Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro ISSN: 2685-9572

Transformer Models in Deep Learning: Foundations, Advances, Challenges and Future Directions

Iis Setiawan Mangkunegara 1, Purwono 2, Alfian Ma’arif 3, Noorulden Basil 4, Hamzah M. Marhoon 5, Abdel-Nasser Sharkawy 6,7

1 Department of Information Technology, Universitas Harapan Bangsa, Indonesia

2 Department of Informatics, Universitas Harapan Bangsa, Indonesia

3 Department of Electrical Engineering, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

4 Department of Electrical Engineering, College of Engineering, Mustansiriyah University, Baghdad, Iraq

5 Department of Automation Engineering and Artificial Intelligence, College of Information Engineering,

Al-Nahrain University, Jadriya, Baghdad, Iraq

6 Mechanical Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, South Valley University, Qena 83523, Egypt

7 Mechanical Engineering Department, College of Engineering, Fahad Bin Sultan University, Tabuk 47721, Saudi Arabia

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 19 March 2025 Revised 06 May 2025 Accepted 24 June 2025 |

|

Transformer models have significantly advanced deep learning by introducing parallel processing and enabling the modeling of long-range dependencies. Despite their performance gains, their high computational and memory demands hinder deployment in resource-constrained environments such as edge devices or real-time systems. This review aims to analyze and compare Transformer architectures by categorizing them into encoder-only, decoder-only, and encoder-decoder variants and examining their applications in natural language processing (NLP), computer vision (CV), and multimodal tasks. Representative models BERT, GPT, T5, ViT, and MobileViT are selected based on architectural diversity and relevance across domains. Core components including self-attention mechanisms, positional encoding schemes, and feed-forward networks are dissected using a systematic review methodology, supported by a visual framework to improve clarity and reproducibility. Performance comparisons are discussed using standard evaluation metrics such as accuracy, F1-score, and Intersection over Union (IoU), with particular attention to trade-offs between computational cost and model effectiveness. Lightweight models like DistilBERT and MobileViT are analyzed for their deployment feasibility. Major challenges including quadratic attention complexity, hardware constraints, and limited generalization are explored alongside solutions such as sparse attention mechanisms, model distillation, and hardware accelerators. Additionally, ethical aspects including fairness, interpretability, and sustainability are critically reviewed in relation to Transformer adoption across sensitive domains. This study offers a domain-spanning overview and proposes practical directions for future research aimed at building scalable, efficient, and ethically aligned. Transformer-based systems suited for mobile, embedded, and healthcare applications. |

Keywords: Transformer; Self-Attention; Natural Language Processing; Deep Learning; Models |

Corresponding Author: Purwono, Universitas Harapan Bangsa, Purwokerto, Indonesia. Email: purwono@uhb.ac.id |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: I. S. Mangkunegara, P. Purwono, A. Ma’arif, N. Basil, H. M. Marhoon, and A.-N. Sharkawy, “Transformer Models in Deep Learning: Foundations, Advances, Challenges and Future Directions,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 231-241, 2025, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v7i2.13053. |

- INTRODUCTION

In recent years, Transformer has been recognized as one of the most significant breakthroughs in the development of deep learning, particularly in sequential and structured data processing. Transformer architecture has reshaped modern deep learning models across NLP, vision, and speech, setting new benchmarks in both academic and industrial applications. This architecture was first introduced by Vaswani et al. in 2017 through a paper titled “Attention is All You Need”, and has since been widely used to replace traditional approaches such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) [1]. The paper introduced self-attention as a mechanism to replace recurrence, allowing global dependency modeling and parallelized training. The main innovation offered by Transformer lies in its self-attention mechanism, which allows long-term contextual relationships in data sequences to be modeled more effectively [2][3].

In contrast to RNNs that process data sequentially, the Transformer is designed to enable parallel processing, allowing for faster and more efficient model training [4]. This parallelism not only accelerates training but also facilitates scaling to massive datasets, making it suitable for large-scale applications such as web-scale language models. Alternative architectures such as LSTM with attention or hybrid RNN-transformer models have been proposed to address these limitations, offering better efficiency in constrained tasks. This advantage has been utilized to build large-scale models capable of achieving state-of-the-art performance in various tasks, including the development of Large Language Models (LLM) such as GPT, BERT, and T5 [5]. Among Transformer variants, BERT excels in masked language modeling, GPT is designed for autoregressive generation, and T5 unifies various NLP tasks under a text-to-text framework. In addition to speeding up the training process, this architecture has also improved the generalization ability of the model in handling high data complexity [6].

Along with the widespread application of Transformers, adaptations to various application domains have been made. In natural language processing, Transformers have powered tasks like summarization and translation. In computer vision, models like ViT have shown promising results. Time-series analysis and multimodal tasks have also benefited from attention-based representations [7][8]. On the other hand, in time-series analysis, the Transformer has been applied to tasks such as stock price forecasting and human activity recognition, and superior results over conventional methods have been reported [9]. In addition, Transformers have also been utilized in multimodal learning to integrate information from different types of data such as text, image, and voice simultaneously [10]-[12].

Despite the advantages offered by Transformers, a number of technical challenges still need to be overcome. The need for high computational resources and large memory consumption have been identified as major constraints in the application of this architecture, especially in resource-constrained devices such as edge devices and real-time systems [13][14]. Recent research has explored solutions such as model pruning, quantization, and low-rank factorization to mitigate these challenges. In addition, the structural complexity of Transformer architectures often makes optimization and deployment difficult in the context of practical applications [15][16]. Therefore, an in-depth understanding of the advantages, limitations, and development trends of Transformers is crucial to drive more efficient and applicable innovations in the future.

This article presents a comprehensive overview of the Transformer architecture and its foundational principles. The evolution of its design, along with various architectural variants developed to meet diverse application needs, is discussed systematically. Implementation challenges frequently encountered in practical scenarios are identified and critically analyzed. Furthermore, emerging application trends of Transformer models across multiple disciplines and industry sectors are highlighted to inform and guide future research and development efforts. This review uniquely integrates domain-wide analysis with a focus on lightweight adaptation and deployment efficiency, offering a structured roadmap for future Transformer development.

