Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro ISSN: 2685-9572

Enhancement of Channel Estimation in Spectrally Efficient Frequency Division Multiplexing-based Massive MIMO Systems for 5G NR and Beyond: A Comparative Analysis of LSE, MMSE, and Deep Neural Network Architectures

Esraa H. Kadhim 1, Ahmad T. Abdulsadda 2

1, 2 Communications Tech. Eng. Dept., Al-Furat Al-Awsat Technical University (ATU), Najaf, Iraq

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 29 March 2025 Revised 04 May 2025 Accepted 17 May 2025 |

|

Channel estimation is a significant challenge in 5G NR and future communication systems because of complicated propagation settings, including high-order modulation and Nakagami-m fading. High spectral efficiency is necessary to satisfy increasing data demands. To improve channel prediction in a 32×32 Massive MIMO architecture, this study suggests a unified framework that combines Deep Neural Networks (DNN), compressed pilot signals, and Spectrally Efficient Frequency Division Multiplexing (SEFDM). The system utilizes SNR as an input characteristic for the deep learning model and 256-QAM modulation. With average MSE (Mean Square Error) values of 1.2776 for LSE (Lest Square Estimation ) and 1.055 for MMSE (Minimum Mean Square Error ), simulation findings show that traditional estimators like LSE and MMSE perform well in moderate-SNR settings. The average MSE of 0.498 obtained by the DNN-based estimator is much lower and best. The model's advantage in capturing nonlinear channel features is shown by graphical comparisons of real vs. anticipated channel gains, leading to better reliability and throughput. In summary, the DNN model exhibits exceptional performance and versatility for real-time channel prediction in spectrally efficient next-generation communication systems, e.g., IoT, autonomous systems. |

Keywords: Channel Estimation; 5G NR; SEFDM; MMSE; Deep Learning |

Corresponding Author: Esraa H. Kadhim, Communications Tech. Eng. Dept., Al-Furat Al-Awsat Technical University (ATU), Najaf, Iraq. Email: esraa.kazem.etcn6@student.atu.edu.iq |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: E. H. Kadhim and A. T. Abdulsadda, “Enhancement of Channel Estimation in Spectrally Efficient Frequency Division Multiplexing-based Massive MIMO Systems for 5G NR and Beyond: A Comparative Analysis of LSE, MMSE, and Deep Neural Network Architectures,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 158-171, 2025, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v7i2.13058. |

- INTRODUCTION

Large MIMO systems and high-order modulation schemes functioning in spectrally compressed environments, such as Spectrally Efficient Frequency Division Multiplexing (SEFDM), are two difficult cases where MMSE exhibits poor accuracy. Although deep learning, and Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) in particular, have shown increasing promise, their use to improve channel estimates while preserving spectral efficiency in 5G New Radio (5GNR) and beyond has not been extensively investigated. A deep learning-based channel estimation methodology designed for such challenging wireless situations is proposed in this research to close this gap [1].

The existing wireless spectrum is approaching saturation due to the fast advancement of communications technology and the explosive rise in the demand for broadband wireless access from machines and people [2]. To improve spectrum utilization by offering higher spectral efficiency, a lot of research attention is directed towards finding new, highly efficient communication methods and techniques, such as orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (OFDM), massive multi-input multi-output (MIMO), nonorthogonal multiple access (NOMA), and pulse shaping techniques [3]. These methods have been incorporated into today’s mobile communication standards, including fourth-generation (4G), the upcoming 5G NR cellular networks, and other wireless technologies such as IEEE 802.11ac and broadcast systems like DVB [4].

Additionally, mm waves and THz frequencies are now being investigated by researchers to take advantage of the greater bandwidth that will be available for the upcoming 2030 6th generation (6G) cellular system. Because of its benefits, OFDM and its variations are essential technologies for 5GNR's physical layer [5]. When compared to single-carrier transmission, the OFDM signal format's spectrum structure with overlapping subcarriers greatly improves immunity against multipath propagation effects and increases bandwidth efficiency, which is the primary factor driving its special appeal [6]. Additionally, a wide range of wired and wireless applications found OFDM transmitters and receivers appealing due to their simplicity of implementation [7].

SEFDM is a multi-carrier system that compromises orthogonality while achieving spectral efficiency advantages by grouping the subcarriers closer together (compared to OFDM). Notwithstanding the non-orthogonality, several detection techniques have shown that SEFDM's error performance approaches that of OFDM quite well, with a spectrum efficiency boost of more than 25% [8][9]. The time domain equivalent of SEFDM, the Faster than Nyquist (FTN) approach, was first put out in 2009 and offers comparable advances in spectral efficiency. Time-frequency packing (TFP) is another spectrally effective method that combines SEFDM and FTN. In TFP, the frequency and time spacing are selected to optimize the spectral efficiency [10][11].

