Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro ISSN: 2685-9572

DNA-based Cryptography for Internet of Things Security: Concepts, Methods, Applications, and Emerging Trends

Mircea Ţălu 1,2

1 Faculty of Automation and Computer Science, The Technical University of Cluj-Napoca, 26-28 George Barițiu St., Cluj-Napoca, 400027, Cluj county, Romania

2 SC ACCESA IT SYSTEMS SRL, Constanța St., no. 12, Platinia, CP. 400158, Cluj-Napoca, Romania

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 21 February 2025 Revised 14 April 2025 Published 19 April 2025 |

|

DNA-based cryptography is an emerging field that combines molecular biology and computational security to develop novel encryption, secure data storage, and steganographic techniques. It offers a promising alternative to traditional cryptographic systems, addressing challenges like storage efficiency, robustness, and resistance to computational attacks. In the era of the Internet of Things (IoT), where massive networks of interconnected devices continuously generate and exchange sensitive data, ensuring secure communication and storage has become a critical challenge. DNA-based cryptography presents a unique opportunity to enhance IoT security by offering ultra-secure encryption methods that exploit DNA’s vast information density and inherent randomness. These encryption methods leverage the complexity of DNA encoding - such as nucleotide substitution, DNA strand pairing, and biological operations like splicing and amplification - to create security layers that are difficult to decipher using conventional computational techniques. Recent advancements in DNA synthesis, sequencing, and encoding methodologies have facilitated the development of encryption schemes tailored for IoT applications, enabling lightweight, high-capacity security solutions that outperform traditional cryptographic methods. Beyond IoT, DNA-based cryptography also holds potential in areas such as secure biomedical data storage, digital rights management, and archival of sensitive governmental or historical information, demonstrating its broader applicability across diverse domains. Future research should optimize DNA encoding, improve storage technologies, and harness artificial intelligence for real-time threat detection, automated encryption, and adaptive security in IoT systems. This review analyzes DNA-based cryptographic methods, including natural and pseudo-DNA encryption, DNA-based steganography, and hybrid models, while uniquely exploring their IoT applications, emerging trends, practical implementations, key advantages, challenges, and future research directions. |

Keywords: DNA-based Cryptography; DNA-based Cryptographic Methods; DNA-based Security; Internet of Things (IoT); IoT Device Security |

Corresponding Author: Mircea Ţălu, Faculty of Automation and Computer Science, The Technical University of Cluj-Napoca, 26-28 George Barițiu St., Cluj-Napoca, 400027, Cluj county, Romania. Email: talu.s.mircea@gmail.com |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: Mircea Ţălu, “DNA-based Cryptography for Internet of Things Security: Concepts, Methods, Applications, and Emerging Trends,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 68-94, 2025, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v7i2.12942. |

- INTRODUCTION

The escalating frequency and sophistication of cyber threats have made cybersecurity a critical global concern for individuals, organizations, and governments [1]-[3]. As digital infrastructures become increasingly interconnected, ensuring the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of sensitive information has become a paramount priority. The widespread adoption of the Internet, social media platforms, cloud storage solutions, and advanced networking technologies has introduced a multitude of cybersecurity challenges, necessitating the development of sophisticated protective measures. These challenges are further exacerbated by the growing complexity and frequency of cyber threats, including denial-of-service (DoS) attacks, malware propagation, ransomware incursions, and phishing schemes, all of which have significant implications for global security [4]-[6]. The ramifications of these digital threats are profound, leading to extensive data breaches, substantial financial losses, compromised personal privacy, and reputational damage across sectors [7]-[9].

To counteract the growing complexity of cyber threats, numerous solutions have been proposed, encompassing a combination of advanced technologies and strategic processes designed to mitigate unauthorized access and potential harm to critical systems and digital assets [10]-[13]. Traditional security mechanisms, such as firewalls, intrusion detection systems, and encryption protocols, have played a crucial role in safeguarding digital information. However, as these threats evolve, conventional cryptographic techniques are facing significant limitations [14]-[18].

With the emergence of quantum computing, previously robust encryption algorithms such as Rivest-Shamir-Adleman (RSA), Advanced Encryption Standard (AES), and Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) are now at risk of being rendered obsolete due to their vulnerability to quantum-based decryption methods [19]-[21]. This has created an urgent demand for the development of more resilient, quantum-resistant cryptographic solutions capable of addressing contemporary cybersecurity challenges [22]-[24]. Experts predict that quantum computers capable of breaking these encryption techniques could become a reality within the next 10-20 years, creating an urgent demand for more resilient, quantum-resistant cryptographic solutions. Simultaneously, the rapid proliferation of the Internet of Things (IoT) has transformed industries by enabling seamless data exchange and real-time communication across a wide range of applications, including smart cities, healthcare monitoring, industrial automation, intelligent transportation systems, and university education, where IoT facilitates smart classrooms, remote learning, and advanced research infrastructure [25]-[27].

While IoT technologies offer numerous advantages in terms of efficiency and automation, they also introduce a new dimension of security vulnerabilities [28]. IoT networks, often composed of resource-constrained devices with limited computational power and energy reserves, are particularly susceptible to cyber threats such as unauthorized access, data interception, and system manipulation [29]. Conventional encryption techniques, despite their proven effectiveness, impose significant computational overhead on IoT devices, thereby limiting their practical applicability in real-world deployments [30]-[32]. However, IoT networks are increasingly targeted by cyberattacks. For example, the 2016 Mirai botnet attack exploited vulnerabilities in unsecured IoT devices to launch one of the largest distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks in history, highlighting the significant security risks posed by weak authentication and outdated software in IoT devices.

To address these pressing security concerns, DNA-based cryptography has emerged as a novel and bio-inspired encryption paradigm that leverages the inherent properties of DNA sequences for secure communication and data protection [33]-[35].

DNA-based cryptographic methods exploit the vast information storage capacity, randomness, and biochemical uniqueness of DNA molecules to enhance encryption, key management, and authentication mechanisms. By integrating principles from molecular biology with computational security frameworks, DNA-based cryptography offers a promising approach to fortifying IoT security. Recent advancements in DNA synthesis, sequencing, and encoding techniques have facilitated the development of innovative cryptographic models that provide robust protection against conventional and quantum-based cyber threats while maintaining computational efficiency [36]-[38].

With the growing adoption of IoT technologies across a wide range of sectors, the incorporation of DNA-based cryptographic methodologies offers a promising strategy for enhancing the security, scalability, and resilience of IoT infrastructures [39]-[41]. This integration has the potential to address key vulnerabilities in current security paradigms by providing advanced cryptographic solutions that leverage the unique properties of DNA, such as its high information density and molecular-level security. As IoT networks expand and become increasingly interconnected, DNA-based cryptography could offer a future-proof solution capable of safeguarding sensitive data and ensuring robust protection against emerging cyber threats, both conventional and quantum-based.

This paper provides a comprehensive review of DNA-based cryptographic techniques, emphasizing their potential to revolutionize IoT security by addressing both conventional and quantum cyber threats. It also offers a thorough analysis of these methods, exploring their applications in IoT security, highlighting key benefits and challenges, and outlining future research directions to optimize their practical implementation.

- RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

A systematic review was undertaken to critically evaluate the advancements, limitations, and emerging research directions in DNA-based cryptographic methodologies, with a particular emphasis on their applicability in IoT security and the broader IoT ecosystem. The study aimed to consolidate fundamental principles, assess cryptographic security mechanisms, and propose pathways for future innovation in bio-inspired encryption. The methodological framework was structured into the following stages:

- Formulation of research questions – Defining core inquiries pertaining to DNA cryptography's theoretical underpinnings, implementation strategies, and security efficacy within IoT security frameworks.

- Comprehensive literature acquisition – Conducting an exhaustive search across multiple high-impact academic repositories to identify relevant studies linking DNA-based cryptography and IoT security.

- Rigorous study evaluation – Assessing methodological robustness, computational feasibility, and cryptographic applicability, particularly in resource-constrained IoT environments.

- Evidence synthesis and thematic categorization – Identifying key trends, algorithmic advancements, and potential IoT security applications.