- TRANSFORMER ARCHITECTURE

- Basic Technology

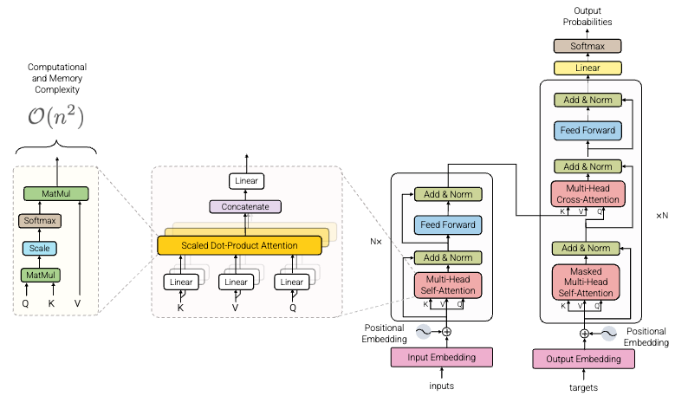

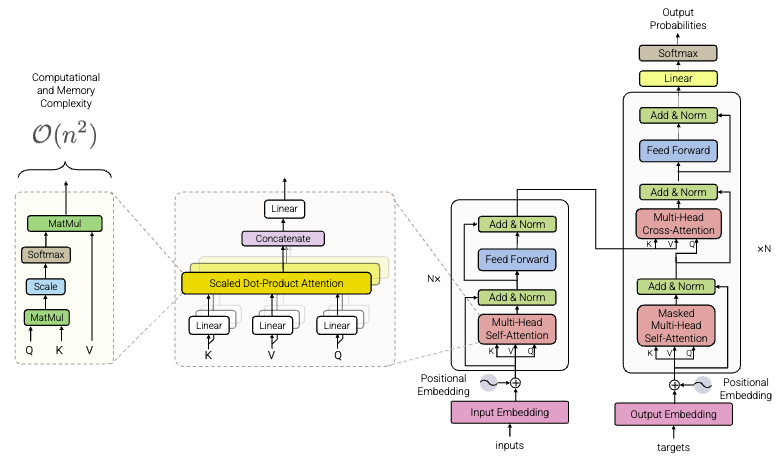

One of the key innovations in the Transformer architecture lies in the implementation of the self-attention mechanism, which enables the assessment of the relative importance between each element in a sequence to be done effectively [17]. Through this mechanism, the contextual information of each token with respect to other tokens can be thoroughly considered, without relying on a strict sequence structure as in previous models. To calculate attention scores, three main vectors are used, namely Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V) [18]. These scores are then used to direct the model's focus on the part of the input that is most relevant to a particular context [19]. Unlike traditional mechanisms that rely on local dependencies, the Q, K, V self-attention structure allows direct computation of global relationships between all elements in a sequence, enhancing representational power and reducing sequential bottlenecks. Equation (1) refers to the calculation on the concept of self-attention.

|

| (1) |

In addition to the ability to capture long-term dependencies, Transformer is also designed to support fully parallel processing. This parallelism significantly reduces training time and makes Transformer models scalable for massive datasets, a critical factor in training large language models (LLMs). Unlike Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) that process inputs sequentially, Transformer processes all tokens in a sequence simultaneously. This approach allows the training and inference process to be done in a much more time-efficient manner [17].

To enrich the representation of relations between tokens, multi-head attention is used, where multiple attention heads are operated in parallel to capture various relational perspectives in the data. Each head works independently, and the results are consolidated through a concatenation process followed by a linear transformation, thus obtaining a more informative and contextualized final representation [20]. The concatenated output is then projected through a learnable linear transformation to combine multiple attention heads into a single representation with consistent dimensions. Formula (2) is a representation of multi head attention.

|

| (2) |

With

Because Transformer does not have an explicit internal structure for representing positional order as in RNN, positional encoding is added to the input embedding vector [21]. This addition is done so that the relative position information between tokens remains available to the model, so that the data sequence can still be implicitly understood during the attention process [22]. A common choice is sinusoidal positional encoding, where each position is represented by a combination of sine and cosine functions at varying frequencies, enabling the model to distinguish relative positions without additional parameters.

- Architecture

The Transformer's initial architecture was designed based on an encoder-decoder structure composed of multiple iterative layers in each of its components [23]. In this design, the input sequence is first processed by the encoder module, and then the results are utilized by the decoder module to generate the output sequence incrementally. This separation allows input information processing and output generation to be done in a modular yet integrated manner. The interaction between the two modules is mediated through a cross-attention mechanism, which allows the encoded input representation to be used to contextually guide the decoding process [24]. Details of the architecture can be seen in Figure 1.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the Transformer consists of stacked encoder and decoder layers, each encoder layer is designed to capture the internal relationships between elements in the input sequence through two main components: multi-head self-attention and position-wise feed-forward network [25][26]. The self-attention component is responsible for modeling dependencies between tokens, regardless of the positional distance between them [27]. Meanwhile, the feed-forward component is in charge of transforming the attentional representation into more abstract and non-linear features [23]. To maintain training stability and facilitate gradient propagation, residual connections and layer normalization are also applied to each sub-layer [28]. Residual connections help mitigate vanishing gradients, while layer normalization accelerates convergence by stabilizing the training dynamics.

The self-attention mechanism forms the backbone of this architecture, where each token is given the ability to access information from other tokens in the sequence directly [29]. Through query, key, and value vectors, an attention score is calculated to determine the relative contribution of each token to the final representation. This mechanism allows the global context of the sequence to be modeled efficiently, even for long sequences, which was previously a major drawback of RNN models [30].

The decoder layer structure, on the other hand, is designed by maintaining the basic components of the encoder, but with the addition of one additional multi-head attention block [31]. This block allows the decoder to focus attention on the output of the encoder, so that important information from the input can be utilized during the output generation process [32]. In addition, masked attention is applied to the self-attention in the decoder section to maintain autoregressive properties, such that tokens in the current position do not have access to tokens that have not yet been generated [33]. This is important in maintaining sequence validity during inference. Masked self-attention in the decoder ensures that predictions are conditioned only on previous tokens, enabling effective autoregressive language modeling.

