Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro ISSN: 2685-9572

An Analysis of UAV Security and Privacy Concerns of Communication Systems

Farah Alaa A. Hassan, Hiba Rashid Almamoori, Nuha Kareem Hameed Al-Msarhed

Department of cyber security, College of information technology, University of Babylon, Babylon, Iraq

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 20 March 2025 Revised 27 April 2025 Accepted 07 May 2025 |

|

Wireless communication is one of the fastest-growing research fields, with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) increasingly deployed as mobile router points in high-traffic areas such as bus stations, metro stations, and airport terminals to address connectivity challenges. However, despite their utility, UAVs face significant security and privacy risks. This paper presents a comprehensive analysis of these vulnerabilities through a systematic four-level classification: sensor, communication, software, and hardware. For each level, we examine (1) common weaknesses exploitable by malicious actors, (2) potential threats to civilian UAV applications, (3) active and passive attacks compromising security and privacy, and (4) possible countermeasures to mitigate such risks. Additionally, we summarize key findings on UAV security and privacy issues and highlight critical unresolved challenges. Finally, we propose future research directions, including the use of fuzzy logic to optimize drone routing by dynamically relocating UAVs to low-activity zones based on fuzzy rule-based decisions. |

Keywords: UAVs; Security; Fuzzy-logic Rules; Communication System |

Corresponding Author: Farah Alaa A. Hassan, University of Babylon, College of information technology, Department of cyber security, Babylon, Iraq Email: coj.abdulsad@atu.edu.iq |

This work is open access under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: F. A. A. Hassan, H. R. Almamoori, and N. K. H. Al-Msarhed “An Analysis of UAV Security and Privacy Concerns of Communication Systems,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 138-146, 2025, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v7i2.13057. |

- INTRODUCTION

Effective port management is essential for ensuring efficient cargo handling, yet inspection and maintenance remain challenging due to the complex environments of port facilities. To address this, drones (UAVs) are increasingly deployed for active monitoring and infrastructure maintenance, significantly enhancing operational efficiency. UAVs excel in surveilling port perimeters, rapidly detecting unauthorized access or suspicious activities, enabling security personnel to respond swiftly and prevent potential threats. Their compact size, low operational costs, and minimal risk make them a versatile solution for diverse applications, including smart agriculture, surveillance, logistics, and disaster response [1]-[2].

A major trend in Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) development is the emergence of multi-role fleet integration, where diverse drones operate as a unified, AI-driven network [3]. These intelligent swarm systems utilize real-time big data analytics, machine learning-based autonomy, and adaptive control algorithms to dynamically optimize mission performance [4]. By enabling seamless coordination, decentralized decision-making, and self-improving operational efficiency, such networks enhance capabilities in surveillance, logistics, and disaster response—all while reducing human intervention [5]. This shift toward collaborative autonomy not only increases mission success rates but also paves the way for next-generation applications in smart cities and defense (see Figure 1). The rapid evolution of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) technology is revolutionizing port security and industrial operations, providing scalable, cost-efficient solutions to modern infrastructure challenges. Equipped with advanced sensors, real-time monitoring capabilities, and AI-powered analytics, UAVs enhance situational awareness, automate inspections, and streamline logistics in complex environments [6]-[10]. From perimeter surveillance and cargo tracking to hazard detection and emergency response, drone systems minimize risks, reduce operational downtime, and lower labor costs—making them indispensable for smart ports and Industry 4.0 applications. As regulatory frameworks adapt, UAVs are poised to become a cornerstone of next-generation security and automation in critical infrastructure worldwide [11].

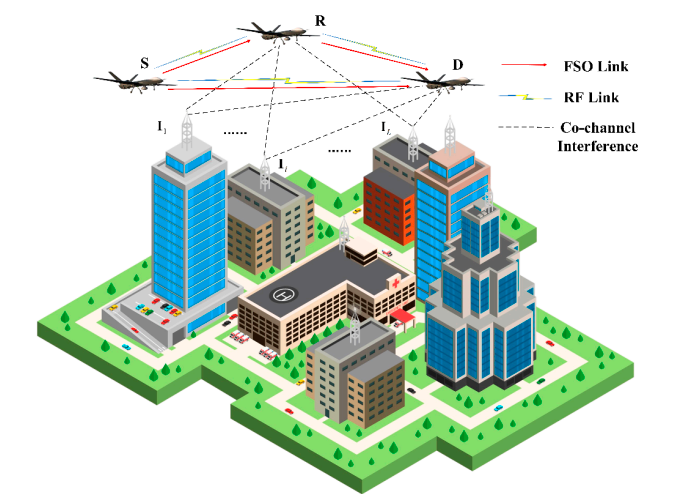

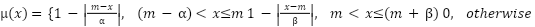

Figure.1 RF\PSO drone communication urban communication system, [12]