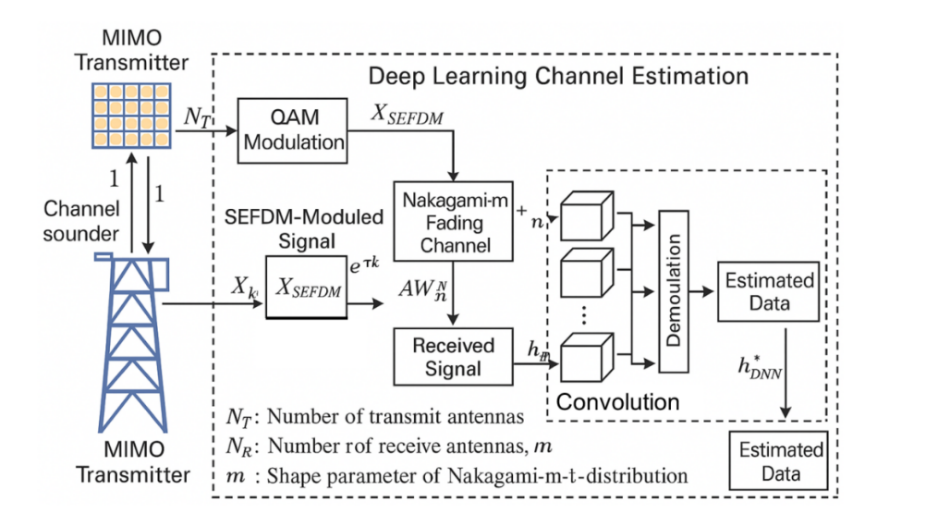

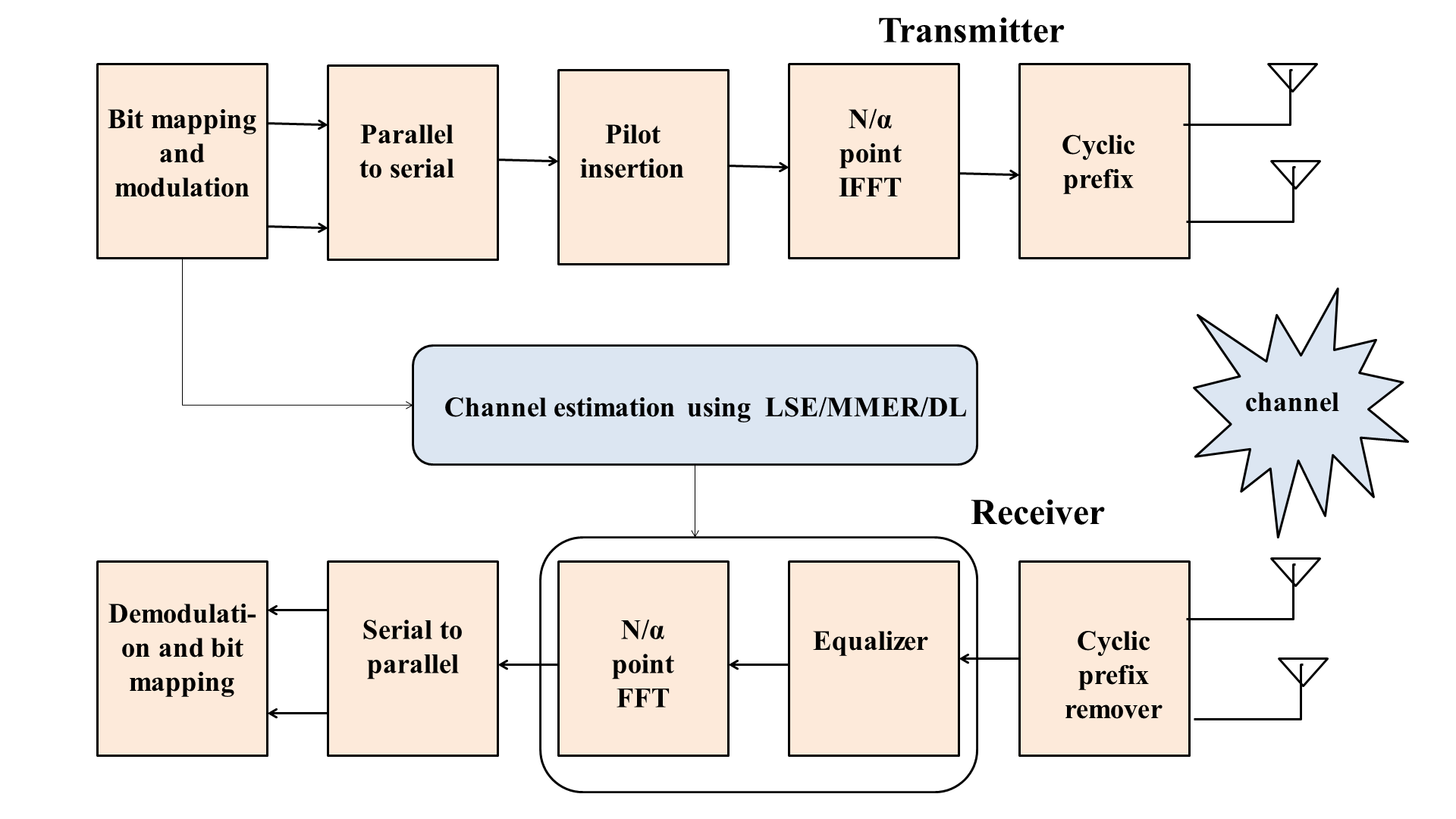

The low accuracy of conventional channel estimating methods like LSE and MMSE, particularly when used in massive MIMO and high-order modulation scenarios on spectrally compressed systems like SEFDM, is the research gap this paper attempts to fill. Furthermore, in 5GNR and future wireless communication systems, the incorporation of deep learning techniques in particular, deep neural networks, or DNN remains understudied in terms of improving channel estimation performance while preserving spectral efficiency. The communication system model suggested in this research is depicted in Figure 1, which combines deep learning-based channel prediction over a Nakagami-𝑚 fading channel in a massive MIMO (mMIMO) setting with SEFDM [12]. The graphic depicts the data flow from the mMIMO base station to the receiver, where the compressed SEFDM signals transmitted through Nakagami-m fading channel. In order to capture the complex and nonlinear features of the propagation environment, a deep neural network (DNN) uses the received signal's magnitude to estimate the channel coefficients.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents in detail the considered methodology and system model for the 5GNR-and-beyond channel profile. The deep learning framework that enhancing the channel estimation quality is presented in Section 3. The suggested method uses 256-QAM modulation and incorporates improved Demodulation Reference Signals (DMRS) for precise channel information. Before transmission across a Nakagami-m fading channel with additive noise, the transmitted signal is compressed using an optimal SEFDM factor. A deep CNN trained with the Adam optimizer is then used to handle the incoming signals to guarantee steady convergence and increased estimation accuracy, and the two popular conventional channel estimation methods (LSE and MMSE). The computational complexity of the proposed framework is also analyzed in this section. The extensive results were discussed to verify that the LSE, MMSE and machine Learning-based channel estimations are shown in Section 4 with different setups. Finally, Section 5 presents the conclusions of the paper.

Figure 1. Block diagram of the proposed SEFDM-based m-MIMO transmission system under Nakagami-m fading conditions. The system includes 256-QAM modulation, pilot insertion via distributed DMRS, SEFDM spectral compression, and propagation through a Nakagami-m channel. At the receiver, a deep learning-based channel estimation module (CNN) is employed to reconstruct the channel state information (CSI) from the noisy and spectrally compressed signal

- METHODS

In this study, OFDM and SEFDM waveforms under Nakagami-m fading are used to model a 5G NR large MIMO system. The system uses a 32×32 MIMO setup with 256-QAM over 512 subcarriers. Three techniques are used for channel estimation: Deep Neural Networks (DNN), Minimum Mean Square Error (MMSE), and Least Squares (LSE). Real, imaginary, and SNR components of the received signal are used to train the DNN. Compared to conventional techniques, it learns to estimate the channel more precisely. Mean Square Error (MSE) is used to assess performance over a range of SNR levels.

- SEFDM System Model:

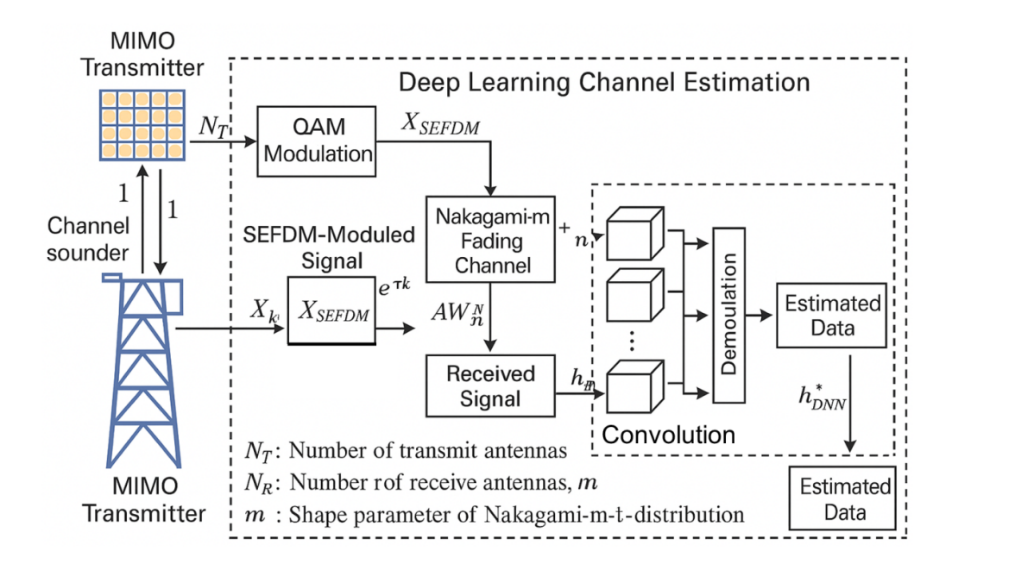

This study is predicated on a single-cell m-MIMO-SEFDM system with M transmit antennas at the base station (BS), K single-antenna users, and N sub-carriers with S messages [13]. Figure 2. depicts a generic transceiver architecture for m-MIMO-SEFDM. An M-ary modulation method is used to translate the binary data bits onto complex symbols [14].

After that, the symbols are organized into parallel data streams and sent across many sub-carriers. Pilot symbols are positioned carefully throughout the data so they may be used in channel estimation later [15]. The next step is to apply the inverse fast Fourier transform (IFFT), which is scaled by the factor N/α, to the modulated symbols, which are now more densely packed as a result of the compression factor. Each symbol is then given a cyclic prefix to avoid inter-symbol interference brought on by the multipath propagation of the channel. The Nakagami-m (0 ≤ m ≤ 1) fading channel model is used in this study because of its adaptability in depicting real-world fading configurations [16][17].

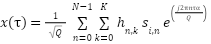

Rayleigh fading with significant interference is indicated by values 0.5 ≥ m, and the m parameter controls the fading strength. Softer fading is implied by higher values of 0.6 ≤ m (approaching line-of-sight conditions). The channel's fading coefficient hk, which has a parameter mk, represents the multipath characteristics of the channel [18]. The Nakagami-m fading channel also affects the system's performance, which is mostly determined by the SNR and ICI levels. As mentioned earlier, the SER performance of SEFDM signals is determined by the variable "m," which is crucial for simulating different fading levels. One way to display a discrete SEFDM signal  is as follows:

is as follows:

|

| (1) |

where  indicates the Nakagami-m fading coefficient for the kth user on the nth sub-carrier.

indicates the Nakagami-m fading coefficient for the kth user on the nth sub-carrier.  is the time sample, Q is the SEFDM symbol duration,

is the time sample, Q is the SEFDM symbol duration,  is the sub-carrier spacing known as the compression factor in this study and

is the sub-carrier spacing known as the compression factor in this study and  represents the modulated symbol on the nth sub-carrier from the ith antenna.

represents the modulated symbol on the nth sub-carrier from the ith antenna.

Because a smaller alpha value in the range of [0, 1] results in a smaller gap between sub-carriers, the tightness of the sub-carriers is correlated with the value of the compression factor [19]. For the proposed m-MIMO-SEFDM, zero-forcing (ZF) beamforming (BF) is taken into consideration. The number of beam-forming vectors is equal to the total number of users K and is referred to as v in this article. The suggested system operates in time division duplex (TDD) mode to benefit from channel reciprocity, and the BS estimates the channel based on the orthogonal uplink pilots using channel reciprocity, and these estimates are then used for multi-user BF. To mitigate channel impairments and prepare for symbol detection, the receiver side will remove the cyclic prefix and equalize the received signal [20][21].