At each layer, in both the encoder and decoder, a feed-forward network (FFN) is inserted after the attention module. The FFN consists of two linear transformations separated by a non-linear activation function, typically ReLU [34][35]. The FFN typically consists of two linear transformations with a hidden layer dimension of 2048 and an output size equal to the model dimension. This function is independent of token position, and is applied identically to each token in the sequence. The aim is to increase the non-linear capacity of the model as well as strengthen the separation of local features that have been encoded by previous attentional blocks.

Overall, the Transformer architecture integrates attention and non-linear transformation capabilities in an iterative structure that can be parallelized very well. This design flexibility not only improves training efficiency, but also enables extension to various application domains such as computer vision, time series, and multimodal learning. The modular encoder-decoder design also facilitates the adaptation of this architecture to various input-output scenarios, whether in the context of classification, generation, or sequence-to-sequence mapping.

Encoder-only models, such as BERT, are typically used for tasks that require full input context understanding, like text classification or named entity recognition. Decoder-only models, such as GPT, are optimized for generative tasks, where text is produced one token at a time. Meanwhile, full encoder-decoder architectures, such as T5 or Transformer-based translation models, are well-suited for sequence-to-sequence tasks like machine translation or summarization, where an input sequence is mapped to a different output sequence.

Figure 1. Standard Transformer Architecture

- Architectural Evolution and Variation

- NLP-based Variants

Transformer architectures have revolutionized the field of natural language processing (NLP) through the development of various model variants that excel in tasks such as text classification, sentiment analysis, translation, and question answering [36]. Models such as BERT, GPT, and T5 became important milestones, each with bidirectional, generative, and text-to-text format approaches [37]. For efficiency, variants such as Longformer and Performer were designed to handle long sequences with lower complexity [38], while domain-specific adaptations were also made, as in Relphormer for knowledge graphs and Transformer models in bioinformatics [39][40].

In additional to large models, lightweight variants such as DistilBERT, TinyBERT, and MobileBERT were developed for devices with limited resources [41]. Transformers are also applied to specialized applications, such as Transformer-XL for automatic speech recognition [42], IndoBERT for Indonesian sentiment analysis [43], and SecurityBERT for cyber threat detection in IoT networks [44]. These variants demonstrate the flexibility of the Transformer architecture in various NLP contexts and implementation needs. Table 1 is a summary of the NLP variants that use Transformer.

Table 1. Summary of Transformer Development in the Natural Language Processing Field

Variant | Key Features | Applications |

BERT | Bidirectional language modeling | Text classification, sentiment analysis |

GPT | Generative text modeling | Text generation |

T5 | Text-to-text approach | Translation, summarization |

Longformer | Efficient long-sequence handling | Long-range attention tasks |

Performer | Kernel-based attention approximation | Efficient attention mechanism |

DistilBERT | Compact and efficient | Low-resource NLP tasks |

IndoBERT | High performance in sentiment analysis | Sentiment analysis |

SecurityBERT | Cyber threat detection | IoT cybersecurity |

Relphormer | Knowledge graph representation | Knowledge graph tasks |

Transformer-XL | Improved ASR performance | Automatic Speech Recognition |

- Vision Based Transformer

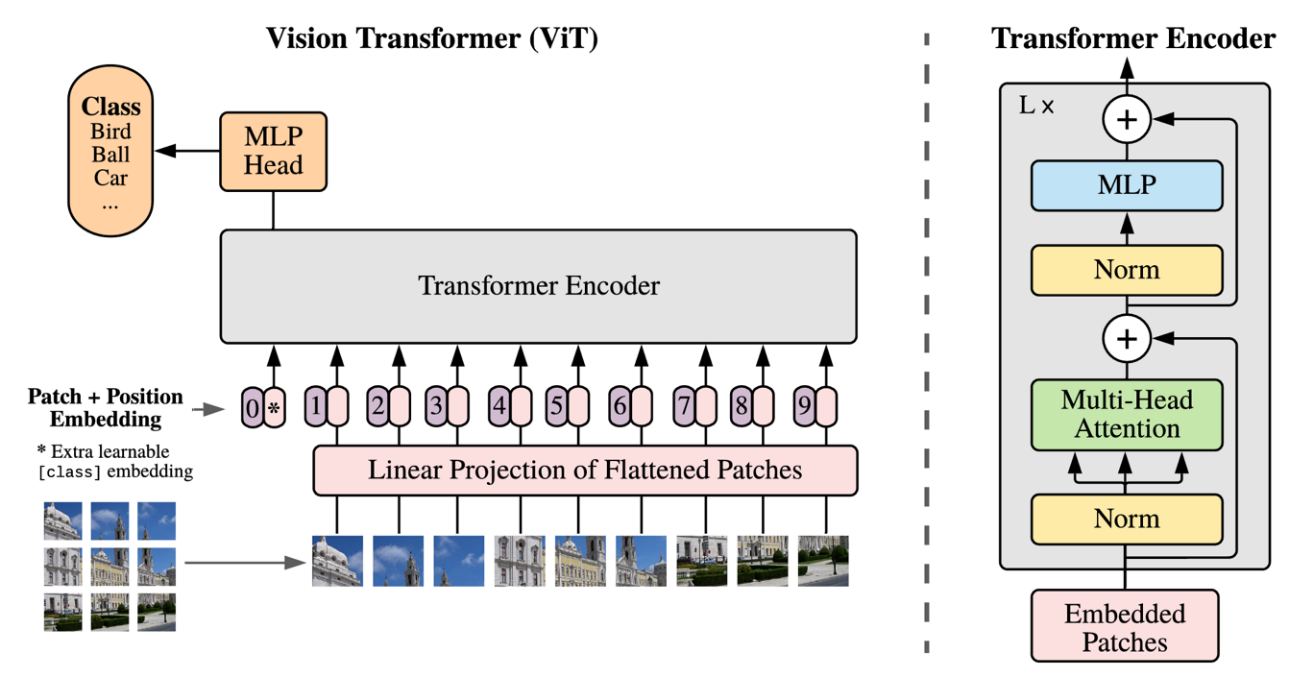

The application of Transformer architecture to computer vision is realized through the development of Vision Transformer (ViT), which defines a new paradigm in digital image processing. Unlike CNNs that use local convolutions to extract spatial features, ViT processes an image by dividing it into small fixed-size patches, then flattening each patch into a vector and mapping it into the embedding space using linear projection [45]. The set of patch tokens, coupled with classification tokens ([CLS]) and positional embedding [46], are then processed through several Transformer encoder blocks consisting of a multi-head self-attention mechanism and feed-forward network, respectively [47]. This approach allows the model to capture global spatial relationships across the image from an early stage, different from the stepwise hierarchy in CNN. The ViT architecture can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Architecture of the Vision Based Transformer

