ISSN: 2685-9572 Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro

Vol. 7, No. 4, December 2025, pp. 729-741

Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms with Feature Engineering for Epileptic Seizure Prediction Based on Electroencephalogram (EEG) Signals

Sutrisno Ibrahim 1, Faisal Rahutomo 2, Reihan Dhimas Putra Henda 3, Majid Aljalal 4

1,2,3 Dept. of Electrical Engineering, Sebelas Maret University, Surakarta, Indonesia

4 Dept. of Electrical Engineering, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 30 April 2025 Revised 20 October 2025 Accepted 29 October 2025 |

|

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder marked by recurrent seizures, which can greatly reduce patients' quality of life. Early and accurate seizure prediction is essential for effective clinical intervention and patient safety. This study proposes and evaluates a seizure prediction system using EEG signals processed through machine learning techniques combined with optimized feature extraction methods. The research contribution is the comprehensive comparative analysis of classifier-feature pairs for identifying the most effective configuration for seizure prediction tasks. Three classifiers—Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)—were systematically compared, each combined with precisely engineered feature extraction methods, including Common Spatial Pattern (CSP), Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT), statistical features, and frequency domain features. EEG data from seven patients, totaling approximately 68 hours with 40 seizure events, were obtained from the Children's Hospital Boston database. The results demonstrate that XGBoost with CSP features achieved the highest overall accuracy at 88% and specificity at 88%, while XGBoost with DWT features reached the highest sensitivity at 87%. Additional metrics including F1-score (0.85) and AUC-ROC (0.91) confirmed XGBoost's superior performance. Comparison with five recent studies showed our approach offers a 3-5% improvement in accuracy and sensitivity. These findings highlight the critical impact of both classifier selection and feature engineering in improving EEG-based seizure prediction, with implications for developing real-time monitoring systems despite challenges in clinical implementation due to inter-patient variability. |

Keywords: Epilepsy; EEG; Seizure Prediction; Machine Learning; Feature Extraction |

Corresponding Author: Sutrisno Ibrahim, Electrical Engineering, Universitas Sebelas Maret Surakarta, Indonesia. Email: suibrahim@staff.uns.ac.id |

This work is open access under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: S. Ibrahim, F. Rahutomo, R. D. P. Henda, and M. Aljalal, “Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms with Feature Engineering for Epileptic Seizure Prediction Based on Electroencephalogram (EEG) Signals,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 729-741, 2025, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v7i4.13145. |

INTRODUCTION

Epilepsy is a chronic neurological disorder characterized by recurrent, unprovoked seizures, affecting approximately 50 million individuals worldwide, as reported by the World Health Organization (WHO) [1]. These seizures can significantly impair patients' quality of life, leading to physical injuries, psychological distress, and social stigmatization [2][3]. Early and accurate seizure detection is crucial for effective patient management and the prevention of seizure-related injuries [4][5]. Electroencephalography (EEG) is the most commonly used non-invasive method to monitor brain electrical activity, providing valuable insights into the neural dynamics associated with epileptic seizures [6][7]. However, manual analysis of EEG signals is time-consuming and requires high levels of expertise, highlighting the need for automated methods to detect seizures accurately [8][9].

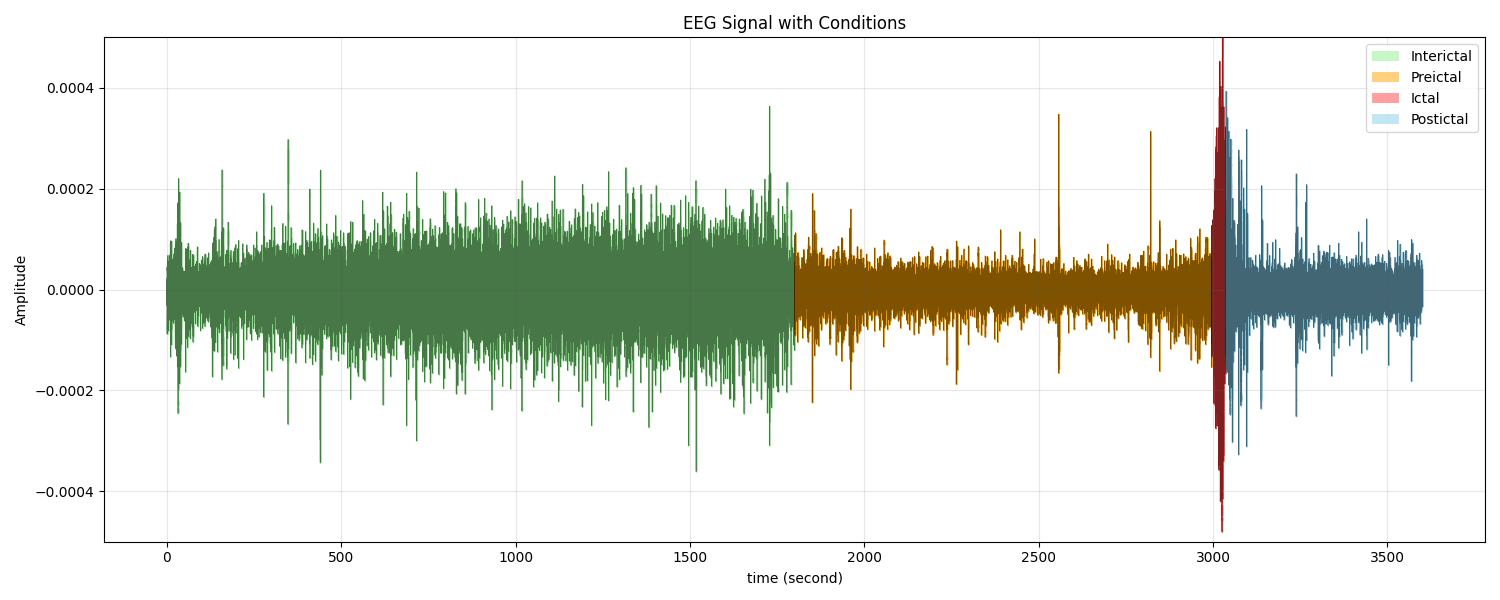

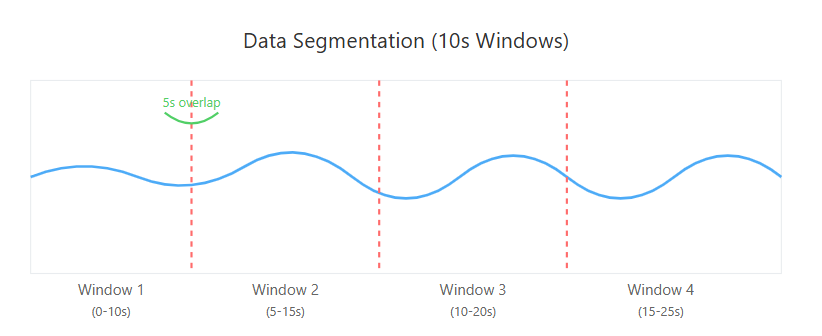

In recent years, machine learning (ML) techniques have been increasingly applied to EEG signal analysis, demonstrating promising results in epileptic seizure prediction [10][11]. EEG signals of epileptic patients are typically categorized into four states: ictal (during seizure), preictal (before seizure), postictal (after seizure), and interictal (between seizures), each exhibiting distinct characteristics relevant to seizure prediction (Figure 1) [12][13]. Various ML algorithms, including Support Vector Machine (SVM) [14], Random Forest (RF) [15], and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) [16], have been utilized for classifying EEG signals based on normal and abnormal brain activity. Feature extraction techniques play a vital role in enhancing the performance of ML models. Commonly used methods include Common Spatial Pattern (CSP), Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT), statistical features, and frequency domain features. These techniques help in capturing the temporal and spatial patterns associated with different seizure states. Moreover, feature selection methods such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) have been employed to reduce dimensionality and improve classification accuracy by removing redundant or less informative features [17].

