Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro ISSN: 2685-9572

Discount Factor Parametrization for Deep Reinforcement Learning for Inverted Pendulum Swing-up Control

Atikah Surriani 1, Hari Maghfiroh 2, Oyas Wahyunggoro 3, Adha Imam Cahyadi 3, Hanifah Rahmi Fajrin 4

1 Department of Electrical Engineering and Informatics, Vocational Colege, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia

2 Department of Electrical Engineering, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia

3 Department of Electrical and Information Engineering, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia

4 Department of Software Convergence, Soon Chun Hyang University, Republic Korea

ARTICLE INFORMATION |

| ABSTRACT |

Article History: Received 18 March 2024 Revised 09 April 2025 Accepted 12 April 2025 |

|

This study explores the application of deep reinforcement learning (DRL) to solve the control problem of a single swing-up inverted pendulum. The primary focus is on investigating the impact of discount factor parameterization within the DRL framework. Specifically, the Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) algorithm is employed due to its effectiveness in handling continuous action spaces. A range of discount factor values is tested to evaluate their influence on training performance and stability. The results indicate that a discount factor of 0.99 yields the best overall performance, enabling the DDPG agent to successfully learn a stable swing-up strategy and maximize cumulative rewards. These findings highlight the critical role of the discount factor in DRL-based control systems and offer insights for optimizing learning performance in similar nonlinear control problems. |

Keywords: Discount Factor; Single Swing-up Inverted Pendulum; Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL); Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) |

Corresponding Author: Atikah Surriani, Department of Electrical Engineering and Informatics, Vocational Colege, Gadjah Mada University, Jalan Yacaranda Sekip Unit IV, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 55281. Email: atikah.surriani.sie13@ugm.ac.id |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

|

Document Citation: A. Surriani, H. Maghfiroh, O. Wahyunggoro, A. I. Cahyadi, and H. R. Fajrin, “Discount Factor Parametrization for Deep Reinforcement Learning for Inverted Pendulum Swing-up Control,” Buletin Ilmiah Sarjana Teknik Elektro, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 56-67, 2025, DOI: 10.12928/biste.v7i1.10268. |

- INTRODUCTION

Designing control systems for complex and nonlinear dynamical systems traditionally requires a high level of system understanding, including precise physical and configuration models [1]. These conventional approaches often demand strict assumptions and detailed mathematical modeling, which can be challenging for systems with unpredictable behaviors. In contrast, Reinforcement Learning (RL) offers a model-free approach that enables agents to learn control strategies through direct interaction with the environment [2]. RL requires minimal prior knowledge of the system and is particularly well-suited for nonlinear control problems. The fundamental goal of RL is to learn a policy that maps states to actions in a way that maximizes the expected cumulative reward over time [3]. Unlike traditional supervised learning, the agent is not explicitly told which action to take but must instead discover an optimal strategy through trial and error [4].

Over the past decade, RL has increasingly been integrated with deep learning techniques, giving rise to Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL), which is capable of handling high-dimensional input spaces [5]. One of the widely used DRL algorithms is the Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) [6], which is particularly effective in continuous action spaces. In this study, we employ DDPG to address the control problem of a swing-up inverted pendulum, a classic benchmark in nonlinear and underactuated control systems. This problem is significant due to its unstable dynamics and serves as a valuable testbed for evaluating the performance of learning-based control strategies.

A further contribution of this study is the investigation of the role of the discount factor ( ) in deep reinforcement learning and its influence on the convergence of the learning process. Prior studies have shown that the choice of discount factor can significantly impact the learning performance. For instance, [7] demonstrated that adjusting the discount factor affects the quality of the learning process. While [8] discuss Deep Q-Networks (DQN) [8], which operate in discrete action spaces. In contrast, our work focuses on DDPG, which supports high-dimensional, continuous control tasks [9].

) in deep reinforcement learning and its influence on the convergence of the learning process. Prior studies have shown that the choice of discount factor can significantly impact the learning performance. For instance, [7] demonstrated that adjusting the discount factor affects the quality of the learning process. While [8] discuss Deep Q-Networks (DQN) [8], which operate in discrete action spaces. In contrast, our work focuses on DDPG, which supports high-dimensional, continuous control tasks [9].

Additionally, research such as [10] has explored the use of the discount factor as a regularization term in Recurrent Neural Network-based RL algorithms, while [11] analyzed its effect on convergence in discrete DRL and found that a value of  led to optimal performance. The relationship between learning rate and convergence in discrete RL control was also addressed in [12].

led to optimal performance. The relationship between learning rate and convergence in discrete RL control was also addressed in [12].

While these studies provide useful insights, there is a lack of comprehensive analysis regarding how the discount factor influences learning stability and performance in continuous control tasks using DDPG. Therefore, this research aims to fill that gap by evaluating the impact of the discount factor on learning convergence and control performance in the swing-up inverted pendulum scenario.

To summarize, this paper contributes by:

- Applying the DDPG algorithm to solve the continuous control problem of a swing-up inverted pendulum.

- Investigating how varying the discount factor affects convergence speed and policy performance in DDPG-based control.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section II discusses the proposed methodology. Section III presents simulation results and analysis. Finally, Section IV concludes the study and outlines future directions.

- RESEARCH METHOD

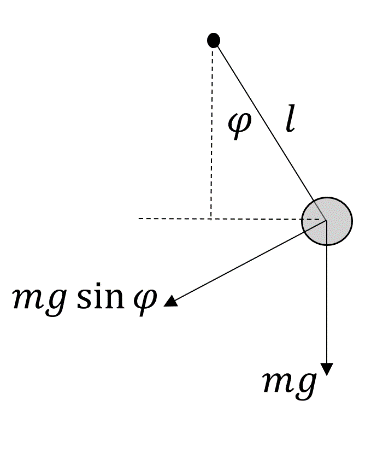

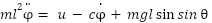

- Single Swing Up Inverted Pendulum

The single swing-up inverted pendulum is a classical control problem widely used to evaluate the performance of control algorithms, particularly in nonlinear and underactuated systems. This system consists of a rigid rod with a mass at the end (bob), capable of rotating about a pivot point. The pendulum starts in a downward vertical position, and the objective is to apply torque at the pivot to swing the pendulum upward and balance it in the unstable upright position.

In its rest state, the pendulum returns to its stable equilibrium due to gravitational force. When displaced and released, the gravitational torque causes oscillatory motion around the equilibrium. The dynamics of the system exhibit nonlinearity and instability, making it a suitable benchmark for evaluating RL-based control strategies. The dynamics of the pendulum can be described using Newton’s second law. Assuming the pivot is actuated, and friction is present, the nonlinear differential equation governing the pendulum’s motion is given by:

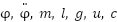

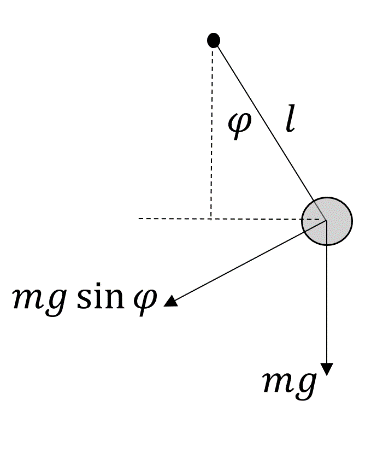

|

| (1) |

Where  are the angular displacement of the pendulum, the angular acceleration, the mass of the pendulum bob (1 kg), the length of the rod (1 m), the gravitational acceleration (9.81 m/s²), the applied torque (control input), and a damping coefficient representing friction at the pivot, respectively.

are the angular displacement of the pendulum, the angular acceleration, the mass of the pendulum bob (1 kg), the length of the rod (1 m), the gravitational acceleration (9.81 m/s²), the applied torque (control input), and a damping coefficient representing friction at the pivot, respectively.