Although the ViT architecture offers high representation flexibility and efficient computational parallelization, its success is highly dependent on data scale and training resources [32]. Without inductive biases such as locality and translation invariance that CNN possesses, ViT requires large datasets and strong regularization strategies in order to generalize well [48]. However, in benchmark experiments such as ImageNet, ViT has shown competitive performance and even outperformed conventional CNNs in classification and segmentation tasks when trained with large-scale pretraining [45].

To bridge the efficiency and scalability limitations of ViT, a number of advanced architectural variants have been developed, such as Swin Transformer, BEiT, and DeiT. Swin Transformer introduces window-based local attention that is shifted between layers, enabling hierarchical learning with lower complexity [49]. BEiT adopts a masked image modeling-type pretraining scheme similar to BERT, but applied to visual tokens [50]. On the other hand, DeiT is specifically designed to be efficiently trained on medium-sized datasets with the help of token distillation, making it an ideal solution for resource-constrained scenarios [51]. Overall, these architectures have reinforced Transformer's position as a strong and flexible alternative foundation in the modern computer vision ecosystem.

- Efficient and Lightweight Transformer

The growing demand for computational efficiency, especially in the context of deployment on resource-constrained devices such as edge devices and real-time systems, has led to the development of various lightweight Transformer variants. Architectures such as MobileViT and Linformer have been designed to effectively maintain contextual representation capabilities, but with lower computation complexity than conventional Transformers [52][53]. In MobileViT, the Transformer module has been integrated into a lightweight convolutional framework, thus benefiting from both the global representation advantages of the Transformer and the spatial efficiency of CNNs. Meanwhile, Linformer adopts a linear projection approach with a low-rank approximation to the attention matrix, which enables the reduction of memory complexity  to

to  , without significant performance degradation.

, without significant performance degradation.

To further improve efficiency, a number of additional strategies have been implemented, including sparsity, quantization, and kernelized attention techniques [54]-[56]. Through these approaches, full attention can be approached computationally with a much lighter load. For example, architectures such as Performer have used kernel-based approximations to represent attention in long sequences with better time and space efficiency. Such strategies enable Transformer to be used in real-time and embedded scenarios, where computational efficiency is a critical factor.

In addition to architectural optimization, knowledge distillation-based approaches have also been widely adopted to generate small yet competitive Transformer models [57]. In this approach, large pre-trained models (teacher models) are used to transfer knowledge to smaller models (student models), with the aim of maintaining accuracy while reducing the number of parameters and inference time. Models such as DistilBERT, TinyBERT, MobileBERT, and MiniLM are the result of the distillation process that have successfully maintained high performance on various NLP tasks, despite being run in a limited computing environment [58]. With the combined application of distillation techniques and efficient architecture design, the lightweight Transformer has been positioned as a relevant solution for various modern applications that require high performance with minimal computational footprint.

- METRIC EVALUATION

Evaluating the performance of Transformer architectures is generally done by considering a number of aspects, including prediction accuracy, computational efficiency, and generalizability to various application domains. In the field of natural language processing (NLP), metrics such as accuracy [59], F1-score [60], BLEU score [61], and perplexity [62] have been widely used to measure model quality in tasks such as classification, translation, and text generation. Meanwhile, in the computer vision domain, model performance is assessed using metrics such as Top-1 accuracy [63], mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) [64], and mean Average Precision (mAP) [65], depending on the type of task at hand, such as classification, segmentation, or object detection.

Besides the accuracy aspect, computational efficiency is also an important factor in assessing the feasibility of Transformer implementation, especially in production scenarios and on resource-constrained devices. Frequently used parameters include the number of model parameters [66], Floating Point Operations per Second (FLOPs) [67], inference time [68], and memory consumption [66]. Lightweight Transformer models such as MobileViT, TinyBERT, and Linformer are not only evaluated in terms of prediction accuracy, but also through efficiency measurements during the training and deployment process. Therefore, the trade-off between performance and efficiency is a crucial evaluative dimension in the development of modern architectures.

In addition to testing on standard benchmarks such as GLUE, SQuAD, and ImageNet, a number of studies have also evaluated the generalization capability of Transformer models on real-world data as well as specialized domains such as healthcare, bioinformatics, and cybersecurity. Qualitative evaluation and error analysis are often conducted to identify model limitations as well as potential biases in the prediction results [69]. With such a comprehensive evaluative approach, the performance of the Transformer architecture can be holistically assessed not only based on accuracy, but also the sustainability and effectiveness of its application in the context of real applications.

- CHALLENGES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The Transformer model, although successfully applied to various machine learning tasks, still faces a number of significant technical challenges. The quadratic complexity of the self-attention mechanism has led to high computational requirements, especially for long sequences and large-scale datasets [70]. For instance, processing a sequence of 10,000 tokens with a standard self-attention mechanism requires approximately 100 million attention computations, making it computationally prohibitive for long-document analysis or DNA sequence modeling. A consequence of this is the limited applicability of the Transformer on resource-constrained devices, such as Internet of Things (IoT) systems and edge devices [71]. These limitations are particularly evident in real-world settings such as wearable devices, edge AI cameras, and smart home assistants, where limited memory and compute power restrict the feasibility of deploying full-scale Transformer models.

In addition to algorithmic complexity, the need for hardware resources is also a major bottleneck. Unlike RNNs or LSTMs, which process input step-by-step and inherently maintain sequential state, Transformer models lack an iterative structure. This can lead to issues in tasks where temporal causality or recursive state representation is beneficial, such as sensor fusion or time-sensitive forecasting. Large computational capacity and memory are required for training and inference, which makes it difficult to implement on devices with limited power, including battery-powered devices and real-time applications [72][73]. On battery-powered systems such as mobile health monitors or autonomous drones, energy efficiency becomes critical. Transformer models with millions of parameters often require frequent offloading to servers or significant hardware optimization to maintain functionality. Large model sizes also impact energy consumption and environmental footprint. Although techniques such as weight pruning and compression have been developed to reduce such burden, performance degradation often still occur [71].