- Critical analysis and gap identification – Evaluating inconsistencies, computational constraints, and unexplored research avenues in DNA-based cryptography for IoT security.

The review encompassed literature from 2000 to 2025, with a particular emphasis on peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, and empirical studies focusing on the evolution of DNA-based cryptography frameworks, encoding mechanisms, computational security paradigms, and their intersection with IoT security challenges. In addition to peer-reviewed articles, the review also considered relevant non-peer-reviewed sources, such as preprints and industry reports, to ensure a comprehensive overview of the topic. All sources were carefully assessed for credibility and relevance.

- Literature Search Strategy

To construct a comprehensive and methodologically rigorous foundation, the review sourced literature from globally recognized academic databases, including Scopus, Web of Science, IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, SpringerLink, MDPI, Google Scholar, ACM Digital Library, and PubMed. A structured keyword search strategy was employed to encompass a broad spectrum of DNA-based cryptographic techniques and IoT security considerations, incorporating terms such as: "DNA digital coding techniques", "DNA-inspired cryptographic frameworks", "Natural DNA cryptography", "Pseudo-DNA cryptography", "DNA-based steganography", and "IoT security encryption". To ensure scientific rigor and methodological reliability, inclusion and exclusion criteria were meticulously defined.

- Inclusion criteria: Studies were required to present experimental findings, algorithmic simulations, or validated theoretical models that directly contributed to advancements in DNA-based encryption and its integration with IoT security. Only peer-reviewed journal articles and high-quality conference papers were considered, ensuring that all selected studies demonstrated clear empirical or computational evidence supporting DNA cryptographic methodologies within the context of IoT security.

- Exclusion criteria: Studies that lacked empirical validation, were published in non-English languages, or primarily focused on conceptual frameworks without implementation or security analysis were excluded. Additionally, articles that did not explicitly address DNA-based cryptographic mechanisms or their relevance to IoT security - such as general computational security studies without bio-inspired components - were omitted.

To maximize literature coverage and mitigate selection bias, a citation chaining approach was employed, incorporating both backward and forward citation tracking. This involved analyzing references cited within selected studies while simultaneously identifying more recent publications that cited them. This iterative refinement process ensured a robust and up-to-date selection of scholarly works, facilitating a comprehensive exploration of DNA cryptography's theoretical evolution, practical implementation, and role in securing IoT systems.

- Thematic Analysis and Data Synthesis

- DNA-based encryption models – Examining substitution, transposition, and hybrid encryption techniques and their applicability in IoT security.

- Key generation and management – Assessing entropy-based DNA key structures, randomness properties, and their role in secure IoT device authentication.

- Encoding and decoding mechanisms – Evaluating computational complexity, efficiency, and feasibility in IoT network security.

- Security robustness and attack resistance – Investigating DNA cryptography’s resilience against brute-force attacks, quantum threats, and IoT-specific cyber vulnerabilities.

To ensure methodological transparency and analytical rigor, the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework was adopted for: 1) Article selection and filtering; 2) Data extraction and methodological assessment; 3) Findings synthesis and research gap identification within the domain of IoT security.

Each study was critically evaluated based on quantitative and qualitative performance metrics, including: a) Algorithmic efficiency – Evaluating computational complexity, execution time, and scalability, particularly for IoT applications; b) Cryptographic strength – Assessing resilience against known security threats in IoT environments; c) Feasibility in practical implementation – Analyzing real-world applicability and system integration potential within IoT security frameworks.

Studies that failed to meet methodological rigor or lacked substantial empirical validation were excluded to maintain high evidentiary standards

- Validation and Reliability Measures

To enhance the reliability, consistency, and objectivity of the synthesis process, multiple verification techniques were implemented:

- Inter-coder agreement in thematic analysis. Two independent researchers conducted qualitative coding to minimize bias. Cohen’s Kappa coefficient was used to measure coding agreement, with an acceptable threshold of 0.80 ensuring reliability. Any disagreements in thematic categorization were resolved through consensus-based discussions between the two researchers. In cases where consensus could not be reached, a third researcher was consulted to provide a final decision, ensuring objectivity and consistency.

- Cross-verification of synthesized results. Another researcher independently reviewed the synthesized findings to validate thematic coherence and data consistency. This process ensured that the extracted conclusions accurately reflected the original studies and aligned with the overarching research questions concerning IoT security.

- Triangulation of data sources and methodologies. Findings were cross-validated across multiple sources, cryptographic frameworks, and computational models. This methodological triangulation reinforced the robustness and generalizability of the study's conclusions, ensuring that insights were well-supported by diverse and independent lines of evidence, particularly within the IoT security landscape.

2.4. Challenges and methodological considerations

Despite the structured approach, certain methodological challenges were identified:

- Potential publication bias – The likelihood that studies reporting successful DNA encryption techniques were more frequently published. To mitigate this, the review incorporated diverse sources and applied strict quality selection criteria.

- Heterogeneity in methodologies – Variations in computational models and cryptographic implementations posed challenges in direct comparison. This was addressed through categorization into thematic clusters, allowing for structured synthesis, particularly within the IoT security context.

- Evolving nature of DNA-based cryptography – Given the rapid advancements in bio-computing, cryptographic frameworks, and IoT security measures, newly emerging studies may supersede certain findings. To maintain contemporary relevance, only research within the last decade was prioritized, ensuring that the study remains aligned with the latest IoT security innovations. Increasing the emphasis on empirical validation and real-world case studies enhanced the reliability of findings and ensured that proposed solutions are not only theoretically sound but also practically viable in diverse IoT security contexts.

This structured research methodology provides a rigorous, evidence-based framework for analyzing DNA cryptography's role in securing IoT environments, highlighting its potential to enhance security, scalability, and resilience in next-generation connected systems.

- CRYPTOGRAPHY

Cryptography is a specialized field of study and practice focused on the development and application of various techniques designed to ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and authenticity of data. Its primary objective is to safeguard sensitive information from unauthorized access, disclosure, and tampering. As technology has advanced, cryptography has significantly evolved from its early forms - such as simple substitution ciphers - to highly sophisticated, efficient, and secure public-key systems.

Over time, cryptography has become increasingly integral to the security and privacy of communication in the digital era, where data protection is a paramount concern [42]-[44]. The core principle of cryptography rests on two key security strategies: encryption and hiding [17]. Both strategies play distinct but complementary roles in securing data, with encryption being one of the most widely adopted methods for protecting information. Encryption involves the process of transforming readable, original information - referred to as plaintext - into an unreadable, distorted form known as ciphertext. This transformation is achieved through the use of cryptographic algorithms and secret keys.

The cryptographic algorithms are carefully designed mathematical procedures, while the secret keys serve as a critical piece of information that determines the specific transformation. In this manner, encryption ensures the confidentiality of information, preventing unauthorized parties from accessing or interpreting the data. Importantly, only individuals or entities possessing the correct decryption key can reverse the encryption process and recover the original plaintext [42]-[44].

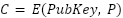

In earlier encryption models, the relationship between plaintext (unencrypted data) and ciphertext (encrypted data) is defined by the following equations [45]:

|

| (1) |

|

| (2) |

where: P represents the plaintext, C the ciphertext, E the encryption algorithm, D the decryption algorithm, and k the cryptographic key.

The encryption and decryption processes are executed using cryptographic keys of fixed size. The cryptographic mechanisms can be categorized into two primary types based on the number of keys utilized: symmetric cryptography and asymmetric cryptography.

In symmetric cryptography, a single key is employed for both encryption and decryption. This key must remain confidential and be securely transmitted over a trusted communication channel to prevent unauthorized access. Since the same key is used for both operations, ensuring its secrecy is critical to maintaining the security of the encrypted data.

Conversely, asymmetric cryptography, also referred to as public-key cryptography, utilizes a pair of mathematically related but distinct keys: a public key and a private key. The public key is accessible to anyone and is typically distributed through a publicly available medium. However, the private key must remain confidential and should not be shared with any party. Importantly, the private key cannot be feasibly derived from the corresponding public key due to the underlying cryptographic principles. This key pair is generated in such a way that data encrypted with the public key can only be decrypted using the corresponding private key, and vice versa.