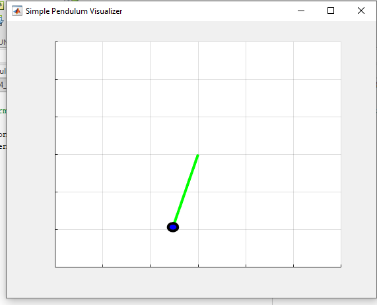

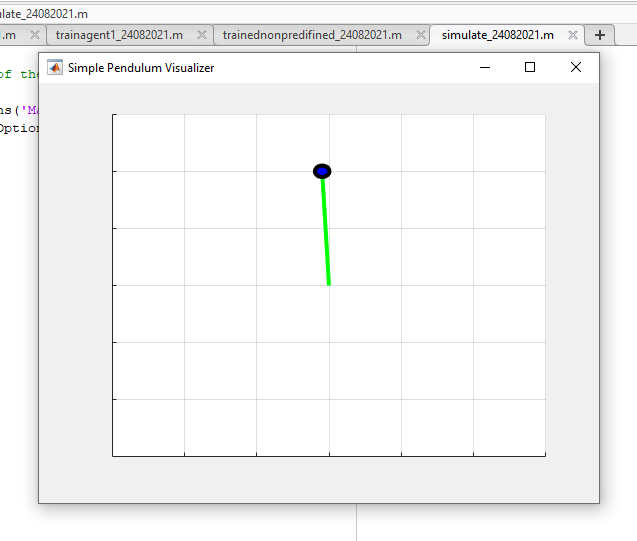

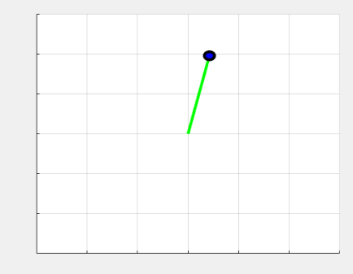

Equation (1) captures the interaction between torque input, gravity, and damping in the pendulum system. This formulation is used as the simulation model within the MATLAB environment. A schematic representation of the single swing-up inverted pendulum is shown in Figure 1. This pendulum system presents a challenging control problem due to its nonlinearity, instability, and under-actuation, making it ideal for testing the capabilities of reinforcement learning algorithms such as DDPG.

Figure 1. A Single Swing Up Inverted Pendulum

- Reinforcement Learning

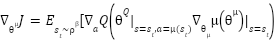

RL is a branch of machine learning focused on solving sequential decision-making problems, particularly in environments where the system dynamics are unknown or partially known. RL is commonly formalized using the Markov Decision Process (MDP) framework, which models an environment in which an agent makes decisions to maximize cumulative rewards over time [13].

An MDP is defined as a 5-tuple  , where,

, where,  is a set of possible states,

is a set of possible states,  is a set of possible action,

is a set of possible action,  is a transition probability function,

is a transition probability function,  is the reward function,

is the reward function,  is a discount factor for future rewards.

is a discount factor for future rewards.

In fully observable environments, the observation at time t is equal to the state:  [14]. When the agent is in state

[14]. When the agent is in state  , it takes an action

, it takes an action  , resulting in a new state

, resulting in a new state  according to the transition probability

according to the transition probability  . The agent also receives a reward,

. The agent also receives a reward,  , or optionally

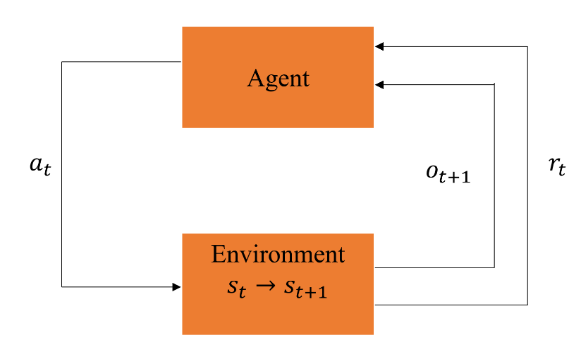

, or optionally  , depending on the design [15]. The objective in RL is to learn an optimal policy that maximizes the expected cumulative reward (also called return) over time. The agent improves its decision-making capability by continuously interacting with the environment, as illustrated in Figure 2.

, depending on the design [15]. The objective in RL is to learn an optimal policy that maximizes the expected cumulative reward (also called return) over time. The agent improves its decision-making capability by continuously interacting with the environment, as illustrated in Figure 2.

The main components of an RL system are, State (s) is the current condition or situation of the agent in the environment, Action (a) is the choice made by the agent to influence the environment. Reward (r) is the feedback signal used to evaluate the agent's performance. Observation (o) is the Information received from the environment, which may or may not fully represent the current state.

At each timestep  , the agent:

, the agent:

- Observes the environment’s state

,

, - Select an action

,

, - Receives a reward

,

, - Transitions to a new state

,

, - Continue learning from the feedback loop.

This agent–environment interaction forms the basis for learning in RL. A more comprehensive discussion on RL fundamentals can be found in [4], which explores value functions, policy learning, exploration strategies, and convergence guarantees.

Figure 2. Reinforcement Learning

- Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG)

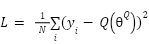

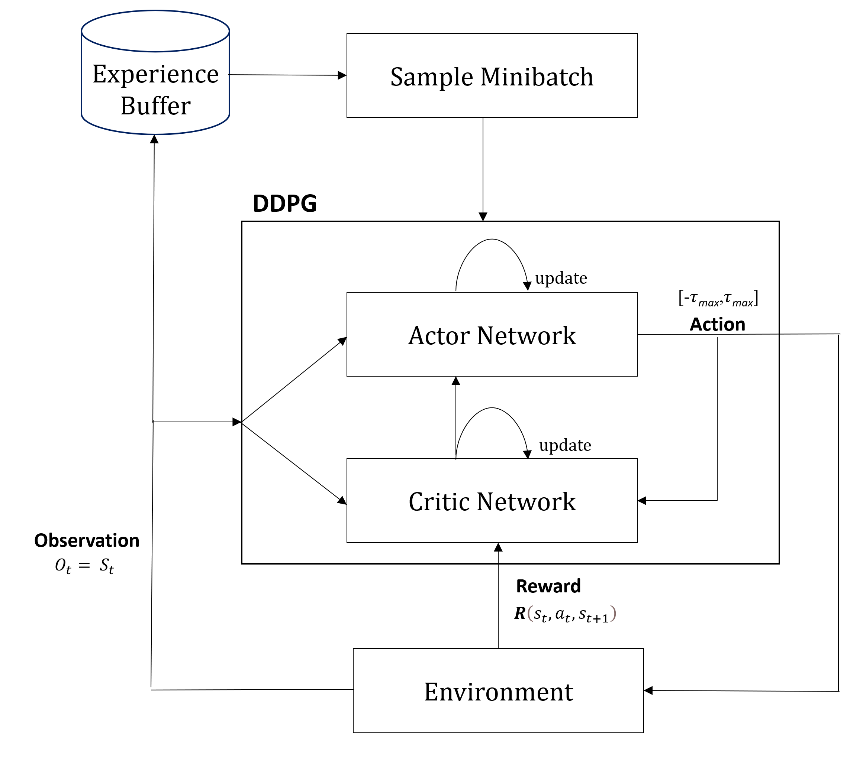

The DDPG algorithm was first introduced in [19]. DDPG is an RL method characterized as a free, online, and off-policy model. It adopts an actor-critic architecture to learn an optimal policy that maximizes the cumulative reward over time [20]. In general, an RL agent consists of two main components: a policy and a learning algorithm. The policy maps observations from the environment to actions, typically approximated by a parameterized function. The learning algorithm updates these parameters based on the feedback—i.e., actions, observations, and rewards—received from the environment. The ultimate goal is to learn a policy that maximizes long-term cumulative reward [21].

DDPG builds upon the Deterministic Policy Gradient (DPG) algorithm, which utilizes both an actor function and a critic function. These are parameterized as follows:

|

| (2) |

|

| (3) |

Where,  is Q-network,

is Q-network,  is deterministic policy function,

is deterministic policy function,  is target Q network,

is target Q network,  is target policy network [1][2]. The actor function specifies the current policy by specifying a state mapping to a specific action [3]. DPG algorithm gets the exact value of action at each moment toward the policy function [4][5].

is target policy network [1][2]. The actor function specifies the current policy by specifying a state mapping to a specific action [3]. DPG algorithm gets the exact value of action at each moment toward the policy function [4][5].

The actor represents the policy function that maps states to actions as:

|

| (4) |

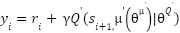

The critic is trained using the Bellman equation, analogous to Q-learning as:

|

| (5) |

The critic network is optimized by minimizing the mean squared error (MSE) between the target  and the current Q-value prediction as:

and the current Q-value prediction as:

|

| (6) |

In DRL, both the actor and critic are modeled using nonlinear function approximators such as neural networks [26]. The actor is trained using the policy gradient, computed from the expected return as:

|

| (7) |

Here,  is the state visitation distribution, which is often omitted for simplification. According to [27], this leads to a practical policy gradient formulation. To stabilize learning and improve performance, experience replay is employed. Transitions of the form

is the state visitation distribution, which is often omitted for simplification. According to [27], this leads to a practical policy gradient formulation. To stabilize learning and improve performance, experience replay is employed. Transitions of the form  are collected into a replay buffer and sampled in minibatches. The weights of the target actor and critic networks are updated using a soft update mechanism:

are collected into a replay buffer and sampled in minibatches. The weights of the target actor and critic networks are updated using a soft update mechanism:

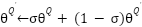

|

| (8) |

|

| (9) |

Where  , ensuring slow updates for stability [22].