The non-iterative structure of Transformer has made replication difficult for traditional learning algorithms that rely on iterative processes. This makes the Transformer architecture less suitable for certain types of problems unless structural modifications are made. In addition, the difficulty in implementing Transformers on edge devices is also due to the need for low power consumption and high efficiency. To address this, hardware accelerators and reparameterization approaches have been developed [74]. Recent efforts have explored solutions such as hardware accelerators, reparameterization, and high-rank factorization. Reparameterization refers to restructuring model components such as replacing dense layers with more efficient alternatives to reduce computational cost while preserving functionality. High-rank factorization, on the other hand, decomposes large weight matrices into multiple smaller matrices, thereby reducing memory usage and speeding up matrix operations.

Various future research directions have been proposed to address these challenges. The development of accelerators such as Habana GAUDI and Ayaka has been directed towards improving energy efficiency and throughput over a wide range of input sizes [75]. In addition, approaches such as high-rank factorization (HRF) and de-HRF processes have been used to optimize the performance of lightweight Transformer models, making them more suitable for deployment on resource-constrained devices [71]. Efforts to integrate iterative characteristics into the Transformer design, such as through the development of looped Transformer architecture, have also been introduced as a solution to mimic the behavior of traditional iteration-based learning algorithms. On the other hand, distributed training strategies such as pipeline parallelism continue to be optimized to balance computational and memory load in large-scale training scenarios [76]. The expansion of Transformer applications to the domains of multimodal learning [77], industrial predictive maintenance [78][79], as well as energy forecasting, also opens up opportunities to strengthen the generalization of this architecture in various sectors. Although in some cases classical models such as Support Vector Regression (SVR) still show superiority [80], Transformers are expected to remain a key foundation in the development of efficient, adaptive, and cross-domain modern machine learning systems. These approaches aim to overcome current bottlenecks by improving computational efficiency, enhancing memory handling, and enabling real-time deployment especially critical for applications in autonomous vehicles, healthcare monitoring, and edge robotics. By addressing these core challenges, future Transformer designs can become more accessible, sustainable, and adaptable accelerating adoption across critical industries ranging from healthcare to autonomous systems.

- CONCLUSION

The Transformer architecture has been established as a key framework in the development of modern deep learning models. Unlike RNNs or LSTMs that rely on sequential data processing, the self-attention mechanism enables the Transformer to model long-range dependencies in parallel, improving both training speed and contextual understanding. Its superiority in handling sequential and spatial data through self-attention mechanisms allows long-term contextual relationships to be modeled efficiently. The parallel processing enabled by this architecture has also improved the speed of training and generalization of models on various tasks, particularly in natural language processing, computer vision, and multimodal learning.

Various variants of Transformer have been developed to suit application needs and system efficiency, such as BERT, GPT, ViT, Swin Transformer, as well as lightweight models such as Linformer, MobileViT, and DistilBERT. Transformer variants can be broadly categorized into general-purpose models (e.g., BERT, GPT), vision-focused architectures (e.g., ViT), and lightweight designs optimized for efficiency (e.g., MobileViT, DistilBERT). Based on the performance evaluation, it has been demonstrated that high accuracy can be achieved, but it is still overshadowed by large resource requirements and high inference complexity, especially in computationally constrained environments. Lightweight Transformer models are particularly advantageous for deployment in mobile NLP applications, wearable health monitoring systems, or embedded devices where latency and power constraints are critical.

Several technical challenges remain to be overcome, including quadratic complexity of attention, limitations of non-iterative architectures, and barriers to deployment on edge devices. However, the non-iterative nature of the Transformer can limit its ability to model sequential dependencies where temporal ordering is crucial, posing challenges for tasks requiring real-time feedback or continuous learning. For this reason, future research is directed towards developing more efficient structures, utilizing distillation techniques, more adaptive multimodal integration, and the use of hardware accelerators. Among the emerging directions, sparse attention mechanisms show great promise in reducing computational overhead while maintaining performance, especially for processing long sequences. In addition to technical aspects, attention is also being paid to energy sustainability, model bias, and system transparency. Future development must also prioritize ethical aspects such as fairness, sustainability, and transparency to ensure that Transformer-based systems contribute positively and equitably in real-world deployments, particularly in sensitive domains like healthcare and governance. By addressing these challenges, Transformer is expected to continue to be developed into an efficient, responsible artificial intelligence solution that can be widely implemented in various critical sectors, both academic and industrial.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to express their deepest appreciation and gratitude to the community of Peneliti Teknologi Teknik Indonesia (PTTI) and Universitas Harapan Bangsa (UHB) for their scientific contributions, scientific discussions, and reference sources that were very helpful in the preparation and improvement of this article. The support in the form of literature access, technical input, and collaborative networking provided has added significant value to the quality of the study presented.

REFERENCES

- I. Dirgová Luptáková, M. Kubovčík, and J. Pospíchal, “Wearable Sensor-Based Human Activity Recognition with Transformer Model,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 5, p. 1911, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/s22051911.

- Y. Wang, “Research and Application of Machine Learning Algorithm in Natural Language Processing and Semantic Understanding,” in 2024 International Conference on Telecommunications and Power Electronics (TELEPE), pp. 655–659, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/TELEPE64216.2024.00123.

- X. Chen, “The Advance of Deep Learning and Attention Mechanism,” in 2022 International Conference on Electronics and Devices, Computational Science (ICEDCS), pp. 318–321, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICEDCS57360.2022.00078.

- J. W. Chan and C. K. Yeo, “A Transformer based approach to electricity load forecasting,” The Electricity Journal, vol. 37, no. 2, p. 107370, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tej.2024.107370.

- A. Di Ieva, C. Stewart, and E. Suero Molina, “Large Language Models in Neurosurgery,” pp. 177–198, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-64892-2_11.

