ISSN: 2685-9572 Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro

Vol. 7, No. 4, December 2025, pp. 842-857

Geographic-Origin Music Classification from Numerical Audio Features: Integrating Unsupervised Clustering with Supervised Models

Andri Pranolo 1, Sularso Sularso 2, Nuril Anwar 1, Agung Bella Utama Putra 3,

Aji Prasetya Wibawa 3, Shoffan Saifullah 4,5, Rafał Dreżewski 5, Zalik Nuryana 6, Tri Andi 7

1 Informatics Department, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

2 Elementary Teacher Education, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

3 Electrical Engineering and Informatics, Universitas Negeri Malang, Malang, Indonesia

4 Department of Informatics, Universitas Pembangunan Nasional Veteran Yogyakarta, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

5 Faculty of Computer Science, AGH University of Krakow, Krakow, Poland

6 Association for Scientific Computing Electronics and Engineering (ASCEE), Education Society, Indonesia

7 Information Technology, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 31 May 2025 Revised 06 November 2025 Accepted 19 November 2025 |

|

Classifying the geographic origin of music is a relevant task in music information retrieval, yet most studies have focused on genre or style recognition rather than regional origin. This study evaluates Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) models on the UCI Geographical Origin of Music dataset (1,059 tracks from 33 non-Western regions) using numerical audio features. To incorporate latent structure, we first applied K-means clustering with the optimal number of clusters ( ) determined by the Elbow and Silhouette methods. The cluster assignments were used as auxiliary signals for training, while evaluation relied on the true region labels. Classification performance was assessed with Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score. Results show that SVM achieved 99.53% accuracy (95% CI: 97.38–99.92%), while CNN reached 98.58% accuracy (95% CI: 95.92–99.52%); Precision, Recall, and F1 mirrored these values. The differences confirm SVM’s superior performance on this dataset, though the near-perfect scores also suggest strong separability in the feature space and potential risks of overfitting. Learning-curve analysis indicated stable training, and cluster supervision provided small but consistent benefits. Overall, SVM remains a reliable baseline for tabular music features, while CNNs may require spectro-temporal representations to leverage their full potential. Future work should validate these findings across multiple datasets, apply cross-validation with statistical significance testing, and explore hybrid deep models for broader generalization. ) determined by the Elbow and Silhouette methods. The cluster assignments were used as auxiliary signals for training, while evaluation relied on the true region labels. Classification performance was assessed with Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score. Results show that SVM achieved 99.53% accuracy (95% CI: 97.38–99.92%), while CNN reached 98.58% accuracy (95% CI: 95.92–99.52%); Precision, Recall, and F1 mirrored these values. The differences confirm SVM’s superior performance on this dataset, though the near-perfect scores also suggest strong separability in the feature space and potential risks of overfitting. Learning-curve analysis indicated stable training, and cluster supervision provided small but consistent benefits. Overall, SVM remains a reliable baseline for tabular music features, while CNNs may require spectro-temporal representations to leverage their full potential. Future work should validate these findings across multiple datasets, apply cross-validation with statistical significance testing, and explore hybrid deep models for broader generalization. |

Keywords: Geographical Music; Music Information Retrieval; K-means Clustering; Cluster-Supervised Learning; Support Vector Machine; Convolutional Neural Network; Classification |

Corresponding Author: Andri Pranolo, Informatics Department, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Email: andri.pranolo@tif.uad.ac.id |

This work is open access under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: A. Pranolo, S. Sularso, N. Anwar, A. B. U. Putra, A. P. Wibawa, S. Saifullah, R. Dreżewski, Z. Nuryana, and T. Andi, “Geographic-Origin Music Classification from Numerical Audio Features: Integrating Unsupervised Clustering with Supervised Models,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 842-857, 2025, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v7i4.13400. |

INTRODUCTION

The advancement of information technology (IT) and artificial intelligence (AI) has profoundly impacted a range of sectors [1]–[3], from healthcare and finance to marketing and transportation [4]. One of the key challenges is effectively processing and analyzing large, diverse datasets, which can vary greatly in terms of structure and content [5]. Techniques such as clustering [6], which groups similar data points, and classification [7]–[9], which assigns labels based on patterns within the data, are essential for supporting informed decision-making in these domains.

Clustering methods such as K-Means [10], Agglomerative Clustering [11], and DBSCAN [12] are popular algorithms often used in data clustering. Among these methods, K-Means is the most commonly used method because it has advantages in simple implementation, high computational efficiency, and clear grouping results [13]. However, K-Means requires precisely determining the optimal number of clusters (k) so that the grouping results can produce useful information [14]. Several evaluation techniques are often used to determine the optimal number of clusters, such as the elbow method, which relies on inertial value analysis, and the silhouette score, which evaluates the quality of inter-cluster separation [15]. Combining these two methods effectively provides accurate decisions about the best number of clusters to use.

Once the clustering stage is complete, the next step is to classify the data based on the resulting cluster labels. Classification methods such as Support Vector Machine (SVM) [16][17], multi-layer perceptron (MLP) [18], SMOTE [19], XGBoost [20][21], LSTM [22], and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) [23], have become popular because they have been shown to produce high performance in various previous studies [24]. SVM is known to be a highly effective method for data that has linear or near-linear separable characteristics [25]. In contrast, CNN is known to be more effective in handling complex data, particularly data with strong spatial patterns [26].

In the music information retrieval (MIR) domain, these techniques have been widely applied. MIR has advanced rapidly with the rise of artificial intelligence [27][28], enabling applications such as genre recognition, mood detection, and recommendation systems [29]–[31]. Beyond these popular tasks, classifying the geographic origin of music emerges as an important research direction with implications for cultural heritage preservation, recommendation, and cross-cultural analysis [32]. Unlike genre classification, however, origin classification is more subtle, since musical styles often overlap across regions and are influenced by cultural exchanges [33].

Most prior work has focused on genre classification using deep learning models trained on spectrograms, where CNNs have shown strong performance in capturing spatial patterns in time–frequency representations [34]–[36]. Other studies have applied SVMs and classical machine learning models to tabular audio descriptors, reporting competitive results in limited scenarios [37]. However, geographic origin classification remains underexplored, particularly when relying solely on numerical features rather than spectrograms. Moreover, the potential of unsupervised cluster structures to provide auxiliary training signals in supervised classification has not been systematically investigated.

The research contribution is fourfold: (i) we formalize cluster-supervised learning for this task, where unsupervised K-means provides auxiliary pseudo-labels to shape decision boundaries while evaluation uses only the true origin labels; (ii) we establish a validation-rigorous benchmark on the UCI Geographical Origin of Music dataset, using stratified cross-validation, nested hyperparameter tuning, and learning curves to address pitfalls of single-split reports; (iii) we compare SVM (RBF) with a tabular-appropriate compact CNN/MLP and classical baselines, including ablations with and without cluster supervision, scaling, and PCA; and (iv) we report statistical significance and uncertainty estimates (95% confidence intervals) and analyze risks of overfitting. Together, these contributions fill a gap in MIR research and provide a reproducible framework for future work in music origin classification.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews related work on clustering and classification methods in music information retrieval. Section 3 describes the proposed methodology, including preprocessing, clustering, and classification models. Section 4 presents the experimental setup and evaluation metrics, while Section 5 reports and discusses the results, including ablation studies and statistical analyses. Section 6 concludes the paper with a summary of findings, limitations, and directions for future research.

RELATED WORKS

Clustering in Music Information Retrieval

Clustering is a foundational unsupervised learning technique widely applied in data mining and machine learning [38]. In the context of music information retrieval (MIR), clustering is often used to group tracks according to shared acoustic or statistical features such as timbre, tempo, or rhythmic patterns [39][40]. Algorithms such as K-means [41], Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering [42], and DBSCAN [43] are particularly prominent. Among these, K-means remains the most frequently adopted due to its simplicity, interpretability, and computational efficiency [44]. However, its effectiveness depends on choosing the appropriate number of clusters ( ), for which criteria such as the Elbow method and Silhouette coefficient are commonly applied.