Mathematically, given a plaintext message P, the encryption process produces the corresponding ciphertext C as follows [45]:

|

| (3) |

where E represents the encryption function, and PubKey denotes the public key.

To recover the original plaintext P, the decryption function is applied using the private key PrivKey, as expressed in the following equation [45]:

|

| (4) |

where D represents the decryption function.

The cryptographic security of asymmetric encryption relies on the computational difficulty of deriving the private key from the public key, which is typically based on complex mathematical problems such as integer factorization, discrete logarithms, or elliptic curve relationships. This fundamental property ensures the robustness and widespread applicability of asymmetric cryptographic systems in secure communications, digital signatures, and key exchange protocols.

In addition to traditional cryptographic methods, the field of DNA-based cryptography represents an innovative extension of conventional cryptography into the realm of life sciences. This emerging subfield explores the unique biological properties of DNA molecules and harnesses their capabilities to develop new, highly secure mechanisms for information encryption [46].

In response to this growing need for innovation in data protection, DNA encoding schemes have emerged as a promising and transformative approach in the field of cybersecurity [47]-[50]. The concept of using DNA as a medium for data encryption and transmission may seem unconventional, yet it harnesses the unique biological properties of Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA), which are particularly well-suited for the modern challenges of digital security [47][48].

DNA, as the fundamental molecule responsible for storing and transmitting genetic information in all living organisms, possesses several key characteristics that make it an attractive option for data storage and encryption [49]. Notably, DNA has an extraordinary storage capacity - just one ounce of DNA, the size of a penny, can store up to 30,000 terabytes of information for over a million years [51][52]. Furthermore, DNA exhibits an inherent capacity for self-replication and evolutionary adaptation without external intervention, making it a highly sustainable and exceptionally robust medium for digital data storage and transmission [49]. The ability of DNA to store vast amounts of information in a compact space, coupled with its resistance to environmental degradation, makes it an ideal medium for encryption and secure data transmission [49]. The unique advantages of DNA computing provide a strong foundation for the advancement of DNA-based cryptographic methodologies. DNA computing, first introduced by L.M. Adleman in 1994, demonstrated the potential of DNA molecules for solving computational problems through molecular operations [53]. Since this pioneering work, the field has evolved to encompass DNA cryptography, which leverages the unique chemical properties of DNA for encryption, decryption, and secure data transmission [49]. The foundational exploration of the intersection between DNA and secure communication was conducted by Clelland et al. [54] in 1999, when they introduced a pioneering steganographic approach that enabled the concealment of secret messages within DNA sequences. Building upon this foundational work, subsequent researchers have developed a range of innovative techniques aimed at utilizing DNA for secure information storage and transmission, thereby contributing to the expansion of cryptographic frameworks. The ongoing interest in DNA-based cryptography is driven by its potential to revolutionize data protection strategies, offering novel solutions to address the increasing demand for secure communication in the digital era [54].

The first and most biologically grounded approach, natural DNA cryptography, involves the direct application of cryptographic algorithms to DNA strands, either in their naturally occurring form or as synthetically generated sequences. This technique typically employs a wet database, which consists of a solution of DNA strands in a test tube, to facilitate the encoding and storage of encrypted data through specific biochemical processes. One of the most significant breakthroughs in this domain is the generation of truly random one-time pads, which capitalize on the massively parallel computing capabilities of DNA molecules to achieve enhanced cryptographic security. Furthermore, natural DNA cryptography has demonstrated its utility in cryptanalysis, with one of its earliest major achievements being the successful decryption of the Data Encryption Standard (DES) through brute force attacks that leverage DNA’s intrinsic parallelism to execute large-scale computations with remarkable efficiency [55]-[57]. The second methodology, pseudo-DNA cryptography, shares conceptual similarities with natural DNA cryptography but differs fundamentally in that it does not rely on actual biological material [58]-[60]. Instead, this approach employs theoretical models that simulate DNA structures, applying analogous computational principles to digital data rather than to physical nucleotide sequences. In a typical implementation, a given message is first converted into binary form, after which it is mapped onto a pseudo-DNA sequence that mimics the structure and functional behavior of real DNA. Subsequently, a series of pseudo-DNA operations is performed to enhance the security of existing cryptographic algorithms before the transformed sequence is ultimately translated back into binary and transmitted through a communication channel. By simulating DNA processes in a purely computational framework, pseudo-DNA cryptography provides an alternative means of harnessing DNA's informational properties without the practical limitations associated with biochemical manipulation. The third and final approach, DNA-based steganography, focuses primarily on information concealment rather than encryption [61]-[63]. The term "steganography" originates from the Greek words steganos, meaning "covered," and graphia, meaning "writing," collectively signifying "hidden writing." DNA's inherent complexity and vast sequence variability make it an ideal medium for steganographic techniques, as messages embedded within DNA strands are extraordinarily difficult to detect, extract, or decode. Given the immense number of possible nucleotide arrangements, an adversary attempting to locate a hidden message within a DNA sequence faces an insurmountable computational challenge, making DNA steganography particularly advantageous in the domain of covert communication and data protection.

In recent years, there has been a surge of interest in utilizing DNA as a foundational medium for cryptographic applications, driven by its unique advantages over traditional methods of encryption and data security [64]. DNA-based cryptographic techniques offer several compelling benefits, including an exceptionally high storage capacity, a low error rate during information retrieval, and a remarkable degree of resistance to environmental degradation. However, despite these advantages, the integration of DNA into cryptographic systems presents a series of formidable challenges, including the high cost associated with DNA synthesis and sequencing, the requirement for specialized laboratory equipment and expertise, and the potential for errors during the encoding and decoding processes [49]. To address these challenges, researchers have explored various DNA-based cryptographic methodologies, each of which presents a distinct balance between security, efficiency, and practicality.

This review provides a survey of the three primary categories of DNA-based cryptographic techniques - natural DNA cryptography, pseudo-DNA cryptography, and DNA-based steganography [65]. Natural DNA cryptography exploits the inherent properties of biological DNA molecules to perform encryption and decryption processes, leveraging biochemical reactions for secure information processing. In contrast, pseudo-DNA cryptography operates within a purely computational domain, applying DNA-inspired algorithms to enhance the security and performance of conventional cryptographic systems. Lastly, DNA-based steganography capitalizes on the complexity and unpredictability of DNA sequences to obscure information, offering a highly effective mechanism for covert data transmission. Each of these approaches presents unique strengths and limitations, highlighting the diverse and evolving role of DNA in the broader field of cryptography and secure communication [66]-[69]. By analyzing the current state of research and identifying key challenges, this paper seeks to provide a valuable resource for both researchers and practitioners in the field of cybersecurity. Furthermore, we examine the future directions of DNA-based encryption, considering how these techniques could evolve to address the ever-growing challenges posed by cyber threats and the increasing demand for sustainable digital security solutions.