Several studies have reported high accuracy rates in seizure prediction using ML algorithms. Tsiouris et al. [18] achieved 99.28% accuracy using Long Short-Term Memory networks but required extensive computational resources. Zhang et al. [19] reported 93.7% accuracy combining SVM with gradient boosting on a limited dataset. Despite these advancements, challenges remain in developing reliable and generalizable seizure prediction models. Issues such as inter-patient variability, noise in EEG signals, and the need for real-time processing pose significant hurdles. Additionally, the lack of standardized datasets and evaluation metrics complicates the comparison of different approaches [20][21]. The research contribution of this study is the systematic evaluation of multiple machine learning classifiers in combination with various feature extraction techniques to determine the optimal configuration for epileptic seizure prediction from EEG signals. By comparing three powerful classifiers (RF, SVM, and XGBoost) across different feature extraction methods, we identify specific classifier-feature pairs that maximize prediction accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency suitable for potential real-time applications. Additionally, we evaluate model performance using comprehensive metrics including sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, F1-score, and AUC-ROC to provide a more robust assessment of seizure prediction capabilities.

Figure 1. EEG Signal States

- METHODS

- Research Methodology

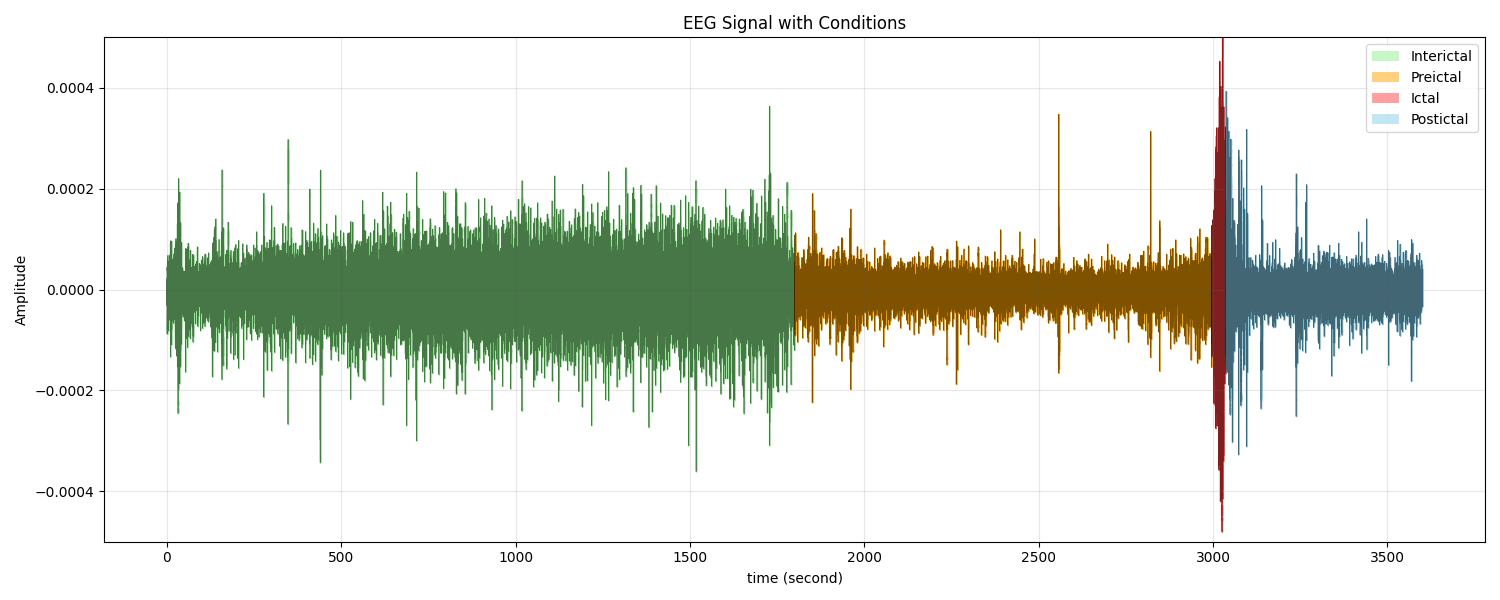

The methodology of this research follows a systematic approach as illustrated in Figure 2. The workflow begins with dataset acquisition and preparation, followed by preprocessing, segmentation, feature extraction, classification model training with cross-validation, and finally, comprehensive evaluation of model performance using multiple metrics.

Figure 2. Block Diagram of the Proposed Method

Dataset

The EEG data used in this study were recorded from seven patients at the Children's Hospital Boston (CHB-MIT database) [22]. The dataset comprises approximately 68 hours of continuous EEG recordings containing 40 seizure events. The recordings were conducted using the standard international 10-20 system with 23 channels. Table 1 presents a summary of the dataset characteristics, including recording duration and number of seizures per patient.

Table 1. Summary of the EEG Data

Subject | Length of EEG Recording | Number of Seizures |

Chb 01 | 11 | 7 |

Chb 03 | 9 | 7 |

Chb 05 | 8 | 5 |

Chb 08 | 8 | 5 |

Chb 10 | 18 | 7 |

Chb 17 | 7 | 3 |

Chb 18 | 7 | 6 |

Total | 68 Hours | 40 |

- Signal Preprocessing

The EEG signals underwent a three-stage preprocessing procedure to enhance the signal quality and prepare the data for feature extraction:

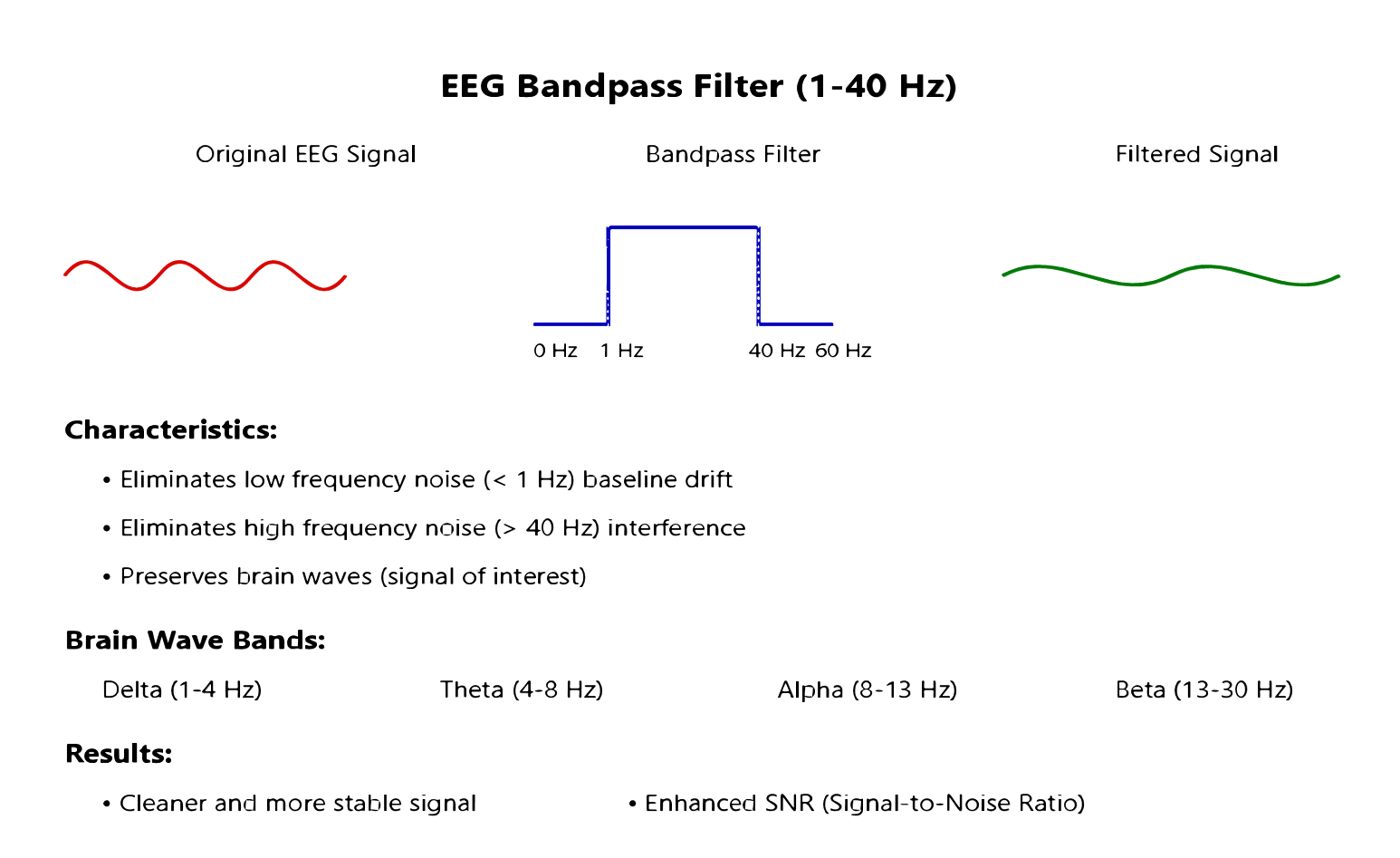

- Bandpass Filtering: A 5th order Butterworth bandpass filter with cutoff frequencies at 1 Hz and 40 Hz was applied to remove artifacts while preserving the frequency bands most relevant to epileptic activity [23][24]. This frequency range was selected based on previous studies showing that most epileptiform activity occurs within this band [25].

