Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro ISSN: 2685-9572

Optimal Controller Design of Crowbar System for DFIG-based WT: Applications of Gravitational Search Algorithm

Amany Fayz Ali Ahmed 1, I. M. Elzein 2, Mohamed Metwally Mahmoud 1, Sid Ahmed El Mehdi Ardjoun 3, Ahmed M. Ewias 1, Usama Khaled 1

1 Electrical Engineering Department, Faculty of Energy Engineering, Aswan University, Aswan 81528, Egypt

2 Department of Electrical Engineering, College of Engineering and Technology, University of Doha for Science and Technology, Doha P.O. Box 24449, Qatar

3 IRECOM Laboratory, Faculty of Electrical Engineering, Djillali Liabes University, Sidi Bel–Abbes 22000, Algeria

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 15 March 2025 Revised 27 April 2025 Accepted 02 May 2025 |

|

The optimal output and efficacy of a doubly fed induction wind generator (DFIG) are dependent on a multitude of uncontrollable components, necessitating the use of an adequate control system. The crowbar system is essential to the system during abnormal events; thus, it requires appropriate control algorithms and enough control settings. This work suggests the gravitational search algorithm (GSA) to construct the crowbar controller. A synopsis of wind energy and a conversation about the pertinent DFIG component and its methodology. The outcomes acquired with the suggested optimized crowbar system are contrasted with those obtained with a traditional crowbar and without protection. The outcomes confirmed the higher performance of the suggested strategy. The DFIG system responds marginally improved to active and reactive (P&Q) power, DC-Link voltage (DCLV), and machine rotation when a GSA-based PI controller is used. Finally, it can be said that by maintaining the DCLV below the allowable value, which permits the high penetration possibilities of wind energy, the suggested technique assures fault ride-through capacity (FRTC). |

Keywords: Crowbar; DFIG; Gravitational Search Algorithm; FRT Capability; Wind Energy Control |

Corresponding Author: Mohamed Metwally Mahmoud, Electrical Engineering Department, Faculty of Energy Engineering, Aswan University, Aswan 81528, Egypt Email: metwally_m@aswu.edu.eg |

This work is open access under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: A. F. A. Ahmed, I. M. Elzein, M. M. Mahmoud, S. A. E. M. Ardjoun, A. M. Ewias, and U. Khaled, “Optimal Controller Design of Crowbar System for DFIG-based WT: Applications of Gravitational Search Algorithm,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 122-137, 2025, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v7i2.13027. |

- INTRODUCTION

Enterprises, governments, and research centers around the world are all interested in electrical energy, and there is a continuous discussion about which developed and developing nations should prioritize various forms of generating. The energy revolution that seeks to eradicate climate change has been the most essential applied development to ensure sustainable progress [1]-[3]. As fossil fuels continue to exhaust and worries about greenhouse gas emissions are on the rise, renewable energy technologies (RETs) exhibit an unparalleled growth. Leading this revolution are wind systems, which have been found to be low-cost, easy to implement, and highly scalable for various applications [4]-[7]. A few drawbacks of such technologies include variability of performance, integration into existing systems and maximizing the generation of power. Globally, energy source use is changing. IRENA reports that international renewable energy capacity expanded 80% from 2010 to 2020, mostly owing to solar and wind energy [8]-[10]. This quick increase revealed various constraints, including weather dependence, electric grid ‘ramp’ instabilities, and low energy user facilities. All of the above issues can be overcome using hybrid RETs that integrate multiple RETs with high-performance energy storage [11]-[13]. The global transition to RETs has varying implications across regions. Germany and Spain, for example, have achieved over 40% penetration of renewables through feed-in tariffs and other measures. That during the next 20 years, wind power will account for more than 20% of global energy production [14]-[16].

Nevertheless, the biggest barriers to the widespread implementation of wind energy (WE) production are the particular conditions required in its manufacturing, namely the advanced and costly methods necessary to create WE and the huge surfaces demanded [17]-[20]. A WE are accessible all year round, in contrast to SE, which is only accessible for certain parts of the year. Numerous companies sell a range of WE model providing modest prices and differing degrees of efficacy. On the other hand, there are complex WE with complex gearshifts that show the constant efforts required to attain perfections in energy gathering efficacy [12],[21][22].

To increase the FRTC, a number of strategies using a range of scientific methods have been proposed in this area [23][24]. They fall into two primary groups: (1) passive (PMs) and (2) active (AMs) approaches, both of which are thoroughly discussed in [25]. Instead of using costly tools of DFIG that was proposed in [26], appropriate converter governs were utilized in AMs to strengthen the FRTC in conjunction with a conventional crowbar circuit. One of PM's disadvantages is that installing more instruments raises expenses. A modified GSC control strategy was used to provide FRTC [27]. Similarly, it has been demonstrated that utilizing only traditional vector control techniques for converter regulation is more effective in meeting the grid code requirements [28]. Although these control techniques are simple, they cannot sustain the FRTC at large voltage sags (VDs) [29]. With the help of clever controllers, regulators were developed to ensure the FRTC during VDs [30], and they outperformed the PI controllers of the past. A linear controller was created to manage the after-fault situation [31]. Nevertheless, due to their numerical and theoretical difficulty, these methods are very challenging to implement in a DFIG system built on two series converters. Improved crowbar systems continue to be the dominant method because of its controllability and convenience of use [32][33]. Therefore, the goal of this effort is to cooperate with the GSA to design a crowbar system. To further demonstrate the efficacy of the suggested approach, three scenarios in four examples are examined.