- S. Islam et al., “A comprehensive survey on applications of transformers for deep learning tasks,” Expert Syst Appl, vol. 241, p. 122666, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122666.

- T. Zhang, W. Xu, B. Luo, and G. Wang, “Depth-Wise Convolutions in Vision Transformers for efficient training on small datasets,” Neurocomputing, vol. 617, p. 128998, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2024.128998.

- A. Sriwastawa and J. A. Arul Jothi, “Vision transformer and its variants for image classification in digital breast cancer histopathology: a comparative study,” Multimed Tools Appl, vol. 83, no. 13, pp. 39731–39753, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-023-16954-x.

- C. M. Thwal, Y. L. Tun, K. Kim, S.-B. Park, and C. S. Hong, “Transformers with Attentive Federated Aggregation for Time Series Stock Forecasting,” in 2023 International Conference on Information Networking (ICOIN), pp. 499–504, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICOIN56518.2023.10048928.

- B. T. Hung and N. H. M. Thu, “Novelty fused image and text models based on deep neural network and transformer for multimodal sentiment analysis,” Multimed Tools Appl, vol. 83, no. 25, pp. 66263–66281, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-023-18105-8.

- T. G. Altundogan, M. Karakose, and S. Tanberk, “Transformer Based Multimodal Summarization and Highlight Abstraction Approach for Texts and Speech Audios,” in 2024 28th International Conference on Information Technology (IT), pp. 1–4, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/IT61232.2024.10475775.

- B. Kashyap, P. Aswini, V. H. Raj, K. Pithamber, R. Sobti, and Z. Salman, “Integration of Vision and Language in Multi-Mode Video Converters (Partially) Aligns with the Brain,” in 2024 Second International Conference Computational and Characterization Techniques in Engineering & Sciences (IC3TES), pp. 1–6, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/IC3TES62412.2024.10877464.

- V. Pandelea, E. Ragusa, T. Apicella, P. Gastaldo, and E. Cambria, “Emotion Recognition on Edge Devices: Training and Deployment,” Sensors, vol. 21, no. 13, p. 4496, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/s21134496.

- F. Liu et al., “Vision Transformer-based overlay processor for Edge Computing,” Appl Soft Comput, vol. 156, p. 111421, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2024.111421.

- N. Penkov, K. Balaskas, M. Rapp, and J. Henkel, “Differentiable Slimming for Memory-Efficient Transformers,” IEEE Embed Syst Lett, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 186–189, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/LES.2023.3299638.

- S. Tuli and N. K. Jha, “EdgeTran: Device-Aware Co-Search of Transformers for Efficient Inference on Mobile Edge Platforms,” IEEE Trans Mob Comput, vol. 23, no. 6, pp. 7012–7029, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/TMC.2023.3328287.

- O. A. Sarumi and D. Heider, “Large language models and their applications in bioinformatics,” Comput Struct Biotechnol J, vol. 23, pp. 3498–3505, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2024.09.031.

- B. Rahmadhani, P. Purwono, and Safar Dwi Kurniawan, “Understanding Transformers: A Comprehensive Review,” Journal of Advanced Health Informatics Research, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 85–94, 2024, https://doi.org/10.59247/jahir.v2i2.292.

- H. Yeom and K. An, “A Simplified Query-Only Attention for Encoder-Based Transformer Models,” Applied Sciences, vol. 14, no. 19, p. 8646, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/app14198646.

- J. Liu, W. Sun, and X. Gao, “Ship Classification Using Swin Transformer for Surveillance on Shore,” pp. 774–785, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-3927-3_76.

- J. Yeom, T. Kim, R. Chang, and K. Song, “Structural and positional ensembled encoding for Graph Transformer,” Pattern Recognit Lett, vol. 183, pp. 104–110, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patrec.2024.05.006.

- J. Su, M. Ahmed, Y. Lu, S. Pan, W. Bo, and Y. Liu, “RoFormer: Enhanced transformer with Rotary Position Embedding,” Neurocomputing, vol. 568, p. 127063, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2023.127063.

- Y. Yin, Z. Tang, and H. Weng, “Application of visual transformer in renal image analysis,” Biomed Eng Online, vol. 23, no. 1, p. 27, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12938-024-01209-z.

- Z. Li, R. Liu, L. Sun, and Y. Zheng, “Multi-Feature Cross Attention-Induced Transformer Network for Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data Classification,” Remote Sens (Basel), vol. 16, no. 15, p. 2775, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs16152775.

- Y. Wang, Y. Liu, and Z.-M. Ma, “The scale-invariant space for attention layer in neural network,” Neurocomputing, vol. 392, pp. 1–10, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2020.01.090.

- I.-Y. Kwak et al., “Proformer: a hybrid macaron transformer model predicts expression values from promoter sequences,” BMC Bioinformatics, vol. 25, no. 1, p. 81, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-024-05645-5.

- A. Kumar, C. Barla, R. K. Singh, A. Kant, and D. Kumar, “Exploratory Study on Different Transformer Models,” In International Conference on Advanced Network Technologies and Intelligent Computing, pp. 32–45, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-83796-8_3.

- A. Zaeemzadeh, N. Rahnavard, and M. Shah, “Norm-Preservation: Why Residual Networks Can Become Extremely Deep?,” IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell, vol. 43, no. 11, pp. 3980–3990, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2020.2990339.

- S. Islam et al., “A comprehensive survey on applications of transformers for deep learning tasks,” Expert Syst Appl, vol. 241, p. 122666, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122666.

- M. Gao, H. Zhao, and M. Deng, “A Novel Convolution Kernel with Multi-head Self-attention,” in 2023 8th International Conference on Intelligent Informatics and Biomedical Sciences (ICIIBMS), pp. 417–420, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIIBMS60103.2023.10347796.

- H. Ding, K. Chen, and Q. Huo, “An Encoder-Decoder Approach to Handwritten Mathematical Expression Recognition with Multi-head Attention and Stacked Decoder,” pp. 602–616, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86331-9_39.

- J. Wang, C. Lai, Y. Wang, and W. Zhang, “EMAT: Efficient feature fusion network for visual tracking via optimized multi-head attention,” Neural Networks, vol. 172, p. 106110, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2024.106110.