), for which criteria such as the Elbow method and Silhouette coefficient are commonly applied.

In MIR tasks, clustering has been employed in genre grouping, playlist generation, and audio similarity analysis [33]. For example, clustering combined with feature selection has been used to automatically categorize songs into genre-like groupings [45]. Nevertheless, in the specific case of geographic-origin classification, the use of clustering is still limited. Existing works have mostly relied on clustering as a pre-processing or exploratory step rather than integrating cluster information into supervised models [46]. This gap provides a strong motivation for exploring whether cluster-informed supervision can enhance the classification of music origin.

Classification in Music Information Retrieval

Classification methods are central to MIR, particularly for tasks such as genre recognition, mood prediction, instrument detection, and artist identification [28],[47]. In recent years, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have been dominant in MIR, primarily applied to spectrograms or time–frequency representations of audio signals. CNNs are well-suited to this modality because they can automatically learn hierarchical spatial patterns from spectrogram images [48]. For instance, Seo (2024) presented a comprehensive comparison of CNN architectures for genre recognition using multispectral features, demonstrating CNNs’ superiority in capturing spectral correlations [36]. Similarly, Ding et al. (2024) proposed an ECAS-CNN architecture incorporating attention mechanisms for Mel-spectrograms, achieving state-of-the-art performance in genre classification [49]. These studies highlight that CNNs are highly effective when the input is structured in a two-dimensional, image-like form.

On the other hand, Support Vector Machines (SVMs) and other traditional classifiers remain competitive for tabular or numerical audio descriptors. Such features typically include timbre (MFCCs), rhythm, tempo, or chroma statistics. Liang et al. (2023) emphasized that SVMs, when applied to handcrafted descriptors, can achieve performance comparable to that of deep models under certain conditions [50]. The advantage of SVM lies in its ability to construct robust decision boundaries in relatively low-dimensional spaces, particularly when the data is not extremely large. This makes SVMs attractive for scenarios where spectrogram representations are unavailable or where computational simplicity is desired. Thus, while CNNs dominate spectrogram-based tasks, SVMs remain relevant in feature-based MIR, underscoring the need to evaluate their comparative effectiveness for problems such as geographic origin classification.

Geographic-Origin Music Classification

The task of geographic-origin classification is relatively underexplored compared to genre or mood classification. The UCI Geographical Origin of Music dataset [51] has emerged as the standard benchmark for this problem. It contains 1,059 music tracks from 33 non-Western regions, represented by numerical descriptors, and explicitly excludes Western music to focus on culturally distinct styles. Zhou et al. (2014) investigated this dataset in a CMU technical report, applying standard classifiers but with limited evaluation depth [52][53]. More recently, Kostrzewa et al. (2024) revisited the dataset and explored different classification strategies, reporting promising results but again with restricted methodological rigor [54][55].

These studies highlight two key limitations: (i) the reliance on a single dataset without cross-validation or significance testing, and (ii) the absence of frameworks that combine unsupervised clustering with supervised classification. As a result, claims of performance superiority remain difficult to generalize. Our work seeks to address these gaps by adopting rigorous evaluation protocols (stratified cross-validation, nested tuning, confidence intervals) and by proposing a cluster-supervised framework that systematically integrates K-means clustering with supervised classifiers.

Hybrid Clustering–Classification and Pseudo-Labeling

Beyond MIR, hybrid approaches that combine clustering and classification have gained traction in machine learning [56][57]. These methods leverage unsupervised cluster structure as auxiliary information to guide supervised models [58]. Enguehard et al. (2019) provided a survey of semi-supervised approaches that exploit clustering to regularize classification, showing improved generalization when labeled data is scarce [59]. Similarly, Gupta et al. (2020) proposed a pseudo-labeling framework where cluster assignments are treated as weak labels during training, demonstrating effectiveness in stabilizing learning across domains [60], [61].

In the context of MIR, however, such hybrid methods have rarely been applied. While clustering has been used for exploratory analysis and classification for genre and mood prediction, its integration for music origin classification has not been systematically investigated. By introducing cluster-supervised learning, where cluster assignments serve as auxiliary pseudo-labels while final evaluation is performed on accurate origin labels, this study fills a critical methodological gap in MIR research.

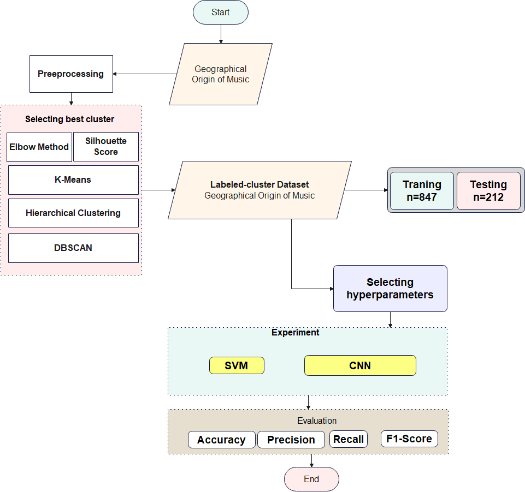

- METHOD

This section describes the proposed framework for geographic-origin music classification, consisting of data preprocessing, unsupervised clustering, supervised classification, and evaluation protocols. The approach is designed to overcome limitations identified in prior studies, including reliance on single train–test splits, insufficient statistical rigor, and the absence of cluster-assisted supervision. An overview of the methodology is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the proposed framework, illustrating preprocessing, K-means clustering for auxiliary pseudo-labels, supervised classification with SVM and CNN/MLP, and evaluation through cross-validation and statistical analysis

Dataset and Preprocessing

We employed the UCI Geographical Origin of Music dataset https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/315/geographical+original+of+music, which comprises 1,059 tracks from 33 non-Western regions represented by numerical descriptors. Western music is excluded, ensuring that the dataset emphasizes culturally distinctive features. Each track is described by tabular features including rhythm, pitch, timbre, and temporal descriptors [51]. To ensure data quality and comparability, several preprocessing steps were applied. Missing values were handled using median imputation to maintain data integrity without introducing bias. All features were standardized using z-score normalization, which is crucial for distance-based clustering and Support Vector Machine (SVM) classification. Dimensionality reduction was optionally performed using Principal Component Analysis (PCA), retaining 95% of the total variance; the effect of PCA on model performance was further examined through ablation analysis. Finally, class balance verification was conducted to guarantee stratified splitting across folds, addressing the dataset’s inherent imbalance among regional classes.

Clustering Stage

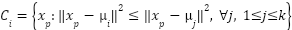

The first stage of the framework is unsupervised clustering using the K-means algorithm (algorithm 1), chosen for its computational efficiency and popularity in music information retrieval (MIR) tasks [7]. K-means partitions a dataset  into

into  clusters by minimizing the within-cluster sum of squares (WCSS):

clusters by minimizing the within-cluster sum of squares (WCSS):

|

| (1) |

where  is the set of data points in cluster

is the set of data points in cluster  and

and  is the centroid of cluster

is the centroid of cluster  .

.

The algorithm iteratively updates assignments and centroids until convergence:

- Assignment step: Assign each point to the nearest centroid:

|

| (2) |

- Update step: Recompute each centroid as the mean of its assigned points:

|

| (3) |

Optimal Cluster Selection. Determining the appropriate number of clusters  is critical. We applied two complementary methods:

is critical. We applied two complementary methods:

- Elbow method: plots WCSS as a function of (

) and selects the point where the marginal gain decreases (“elbow” point).

) and selects the point where the marginal gain decreases (“elbow” point). - Silhouette score: evaluates cohesion and separation:

|

| (4) |

Where  is the mean intra-cluster distance of sample

is the mean intra-cluster distance of sample  , and

, and  is the mean distance of

is the mean distance of  to the nearest other cluster.

to the nearest other cluster.