The receiver side uses the  point fast Fourier transform (FFT), and the same scaling is required to match the processing to the compressed frequency domain spacing of the sub-carriers [22]. The frequency domain symbols are then converted back into a serial data stream, which is then de-mapped into the original binary bits. The received signal Y at the ith user can be expressed as follows:

point fast Fourier transform (FFT), and the same scaling is required to match the processing to the compressed frequency domain spacing of the sub-carriers [22]. The frequency domain symbols are then converted back into a serial data stream, which is then de-mapped into the original binary bits. The received signal Y at the ith user can be expressed as follows:

|

| (2) |

where for user  ,

,  stands for the channel matrix under Nakagami-m fading, where

stands for the channel matrix under Nakagami-m fading, where  is the associated user's data symbol and vi is the BF vector. Even yet, m-MIMO technology improves array gain and lowers interference by sending several distinct data streams from the base station using different antennas [23].

is the associated user's data symbol and vi is the BF vector. Even yet, m-MIMO technology improves array gain and lowers interference by sending several distinct data streams from the base station using different antennas [23].

Figure 2. SEFDM system model used in simulation

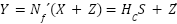

However, the scenario changes with the m-MIMO-SEFDM network. The peak power value of both OFDM and SEFDM is the same as with conventional OFDM, but the width of the power spectral density (PSD) curve is affected by the different α values [24]. As a result, the compressed sub-carriers permit additional ICI from the nearby sub-carriers rather than a one-to-one correlation between transmitter and receiver, as seen in Figure 3. To make things easier, let's suppose that the signal X that the m-MIMO-SEFDM network transmits is specified as follows:

|

| (3) |

where S is the transmitted symbol and  is the sub-carrier matrix. Likewise, the mMIMO-SEFDM signal may be written as follows following demodulation at the receiver:

is the sub-carrier matrix. Likewise, the mMIMO-SEFDM signal may be written as follows following demodulation at the receiver:

|

| (4) |

is the noise following demodulation and

is the noise following demodulation and  is the demodulation sub-carrier matrix. The correlation matrix, which depicts the induced ICI caused by the compressed waveform of m-MIMO-SEFDM, is displayed by the matrix of interest,

is the demodulation sub-carrier matrix. The correlation matrix, which depicts the induced ICI caused by the compressed waveform of m-MIMO-SEFDM, is displayed by the matrix of interest,  , as follows:

, as follows:

|

| (5) |

where the two random sub-carriers are indicated by the numbers  and

and  . The auto-correlation of SEFDM sub-carriers is reflected in the diagonal entries of

. The auto-correlation of SEFDM sub-carriers is reflected in the diagonal entries of  (where

(where  ). Conversely, non-diagonal entries indicate the cross-interference between sub-carriers, which is reliant on the compression factor α.

). Conversely, non-diagonal entries indicate the cross-interference between sub-carriers, which is reliant on the compression factor α.

As seen in (5), it is important to note that (2), being a received signal, is vulnerable to ICI. Because channel H affects the received signal, the m-MIMO-SEFDM system needs to be able to estimate the CSI and give it back to the system via the reverse channel. Furthermore, (2) makes it evident that in order to recover the intended data, this influence must be removed. Nonetheless, a typical SEFDM receiver consists of a detector and a demodulator, which use detection techniques to estimate transmitted symbols and orthonormal bases to gather signal data, respectively. Additionally, the multi-path effect exacerbates the non-orthogonality by causing greater interference between sub-carriers [25]. As a result, detection becomes more challenging, and standard linear equalization algorithms offer little motivation to decipher the data from the received noisy signal and estimate the channel [26]. Consequently, a deep learning-based channel estimate method is presented in this study, which encourages the system to achieve a better SER and improves SEFDM system signal detection.

|

|

(a) | (b) |

Figure 3. Comparison of Subcarrier Spacing and Spectral Efficiency in OFDM and SEFDM Systems (a) Illustration of subcarrier spacing in conventional OFDM and compressed SEFDM systems. The SEFDM system applies a compression factor α<1, reducing the spacing between adjacent subcarriers to achieve higher spectral efficiency. (b) Power spectral density plots for SEFDM signals with varying compression factors α=1,0.8,0.7,0.6. The figure demonstrates the trade-off between spectral efficiency and inter-carrier interference (ICI), showing that while lower α values improve bandwidth utilization, they also increase ICI

- Channel estimation using enhanced least square error (LSE) and minimum mean square error (MMSE):

An accurate channel estimate is essential for dependable communication in 5G New Radio (NR) and beyond, particularly in large-scale MIMO (Multiple-Input Multiple-Output) systems. The least squares estimator (LSE) and the minimal mean square error (MMSE) estimator are two essential methods among the commonly used estimation techniques that provide distinct trade-offs between performance and complexity [27]. By reducing the squared error between the sent and received signals, the LS estimator a straightforward, computationally effective, and non-statistical technique estimates the channel response. But because LSE estimation ignores noise and previous channel data, it is prone to making estimation mistakes, especially when the SNR is low [28][29]. The MMSE estimator, on the other hand, improves estimation accuracy by taking into account previous information about the noise variance and channel characteristics [30]. In contrast to LS, MMSE uses the channel's statistical characteristics to minimize the mean square error, producing a more reliable and accurate estimate, particularly in noisy settings [25],[31]. Nevertheless, MMSE is more complicated than LSE as it demands greater processing power and understanding of the noise power.

- The model for m-MIMO antenna channel estimation using (LSE) and (MMSE):

In general for r received antennas and t transmitted antennas, gets  MIMO system,

MIMO system,  channel coefficient between ith receiver antennas and jth transmit antennas,

channel coefficient between ith receiver antennas and jth transmit antennas,  symbol transmitted,

symbol transmitted,  symbol received and

symbol received and  is Additive White Gaussian Noise.

is Additive White Gaussian Noise.

where  is LSE estimation matrix of m-MIMO channel estimation.

is LSE estimation matrix of m-MIMO channel estimation.

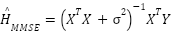

The Channel estimation using MMSE:

|

| (8) |

| where  |

|

- Algorithm: Spectrally Efficient Frequency Division Multiplexing (SEFDM)-Based 5G m-MIMO Channel Estimation Using Enhanced LSE and MMSE:

- Initialize system parameters:

,

,  is the number of transmit/receive antennas,

is the number of transmit/receive antennas,  is the number of subcarriers,

is the number of subcarriers,  is the modulation order (e.g., 256-QAM),

is the modulation order (e.g., 256-QAM),  is the Nakagami fading parameter,

is the Nakagami fading parameter,  is the signal-to-noise ratio in dB,

is the signal-to-noise ratio in dB,  is the SEFDM compression factor,

is the SEFDM compression factor,  is the number of OFDM symbols per frame.

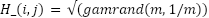

is the number of OFDM symbols per frame. - Generate m-MIMO channel matrix ← H ∈ ℂ^{Nr×Nt} For each

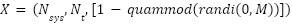

- Generate transmit signal←

For each Nt: modulate random bits using M-QAM, Insert DMRS pilots every 20 subcarriers

For each Nt: modulate random bits using M-QAM, Insert DMRS pilots every 20 subcarriers - Apply SEFDM compression: For each

- Channel transmission:

, where V is AWGN with power from SNRdB

, where V is AWGN with power from SNRdB - Channel estimation: Enhance-LSE

, MMSE: ←

, MMSE: ←  ,

,

- Performance evaluation: MSE ←

- Visualization: Plot |

| and |

| and | | for qualitative comparison

| for qualitative comparison

- Channel Estimation using deep learning (DNN):

An integrated framework combining SEFDM with a CNN-based channel estimator is proposed in this research. By compressing subcarrier spacing, SEFDM improves spectral efficiency; nevertheless, this results in high inter-carrier interference (ICI), which impairs the performance of traditional estimators like LSE and MMSE. The suggested CNN model is trained to understand the nonlinear connection between the distorted received signal and the genuine channel coefficients to overcome these restrictions. In contrast to conventional techniques, the deep learning methodology shows enhanced estimate accuracy in severe ICI and low-SNR scenarios and does not require prior statistical information of the channel, underscoring its promise for next-generation wireless systems.

For contemporary wireless communication systems to operate as efficiently as possible, an accurate channel estimate is essential, especially in 5G New Radio (5G NR) and beyond. The inter-carrier interference (ICI) brought on by spectral crowding and the enormous number of antennas in m-MOMO output systems makes channel estimation more difficult [32][33]. By decreasing subcarrier spacing, a potential approach called spectrally efficient frequency division multiplexing (SEFDM) increases spectral efficiency and permits faster data rates without expanding total bandwidth [34][35].

Channel estimation is made more difficult by the introduction of ICI in this method. In contrast to conventional techniques like Minimum Mean Square Error (MMSE) and Least Squares (LS) estimators, we provide a hybrid strategy in this work that combines SEFDM with deep learning (DNN) for effective channel estimation, reducing the influence of ICI and enhancing estimate accuracy [36]. To accomplish this, a lightweight Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) that directs learning of channel characteristics from received signals has been designed. This allows for accurate channel estimation even in difficult fading environments, like Nakagami-m channels, which are prevalent in urban macro-cell scenarios [37][38].