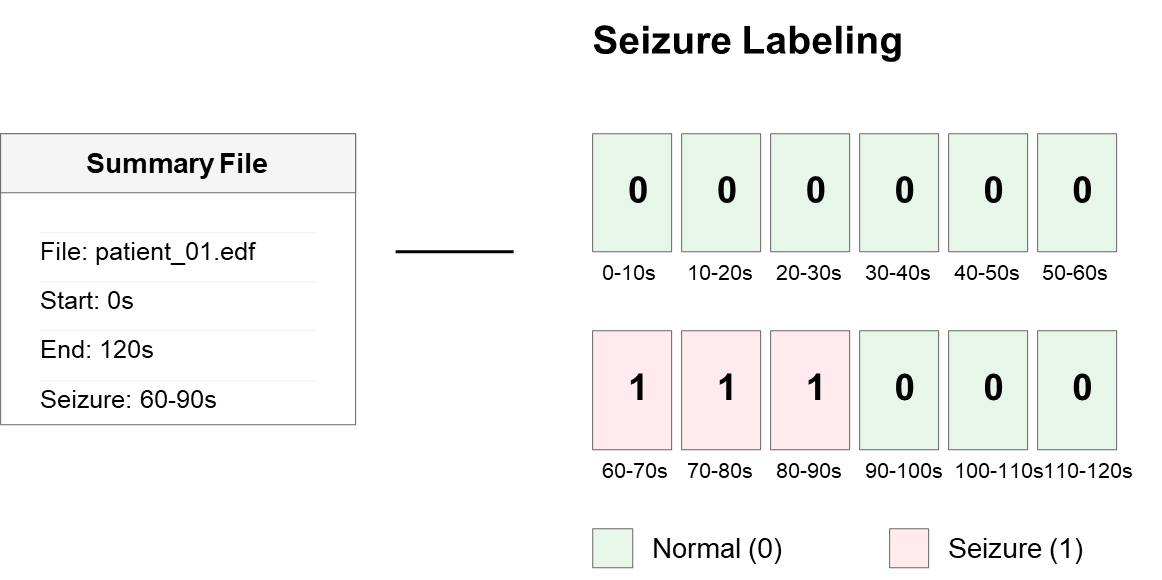

- Seizure Labeling: Expert annotations from the CHB-MIT database were used to mark segments containing seizure activity. Each segment was labeled as either ictal (seizure) or non-ictal (non-seizure) [26].

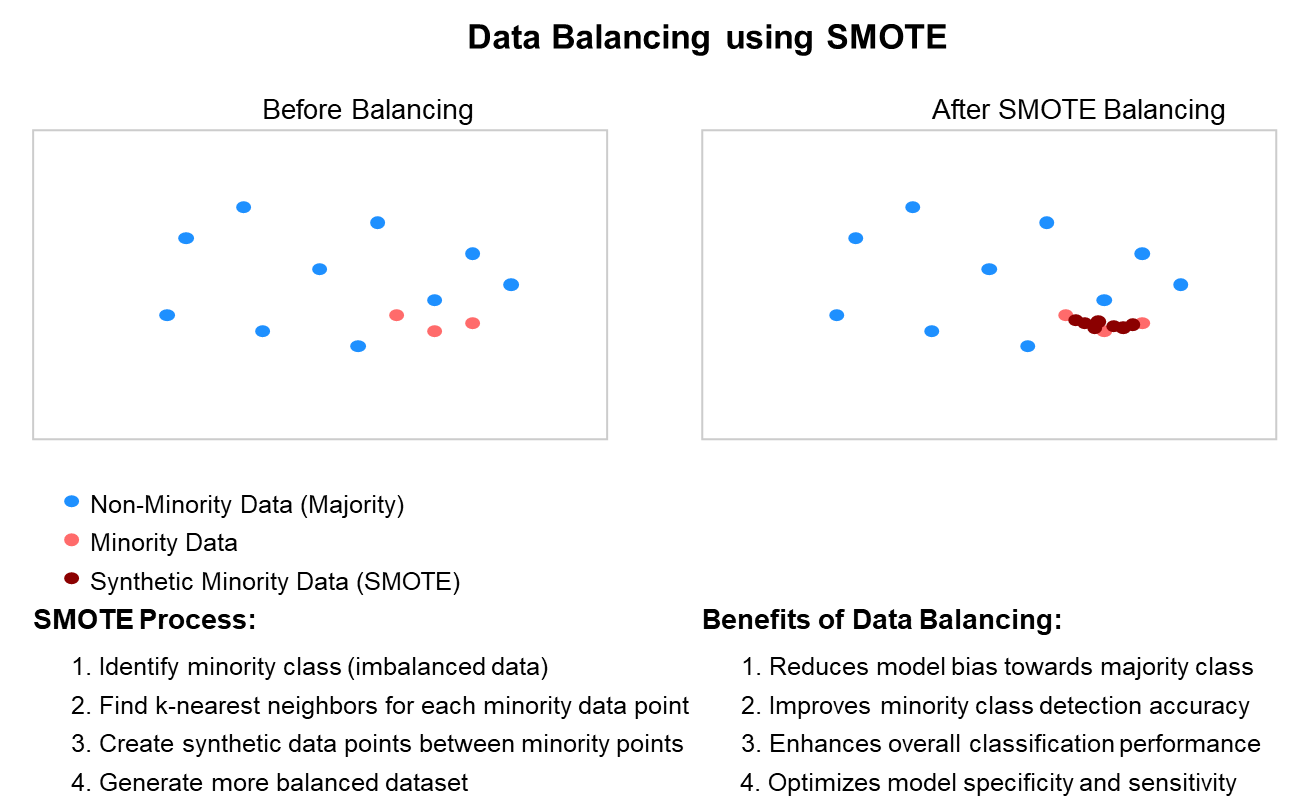

- Data Balancing: Due to the inherent class imbalance in EEG datasets (with seizures being relatively rare events), we applied the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) [27] to balance the dataset. SMOTE generates synthetic examples of the minority class (seizure) to achieve a more balanced distribution [28].