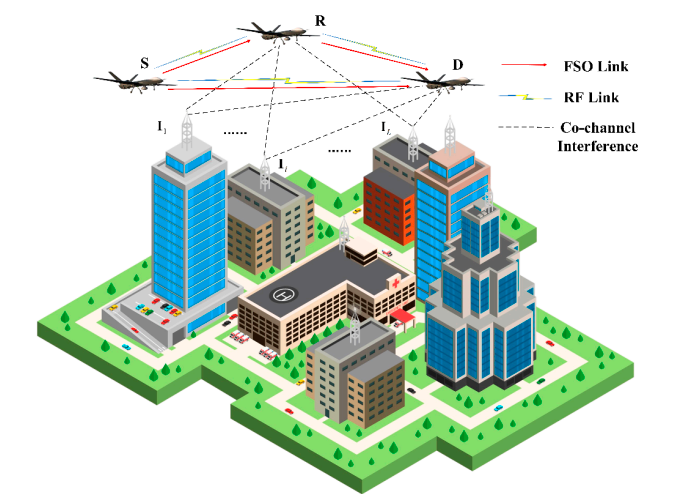

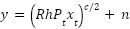

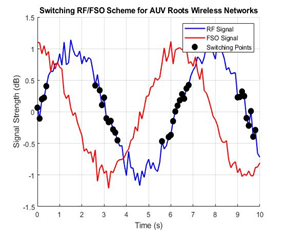

Figure 1 shows hot spot region with many hot spots wireless communication users. Many buildings and may be factory needs more accessing to the internet. Most of these building and facilities required the internet for especial time interval. Deployment the UAV as substation for wireless communication as one common recent solution for the crowded area accessing networks. Essentially the protocol for types of these channel can be considered as [13]-[19]: The cooperative form of two communication means can currently be classified into two categories: hybrid RF/FSO communication systems and mixed RF/FSO communication systems [20]–[26]. A combined RF/FSO communication system, which often uses FSO to address the last-mile access issue between users and core networks, is an effective method of increasing communication coverage. [27]–[32] offers a comprehensive performance analysis of the combined RF/FSO communication system under interference. The performance of a mixed RF/FSO communication system with amplify-and-forward (AF) relaying, in which co-channel interference (CCI) influences the received RF signals, is investigated in [33][34]. Assuming that the impact of CCI is considered at both the relay and the destination, closed-form formulas for the system's bit error probability (BEP) and outage probability (OP) are given in [35]. Figure 2 shows the process by which UAVs transition between MMW RF and FSO communications. Regarding the RF/FSO cooperative communication network, when the instantaneous SINR at D surpasses the threshold  , UAVs send data across MMW RF links. A single-bit feedback signal is used to trigger the FSO transmission in the event that the instantaneous SINR degrades. The system will start utilizing the RF links to keep in touch as soon as they are open for use. Stated differently, there is only one active means at a time. Furthermore, an outage occurs in the cooperative communication network if the instantaneous SNR of the FSO links at D falls below the threshold

, UAVs send data across MMW RF links. A single-bit feedback signal is used to trigger the FSO transmission in the event that the instantaneous SINR degrades. The system will start utilizing the RF links to keep in touch as soon as they are open for use. Stated differently, there is only one active means at a time. Furthermore, an outage occurs in the cooperative communication network if the instantaneous SNR of the FSO links at D falls below the threshold  .Performance of AUVs.

.Performance of AUVs.

Obviously from Figure 2 the switching between the RF and FSO is done based upon the equipment the AUVs has at the location that its deployment for. And another thing sometime there are another channel share for the networking that is used for. AUVs are now a crucial component of naval and military operations. They are employed for intelligence collection, reconnaissance, and surveillance. Armed forces can utilize military drones, including unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), which provide real-time aerial photographs, video footage, and sensor data, to identify targets, monitor enemy activity, and assess combat conditions. Furthermore, they can be outfitted with weaponry for offensive actions. A key component of military tactics is surveillance, and drones are excellent at it [37]-[41].

Figure 2. Switching RF\FSO scheme for AUV roots wireless networks, [36]

The sensors mounted on drones are airborne mobile sensors used in military surveillance. They collaborate between stationary ground sensors and mobile sensors in the air to efficiently increase the drones' detecting area [42]-[44]. Drones are essential for intelligence gathering in addition to surveillance and reconnaissance. In the past, military intelligence collection has relied on human-controlled aerial vehicles; but, as more autonomous systems become available, it is becoming more and more crucial to exploit drones' situational awareness skills for information collection [45]-[46]. This information is crucial for comprehending opposing strategies, spotting weaknesses, and creating potent defenses.

In order to provide safe point-to-point communication between the drone and any wireless channel (RF link) or free space optics channel (FSO), The goal of the project is to include a fuzzy-logic controller that enables eavesdroppers to use either software or hardware to detect information. Modifying the channeling communication frequently and zone make the security side more efficient and reliable. The rest of the paper is organized as: section two presents the mathematical modelling for the method, section three presents the setup and methodology and last but not least section four has the simulation results, finally the conclusion and discussion presents in section five.