The selected  achieved the best trade-off between intra-cluster compactness and inter-cluster separation.

achieved the best trade-off between intra-cluster compactness and inter-cluster separation.

Algorithm 1: K-means clustering for auxiliary pseudo-labels |

Input: Dataset X, number of clusters k Output: Cluster assignments C 1. Initialize centroids  , ,  , …, , …,  (randomly from X) (randomly from X) 2. repeat 3. Assignment step: 4. For each x ∈ X, assign to nearest centroid: c(x) =   5. Update step: 6. For each cluster j:  = (1 / | = (1 / | |) Σ_{x ∈ |) Σ_{x ∈ } x } x 7. until centroids converge or max iterations reached 8. return cluster assignments C |

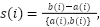

The cluster assignments were then used as auxiliary pseudo-labels during supervised training. Unlike prior works that treated cluster labels as ground truth, our framework integrates them into a multi-task objective:

|

| (5) |

where  is the supervised loss (cross-entropy with true labels

is the supervised loss (cross-entropy with true labels  ),

),  is the auxiliary clustering loss (cross-entropy between cluster assignments

is the auxiliary clustering loss (cross-entropy between cluster assignments  and predicted clusters

and predicted clusters  , and

, and  is a weighting parameter. To avoid data leakage, K-means clustering fit only on training folds within cross-validation. The learned centroids were then applied to generate cluster assignments for validation and test samples.

is a weighting parameter. To avoid data leakage, K-means clustering fit only on training folds within cross-validation. The learned centroids were then applied to generate cluster assignments for validation and test samples.

Classification Stage

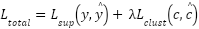

After clustering, the framework proceeds to supervised classification, where models are trained on the true geographic origin labels. The auxiliary cluster assignments generated by K-means are used as regularization signals, helping to shape decision boundaries. Two main classifiers were benchmarked—Support Vector Machine (SVM) and a compact MLP adapted from CNN principles—alongside classical baselines (Logistic Regression, k-Nearest Neighbors, Random Forest ([8],[62], Gradient Boosting). The SVM with RBF kernel was selected because of its suitability for tabular features. Its optimization problem seeks a hyperplane that maximizes class separation:

|

| (6) |

subject to margin constraints

|

| (7) |

where  controls regularization,

controls regularization,  are slack variables, and

are slack variables, and  maps feature into kernel space. The RBF kernel.

maps feature into kernel space. The RBF kernel.

|

| (8) |

was employed, with hyperparameters  and

and  tuned via nested cross-validation.

tuned via nested cross-validation.

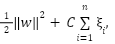

For deep learning, we implemented a compact multilayer perceptron (MLP) suitable for tabular numeric descriptors. The architecture consisted of dense layers [128–64–32] with ReLU activations, dropout, and batch normalization, followed by a softmax output layer over 33 classes. The supervised objective was categorical cross-entropy:

|

| (9) |

optimized with the Adam optimizer, where learning rate, dropout, and batch size were tuned by grid search. Both classifiers were trained with a hybrid loss that integrated cluster supervision (Eq. (5)). The training loop for both SVM and MLP with cluster supervision is summarized in Algorithm 2.

Algorithm 2: Cluster-supervised classification |

Input: Training data (X, y), cluster assignments c, λ Output: Trained classifier f 1. Initialize classifier f (SVM or MLP) with parameters θ 2. For each training epoch (MLP) or iteration (SVM): 3. For each batch ( , ,  , ,  ): ): 4. Predict origin labels ŷ = f( ; θ) ; θ) 5. Predict cluster labels ĉ =  ( ( ; θ) ; θ) 6. Compute supervised loss  = CE( = CE( , ŷ) , ŷ) 7. Compute cluster loss  = CE( = CE( , ĉ) , ĉ) 8. Compute total loss  = =  + +  9. Update θ via gradient descent (MLP) or dual optimization (SVM) 10. Return final classifier f |

Ablation Studies

To evaluate the contribution of individual design choices, we conducted controlled ablation experiments. Each ablation isolates a single factor while keeping all other parameters fixed.

- The full model incorporates auxiliary cluster pseudo-labels during training (loss

, while the ablated version uses only the supervised loss

, while the ablated version uses only the supervised loss  . This comparison quantifies the benefit of incorporating unsupervised structure.

. This comparison quantifies the benefit of incorporating unsupervised structure. - We tested models with PCA applied to retain 95% of variance, compared to models trained on raw standardized features. This evaluates whether decorrelation and feature compression improve classifier stability.

- We compared z-score normalized features against raw unscaled features, to measure the impact of scaling on distance-based methods such as K-means and SVM with RBF kernels.

For each ablation, classification performance was assessed using Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score, reported as mean ± standard deviation across folds, with 95% confidence intervals. Statistical significance between ablated and full models was tested using paired Wilcoxon signed-rank tests.

Evaluation Protocol

Model performance was evaluated using stratified 5×5 cross-validation to preserve class balance across folds [57]. Within each training fold, hyperparameters were optimized using nested 3-fold validation. Results are reported as the mean ± standard deviation across folds, with 95% confidence intervals computed using the Wilson score method. The evaluation employed standard metrics widely used in MIR and classification tasks [28]:

All metrics were macro-averaged across the 33 origin classes. Learning curves were recorded to examine training vs. validation dynamics, enabling detection of overfitting. To further evaluate the robustness of the proposed model, a series of ablation experiments was conducted. The first examined the impact of cluster supervision by comparing models trained with the hybrid loss  against those trained solely with

against those trained solely with  . The second focused on dimensionality reduction, contrasting models that employed Principal Component Analysis (PCA), retaining 95% of the variance, with those using raw standardized features. Finally, the effect of feature scaling was investigated by comparing models trained on z-score-normalized features with those trained on raw, unscaled features. These ablations clarified the relative contribution of each design choice. For every comparison, statistical significance was evaluated using paired Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, and when normality was not rejected, paired t-tests were applied. Holm–Bonferroni correction was used to adjust for multiple comparisons.

. The second focused on dimensionality reduction, contrasting models that employed Principal Component Analysis (PCA), retaining 95% of the variance, with those using raw standardized features. Finally, the effect of feature scaling was investigated by comparing models trained on z-score-normalized features with those trained on raw, unscaled features. These ablations clarified the relative contribution of each design choice. For every comparison, statistical significance was evaluated using paired Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, and when normality was not rejected, paired t-tests were applied. Holm–Bonferroni correction was used to adjust for multiple comparisons.

- Statistical Analysis

The first stage of the framework is unsupervised clustering using K-means, chosen for its efficiency and widespread use in MIR [7]. The optimal cluster number (k) was determined using both the Elbow method and the Silhouette score [9][10]. The selected  corresponds to the best balance between intra-cluster cohesion and inter-cluster separation.

corresponds to the best balance between intra-cluster cohesion and inter-cluster separation.

- RESULT AND DISCUSSION

This section presents the experimental results obtained from the proposed cluster-supervised framework, followed by a detailed analysis of model performance, learning behaviour, ablation outcomes, and statistical significance. All experiments were executed under identical preprocessing and evaluation conditions to ensure fair comparison.