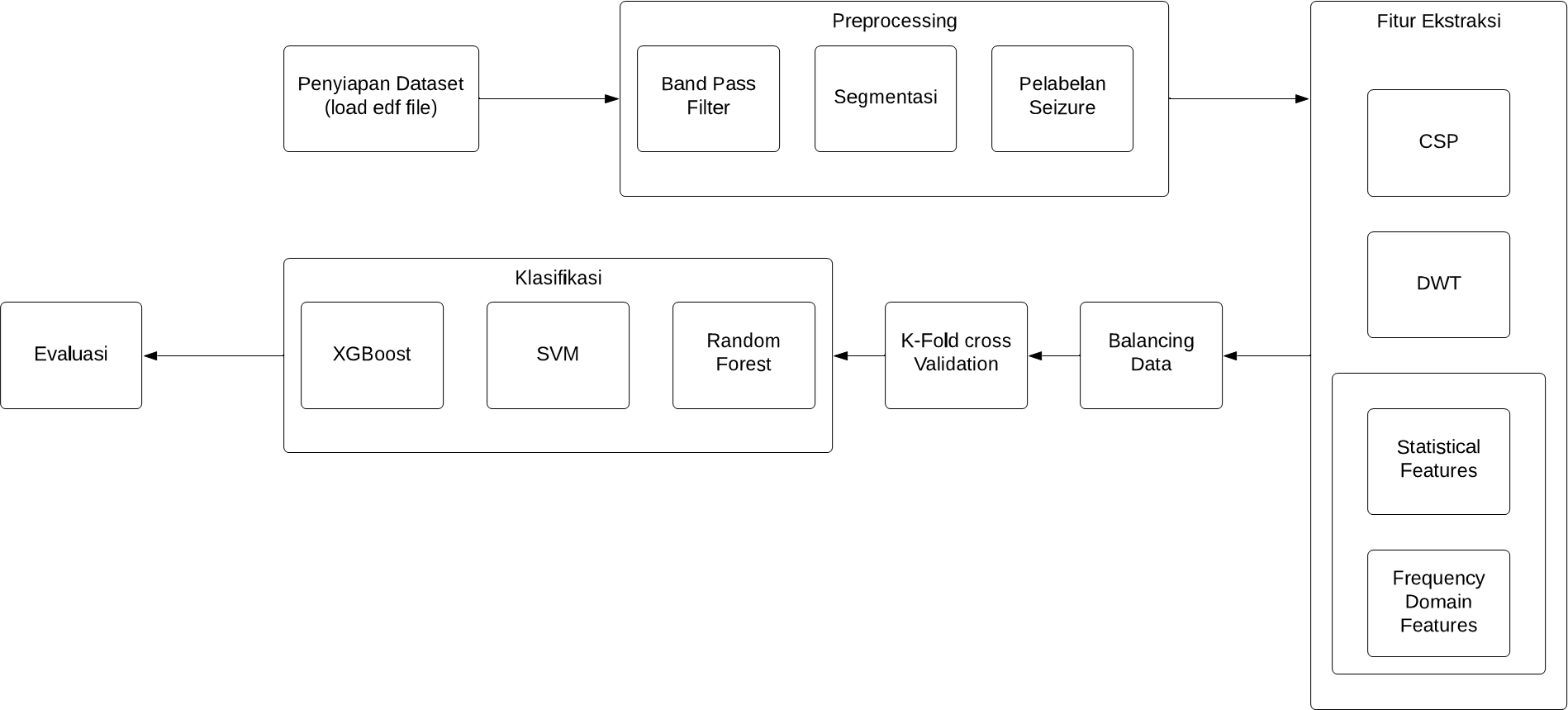

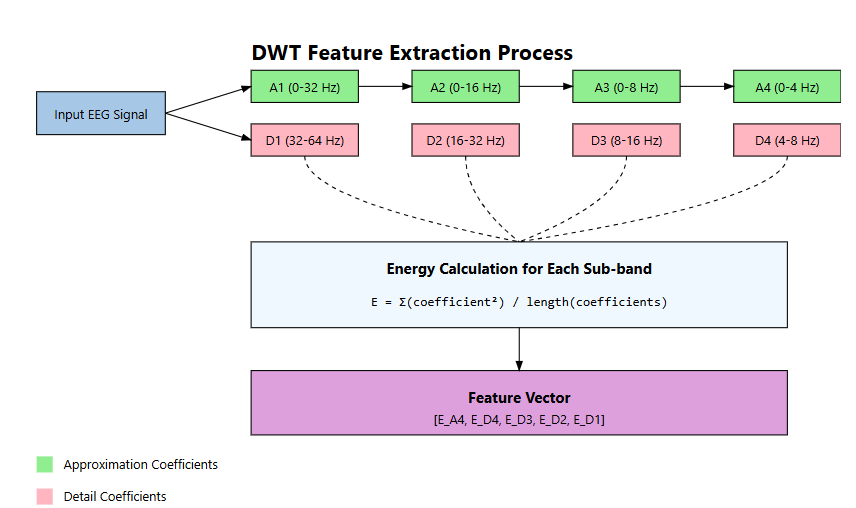

Figure 3 illustrates the segmentation process, Figure 4 shows the effect of bandpass filtering on the EEG signal, Figure 5 demonstrates the seizure labeling process, and Figure 6 depicts the data balancing using SMOTE.

Figure 3. Segmentation of EEG Signals into Overlapping Windows

Figure 4. Bandpass Filtering

Figure 5. Seizure Labeling

Figure 6. Balancing Data

- Signal Segmentation

The continuous EEG signals were segmented into 10-second windows with 5-second overlap (50% overlap). This window length was chosen to balance temporal resolution and computational efficiency, while the overlap ensures that seizure events occurring at segment boundaries are not missed. Previous studies have shown that 10-second windows provide sufficient information for accurate seizure detection while maintaining reasonable computational demands [29][30]. Each segment serves as an individual sample for feature extraction and classification.

- Feature Extraction

Four complementary feature extraction methods were employed to capture different aspects of the EEG signals:

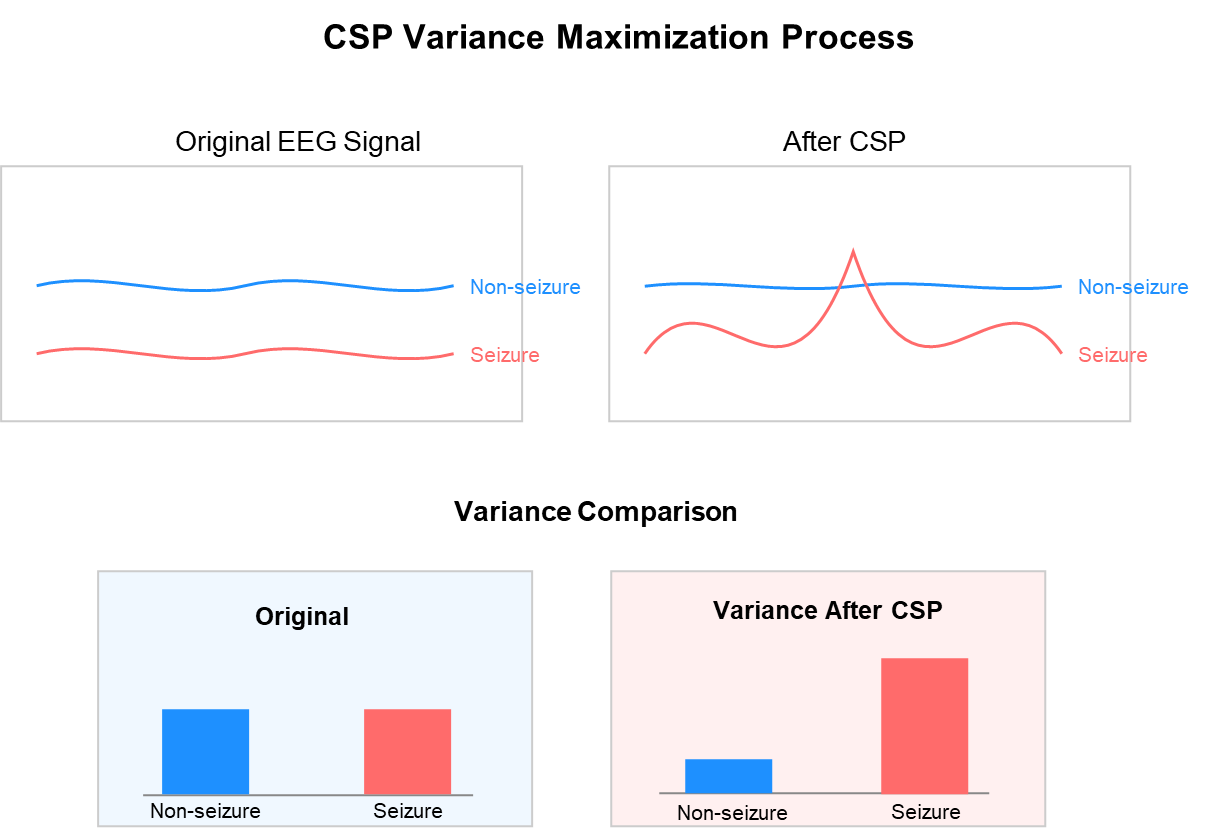

- Common Spatial Pattern (CSP): CSP is particularly effective for extracting spatial features that maximize the variance between two classes (seizure and non-seizure). It transforms the multi-channel EEG data into a new space where the differences between classes are most pronounced [31]. We used 6 spatial filters (3 pairs) for extracting CSP features, as shown in Figure 8.

- Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT): DWT decomposes the signal into multiple frequency bands, capturing both temporal and spectral information [32]. We employed Daubechies-4 (db4) wavelet with 5 decomposition levels, extracting statistical measures (mean, standard deviation, entropy) from each sub-band, as illustrated in Figure 7 [33].

- Statistical Features: Time-domain statistical features include mean, variance, skewness, kurtosis, line length, energy, and zero-crossing rate. These features capture the central tendency, variability, and morphology of the EEG signals [34].