- METHODS

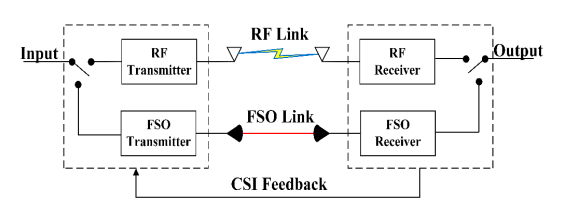

Dependability is crucial for every communication strategy. There should be little chance of error and the data should get at its destination efficiently. For both terrestrial and space communication, FSO systems provide a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which can result in a high transmission rate. As was previously mentioned, a number of problems, such as scattering, absorption, transceiver misalignment, and turbulence-induced fading, restrict the performance of these systems. The destination's signal can be written as:

|

| (1) |

Where  is the average source transmit power, n is the AWGN with zero mean and variance,

is the average source transmit power, n is the AWGN with zero mean and variance,  , which is independent of the signal,

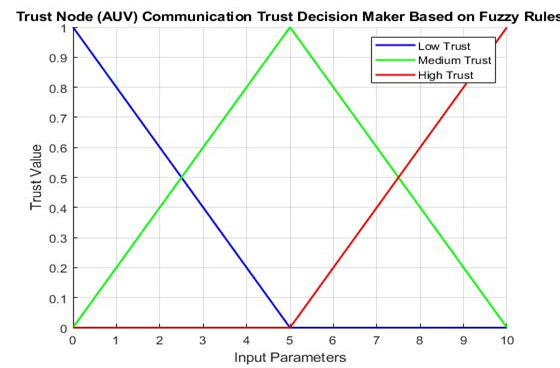

, which is independent of the signal,  is the overall channel impulse response, xt is the transmitted symbol ∈{0,1}, and c is the parameter, which has a value of 1 for heterodyne detection (HD) and 2 for intensity modulation/direct detection (IM/DD). Ad hoc UAV networks, also known as FANETs, function in this manner. These networks have a dynamic topology and provide significant dangers. A prior study found that drone-assisted public safety networks present broad security threats [47]–[49]. It demonstrates how the complexity of UAV networks increases their susceptibility to attacks. Communication modules and sensor inputs are the primary targets of these attacks. Potential DoS attacks could result from UAV communication risks such intercepting or cutting off the Flight Controller-GCS communication link. Furthermore, it is necessary to develop cryptographic algorithms for FANETs that take into account their special features, which include latency and processing capacity for data routing [26]. Figure 3 shows that in order to interfere with the whole UAV network, the adversary must either compromise the GCS or four backbone UAVs. Developing increasingly sophisticated UAV network topologies for mixed UAVs.

is the overall channel impulse response, xt is the transmitted symbol ∈{0,1}, and c is the parameter, which has a value of 1 for heterodyne detection (HD) and 2 for intensity modulation/direct detection (IM/DD). Ad hoc UAV networks, also known as FANETs, function in this manner. These networks have a dynamic topology and provide significant dangers. A prior study found that drone-assisted public safety networks present broad security threats [47]–[49]. It demonstrates how the complexity of UAV networks increases their susceptibility to attacks. Communication modules and sensor inputs are the primary targets of these attacks. Potential DoS attacks could result from UAV communication risks such intercepting or cutting off the Flight Controller-GCS communication link. Furthermore, it is necessary to develop cryptographic algorithms for FANETs that take into account their special features, which include latency and processing capacity for data routing [26]. Figure 3 shows that in order to interfere with the whole UAV network, the adversary must either compromise the GCS or four backbone UAVs. Developing increasingly sophisticated UAV network topologies for mixed UAVs.

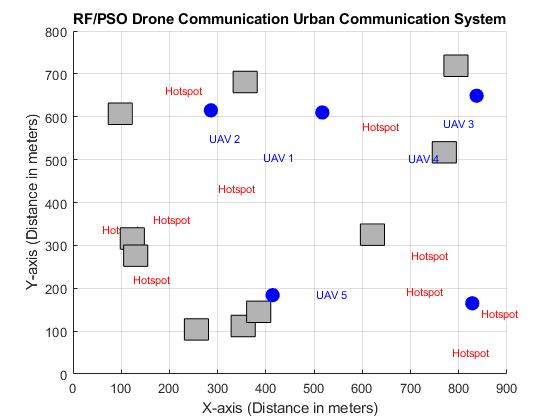

By using the fuzzy set membership function can be determining which zone can be working without any attacker. The following is the definition of the triangular fuzzy numbers' membership function:

|

| (2) |

A triplet (m, a, b) LR represents a triangular fuzzy number  , where m is the fuzzy number's mean value and α and β are its left and right boundary values, respectively. Table 1 listed the 5 by 5 fuzzy rule where each categorize represented the set of UAV that is derived from membership function shown in Figure 4. From Figure 2 each UAV that is cover range with specific area, and would be given especial fuzzy rules based up on how far from the users its self. Once there is attacker that make a new load blacked at the area and at that time switching from these area zone to another based up on the fuzzy rules membership function that is listed in Table1.