- METHODS

DFIGs have extra capabilities that allow them to function at speeds that are somewhat faster or slower than their inherent synchronous pace. This is advantageous for large DFIGs since wind speed may vary fast. The blades of a WT want to accelerate when hit by a gust, but because synchronous generators are synced to the speed of the power grid, they are unable to do so. The hub, gearbox, and generator all experience significant stresses when the electrical grid pushes back. The mechanism is harmed and worn down as a result. The strains are reduced and the wind gust's energy is transferred to usable electricity if the turbine is permitted to accelerate right away after being impacted by a gust [34]-[36].

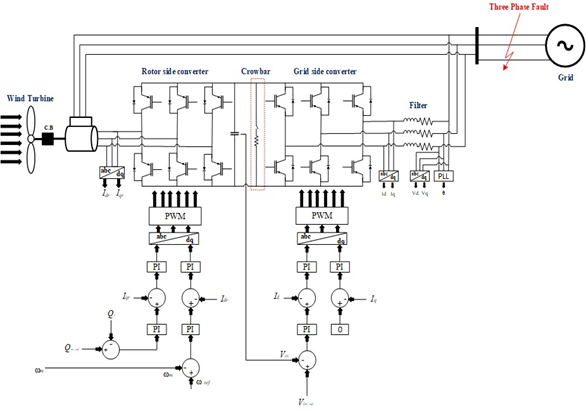

Accepting the frequency that the generator produces, converting it to DC, and then using an inverter to convert it back to AC at the required output frequency is one method for allowing the speed of a WT to vary. This is typical of WTs used on farms and small homes. However, the size and cost of the inverters are needed for megawatt-scale WTs. DFIGs are one approach to this issue. Two stationary and one rotating three-phase windings are independently linked to the generator outside the equipment in place of the typical field winding feds with the DC and winding with the armature where the produced power exits. Hence, "doubly fed". Three-phase AC power is generated at the appropriate grid frequency by one winding, which is directly coupled to the output. The other winding, which is typically Known as the field, although in this instance, both might be outputs, is linked to 3-phase AC electricity with variable frequency. To account for fluctuation in the speed WT this i/p power is phased and frequency-adjusted. A converter from AC /DC /AC is needed for frequency change and phase. This is often built using extremely massive IGBT semiconductors. Because it is bidirectional, the converter may transmit power in either way. Both the output winding and this winding are capable of supplying power can be seen in Figure 1 [37]-[39].

Figure 1. Addressed system

- Power Conversion of DFIG

The rotor windings (RW) have been wired to a power converter, while stator winding (SW) is linked to the grid directly. To produce the stator magnetic field, the grid energizes the SWs. Create the rotor field magnetic, the converter energizes the RWs. The interaction of the stator magnetic fields with the rotor magnetic field produces torque. The two magnetic fields' combined strength and their relative angular displacement determine how much torque is produced. Because the stator is directly related to the grid, its field depends on the grid voltage, and its rotation depends on grid freq. & relates to the synchronous speed. Since the stator flux may be taken into consideration as constant. In steady state operation grid voltage can be considered to be relatively constant, which means the power converter directly manages the rotor flux will rotate. As a result, altering the rotor current's size and angle concerning the stator flux will directly affect how much torque is produced in the DFIG. The applied stator voltage in which magnitude of grid voltage and phase and managing the rotor current such that perpendicular to the stator flux and large enough to provide the necessary torque it is possible to calculate the angular position and stator flux [40]-[42].

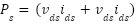

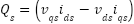

- Operation and control of RSC

Direct control of the rotor current is used to regulate the output torque. The RSC accomplishes this by supplying the rotor windings with a voltage that matches the desired current. The torque, P controllers on the RSC can be used to regulate the DFIG's output P. The torque, speed, or power is often controlled to their reference value using a PI controller. Regardless of the controller employed, its output is the desired rotor current necessary to provide the desired values. The controller output is the rotor voltage reference and the inner control loop of PI is used to bring the error of rotor current from a reference value. The rotor current can also be utilized to regulate the DFIG's ability to produce Q [43]-[45].

- Operation and control of GSC

The DCLV is controlled by the GSC to keep it with accepted limit, GSC on the outer loop controls it. The GSC current is managed by a PI inner control loop. It is typical for the GSC to maximize the output P and set  = 0. Due to the GSC's direct grid connection, it is required to provide power at a constant frequency that matches the grid frequency [46][47].

= 0. Due to the GSC's direct grid connection, it is required to provide power at a constant frequency that matches the grid frequency [46][47].