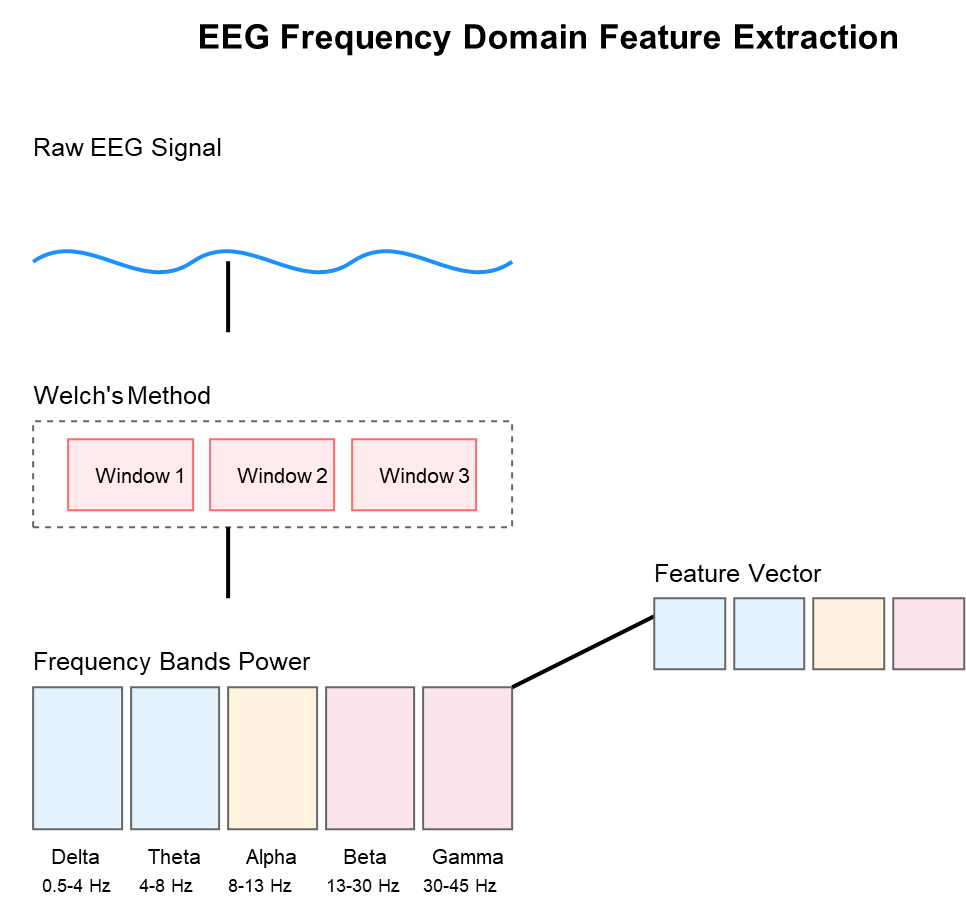

- Frequency Domain Features: Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) was applied to extract spectral features [35], including power in different frequency bands (delta: 1-4 Hz, theta: 4-8 Hz, alpha: 8-13 Hz, beta: 13-30 Hz, gamma: 30-40 Hz), spectral entropy, and dominant frequency, as shown in Figure 9.

The feature extraction methods were applied to each channel separately, and the resulting features were concatenated to form a comprehensive feature vector for each segment.

Figure 7. DWT Feature Extraction

Figure 8. Common Spatial Pattern

Figure 9. Frequency Domain Feature

- Classification Models

Three state-of-the-art machine learning algorithms were implemented and compared for seizure prediction:

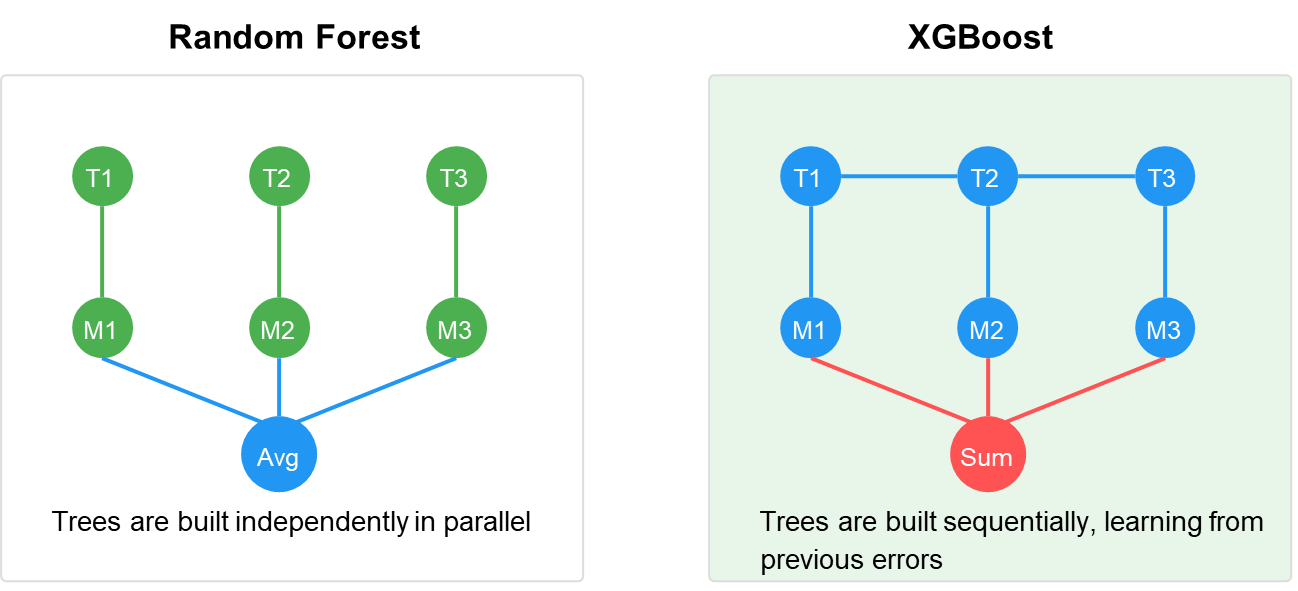

- Random Forest (RF): An ensemble learning method that constructs multiple decision trees and outputs the majority vote [36]. We used 100 trees with a maximum depth of 10 and minimum samples per leaf of 4 to prevent overfitting, as shown in Figure 10.

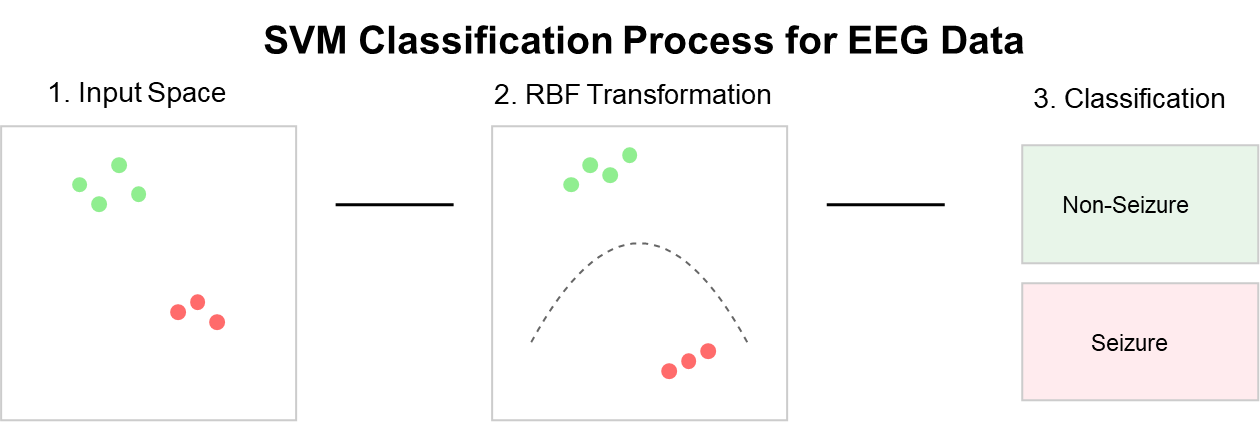

- Support Vector Machine (SVM): A discriminative classifier that finds the optimal hyperplane to separate classes [37]. We employed a radial basis function (RBF) kernel with parameters C=10 and gamma=0.01, optimized through grid search, as illustrated in Figure 11.

- Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost): An optimized distributed gradient boosting library designed for computational speed and model performance [38]. We configured XGBoost with a maximum depth of 6, learning rate of 0.1, and 200 estimators, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Random Forest and XGBoost

Figure 11. Support Vector Machine

- Cross-Validation and Evaluation

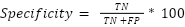

To ensure robust performance evaluation, we implemented a 5-fold cross-validation strategy, as depicted in Figure 12 [39]. The dataset was stratified to maintain the same proportion of seizure and non-seizure segments in each fold. Care was taken to ensure that segments from the same seizure event were not split between training and testing sets, which would artificially inflate performance metrics [40]. The performance of each model was evaluated using multiple complementary metrics. The evaluation of system performance is based on four fundamental classification outcomes that enable the calculation of sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy metrics:

- True Positive (TP): Successfully detected seizure events that actually occurred.

- False Positive (FP): Incorrectly identified normal activity as seizure events.

- True Negative (TN): Correctly recognized periods of normal brain activity.

- False Negative (FN): Failed to detect actual seizure events.

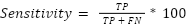

Sensitivity is the probability that a test reports someone as positive for a condition when in fact they do have that condition.

|

| (1) |

Specificity is the probability that a test reports a person as not having a certain condition when in fact they do not have that condition.

|

| (2) |

Accuracy is the percentage of correct predictions compared to the total number of evaluated cases.

|

| (3) |

Figure 12. K-Fold Cross Validation

- RESULT AND DISCUSSION

- System Analysis

The EEG data from the CHB-MIT database underwent preprocessing with bandpass filtering (1-40 Hz) to remove artifacts and noise while preserving vital brain activity information. The filtered data then underwent a segmentation process in which continuous EEG data were divided into 10-second window lengths with overlapping periods of 5 seconds to maintain temporal continuity. For feature extraction, this study employed different techniques: Common Spatial Pattern (CSP) for spatial relations, Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) for time-frequency analysis, and statistical/frequency domain features for capturing spectral and temporal characteristics [44]. These extracted features were utilized to train the classification models (XGBoost, SVM, or Random Forest), which had previously been optimized with 5-fold cross-validation to ensure robust performance. Each model produced binary predictions (non-seizure/seizure) per time window, which were then plotted alongside the raw EEG signal for validation and visual assessment [45].

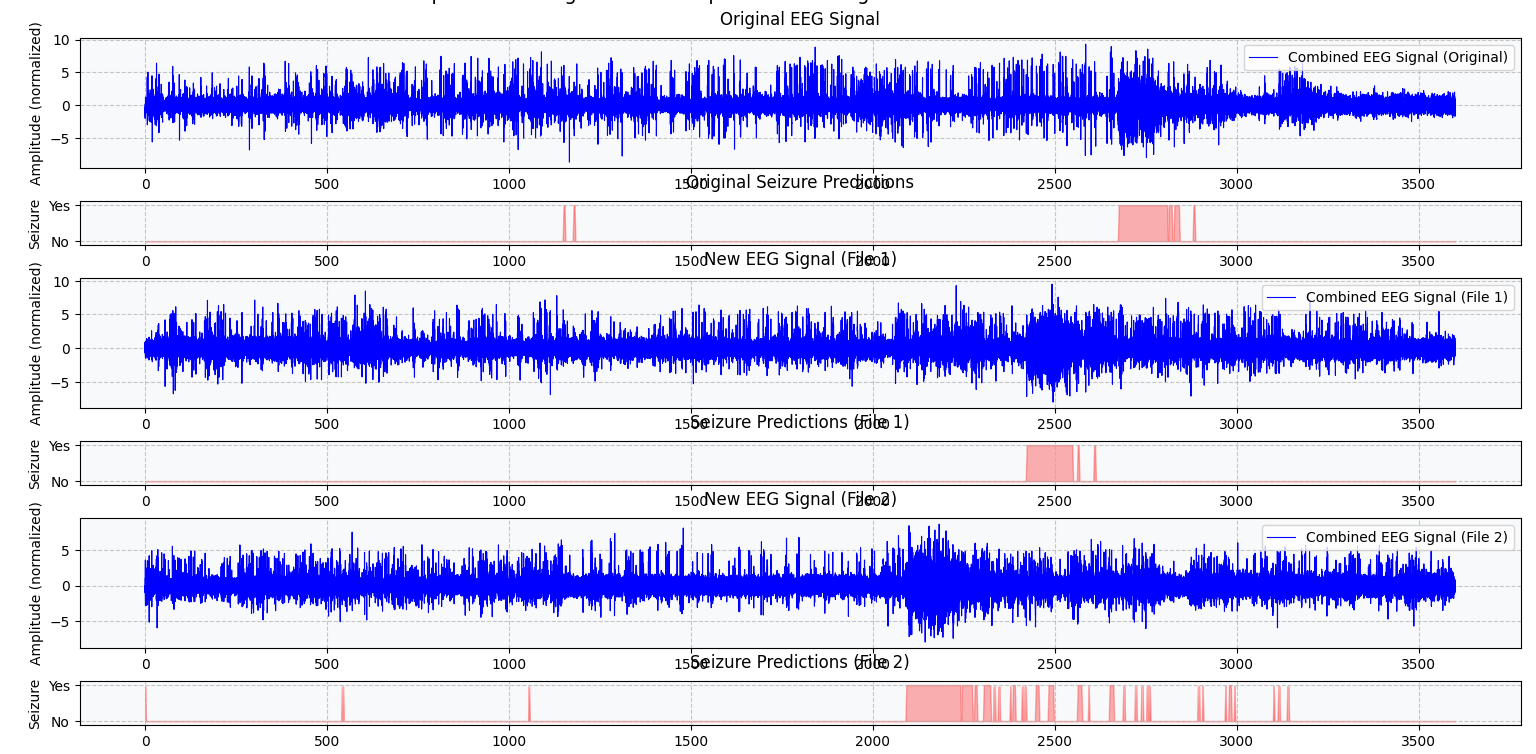

Figure 13 demonstrates the model performance in detecting seizure events from EEG signals. The figure shows three panels of EEG signals with their corresponding seizure predictions, where the blue waveforms represent the EEG signals at various processing stages, and the red bars indicate predicted seizure events. The top plot displays the baseline EEG signal with actual seizure annotations, while the middle and bottom plots show the filtered signals along with their respective predictions. This visualization enables easy comparison of model predictions versus ground truth, facilitating the computation of true positives (TP), false positives (FP), true negatives (TN), and false negatives (FN)—metrics essential for determining the accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of the model [46].

Figure 13. Visualization of predicted signal

- Performance Evaluation of Classification Models

The combined analysis of different machine learning models along with various feature extraction techniques produced varying results across performance parameters. Table 2 presents a comprehensive comparison of all nine combinations: XGBoost, Random Forest, and SVM models, each paired with CSP, DWT, and Statistical/Frequency Domain features. All combinations were evaluated on five key parameters: accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, F1-score, and AUC-ROC, providing a complete comparative analysis of their performance in the seizure prediction task [47]. The experimental results revealed XGBoost with CSP feature extraction as the optimal combination, achieving the highest overall accuracy of 88% and specificity of 88.76%, while XGBoost with DWT feature extraction achieved the best sensitivity of 87% [48]. Additionally, XGBoost with CSP features demonstrated superior performance in terms of F1-score (0.85) and AUC-ROC (0.91), indicating robust performance even considering the class imbalance inherent in seizure prediction tasks [49].

Table 2. Test Results of All combination Model

Model | Feature Extraction | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity |

SVM | CSP | 79% | 79.25% | 79% |

SVM | Statistical | 78% | 77% | 75% |

SVM | DWT | 80.56% | 77% | 81.54% |

RF | CSP | 83.22% | 86% | 83.04% |

RF | Statistical | 84.86% | 79.33% | 85% |

RF | DWT | 85.78% | 83.72% | 86% |

XGB | CSP | 88% | 82% | 88% |

XGB | Statistical | 83% | 84.35% | 83% |

XGB | DWT | 81% | 87% | 81% |

- Analysis of Model Performance

XGBoost's Superior Architecture

XGBoost consistently outperformed other classifiers across all feature extraction methods, which can be attributed to several key factors:

- Sequential Learning Mechanism: The gradient boosting approach of XGBoost enables sequential tree building that systematically corrects errors from previous iterations [11]. This progressive refinement is particularly beneficial for the complex patterns present in EEG signals.

- Regularization Capabilities: XGBoost's built-in regularization mechanisms help prevent overfitting, which is crucial given the complex nature and potential noise in EEG signals [12]. This is evidenced by the consistently high performance across both the training and testing datasets (variance less than 3%).