, ensuring slow updates for stability [22].

- System Design

The system designed in this study aims to establish an interface between a single swing-up inverted pendulum and an RL algorithm. The swing-up inverted pendulum is modeled as a frictionless system, initially positioned in the downward (hanging) state, defined at an angular position of  rad. The objective of the agent is to apply torque to balance the pendulum in the upright position, defined as 0 rad. Torque acts as the action taken by the agent and operates in a continuous action space within the range [-

rad. The objective of the agent is to apply torque to balance the pendulum in the upright position, defined as 0 rad. Torque acts as the action taken by the agent and operates in a continuous action space within the range [- max,

max, max], specifically from −2 to 2 Nm. Through this interaction, the agent receives observations and rewards based on the consequences of its actions. On the environment side, each time the agent takes an action, it returns a new observation and a reward. The observation vector comprises continuous, unbounded variables:

max], specifically from −2 to 2 Nm. Through this interaction, the agent receives observations and rewards based on the consequences of its actions. On the environment side, each time the agent takes an action, it returns a new observation and a reward. The observation vector comprises continuous, unbounded variables:  ,

,  , and

, and  , where

, where  is the angular displacement of the pendulum and

is the angular displacement of the pendulum and  is its angular velocity. As the system is fully observable, it holds that

is its angular velocity. As the system is fully observable, it holds that  .

.

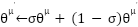

The reward function is defined as:

|

| (10) |

where  is the displacement from the upright position,

is the displacement from the upright position,  is its time derivative, and

is its time derivative, and  is the control signal (torque) applied at the previous time step.

is the control signal (torque) applied at the previous time step.

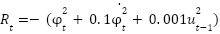

The DDPG algorithm is employed as the learning agent. The DDPG framework consists of two neural networks: an actor network and a critic network. The actor network receives the observation as input and outputs a continuous action. This action is then passed to both the environment and the critic network. The actor network is trained using a deterministic policy gradient approach.

The architecture and parameters of the actor network are as Table 1. The critic network (Table 2) takes the state (observation) and the action (from the actor) as inputs and outputs a Q-value representing the expected return. The critic network is used to guide the actor network during the policy update.

Table 1. Actor Network

Name | Actor |

Input Layer | Observation |

1st fully connected layer | 400 neurons |

2nd fully connected layer | 300 neurons |

Output Layer | Action |

Optimizer | ADAM |

Learning Rate |

|

Gradient Threshold | 1 |

L2 Regulation |

|

Table 2. Critic Network

Name | Actor |

Input Layer | State and Action |

1st fully connected layer | 400 neurons |

2nd fully connected layer | 300 neurons |

1st fully connected layer (Action) | 300 neurons |

Output Layer | Q-value |

Optimizer | ADAM |

Learning Rate |

|

Gradient Threshold | 1 |

L2 Regulation |

|

Figure 3 illustrates the structure of the critic network. To achieve optimal performance, several hyperparameters in the DDPG algorithm need to be carefully tuned. One of the critical hyperparameters is the discount factor  , which determines the importance of future rewards in the learning process.

, which determines the importance of future rewards in the learning process.

The discount factor  influences the agent's balance between short-term and long-term rewards and plays a key role in convergence during training [28]. Although the original DDPG paper did not specify a fixed value for

influences the agent's balance between short-term and long-term rewards and plays a key role in convergence during training [28]. Although the original DDPG paper did not specify a fixed value for  , various studies have used different values based on task complexity:

, various studies have used different values based on task complexity:

: Used in [29] to control a 6-DOF robotic arm,

: Used in [29] to control a 6-DOF robotic arm, : Applied in [30] for a 7-DOF robotic task involving pushing and pulling doors,

: Applied in [30] for a 7-DOF robotic task involving pushing and pulling doors, : Used in [31] for bipedal walking control.

: Used in [31] for bipedal walking control.

However, [32] argues that for continuous control benchmarks, the discount factor may not significantly affect performance. In this study, we explore three different values of  ,

,  , and

, and  . These values are evaluated on the single swing-up inverted pendulum task. Controlling the inverted pendulum is inherently challenging because its natural equilibrium point lies in the downward position. The agent must learn to apply torque effectively to swing the pendulum upwards and maintain balance at the unstable equilibrium point.

. These values are evaluated on the single swing-up inverted pendulum task. Controlling the inverted pendulum is inherently challenging because its natural equilibrium point lies in the downward position. The agent must learn to apply torque effectively to swing the pendulum upwards and maintain balance at the unstable equilibrium point.

Figure 3. Critic Network [6]

- RESULT AND DISCUSSION

- Hyperparameter Setting and Training Configuration

The training process of the DDPG agent begins with setting key hyperparameters, including the target smoothing factor, mini-batch size, and discount factor. These parameters influence learning stability and convergence. Table 3 presents the chosen hyperparameters.

Table 3. DDPG Hyperparameter

Parameter | Value |

Target Smooth Factor ( |

|

Mini Batch Size | 128 |

Discount Factor | 0.900/0.990/0.999 |

The DDPG algorithm adopts the replay buffer concept from Deep Q-Networks (DQN) [33], which stores past experiences to improve learning efficiency. By randomly sampling mini-batches from this buffer, the algorithm avoids correlated updates and enhances training stability [34]. The overall DDPG flow is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Flow chart of DDPG [7]

To encourage exploration during training, DDPG uses Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) noise in the action selection process [35]. Furthermore, it employs a soft update mechanism for the target network to ensure smoother updates. The role of the discount factor is particularly important in computing the target Q-value. As described in Eq. (5), if  is a terminal state, the target value

is a terminal state, the target value  becomes the immediate reward

becomes the immediate reward  ; otherwise, it is computed as the sum of the reward and the discounted future value. The pseudo code of the DDPG algorithm for the training process is shown as follows,

; otherwise, it is computed as the sum of the reward and the discounted future value. The pseudo code of the DDPG algorithm for the training process is shown as follows,