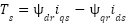

- Mathematical Modelling

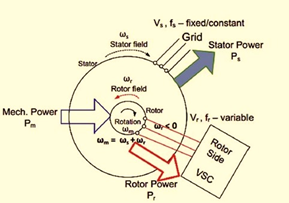

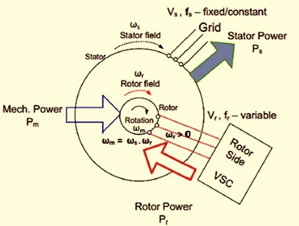

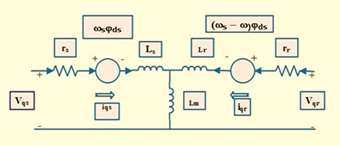

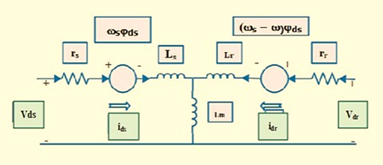

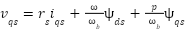

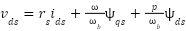

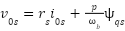

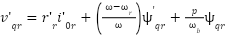

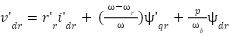

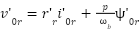

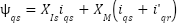

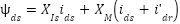

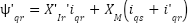

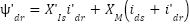

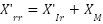

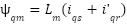

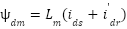

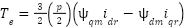

Figure 2(a) and Figure 2(b), shows the DFIG modes (super-synchronous (s is -tve), (b) sub-synchronous (s is +tve)). The DFIG model is presented in Eqs. (1) to Eqs. 21 and fully detailed in [48]-[51]. Figure 3 represents the DFIG circuit.

|

|

(a) | (b) |

Figure 2. DFIG Modes: (a) super-synchronous, (b) sub-synchronous

|

|

(a) | (b) |

Figure 3. (a) d-q frame depicts both the d-q-axis comparable circuit, and (b) control system schematic diagram

|

| (1) |

|

| (2) |

|

| (3) |

|

| (4) |

|

| (5) |

|

| (6) |

|

| (7) |

|

| (8) |

|

| (9) |

|

| (10) |

|

| (11) |

|

| (12) |

|

| (13) |

|

| (14) |

|

| (15) |

|

| (16) |

|

| (17) |

|

| (18) |

|

| (19) |

|

| (20) |

|

| (21) |

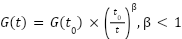

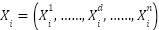

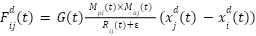

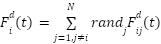

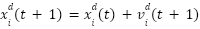

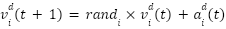

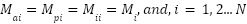

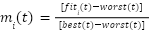

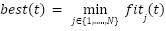

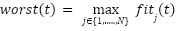

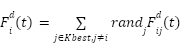

- Investigated optimizer

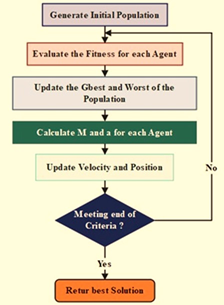

The mathematical model of the GSA is fully described and discussed in [52][53]. The GSA flowchart is presented in Figure 4.

|

| (22) |

|

| (23) |

|

| (24) |

|

| (25) |

|

| (26) |

|

| (27) |

|

| (28) |

|

| (29) |

|

| (30) |

|

| (31) |

|

| (32) |

|

| (33) |

|

| (34) |

|

| (35) |

|

| (36) |

|

| (37) |

|

| (38) |

|

| (39) |

|

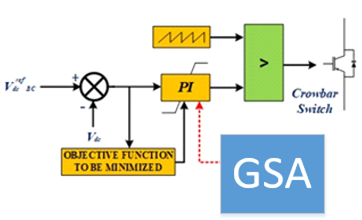

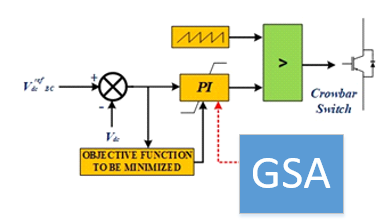

| (40) |

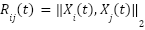

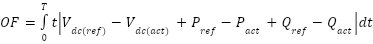

Grid faults have a negative impact on DFIGs' responsiveness. These problems result in amplified DFIG (speeds, DCLV, and currents), torque fluctuations, and a decrease the P [54]-[56]. The DFIG's RSC is safeguarded by a crowbar, which also enhances the responsiveness of the system under grid failures. By using a crowbar, DFIG can sustain energy even in the event of a grid failure and weather the fault. For DFIG, the values of Ki and Kp are 0.05328. The controller's inputs are the values that are being watched and pointed to, and its output decides how to run the system while accounting for the sawtooth signal. Figure 5 shows the suggested crowbar control technique. The crowbar action can often be represented as in (41). The parameters for each of the subsequent equations are explained in detail [57]-[59].

