.5026.

- R. Kumar, S. Das, P. Syam, and A. K. Chattopadhyay, “Review on model reference adaptive system for sensorless vector control of induction motor drives,” IET Electr Power Appl, vol. 9, no. 7, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-epa.2014.0220.

- Y. Ren, R. Wang, S. J. Rind, P. Zeng, and L. Jiang, “Speed sensorless nonlinear adaptive control of induction motor using combined speed and perturbation observer,” Control Eng Pract, vol. 123, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conengprac.2022.105166.

- J. C. Travieso-Torres and M. A. Duarte-Mermoud, “Normalized Model Reference Adaptive Control Applied to High Starting Torque Scalar Control Scheme for Induction Motors,” Energies (Basel), vol. 15, no. 10, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/en15103606.

- I. D. Mienye, T. G. Swart, and G. Obaido, “Recurrent Neural Networks: A Comprehensive Review of Architectures, Variants, and Applications,” Information, vol. 15, no. 9, p. 517, Aug. 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/info15090517.

- V. S. Lalapura, V. R. Bhimavarapu, J. Amudha, and H. S. Satheesh, “A Systematic Evaluation of Recurrent Neural Network Models for Edge Intelligence and Human Activity Recognition Applications,” Algorithms, vol. 17, no. 3, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/a17030104.

- X. Wu, B. Xiang, H. Lu, C. Li, X. Huang, and W. Huang, “Optimizing Recurrent Neural Networks: A Study on Gradient Normalization of Weights for Enhanced Training Efficiency,” Applied Sciences, vol. 14, no. 15, p. 6578, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/app14156578.

- G. C. Verghese and S. R. Sanders, “Observers For Flux Estimation In Induction Machines,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 35, no. 1, 1988, https://doi.org/10.1109/41.3067.

- A. De Luca and G. Ulivi, “Dynamic decoupling of voltage frequency controlled induction motors,” pp. 127–137, 1988, https://doi.org/10.1007/BFb0042208.

- H. Xie, F. Wang, W. Zhang, C. Garcia, J. Rodríguez and R. Kennel, "Sliding Mode Flux Observer Based Predictive Field Oriented Control for Induction Machine Drives," 2020 IEEE 9th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference (IPEMC2020-ECCE Asia), pp. 3021-3025, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/IPEMC-ECCEAsia48364.2020.9368086.

- A. G. Zinyagin, A. V. Muntin, V. S. Tynchenko, P. I. Zhikharev, N. R. Borisenko, and I. Malashin, “Recurrent Neural Network (RNN)-Based Approach to Predict Mean Flow Stress in Industrial Rolling,” Metals (2075-4701), vol. 14, no. 12, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/met14121329.

- C. H. Yu, et al., “Recurrent neural network methods for extracting dynamic balance variables during gait from a single inertial measurement unit,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 22, p. 9040, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/s23229040.

- D. Utebayeva, L. Ilipbayeva, and E. T. Matson, “Practical study of recurrent neural networks for efficient real-time drone sound detection: A review,” Drones, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 26, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/drones7010026.

- R. Pascual, M. Esteban, J. M. Guerrero, and C. A. Platero, “Recurrent Neuronal Networks for the Prediction of the Temperature of a Synchronous Machine During Its Operation,” Machines, vol. 13, no. 5, p. 387, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13050387.

- A. J. Abougarair, M. K. Aburakhis, and M. M. Edardar, “Adaptive neural networks based robust output feedback controllers for nonlinear systems,” International Journal of Robotics and Control Systems, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 37-56, 2022, https://doi.org/10.31763/ijrcs.v2i1.523.

- N. T. Pham, and P. D. Nguyen, “A Novel Hybrid Backstepping and Fuzzy Control for Three Phase Induction Motor Drivers,” International Journal of Robotics & Control Systems, vol. 5, no. 1, 2025, https://doi.org/10.31763/ijrcs.v5i1.1707.

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

| Belkacem Bekhiti, is a professor at the Institute of Aeronautics and Space Studies, Blida University, Algeria. He earned his Ph.D. in Electrical Engineering from Boumerdes University in 2018, with a focus on control theory and automation. His research bridges advanced control systems and aerospace engineering, with interests in MIMO control, system identification, and model order reduction. Dr. Bekhiti has authored numerous publications and books, and he actively mentors graduate students in aerospace and control disciplines. With over a decade of experience in the aerospace industry, including work with the Algerian Air Agency, he continues to contribute to both academic and industrial advancements through national and international collaborations. |

|

|

| Raheem Al-Sabur, received his Ph.D. in Mechanical Engineering with a specialization in friction stir welding. He is a member of both the American Welding Society (AWS) and the German Welding Society (DVS). Since 2002, he has been serving as a faculty member in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Basrah, Iraq. With nearly two decades of academic and teaching experience, Dr. Al-Sabur has developed expertise across a range of mechanical engineering domains, particularly in welding technologies. His research and instructional interests include fusion and solid-state welding processes, welding defects and inspection, as well as both destructive and non-destructive testing methods. He also possesses practical experience in computational tools and optimization techniques, including the use of Minitab, neural networks, and image-based analysis for engineering applications. |

|

|

| Abdel-Nasser Sharkawy, is an associate Professor at Mechatronics Engineering, Mechanical Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, South Valley University (SVU), Qena, Egypt. He was graduated with a first-class honors B.Sc. degree in May 2013 and received his M.Sc. degree in April 2016 from Mechatronics Engineering, Mechanical Engineering Department, SVU, Egypt. In March 2020, he received his Ph.D. degree from Robotics Group, Department of Mechanical Engineering and Aeronautics, University of Patras, Patras, Greece. His PhD was about “Intelligent Control and Impedance Adjustment for Efficient Human-Robot Cooperation”. He has an excellent experience for teaching the under-graduate and postgraduate courses in the field of Mechatronics and Robotics Engineering. Sharkawy has published more than 75 papers in international scientific journals, book chapters and international scientific conferences. He serves as reviewer for about 50 journals and 10 conferences. His research areas of interest include robotics, human-robot interaction, mechatronic systems, neural networks, machine learning, and control and automation. |

Belkacem Bekhiti (A New Adaptive Flux-Oriented Control Framework for Induction Motors with Online Neural Network Training)