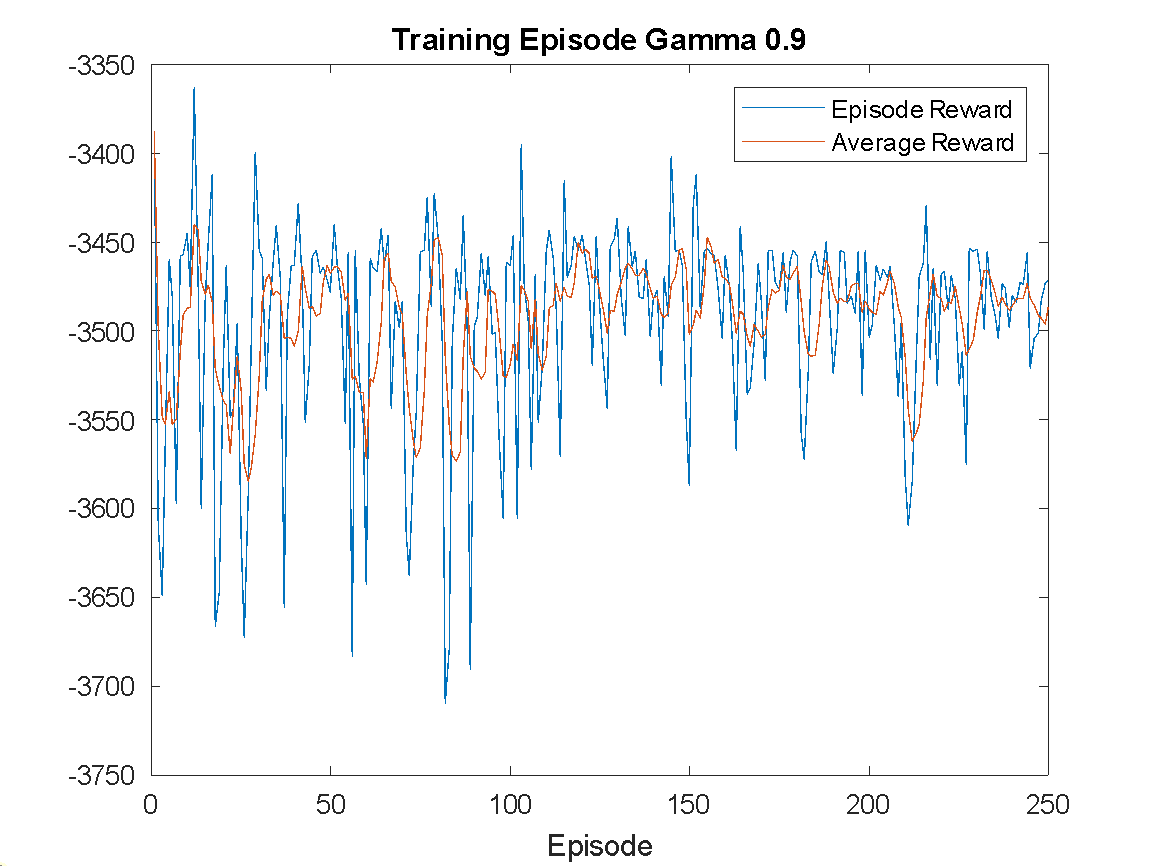

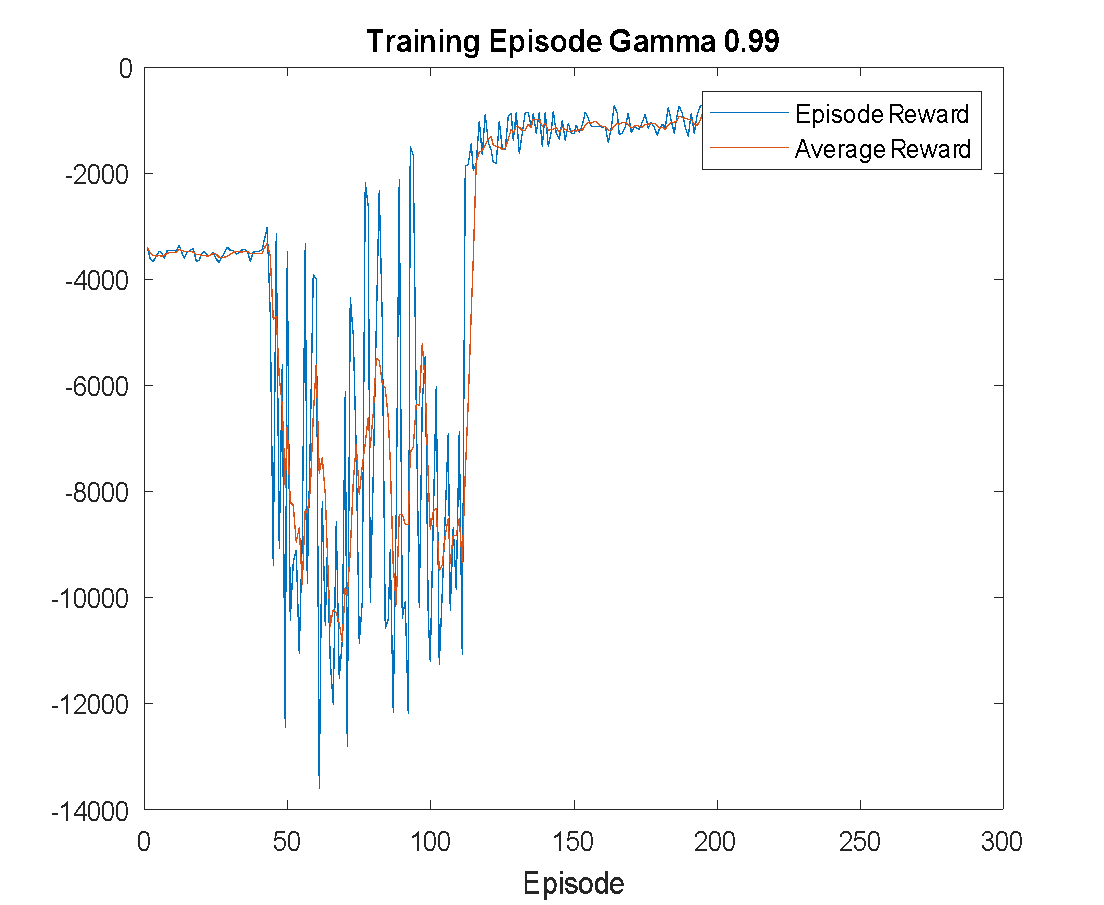

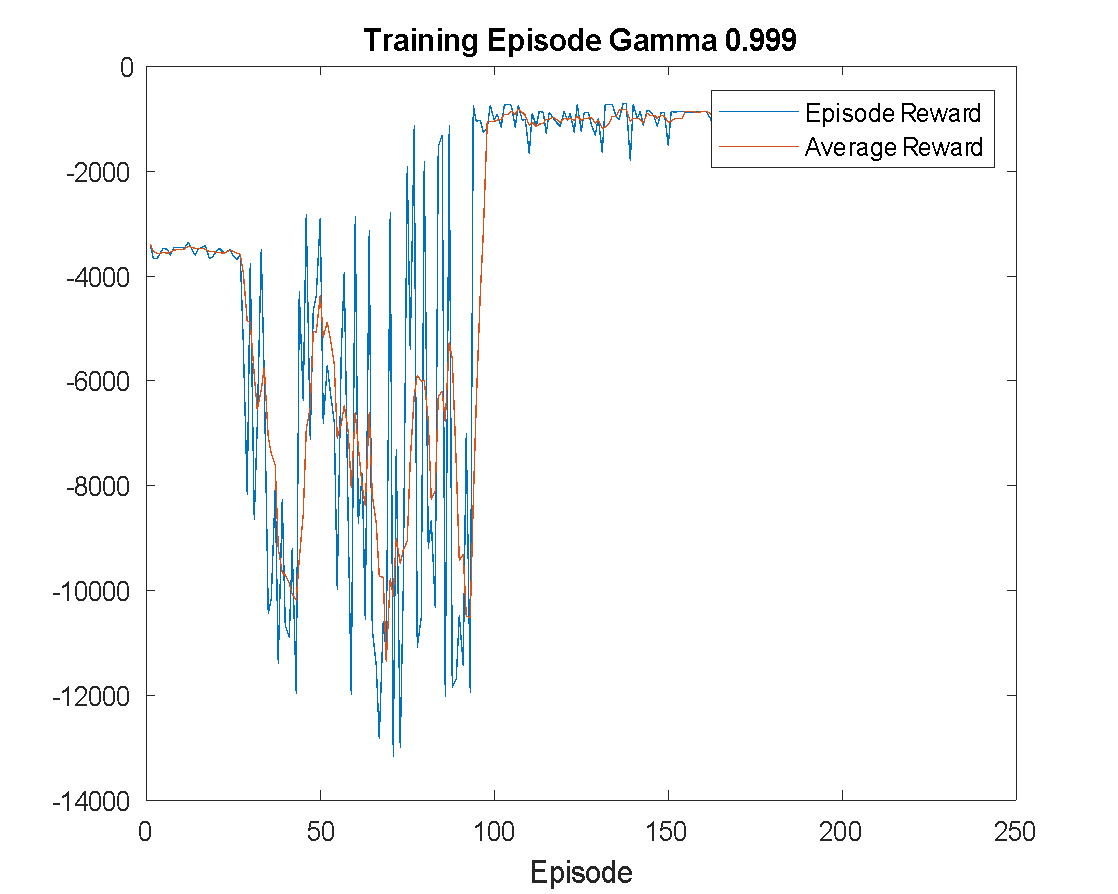

The training is configured to run for a maximum of 250 episodes, and it is terminated early if the average reward surpasses -740. Training results with different discount factor settings are shown in Figure 5. As shown in Figure 5(a), training with  fails to reach the reference reward, indicating a lack of convergence. With

fails to reach the reference reward, indicating a lack of convergence. With  in Figure 5(b), the agent successfully achieves the target reward and converges. Similarly, training with

in Figure 5(b), the agent successfully achieves the target reward and converges. Similarly, training with  (Figure 5(c) also converges but less efficiently than

(Figure 5(c) also converges but less efficiently than  . The results suggest

. The results suggest  as the most effective setting.

as the most effective setting.