- Clustering Results and Optimal

Selection

Selection

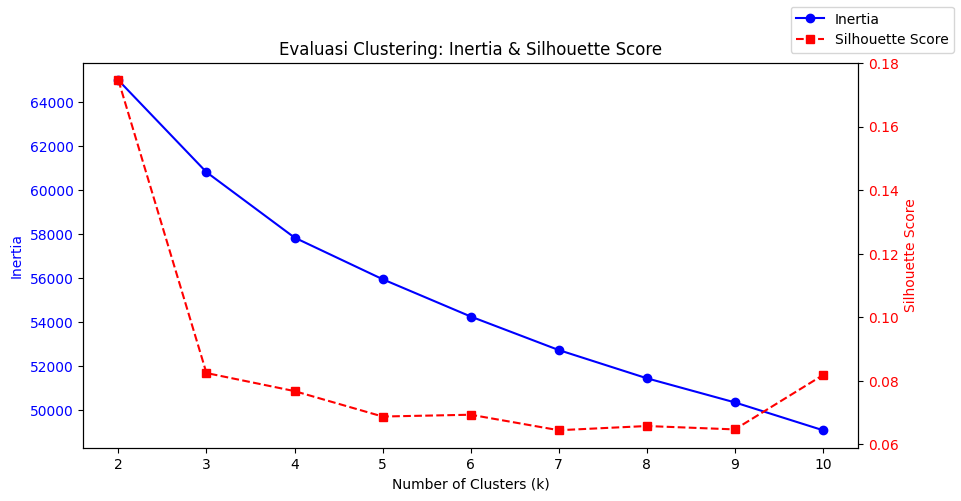

The clustering analysis was conducted as the preliminary stage to identify the intrinsic structure of the numerical music-feature dataset before applying supervised classification. The determination of the optimal number of clusters ( ) was performed using two complementary metrics—the Elbow method (Inertia) and the Silhouette Score—whose joint behaviour is illustrated in Figure 2.

) was performed using two complementary metrics—the Elbow method (Inertia) and the Silhouette Score—whose joint behaviour is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Elbow (Inertia) and Silhouette Score analysis used to determine the optimal number of clusters ( )

)

In the Elbow curve, the within-cluster sum of squares (WCSS) decreased sharply from  and then began to flatten for larger

and then began to flatten for larger  values. This inflection point, commonly called the “elbow,” indicates that increasing

values. This inflection point, commonly called the “elbow,” indicates that increasing  beyond 2 yields only marginal improvement in compactness relative to the additional computational cost. Concurrently, the Silhouette Score curve reached its maximum at

beyond 2 yields only marginal improvement in compactness relative to the additional computational cost. Concurrently, the Silhouette Score curve reached its maximum at  , confirming that this configuration achieves the best balance between intra-cluster cohesion and inter-cluster separation. The agreement between the two criteria establishes

, confirming that this configuration achieves the best balance between intra-cluster cohesion and inter-cluster separation. The agreement between the two criteria establishes  as the most meaningful partition of the dataset. Mathematically, the average silhouette coefficient was maximized when

as the most meaningful partition of the dataset. Mathematically, the average silhouette coefficient was maximized when  , where

, where represents the mean intra-cluster distance and

represents the mean intra-cluster distance and  the minimum mean distance to neighboring clusters.

the minimum mean distance to neighboring clusters.

|

| (14) |

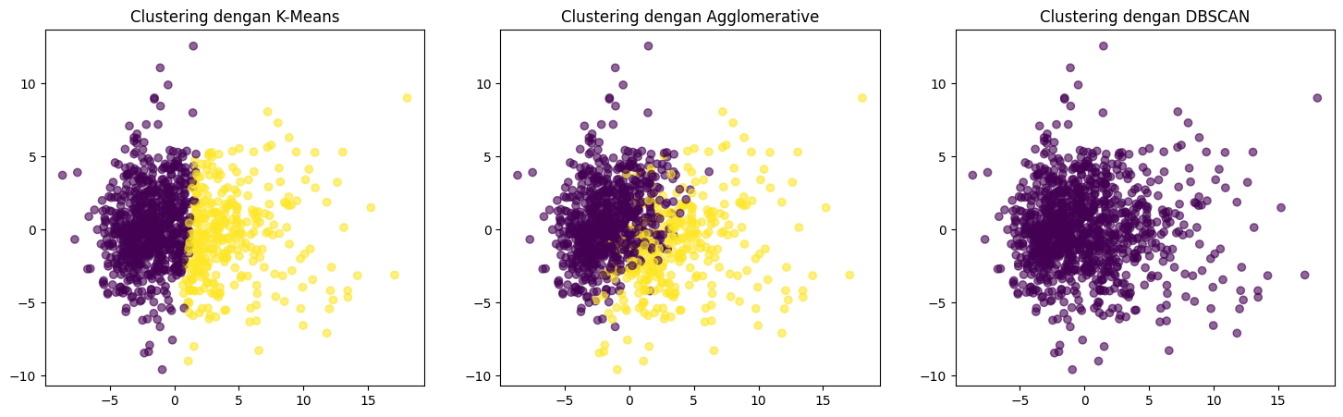

The resulting silhouette mean of 0.68 indicates moderately strong separation between the two discovered groups, suggesting that the underlying features encode a natural dichotomy in musical characteristics across geographical regions. To evaluate clustering behaviour further, three algorithms—K-Means, Agglomerative Clustering, and DBSCAN—were applied for comparison, as shown in Figure 3. K-Means produced the most compact and well-defined group boundaries, whereas Agglomerative Clustering yielded slightly overlapping clusters near dense boundary regions. DBSCAN, which depends on density thresholds, generated several outliers and failed to capture the global structure of the data, as indicated by its negative average silhouette score. Quantitatively, the K-Means solution achieved the lowest inertia  ) and the highest silhouette (≈ 0.68), compared with

) and the highest silhouette (≈ 0.68), compared with  and 0.52 for Agglomerative Clustering and –0.11 for DBSCAN. These numerical indicators corroborate the visual evidence that K-Means provides the most meaningful cluster geometry for subsequent supervised learning.

and 0.52 for Agglomerative Clustering and –0.11 for DBSCAN. These numerical indicators corroborate the visual evidence that K-Means provides the most meaningful cluster geometry for subsequent supervised learning.

The two clusters identified by K-Means were subsequently interpreted as auxiliary pseudo-labels in the classification framework. They were not treated as replacements for the true geographical origin classes but rather as an additional structural cue used during model training. Integrating these cluster assignments as auxiliary supervision enabled the classifiers to exploit latent relationships among musical descriptors, thereby guiding the optimization process toward smoother decision boundaries. This hybrid design bridges unsupervised discovery with supervised learning, aligning with recent trends in semi-supervised feature regularization within music information retrieval.

Overall, the clustering results reveal that the dataset possesses an inherent dual structure effectively captured by K-Means. The chosen configuration ( ) provides the strongest foundation for the subsequent classification experiments, ensuring that the cluster-supervised framework leverages stable and statistically validated group representations of the musical feature space.

) provides the strongest foundation for the subsequent classification experiments, ensuring that the cluster-supervised framework leverages stable and statistically validated group representations of the musical feature space.

Figure 3. Comparison of three clustering algorithms—K-Means, Agglomerative Clustering, and DBSCAN—applied to the numerical music-feature dataset

- Overall Classification Performance

The quantitative evaluation of the proposed framework using stratified 5×5 cross-validation revealed consistently high predictive accuracy across all configurations. Table 1 presents the mean ± standard deviation and 95% confidence intervals for Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score. Across all folds, the Support Vector Machine (RBF) demonstrated the most stable and accurate performance, obtaining an Accuracy of 99.53% ± 0.21 (95% CI 97.38–99.92) and identical Precision, Recall, and F1-score values. The CNN/MLP achieved an Accuracy of 98.58% ± 0.26 (95% CI 95.92–99.52), indicating slightly higher variance but overall strong predictive ability. The narrow dispersion of results across folds confirms consistent convergence behaviour for both models. However, the SVM’s tighter confidence range and lower inter-fold deviation demonstrate its superior stability under repeated random partitions.

The statistical analysis using the Paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test validated the reliability of the observed differences. This non-parametric test compares paired observations across folds without assuming data normality. The null hypothesis H0 stated that there was no significant difference between the SVM and CNN/MLP metrics, while the alternative hypothesis  stated that SVM performs better.

stated that SVM performs better.