- R. Rende, F. Gerace, A. Laio, and S. Goldt, “Mapping of attention mechanisms to a generalized Potts model,” Phys Rev Res, vol. 6, no. 2, p. 023057, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevResearch.6.023057.

- J. Tang, S. Wang, S. Chen, and Y. Kang, “DP-FFN: Block-Based Dynamic Pooling for Accelerating Feed-Forward Layers in Transformers,” in 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), pp. 1–5, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/ISCAS58744.2024.10558119.

- Y. Yu, K. Adu, N. Tashi, P. Anokye, X. Wang, and M. A. Ayidzoe, “RMAF: Relu-Memristor-Like Activation Function for Deep Learning,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 72727–72741, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2987829.

- M. Al Hamed, M. A. Nemer, J. Azar, A. Makhoul, and J. Bourgeois, “Evaluating Transformer Architectures for Fault Detection in Industry 4.0: A Multivariate Time Series Classification Approach,” in 2025 5th IEEE Middle East and North Africa Communications Conference (MENACOMM), pp. 1–6, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1109/MENACOMM62946.2025.10911019.

- S. K. Assayed, M. Alkhatib, and K. Shaalan, “A Transformer-Based Generative AI Model in Education: Fine-Tuning BERT for Domain-Specific in Student Advising,” pp. 165–174, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-65996-6_14.

- Y. Akimoto, K. Fukuchi, Y. Akimoto, and J. Sakuma, “Privformer: Privacy-preserving Transformer with MPC,” in 2023 IEEE 8th European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P), pp. 392–410, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/EuroSP57164.2023.00031.

- Z. Bi, S. Cheng, J. Chen, X. Liang, F. Xiong, and N. Zhang, “Relphormer: Relational Graph Transformer for Knowledge Graph Representations,” Neurocomputing, vol. 566, p. 127044, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2023.127044.

- M. E. Mswahili and Y.-S. Jeong, “Transformer-based models for chemical SMILES representation: A comprehensive literature review,” Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 20, p. e39038, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e39038.

- Y. Z. Vakili, A. Fallah, and H. Sajedi, “Distilled BERT Model in Natural Language Processing,” in 2024 14th International Conference on Computer and Knowledge Engineering (ICCKE), pp. 243–250, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCKE65377.2024.10874673.

- A. Jain, A. Rouhe, S.-A. Grönroos, and M. Kurimo, “Finnish ASR with Deep Transformer Models,” in Interspeech 2020, pp. 3630–3634, 2020, https://doi.org/10.21437/Interspeech.2020-1784.

- I. Daqiqil ID, H. Saputra, S. Syamsudhuha, R. Kurniawan, and Y. Andriyani, “Sentiment analysis of student evaluation feedback using transformer-based language models,” Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, vol. 36, no. 2, p. 1127, 2024, https://doi.org/10.11591/ijeecs.v36.i2.pp1127-1139.

- M. A. Ferrag et al., “Revolutionizing Cyber Threat Detection With Large Language Models: A Privacy-Preserving BERT-Based Lightweight Model for IoT/IIoT Devices,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 23733–23750, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3363469.

- O. Elharrouss et al., “ViTs as backbones: Leveraging vision transformers for feature extraction,” Information Fusion, vol. 118, p. 102951, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2025.102951.

- Y. Li et al., “How Does Attention Work in Vision Transformers? A Visual Analytics Attempt,” IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph, vol. 29, no. 6, pp. 2888–2900, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2023.3261935.

- G. L. Baroni, L. Rasotto, K. Roitero, A. H. Siraj, and V. Della Mea, “Vision Transformers for Breast Cancer Histology Image Classification,” pp. 15–26, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-51026-7_2.

- J. Chen, P. Wu, X. Zhang, R. Xu, and J. Liang, “Add-Vit: CNN-Transformer Hybrid Architecture for Small Data Paradigm Processing,” Neural Process Lett, vol. 56, no. 3, p. 198, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11063-024-11643-8.

- Z. Liang, J. Liu, J. Zhang, and J. Zhao, “High Performance Target Detection Based on Swin Transformer,” in 2024 2nd International Conference on Signal Processing and Intelligent Computing (SPIC), pp. 1077–1080, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/SPIC62469.2024.10691413.

- S. Pak et al., “Application of deep learning for semantic segmentation in robotic prostatectomy: Comparison of convolutional neural networks and visual transformers,” Investig Clin Urol, vol. 65, no. 6, p. 551, 2024, https://doi.org/10.4111/icu.20240159.

- H. Rangwani, P. Mondal, P. Mondal, M. Mishra, A. R. Asokan, and R. V. Babu, “DeiT-LT: Distillation Strikes Back for Vision Transformer Training on Long-Tailed Datasets,” in 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 23396–23406, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR52733.2024.02208.

- L. Liming, F. Yao, L. Pengwei, and L. Renjie, “Remote sensing image object detection based on MobileViT and multiscale feature aggregation,” CAAI Transactions on Intelligent Systems, vol. 19, no. 5, pp. 1168–1177, 2024, https://doi.org/10.11992/tis.202310022.

- S. Islam et al., “A comprehensive survey on applications of transformers for deep learning tasks,” Expert Syst Appl, vol. 241, p. 122666, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122666.

- M.-G. Lin, J.-P. Wang, Y.-J. Luo, and A.-Y. A. Wu, “A 28nm 64.5TOPS/W Sparse Transformer Accelerator with Partial Product-based Speculation and Sparsity-Adaptive Computation,” in 2024 IEEE Asia Pacific Conference on Circuits and Systems (APCCAS), pp. 664–668, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/APCCAS62602.2024.10808854.

- I. Zharikov, I. Krivorotov, V. Alexeev, A. Alexeev, and G. Odinokikh, “Low-Bit Quantization of Transformer for Audio Speech Recognition,” pp. 107–120, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-19032-2_12.

- Y. Chen, F. Tonin, Q. Tao, and J. A. K. Suykens, “Primal-Attention: Self-attention through Asymmetric Kernel SVD in Primal Representation,” In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 36, pp. 65088-65101, 2023, https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2023/hash/cd687a58a13b673eea3fc1b2e4944cf7-Abstract-Conference.html.