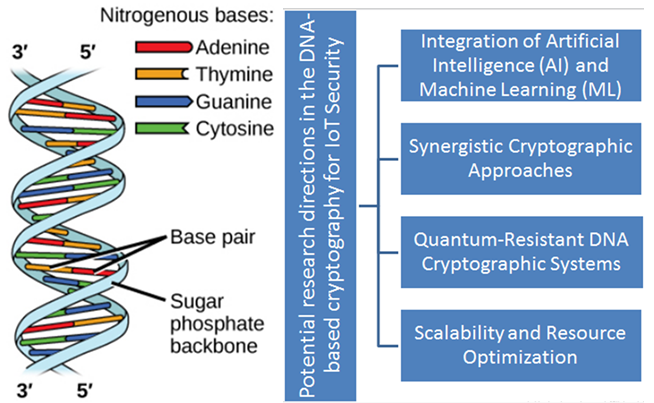

- DNA STRUCTURE

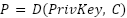

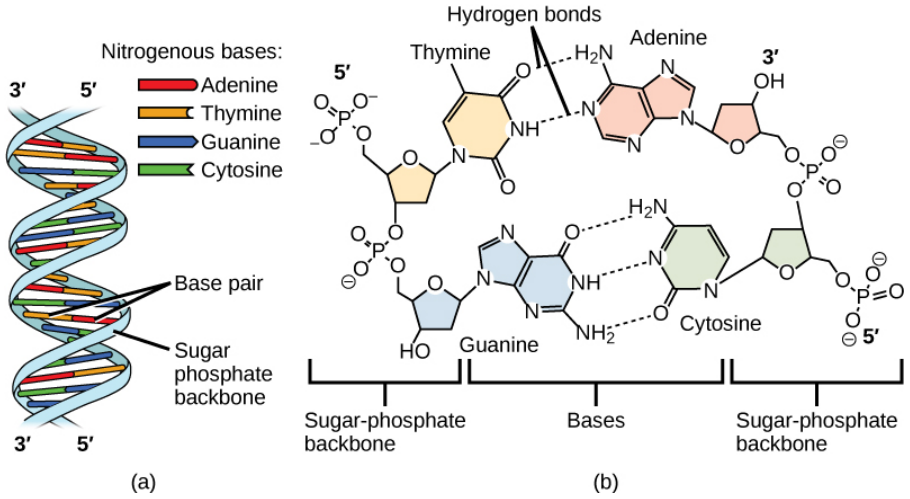

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is composed of fundamental structural units known as nucleotides [70]. Each nucleotide consists of three primary components: a deoxyribose sugar, which is a five-carbon (pentose) sugar; a phosphate group, which contributes to the formation of the DNA backbone; and a nitrogenous base, which is responsible for encoding genetic information (Figure 1). The nitrogenous bases in DNA are classified into two distinct categories based on their molecular structure. The purines, adenine (A) and guanine (G), are characterized by a double-ringed structure, whereas the pyrimidines, cytosine (C) and thymine (T), possess a smaller, single-ringed configuration. The identity of a nucleotide is determined by the specific nitrogenous base it contains, thereby playing a major role in the genetic coding and transmission of hereditary information.

Figure 1. (a) Each DNA nucleotide consists of a sugar, a phosphate group, and a nitrogenous base (b) Cytosine and thymine belong to the pyrimidines, while guanine and adenine are classified as purines. (Reprinted from ref. [70] with permission of OpenStax publisher. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/concepts-biology/pages/9-1-the-structure-of-dna)

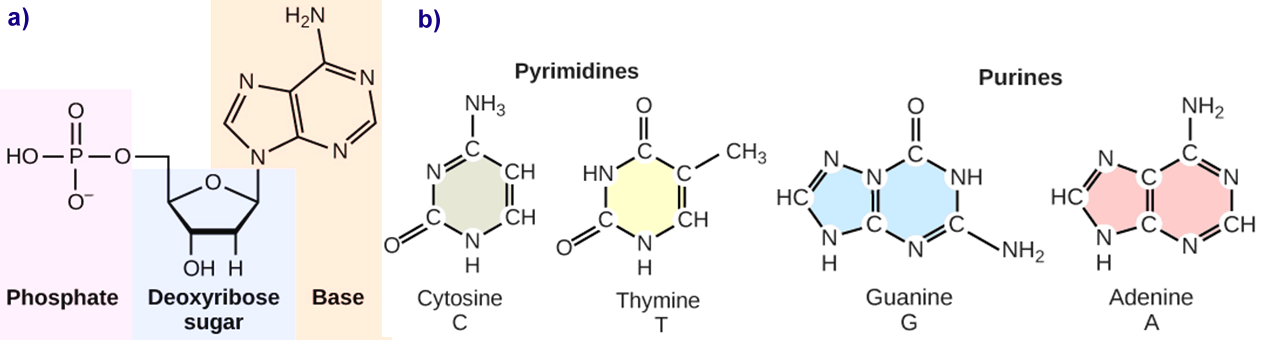

A nucleotide serves as the fundamental unit of DNA, and in its natural state, DNA exists as a double-stranded molecule. These two strands are held together along their entire length by hydrogen bonds that form between complementary nitrogenous bases. The structural organization of DNA was first elucidated by James Watson and Francis Crick [71], who proposed that DNA consists of two polynucleotide strands twisted around each other in a helical arrangement, forming what is known as a right-handed double helix. The stability and specificity of this helical structure are maintained through base-pairing interactions between purine and pyrimidine bases. Specifically, adenine (A), a purine, forms hydrogen bonds exclusively with thymine (T), a pyrimidine, while guanine (G), another purine, pairs specifically with cytosine (C), a pyrimidine. This pairing mechanism is known as complementary base pairing. Adenine and thymine are linked by two hydrogen bonds, whereas guanine and cytosine are connected by three hydrogen bonds, making the G-C pair slightly stronger than the A-T pair. This base-pairing system underlies Chargaff’s rule, which states that in a given DNA molecule, the amount of adenine is always equal to the amount of thymine, and the quantity of guanine is always equal to that of cytosine. The two strands of DNA are arranged in an antiparallel orientation, meaning they run in opposite directions; one strand runs in the 5′ to 3′ direction, while the complementary strand runs in the 3′ to 5′ direction. Furthermore, the uniform diameter of the DNA double helix is a result of the specific base-pairing pattern: a purine (which consists of two rings) always pairs with a pyrimidine (which consists of a single ring). This ensures that the total width of each base pair remains consistent, maintaining a stable and symmetrical helical structure (Figure 2) [70]. This precise molecular organization is fundamental to DNA's role in storing and transmitting genetic information across generations.

In a double-stranded DNA molecule, the total length is determined by the number of base pairs it contains, where each nucleotide (A, T, G, and C) forms a complementary pairing with its respective counterpart. Since DNA consists of two complementary strands, the length of the molecule is measured in base pairs (bp) rather than individual nucleotides. Consequently, if a double-stranded DNA molecule comprises 20 base pairs, its total length is expressed as 20 bp [49].

Figure 2. DNA (a) forms a double stranded helix, and (b) adenine pairs with thymine and cytosine pairs with guanine. (Reprinted from ref. [70] with permission of OpenStax publisher. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/concepts-biology/pages/9-1-the-structure-of-dna)

- Intrinsic Information Content of DNA Molecules

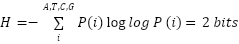

The ability of a given medium to store and transmit information is typically quantified using Shannon information, a fundamental concept in information theory that measures the entropy or uncertainty associated with a data source [52].

In the context of DNA molecules, the maximal self-information (H) of a single nucleotide base is determined by the probability distribution of its occurrence, denoted as P(i), and is mathematically expressed using the base-2 logarithm, which aligns with the standard measurement of digital information in bits. P(i) = 1/4. Under this condition, each nucleotide contributes 2 bits of information, representing the highest possible information capacity per base in a DNA sequence

|

| (5) |

Intrinsic biochemical constraints, such as sequence-dependent stability, enzymatic preferences, and replication fidelity, introduce deviations from the ideal uniform probability distribution. Furthermore, technological constraints associated with DNA synthesis, sequencing, and error correction mechanisms further reduce the effective Shannon information capacity of DNA molecules. Empirical studies, such as those conducted by Erlich and Zielinski [72], have estimated that when accounting for these constraints, the practical Shannon information capacity of DNA molecules is approximately 1.83 bits per base, which is slightly lower than the theoretical maximum of 2 bits. This reduction underscores the impact of biological and technological limitations on DNA-based information storage and retrieval.

- DNA Synthesis and Related Processes

Natural DNA cryptography is a method that employs biological substances within controlled laboratory conditions, wherein molecular manipulations are applied to both naturally occurring and artificially synthesized DNA strands. These manipulations involve intricate biochemical processes that are carried out to encode and decode information securely within the DNA structure. On the other hand, pseudo-DNA cryptography departs from biological operations by replacing them with computational simulations of DNA-related processes, which are executed through algorithmic models on digital systems. This distinction allows for the use of DNA-like constructs without the need for actual biological material, making it a more accessible approach to cryptography.

The following section delves into the fundamental terminology and operational procedures necessary fora comprehensive understanding of DNA-based cryptographic techniques, highlighting the core principles and methodologies employed in both natural and simulated DNA cryptography systems.