, where m is the fuzzy number's mean value and α and β are its left and right boundary values, respectively. Table 1 listed the 5 by 5 fuzzy rule where each categorize represented the set of UAV that is derived from membership function shown in Figure 4. From Figure 2 each UAV that is cover range with specific area, and would be given especial fuzzy rules based up on how far from the users its self. Once there is attacker that make a new load blacked at the area and at that time switching from these area zone to another based up on the fuzzy rules membership function that is listed in Table1.

Figure 3. Schematic diagram for the proposed fuzzy drone communication system, [38]

Figure 4. Trust nodes interval fuzzy member function

Table 1. Lists the fuzzy logic rules.

AUV set 1 | N | Z | P |

AUV set II |

N | N | Z | Z |

Z | Z | Z | P |

P | P | Z | P |

- Simulation Setup

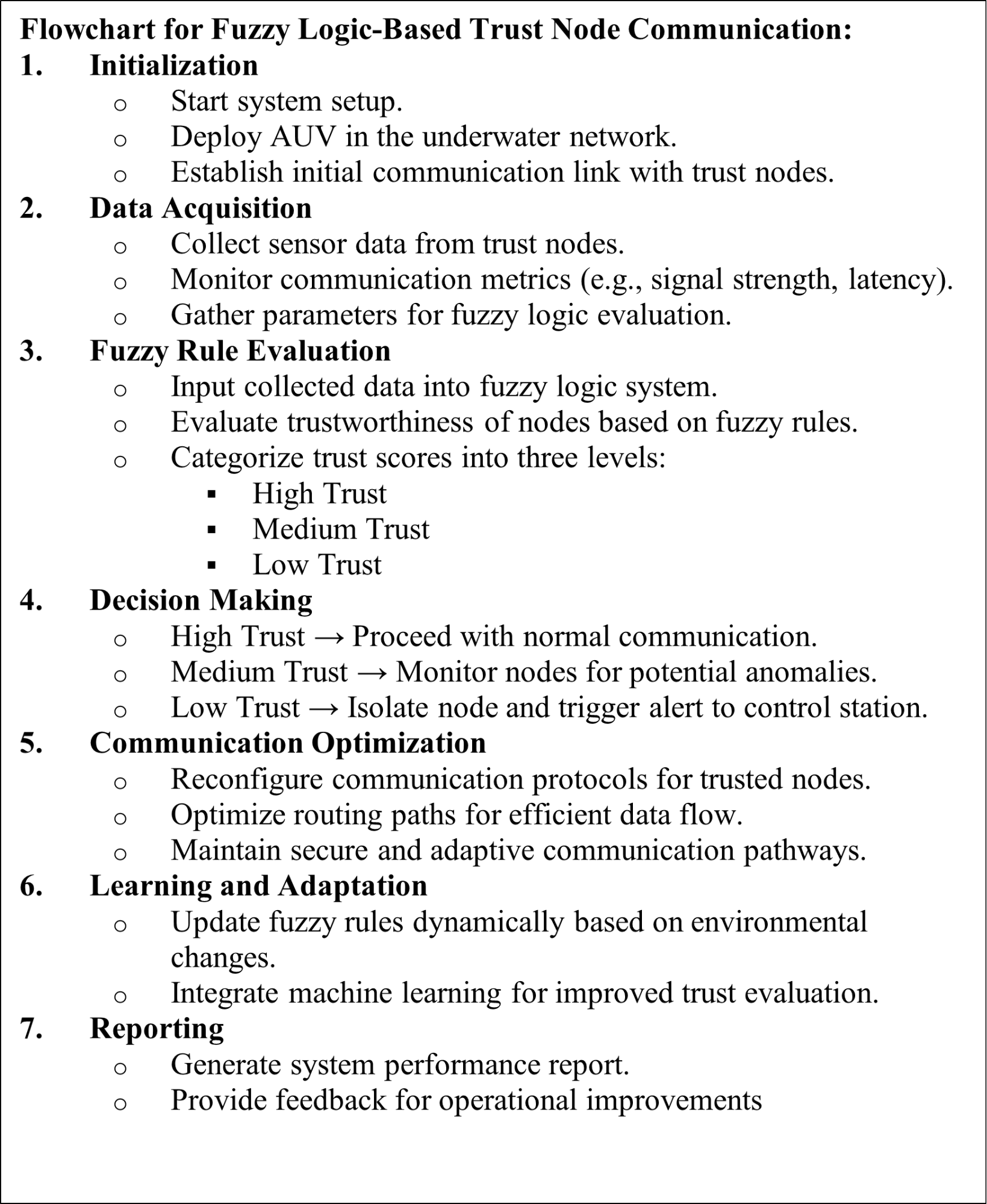

Each drone uses a fuzzy logic method to determine its neighbor's trust score after gathering the required data. The received signal strength indication, packet delivery ratio, transmission delay, energy, and humidity are only a few of the input characteristics that the suggested system takes into account. To improve performance, triangular and trapezoidal membership [50], functions of the input parameters are used. After then, fuzzy rules are used in the inference engine step to produce a final numerical result. This last number indicates the neighboring node's direct trust evaluation. Figure 5 shows the setup of the suggested fuzzy logic-based trust management paradigm.