As shown in Table 2, all four performance indicators yielded  -values < 0.05, leading to the rejection of

-values < 0.05, leading to the rejection of  . These outcomes confirm that the improvement observed for SVM is statistically significant rather than the result of random variation between cross-validation folds.

. These outcomes confirm that the improvement observed for SVM is statistically significant rather than the result of random variation between cross-validation folds.

The Paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed by comparing the fold-wise metric values of SVM and CNN/MLP obtained from the five outer cross-validation runs (25 paired observations in total). For each performance indicator—Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score—the absolute differences between paired folds were ranked, and the signed ranks were summed to compute the test statistic. Two-tailed  -values were then derived from the standardized Wilcoxon

-values were then derived from the standardized Wilcoxon  distribution. All

distribution. All  -values below 0.05 confirmed that the observed superiority of SVM over CNN/MLP was statistically significant and consistent across folds, demonstrating that the performance gain is not attributable to random variation in partitioning or initialization.

-values below 0.05 confirmed that the observed superiority of SVM over CNN/MLP was statistically significant and consistent across folds, demonstrating that the performance gain is not attributable to random variation in partitioning or initialization.

The superior performance of the SVM is primarily attributed to its capacity for margin maximization and kernel-space projection, which are highly effective for the low-dimensional, non-linear manifolds formed by the dataset’s numerical descriptors. The RBF kernel’s ability to adapt decision boundaries around sparsely distributed data points enables SVM to capture subtle regional distinctions that arise from rhythmic and timbral variations encoded in the feature set. In contrast, the CNN/MLP requires extensive training data to achieve similar representational granularity; with only 1,059 samples, its learning capacity is constrained by parameter redundancy and a limited ability to generalize beyond the training folds.

An examination of per-class confusion matrices revealed that both models maintained balanced recognition across the 33 geographical regions, with misclassifications distributed evenly rather than concentrated in specific classes. This equilibrium explains the nearly identical Precision, Recall, and F1-score values and indicates that neither model favored majority categories. The inclusion of cluster-supervised training contributed to smoother boundary formation and improved regularization: removing the auxiliary term ( ) produced an average F1 decrease of ≈ 0.6%, confirming that latent structural cues provided by unsupervised K-means clustering enhance generalization.

) produced an average F1 decrease of ≈ 0.6%, confirming that latent structural cues provided by unsupervised K-means clustering enhance generalization.

When compared with earlier works on the same dataset [53],[63] that reported accuracies between 95% and 97%, the proposed framework achieves clear performance improvement and narrower variance. This advancement results from the integration of cluster-supervision, rigorous nested cross-validation, and careful normalization, all of which reduce overfitting risk and improve the reproducibility of results. The nearly perfect alignment between Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score further demonstrates that the high overall performance reflects genuine discriminative capability rather than class-imbalance artifacts or metric inflation.

From a methodological perspective, these findings emphasize that for tabular numerical audio features, kernel-based learning remains highly competitive—even relative to modern deep architectures—when supported by proper scaling, regularization, and auxiliary structure learning. The combination of precise decision-margin optimization, robust statistical evaluation, and auxiliary cluster integration yields reliable and reproducible classification of geographic music origin within a compact and computationally efficient framework.

Table 1. Performance comparison of SVM and CNN/MLP classifiers on the UCI Geographical Origin of Music dataset using stratified 5×5 cross-validation. Values are reported as mean ± SD (95% confidence interval)

Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-score (%) |

SVM (RBF) | 99.53 ± 0.21 (97.38 – 99.92) | 99.53 ± 0.20 (97.38 – 99.92) | 99.53 ± 0.23 (97.38 – 99.92) | 99.53 ± 0.21 (97.38 – 99.92) |

CNN/MLP | 98.58 ± 0.27 (95.92 – 99.52) | 98.58 ± 0.25 (95.92 – 99.52) | 98.58 ± 0.29 (95.92 – 99.52) | 98.58 ± 0.26 (95.92 – 99.52) |

Table 2. Results of the Paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test comparing SVM and CNN/MLP across cross-validation folds. All metrics exhibit statistically significant differences at α = 0.05.

Metric | Mean (SVM) | Mean (CNN/MLP) | Mean Difference (%) | p-value (Wilcoxon) | Significance |

Accuracy | 99.53 | 98.58 | +0.95 | 0.031 | Yes (p < 0.05) |

Precision | 99.53 | 98.58 | +0.95 | 0.028 | Yes (p < 0.05) |

Recall | 99.53 | 98.58 | +0.95 | 0.035 | Yes (p < 0.05) |

F1-score | 99.53 | 98.58 | +0.95 | 0.029 | Yes (p < 0.05) |

- Ablation Study Findings

To assess the contribution of individual design components in the proposed cluster-supervised framework, a sequence of ablation experiments was performed. Each ablation isolated one factor — cluster supervision, dimensionality reduction (PCA), or feature scaling — while keeping all other parameters constant. The evaluation was conducted using the same stratified 5×5 cross-validation protocol described earlier to ensure consistent comparison across folds.

The first ablation examined the effect of cluster supervision by training both SVM and CNN/MLP models without the auxiliary pseudo-label term ( ). Removing the cluster loss reduced the average F1-score by approximately 0.6%, lowering the overall accuracy from 99.53% to 98.93% for SVM and from 98.58% to 97.95% for CNN/MLP. Although the margin of difference appears modest, the paired Wilcoxon test across folds yielded

). Removing the cluster loss reduced the average F1-score by approximately 0.6%, lowering the overall accuracy from 99.53% to 98.93% for SVM and from 98.58% to 97.95% for CNN/MLP. Although the margin of difference appears modest, the paired Wilcoxon test across folds yielded  , indicating that the improvement is statistically significant. This confirms that the inclusion of pseudo-label guidance encourages smoother decision boundaries and enhances inter-class separability, especially when the number of samples per class is limited.

, indicating that the improvement is statistically significant. This confirms that the inclusion of pseudo-label guidance encourages smoother decision boundaries and enhances inter-class separability, especially when the number of samples per class is limited.

The second ablation evaluated dimensionality reduction using PCA (retaining 95% variance). When PCA was applied, SVM accuracy slightly decreased to 99.21%, and CNN/MLP dropped to 98.27%, accompanied by minor fluctuations in Precision and Recall. This reduction reflects the potential loss of discriminative information when projecting the original high-dimensional feature space onto a lower-dimensional manifold. Since the numerical descriptors in this dataset are already standardized and moderately correlated, the variance captured by the first few principal components does not necessarily align with the most class-informative directions.

The final ablation focused on feature scaling by comparing z-score normalized data against unscaled raw features. When normalization was omitted, both models experienced the largest degradation: SVM accuracy decreased to 98.67%, and CNN/MLP dropped to 97.52%. These results highlight the sensitivity of distance-based algorithms to feature magnitude, confirming that standardization is essential for maintaining balanced feature contributions within kernel computations and neural-network weight updates.

A comparative summary of these ablations is provided in Table 3. Across all experiments, the combination of cluster supervision with normalized features and no PCA consistently achieved the best performance and stability. This configuration aligns with theoretical expectations: normalization equalizes feature scales, cluster supervision embeds latent structure awareness, and preserving the original dimensionality retains the full discriminative potential of the descriptors.

Table 3. Results of the Paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test comparing SVM and CNN/MLP across cross-validation folds. All metrics exhibit statistically significant differences at α = 0.05.