- DNA Synthesis

The synthesis of artificial DNA strands is a crucial technique in molecular biology and DNA computing [73]. This process involves the assembly of nucleotide bases within a DNA synthesizer, which operates based on predefined instructions to generate large volumes of synthetic DNA sequences. These sequences are widely used for computational experiments and serve as a foundational resource in DNA-based data storage and cryptographic applications. The ability to produce extensive variations of synthetic DNA at scale has significantly advanced research in bioinformatics and DNA computing [74].

- Gel Electrophoresis for DNA Separation

Gel electrophoresis is an analytical technique used to separate DNA fragments based on their size. It exploits the inherent negative charge of DNA molecules, causing them to migrate toward the positive electrode under an electric field. The gel matrix modulates the migration speed, allowing smaller DNA fragments to travel faster than larger ones. This method provides a reliable means of sorting DNA molecules by length and verifying the presence of specific sequences in a sample [75].

- Denaturation and Annealing of DNA Strands

Denaturation refers to the separation of double-stranded DNA into single strands by applying heat [73], typically within the range of 85°C to 95°C [76]. This process disrupts the weak hydrogen bonds between complementary bases while preserving the stronger phosphodiester bonds in the DNA backbone. Conversely, annealing facilitates the reformation of double-stranded DNA by gradually cooling the single-stranded sequences, enabling complementary strands to rebind through hydrogen bonding [73]. These processes are fundamental in molecular biology, particularly in polymerase chain reactions (PCR) and DNA hybridization techniques.

- Enzymatic Manipulation of DNA

Enzymes play a major role in DNA computing by facilitating modifications and processing of DNA sequences. DNA nucleases, including exonucleases and endonucleases, enable precise trimming and cleavage of DNA strands. Restriction endonucleases, for instance, recognize specific sequences and introduce targeted cuts. DNA polymerases assist in DNA extension by adding nucleotides in a 5′ to 3′ direction, while terminal transferase extends DNA strands at both ends. These enzymatic functions are integral to DNA replication, sequencing, and various computational applications [73].

- Modifying DNA Length

DNA length can be altered using specialized enzymes. Exonucleases degrade DNA from the ends, while endonucleases create internal breaks by cleaving phosphodiester bonds. Restriction endonucleases recognize defined sequences and produce staggered or blunt-ended fragments [77][78]. These processes enable precise DNA modification, facilitating applications in genetic engineering and DNA-based information processing.

- Ligation of DNA Fragments

Ligation is the process of joining two distinct DNA molecules, facilitated by DNA ligase enzymes [76]. This reaction involves the formation of phosphodiester bonds between the hydroxyl and phosphate groups of adjacent DNA strands [79]. The ligation process is widely used in molecular cloning and synthetic biology for assembling recombinant DNA constructs.

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

PCR is a widely utilized technique in DNA amplification, enabling the replication of specific DNA sequences within complex mixtures [77]. The process consists of three primary phases: denaturation, priming, and extension. Initially, DNA is denatured by heat, separating it into single strands. Primers then anneal to complementary sequences, allowing polymerase enzymes to extend the DNA strands and generate copies of the target sequence. The exponential amplification achieved through PCR is crucial for DNA analysis, cryptographic encoding, and forensic investigations.

- DNA Sequencing

The determination of nucleotide sequences within DNA strands is essential for genetic analysis and DNA-based computations. DNA sequencing techniques utilize enzymatic reactions, including polymerase-mediated primer extension and denaturation, to decipher the precise order of nucleotide bases [77]. Gel electrophoresis is often employed to separate and analyze sequencing fragments

- The Central Dogma of Molecular Biology

The central dogma describes the flow of genetic information from DNA to RNA and ultimately to protein synthesis [80]. This framework encompasses three key processes: DNA replication, transcription, and translation. During transcription, DNA is transcribed into messenger RNA (mRNA), where nucleotide sequences are rewritten into RNA bases. In translation, the mRNA sequence is decoded into amino acids, forming proteins. This foundational principle underlies numerous DNA-based cryptographic methods and synthetic biology applications [81].

- DNA Microarrays for Analysis

DNA microarrays, also known as DNA chips, are high-throughput analytical tools used for genetic analysis [82]. These arrays consist of numerous single-stranded DNA probes immobilized on a solid surface. Target DNA samples hybridize with complementary probes, enabling large-scale comparative analysis of genetic variations. DNA microarrays are instrumental in gene expression studies, forensic applications, and personalized medicine.

- DNA Separation Via Hybridization

Hybridization-based separation is a method used to isolate DNA strands containing specific sequences. Complementary probes immobilized on a microarray selectively bind to target DNA sequences, allowing for the extraction and purification of specific strands [73]. This technique is widely used in DNA computing and molecular diagnostics, facilitating sequence-specific identification and sorting [83].

- DNA Digital Coding Techniques

DNA computing encodes binary data into DNA sequences using various mapping techniques [49],[73], [84]. A fundamental method involves representing binary digits with nucleotide pairs based on Watson-Crick complementarity, ensuring valid DNA strand formations. Alternative approaches, such as Clelland’s encoding, use triplet-based mappings to represent characters, numbers, and punctuation.

A key concept in DNA computing is Twin Shuffle (TS) Language, where binary sequences are mapped to complementary DNA strands, preserving computational consistency. TS ensures DNA sequences can be processed within a universal Turing Machine framework, making them viable for algorithmic applications. Further advancements introduce grammatical structures for DNA-based random number generation, where predefined transformation rules guide strand assembly. This approach uses short DNA sequences (algomers) with sticky ends that facilitate structured concatenation, forming complex computational patterns. Another encoding method leverages self-assembling DNA tiles, a concept first introduced by Winfree [85]. These tiles mimic Wang tile systems [86] and can model NP-complete problems, demonstrating Turing universality [85]. DNA tiles have been applied in cryptographic frameworks by encoding binary messages into structured DNA formations, enabling computational security mechanisms. Collectively, these coding techniques underscore DNA’s potential in computation, cryptography, and secure data representation. The inherent complementarity of DNA strands and self-assembly properties provide robust encoding schemes suitable for advanced algorithmic implementations. Table 1 highlights key differences between traditional cryptography and DNA-based cryptography.

Table 1. Comparison of traditional cryptography and DNA-based cryptography

Feature | Traditional cryptography | DNA-based cryptography |

Data representation | Uses binary (0s and 1s) | Encodes data using DNA sequences (A, T, C, G) |

Computational basis | Relies on mathematical algorithms (e.g., RSA, AES) | Uses biological processes, DNA hybridization, and Watson-Crick complementarity |

Processing mechanism | Performed on electronic hardware (CPUs, GPUs) | Conducted through biochemical reactions and DNA computing |

Security strength | Based on computational complexity (factorization, discrete logarithm, etc.) | Provides additional security layers through DNA synthesis, sequencing complexity, and bio-encryption |

Storage density | Limited by digital storage capacity | Extremely high-density storage (DNA can store exabytes of data in a small volume) |

Energy efficiency | Requires electrical power for computation | Energy-efficient, as DNA computing relies on biochemical reactions |

Error sensitivity | Prone to brute-force attacks, quantum computing threats | More resilient to brute-force attacks but sensitive to sequencing and synthesis errors |

Practicality | Widely used in real-world applications | Still in research and experimental phases, with potential future applications |

- NATURAL DNA CRYPTOGRAPHY: METHODS AND APPLICATIONS

Natural DNA cryptography represents a groundbreaking intersection between cryptography and DNA computing, utilizing the inherent biochemical properties of DNA sequences for secure data encryption. This approach capitalizes on the vast combinatorial possibilities of nucleotide arrangements to encode information in a manner that is both robust and resistant to conventional decryption techniques. One of the primary cryptographic methods employed in DNA-based encryption is the one-time pad (OTP) scheme, which offers theoretically unbreakable security due to the complete randomness of the encryption key [87][88]. The OTP encryption model relies on a key that is as long as the message itself, used only once, and kept entirely secret. However, despite its theoretical strength, the practical implementation of OTP encryption faces significant challenges, particularly in the generation, secure storage, and transmission of large, truly random keys.