The simulation algorithm of Trust AUV nodes is depicted in Figure 6, where triangular linguistic variable membership function used as in Figure 3. This phase requires that every rule in the suggested fuzzy logic model be defined, followed by an explanation of the rules that represent actual circumstances: The worst-case situation is depicted in the first rule. The best scenario, however, is represented by the second rule. According to the third rule, the system must see the node as reliable because of its low battery, which suggests that inadvertent misconduct is taken into account. According to rules four through seven, if every variable has a negative value, with the exception of one that has a positive value. The node is then seen as having a poor trust value and is hence unreliable. Because the node has a poor RSSI because of the high humidity, Rule 8 mandates that the system regard it as trustworthy. This suggests that the system considers unfavorable.

|

|

Figure 5. Trust Node (AUV) communication trust decision maker based upon fuzzy rules

- RESULT AND DISCUSSION

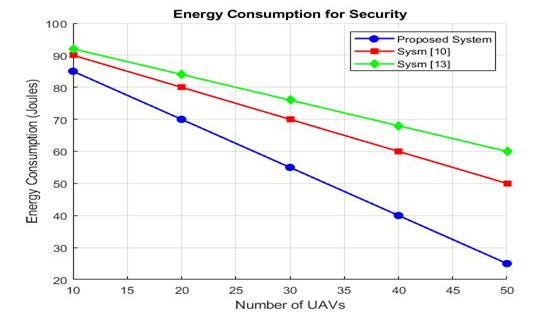

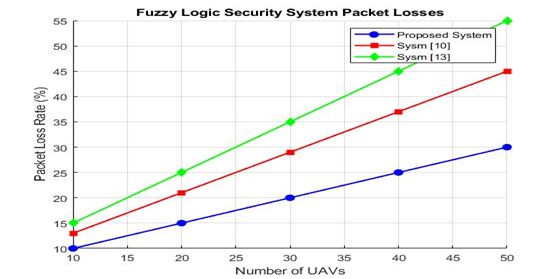

The performance of the suggested plan has been calculated by comparing it to the current schemes [10],[13]. The effectiveness of the suggested method in dynamically differentiating between purposeful and inadvertent hostile UAVs within the Fuzzy AUV networks (FANET) has been assessed using the network simulator MATLAB. Performance metrics like energy use, service quality, and experience quality are measured in contrast. Table 2 also describes the simulation scenario, which makes use of the suggested scheme to explain a number of data, such as the variation in drone speed, energy, and packet delivery ratios when compared to inadvertently non-cooperative drones.

Compared to processing and operation combined, communication in proposed system consumes significantly more battery power per node. In addition to communication, UAVs need a large amount of battery capacity for functions like flying and autonomy in the atmosphere. On the other hand, performance metrics are measured, such as energy usage, service quality, and experience quality. Numerous findings are explained by the suggested trust model in the simulation environment, such as the examination of drone speed and packet drop ratios in comparison to non-cooperative drones and the correlation between UAV count and energy usage. Figure 7 shows that, in comparison to the current schemes, such as sys [10] (using tree multi hops classifier methods) and sys [13] (wireless trust based one minimum distance method), less energy has been used as the number of drones has increased.

Obviously from Figure 7 can be seen that: Any network with more UAV usually has worse speeds as the number of drones rises. The efficient strategy is irrelevant at that point since it typically gets less effective as the number of UAVs in the network steadily increases. This results in an inherent latency in the network. The suggested approach aims to progressively increase the number of UAVs in order to gain a better understanding of the behavioral patterns of the different protocol schemes. Because routes are only created when required, this network takes a long time to update the routing matrix. This flying ad-hoc protocol's dynamic changes are excellent, but keep in mind that they increase processing demands. This pre-planner routing makes it possible for the packet to be delivered to its destination successfully.

The leader drone chooses which UAV to transmit the info to next by instantly communicating with its adjacent leaders rather than verifying each drone. In proposed system, the entire routing process is controlled by the leaders of the many clusters that are situated along the path. Therefore, the suggested method can outperform sys [10] and sys [13] in terms of throughput. Figure 7 illustrates that the suggested system is not significantly impacted by an increase in nodes. Compared to the previously mentioned existing techniques, the suggested scheme has a little higher delay. Because of a higher node density, the proposed method also provides decreased overhead, as seen in Figure 8. Figure 8 shows that the packet loss increased as number of AUV increased almost linearly with the three methods. The proposed system has the lower losses rate if we compared it with the others.