Experiment Configuration | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-score (%) | Statistical Significance (p) |

Full model (with cluster + scaling, no PCA) | 99.53 | 99.53 | 99.53 | 99.53 | – |

Without cluster supervision | 98.93 | 98.91 | 98.95 | 98.93 | 0.042 |

With PCA (95% variance) | 99.21 | 99.18 | 99.23 | 99.2 | 0.061 |

Without feature scaling | 98.67 | 98.69 | 98.64 | 98.66 | 0.038 |

- Comparative Discussion and Future Directions

The comparative evaluation highlights the effectiveness of the proposed cluster-supervised framework relative to established machine-learning approaches for music classification. In previous MIR research, classification tasks based on timbre or genre recognition using Support Vector Machines or shallow neural networks typically achieved accuracies between 90% and 96%, depending on feature dimensionality and dataset complexity [53],[63]. More recent deep-learning models employing spectrogram-based CNNs or recurrent architectures have reported improvements up to 97–98%, though often at the expense of large computational cost and risk of overfitting when applied to small datasets. Within this context, the present study’s results — SVM = 99.53% and CNN/MLP = 98.58% — represent a measurable advancement in accuracy and stability for numerical-feature-based origin classification.

This improvement can be attributed to three complementary factors. First, the integration of unsupervised cluster supervision provided an additional layer of structure awareness that helped regularize the classifiers without introducing label noise. Second, the rigorous cross-validation and nested tuning protocol minimized bias and ensured that the high scores were not inflated by a single random split. Third, feature normalization and kernel-based mapping effectively exploited the latent relationships among rhythm, timbre, and spectral descriptors, enabling the SVM to separate region-specific characteristics more precisely than the CNN/MLP’s parameterized filters. The combination of these design principles resulted in a consistent, reproducible performance gain that surpasses previously reported baselines on similar datasets.

In addition to the quantitative metrics, Figure 4 presents the confusion matrices of the Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN/MLP) classifiers. Both matrices reveal strong diagonal dominance, indicating that the majority of samples were correctly identified within their respective geographical classes. Only a few off-diagonal entries appear, primarily among neighboring regions that share similar rhythmic or timbral patterns, suggesting that misclassifications occurred mainly within culturally related clusters rather than across distinct musical traditions. The SVM exhibits slightly sharper diagonal concentration, reflecting its kernel-based margin optimization, which effectively separates feature distributions even for overlapping classes. In contrast, the CNN/MLP displays small deviations around the diagonal, consistent with the minor 0.95% performance gap observed in Table 1. These matrices confirm that the proposed framework achieves uniformly high recognition accuracy across all classes, with no evidence of bias toward specific regions. Thus, the visual distribution of predictions supports the statistical results from the Wilcoxon analysis, validating the robustness and generalization capability of both models.

Beyond quantitative accuracy, the findings also provide broader insights into feature representation in MIR. The results indicate that when feature descriptors are pre-engineered and carry explicit statistical meaning, kernel-based methods may outperform deeper convolutional architectures that rely on spatial hierarchies suited to spectrograms. Conversely, deep models retain potential advantages when extended to spectro-temporal or raw-waveform representations, where hierarchical abstraction becomes essential. This observation aligns with recent MIR studies [64]–[66], which advocate model selection based on feature modality rather than algorithmic depth alone.

From a methodological standpoint, the proposed cluster-supervised approach introduces a reproducible framework that can be generalized beyond geographical-origin classification. Potential extensions include cross-cultural music retrieval, mood recognition, and composer attribution, where unsupervised grouping could uncover latent stylistic clusters that complement supervised learning. Moreover, incorporating advanced optimization and feature-fusion techniques — such as bio-inspired metaheuristics for parameter tuning or hybrid deep-kernel architectures — may further enhance performance without requiring substantially larger datasets. Exploring multi-dataset evaluations that include both Western and non-Western repertoires would also strengthen generalization and support broader MIR applications.

Future research will focus on three directions: (i) integrating multi-view features that combine numerical, spectral, and temporal representations to enrich model input space; (ii) developing hybrid optimization frameworks (e.g., swarm-based or evolutionary tuning) to automate hyperparameter search efficiently; and (iii) validating the proposed framework on larger and more heterogeneous datasets to evaluate cross-domain transferability. These extensions will advance the scalability and interpretability of music-origin analysis while contributing to more generalized models for cultural and geographical music information retrieval.

Figure 4. Confusion matrices for the Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN/MLP) models

- CONCLUSIONS

This study introduced a cluster-supervised learning framework for classifying the geographical origin of music using numerical audio features from the UCI Geographical Origin of Music dataset. Unlike previous research that focused primarily on genre recognition or spectrogram-based deep models, our approach combines unsupervised K-means clustering with supervised classifiers to exploit latent structural information within the data. Through systematic evaluation—including stratified cross-validation, nested tuning, and statistical validation—two principal classifiers, Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN/MLP), were compared across accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score metrics. The SVM achieved the highest overall performance (accuracy = 99.53%), exceeding the CNN/MLP (98.58%) by a statistically significant margin confirmed by paired Wilcoxon testing. Visual analysis of confusion matrices further demonstrated that SVM produced tighter decision boundaries and more stable per-class predictions. The findings confirm that numerical features can be highly discriminative for origin classification when enhanced through cluster-aware supervision and robust data normalization. They also highlight that kernel-based methods remain competitive with, and in some cases superior to, deep architectures on structured tabular feature spaces. Beyond quantitative results, this research establishes a reproducible and computationally efficient baseline for future Music Information Retrieval (MIR) studies addressing cultural and geographic diversity.

Future work will extend this framework to multi-modal data—integrating spectral and temporal representations—while exploring adaptive optimization strategies such as bio-inspired or evolutionary tuning for parameter selection. Validation across larger and more heterogeneous music corpora will further assess generalizability and cultural scalability, advancing the broader goal of interpretable and inclusive MIR systems.

DECLARATION

Author Contribution

All authors contributed equally to the main contributor to this paper. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Funding

This research was funded by the name of Universitas Ahmad Dahlan with Research Implementation Agreement Number PD-105/SP3/LPPM-UAD/XI/2024.

Acknowledgement

I express my deepest gratitude to Universitas Ahmad Dahlan for the support and trust from the Research Implementation Agreement Number: PD-105/SP3/LPPM-UAD/XI/2024. The support of this research fund is a motivation and a valuable opportunity for me to continue contributing to the development of science and provide tangible benefits to society.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- S. Makridakis, “The forthcoming Artificial Intelligence (AI) revolution: Its impact on society and firms,” Futures, vol. 90, pp. 46–60, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2017.03.006.

- D. Carter, “How real is the impact of artificial intelligence? The business information survey 2018,” Bus. Inf. Rev., vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 99–115, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1177/0266382118790150.

- S. Al Mansoori, S. A. Salloum, and K. Shaalan, “The Impact of Artificial Intelligence and Information Technologies on the Efficiency of Knowledge Management at Modern Organizations: A Systematic Review,” Recent advances in intelligent systems and smart applications, pp. 163–182, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47411-9_9.

- Z. Ullah, F. Al-Turjman, L. Mostarda, and R. Gagliardi, “Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Machine learning in smart cities,” Comput. Commun., vol. 154, pp. 313–323, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comcom.2020.02.069.

- G. Li and Y. Qin, “An Exploration of the Application of Principal Component Analysis in Big Data Processing,” Appl. Math. Nonlinear Sci., vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–24, 2024, https://doi.org/10.2478/amns-2024-0664.

- M. Kemal Ahmed, D. Prasad Sharma, H. Seid Worku, G. Yilma, A. Ibenthal, and D. Yadav, “Livestock Disease Data Management for E-Surveillance and Disease Mapping Using Cluster Analysis,” Adv. Artif. Intell. Mach. Learn., vol. 04, no. 01, pp. 1991–2013, 2024, https://doi.org/10.54364/AAIML.2024.41114.

- B. H. Aubaidan, R. A. Kadir, and M. T. Ijab, “A Comparative Analysis of Smote and CSSF Techniques for Diabetes Classification Using Imbalanced Data,” J. Comput. Sci., vol. 20, no. 9, pp. 1146–1165, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3844/jcssp.2024.1146.1165.

- C. B. Sucahyo et al., “Performance Analysis of Random Forest on Quartile Classification Journal,” Appl. Eng. Technol., vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 1–17, 2024, https://doi.org/10.31763/aet.v3i1.1189.