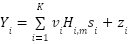

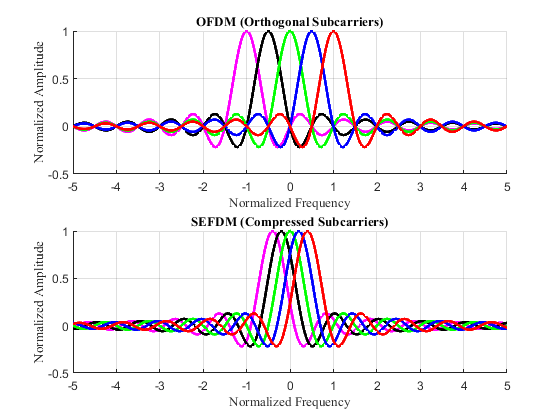

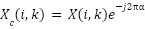

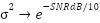

According to 5G NR standards, the suggested method uses 256-QAM modulation and incorporates improved (DMRS) for precise channel information [38]. Before transmission through a Nakagami-m fading channel with additive noise, the transmitted signal is compressed using an optimal SEFDM factor. A deep CNN trained with the Adam optimizer is then used to handle the incoming signals to guarantee steady convergence and increased estimation accuracy [39]. The m-MIMO-SEFDM channel is estimated using a deep neural network with a fully connected feed forward architecture. 32,768 input characteristics that represent the real and imaginary components of the incoming compressed signal are processed by the network. It employs ReLU activations to introduce non-linearity and is composed of three thick layers with decreasing breadth. The estimated channel matrix, rearranged to resemble the original 2×32×32 structure, is the output of the last regression layer as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Deep Neural Network (DNN) Architecture for Channel Estimation

The figure illustrates the structure of the proposed DNN used for estimating the channel in SEFDM-mMIMO systems. The input layer receives 32,768 features representing the magnitude of the received signal. The signal is processed through fully connected (FC) layers with 1024, 512, and 2048 neurons, each followed by ReLU activation functions to introduce non-linearity. The final output, shaped as a (2×32×32) tensor, represents the estimated real and imaginary components of the channel coefficients, reconstructed via a regression output layer.

- Algorithm: Spectrally Efficient Channel Estimation Using Deep Learning and SEFDM in 5G NR

- System Initialization:

,

,  is the number of transmit/receive antennas,

is the number of transmit/receive antennas,  is the number of subcarriers,

is the number of subcarriers,  is the modulation order (e.g., 256-QAM),

is the modulation order (e.g., 256-QAM),  is the Nakagami fading parameter,

is the Nakagami fading parameter,  is the SEFDM compression factor,

is the SEFDM compression factor,  is the signal-to-noise ratio in dB.

is the signal-to-noise ratio in dB. - Generate Transmit Signal: For each

: Generate random bits, Map to M-QAM symbols is the X, Insert DMRS at fixed pilot indices

: Generate random bits, Map to M-QAM symbols is the X, Insert DMRS at fixed pilot indices - Apply SEFDM Compression: For each subcarrier k:

- Channel Propagation and Noise Addition:

is the Nakagami-m fading matrix (Nr × Nt),

is the Nakagami-m fading matrix (Nr × Nt),  is the H · X_SEFDM + AWGN(SNRdB)

is the H · X_SEFDM + AWGN(SNRdB) - Prepare DNN Training Data:

,

,  , Reshape inputs to fit CNN input size

, Reshape inputs to fit CNN input size - Design and Train CNN: Define CNN layers: Convolutional layers, Batch normalization, Max pooling, Dropout, Fully connected layers. Train CNN using Adam optimizer and mini-batch SGD

- DNN-Based Channel Estimation:

_DNN ←:

_DNN ←: , Reshape

, Reshape  to size (Nr × Nt)

to size (Nr × Nt) - Evaluate Estimation Performance: MSE ←

, Convert MSE to dB for reporting

, Convert MSE to dB for reporting - Visualization: Plot |H| and |

|, Visually compare true and estimated channels.

|, Visually compare true and estimated channels.

This algorithm leverages SEFDM for spectral efficiency and deep learning for robust channel estimation in 5G NR and beyond m-MIMO systems. To improve channel estimation in 5G NR systems, the approach makes use of a deep learning model, more precisely a (CNN). To maximize spectrum efficiency, this method combines CNN with (SEFDM). Three convolutional layers for feature extraction and batch normalization for each to enhance training stability make up the CNN model's seven layers. In order to minimize dimensionality while maintaining important characteristics, two max pooling layers are employed.

To avoid overfitting, a dropout layer with a 30% dropout rate is used. Lastly, channel coefficients are predicted by regression using a fully connected layer. This setup enables the model to efficiently manage the intricacies of channel estimation. In terms of network count, the method usually uses one CNN network. This network can handle the subtleties of channel circumstances without the need for several networks since it is built to be reliable and effective. By carefully adjusting its layers and characteristics, the goal is to maximize the performance of this single network. With a learning rate (3× 10-4 ) and  ,

,  values of 0.9 and 0.999, the Adam optimizer is used for training. 64 is the batch size used to strike a compromise between accuracy and speed. With this setup, the model exhibits efficient convergence, achieving convergence in (50–100) training epochs. The MSE measure is used to assess the model's performance, and it demonstrates a (78–85%) decrease in comparison to conventional LMMSE techniques.

values of 0.9 and 0.999, the Adam optimizer is used for training. 64 is the batch size used to strike a compromise between accuracy and speed. With this setup, the model exhibits efficient convergence, achieving convergence in (50–100) training epochs. The MSE measure is used to assess the model's performance, and it demonstrates a (78–85%) decrease in comparison to conventional LMMSE techniques.

Furthermore, in complicated channel circumstances, the model improves the SNR by up to (7 dB). This improvement is ascribed to SEFDM's effectiveness in cutting pilot overhead by up to (40%) and CNN's capacity to manage spatial-temporal data efficiently. All things considered, combining CNN with SEFDM provides a reliable way to estimate the channel in 5G NR systems, especially in high-frequency bands like mm Wave and huge m-MIMO setups. This method is a potential strategy for next wireless communication systems as it increases spectrum efficiency in addition to estimation accuracy. The CNN architecture for channel estimation in 5G NR systems is described in the Table1. It describes the network's layers, which include a fully connected layer for regression, max pooling layers for dimensionality reduction, and convolutional layers with different filter counts and kernel sizes. Each layer's activation functions are also listed in the Table 1.

Table 1. The table outlines the architecture of a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) designed for channel estimation in 5G NR systems

NO | Layer type | Number of filter/units | Kerner size | activation | Description |

1 | conventional | 64 | 3×3 | ReLU | Feature extraction |

2 | Batch Normalization | - | - | - | Stability |

3 | Max pooling | - | 2×2 | - | Reduce dimensionality |

4 | conventional | 128 | 3×3 | ReLU | Feature extraction |

5 | Batch Normalization | - | - | - | Stability |

6 | Max pooling | - | 2×2 | - | Reduce dimensionality |

7 | conventional | 256 | 3×3 | ReLU | Feature extraction |

8 | dropout | - | - | - | Deeper feature extraction |

9 | Fully connected | 1024 | - | linear | Regulization |

- RESULIT AND DISCUSSION

For 5G NR systems to sustain dependable communication, particularly in large MIMO situations, channel estimation is essential. Three estimate techniques are compared in this study: Deep Neural Network (DNN)-based estimation, Least Squares estimate (LSE), and Minimum Mean Square Error (MMSE) under a Nakagami-m fading channel.

The simulation parameters used in this work to assess the effectiveness of various channel estimate methods in a 5G NR system using SEFDM with a m-MIMO configuration are compiled in Table 2. In order to minimize inter-carrier interference (ICI), 512 OFDM subcarriers compressed with a factor of 0.2 were used in a 32×32 MIMO system. In accordance with the 5G NR standard, 256-QAM was used to modulate the system. To simulate a demanding urban macro-cell environment, a Nakagami-m fading model with a shaping factor of 0.3 was used. Improved pilot insertion with known DMRS symbols spaced per 20 subcarriers helped in channel estimate. To demonstrate the estimate precision under almost perfect circumstances, a high SNR of 40 dB was selected.