The choosen objective function using the GSA is defined as follows :

|

| (47) |

Figure 4. The GSA flowchart

Figure 5. Proposed strategy

- RESULT AND DISCUSSION

In order to demonstrate the function of the GSA approach, this study discusses the recital enhancement of DFIG under various scenarios. Three scenarios have been used to test different fault conditions (0.0 V, 0.3 V, 0.5 V, and 0.7 V) in order to demonstrate the influence of GSA. The scenarios are (C1) unprotected, (C2) with a traditional crowbar, and (C3) with an improved crowbar. To demonstrate how the suggested technique affects DFIG performance, all of (P, VDC, Q,  ) are examined. To verify the effectiveness of the recommended approach, the analyzed DFIG is simulated using MATLAB/Simulink. The PCC is a crucial location to evaluate FRTC. The parameters of the system are mentioned in [60].

) are examined. To verify the effectiveness of the recommended approach, the analyzed DFIG is simulated using MATLAB/Simulink. The PCC is a crucial location to evaluate FRTC. The parameters of the system are mentioned in [60].

- Case 1: 100% Voltage Dip (VD)

As shown in Figure 6, a fault time of 200 ms is used to assess the effectiveness of the suggested strategy under a 100% VD. Part (a) shows that P declines with a fault, while parts (b), (c), and (d) show that Q,  , and

, and  rise. To maintain

rise. To maintain  as shown in part (c), the crowbar is within the designated range. Overshoot of P and oscillations in

as shown in part (c), the crowbar is within the designated range. Overshoot of P and oscillations in  are muffled. Nevertheless, spite of significant malfunctions, the DFIG manages to function as intended, according to the outcomes. Table 1 summarizes and lists all of the DFIG's fluctuations and alterations for the instances that are being studied.

are muffled. Nevertheless, spite of significant malfunctions, the DFIG manages to function as intended, according to the outcomes. Table 1 summarizes and lists all of the DFIG's fluctuations and alterations for the instances that are being studied.

Figure 6. System outcomes under case 1

- Case 2: 70% VD

The suggested method is tested with a fault period of 200 ms under a 70% VD as depicted in Figure 7. In part (a), P falls at fault, whereas parts (b), (c), and (d) show a rise in Q,  , and

, and  . Part (c) shows the crowbar in order to maintain

. Part (c) shows the crowbar in order to maintain  within the designated range. There is a muffled overrun of P and swings in

within the designated range. There is a muffled overrun of P and swings in  . The findings seen demonstrate that despite significant failures, the DFIG maintains to function as intended. A summary and list of DFIG's fluctuations and changes for the cases under investigation may be seen in Table 1.

. The findings seen demonstrate that despite significant failures, the DFIG maintains to function as intended. A summary and list of DFIG's fluctuations and changes for the cases under investigation may be seen in Table 1.

Figure 7. System outcomes under case 2

- Case 3: 50% VD

For the evaluation of the suggested plan, the failure interval is 200 ms at a 50% VD as in Figure 8. Part (a) shows that P declines during a fault, while parts (b), (c), and (d) show that Q,  , and

, and  rise. As shown in part (c), the crowbar was employed to maintain

rise. As shown in part (c), the crowbar was employed to maintain  within the designated range. The overshoot of P and vibrations in

within the designated range. The overshoot of P and vibrations in  are muffled. The DFIG remains to function as intended, according to the actual simulation outcomes. Table 1 summarizes and lists the variances for the instances that are being studied.

are muffled. The DFIG remains to function as intended, according to the actual simulation outcomes. Table 1 summarizes and lists the variances for the instances that are being studied.

Figure 8. System outcomes under case 3

- Case 4: 30% VD

To verify the suggested arrangement, a 30% VD interval of 200 ms is used as in Figure 9. Part (a) shows that P declines at a malfunction, while parts (b), (c), and (d) show that Q,  , and

, and  rise, respectively. As shown in part (c), the crowbar is used to maintain the

rise, respectively. As shown in part (c), the crowbar is used to maintain the  at the acceptable values. When any changes in

at the acceptable values. When any changes in  and P overshoot were suppressed, the proposed technique performs well. when the FRTC has been attained and a problem has been fixed before Q is pumped. Even in the face of significant errors, the DFIG maintains to function as intended, according to the reported simulated outcomes. Table 1 summarizes and lists the outcomes.

and P overshoot were suppressed, the proposed technique performs well. when the FRTC has been attained and a problem has been fixed before Q is pumped. Even in the face of significant errors, the DFIG maintains to function as intended, according to the reported simulated outcomes. Table 1 summarizes and lists the outcomes.