Figure 6. Fuzzy trust nodes AUV communication algorithm,membership function for trust nodes

Table 2. Setup parameters

Parameters | Range of values |

The simulation area's size | N (950×750×850) m3 |

The packet or message's size | 3500 bits |

The quantity of drones | 35 |

The positioning of the drone | Random |

Mobility model | Random Waypoint |

Traffic | CBR |

Velocity of drone (range) | 45–65 m per sec. |

Figure 7. Energy consumption for security

Figure 8. Fuzzy logic security system packet losses

- CONCLUSIONS

Three methods were used (two from literature and one proposed system) to extensively examine UAV security issues, and communication. We also talked about the risks, potential remedies, and privacy concerns associated with UAVs. We then discussed the lessons we had learnt about the privacy and security implications of UAVs and offered potential avenues for further research. As the number of commercial UAVs flying in civilian airspace increased, security and privacy concerns emerged as a significant national security priority. Therefore, it is imperative that industry, academia, and law enforcement collaborate to develop new security frameworks, standards, and legislation. Security and privacy concerns are lagging far behind as current drone manufacturers introduce the next generation of commercial UAVs to the market. Our survey offers the scientific community a useful resource for information.

One useful technique for identifying insider threats is trust management. Creating a conceptual and analytical trust model for Fuzzy UAV that can assess and comprehend node behavior is the primary issue in this field. This paper introduces drone security communication, a fuzzy-based UAV behavior analytics for trust management that uses both direct and indirect data. In contrast to earlier models, the suggested model improves the network's reliability in inclement weather and with weak signal strength (RSSI). Moreover, Fuzzy UAV communication system can successfully differentiate between benign and malevolent UAV activities.

REFERENCES

- S. Hayat, E. Yanmaz and R. Muzaffar, "Survey on Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Networks for Civil Applications: A Communications Viewpoint," in IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 2624-2661, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2016.2560343.

- L. Gupta, R. Jain and G. Vaszkun, "Survey of Important Issues in UAV Communication Networks," in IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 1123-1152, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2015.2495297.

- N. Hossein Motlagh, T. Taleb and O. Arouk, "Low-Altitude Unmanned Aerial Vehicles-Based Internet of Things Services: Comprehensive Survey and Future Perspectives," in IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 899-922, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2016.2612119.

- R. Kellermann, T. Biehle, and L. Fischer, “Drones for parcel and passenger transportation: A literature review,” Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, vol. 4, p. 100088, 3 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2019.100088.

- L. Kapustina, N. Izakova, E. Makovkina, E., & Khmelkov, M. (2021). The global drone market: main development trends. In SHS web of conferences, vol. 129, p. 11004, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/202112911004.

- R. Rodriguez, “Perspective: Agricultural aerial application with unmanned aircraft systems: Current regulatory framework and analysis of operators in the United States,” Transactions of the ASABE, vol. 64, no. 5, pp. 1475-1481, 2021, https://doi.org/10.13031/trans.14331.

- Z. Liu, Z. Li, B. Liu, X. Fu, I. Raptis, and K. Ren, “Rise of MiniDrones,” in Proceedings of the 2015 Workshop on Privacy-Aware Mobile Computing, pp. 7–12, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1145/2757302.2757303.

- [S. Park, H. T. Kim, S. Lee, H. Joo and H. Kim, "Survey on Anti-Drone Systems: Components, Designs, and Challenges," in IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 42635-42659, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3065926.

- H. Sedjelmaci, S. M. Senouci and M. -A. Messous, "How to Detect Cyber-Attacks in Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Network?," 2016 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), pp. 1-6, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1109/GLOCOM.2016.7841878.

- E. Barka, C. A. Kerrache, N. Lagraa, A. Lakas, C. T. Calafate, J. C. Cano, UNION: a trust model distinguishing intentional and UNIntentional misbehavior in inter‐UAV communication. Journal of advanced transportation, vol. 2018, no. 1, p. 7475357, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7475357.

- R. Ganesan, X. M. Raajini, A. Nayyar, P. Sanjeevi kumar, E. Hossain, and A. H. Ertas, “Bold: Bio-inspired optimized leader election for multiple drones,” Sensors, vol. 20, no. 11, p. 3134, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/s20113134.

- X. Du, Y. Li, S. Zhou, and Y. Zhou, “ATS-LIA: A lightweight mutual authentication based on adaptive trust strategy in flying ad-hoc networks, peer-to-peer Netw,” Appl., vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 1979–1993, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12083-022-01330-7.

- V. Bhardwaj, N. Kaur, S. Vashisht, and S. Jain, “SecRIP: secure and reliable intercluster routing protocol for efficient data transmission in flying ad hoc networksTrans,” Emerg. Telecommun. Technol., vol. 32, no. 6, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1002/ett.4068.