The earliest cryptographic scheme utilizing DNA was introduced in [89], where the authors proposed an OTP substitution-based approach for DNA encryption, demonstrating its application using a two-dimensional microarray. Chen [90] encrypts plaintext by encoding it within a DNA solution, applying bitwise modulo-2 addition with a one-time pad, and utilizing carbon nanotube-based probes to convert data between DNA and binary storage, ensuring secure encryption through biochemical processes. Chen and Xu [91] introduced a cryptographic approach utilizing self-assembly DNA tiles to address the challenges of time-consuming and labor-intensive biochemical reactions in bio-molecular cryptography, ensuring key uniqueness and randomness within a secure OTP system. Winfree [85]-[92] initially introduced computation with self-assembly DNA tiles, leveraging sticky ends for lattice formation, which later enabled the development of a DNA XOR cryptosystem utilizing random one-time pads through four distinct systems: encryption, ciphertext extraction, key extraction, and decryption, all operating with O(1) input tiles and O(n) steps. Hirabayashi et al. [93][94] proposed a tile-based multi-layer algorithm that enhances fault tolerance by segmenting computations into tiles, allowing error detection and correction across layers to mitigate mismatches. Cheng et al. [95] implemented a DNA tile self-assembly-based algorithm for elliptic curve Diffie-Hellman key exchange, utilizing a structured model to perform scalar multiplication and extract the resulting strand for key generation. Cui et al. [96] proposed a DNA-based encryption scheme leveraging DNA synthesis, PCR amplification, and digital coding, integrating traditional cryptographic principles to enhance security through dual biological and computational safeguards. Tanaka et al. [97] proposed a DNA-based public-key cryptosystem using PCR amplification and sequencing as a one-way function to enable secure key distribution between specific individuals. Namasudra et al. [98] proposed a DNA-based secure data access control model for cloud computing, utilizing a 1024-bit DNA key for encryption and a CSP-managed table for fast data retrieval, enhancing security and efficiency. Table 2 outlines the key methods and applications in the field of natural DNA cryptography.

Table 2. The key methods and applications in the field of natural DNA cryptography

Method | Description & Key Features | Applications |

One-Time Pad (OTP) Encryption | Utilizes a key as long as the message, used once and kept secret. It provides theoretically unbreakable security but faces practical challenges. | Data encryption in secure communications, DNA key exchange protocols. |

Self-Assembly DNA Tiles | Involves DNA tiles self-assembling to facilitate encryption, providing secure key generation and encryption processes. | DNA-based cryptography in secure transmission and public key infrastructure. |

DNA XOR Cryptosystem | Leverages sticky ends for lattice formation to generate random OTPs, enabling encryption and decryption. | Applied in secure data storage, cloud computing, and DNA digital encoding systems. |

Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange | A DNA tile-based approach to key exchange, using elliptic curve cryptography for secure key distribution. | Used in public key systems for secure exchange and cryptographic applications in DNA. |

- PSEUDO-DNA CRYPTOGRAPHY: METHODS AND APPLICATIONS

Pseudo-DNA cryptography represents an advanced encryption paradigm that integrates biological complexity into conventional cryptographic methodologies to fortify the security of binary data [99].

Pseudo-DNA cryptography employs artificially synthesized DNA-like structures as cryptographic keys. These synthetic constructs are designed using modified nucleotides or artificially engineered sequences that emulate the functional characteristics of natural DNA. The fundamental purpose of pseudo-DNA cryptography is to leverage the principles of molecular encoding to enhance security, introduce novel encryption techniques, and improve the resilience of cryptographic systems against potential attacks [49]. Within this framework, various encoding methodologies are employed to transform and secure information while optimizing system performance. These encoding techniques not only introduce complexity into the cryptographic process but also enhance the robustness of the encryption mechanism.

Some of the most prominent coding strategies utilized in pseudo-DNA cryptography include:

- Reverse coding: This technique involves reversing the sequence of the synthetic DNA strand, such that the final nucleotide of the sequence becomes the first and vice versa. By implementing this inversion, an additional layer of computational complexity is introduced, thereby reinforcing the security of the encryption scheme. The reversed sequence deviates from its original form in a non-trivial manner, making unauthorized decryption significantly more challenging.

- Reverse-complement coding: In this method, the DNA sequence undergoes both a reversal and a complementary transformation. Each nucleotide is substituted with its complementary base according to the standard base-pairing rules (A with T and C with G). The dual application of reversal and complementation enhances the cryptographic strength of the encoded information by ensuring that the resulting sequence maintains a defined pairing relationship with the original strand, thereby facilitating precise decryption and error correction.

- GC-content constraints: This encoding strategy imposes specific constraints on the proportion of G and C bases within the artificial DNA sequence. Since the GC-content plays a crucial role in determining the structural stability, hybridization properties, and thermal behavior of DNA molecules, regulating this proportion allows cryptographic systems to optimize parameters such as data integrity, resistance to degradation, and security against cryptanalysis. By tailoring the GC ratio, cryptographic frameworks can achieve improved robustness in both biological and computational environments.

- Homopolymer run-length freedom: Homopolymers are continuous stretches of identical nucleotides within a DNA sequence. Excessively long homopolymer runs may introduce errors in sequencing, synthesis, or decoding, thereby compromising the reliability of the cryptographic process. To mitigate these risks, homopolymer run-length constraints are applied to limit the consecutive repetition of identical nucleotides. This constraint ensures that the encoded sequence remains within predefined structural parameters, enhancing its stability and decoding accuracy.

These encoding methodologies represent only a subset of the diverse strategies available in pseudo-DNA cryptography. Each approach introduces unique constraints and considerations that contribute to the overall security, efficiency, and functional adaptability of the cryptographic system. By integrating these innovative techniques, pseudo-DNA cryptography not only extends the capabilities of traditional encryption but also fosters the development of highly secure and resilient information protection mechanisms [100].

K. Ning [101] pioneered a novel text encryption framework inspired by the central dogma of molecular biology. This approach entails encoding plaintext into DNA-like sequences, which subsequently undergo splicing and translation, culminating in a protein-structured ciphertext. The robustness of this encryption scheme is underpinned by a cryptographic key comprising a genetic code table for translation, alongside precisely defined splicing patterns and locations. By emulating the sophisticated mechanisms inherent in genetic translation, this method substantially enhances resistance to brute-force attacks, offering a highly secure and resilient encryption strategy.

Zhang et al. [102] proposed an image encryption scheme integrating DNA sequence addition and chaos, demonstrating strong resistance to exhaustive, statistical, and differential attacks.

Amin et al. [103] implemented a DNA-based encryption method that leverages DNA's storage capacity and parallelism by encoding binary data into nucleotide sequences, locating their positions within a Canis familiaris genome, and generating a ciphered text as a randomized pointer file, demonstrating robustness against cryptographic attacks.

Tornea et al. [104] proposed a DNA-based encryption system utilizing the binding properties of nucleotide bases and indexing DNA chromosomes as one-time pad structures, implemented through MATLAB Bioinformatics Toolbox to enhance cryptographic security and enable parallel molecular computations.

Liu et al. [105] proposed a novel image encryption scheme integrating confusion and diffusion, where pixel transformation through random nucleotide base-pairing and dynamically generated keys modifies chaotic map conditions, ensuring strong encryption and resistance to common attacks.

Sadeg et al. [106] introduced a symmetric key block cipher algorithm inspired by DNA transcription and translation processes, leveraging DNA’s parallelism and information density for encryption while addressing computational challenges, with experimental results demonstrating strong security and efficiency.

Enayatifar et al. [107] proposed a hybrid image encryption algorithm integrating DNA masking, a genetic algorithm, and a logistic map, where genetic algorithm optimized DNA masks for enhanced encryption quality, demonstrating strong security and resistance to various attacks.

Wang and Zhang [108] explored the integration of DNA computing with cryptographic techniques, demonstrating how RSA encryption can be enhanced through DNA-based encoding to achieve secure and efficient message transmission.

Kalpana and Murali [109] proposed improvements to a DNA-based image encryption algorithm by introducing multiple DNA encoding rules, operations, and a synthetic image combination, using chaotic maps to enhance encryption performance and resistance to statistical and differential attacks.

Mandge and Choudhary [110] presented a DNA encryption technique based on matrix manipulation and secure key generation, highlighting the potential of DNA computing in addressing growing information security concerns due to its high storage capacity, parallelism, and energy efficiency.