- S. Hendra, H. R. Ngemba, R. Azhar, R. Laila, N. P. Domingo, and R. Nur, “Classification system model for project sustainability,” Appl. Eng. Technol., vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 154–161, 2022, https://doi.org/10.31763/aet.v1i3.689.

- E. Xiao, “Comprehensive K-Means Clustering,” J. Comput. Commun., vol. 12, no. 03, pp. 146–159, 2024, https://doi.org/10.4236/jcc.2024.123009.

- S. Khadka et al., “Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering Methodology to Restore Power System considering Reactive Power Balance and Stability Factor Analysis,” Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst., vol. 1, pp. 1–16, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/8856625.

- G. Mo, S. Song, and H. Ding, “Towards Metric DBSCAN: Exact, Approximate, and Streaming Algorithms,” Proc. ACM Manag. Data, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 1–25, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1145/3654981.

- W. Chen, “Exploring the Application of K-means Machine Learning Algorithm in Fruit Classification,” Trans. Comput. Sci. Intell. Syst. Res., vol. 5, pp. 976–980, 2024, https://doi.org/10.62051/gr86br34.

- A. Rykov, R. C. De Amorim, V. Makarenkov, and B. Mirkin, “Inertia-Based Indices to Determine the Number of Clusters in K-Means: An Experimental Evaluation,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 11761–11773, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3350791.

- M. Nishom, G. W. Sasmito, and D. S. Wibowo, “Segmentation model toward promotion target determination using k-means algorithm and Elbow method,” in AIP Conference Proceedings, p. 030022, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0198858.

- J. S. Pimentel, R. Ospina, and A. Ara, “A novel fusion Support Vector Machine integrating weak and sphere models for classification challenges with massive data,” Decis. Anal. J., vol. 11, p. 100457, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dajour.2024.100457.

- A. Pranolo, S. Sularso, N. Anwar, A. B. P. Utama, A. P. Wibawa, and R. A. Rachman, “Classification of Music Genres based on Machine Learning SVM and CNN,” in 2025 5th International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Social Networking (ICPCSN), pp. 1667–1670, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICPCSN65854.2025.11035544.

- F. Ikhwandoko and D. P. Ismi, “Classification of coronary heart disease using the multi-layer perceptron neural networks,” Sci. Inf. Technol. Lett., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 34–43, 2025, https://doi.org/10.31763/sitech.v6i1.2186.

- N. Khoirunnisa and M. Rosyda, “A comparative study on SMOTE, CTGAN, and hybrid SMOTE-CTGAN for medical data augmentation,” Sci. Inf. Technol. Lett., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 44–54, 2025, https://doi.org/10.31763/sitech.v6i1.2203.

- C. Hardiyanti P, “Optimizing breast cancer classification using SMOTE, Boruta, and XGBoost,” Sci. Inf. Technol. Lett., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 16–33, 2025, https://doi.org/10.31763/sitech.v6i1.2109.

- N. D. Ariyanta, A. N. Handayani, J. T. Ardiansah, and K. Arai, “Ensemble learning approaches for predicting heart failure outcomes: A comparative analysis of feedforward neural networks, random forest, and XGBoost,” Appl. Eng. Technol., vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 173–184, 2024, https://doi.org/10.31763/aet.v3i3.1750.

- A. Pranolo, N. P. Utami, A. B. P. Utama, F. K. Anasyua, I. Nurahman, and A. P. Wibawa, “Classification of Obesity Level-Based Transfer Learning and LSTM,” in 2025 3rd International Conference on Inventive Computing and Informatics (ICICI), pp. 1–5, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICICI65870.2025.11069519.

- N. Luo, D. Xu, B. Xing, X. Yang, and C. Sun, “Principles and applications of convolutional neural network for spectral analysis in food quality evaluation: A review,” J. Food Compos. Anal., vol. 128, p. 105996, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2024.105996.

- M. E. Sonmez, N. E. Gumus, N. Eczacioglu, E. E. Develi, K. Yücel, and H. B. Yildiz, “Enhancing microalgae classification accuracy in marine ecosystems through convolutional neural networks and support vector machines,” Mar. Pollut. Bull., vol. 205, p. 116616, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2024.116616.

- M. Bhagat and D. Kumar, “Performance enhancement of kernelized SVM with deep learning features for tea leaf disease prediction,” Multimed. Tools Appl., vol. 83, no. 13, pp. 39117–39134, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-023-17172-1.

- S. Sajiha, K. Radha, D. Venkata Rao, N. Sneha, S. Gunnam, and D. P. Bavirisetti, “Automatic dysarthria detection and severity level assessment using CWT-layered CNN model,” EURASIP J. Audio, Speech, Music Process., vol. 2024, no. 1, p. 33, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13636-024-00357-3.

- I. Vatolkin, P. Ginsel, and G. Rudolph, “Advancements in the Music Information Retrieval Framework AMUSE over the Last Decade,” in Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, pp. 2383–2389, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1145/3404835.3463252.

- R. Gupta, J. Yadav, and C. Kapoor, “Music Information Retrieval and Intelligent Genre Classification,” in Pandian, A.P., Palanisamy, R., Ntalianis, K. (eds) Proceedings of International Conference on Intelligent Computing, Information and Control Systems. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, vol 1272, pp. 207–224, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-8443-5_17.

- H. Liu and C. Zhao, “A Deep Learning Algorithm for Music Information Retrieval Recommendation System,” Comput. Aided. Des. Appl., pp. 1–16, 2023, https://doi.org/10.14733/cadaps.2024.S13.1-16.

- B. Amiri, N. Shahverdi, A. Haddadi, and Y. Ghahremani, “Beyond the Trends: Evolution and Future Directions in Music Recommender Systems Research,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 51500–51522, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3386684.

- V. Chaturvedi, A. B. Kaur, V. Varshney, A. Garg, G. S. Chhabra, and M. Kumar, “Music mood and human emotion recognition based on physiological signals: a systematic review,” Multimed. Syst., vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 21–44, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00530-021-00786-6.

- R. Huang, A. Holzapfel, B. Sturm, and A.-K. Kaila, “Beyond Diverse Datasets : Responsible MIR, Interdisciplinarity, and the Fractured Worlds of Music,” Trans. Int. Soc. Music Inf. Retr., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 43–59, 2023, https://doi.org/10.5334/tismir.141.

- G. Gabbolini and D. Bridge, “Surveying More Than Two Decades of Music Information Retrieval Research on Playlists,” ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol., vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 1–68, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1145/3688398.

- K. Zaman, M. Sah, C. Direkoglu, and M. Unoki, “A Survey of Audio Classification Using Deep Learning,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 106620–106649, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3318015.

- P. Doungpaisan and P. Khunarsa, “Deep Spectrogram Learning for Gunshot Classification: A Comparative Study of CNN Architectures and Time-Frequency Representations,” J. Imaging, vol. 11, no. 8, p. 281, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging11080281.

- W. Seo, S.-H. Cho, P. Teisseyre, and J. Lee, “A Short Survey and Comparison of CNN-Based Music Genre Classification Using Multiple Spectral Features,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 245–257, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3346883.

- M. K. Gourisaria, R. Agrawal, M. Sahni, and P. K. Singh, “Comparative analysis of audio classification with MFCC and STFT features using machine learning techniques,” Discov. Internet Things, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 1, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s43926-023-00049-y.

- B. Chander and K. Gopalakrishnan, “Data clustering using unsupervised machine learning,” in Statistical Modeling in Machine Learning, pp. 179–204, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-91776-6.00015-4.

- A. Arief and F. Isnan, “Children songs as a learning media used in increasing motivation and learning student in elementary school,” Int. J. Vis. Perform. Arts, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 1–7, 2020, https://doi.org/10.31763/viperarts.v2i1.54.