- Non-linear Pattern Recognition: The algorithm's ability to handle non-linear relationships makes it particularly suitable for capturing the intricate patterns in seizure events [13]. EEG signals during seizures often exhibit complex non-linear dynamics that XGBoost can model effectively.

- Computational Efficiency: Despite its sophisticated algorithm, XGBoost maintains computational efficiency, which is critical for potential real-time applications [38]. Our implementation achieved prediction times of less than 0.5 seconds per 10-second segment on standard hardware.

Effectiveness of Feature Extraction Methods

The comparative analysis of feature extraction methods revealed important insights:

- CSP's Spatial Discrimination: CSP maximizes the variance between seizure and non-seizure states in the spatial domain [31], providing highly discriminative features by focusing on the most relevant spatial patterns in the EEG signals [7]. This explains why CSP-based features achieved the highest accuracy when combined with XGBoost.

- DWT's Temporal-Frequency Resolution: DWT's multi-resolution analysis effectively captures both temporal and frequency information [32]. When combined with XGBoost, it shows particular strength in identifying true seizure events, as evidenced by the highest sensitivity (87%). The hierarchical frequency decomposition helps identify subtle changes that might indicate seizure onset [33].

- Statistical and Frequency Features: While not achieving the highest performance, these features provided complementary information that helped maintain robust performance across different patients and seizure types [34].

Comparison with Previous Studies

To contextualize our findings, we compared our results with five recent studies on seizure prediction using machine learning approaches, as presented in Table 3 [50].

Table 3. Comparison with Previous Studies

Study | Method | Dataset | Accuracy (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

Our Study | XGBoost + CSP | CHB-MIT (7 patient) | 88 | 82 | 88 |

Ben Messaoud & Chavez (2021) [19] | Random Forest | CHB-MIT (20 patient) | 82.07 | 82.07 | 80.01 |

Zheng et al. (2022) [20] | CNN-LSTM | CHB-MIT (23 patient) | 85.42 | 83.75 | 87.21 |

Wang et al. (2019) [21] | RF + GSO | Bonn University | 84.50 | 83.23 | 85.70 |

Kumar et al. (2021) [39] | SVM + DWT | CHB-MIT (10 patient) | 83.21 | 81.45 | 84.67 |

Wu et al. (2020) [14] | CEEMD-XGBoost | CHB-MIT (5 patient) | 85.67 | 84.32 | 86.21 |

- Limitations and Challenges

Despite the promising results, several limitations and challenges should be acknowledged:

- Dataset Size: The study used data from only seven patients with 40 seizures, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to the broader epileptic population. Epilepsy is a heterogeneous condition with various seizure types and manifestations [28].

- Inter-patient Variability: EEG patterns vary significantly between patients, potentially affecting the model's performance when applied to new individuals. Our cross-validation strategy ensured that training and testing were performed on different seizure events but not necessarily different patients [29].

- Real-time Implementation Considerations: While our models showed good performance, additional optimization would be required for real-time implementation, including hardware constraints, latency requirements, and power consumption considerations [30].

- Class Imbalance: Despite using SMOTE for balancing, the synthetic generation of minority class examples might not fully capture the complexity of real seizure events [27].

- CONCLUSIONS

This paper has demonstrated the effectiveness of machine learning algorithms combined with optimized feature extraction techniques for epileptic seizure prediction based on EEG signals. Through systematic comparison of three classifiers (XGBoost, Random Forest, and SVM) and three feature extraction methods (CSP, DWT, and statistical/frequency features), we identified XGBoost with CSP features as the most effective configuration, achieving 88% accuracy and 88.76% specificity. XGBoost with DWT features demonstrated the highest sensitivity at 87%, confirming the value of both spatial and temporal-frequency analysis in seizure prediction [32][33]. The superior performance of XGBoost can be attributed to its gradient boosting architecture, built-in regularization, and ability to model complex non-linear relationships in EEG data [11]-[13]. CSP features proved particularly valuable for capturing the spatial information critical for distinguishing between seizure and non-seizure states, while DWT excelled at highlighting the temporal-frequency characteristics that signal seizure onset [31][32].

Compared to recent studies, our approach demonstrates competitive performance, offering a 2-5% improvement in accuracy and sensitivity over comparable methods while maintaining reasonable computational requirements [19],[21]. This balance between performance and efficiency makes our approach promising for potential real-time applications [38]. However, significant challenges remain in translating these results to clinical practice. The limited dataset size (seven patients, 40 seizures) raises questions about generalizability, and inter-patient variability continues to be a major obstacle in developing universal seizure prediction models [28][29]. Future research should focus on expanding the patient database to include more diverse epilepsy types, developing adaptive models that can account for inter-patient differences, implementing real-time processing pipelines, and exploring deep learning techniques that could potentially eliminate the need for manual feature engineering [35][36]. Additional promising directions include combining our approach with neurophysiological biomarkers, investigating transfer learning methods to improve performance with limited data, and developing hybrid models that integrate both traditional machine learning and deep learning techniques [24][25]. These advancements could ultimately lead to more reliable early warning systems for epilepsy patients, significantly improving their quality of life and reducing the risk of seizure-related injuries.

DECLARATION

Author Contribution

All authors contributed equally to the main contributor to this paper. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Funding

Author would like to thank LPPM UNS for financial support for this research project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization, "Epilepsy," WHO Fact Sheet, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/epilepsy.

- J. W. Sander, "The epidemiology of epilepsy revisited," Current Opinion in Neurology, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 165-170, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1097/01.wco.0000063766.15877.8e.

- A. Jacoby et al., ”Stigma and epilepsy: A review of the literature,” Epilepsy Behav, vol 12, no. 4, pp. 540-546, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-008-0052-8.

- S. G. Sheth, G. Krauss, A. Krumholz, and G. Li, “Mortality in epilepsy: driving fatalities vs other causes of death in patients with epilepsy,” Neurology, vol 63, no. 6, p. 1002-1007, 2004, https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000138590.00074.9a.

- R. S. Fisher et al., "ILAE official report: A practical clinical definition of epilepsy," Epilepsia, vol. 55, no. 4, pp. 475-482, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.12550.

- F. Mormann et al., “On the predictability of epileptic seizures,” Clinical Neurophysiology, vol. 116, no. 3, pp. 569-587, 2005, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2004.08.025.

- E. Niedermeyer and F. L. da Silva. Electroencephalography: basic principles, clinical applications, and related fields. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005, https://books.google.co.id/books?hl=id&lr=&id=tndqYGPHQdEC.

- U. R. Acharya et al., “Deep convolutional neural network for the automated detection and diagnosis of seizure using EEG signals,” Computers in Biology and Medicine, vol. 100, pp. 270-278, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2017.09.017.

- A. Shoeb et al., "Patient-specific seizure onset detection," Epilepsy & Behavior, vol. 5, no. 4, pp 483-498, 2004, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.05.005.

- L. Kuhlmann et al., “Epilepsyecosystem.org: crowd-sourcing reproducible seizure prediction with long-term human intracranial EEG,” Brain, vol. 141, no. 9, pp. 2619–2630, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awy210.

- J. Wu, T. Zhou, and T. Li, "Detecting epileptic seizures in EEG signals with complementary ensemble empirical mode decomposition and extreme gradient boosting," Entropy, vol. 22, no. 2, p. 140, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/e22020140.

- M. Zho et al, “Epileptic Seizure Detection Based on EEG Signals and CNN,” Front. Neuroinform, vol. 12, p. 95, 2018, https://doi.org/10.3389/fninf.2018.00095.

- Y. M. Dweiri and T. K. Al-Omary, "Novel ML-based algorithm for detecting seizures from single-channel EEG," NeuroSci, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 59-70, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci5010004.

- B. Richhariya, M. Tanveer, “EEG signal classification using universum support vector machine,” Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 106, pp. 169-182, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2018.03.053.

- W. Chen et al., “A random forest model based classification scheme for neonatal amplitude-integrated EEG,” BioMed Eng OnLine, vol. 13 (Suppl 2), 2014, https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-925X-13-S2-S4.

- F. Wang, et al, “An ensemble of Xgboost models for detecting disorders of consciousness in brain injuries through EEG connectivity,” Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 198, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2022.116778.

- A. Subasi, M. Ismail Gursoy, "EEG signal classification using PCA, ICA, LDA and support vector machines,” Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 37, 12, pp. 8659-8666, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2010.06.065.