Figure 9. System outcomes under case 4

Table 1. Performance of DFIG under investigated scenarios

Parameters | 100% VD | 70% VD | 50% VD | 30% VD |

C1 | C2 | C3 | C1 | C2 | C3 | C1 | C2 | C3 | C1 | C2 | C3 |

p | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 3.5 | 2 | 3.5 | 4.8 | 3.5 | 4.8 | 6 | 4.1 | 6 |

Q | 6.1 | 5 | 6.1 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3.5 | 3 | 3.5 | 1.5 | 1 | 1.5 |

| 4490 | 1200 | 1500 | 2500 | 1190 | 1500 | 1200 | 1175 | 1200 | 1200 | 1175 | 1200 |

| 1.15 | 1.27 | 1.15 | 1.148 | 1.25 | 1.148 | 1.14 | 1.24 | 1.14 | 1.13 | 1.23 | 1.13 |

- CONCLUSIONS

The idea presented in this paper concerns the DCLV control of a DFIG, where power converters are costly. It was focused on crowbar control which permits to mitigation of overvoltage at the DCL which could be produced under faults. As given in the introduction section, the structure of the proposed strategy allows us to overcome the weak points of recent methods described previously. This is for the reason that it ensures robustness under the presence of faults as demonstrated through the obtained outcomes. The GSA proves its role in helping the crowbar to operate efficiently. The developed method is based on simple formulas and it was insensitive to sensors’ noises and offsets. Utilizing optimization based on the GSA, the PI controller for a DFIG was optimized. It was discovered that the controller parameters produced using GSA have smaller overshoot, settling time, and rising time. In addition to improving system responses, the GSA-based controller significantly supports the wind system to achieve FRTC.

DECLARATION

Author Contribution

All authors contributed equally to the main contributor to this paper. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- B. N. Iyke, “Climate change, energy security risk, and clean energy investment,” Energy Econ., vol. 129, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2023.107225.

- M. Awad et al., “A review of water electrolysis for green hydrogen generation considering PV/wind/hybrid/hydropower/geothermal/tidal and wave/biogas energy systems, economic analysis, and its application,” Alexandria Eng. J., vol. 87, no. November 2023, pp. 213–239, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2023.12.032.

- F. Menzri et al., “Applications of Novel Combined Controllers for Optimizing Grid-Connected Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems,” Sustain., vol. 16, no. 16, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166825.

- M. Foglia, E. Angelini, and T. L. D. Huynh, “Tail risk connectedness in clean energy and oil financial market,” Ann. Oper. Res., vol. 334, no. 1–3, pp. 575–599, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-022-04745-w.

- M. M. Mahmoud, “Improved current control loops in wind side converter with the support of wild horse optimizer for enhancing the dynamic performance of PMSG-based wind generation system,” Int. J. Model. Simul., vol. 43, no. 6, pp. 952–966, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1080/02286203.2022.2139128.

- H. Boudjemai et al., “Application of a Novel Synergetic Control for Optimal Power Extraction of a Small-Scale Wind Generation System with Variable Loads and Wind Speeds,” Symmetry (Basel)., vol. 15, no. 2, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/sym15020369.

- T. Boutabba, I. Benlaloui, F. Mechnane, I. M. Elzein, M. Ammar, and M. M. Mahmoud, “Design of a Small Wind Turbine Emulator for Testing Power Converters Using dSPACE 1104,” Int. J. Robot. Control Syst., vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 698–712, 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.31763/ijrcs.v5i2.1685.

- P. Casati, M. Moner-Girona, S. I. Khaleel, S. Szabo, and G. Nhamo, “Clean energy access as an enabler for social development: A multidimensional analysis for Sub-Saharan Africa,” Energy Sustain. Dev., vol. 72, pp. 114–126, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2022.12.003.

- M. M. Mahmoud et al., “Application of Whale Optimization Algorithm Based FOPI Controllers for STATCOM and UPQC to Mitigate Harmonics and Voltage Instability in Modern Distribution Power Grids,” Axioms, vol. 12, no. 5, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms12050420.

- N. F. Ibrahim et al., “A new adaptive MPPT technique using an improved INC algorithm supported by fuzzy self-tuning controller for a grid-linked photovoltaic system,” PLoS One, vol. 18, no. 11 November, pp. 1–22, 2023 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293613.

- A. G. Abdullah, D. L. Hakim, N. T. Sugito, and D. Zakaria, “Investigating Evolutionary Trends of Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems: A Bibliometric Analysis from 2004 to 2021,” Int. J. Renew. Energy Res., vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 376–391, 2023, https://doi.org/10.20508/ijrer.v13i1.13766.g8690.

- N. F. Ibrahim et al., “Operation of Grid-Connected PV System with ANN-Based MPPT and an Optimized LCL Filter Using GRG Algorithm for Enhanced Power Quality,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 106859–106876, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3317980.

- E. T. Sayed et al., “Renewable Energy and Energy Storage Systems,” Energies, vol. 16, no. 3. 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/en16031415.

- I. El Maysse et al., “Nonlinear Observer-Based Controller Design for VSC-Based HVDC Transmission Systems Under Uncertainties,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, no. November, pp. 124014–124030, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3330440.

- P. Balakumar, T. Vinopraba, and K. Chandrasekaran, “Deep learning based real time Demand Side Management controller for smart building integrated with renewable energy and Energy Storage System,” J. Energy Storage, vol. 58, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2022.106412.