|

|

(a) Training Episode with  | (b) Training Episode with  |

|

(c) Training Episode with  |

Figure 5. Training Episode

- Evaluation of Training Results

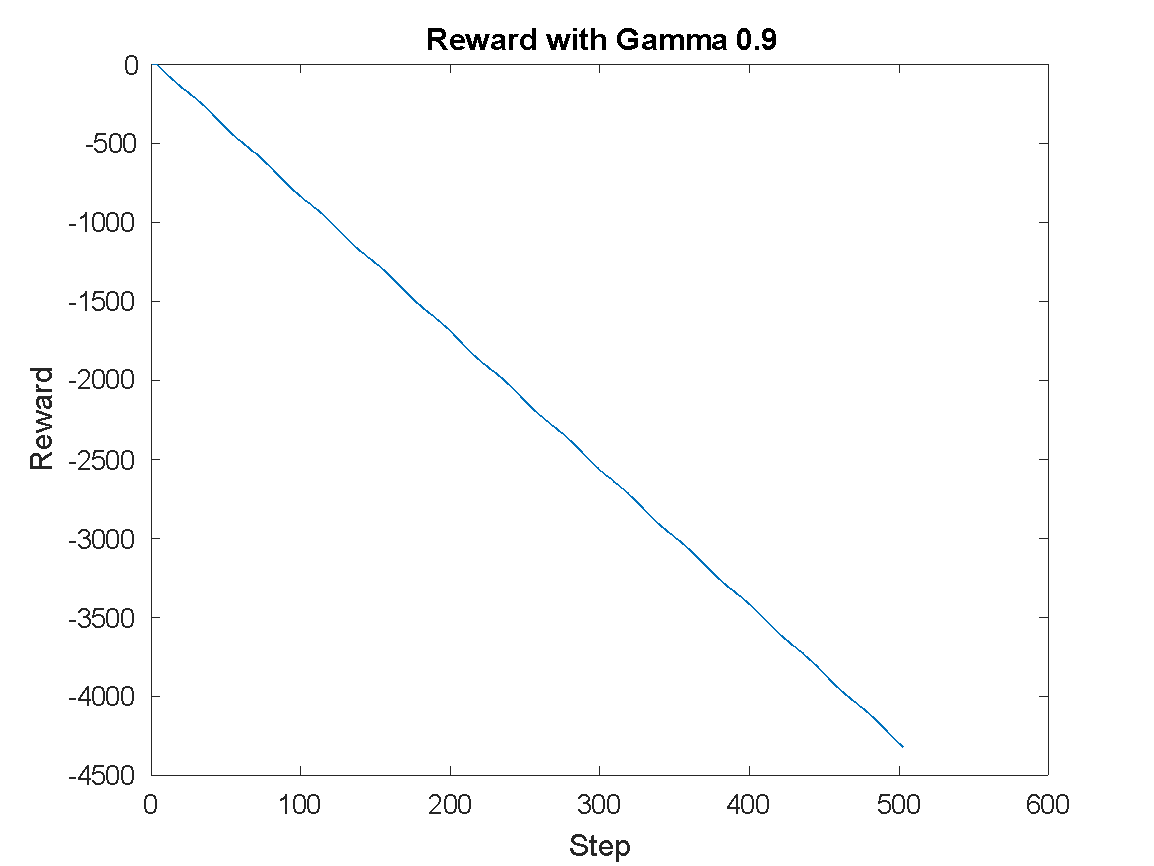

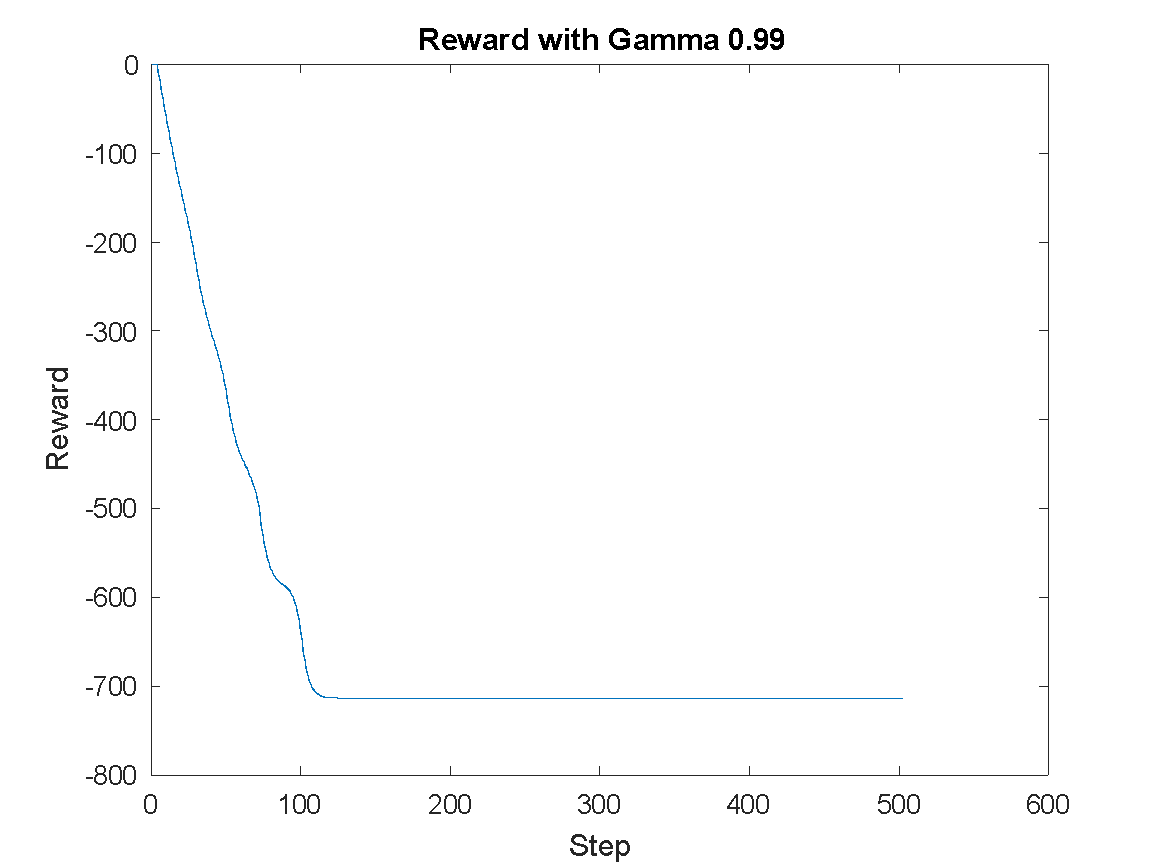

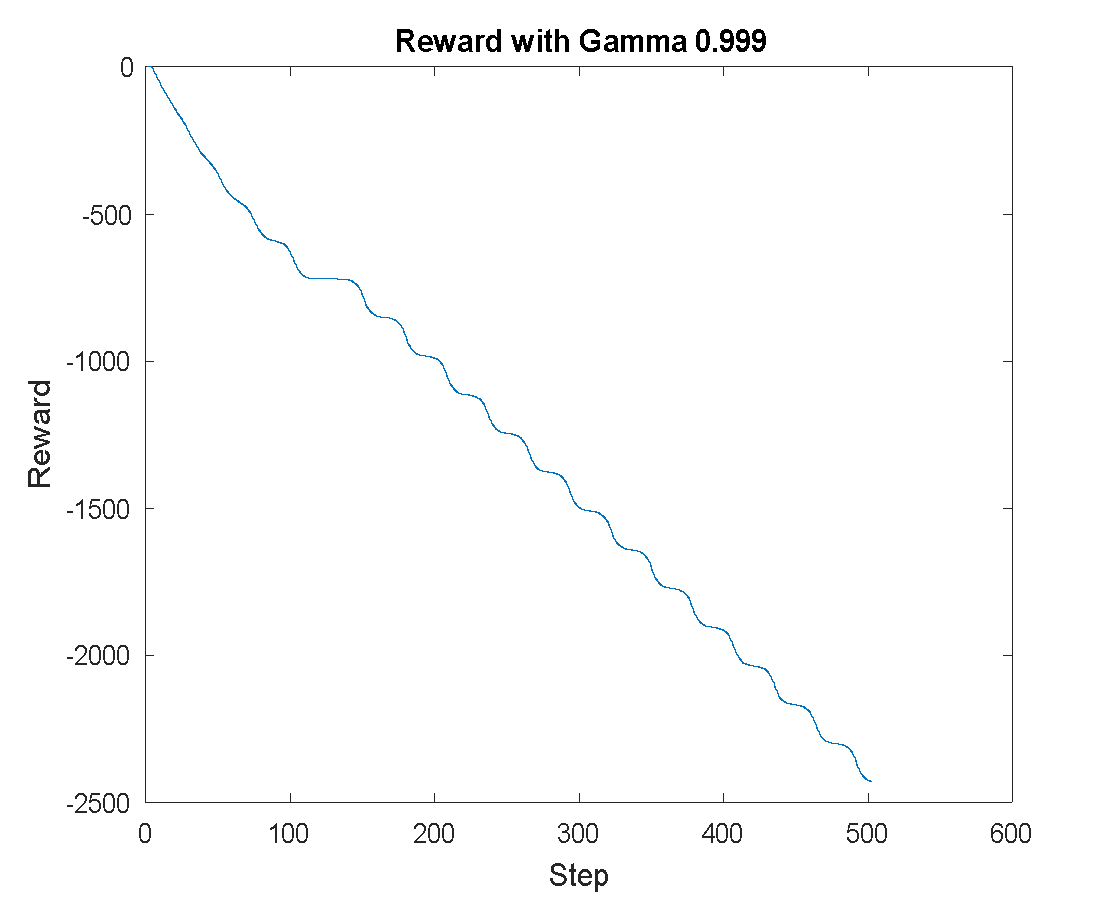

The reward performance per training step is shown in Figure 6. With  , the accumulated reward decreases significantly to -4334 (Figure 6(a)). In contrast,

, the accumulated reward decreases significantly to -4334 (Figure 6(a)). In contrast,  achieves the best cumulative reward of -714.28 (Figure 6(b)), while

achieves the best cumulative reward of -714.28 (Figure 6(b)), while  results in a less optimal reward of -2428.4 (Figure 6(c)).

results in a less optimal reward of -2428.4 (Figure 6(c)).