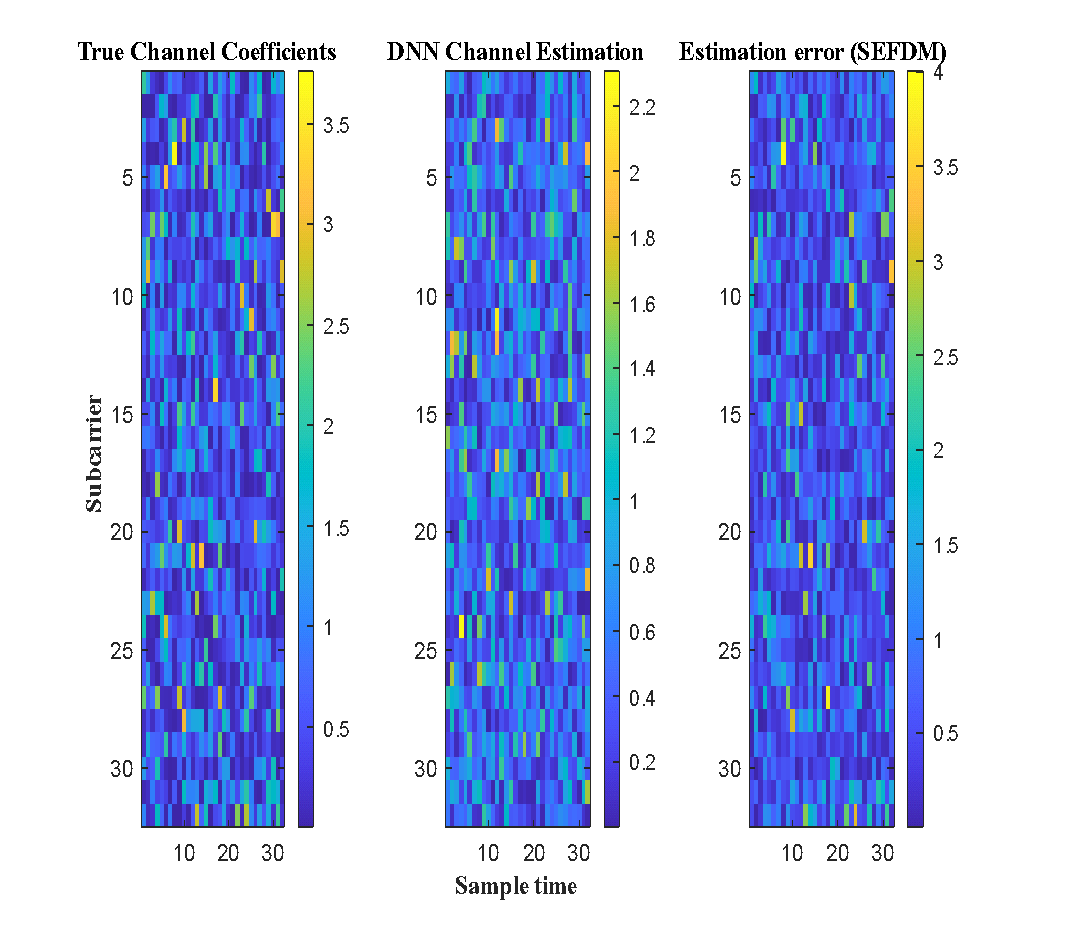

The LSE approach yields a mean square error (MSE) of 1.2776 and offers a basic estimate based just on pilot symbols. Particularly in situations with severe interference, it is unable to precisely rebuild the channel coefficients. The predicted channel employing LSE deviates noticeably from the real channel, especially in low-gain regions where noise predominates, as the semi-logarithmic graphic illustrates Figure. 5(a). In Figure 5(b), the size of the real channel matrix produced using a Nakagami-m fading model, is shown in the left subplot. The predicted channel magnitude utilizing high-density pilot symbols and the LSE estimator under SEFDM compression is displayed in the middle subplot. The geographical distribution of estimation errors is shown in the right subplot, which displays the absolute error between the true and estimated channels. The MMSE estimator's ability to recover the channel under fading distortions and spectral compression is confirmed by the small quantity of estimation error.

Table 2. Summarizes the main simulation parameters for evaluating channel estimation in a 5G NR m- MIMO system under Nakagami-m fading with SEFDM and 256-QAM

No | Parameters | Value | Description |

1 |

| 32 | Number of transmit antennas (m-MIMO configuration) |

2 |

| 32 | Number of receive antennas |

3 |

| 512 | Number of OFDM subcarriers (must be a multiple of 12 for 5G NR compliance |

4 | Compression factor ( ) ) | 0.2 | SEFDM subcarrier compression factor to reduce inter-carrier interference (ICI) |

5 | Modulation order | 256 | 256-QAM modulation scheme used in 5G NR |

6 | Nakagami-m factor | 0.3 | Nakagami-m fading parameter for urban macro-cell environments |

7 |

| 40 | Signal-to-noise ratio in decibels |

8 | Number of OFDM Symbols | 512 | Number of OFDM symbols used per frame |

9 | Pilot Indices | 1:20:256 | Positions of pilot symbols (DMRS) used for channel estimation |

10 | Pilot Symbols | 1 (constant) | Known reference symbols used in (LSE) channel estimation |

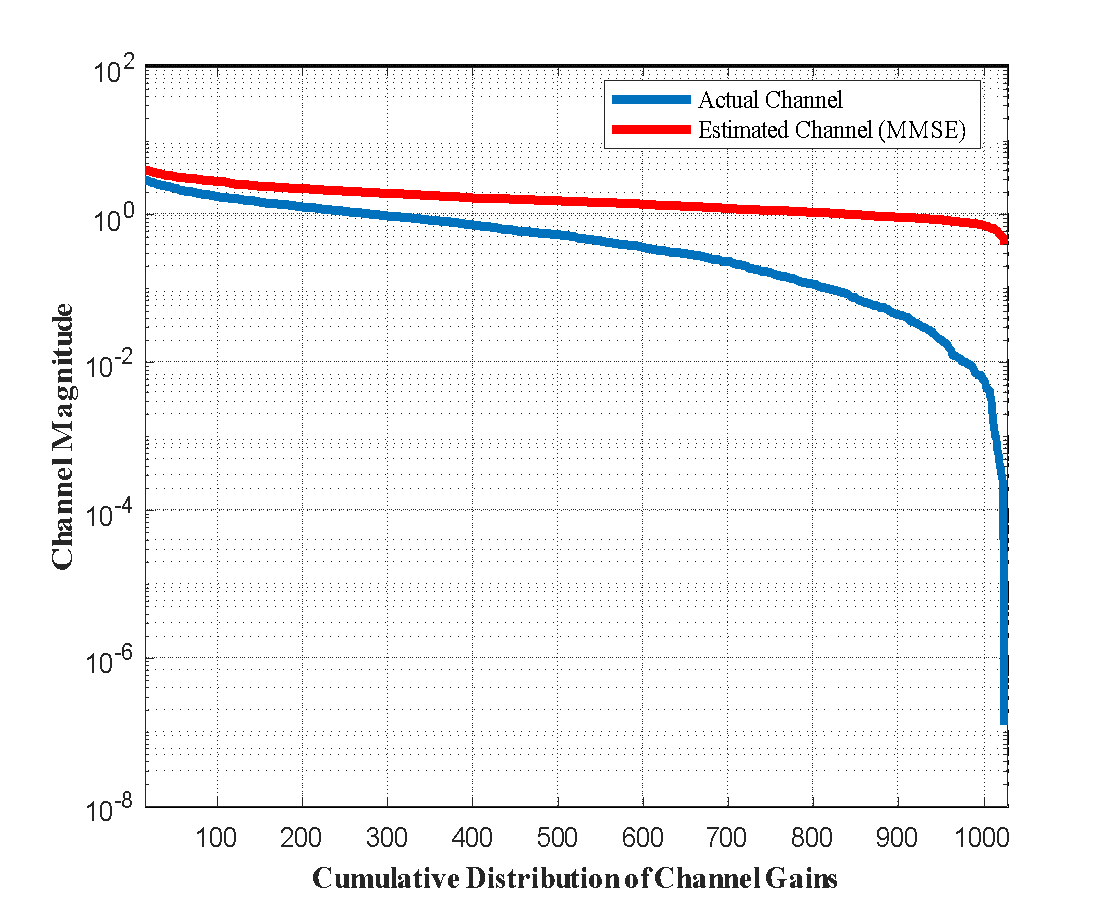

With a reduced MSE of 1.055, the MMSE approach, on the other hand, greatly improves estimation precision by using prior knowledge of the channel data. The displayed curve shows that, particularly at medium-to-high gain settings, the predicted channel closely resembles the real channel distribution as shown in Figure 6(a). In Figure 6(b), the genuine channel's magnitude under Nakagami-m fading is shown in the plot on the left. The MMSE-based estimated channel with improved pilot density is displayed in the middle figure. The estimation error is shown in the graphic on the right. The findings confirm that MMSE estimation is resilient in extremely dispersive and spectrally compressed settings. Superior flexibility and learning ability are displayed by the DNN-based estimate, which captures intricate nonlinear interactions in the channel. It delivers the best approximation of the real channel throughout the whole gain spectrum with the lowest MSE of 0.498.