- S. Heroual, B. Belabbas, and N. B. Elzein I M, Yasser Diab, Alfian Ma’arif, Mohamed Metwally Mahmoud, Tayeb Allaoui, “Enhancement of Transient Stability and Power Quality in Grid- Connected PV Systems Using SMES,” Int. J. Robot. Control Syst., vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 990–1005, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1155/etep/9958218.

- A. Ali et al., “Advancements in piezoelectric wind energy harvesting: A review,” Results in Engineering, vol. 21. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.101777.

- M. M. Mahmoud et al., “Evaluation and Comparison of Different Methods for Improving Fault Ride-Through Capability in Grid-Tied Permanent Magnet Synchronous Wind Generators,” International Transactions on Electrical Energy Systems, vol. 2023. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/7717070.

- O. M. Kamel, A. A. Z. Diab, M. M. Mahmoud, A. S. Al-Sumaiti, and H. M. Sultan, “Performance Enhancement of an Islanded Microgrid with the Support of Electrical Vehicle and STATCOM Systems,” Energies, vol. 16, no. 4, 2023, doi: 10.3390/en16041577.

- [20] P. Sinha et al., “Efficient automated detection of power quality disturbances using nonsubsampled contourlet transform & PCA-SVM,” Energy Explor. Exploit., vol. 00, no. 00, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1177/01445987241312755.

- N. F. Ibrahim et al., “Multiport Converter Utility Interface with a High-Frequency Link for Interfacing Clean Energy Sources (PV\Wind\Fuel Cell) and Battery to the Power System: Application of the HHA Algorithm,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 18, p. 13716, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813716.

- Y. Maamar, I. M. Elzein, H. Alnami, B. Brahim, and M. M. M. Benameur, Afif Benameur, Horch Mohamede, “Design, Modeling, and Simulation of A New Adaptive Backstepping Controller for Permanent Magnet Linear Synchronous Motor: A Comparative Analysis,” Int. J. Robot. Control Syst., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 296–310, 2025, https://doi.org/10.31763/ijrcs.v5i1.1425.

- H. P. Dang and H. N. Villegas Pico, “Blackstart and Fault Ride-Through Capability of DFIG-Based Wind Turbines,” IEEE Trans. Smart Grid, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 2060–2074, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/TSG.2022.3214384.

- F. Bouaziz, A. Masmoudi, A. Abdelkafi, and L. Krichen, “Coordinated Control of SMES and DVR for Improving Fault Ride-Through Capability of DFIG-based Wind Turbine,” Int. J. Renew. Energy Res., vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 359–371, 2022, https://doi.org/10.20508/ijrer.v12i1.12681.g8410.

- S. R. Mosayyebi, S. H. Shahalami, and H. Mojallali, “Fault ride-through capability improvement in a DFIG-based wind turbine using modified ADRC,” Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst., vol. 7, no. 1, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1186/s41601-022-00272-9.

- M. I. Mosaad, A. Abu-Siada, M. M. Ismaiel, H. Albalawi, and A. Fahmy, “Enhancing the fault ride-through capability of a DFIG-WECS using a high-temperature superconducting coil,” Energies, vol. 14, no. 19, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/en14196319.

- M. K. Döşoğlu, “Nonlinear dynamic modeling for fault ride-through capability of DFIG-based wind farm,” Nonlinear Dyn., vol. 89, no. 4, pp. 2683–2694, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-017-3617-8.

- M. R. Islam, J. Hasan, M. R. R. Shipon, M. A. H. Sadi, A. Abuhussein, and T. K. Roy, “Neuro Fuzzy Logic Controlled Parallel Resonance Type Fault Current Limiter to Improve the Fault Ride through Capability of DFIG Based Wind Farm,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 115314–115334, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3000462.

- P. M. Tripathi and K. Chatterjee, “Real-time implementation of ring based saturated core fault current limiter to improve fault ride through capability of DFIG system,” Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst., vol. 131, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2021.107040.

- M. A. Hossain, M. R. Islam, M. Y. Y. U. Haque, J. Hasan, T. K. Roy, and M. A. H. Sadi, “Protecting DFIG-based multi-machine power system under transient-state by nonlinear adaptive backstepping controller-based capacitive BFCL,” IET Gener. Transm. Distrib., vol. 16, no. 22, pp. 4528–4548, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1049/gtd2.12617.

- P. Verma, S. Kaimal, and B. Dwivedi, “Enhancement in fault ride through capabilities with inertia control for DFIG-wind energy conversion system,” Int. J. Ambient Energy, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 6175–6187, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1080/01430750.2021.2000890.

- E. Bekiroglu and M. D. Yazar, “Improving Fault Ride Through Capability of DFIG with Fuzzy Logic Controlled Crowbar Protection,” in 11th IEEE International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications, ICRERA 2022, pp. 374–378. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRERA55966.2022.9922804.

- M. M. Mahmoud, B. S. Atia, A. Y. Abdelaziz, and N. A. N. Aldin, “Dynamic Performance Assessment of PMSG and DFIG-Based WECS with the Support of Manta Ray Foraging Optimizer Considering MPPT, Pitch Control, and FRT Capability Issues,” Processes, vol. 10, no. 12, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/pr10122723.