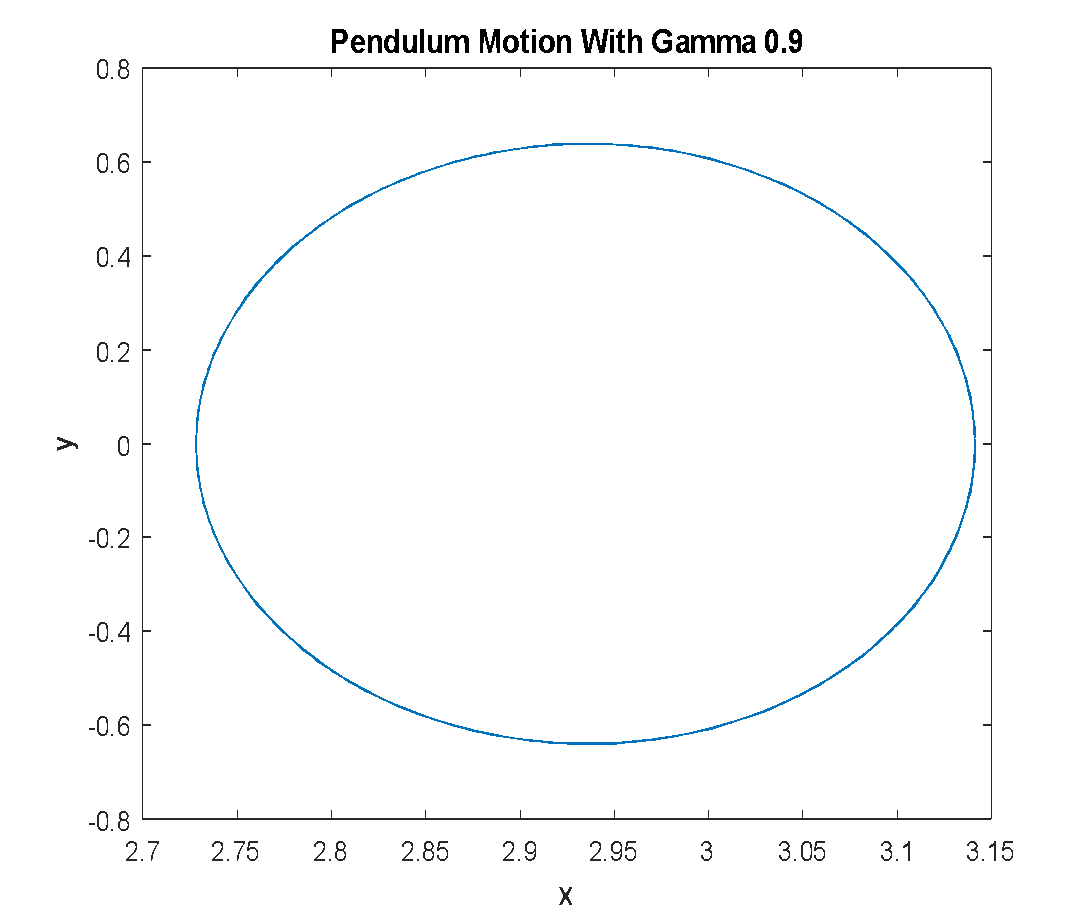

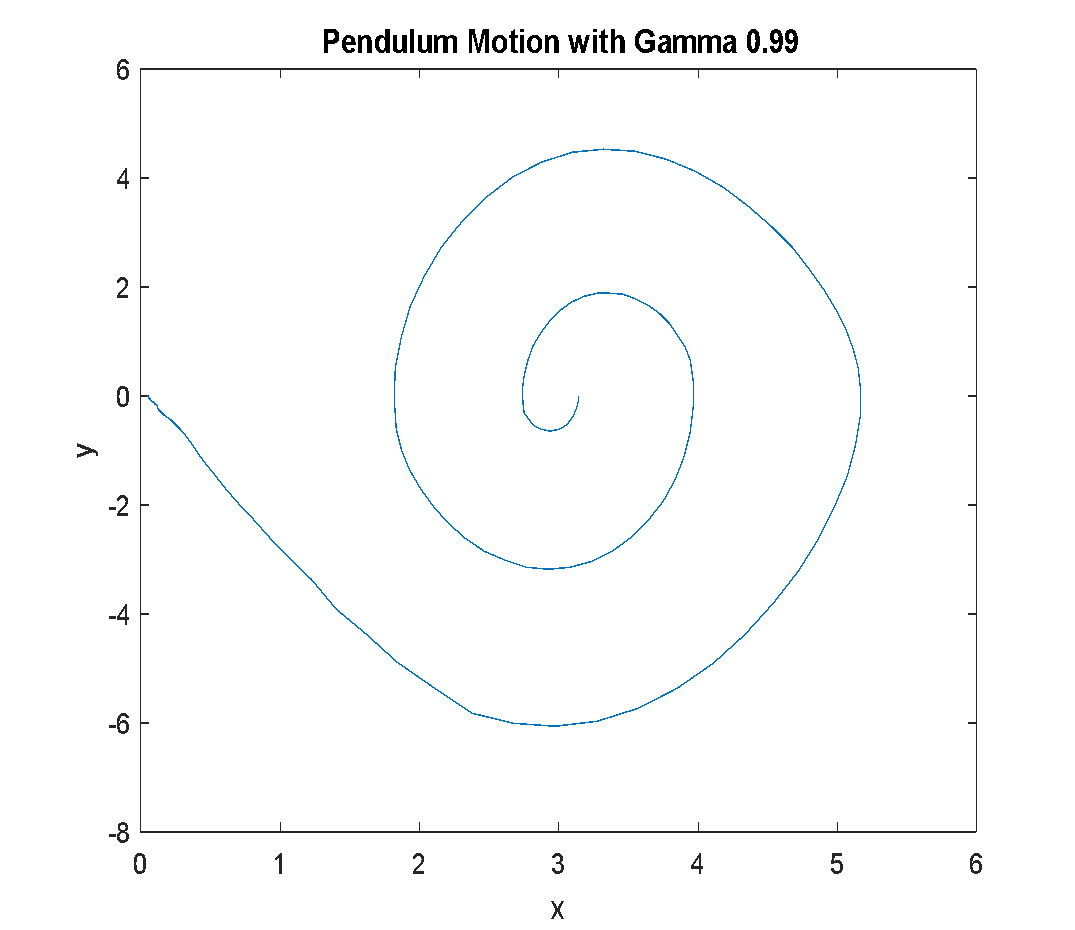

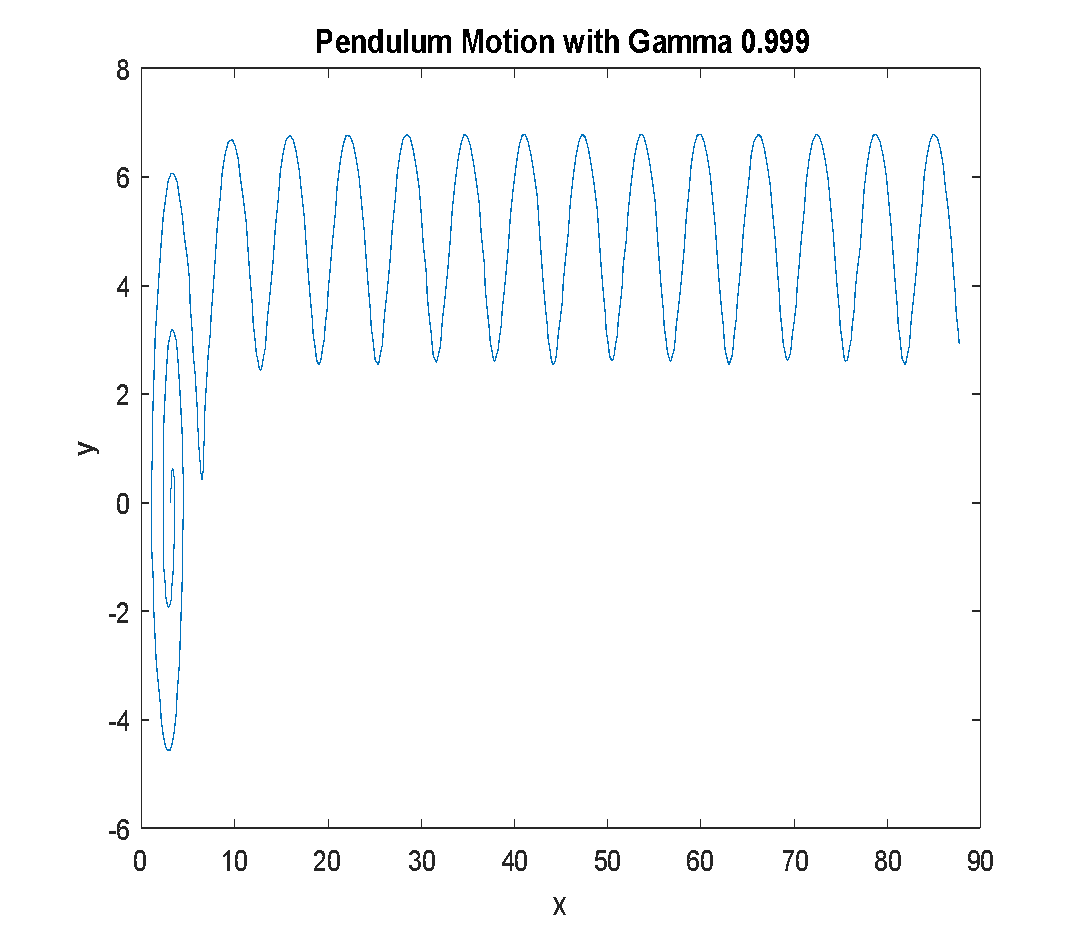

The effect of discount factor settings on the pendulum's behavior is shown in Figure 7. With γ = 0.900, the pendulum fails to reach the upright position (Figure 7(a)). With  , the pendulum successfully swings up and stabilizes near the vertical position (Figure 7(b)). In comparison,

, the pendulum successfully swings up and stabilizes near the vertical position (Figure 7(b)). In comparison,  causes the pendulum to oscillate and overshoot, indicating less stability (Figure 7(c)). Post-training simulation confirms the accumulated total rewards, as presented in Table 4.

causes the pendulum to oscillate and overshoot, indicating less stability (Figure 7(c)). Post-training simulation confirms the accumulated total rewards, as presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Total Reward

Discount Factor | Total Reward |

0.900 | -4334.0 |

0.990 | -714.4 |

0.999 | -2428.4 |

Figure 8 illustrates the pendulum's behavior during the final swing-up simulation. The best performance is observed with  , where the pendulum transitions smoothly to an upright position (Figure 8 (b)). With

, where the pendulum transitions smoothly to an upright position (Figure 8 (b)). With  , the pendulum fails to swing up (Figure 8(a)), while

, the pendulum fails to swing up (Figure 8(a)), while  exhibits excessive oscillation (Figure 8(c)). Overall, the choice of the discount factor γ significantly affects the learning efficiency and performance of the DDPG agent. In this study,

exhibits excessive oscillation (Figure 8(c)). Overall, the choice of the discount factor γ significantly affects the learning efficiency and performance of the DDPG agent. In this study,  achieves the best trade-off between future reward consideration and convergence stability. This confirms that a well-tuned discount factor can improve control performance in continuous action tasks like the swing-up inverted pendulum.

achieves the best trade-off between future reward consideration and convergence stability. This confirms that a well-tuned discount factor can improve control performance in continuous action tasks like the swing-up inverted pendulum.

The discount factor plays a critical role in computing cumulative reward and guiding the agent’s foresight. It influences how far into the future the agent considers potential rewards when selecting actions. Specifically, in DDPG, the agent selects action  for state

for state  using the target actor and receives a reward computed by the target critic. The environment and control task characteristics should influence the selection of

using the target actor and receives a reward computed by the target critic. The environment and control task characteristics should influence the selection of  . In this case,

. In this case,  proves optimal for balancing immediate and delayed rewards in a continuous action domain like the swing-up pendulum. It enables the agent to complete training efficiently and attain a control policy that performs with high stability and precision. These findings not only align with standard reinforcement learning theory but also emphasize the importance of carefully tuning

proves optimal for balancing immediate and delayed rewards in a continuous action domain like the swing-up pendulum. It enables the agent to complete training efficiently and attain a control policy that performs with high stability and precision. These findings not only align with standard reinforcement learning theory but also emphasize the importance of carefully tuning  for control-oriented applications.

for control-oriented applications.

|

|

(a) reward with  | (b) reward with  |

|

(c) reward with  |

Figure 6. Reward of Training

|

|

|

(a) Pendulum motion with  | (b) Pendulum motion with  | (c) Pendulum motion with  |

Figure 7. Pendulum Motion

|

|

|

(a) Swing up the inverted pendulum with  | (b) Swing up the inverted pendulum with  | (c) Swing up the inverted pendulum with  |

Figure 8. A swing-up inverted pendulum

- CONCLUSIONS