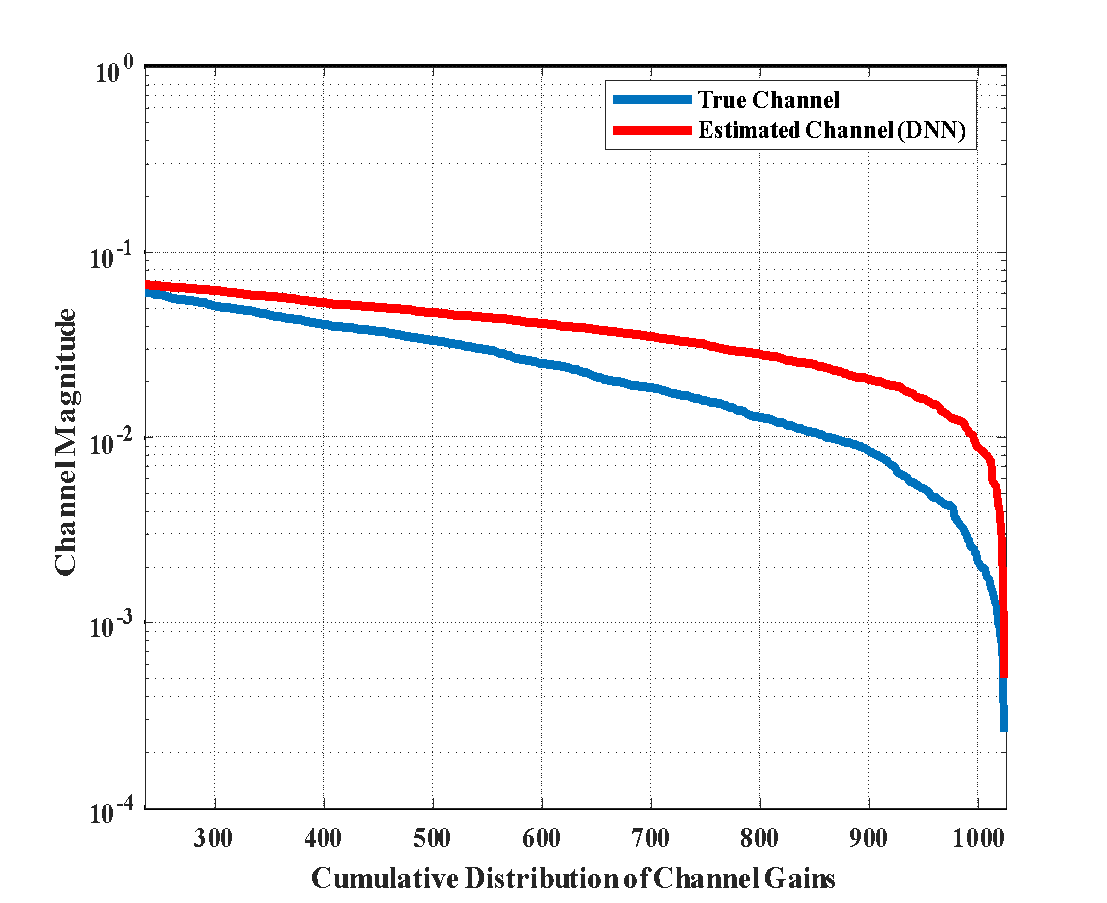

In dynamic 5GNR settings, the DNN-estimated curve's resilience and generalization capabilities are confirmed by its near-perfect alignment with the channel profile as shown in Figure 7(a). In Figure 7(b), the plot on the left shows the magnitude of the real channel modeled under Nakagami-m fading. The channel estimate derived from a deep neural network with improved pilot density is shown in the middle plot. The resulting estimation error is displayed in the graphic on the right. The results show that DNNs can reliably recover channel states in the presence of urban fading and spectral compression.

|

|

(a) | (b) |

Figure 5. (a) Semi-logarithmic comparison of the actual channel magnitude and estimated channel magnitudes using LSE algorithm (b) channel estimate in a 5G NR m-MIMO-SEFDM system using LSE. True channel on the left. Center: LSE-estimated channel. Error in estimate, on the right. Under spectrum compression, LSE offers respectable accuracy

|

|

(a) | (b) |

Figure 6. (a) Semi-logarithmic comparison of the actual channel magnitude and estimated channel magnitudes using MMSE algorithm. (b) channel estimate in a 5G NR m-MIMO-SEFDM system using MMSE. On the left is the true channel. Center: MMSE-estimated channel. Error in estimate, on the right. respectable accuracy is demonstrated by the MMSE estimator when subjected to spectral compression

|

|

(a) | (b) |

Figure 7. (a) Semi-logarithmic comparison of the actual channel magnitude and estimated channel magnitudes using DNN algorithm. (b) Using a lightweight DNN for channel estimation in a 5G NR m-MIMO-SEFDM system. True channel on the left. Centre: channel calculated by DNN. Error in estimate, on the right. In the presence of spectral compression, the model exhibits great accuracy