- H. Alnami, S. A. E. M. Ardjoun, and M. M. Mahmoud, “Design, implementation, and experimental validation of a new low-cost sensorless wind turbine emulator: Applications for small-scale turbines,” Wind Eng., vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 565–579, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1177/0309524X231225776.

- M. B. Tuka and S. M. Endale, “Analysis of Doubly Fed Induction Generator-based wind turbine system for fault ride through capability investigations,” Wind Eng., vol. 47, no. 6, pp. 1132–1150, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1177/0309524X231186762.

- H. Boudjemai et al., “Experimental Analysis of a New Low Power Wind Turbine Emulator Using a DC Machine and Advanced Method for Maximum Wind Power Capture,” IEEE Access, vol. PP, p. 1, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3308040.

- L. Simon, J. Ravishankar, and K. S. Swarup, “Coordinated reactive power and crow bar control for DFIG-based wind turbines for power oscillation damping,” Wind Eng., vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 95–113, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1177/0309524X18780385.

- A. Dendouga, A. Dendouga, and N. Essounbouli, “High performance of variable-pitch wind system based on a direct matrix converter-fed DFIG using third order sliding mode control,” Wind Eng., vol. 48, no. 3, pp. 325–348, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1177/0309524X231199435.

- O. M. Lamine et al., “A Combination of INC and Fuzzy Logic-Based Variable Step Size for Enhancing MPPT of PV Systems,” Int. J. Robot. Control Syst., vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 877–892, 2024, doi: 10.31763/ijrcs.v4i2.1428 https://doi.org/10.31763/ijrcs.v4i2.1428.

- C. Du, X. Du, and C. Tong, “SSR Stable Wind Speed Range Quantification for DFIG-Based Wind Power Conversion System Considering Frequency Coupling,” IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 125–139, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/TSTE.2022.3203317.

- I. R. de Oliveira, F. L. Tofoli, and V. F. Mendes, “Thermal Analysis of Power Converters for DFIG-Based Wind Energy Conversion Systems during Voltage Sags,” Energies, vol. 15, no. 9, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/en15093152.

- M. N. A. Hamid et al., “Adaptive Frequency Control of an Isolated Microgrids Implementing Different Recent Optimization Techniques,” Int. J. Robot. Control Syst., vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 1000–1012, 2024, https://doi.org/10.31763/ijrcs.v4i3.1432.

- Z. Xie, M. Li, S. Yang, and X. Zhang, “Stability analysis of DFIG controlled by hybrid synchronization mode and its improved control strategy under weak grid,” IET Renew. Power Gener., vol. 17, no. 8, pp. 1940–1951, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1049/rpg2.12740.

- H. Boudjemai et al., “Design, Simulation, and Experimental Validation of a New Fuzzy Logic-Based Maximal Power Point Tracking Strategy for Low Power Wind Turbines,” Int. J. Fuzzy Syst., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 296–310, 2025, https://doi.org/10.31763/ijrcs.v5i1.1425.

- B. Krishna Ponukumati et al., “Evolving fault diagnosis scheme for unbalanced distribution network using fast normalized cross-correlation technique,” PLoS One, vol. 19, no. 10, pp. 1–23, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305407.

- X. Gao, Z. Wang, L. Ding, W. Bao, Z. Wang, and Q. Hao, “A novel virtual synchronous generator control scheme of DFIG-based wind turbine generators based on the rotor current-induced electromotive force,” Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst., vol. 156, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2023.109688.

- A. T. Hassan et al., “Adaptive Load Frequency Control in Microgrids Considering PV Sources and EVs Impacts: Applications of Hybrid Sine Cosine Optimizer and Balloon Effect Identifier Algorithms,” Int. J. Robot. Control Syst., vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 941–957, 2024, https://doi.org/10.31763/ijrcs.v4i2.1448.

- J. Liu, C. Wang, J. Zhao, B. Tan, and T. Bi, “Simplified Transient Model of DFIG Wind Turbine for COI Frequency Dynamics and Frequency Spatial Variation Analysis,” IEEE Trans. Power Syst., vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 3752–3768, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2023.3301928.

- R. Gianto, Purwoharjono, F. Imansyah, R. Kurnianto, and Danial, “Steady-State Load Flow Model of DFIG Wind Turbine Based on Generator Power Loss Calculation,” Energies, vol. 16, no. 9, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/en16093640.

- U. Buragohain and N. Senroy, “Reduced Order DFIG Models for PLL-Based Grid Synchronization Stability Assessment,” IEEE Trans. Power Syst., vol. 38, no. 5, pp. 4628–4639, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2022.3215125.

- D. Assessment and C. Defect, “Dynamic Assessment and Control of a Dual Star Induction Machine State Dedicated to an Electric Vehicle Under Short- Circuit Defect,” Int. J. Robot. Control Syst., vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 1731–1745, 2024, https://doi.org/10.31763/ijrcs.v4i4.1557.