Chai et al. [111] proposed a novel image encryption algorithm that combines DNA sequence operations and chaotic systems, utilizing the 2D Logistic-adjusted-Sine map to generate a DNA encoding/decoding rule matrix and applying row and column permutations, DNA XOR operations, and chaotic key matrices to achieve strong encryption and resistance to known attacks.

Prabhu and Adimoolam [112] proposed a novel DNA encryption algorithm that utilizes number conversion, DNA digital coding, and PCR amplification to transform plaintext into ciphertext, offering enhanced security against attacks.

Zefreh [113] proposed a novel image encryption scheme combining DNA computing, chaotic systems, and hash functions, utilizing DNA level permutation and diffusion with new algebraic DNA operators to enhance encryption efficiency and resistance to attacks, while maintaining practicality for real-world applications.

Zhou et al. [114] introduced a DNA self-assembly-based image encryption method, proposing a design scheme using five types of DNA tiles - plaintext, encryption, ciphertext, key, and decryption - to enhance encryption effectiveness, demonstrated through a simulated example.

Li and Chen [115] proposed an image encryption algorithm based on a 6D high-dimensional chaotic system and DNA encoding, utilizing multiple chaos sequences for diffusion and shuffling at both the image and DNA levels, achieving enhanced encryption with superior entropy, pixel correlation, and robustness against geometric and cut-off attacks.

Kolate and Joshi [116] proposed a DNA-based security technique utilizing DNA cryptography and AES encryption to provide multilayer security for transactional data, ensuring confidentiality, integrity, and availability during communication.

Liu et al. [117] proposed an encryption scheme for medical multi-images using the Sin-Arcsin-Arnold Multi-Dynamic random nonadjacent Coupled Map Lattice model and DNA technology, incorporating random key generation, 3D-Fisher for cross-plane scrambling, and asymmetric DNA operations to achieve high-quality diffusion and robust encryption, demonstrating superior NPCR, UACI, and entropy values for medical applications.

Grass et al. [118] presented a strategy combining human genome sequencing and synthetic DNA for secure information storage, using genetic short tandem repeats to generate strong encryption keys, which were experimentally applied to encrypt and recover 17 kB of digital data with a single sequencing run.

Najaftorkaman and Kazazi [119] explored the potential of DNA cryptography in modern information security, proposing a novel method to encrypt data using DNA coding technology to convert binary data into DNA strings, and evaluating the algorithm's strength through DNA strand properties and probability theories.

Alawida [120] proposed a novel DNA and chaotic map-based image encryption algorithm, utilizing a DNA tree to generate secret keys and a new chaotic state machine map for enhanced security, achieving efficient encryption through permutation, substitution, and XOR operations while demonstrating strong resistance to attacks and maintaining fast processing.

Babu et al. [121] proposed a biotic DNA-based secret key cryptographic mechanism utilizing DNA computing’s strengths in ultracompact storage, parallelism, and energy efficiency, employing splicing systems and random multiple key sequences to enhance security, diffusion, and confusion, offering strong resistance to brute-force and chosen ciphertext attacks while ensuring efficient storage, computation, and transmission. Table 3 outlines the key methods and applications in the field of pseudo-DNA cryptography.

Table 3. The key methods and applications in the field of pseudo-DNA cryptography.

Method | Description & key features | Applications |

Reverse coding | Involves reversing the DNA sequence to add complexity to the encryption process. | Enhances data security, especially for encoding sensitive medical or research data. |

Reverse-complement coding | Combines reversal with base-pair complementing, improving cryptographic strength by ensuring pairing relationships with the original strand. | Used in securing medical data, intellectual property, and cloud-based encryption systems. |

Gc-content constraints | Controls the ratio of G and C bases to optimize stability and hybridization properties, enhancing data integrity. | Applied in bioinformatics for encoding genomic data, improving encryption stability. |

Homopolymer run-length freedom | Prevents long runs of identical nucleotides, reducing errors in sequencing and synthesis, while enhancing security. | Used in DNA synthesis for secure key generation in cryptographic systems. |

- DNA-BASED STEGANOGRAPHY: METHODS AND APPLICATIONS

Steganography, the art and science of information concealment, involves embedding a message within a medium in such a way that its existence is imperceptible to external observers [122].

Unlike encryption, which obscures the content of a message, steganography hides its existence altogether. Although its origins can be traced to ancient civilizations, steganography has often been overlooked in modern communication systems, where encryption is more commonly relied upon. Nevertheless, steganography is increasingly gaining attention as a complementary security measure, particularly in scenarios where the mere presence of encrypted data might raise suspicion.

The primary advantage of steganography lies in its ability to make a message invisible rather than merely incomprehensible. Traditionally, steganography has utilized media such as images, audio, or video files, though these forms are limited by the small amount of data that can be concealed without introducing perceptible distortions. DNA, however, offers an unparalleled storage capacity, allowing for the concealment of much larger quantities of data within a much smaller physical space. This unique capability has fueled the development of DNA-based steganography, which exploits the properties of biological material for secure data hiding.

DNA-based steganography was first implemented in [30], using a two-layer approach that embedded messages within the human genome. The first layer involved encoding the message into DNA sequences, while the second layer employed microdot technology to hide the DNA itself. Microdot technology, a well-established form of steganography, reduces images to microscopic sizes, making them easy to conceal within objects such as postage stamps. To enhance the security of the concealed message, Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) amplification was used to replicate the DNA sequences, further obscuring the message. This method ensured that even if an adversary suspected the existence of a hidden message, it would remain undetectable without access to the specific primer sequences, preserving the integrity of the system.

While DNA-based steganography holds immense potential, it is constrained by the limitations of natural DNA cryptography, which is subject to the complexities of biomolecular processes [49]. Although both natural and pseudo-DNA cryptography focus on encrypting information, DNA steganography specifically aims to hide information within DNA sequences.

A critical challenge in steganography is ensuring the hidden message remains imperceptible. DNA's inherent randomness and high data storage capacity make it an ideal medium for this purpose. However, both pseudo-DNA cryptography and DNA steganography often lack thorough security analysis.

For steganography to be effective, standardized frameworks are needed to compare different techniques, and robust steganalysis methods must be developed to assess the effectiveness and security of DNA as a cover medium.

Leier et al. [123] demonstrated two biotechnological cryptographic approaches using DNA binary strands: one employs DNA steganography for secure encryption and decryption, assuming the interceptor has equal technological capabilities as the sender and receiver, while the second integrates graphical subtraction of binary gel-images to create a molecular checksum, which can complement the first method and be used in DNA-based labeling for organic and inorganic materials.

Shimanovsky et al. [124] proposed novel methods for hiding data in DNA and RNA, including techniques for embedding information in non-coding regions and in active coding segments without altering amino acid sequences, using codon redundancy, arithmetic encoding, and public key cryptography, offering potential applications in encryption, authentication, and protection of intellectual property in fields such as medicine, genetics, and DNA computing.

Shiu et al. [125] proposed three DNA-based data hiding methods - the Insertion Method, the Complementary Pair Method, and the Substitution Method - demonstrating how DNA sequence properties can be leveraged to securely embed secret messages, with experimental results showing superior performance in terms of capacity, payload, and robustness compared to competing methods.

Torkaman et al. [126] addressed the increasing demand for secure communications in the face of growing attacker expertise, proposing a new cryptographic protocol based on DNA steganography to conceal session keys, thereby reducing reliance on public key cryptography and preventing attackers from detecting the transmission of sensitive data over insecure channels.

Abbasy et al. [127] propose an algorithm for data hiding in DNA sequences by leveraging binary coding and complementary pair rules to increase complexity, ensuring secure embedding and extraction of a hidden message while analyzing the algorithm's security and robustness.

Liu et al. [128] propose a DNA-based data hiding method that encodes a plaintext message into a DNA sequence, encrypts it using addition operations, embeds it in a Word document by modifying character colors, and ensures security through a large key space resistant to brute force attacks, with experimental results confirming its feasibility.