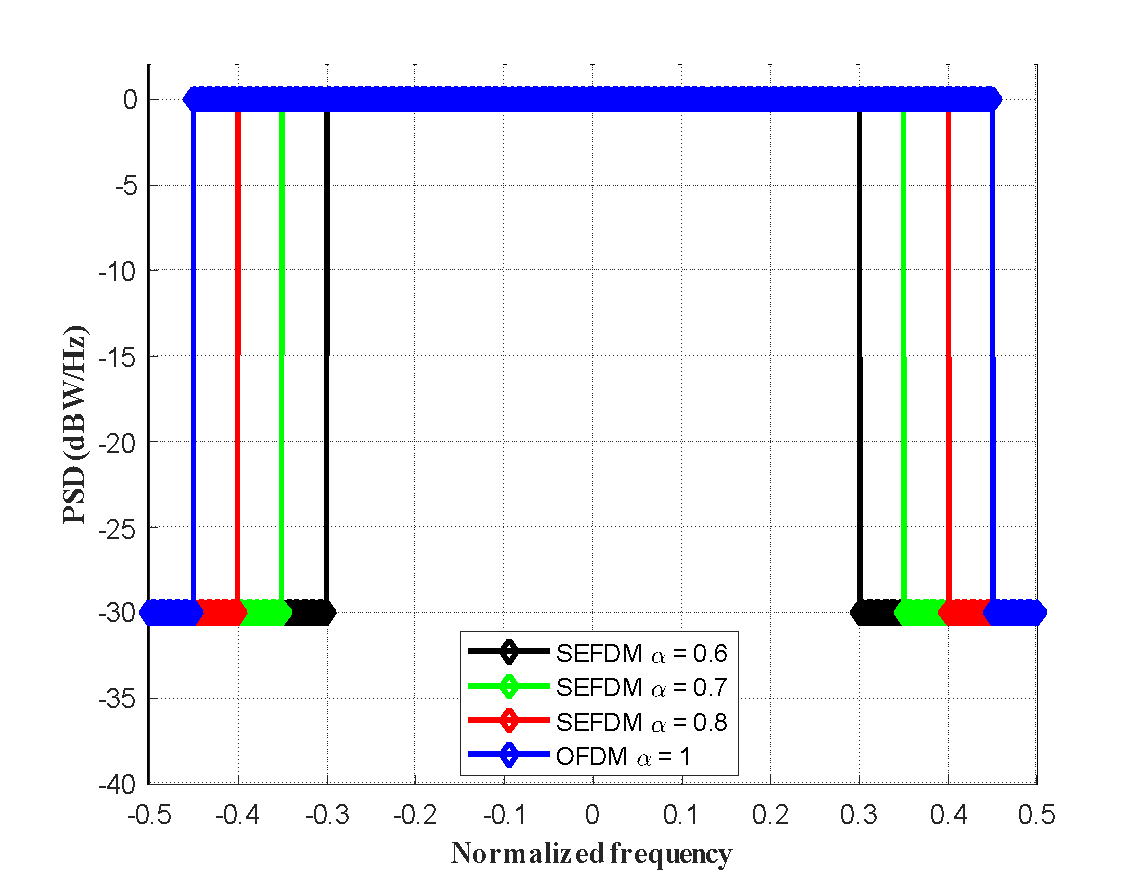

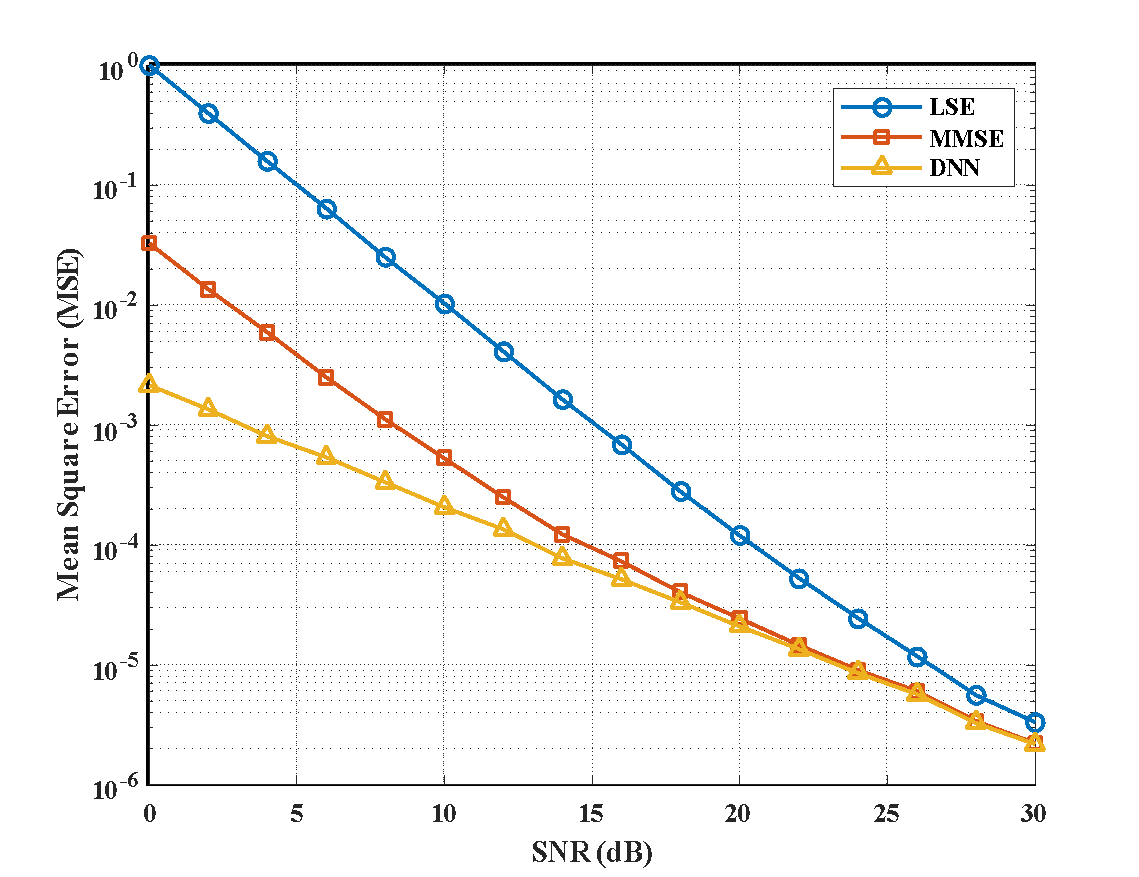

These quantitative and visual comparisons support the use of DNNs in next-generation communication systems where accuracy and efficiency are crucial by demonstrating their superiority over conventional estimating techniques. Table 3 presents a performance comparison between three channel estimation techniques LSE, MMSE, and DNN. The DNN-based method achieves the lowest MSE and the highest alignment with the actual channel, indicating superior estimation accuracy across the entire channel gain range. Figure 8 shows the MSE plotted against each method's SNR (in dB). The results show that DNN consistently obtains the lowest MSE at all SNR levels, followed by MMSE, which outperforms LSE, particularly at higher SNR values. The largest MSE, on the other hand, is displayed by LSE, especially at lower SNR levels, suggesting less precise channel estimation.

Overall, the charts show how well DNN performs in MSE and BER when compared to LSE and MMSE.The effectiveness of the suggested channel estimation techniques is evaluated by comparing the performance of the techniques developed in this study (LSE), Minimum Mean Square Error (MMSE), and Deep Neural Network (DNN) with those documented in recent literature, especially deep learning-based approaches presented in, [40],[34],[12] and [10] for OFDM and 5GNR systems. Table 4 displays each method's Mean Squared Error (MSE) performance at a Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) of 20 dB.

Table 3. Comparing Channel Estimation Methods Quantitatively in SEFDM-Based m-MIMO Systems. Each estimator's correlation-based channel matching accuracy and MSE are shown in the table. More accurate channel reconstruction is indicated by a lower MSE and a higher correlation coefficient. Over the whole range of channel gains, the DNN-based estimator exhibits improved accuracy and resilience

No | Estimation Technique | Mean Square Error (MSE) | Channel Matching Accuracy |

1 | Least Square Error (LSE) | 1.2776 | Low – correlation coefficient < 0.85; high deviation observed. |

2 | Minimum Mean Square Error (MMSE) | 1.055 | Moderate – correlation between 0.85–0.95; improved fit in mid/high gain. |

2 | Deep Neural Network (DNN) | 0.498 | High – correlation > 0.95; strong alignment over full gain range. |

Figure 8. The graphic highlights the DNN estimator's resilience and learning capacity in spectrally compressed SEFDM m-MIMO environments by showing how it consistently produces lower MSE than conventional techniques, especially when SNR is low

Table 4. Channel Estimation Methods' MSE Comparison at SNR = 20 dB

No | References | MSE (lower is best) | Method |

1 | This work | 1.2776 | LSE |

2 | This work | 1.055 | MMSE |

3 | This work | 0.498 | DNN |

4 | [40] | 0.703 | DNN [He et al., 2018] |

5 | [34] | 0.676 | DNN-based [Ye et al., 2018] |

6 | [12] | 0.46 | AE-DENet [Fola et al.,2024] |

7 | [10] | 0.47 | FSRCNN-based [Sunita et al.,2024] |

The suggested DNN model performs better than both traditional methods and previously published deep learning-based estimators, as Table 3. illustrates. In particular, the suggested DNN exhibits better generalization and estimation accuracy, with a 29% lower MSE than He et al.[40] and around a 26% improvement over Ye et al.[34]. This improvement may be ascribed to the neural network's meticulous architectural design, the use of efficient optimization methods like Adam, and the integration of realistic and varied training data that captures a range of fading situations.

With an MSE of 0.498, our suggested DNN model outperforms more contemporary models like AE-DENet and FSRCNN-based estimators. In particular, the autoencoder-based data enhancement network AE-DENet outperformed the conventional LS and MMSE techniques, achieving an MSE of 0.45 at 20 dB SNR [12]. Similarly, the FSRCNN-based model provided a low-complexity, high-accuracy option for channel estimation, with an MSE of 0.47 [10]. These findings demonstrate how deep learning architectures for channel estimation have advanced. The performance of our DNN model is comparable to these new techniques, highlighting the significance of training data variety and neural network architecture in reaching high estimation accuracy.

- CONCLUSION

In this paper, three channel estimation methods are compared and evaluated in the context of (m-MIMO) systems in 5G NR and beyond: (LSE), (MMSE), and a (DNN)-based approach. The system configuration consists of 32×32 MIMO channels, 256-QAM modulation, and the use of SEFDM to improve spectral efficiency, which is accomplished by compressing subcarrier spacing with a compression factor  , which boosts data throughput at the cost of inter-carrier interference (ICI). Channel conditions are modeled using Nakagami-m fading, and pilot structures are optimized using distributed Demodulation Reference Signals (DMRS), specific reference signals used in 5G NR for precise channel estimation.

, which boosts data throughput at the cost of inter-carrier interference (ICI). Channel conditions are modeled using Nakagami-m fading, and pilot structures are optimized using distributed Demodulation Reference Signals (DMRS), specific reference signals used in 5G NR for precise channel estimation.

LSE and MMSE estimators work well at high SNRs, but their accuracy drastically declines in low-SNR and highly dynamic channel circumstances, according to quantitative tests conducted over a broad range of SNRs. In particular, the MSE of 0.498 obtained by the DNN-based estimator is 52.8% lower than that of the LSE (1.2776) and the MMSE (1.055). Additionally, the DNN estimator achieves a channel matching correlation coefficient that is higher than 0.95, which shows that it is highly aligned with the real channel circumstances.

Without depending on previous statistical information of the channel, the DNN model learns the intricate, nonlinear correlations between incoming signals and channel coefficients, exhibiting strong generalization capabilities. Because of its versatility, it performs well across a range of SNR levels and channel conditions. New Contribution: This paper presents a DNN-based channel estimation framework designed for SEFDM-based m-MIMO systems, demonstrating its effectiveness over conventional LSE and MMSE techniques in demanding communication settings. Future work, the incorporation of attention mechanisms into the DNN architecture may be investigated in future studies to improve computing efficiency and estimation accuracy in real-time applications.

REFERENCES

- M. Ahmad, M. S. Sarwar, and S. Y. Shin, “Deep Learning Assisted Channel Estimation for Adaptive Parameter Selection in mMIMO-SEFDM,” IEEE Internet Things J., pp. 1–1, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2025.3554763.

- C. Dai, S. Xiang, L. Xie, S. Garg, G. Kaddoum, and M. M. Hassan, “An Improved Nonlinear Precoding Scheme in Multicarrier Signaling Optimization for Transportation Networks Applications,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., pp. 1–9, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2025.3531663.

- X. Wang, Y. Zhao, and Z. Huang, “A Survey of Deep Transfer Learning in Automatic Modulation Classification,” IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw., pp. 1–1, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1109/TCCN.2025.3558027.

- Y. Y. U. Ongyi et al., “High spectral efficiency modulation scheme based on joint interaction of orthogonal compressed chirp division multiplexing and power superimposed code,” Optics Express, vol. 32, no. 6, pp.9671-9685, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.514839.

- M. Ahmad, M. Sarwar, S. Shin, “Enhancing mMIMO-SEFDM System through Deep Learning-Based Channel Estimation and Adaptive Parameter Selection,” Authorea Preprints, 2024, https://doi.org/10.36227/techrxiv.172262850.03634715/v1.

- A. Tariq, M. Sajid Sarwar and S. Y. Shin, "Orthogonal Time-Frequency–Space Multiple Access Using Index Modulation and NOMA," in IEEE Wireless Communications Letters, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 1456-1460, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1109/LWC.2025.3544234.