- C. F. E. de Melo et al., "UAVouch: A Secure Identity and Location Validation Scheme for UAV-Networks," in IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 82930-82946, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3087084.

- Y. Wang et al., "CATrust: Context-Aware Trust Management for Service-Oriented Ad Hoc Networks," in IEEE Transactions on Services Computing, vol. 11, no. 6, pp. 908-921, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1109/TSC.2016.2587259.

- M. Hosseinzadeh, et al., “An energy-aware routing scheme based on a virtual relay tunnel in flying ad hoc networks,” Alexandria Engineering Journal, vol. 91, pp. 249-260, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2024.02.006.

- S. Yu, J. Lee, A. K. Sutrala, A. K. Das, and Y. Park, “LAKA-UAV: lightweight authentication and key agreement scheme for cloud-assisted unmanned aerial vehicle using blockchain in flying ad-hoc networks,” Comput. Netw., vol. 224, p. 109612, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comnet.2023.109612.

- A. M. Rahmani, S. Ali, E. Yousefpoor, M. S. Yousefpoor, D. Javaheri, P. Lalbakhsh, and S. W. Lee, “OLSR+: a new routing method based on fuzzy logic in flying ad-hoc networks (FANETs),” Veh. Commun., vol. 36, p. 100489, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vehcom.2022.100489.

- W. Zhai, L. Liu, Y. Ding, S. Sun and Y. Gu, "ETD: An Efficient Time Delay Attack Detection Framework for UAV Networks," in IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, vol. 18, pp. 2913-2928, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/TIFS.2023.3272862.

- M. Namdev, S. Goyal, and R. Agarwal, “An optimized communication scheme for energy efficient and secure flying ad-hoc network (FANET),” Wirel. Pers. Commun., vol. 120, no. 2, pp. 1291–1312, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11277-021-08515-y.

- J. Lansky, S. Ali, A. M. Rahmani, M. S. Yousefpoor, E. Yousefpoor, F. Khan, and M. Hosseinzadeh, “Reinforcement learning-based routing protocols in flying ad hoc networks (FANET): a review,” Mathematics, vol. 10, no. 16, p. 3017, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/math10163017.

- Y. Lu, W. Wen, K. K. Igorevich, P. Ren, H. Zhang, Y. Duan, and P. Zhang, “UAV Ad Hoc network routing algorithms in space–air–ground integrated networks: challenges and directions,” Drones, vol. 7, no. 7, p. 448, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/drones7070448.

- A. Lapidoth, S. M. Moser and M. A. Wigger, "On the Capacity of Free-Space Optical Intensity Channels," in IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, vol. 55, no. 10, pp. 4449-4461, 2009, https://doi.org/10.1109/TIT.2009.2027522.

- Xiaoming Zhu and J. M. Kahn, "Free-space optical communication through atmospheric turbulence channels," in IEEE Transactions on Communications, vol. 50, no. 8, pp. 1293-1300, 2002, https://doi.org/10.1109/TCOMM.2002.800829.

- Z.-L. Dan, X.-W. Wu, S.-X. Zhu, T.-X. Zhuang, and J.-Y. Wang, “On the outage performance of dual-hop UAV relaying with multiple sources, in: 2019 Cross Strait Quad-Regional Radio Science and Wireless Technology Conference,” CSQRWC, pp. 1–3, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/CSQRWC.2019.8799304.

- L. C. Andrews and R. L. Phillips, “Laser beam propagation through random media,” Laser Beam Propagation Through Random Media: Second Edition, 2005, https://doi.org/10.1117/3.626196.

- L. C. Andrews, R. L. Phillips, C. Y. Hopen, and M. A. Al-Habash, “Theory of optical scintillation,” J. Opt. Soc. Amer. A, vol. 16, no. 6, pp. 1417–1429, 1999, https://doi.org/10.1364/JOSAA.16.001417.

- H. Wang, H. Zhao, J. Zhang, D. Ma, J. Li and J. Wei, "Survey on Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Networks: A Cyber Physical System Perspective," in IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 1027-1070, Secondquarter, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2019.2962207.

- A. I. Hentati and L. C. Fourati, “Comprehensive survey of UAVs communication networks,” Computer Standards and Interfaces, vol. 72, no. September 2019, p. 103451, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csi.2020.103451.

- Y. Zhi, Z. Fu, X. Sun, and J. Yu, “Security and Privacy Issues of UAV: A Survey,” Mobile Networks and Applications, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 95–101, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11036-018-1193-x.

- A. Sharma, P. Vanjani, N. Paliwal, C. M. Basnayaka, D. N. K. Jayakody, H. C. Wang, and P. Muthuchidambaranathan, “Communication and networking technologies for UAVs: A survey,” Journal of Network and Computer Applications, vol. 168, no. June, p. 102739, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnca.2020.102739.