- A. Kolesnikova, Y. Kuratov, V. Konovalov, and M. Mikhail, “Knowledge Distillation of Russian Language Models with Reduction of Vocabulary,” in Computational Linguistics and Intellectual Technologies, pp. 295–310, 2022, https://doi.org/10.28995/2075-7182-2022-21-295-310.

- Y. Z. Vakili, A. Fallah, and H. Sajedi, “Distilled BERT Model in Natural Language Processing,” in 2024 14th International Conference on Computer and Knowledge Engineering (ICCKE), pp. 243–250, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCKE65377.2024.10874673.

- A. Nazir et al., “LangTest: A comprehensive evaluation library for custom LLM and NLP models,” Software Impacts, vol. 19, p. 100619, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.simpa.2024.100619.

- M. Harahus, Z. Sokolová, M. Pleva, and D. Hládek, “Evaluating BERT-Derived Models for Grammatical Error Detection Across Diverse Dataset Distributions,” in 2024 International Symposium ELMAR, pp. 237–240, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/ELMAR62909.2024.10694387.

- E. Reiter, “A Structured Review of the Validity of BLEU,” Computational Linguistics, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 393–401, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1162/coli_a_00322.

- E. Durmus, F. Ladhak, and T. Hashimoto, “Spurious Correlations in Reference-Free Evaluation of Text Generation,” in Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Paperspp. 1443–1454, 2022, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2022.acl-long.102.

- F. Yang and S. Koyejo, “On the consistency of top-k surrogate losses,” In International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 10727-10735, 2020, https://proceedings.mlr.press/v119/yang20f.html.

- W.-S. Jeon and S.-Y. Rhee, “MPFANet: Semantic Segmentation Using Multiple Path Feature Aggregation,” International Journal of Fuzzy Logic and Intelligent Systems, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 401–408, 2021, https://doi.org/10.5391/IJFIS.2021.21.4.401.

- B. Kaur and S. Singh, “Object Detection using Deep Learning,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Data Science, Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence, pp. 328–334, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1145/3484824.3484889.

- S. Tuli and N. K. Jha, “EdgeTran: Device-Aware Co-Search of Transformers for Efficient Inference on Mobile Edge Platforms,” IEEE Trans Mob Comput, vol. 23, no. 6, pp. 7012–7029, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/TMC.2023.3328287.

- Y. Gao, J. Zhang, S. Wei, and Z. Li, “PFormer: An efficient CNN-Transformer hybrid network with content-driven P-attention for 3D medical image segmentation,” Biomed Signal Process Control, vol. 101, p. 107154, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2024.107154.

- B. K. H. Samosir and S. M. Isa, “Evaluating Vision Transformers Efficiency in Image Captioning,” in 2024 International Conference on Intelligent Cybernetics Technology & Applications (ICICyTA), pp. 926–931, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICICYTA64807.2024.10913182.

- Y. Kumar, A. Ilin, H. Salo, S. Kulathinal, M. K. Leinonen, and P. Marttinen, “Self-Supervised Forecasting in Electronic Health Records With Attention-Free Models,” IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 5, no. 8, pp. 3926–3938, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/TAI.2024.3353164.

- Y. Qin et al., “Ayaka: A Versatile Transformer Accelerator With Low-Rank Estimation and Heterogeneous Dataflow,” IEEE J Solid-State Circuits, vol. 59, no. 10, pp. 3342–3356, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/JSSC.2024.3397189.

- Z. Zhang, Z. Dong, W. Xu, and J. Han, “Reparameterization of Lightweight Transformer for On-Device Speech Emotion Recognition,” IEEE Internet Things J, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 4169–4182, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2024.3483232.

- S. Gholami, “Can Pruning Make Large Language Models More Efficient?,” In Redefining Security With Cyber AI, pp. 1–14, 2024, https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-6517-5.ch001.

- S. Tuli and N. K. Jha, “TransCODE: Co-Design of Transformers and Accelerators for Efficient Training and Inference,” IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems, vol. 42, no. 12, pp. 4817–4830, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/TCAD.2023.3283443.

- B. Reidy, M. Mohammadi, M. Elbtity, H. Smith, and Z. Ramtin, “Work in Progress: Real-time Transformer Inference on Edge AI Accelerators,” in 2023 IEEE 29th Real-Time and Embedded Technology and Applications Symposium (RTAS), pp. 341–344, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/RTAS58335.2023.00036.

- C. Zhang et al., “Benchmarking and In-depth Performance Study of Large Language Models on Habana Gaudi Processors,” in Proceedings of the SC ’23 Workshops of the International Conference on High Performance Computing, Network, Storage, and Analysis, pp. 1759–1766, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1145/3624062.3624257.

- Z. Lu, F. Wang, Z. Xu, F. Yang, and T. Li, “On the Performance and Memory Footprint of Distributed Training: An Empirical Study on Transformers,” Softw Pract Exp, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1002/spe.3421.

- P. Xu, X. Zhu, and D. A. Clifton, “Multimodal Learning With Transformers: A Survey,” IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell, vol. 45, no. 10, pp. 12113–12132, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2023.3275156.

- E. Tamakloe, B. Kommey, J. J. Kponyo, E. T. Tchao, A. S. Agbemenu, and G. S. Klogo, “Predictive AI Maintenance of Distribution Oil‐Immersed Transformer via Multimodal Data Fusion: A New Dynamic Multiscale Attention CNN‐LSTM Anomaly Detection Model for Industrial Energy Management,” IET Electr Power Appl, vol. 19, no. 1, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1049/elp2.70011.

- A. W. S. Er, W. K. Wong, F. H. Juwono, I. M. Chew, S. Sivakumar, and A. P. Gurusamy, “Automated Transformer Health Prediction: Evaluation of Complexity and Linearity of Models for Prediction,” In International Conference on Green Energy, Computing and Intelligent Technology, 2024, pp. 21–33, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-9833-3_3.

- J. Huang and S. Kaewunruen, “Forecasting Energy Consumption of a Public Building Using Transformer and Support Vector Regression,” Energies (Basel), vol. 16, no. 2, p. 966, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/en16020966.

Transformer Models in Deep Learning: Foundations, Advances, Challenges and Future Directions

(Iis Setiawan Mangkunegara)