This study investigates the impact of the discount factor ( ) in the DDPG algorithm on learning performance in a continuous control task involving a swing-up inverted pendulum. The research highlights the importance of tuning this hyperparameter to ensure convergence and improve the quality of the learned policy. Through comparative simulation, it was found that a discount factor of 0.990 provides the most effective balance between immediate and future rewards, enabling the agent to achieve stable and successful pendulum swing-up control with high cumulative rewards.

) in the DDPG algorithm on learning performance in a continuous control task involving a swing-up inverted pendulum. The research highlights the importance of tuning this hyperparameter to ensure convergence and improve the quality of the learned policy. Through comparative simulation, it was found that a discount factor of 0.990 provides the most effective balance between immediate and future rewards, enabling the agent to achieve stable and successful pendulum swing-up control with high cumulative rewards.

The findings contribute to the field of deep reinforcement learning by emphasizing the role of the discount factor in continuous control scenarios, which is often overlooked in hyperparameter studies. Practically, this insight can be valuable in optimizing DRL algorithms for real-world control systems such as robotic arms, balance systems, or autonomous vehicles, where long-term stability and precise action planning are critical.

For future work, this approach can be extended to investigate other critical hyperparameters in DDPG, explore different actor-critic methods, or apply the optimized framework to more complex multi-degree-of-freedom control environments. Comparative analysis with alternative DRL algorithms may also uncover further enhancements in performance.

REFERENCES

- M. Hesse, J. Timmermann, E. Hüllermeier, and A. Trächtler, “A reinforcement learning strategy for the swing-up of the double pendulum on a cart,” Procedia Manufacturing, vol. 24, pp. 15–20, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2018.06.004.

- C. A. M. Escobar, C. M. Pappalardo, and D. Guida, “A parametric study of a deep reinforcement learning control system applied to the swing-up problem of the cart-pole,” Applied Sciences, vol. 10, no. 24, pp. 1–19, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/app10249013.

- T. Morimura, H. Hachiya, M. Sugiyama, T. Tanaka, and H. Kashima, Parametric return density estimation for reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1203.3497, 2012, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1203.3497.

- S. Meyn. Control systems and reinforcement learning. Cambridge University Press. 2022. https://books.google.co.id/books?hl=id&lr=&id=UZNsEAAAQBAJ.

- Y. Tsurumine, Y. Cui, E. Uchibe, and T. Matsubara, “Deep reinforcement learning with smooth policy update: Application to robotic cloth manipulation,” Robotics and Autonomous Systems, vol. 112, pp. 72–83, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.robot.2018.11.004.

- S. Bhagat, H. Banerjee, Z. H. Tse, and H. Ren, “Deep reinforcement learning for soft, flexible robots: Brief review with impending challenges,” Robotics, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 4, 2019, https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics8010004.

- V. François-Lavet, R. Fonteneau, and D. Ernst, “How to discount deep reinforcement learning: Towards new dynamic strategies. arXiv preprint arXiv:1512.02011, 2015, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1512.02011.

- R. Liessner, J. Schmitt, A. Dietermann, and B. Bäker, “Hyperparameter optimization for deep reinforcement learning in vehicle energy management,” in Proc. 11th Int. Conf. Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART), vol. 2, pp. 134–144, 2019, https://doi.org/10.5220/0007364701340144.

- R. He, H. Lv, S. Zhang, D. Zhang, and H. Zhang, “Lane following method based on improved DDPG algorithm,” Sensors, vol. 21, no. 14, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/s21144827.

- R. Amit, R. Meir, and K. Ciosek, “Discount factor as a regularizer in reinforcement learning,” In International conference on machine learning, pp. 269-278, 2020, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2007.02040.