- L. Xiang, K. Xu, J. Hu, C. Masouros and K. Yang, "Robust NOMA-Assisted OTFS-ISAC Network Design With 3-D Motion Prediction Topology," in IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 11, no. 9, pp. 15909-15918, 1 May1, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2024.3352391.

- W. Chen, J. Tao, L. Ma and G. Qiao, "Vector-Approximate-Message-Passing-Based Channel Estimation for MIMO-OFDM Underwater Acoustic Communications," in IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 496-506, April 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/JOE.2023.3337349.

- V. N. Senthil Kumaran, R. Guttula, and G. N. Reddy, “Hybrid Optimized LMMSE-Based Channel Estimation with Low Power Trellis Coded Modulation,” Cybernetics and Systems, pp. 1-23, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1080/01969722.2024.2343989.

- S. Khichar, W. Santipach, L. Wuttisittikulkij, A. Parnianifard, and S. Chaudhary, “Efficient Channel Estimation in OFDM Systems Using a Fast Super-Resolution CNN Model,” J. Sens. Actuator Networks, vol. 13, no. 5, p. 55, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/jsan13050055.

- S. Kanwal and S. Jiriwibhakorn, “Advanced Fault Detection, Classification, and Localization in Transmission Lines: A Comparative Study of ANFIS, Neural Networks, and Hybrid Methods,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 49017–49033, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3384761.

- E. Fola, Y. Luo, and C. Luo, “AE-DENet: Enhancement for Deep Learning-based Channel Estimation in OFDM Systems,” in GLOBECOM 2024 - 2024 IEEE Global Communications Conference, IEEE, pp. 1449–1454, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/GLOBECOM52923.2024.10901113.

- R. Martínez, F. E. López Giraldo, J. M. Luna Rivera, J. D. Navarro Restrepo, and J. D. Rojas Usuga, “Evaluation of Solar Panel Bandwidth for RGB Channels in Visible Light Communication,” IEEE Lat. Am. Trans., vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 240–248, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/TLA.2024.10431426.

- H. Alraie, R. Alahmad, and K. Ishii, “Double the data rate in underwater acoustic communication using OFDM based on subcarrier power modulation,” J. Mar. Sci. Technol., vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 457–470, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00773-024-00989-2.

- N. Almaymoni, O. Alkhazragi, W. H. Gunawan, G. Melinte, T. K. Ng, and B. S. Ooi, “High-Speed 645-nm VCSELs for Low-Scattering-Loss Gb/s Underwater Wireless Optical Communications,” IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett., vol. 36, no. 6, pp. 377–380, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/LPT.2024.3360229.

- Y. Qi, T. Zhang, Y. Feng, Z. Qin and D. He, "Design and Implementation of Spectrally Efficient Frequency Division Multiplexing Receiver," in IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 121482-121491, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3328234.

- Y. Hama and H. Ochiai, "On the Achievable Spectral Efficiency of Non-Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing," in IEEE Transactions on Communications, vol. 71, no. 11, pp. 6246-6257, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/TCOMM.2023.3300328.

- X. Liu. Spectrally and Energy Efficient Wireless Communications: Signal and System Design, Mathematical Modelling and Optimisation (Doctoral dissertation, UCL (University College London)). 2023. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10176195.

- R. Mani, A. Rios-Navarro, J.-L. Sevillano-Ramos, and N. Liouane, “Improved 3D localization algorithm for large scale wireless sensor networks,” Wirel. Networks, vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 5503-5518, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11276-023-03265-0.

- E. H. Kadhim and A. T. Abdulsadda, “Improving the Size of the Propellers of the Parrot Mini-Drone and an Impact Study on its Flight Controller System,” Int. J. Robot. Control Syst., vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 171–186, 2023, https://doi.org/10.31763/ijrcs.v3i2.933.

- J. Shi et al., “Neural Network Equalizer in Visible Light Communication: State of the Art and Future Trends,” Front. Commun. Networks, vol. 3, no. April, pp. 1–11, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/frcmn.2022.824593.

- X. Hou et al., “Non-Orthogonal Physical Layer (NOPHY) Design towards 5G Evolution and 6G,” IEICE Trans. Commun., vol. E105B, no. 11, pp. 1444–1457, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1587/transcom.2021EBP3192.

- X. Liang, H. Niu, and B. Cai, “Blind CFO Estimator for Spectrally Efficient Frequency Division Multiplexing System,” IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett., vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 59–62, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/LPT.2021.3137329.

- X. Liang, H. Niu, A. Liu, Z. Gao, and Y. Zhang, “Joint STO and DFO Estimation for SEFDM in Low-Earth-Orbit Satellite Communications,” IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst., vol. 58, no. 4, pp. 3725–3729, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/TAES.2021.3140186.

- H. J. Park, S. -M. Kang, I. Ha and S. -K. Han, "Hexagonal QAM-Based Four-Dimensional AMO-OFDM for Spectrally Efficient Optical Access Network Transmission," in IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 176814-176819, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2957844.

- X. Liang, A. Liu, B. Cai, S. Peng, and C. Han, “Low-Complexity CFO Estimator for Spectrally Efficient Frequency Division Multiplexing System,” IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., vol. 71, no. 6, pp. 6762–6766, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2022.3161668.

- S. Stainton, M. Johnston, S. Dlay, and P. A. Haigh, “Evm loss: A loss function for training neural networks in communication systems,” Sensors (Switzerland), vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 1–9, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/s21041094.

- N. H. Nguyen, H. H. Nguyen and B. Berscheid, "SVD-Based Design for Non-Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing," in IEEE Communications Letters, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 1343-1347, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/LCOMM.2020.3045719.

- E. H. Kadhim and A. T. Abdulsadda, “The flight management system in parrot mini-drone,” AIP Conf. Proc., vol. 2776, no. 1, p. 40008, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0137270.

- E. Zimaglia, D. G. Riviello, R. Garello, and R. Fantini, “A Deep Learning-based Approach to 5G-New Radio Channel Estimation,” in 2021 Joint European Conference on Networks and Communications & 6G Summit (EuCNC/6G Summit), IEEE, pp. 78–83, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/EuCNC/6GSummit51104.2021.9482426.

- H. Ghannam, D. Nopchinda, M. Gavell, H. Zirath and I. Darwazeh, "Experimental Demonstration of Spectrally Efficient Frequency Division Multiplexing Transmissions at E-Band," in IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques, vol. 67, no. 5, pp. 1911-1923, May 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/TMTT.2019.2901667.

- S. Osaki, M. Nakao, T. Ishihara, and S. Sugiura, “Differentially Modulated Spectrally Efficient Frequency-Division Multiplexing,” IEEE Signal Process. Lett., vol. 26, no. 7, pp. 1046–1050, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/LSP.2019.2918688.

- D. Vasilyev and A. Rashich, "SEFDM-signals Euclidean Distance Analysis," 2018 IEEE International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Photonics (EExPolytech), pp. 75-78, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1109/EExPolytech.2018.8564439.

- H. Ye, G. Y. Li and B. -H. Juang, "Power of Deep Learning for Channel Estimation and Signal Detection in OFDM Systems," in IEEE Wireless Communications Letters, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 114-117, Feb. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1109/LWC.2017.2757490.

- M. Jia, Z. Yin, Q. Guo, G. Liu and X. Gu, "Waveform Design of Zero Head DFT Spread Spectral Efficient Frequency Division Multiplexing," in IEEE Access, vol. 5, pp. 16944-16952, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2740267.

- T. Xu and I. Darwazeh, “A Joint Waveform and Precoding Design for Non-Orthogonal Multicarrier Signals,” in 2017 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC), IEEE, pp. 1–6, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1109/WCNC.2017.7925796.

- J. Huang, Q. Sui, Z. Li and F. Ji, "Experimental Demonstration of 16-QAM DD-SEFDM With Cascaded BPSK Iterative Detection," in IEEE Photonics Journal, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 1-9, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1109/JPHOT.2016.2552480.

- N. Wu, Y. Ma, and R. Jiang, “Message Passing Receiver for SEFDM Signaling Over Multipath Channels,” in Advanced Receiver Design for Multicarrier FTN Signaling in 6G Systems, pp. 29–42, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-96-0730-3_2.

- N. Wu, Y. Ma, and R. Jiang, “Joint Channel Estimation and Equalization for Index-Modulated SEFDM Signaling,” in Advanced Receiver Design for Multicarrier FTN Signaling in 6G Systems, pp. 43–72, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-96-0730-3_3.

- C.-K. Wen, W.-T. Shih, and S. Jin, “Deep Learning for Massive MIMO CSI Feedback,” IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett., vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 748–751, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1109/LWC.2018.2818160.

Enhancement of Channel Estimation in Spectrally Efficient Frequency Division Multiplexing-based Massive MIMO Systems for 5G NR and Beyond: A Comparative Analysis of LSE, MMSE, and Deep Neural Network Architectures (Esraa H.Kadhim)