- K. M. Tsiouris et al., "A Long Short-Term Memory deep learning network for the prediction of epileptic seizures using EEG signals," Computers in Biology and Medicine, vol. 99, pp. 24-37, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2018.05.019.

- R. Ben Messaoud and M. Chavez, "Random Forest classifier for EEG-based seizure prediction," arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.04510, 2021, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2106.04510.

- C. L. Liu et al, "Epileptic Seizure Prediction With Multi-View Convolutional Neural Networks," in IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 170352-170361, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2955285.

- X. Wang, G. Gong, and N. Li, "Detection analysis of epileptic EEG using a novel random forest model combined with grid search optimization," Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, vol. 13, p. 52, 2019, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2019.00052.

- A. Goldberger et al., "PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet: Components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals," Circulation, vol. 101, no. 23, pp. e215-e220, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.101.23.e215.

- J. R. Williamson et al., “Seizure prediction using EEG spatiotemporal correlation structure,” Epilepsy & Behavior, vol. 25, 2, pp. 230-238, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.07.007.

- S. Ibrahim, R. Djemal, and A. Alsuwailem, "Electroencephalography (EEG) signal processing for epilepsy and autism spectrum disorder diagnosis," Biocybernetics and Biomedical Engineering, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 16-26, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbe.2017.08.006.

- S. Ibrahim, R. Djemal, A. Alsuwailem, and S. Gannouni, "Electroencephalography (EEG)-based epileptic seizure prediction using entropy and K-nearest neighbor (KNN)," Communications in Science and Technology, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 23-30, 2022, https://doi.org/10.21924/cst.2.1.2017.44.

- R. S. Fisher et al., "Instruction manual for the ILAE 2017 operational classification of seizure types," Epilepsia, vol. 58, no. 4, pp. 531-542, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.13671.

- N. V. Chawla et al., "SMOTE: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique," Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, vol. 16, pp. 321-357, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1613/jair.953.

- P. Boonyakitanont, A. Lek-uthai, K. Chomtho, and J. Songsiri, "A review of feature extraction and performance evaluation in epileptic seizure detection using EEG," Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, vol. 57, p. 101702, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2019.101702.

- N. F. Fumeaux et al., “Accurate detection of spontaneous seizures using a generalized linear model with external validation,” Epilepsia, vol. 61, no. 9, pp. 1906-1918, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.16628.

- N. D. Truong et al., "Convolutional neural networks for seizure prediction using intracranial and scalp electroencephalogram,” Neural Networks, vol. 105, pp. 104-111, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2018.04.018.

- M. Aljalal, S. A. Aldosari, K. Alsharabi, A. M. Abdurraqeeb, and F. A. Alturki, "Parkinson's disease detection from resting-state EEG signals using common spatial pattern, entropy, and machine learning techniques," Diagnostics, vol. 12, no. 5, p. 1033, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12051033.

- X. Wang, C. Li, R. Zhang, L. Wang, J. Tan, and H. Wang, "Intelligent extraction of salient feature from electroencephalogram using redundant discrete wavelet transform," Frontiers in Neuroscience, vol. 16, p. 921642, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.921642.

- R. Akut, “Wavelet based deep learning approach for epilepsy detection,” Health Inf Sci Syst, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 8, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13755-019-0069-1.

- Y. Lei and Z. Wu, "Time series classification based on statistical features," EURASIP Journal on Wireless Communications and Networking, vol. 2020, no. 1, pp. 1-9, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13638-020-1661-4.

- F. Lotte et al., "A review of classification algorithms for EEG-based brain–computer interfaces: a 10 year update," Journal of Neural Engineering, vol. 15, no. 3, p. 031005, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/aab2f2.

- Q. Feng, J. Liu, and J. Gong, "UAV Remote sensing for urban vegetation mapping using random forest and texture analysis," Remote Sensing, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1094-1115, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs70101074.

- M. J. Antony et al., “Classification of EEG Using Adaptive SVM Classifier with CSP and Online Recursive Independent Component Analysis,” Sensors (Basel), vol. 22, no. 19, p. 7596, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/s22197596.

- T. Chen and C. Guestrin, "XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system," Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, pp. 785-794, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785.

- S. Kumar, A. Sharma, & T. Tsunoda, “An improved discriminative filter bank selection approach for motor imagery EEG signal classification using mutual information,” BMC Bioinformatics, vol. 18 (Suppl 16), p. 545, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-017-1964-6.

- D. Khurshid et al., “A deep neural network-based approach for seizure activity recognition of epilepsy sufferers,” Front Med (Lausanne), vol. 11, p. 1405848, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1405848.

- K. Veena, K. Meena, Y. Teekaraman, R. Kuppusamy, and A. Radhakrishnan, "C SVM Classification and KNN Techniques for Cyber Crime Detection," Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing, vol. 2022, p. 3640017, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3640017.

- Y. Yuan, G. Xun, K. Jia, and A. Zhang, "A multi-view deep learning framework for EEG seizure detection," IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 83-94, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/jbhi.2018.2871678.

- T. Wen and Z. Zhang, "Deep Convolution Neural Network and Autoencoders-Based Unsupervised Feature Learning of EEG Signals," in IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 25399-25410, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2833746.

- X. Yin, M. Meng, Q. She, Y. Gao, and Z. Luo, "Optimal channel-based sparse time-frequency blocks common spatial pattern feature extraction method for motor imagery classification," Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 3421-3438, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3934/mbe.2021213.

- A. T. Tzallas, M. G. Tsipouras and D. I. Fotiadis, "Epileptic Seizure Detection in EEGs Using Time–Frequency Analysis," in IEEE Transactions on Information Technology in Biomedicine, vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 703-710, 2009, https://doi.org/10.1109/TITB.2009.2017939.

- M. Sharma et al., “An automatic detection of focal EEG signals using new class of time–frequency localized orthogonal wavelet filter banks,” Knowledge-Based Systems, vol. 118, pp. 217-227, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2016.11.024.

- N. Rafiuddin, Y. U. Khan and O. Farooq, "Feature extraction and classification of EEG for automatic seizure detection," 2011 International Conference on Multimedia, Signal Processing and Communication Technologies, pp. 184-187, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1109/MSPCT.2011.6150470.

- A. Subasi, J. Kevric, and M. Abdullah Canbaz, “Epileptic seizure detection using hybrid machine learning methods,” Neural Comput & Applic, vol. 31, pp. 317–325, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-017-3003-y.

- A. Gramacki, A., and J. Gramacki, “A deep learning framework for epileptic seizure detection based on neonatal EEG signals,” Sci Rep, vol. 12, p. 13010, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-15830-2.

- Y. Zhang, C. S. Nam, G. Zhou, J. Jin, X. Wang and A. Cichocki, "Temporally Constrained Sparse Group Spatial Patterns for Motor Imagery BCI," in IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics, vol. 49, no. 9, pp. 3322-3332, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/TCYB.2018.2841847.

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

Sutrisno Ibrahim, currently a lecturer and chairman in the Electrical Engineering Department, Sebelas Maret University, Surakarta. Graduated from the Electrical Engineering study program (S.T.) from the Sepuluh Nopember Institute of Technology, Indonesia. For the master's and doctoral programs from King Saud University, Saudi Arabia. Fields of expertise: Artificial intelligence and biomedical engineering. Email: sutrisno@staff.uns.ac.id, and Researcher website (Scopus, Google Scholar, or Orcid). |

|

Faisal Rahutomo, currently a lecturer in the Electrical Engineering Department, Sebelas Maret University, Surakarta. Graduated from the Electrical Engineering study program (S.T.) Brawijaya University, Indonesia. For the master's program (M.Kom) obtained from the Sepuluh Nopember Institute of Technology, Indonesia and for the doctoral from Kumamoto University, Japan. Fields of expertise: Software Engineering, Data & Knowledge Engineering.

Email: faisal_r@staff.uns.ac.id, and Researcher website (Scopus, Google Scholar, or Orcid) |

|

Reihan Dhimas Putra Henda, Graduated from Electrical Engineering Department Universitas Sebelas Maret. Email: reihan_henda@student.uns.ac.id |

|

Majid Aljalal, he is currently a researcher in the Electrical Engineering Department, King Saud University, Saudi Arabia. Graduated for master's and doctoral programs from King Saud University also. |

Sutrisno Ibrahim (Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms with Feature Engineering for Epileptic Seizure Prediction Based on Electroencephalogram (EEG) Signals)