- R. García-Ródenas, L. J. Linares, and J. A. López-Gómez, “Memetic algorithms for training feedforward neural networks: an approach based on gravitational search algorithm,” Neural Comput. Appl., vol. 33, no. 7, pp. 2561–2588, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-020-05131-y.

- N. M. Sabri, U. F. M. Bahrin, and M. Puteh, “Enhanced Gravitational Search Algorithm Based on Improved Convergence Strategy,” Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl., vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 661–670, 2023, https://doi.org/10.14569/IJACSA.2023.0140670.

- O. P. Mahela, N. Gupta, M. Khosravy, and N. Patel, “Comprehensive overview of low voltage ride through methods of grid integrated wind generator,” IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 99299–99326, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2930413.

- R. Hiremath and T. Moger, “Comprehensive review on low voltage ride through capability of wind turbine generators,” Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst., vol. 30, no. 10, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1002/2050-7038.12524.

- L. Yuan, K. Meng, J. Huang, Z. Yang Dong, W. Zhang, and X. Xie, “Development of HVRT and LVRT control strategy for pmsg-based wind turbine generators y,” Energies, vol. 13, no. 20, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/en13205442.

- A. M. A. Haidar, K. M. Muttaqi, and M. T. Hagh, “A coordinated control approach for DC link and rotor crowbars to improve fault ride-through of dfig-based wind turbine,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl., vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 4073–4086, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1109/TIA.2017.2686341.

- Y. Ling, “A fault ride through scheme for doubly fed induction generator wind turbine,” Aust. J. Electr. Electron. Eng., vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 71–79, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1080/1448837X.2018.1525172.

- J. Yin, X. Huang, and W. Qian, “Analysis and research on short-circuit current characteristics and grid access faults of wind farms with multi-type fans,” Energy Reports, vol. 11, pp. 1161–1170, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2023.12.046.

- S. Swain and P. K. Ray, “Short circuit fault analysis in a grid connected DFIG based wind energy system with active crowbar protection circuit for ridethrough capability and power quality improvement,” Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst., vol. 84, pp. 64–75, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2016.05.006.

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

| Amany Fayz Ali Ahmed is a researcher who specializes in Renewable Energy Power Systems and Control Systems. She is master’s student at Electrical Engineering Department, Faculty of Energy Engineering, Aswan University. |

|

|

| I. M. Elzein is an electrical and electronics engineer who pursued his undergraduate and graduate level degrees in Electrical and computer engineering from Wayne State University, Michigan, USA in 2004. Currently, Dr. Elzein is holding an academic lecturing role in the department of telecommunication and networking engineering at the University of Doha for Science and Technology. Dr. Elzein has more than 70 research papers in Mult international conferences and journals as well being a reviewer committee member and technical program committee. His research profile is mainly in the fields of electrical and electronic engineering with a concentration on (PV) photovoltaic systems. |

|

|

| Mohamed Metwally Mahmoud received the B.Sc., M.Sc., and Ph.D. degrees in electrical engineering from Aswan University, Egypt, in 2015, 2019, and 2022, respectively. He is currently a Professor (Assistant) at Aswan University. His research interests include optimization methods, intelligent controllers, fault ride-through capability, and power quality. He has been awarded Aswan University prizes for international publishing~2024. He is the author or coauthor of many refereed journals and conference papers. He reviews for some well-known publishers (IEEE, Springer, Wiley, Elsevier, Taylor & Francis, and Sage). |

|

|

| Sid Ahmed El Mehdi Ardjoun is a professor and researcher at the University of Sidi-Bel-Abbès and the IRECOM laboratory in Algeria. His research focuses on robust, intelligent, and fault-tolerant control of electrical systems, with applications in renewable energy and electric drives. He aims to optimize both the dynamic and static performance of electrical systems while enhancing their quality and energy efficiency. |

|

|

| Ahmed M. Ewais (Member, IEEE) received the B.S. and M.Sc. degrees in power and electrical engineering from the Faculty of Energy Engineering, Aswan University, Aswan, Egypt, in 1999 and 2005, respectively, and the Ph.D. degree from the Cardiff School of Engineering, Cardiff University, U.K., in 2014. He is currently an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Energy Engineering, at Aswan University. His main research interests include power system stability, control, renewable power generation and its integration, electrical machine design, and load frequency control. |

|

|

| Usama Khaled received the M.Sc. degree in electrical engineering from Aswan University, Egypt, in 1998 and 2003, respectively, and the joint Ph.D. degree in electrical engineering from Cairo University, Egypt, and Kyushu University, Japan, through a Joint Scholarship, in 2010. Since 2000, he has been with the Department of Electrical Power Engineering, Faculty of Energy Engineering, Aswan University, Egypt. His research interests include nano-dielectric materials, applied electrostatics, renewable energy, and high-voltage technologies. He has been an Assistant Professor and an Associate Professor at the College of Engineering, King Saud University, since 2014 and 2018, respectively. He is currently a Professor and the Head of the Electrical Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Aswan University. |

Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, Vol. 7, No. 2, June 2025, pp. 122-137