Subramanian et al. [129] provided a comprehensive review of deep learning-based image steganography methods, categorizing them into traditional, Convolutional Neural Network-based, and Generative Adversarial Network-based approaches, while also summarizing datasets, experimental setups, evaluation metrics, and future research directions to assist researchers in the field.

Majeed et al. [130] provide an overview of text steganography, categorizing methods into statistical and random generation, format-based, and linguistic approaches, analyzing existing techniques, challenges, and future directions while emphasizing the need for imperceptible document modifications to enhance security against attackers.

Wani and Sultan [131] presented a comprehensive review of deep learning-based image steganography techniques, categorizing them into Traditional, Hybrid (Cover Generation, Distortion Learning, Adversarial Embedding), and Fully Deep Learning (GAN Embedding, Embedding Less, Category Label) methods, while analyzing their strengths, weaknesses, and performance on benchmark datasets to highlight areas for future improvement in security, embedding capacity, and invisibility.

Murhty et al. [132] discussed the growing need for secure data transmission in the digital age, emphasizing the limitations of cryptography and steganography as standalone techniques and exploring various strategies that integrate both approaches to enhance data protection against cyber threats.

Sanjalawe et al. [133] proposed a multi-layered steganographic framework that integrates Huffman coding, Least Significant Bit embedding, and a deep learning-based encoder-decoder to enhance imperceptibility, robustness, and security, demonstrating superior performance on benchmark datasets with high structural similarity, robust data recovery, and resistance to common attacks, thereby advancing secure communication and digital rights management.

Majeed et al. [134] analyze the increasing need for protecting confidential image data in network communications, highlighting the advantages of combining encryption and steganography for multi-layered security, discussing emerging technologies, challenges, and evaluation parameters to enhance data protection against intrusions. Table 4 outlines the key methods and applications in the field of DNA-based steganography.

Table 4. The key methods and applications in the field of DNA-based steganography.

Method | Description & Key Features | Applications |

Insertion Method | Embeds data by inserting extra nucleotides into the DNA sequence. It offers good payload capacity. | Used for embedding secret data in genetic sequences, ensuring privacy in genomic data storage. |

Complementary Pair Method | Utilizes DNA's complementary base-pairing to hide data, ensuring that the secret message is difficult to detect. | Applied in secure data communication and protecting intellectual property in genetic research. |

Substitution Method | Replaces certain nucleotides with others to encode hidden data without altering the sequence structure. | Used in encrypted communication systems for hiding sensitive data in genetic sequences. |

Multi-Layered DNA Steganography | Combines multiple DNA-based techniques for improved complexity and security, using amplification and additional encoding layers. | Used in covert communications, ensuring the security of stored and transmitted biological data. |

- SECURITY CHALLENGES IN IoT

The Internet of Things (IoT) constitutes a vast and dynamically evolving ecosystem of interconnected devices, or nodes, that engage in continuous data exchange to execute predefined tasks and achieve designated objectives [135]. The pervasive integration of IoT into modern digital ecosystems has facilitated seamless interconnectivity among everyday objects, enabling the efficient collection, organization, and processing of vast volumes of data [25]-[28]. This technological paradigm shift has catalyzed advancements in critical sectors such as energy distribution, healthcare, intelligent transportation, and other fundamental national infrastructure systems [135].

The IoT ecosystem extends far beyond conventional smart devices, encompassing a vast array of interconnected sensors, actuators, embedded systems, and cloud-based services. These components operate synergistically to enable automation, predictive analytics, and intelligent decision-making, thereby revolutionizing industries and enhancing operational efficiencies. The proliferation of IoT applications has led to significant transformations in various domains, including smart cities, precision agriculture, environmental monitoring, and autonomous vehicular systems. Additionally, IoT-driven innovations facilitate seamless human-computer interactions, optimizing both personal and industrial processes through machine learning and artificial intelligence integration [29]-[32]. However, the expansion of IoT, intrinsically dependent on internet-based infrastructure, has concurrently amplified concerns regarding security, privacy, and trust [29][32]. The heterogeneous and complex nature of IoT networks introduces novel security risks and vulnerabilities that expand the attack surface, thereby increasing the potential for malicious actors to exploit sensitive network data [136][137].

Cyber threats targeting IoT systems range from unauthorized data access and identity spoofing to advanced persistent threats (APTs) and distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks. Given the reliance of critical infrastructures on IoT systems, the ramifications of security breaches can be severe, impacting not only data confidentiality and integrity but also operational continuity and safety. Consequently, ensuring robust security, privacy preservation, and trustworthiness across all IoT architectural layers - namely, the physical device layer, the network layer, and the service-application layer - is imperative for the sustainable deployment of IoT solutions [136][137]. Furthermore, numerous intelligent systems and applications across diverse domains, including logistics, industrial manufacturing, healthcare, and surveillance, operate atop various communication infrastructures.

Despite the technological disparities among these infrastructures, a fundamental objective of IoT is to provide an interoperable framework that supports seamless data transmission and real-time decision-making processes. To achieve this, IoT incorporates an array of cutting-edge technologies, including intelligent sensors, wireless communication protocols, networking mechanisms, advanced data analytics, and cloud computing architectures [135][137]. The integration of blockchain technology into IoT security frameworks is emerging as a promising approach to enhance data integrity and authentication mechanisms. Additionally, edge computing paradigms are being increasingly adopted to reduce latency, enhance data processing capabilities, and mitigate network congestion in large-scale IoT deployments [138][139].

Given that many of these enabling technologies are still in developmental phases, addressing the associated technical complexities - particularly those pertaining to cybersecurity and privacy protection - remains a critical challenge [135]. Common security vulnerabilities in IoT environments include improper device configurations, inadequate implementation of security protocols, and a general lack of user awareness regarding cybersecurity best practices. Furthermore, the absence of standardized security frameworks and regulatory compliance measures exacerbates the risks associated with IoT adoption, necessitating the development of comprehensive security policies and adaptive threat mitigation strategies [28][32].

IoT infrastructures are systematically targeted by adversaries at different architectural layers, including the physical, network, and application layers. Each of these layers imposes distinct security requirements that must be rigorously upheld to mitigate potential threats and safeguard the integrity of IoT systems [135].

At the foundational level, IoT sensors function as interfaces that bridge the physical world with digital systems, enabling real-time data generation and collection. This data is subsequently transmitted through the network layer, which serves as the conduit for communication between interconnected devices and systems. The network layer plays a critical role in ensuring secure data transmission through encryption protocols, intrusion detection systems, and resilient routing mechanisms. Finally, at the application layer, the processed data is made accessible to users, facilitating a range of automated and intelligent decision-making processes. The security of IoT applications hinges on robust access control mechanisms, multi-factor authentication, and continuous security monitoring frameworks [136].

Consequently, ensuring the privacy and trustworthiness of IoT services - particularly those handling sensitive user data, enterprise information, and governmental communications - has emerged as a critical imperative in the continued evolution of IoT technologies. Future advancements in IoT security will necessitate the integration of artificial intelligence-driven threat detection, post-quantum cryptographic techniques, and self-healing cybersecurity systems to mitigate evolving cyber threats effectively. The convergence of IoT with emerging technologies such as 5G, AI, and blockchain will further redefine security paradigms, necessitating a proactive and multi-layered approach to safeguarding the integrity, confidentiality, and availability of IoT systems [140][141].

- Types of Attacks Targeting IoT Systems

As IoT ecosystems continue to expand, the increasing interconnectivity of devices has exposed them to a wide spectrum of cyber threats (physical attacks, network attacks, software attacks, application attacks, authentication and authorization attacks), with attackers exploiting vulnerabilities across multiple layers, thereby compromising security, privacy, and system reliability [137].

- Physical attacks

Physical attacks exploit direct interactions with the hardware components of IoT devices, often requiring close proximity or physical access to execute. These attacks circumvent software-based security mechanisms, rendering devices susceptible to tampering, data extraction, or even permanent damage. Given their localized nature, physical attacks pose a significant threat to critical infrastructure deployments where IoT devices operate in unattended or exposed environments. Techniques such as side-channel attacks, hardware Trojan implantation, and electromagnetic analysis exemplify the sophisticated methods adversaries employ to compromise device integrity and extract sensitive cryptographic information.

- Network attacks