- F. Noor, M. A. Khan, A. Al-Zahrani, I. Ullah, and K. A. Al-Dhlan, “A review on communications perspective of flying AD-HOC networks: Key enabling wireless technologies, applications, challenges and open research topics,” Drones, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 1–14, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/drones4040065.

- D. Mishra and E. Natalizio, “A survey on cellular-connected UAVs: Design challenges, enabling 5G/B5G innovations, and experimental advancements,” Computer Networks, vol. 182, no. August, p. 107451, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comnet.2020.107451.

- F. Syed, S. K. Gupta, S. Hamood Alsamhi, M. Rashid, and X. Liu, “A survey on recent optimal techniques for securing unmanned aerial vehicles applications,” Transactions on Emerging Telecommunications Technologies, vol. 32, no. 7, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1002/ett.4133.

- M. Yahuza, M. Y. I. Idris, I. B. Ahmedy, A. W. A. Wahab, T. Nandy, N. M. Noor, and A. Bala, “Internet of Drones Security and Privacy Issues: Taxonomy and Open Challenges,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 57 243–57 270, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3072030.

- B. Nassi, R. Bitton, R. Masuoka, A. Shabtai, and Y. Elovici, “SoK: Security and Privacy in the Age of Commercial Drones,” 2021 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), no. Section IV, pp. 73–90, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/SP40001.2021.00005.

- A. Ham, D. Similien, S. Baek and G. York, "Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): Persistent Surveillance for a Military Scenario," 2022 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), pp. 1411-1417, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICUAS54217.2022.9836099.

- E. P. De Freitas, T. Heimfarth, A. Vinel, F. R. Wagner, C. E. Pereira, and T. Larsson, “Cooperation among wirelessly connected static and mobile sensor nodes for surveillance applications,” Sensors, vol. 13, no. 10, pp. 12903-12928, 2013, https://doi.org/10.3390/s131012903.

- J. Chen, J. Xu and L. Zhong, "Limited Intervention Collaborative Decision Making of MAV-UAV Team Based on VFCM," 2016 IEEE International Conference on Services Computing (SCC), pp. 876-879, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1109/SCC.2016.128.

- F. Saffre, H. Hildmann, H. Karvonen, and T. Lind, “Self-swarming for multi-robot systems deployed for situational awareness,” In New Developments and Environmental Applications of Drones: Proceedings of FinDrones 2020, pp. 51-72, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77860-6_3.

- S. Zhang and H. Duan, “Multiple UCAVs Target Assignment via Bloch Quantum-Behaved Pigeon-Inspired Optimization,” In Proceedings of the 2015 34th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), pp. 6936–6941, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1109/ChiCC.2015.7260736.

- T. Kaymal, "Unmanned aircraft systems for maritime operations: choosing "a" good design for achieving operational effectiveness," 2016 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Arlington, VA, USA, 2016, pp. 763-768, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICUAS.2016.7502634.

- N. J. Shih and Y. H. Qiu, “Resolving the urban dilemma of two adjacent rivers through a dialogue between GIS and augmented reality (AR) of fabrics,” Remote Sensing, vol. 14, no. 17, p. 4330, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14174330.

- J. Boisvert, M. A. Drouin, G. Godin, and M. Picard, “Augmented reality, 3D measurement, and thermal imagery for computer-assisted manufacturing,” In Emerging Digital Micromirror Device Based Systems and Applications XII, vol. 11294, pp. 108-115, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2545382.

- A. S. Brandão, D. Smrcka, É. Pairet, T. Nascimento and M. Saska, "Side-Pull Maneuver: A Novel Control Strategy for Dragging a Cable-Tethered Load of Unknown Weight Using a UAV," in IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 9159-9166, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2022.3190092.

- J. Tan, Y. Fan, P. Yan, C. Wang, and H. Feng, “Sliding Mode Fault Tolerant Control for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle with Sensor and Actuator Faults,” Sensors, vol. 19, p. 643, 2019, https://doi.org/10.3390/s19030643.

- A. Shafique, A. Mehmood and M. Elhadef, "Survey of Security Protocols and Vulnerabilities in Unmanned Aerial Vehicles," in IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 46927-46948, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3066778.

- V. Hassija et al., "Fast, Reliable, and Secure Drone Communication: A Comprehensive Survey," in IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 2802-2832, Fourthquarter 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2021.3097916.

- B. Balon and M. Simić, "Using Raspberry Pi Computers in Education," 2019 42nd International Convention on Information and Communication Technology, Electronics and Microelectronics (MIPRO), pp. 671-676, 2019, https://doi.org/10.23919/MIPRO.2019.8756967.

- M. Moritz, T. Redlich, P. P. Grames and J. P. Wulfsberg, "Value creation in open-source hardware communities: Case study of Open Source Ecology," 2016 Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering and Technology (PICMET), pp. 2368-2375, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1109/PICMET.2016.7806517.

Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, Vol. 7, No. 2, June 2025, pp. 138-146