- A. Sharma, R. Gupta, K. Lakshmanan, and A. Gupta, “Transition based discount factor for model free algorithms in reinforcement learning,” Symmetry, vol. 13, no. 7, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/sym13071197.

- A. Franceschetti, E. Tosello, N. Castaman, and S. Ghidoni, "Robotic arm control and task training through deep reinforcement learning," in Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Autonomous Syst., pp. 532–550, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-95892-3_41.

- A. Franceschetti, E. Tosello, and N. Castaman, “Robotic arm control and task training through deep reinforcement learning,” In International Conference on Intelligent Autonomous Systems, pp. 532-550, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-95892-3_41.

- J. Baek, H. Jun, J. Park, H. Lee, and S. Han, “Sparse variational deterministic policy gradient for continuous real-time control,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron., vol. 68, no. 10, pp. 9800–9810, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2020.3021607.

- A. Géron. Hands-on machine learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras, and TensorFlow: Concepts, tools, and techniques to build intelligent systems. " O'Reilly Media, Inc.". 2022. https://books.google.co.id/books?hl=id&lr=&id=X5ySEAAAQBAJ.

- Y. Zheng, S. W. Luo, and Z. A. Lv, “Active exploration planning in reinforcement learning for inverted pendulum system control,” in Proc. Int. Conf. Machine Learning and Cybernetics (ICMLC), vol. 2006, no. Aug., pp. 2805–2809, 2006, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICMLC.2006.259002.

- A. Zeynivand and H. Moodi, "Swing-up Control of a Double Inverted Pendulum by Combination of Q-Learning and PID Algorithms," 2022 8th International Conference on Control, Instrumentation and Automation (ICCIA), pp. 1-5, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCIA54998.2022.9737201.

- D. R. Rinku and M. AshaRani, “Reinforcement learning based multi-core scheduling (RLBMCS) for real-time systems,” Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng., vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 1805–1813, 2020, https://doi.org/10.11591/ijece.v10i2.pp1805-1813.

- T. P. Lillicrap et al., “Continuous control with deep reinforcement learning,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1509.02971, 2015, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1509.02971.

- S. Wen, J. Chen, S. Wang, H. Zhang, and X. Hu, “Path planning of humanoid arm based on deep deterministic policy gradient,” in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Robot. Biomimetics (ROBIO), pp. 1755–1760, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1109/ROBIO.2018.8665248.

- L. Fan et al., “Optimal scheduling of microgrid based on deep deterministic policy gradient and transfer learning,” Energies, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 1–15, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/en14030584.

- A. Ilyas, L. Engstrom, S. Santurkar, D. Tsipras, F. Janoos, L. Rudolph, and A. Madry, “A closer look at deep policy gradients,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1811.02553, 2018, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1811.02553.

- C. A. M. Escobar, C. M. Pappalardo, and D. Guida, “A parametric study of a deep reinforcement learning control system applied to the swing-up problem of the cart-pole,” Applied Sciences, vol. 10, no. 24, pp. 1–19, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/app10249013.

- O. Sigaud and F. Stulp, “Policy search in continuous action domains: An overview,” Neural Networks, vol. 113, pp. 28–40, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2019.01.011.

- M. Riedmiller, J. Peters, and S. Schaal, “Evaluation of policy gradient methods and variants on the cart-pole benchmark,” in Proc. IEEE Symp. Approximate Dynamic Programming and Reinforcement Learning (ADPRL), pp. 254–261, 2007, https://doi.org/10.1109/ADPRL.2007.368196.

- V. François-Lavet et al., “An introduction to deep reinforcement learning,” Found. Trends Mach. Learn., vol. 11, no. 3–4, pp. 219–354, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1561/2200000071.

- E. H. H. Sumiea et al., "Enhanced Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient Algorithm Using Grey Wolf Optimizer for Continuous Control Tasks," in IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 139771-139784, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3341507.

- D. Bates, “A hybrid approach for reinforcement learning using virtual policy gradient for balancing an inverted pendulum,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.08362, 2021, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2102.08362.

- R. Zeng et al., “Manipulator control method based on deep reinforcement learning,” in Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), pp. 415–420, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/CCDC49329.2020.9164440.

- S. Gu, E. Holly, T. Lillicrap, and S. Levine, “Deep reinforcement learning for robotic manipulation with asynchronous off-policy updates,” in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Robot. Autom. (ICRA), pp. 3389–3396, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRA.2017.7989385.

- C. Liu, A. G. Lonsberry, M. J. Nandor, M. L. Audu, A. J. Lonsberry, and R. F. Kirsch, “Reinforcement learning-based lower extremity exoskeleton control for sit-to-stand assistance,” in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Rehabil. Robot. (ICORR), pp. 328–333, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICORR.2019.8779493.

- B. Singh, R. Kumar, and V. P. Singh, “Reinforcement learning in robotic applications: a comprehensive survey,” Artificial Intelligence Review, vol. 55, no. 2, pp. 945-990, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-021-09997-9.

- Y. Yang, Z. Guo, H. Xiong, D. -W. Ding, Y. Yin and D. C. Wunsch, "Data-Driven Robust Control of Discrete-Time Uncertain Linear Systems via Off-Policy Reinforcement Learning," in IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, vol. 30, no. 12, pp. 3735-3747, Dec. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2019.2897814.

- Y. Duan, X. Chen, R. Houthooft, J. Schulman, and P. Abbeel, “Benchmarking deep reinforcement learning for continuous control,” In International conference on machine learning, pp. 1329-1338, 2016, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1604.06778.

- T. Seyde, P. Werner, W. Schwarting, I., Gilitschenski, M. Riedmiller, D. Rus, and M. Wulfmeier, “Solving continuous control via q-learning,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.12566, 2022, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2210.12566.

- S. Fujimoto, H. Hoof, and D. Meger, “Addressing function approximation error in actor-critic methods,” In International conference on machine learning, pp. 1587-1596, 2018, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1802.09477.

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

| Atikah Surriani (Graduate Student, Member IEEE) received the B.Eng. degree in electrical engineering from the Universitas Lampung (Unila), Indonesia, in 2011, and the M.Eng. degree in electrical engineering from Universitas Gadjah Mada (UGM), Indonesia, in 2015. She is currently pursuing the Dr.Eng. degree in 2019 with the Universitas Gadjah Mada (UGM), and received Dr.Eng in 2024.. She is a Lecturer with Universitas Gadjah Mada (UGM), Indonesia. She was one of a Researcher with the Electrical Engineering UAV Research Centre (EURC), Universitas Gadjah Mada (UGM), from 2014 to 2015. Her research concern to control system and robotics especially, UAV control system and arm robot. |

|

|

| Hari Maghfiroh (Graduate Student Member, IEEE) obtained his bachelor's and master's degrees from the Department of Electrical and Information Engineering at Universitas Gadjah Mada (UGM), Indonesia, in 2013 and 2014, respectively. He also participated in a double degree master's program at the National Taiwan University of Science and Technology (NTUST) in 2014. Currently, he is a doctoral student in the Department of Electrical and Information Engineering at UGM and serves as a lecturer in the Department of Electrical Engineering at Universitas Sebelas Maret (UNS), Indonesia. His research interests include control systems, electric vehicles, and railway systems. He is the Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Fuzzy Systems and Control (JFSC) and is the recipient of the IEEE-VTS Student Scholarship Award for 2024. |

|

|

| Oyas Wahyunggoro (Member, IEEE) received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia, and his Ph.D. degree from Universiti Teknologi Petronas, Malaysia. He is currently a lecturer at the Department of Electrical and Information Engineering, Universitas Gadjah Mada. His research interests include evolutionary algorithms, fuzzy logic, neural networks, control systems, instrumentation, and battery management systems. |

|

|

| Adha Imam Cahyadi received a bachelor’s degree from the Department of Electrical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia, in 2002, a master’s degree in control engineering from KMITL, Thailand in 2005, and a D.Eng. degree from Tokai University, Japan, in 2008. He is currently a Lecturer with the Department of Electrical and Information Engineering, Universitas Gadjah Mada. His research interests include multi-agent control systems, control for systems with delays, and control for nonlinear dynamical systems and teleoperation systems. |

|

|

| Hanifah Rahmi Fajrin received her bachelor’s degree from Universitas Andalas, Department of Electrical Engineering in 2012 and Magister Degree from Universitas Gadjah Mada (Department of Electrical Engineering and Information Technology), Indonesia in 2015. Currently, she is pursuing her Ph.D degree in Soon Chun Hyang University, South Korea in Department of Software Convergence. She can be contacted by email: hanifah.fajrin@vokasi.umy.ac.id. |

Discount Factor Parametrization for Deep Reinforcement Learning for Inverted Pendulum Swing-up Control (Atikah Surriani)