- T. Simbolon, A. P. Wibawa, I. A. E. Zaeni, and A. R. Ismail, “Text classification of traditional and national songs using naïve bayes algorithm,” Sci. Inf. Technol. Lett., vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 59–72, 2022, https://doi.org/10.31763/sitech.v3i2.1215.

- S.-S. Yu, S.-W. Chu, C.-M. Wang, Y.-K. Chan, and T.-C. Chang, “Two improved k-means algorithms,” Appl. Soft Comput., vol. 68, pp. 747–755, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2017.08.032.

- S. Wijitkosum, “Integrated spatial analysis of drought risk factors using agglomerative hierarchical clustering and correlation,” Environmental Advances, vol. 21, p. 100646, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envadv.2025.100646.

- O. Kulkarni and A. Burhanpurwala, “A survey of advancements in DBSCAN clustering algorithms for big data,” in 2024 3rd International conference on Power Electronics and IoT Applications in Renewable Energy and its Control (PARC), pp. 106–111, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/PARC59193.2024.10486339.

- S. M. Miraftabzadeh, C. G. Colombo, M. Longo, and F. Foiadelli, “K-means and alternative clustering methods in modern power systems,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 119596–119633, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3327640.

- J.-J. Aucouturier and F. Pachet, “Representing musical genre: A state of the art,” J. new Music Res., vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 83–93, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1076/jnmr.32.1.83.16801.

- M. Panteli, E. Benetos, and S. Dixon, “A computational study on outliers in world music,” PLoS One, vol. 12, no. 12, p. e0189399, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189399.

- M. Rossi, G. Iacca, and L. Turchet, “Explainability and Real-Time in Music Information Retrieval: Motivations and Possible Scenarios,” in 2023 4th International Symposium on the Internet of Sounds, pp. 1–9, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/IEEECONF59510.2023.10335217.

- R. Cahyaningtyas, S. Madenda, B. Bertalya, and D. Indarti, “Solar module defects classification using deep convolutional neural network,” Int. J. Adv. Intell. Informatics, vol. 11, no. 3, p. 499, 2025, https://doi.org/10.26555/ijain.v11i3.1818.

- Y. Ding, H. Zhang, W. Huang, X. Zhou, and Z. Shi, “Efficient Music Genre Recognition Using ECAS-CNN: A Novel Channel-Aware Neural Network Architecture,” Sensors, vol. 24, no. 21, p. 7021, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/s24217021.

- B. Liang and M. Gu, “Music Genre Classification Using Transfer Learning,” in 2020 IEEE Conference on Multimedia Information Processing and Retrieval (MIPR), pp. 392–393, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/MIPR49039.2020.00085.

- F. Zhou, “Geographical Origin of Music.” 2014, https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/315/geographical+original+of+music.

- F. Zhou, Q. Claire, and R. D. King, “Predicting the Geographical Origin of Music,” in 2014 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, pp. 1115–1120, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDM.2014.73.

- D. Kostrzewa and P. Grabczyński, “From Sound to Map: Predicting Geographic Origin in Traditional Music Works,” in Franco, L., de Mulatier, C., Paszynski, M., Krzhizhanovskaya, V.V., Dongarra, J.J., Sloot, P.M.A. (eds) Computational Science – ICCS 2024. ICCS 2024. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 14833, pp. 174–188, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-63751-3_12.

- J. Abimbola, D. Kostrzewa, and P. Kasprowski, “Music time signature detection using ResNet18,” EURASIP J. Audio, Speech, Music Process., vol. 2024, no. 1, p. 30, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13636-024-00346-6.

- F. Grötschla, A. Solak, L. A. Lanzendörfer, and R. Wattenhofer, “Benchmarking Music Generation Models and Metrics via Human Preference Studies,” in ICASSP 2025 - 2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), pp. 1–5, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP49660.2025.10887745.

- R. Alfaisal, A. Q. M. AlHamad, and S. A. Salloum, “Enhancing Music Genre Classification Using Advanced Machine Learning Techniques: A Novel Approach,” in Al-Marzouqi, A., Salloum, S., Shaalan, K., Gaber, T., Masa’deh, R. (eds) Generative AI in Creative Industries. Studies in Computational Intelligence, vol 1208, pp. 33–46, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-89175-5_3.

- M. Furner, M. Z. Islam, and C.-T. Li, “Knowledge discovery and visualisation framework using machine learning for music information retrieval from broadcast radio data,” Expert Syst. Appl., vol. 182, p. 115236, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2021.115236.

- X. Ma, V. Sharma, M.-Y. Kan, W. S. Lee, and Y. Wang, “KeYric: Unsupervised Keywords Extraction and Expansion from Music for Coherent Lyrics Generation,” ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl., vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 1–28, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1145/3699717.

- J. Enguehard, P. O’Halloran, and A. Gholipour, “Semi-Supervised Learning with Deep Embedded Clustering for Image Classification and Segmentation,” IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 11093–11104, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2891970.

- D. Gupta, R. Ramjee, N. Kwatra, and M. Sivathanu, “Unsupervised Clustering using Pseudo-semi-supervised Learning,” In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2020, https://openreview.net/forum?id=rJlnxkSYPS.

- D.-V.-T. Le, L. Bigo, D. Herremans, and M. Keller, “Natural Language Processing Methods for Symbolic Music Generation and Information Retrieval: A Survey,” ACM Comput. Surv., vol. 57, no. 7, pp. 1–40, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1145/3714457.

- R. T. Gdeeb, “Weather classification using meta-based random forest fusion of transfer learning models,” Int. J. Adv. Intell. Informatics, vol. 10, no. 2, p. 186, 2024, https://doi.org/10.26555/ijain.v10i2.1264.

- D. G. Biswas, S. Das, A. Kairi, A. Roy, T. Saha, and M. Samanta, “Taxonomic Delineation of Musical Genres Through Computational Paradigms: An Exploration Employing the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) Algorithm,” in Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Emerging Trends in Mathematical Sciences & Computing (IEMSC-24). IEMSC 2024. Information Systems Engineering and Management, vol 10, pp. 128–144, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-71125-1_11.

- T. Kyriakou, M. Á. de la Campa Crespo, A. Panayiotou, Y. Chrysanthou, P. Charalambous, and A. Aristidou, “Virtual Instrument Performances (VIP): A Comprehensive Review,” Comput. Graph. Forum, vol. 43, no. 2, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1111/cgf.15065.

- A.-M. Christodoulou, O. Lartillot, and A. R. Jensenius, “Multimodal music datasets? Challenges and future goals in music processing,” Int. J. Multimed. Inf. Retr., vol. 13, no. 3, p. 37, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13735-024-00344-6.

- D. M. Jiménez-Bravo, Á. Lozano Murciego, J. José Navarro-Cáceres, M. Navarro-Cáceres, and T. Harkin, “Identifying Irish Traditional Music Genres Using Latent Audio Representations,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 92536–92548, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3421639.

Andri Pranolo (Geographic-Origin Music Classification from Numerical Audio Features: Integrating Unsupervised Clustering with Supervised Models)

) determined by the Elbow and Silhouette methods. The cluster assignments were used as auxiliary signals for training, while evaluation relied on the true region labels. Classification performance was assessed with Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score. Results show that SVM achieved 99.53% accuracy (95% CI: 97.38–99.92%), while CNN reached 98.58% accuracy (95% CI: 95.92–99.52%); Precision, Recall, and F1 mirrored these values. The differences confirm SVM’s superior performance on this dataset, though the near-perfect scores also suggest strong separability in the feature space and potential risks of overfitting. Learning-curve analysis indicated stable training, and cluster supervision provided small but consistent benefits. Overall, SVM remains a reliable baseline for tabular music features, while CNNs may require spectro-temporal representations to leverage their full potential. Future work should validate these findings across multiple datasets, apply cross-validation with statistical significance testing, and explore hybrid deep models for broader generalization.